Abstract

Background:

Traumatic diaphragmatic hernias are a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge due to variable presentations. Early repair is important because of risks of incarceration and strangulation of abdominal contents along with respiratory and cardiovascular compromise. Minimally invasive techniques have been useful for diagnosis and treatment of diaphragmatic hernias in both blunt and penetrating trauma.

Method:

We present the case of a 54-year-old victim of a motor vehicle crash who presented with a delayed diagnosis of a right-sided traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. By using a 4-port technique and intracorporeal suturing, the hernia was repaired. This case highlights the difficulties associated with diagnosing diaphragmatic hernias and the role of minimally invasive techniques to repair them.

Conclusion:

Minimally invasive surgical techniques are being increasingly used to both diagnose and repair traumatic diaphragmatic injuries with excellent results.

Keywords: Diaphragmatic hernia, Trauma, Minimally invasive repair, Blunt injury, Penetrating injury

INTRODUCTION

Trauma is the leading cause of acquired diaphragmatic hernias (DH). Correct diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernias is often missed in the acute setting.1–3 Patients are often asymptomatic or comatose, and imaging performed may not clearly depict the DH. Therefore, further studies may not be done, leading to incorrect diagnoses and treatments.4

Late-onset DH can present as a variety of clinical symptoms, such as cardiorespiratory or gastrointestinal complaints.1,3–6 Right-sided herniation may even be more difficult to detect than left-sided herniation. Thoracoscopy and laparoscopy are 2 of the approaches to minimally invasive repair of these defects.

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old woman was brought to the emergency department by EMS as a Level II trauma status after a motor vehicle crash. She was the driver of a vehicle that was T-boned by a deer on the passenger side of the car, and she subsequently lost control of the vehicle. The patient was wearing her seatbelt and the airbag deployed. She was unresponsive at the scene, and an attempt to intubate her in the field failed. She was ventilated with a bag-valve mask and later intubated in the emergency department. On arrival to the ER, she was hemodynamically stable with 100% saturation. Her Glasgow Coma Scale was 6T.

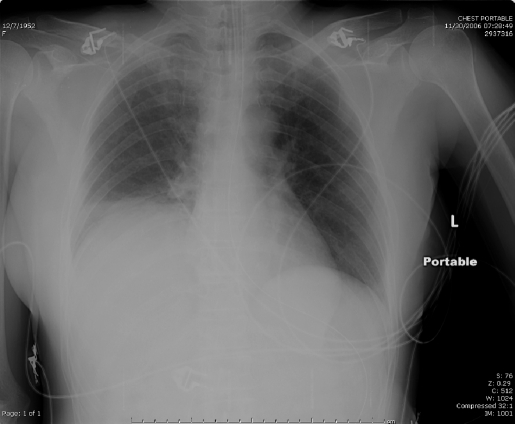

A plain chest film performed on arrival revealed elevation of the right hemidiaphragm with linear atelectasis at the right base (Figure 1). A computed tomographic (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen revealed right lower and middle lobe collapse and elevation of the right hemidiaphragm. There was left lung base atelectasis, and a Grade 3 liver laceration, but the great vessels were intact. The patient also had a closed head injury with subarachnoid hemorrhage, diffuse axonal injury, and a frontal scalp hematoma. Her other injuries included fractures of her right clavicle, multiple bilateral ribs, right wrist, stable pelvic fracture, sacrum, and unstable fracture of C2. The patient was admitted to the ICU, and her course was complicated by respiratory failure and pulmonary sepsis, which resolved with a tracheostomy and a prolonged course of antibiotics. The patient was transferred to the surgical floor 20 days later, and after another 5 weeks of hospitalization she was discharged to a long-term rehabilitation facility.

Figure 1.

Initial chest x-ray reveals elevation of the right hemidiaphragm with linear atelectasis at the right base.

Two days later, she was readmitted with shortness of breath, wheezing, and fever.

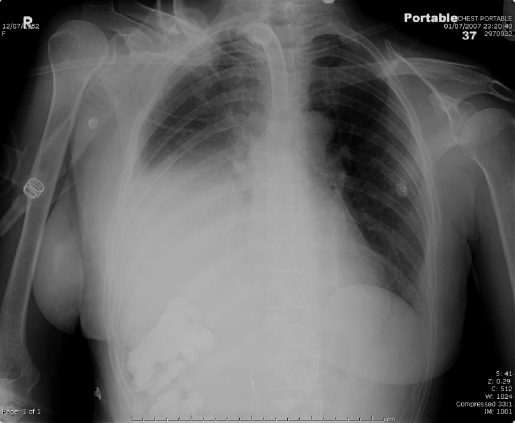

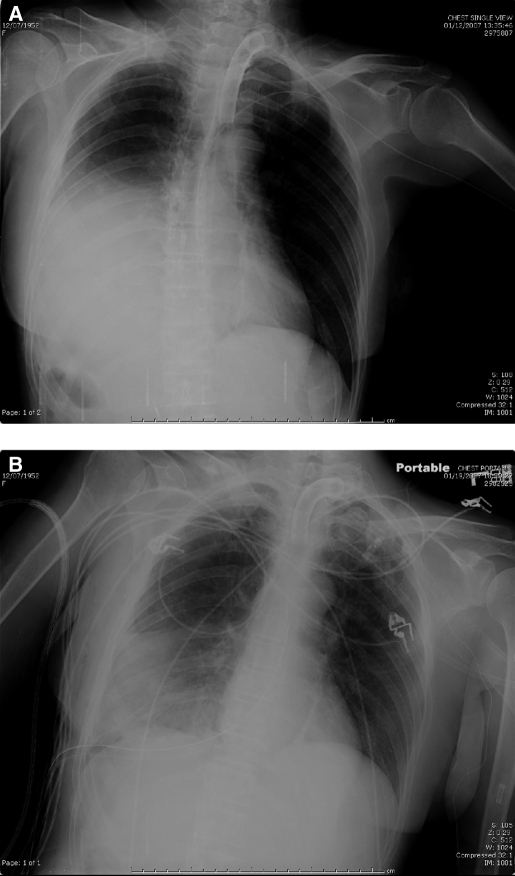

A chest x-ray showed a moderate-to-large right pleural effusion and opacity at the right lung base (Figure 2). A CT scan of the chest showed right diaphragmatic hernia with herniation of bowel alongside the liver, right lower lobe atelectasis, and mediastinal shift to the left (Figure 3). Bronchoscopy was performed and showed extrinsic compression and complete closure of the right lower lobe orifice and bronchi. The patient was given a course of antibiotics, and after resolution of her pneumonia, surgery was performed.

Figure 2.

Chest x-ray on readmission shows a moderate right pleural effusion with opacity at the right lung base.

Figure 3.

Computed tomographic scan of the chest and abdomen showing right diaphragmatic hernia with stable right pleural effusion, right lower lobe atelectasis, mediastinal shift to the left, and herniation of bowel alongside the liver into the thorax.

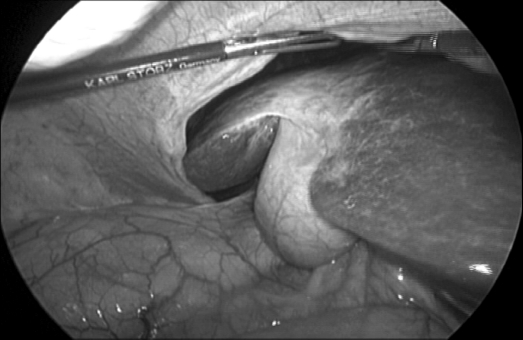

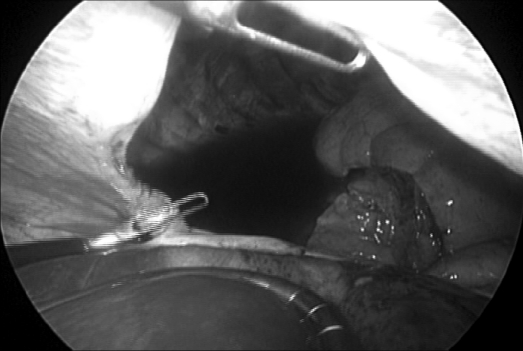

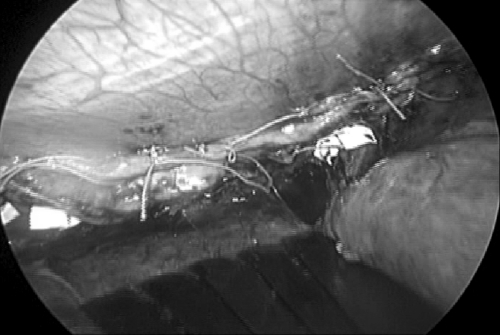

In the operating room, the patient was positioned with her right side elevated. Four trocars were used, 2 of which were 12mm. Laparoscopy revealed a large diaphragmatic defect with herniation of the right lobe of the liver into the thoracic cavity (Figure 4). The liver was pulled back into the abdomen revealing a collapsed right lower lobe, some pleural fluid, and the edges of a large diaphragmatic defect (Figure 5). Adhesions of the lower edge of the diaphragm were taken down, and the defect closed using interrupted figure-of-eight Surgidac sutures with PTFE pledgets (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Herniation of the right lobe of the liver though the defect in the right diaphragm.

Figure 5.

Retraction of the liver reveals a collapsed right lung, pleural fluid, and a large defect.

Figure 6.

Intraoperative photographs showing the closed defect.

A survey of the rest of the abdominal cavity was negative. A chest tube was inserted for drainage of the thorax, and the port sites were closed. The postoperative chest X-ray compared with the preoperative chest X-ray showed marked improvement in the borders of the right hemidiaphragm (Figure 7). The patient's postoperative course was complicated by a flare-up of respiratory infection, but she responded to antibiotics and was discharged to a long-term rehabilitation facility 2 weeks after the surgery.

Figure 7.

Preoperative (A) and postoperative (B) chest x-rays.

DISCUSSION

Diaphragmatic hernias (DH) can be categorized as occurring in the left or right diaphragm, being congenital or acquired, or having an early or late onset.

Congenital diaphragmatic hernias (CDH) are well described and occur in 1/2000 to 1/5000 live births, with 30% to 50% diagnosed in utero.7 Left-sided CDHs are more common than are right-sided and bilateral ones (85% vs. 8% to 21% vs 2%), with a 1:1.25 male to female ratio.7,8 Left-sided CDH may cause severe respiratory distress, gastrointestinal symptoms, or both, in the newborn, whereas right-sided CDH may cause fewer symptoms.

Trauma is the leading cause of acquired DH. Traumatic DHs are mostly left-sided (70% to 80%) vs. right-sided (15% to 24%) vs. bilateral (8%)1,10,11 Penetrating injury results in a 5% incidence of diaphragmatic injury, which is usually diagnosed and treated by laparotomy. Laparoscopy is a useful diagnostic tool in low-velocity penetrating injuries to assess violation of peritoneum and to survey the diaphragms. If not diagnosed promptly, even a small diaphragmatic injury may result in significant morbidity and require repair due to migration of organs aided by the combined “push-pull” mechanism of positive intraabdominal pressure and negative intrathoracic pressure. In blunt injury, which includes road accidents and falls, 15% of hospitalized patients have DH. The presentation of DH in blunt trauma can be divided into 2 distinct types. The first one is immediate herniation of abdominal contents through a large rent in the diaphragm produced by transient but very significant elevation of intraabdominal pressure. This is a dramatic presentation characterized by respiratory compromise and often by hemodynamic instability. The second, more insidious pattern is a diaphragmatic defect without immediate herniation of intraabdominal contents. This pattern is often initially overlooked in the acute setting1–3 and is only correctly diagnosed in 30% to 40% of cases.1,12 The current practice of nonoperative treatment of solid organ injuries decreases the number of laparotomies in the acute trauma setting, and imaging is notoriously inaccurate in the diagnosis of diaphragmatic injuries.

The time period before onset of symptoms can be variable,5,6 sometimes measuring in years.10 Delayed DH of-ten presents as cardiorespiratory or gastrointestinal complaints, such as dyspnea, coughing, chest pain, abdominal pain, or vomiting. Eventual diagnosis of DH is made on further investigation of these complaints. Late presentation of symptoms makes diagnosis even more difficult, and the misdiagnosis rate increases.4 When a diaphragmatic hernia presents symptomatically, a 20% to 66% morbidity rate exists due to gastrointestinal obstruction, perforation, incarceration, or respiratory compromise.2 Other less common causes of DH can be violent coughing, obesity, heavy lifting, multiparity, and iatrogenic causes like esophagogastric surgery.9

Our patient presented with fever, tachycardia, and respiratory symptoms during her second admission to the hospital, due to the diaphragmatic hernia with simultaneous pneumonia. The inability to communicate with our patient added to the delay in diagnosis and treatment of her DH.

Misinterpretation of radiological imaging can miss the diagnosis of DH. In cases of late-presenting CDH, Baglaj et al4 report that pneumothorax and pleural effusion were the most common initial findings. Eren et al1 reviewed imaging of the diaphragm after trauma and suggest that plain radiography as a first-line modality, followed by CT scans, which are feasible in the trauma setting. MRI would be very helpful in visualizing the defect and should be used in patients with a high suspicion of DH.

Plain chest film and CT scan of our patient on initial presentation after the motor vehicle crash, only revealed elevation of the right hemidiaphragm and right lower lung collapse (Figures 1, 2). This reading perhaps may have been the correct diagnosis at that time, with gradual herniation later on. Interestingly, MRIs focusing on her spinal injuries were ordered later during hospitalization.

In the literature regarding right-sided DH, mostly CDH is discussed. There is controversy about whether right-sided CDH has increased mortality or any influence in the morbidity of the neonate.8 The diagnosis of right-sided CDH is often delayed due to milder symptoms compared with symptoms accompanying left-sided CDH. Right-sided CDH can also be associated with a number of congenital defects and complications,8 and can present with other anomalies.7,13–15Therefore, it is important to recognize that such anomalies exist and perhaps can be present in longstanding right DH.

Our patient did not have any anomalies between the lung and liver. However, takedown of adhesions within the diaphragm itself was necessary to free the crura. If this DH had been left unrepaired, it is possible that adhesions between lung, liver, bowel, and diaphragm may have formed. Close proximity of the abdominal contents to the infected lung put our patient at risk for spread of infection.

The use of minimally invasive surgery for repair of DH is controversial. Thoracoscopic and laparoscopic approaches have been described.9,12,16–22 A recent review of the literature discussing CDH reports that mixed use of thoracoscopy and laparoscopy occurs.17 In fact, both techniques may be complimentary.23 Both thoracoscopic and laparoscopic approaches to repair DH have advantages over open surgery in that they result in minimal trauma, promote early recovery, and decrease hospital stay.

Thoracoscopy has been successful for repair of DH and may be easier due to good exposure in the thoracic cavity and has decreased the difficulty in reduction of herniated contents.17,22,24 Thoracoscopic repair of CDH in children and in select newborns could be the treatment of choice due to its safety and efficacy.17,22

Laparoscopy is a superior early diagnostic tool compared with thoracoscopy, because survey of the entire abdomen can be performed and subsequent repairs made, especially in the acute trauma setting.25,26 Laparoscopy provides better orientation and surgical exposure of both the abdominal and thoracic cavity (through the defect), permitting survey for other injuries,2,3,12 whereas in thoracoscopy, only one hemidiaphragm can be inspected at a time.20 Moreover, laparoscopy allows for the repositioning of herniated contents more easily in the abdominal cavity.12,16 Another advantage of laparoscopy is that the patient is not required to undergo single-lung ventilation as needed in thoracoscopy.27

A laparoscopic approach is best indicated in anteriorly or centrally located acute or chronic traumatic diaphragmatic hernia without concomitant severe abdominal or thoracic injury.12,16 Safety of laparoscopic repair of DH has been proven in many case reports but can be technically challenging.21 Therefore, surgical experience and meticulous technique are key to the success of laparoscopic repair. Use of a thoracoscopic or laparoscopic approach must be individualized for the patient's clinical condition, presence or absence of other injuries, type and duration of hernia, and the surgeon's experience with minimally invasive surgery.12,16

Given our patient's history of blunt trauma, a laparoscopic approach to diaphragmatic repair was preferred over thoracoscopy. Using laparoscopy, it was feasible to survey the rest of the abdomen, place the liver and bowel back into the abdominal cavity, and repair the diaphragmatic defect.

CONCLUSION

Diagnosis of traumatic diaphragmatic hernias can be difficult in the acute setting and can present later with variable symptoms and radiological findings. Diaphragmatic hernias should be considered early in the differential diagnosis of a trauma patient. Though right-sided diaphragmatic hernias are less common than left-sided ones, they occur more frequently than was once thought. Plain films, CT imaging, and MRI can help establish the diagnosis. Both thoracoscopy and laparoscopy are options to minimally invasive surgical approaches to repair, and the approach must be individualized by the clinical condition, presence of other injuries, type of hernia, and the skill level of the surgeon. Laparoscopy is a safe and successful approach to DH repair in the trauma patient, because further assessment and treatment of abdominal and thoracic injury can be facilitated.

Contributor Information

Maria R. Ver, Department of General Surgery, New York Medical College, Valhalla, New York, USA..

Aleksandr Rakhlin, Department of General Surgery, New York Medical College, Valhalla, New York, USA..

Francis Baccay, Department of General Surgery, New York Medical College, Valhalla, New York, USA..

Bindu Kaul, Department of General Surgery, New York Medical College, Valhalla, New York, USA..

Ashutosh Kaul, Department of Radiology, Albert Einstein Medical College, Bronx, New York, USA..

References:

- 1. Eren S, Kantarci M, Okur A. Imaging of diaphragmatic rupture after trauma. Clin Radiol. 2006;61(6):467–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaw LL, Jr., Potenza BM, Coimbra R, Hoyt DB. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198(4):668–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sirbu H, Busch T, Spillner J, Schachtrupp A, Autschbach R. Late bilateral diaphragmatic rupture: challenging diagnostic and surgical repair. Hernia. 2005;9(1):90–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baglaj M, Dorobisz U. Late-presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia in children: a literature review. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35(5):478–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Christie D, Chapman J, Wynne J, Ashley D. Delayed right-sided diaphragmatic hernia and chronic herniation of unusual abdominal contents. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(1):176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Launey Y, Geeraerts T, Martin L, Duranteau J. Delayed traumatic right diaphragmatic rupture. Anesth Analg. 2007;104(1):224–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tanaka S, Kubota M, Yagi M, et al. Treatment of a case with right-sided diaphragmatic hernia associated with an abnormal vessel communication between a herniated liver and the right lung. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(3):e25–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hedrick HL, Crombleholme TM, Flake AW, et al. Right congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Prenatal assessment and outcome. J Pediatr Surg. 39(3):319–323, 2004; discussion 319–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zerey M, Heniford BT, Sing RF. Laparoscopic repair of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Operative Techniques in General Surgery. 2006;8(1):27–33 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nursal TZ, Ugurlu M, Kologlu M, Hamaloglu E. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernias: a report of 26 cases. Hernia. 2001;5(1):25–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thillois J, Tremblay B, Cerceau F, et al. Traumatic rupture of the right diaphragm. Hernia. 1998;2:119–121 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huttl TP, Lang R, Meyer G. Long-term results after laparoscopic repair of traumatic diaphragmatic hernias. J Trauma. 2002;52(3):562–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robertson DJ, Harmon CM, Goldberg S. Right congenital diaphragmatic hernia associated with fusion of the liver and the lung. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(6):e9–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCabe AJ, Orr JD, Sharif K, De Ville de Goyet J. Right-sided diaphragmatic hernia in infants after liver transplantation. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(7):1181–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Strunk T, Simmer K, Kikiros C, Patole S. Late-onset right-sided diaphragmatic hernia in neonates - case report and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166(6):521–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Meyer G, Huttl TP, Hatz RA, Schildberg FW. Laparoscopic repair of traumatic diaphragmatic hernias. Surg Endosc. 2000; 14(11):1010–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Szavay PO, Drews K, Fuchs J. Thoracoscopic repair of a right-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005;15(5):305–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Whitson BA, Hoang CD, Boettcher AK, et al. Wedge gastroplasty and reinforced crural repair: important components of laparoscopic giant or recurrent hiatal hernia repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132(5):1196–1202, e1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mehta S, Boddy A, Rhodes M. Review of outcome after laparoscopic paraesophageal hiatal hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16(5):301–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wadhwa A, Surendra JB, Sharma A, et al. Laparoscopic repair of diaphragmatic hernias: experience of six cases. Asian J Surg. 2005;28(2):145–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matthews BD, Bui H, Harold KL, et al. Laparoscopic repair of traumatic diaphragmatic injuries. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(2):254–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nguyen TL, Le AD. Thoracoscopic repair for congenital diaphragmatic hernia: lessons from 45 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(10):1713–1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lomanto D, Poon PL, So JB, et al. Thoracolaparoscopic repair of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. Surg Endosc. 2001; 15(3):323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arca MJ, Barnhart DC, Lelli JL, Jr., et al. Early experience with minimally invasive repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernias: results and lessons learned. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(11):1563–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cueto J, Vazquez-Frias JA, Nevarez R, Poggi L, Zundel N. Laparoscopic repair of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2001;11(3):209–212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smith CH, Novick TL, Jacobs DG, Thomason MH. Laparoscopic repair of a ruptured diaphragm secondary to blunt trauma. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(5):501–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Frantzides CT, Madan AK, O'Leary PJ, Losurdo J. Laparoscopic repair of a recurrent chronic traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Am Surg. 2003;69(2):160–162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]