Abstract

Introduction:

A wandering spleen occurs when there is a laxity of the ligaments that fix the spleen in its normal anatomical position.

Case Report:

We present the case of a wandering spleen in a 20-year-old female who presented with recurrent pancreatitis and underwent a laparoscopic splenectomy.

Discussion:

The presentation of a wandering spleen varies from an asymptomatic mass to splenic infarct with an acute abdomen. Its correct diagnosis relies mostly on imaging studies. Treatment consists of performing either splenectomy or splenopexy.

Conclusion:

The diagnosis of wandering spleen can often be difficult due to the intermittent nature of the torsion. Computed tomography studies for diagnosis and laparoscopic surgery have changed the management of this interesting disease.

Keywords: Wandering spleen, Splenic volvulus, Splenic torsion, Laparoscopic splenectomy

INTRODUCTION

Wandering spleen (WS) is a rare condition that occurs when the spleen lacks its usual peritoneal attachments, and thus assumes abnormal mobility. There is an incomplete fixation of the gastrosplenic and splenorenal ligaments.1 Occasionally, the spleen is only attached at the hilum by a long vascular pedicle that allows it to shift to extraanatomical positions. Clinical presentation varies from that of an asymptomatic mass, recurrent abdominal pain, intestinal obstruction, or even an acute abdomen. With torsion of its vascular pedicle, there may be fevers, chills, and peritoneal signs.2,3 Diagnosis is largely dependent on imaging studies with computed tomography being the preferred modality. Ultrasound has been used to aid in the diagnosis, and it was found that a low position of the spleen was the most specific sonographic finding although excessive gas may obscure findings.4 The treatment is either splenopexy or splenectomy, depending largely on the patient's age, vascular status, and size of the spleen. In this age of minimally invasive surgery, the laparoscopic approach is preferred.

We report the case of a 20-year-old female with recurrent abdominal pain who underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy for presumed gallstone pancreatitis. Her symptoms resolved only to recur shortly. Subsequent computed tomography revealed a wandering spleen with obstruction of the pancreatic duct.

CASE REPORT

The patient was a 20-year-old female with recurrent midepigastric abdominal pain that radiated to the right upper quadrant and back. She described a 2-year history of similar episodes that spontaneously resolved without medical treatment.

During her first episode, she was 7-months pregnant and was diagnosed with pancreatitis. She denied any alcohol or drug use and was only taking multivitamins. Amylase and lipase, which were mildly elevated, returned to normal values within 24 hours. An abdominal ultrasound revealed no abnormalities, although the spleen was not visualized due to excessive bowel gas. The patient was discharged home and told to follow up with a gastroenterologist for further evaluation after her delivery. She did not return.

One year after her initial episode, she presented to our emergency department complaining of persistent, severe midepigastric abdominal pain associated with nausea and vomiting. On admission, her white blood cell count was 15.6x109/L, hemoglobin and hematocrit were 14.3g/L and 41.2%, and her platelet count was 249x109/L. Electrolytes were all within normal ranges. The amylase level was 1.220U/L, and lipase level was 1364U/L. Lactic dehydrogenase level was 235U/L (normal range, 94 to 250). The total bilirubin was 0.7mg/dL, and no liver enzyme abnormalities were present. An abdominal ultrasound revealed a small shadowing gallstone in the lumen of the gallbladder without evidence of ductal dilatation or wall thickening (Figure 1). Minimal fluid was in the upper abdomen. The diagnosis was felt to be biliary pancreatitis. The pancreatitis resolved within 3 days, and the patient underwent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiography. Surgery was uneventful, and the cholangiogram did not show any biliary obstruction. The spleen was noted to be in its normal anatomical position. The patient was discharged home on the first postoperative day, tolerating a regular diet and without complaints.

Figure 1.

Abdominal ultrasound shows a small shadowing gallstone in the lumen of the gallbladder without evidence of ductal dilatation or wall thickening

One year after surgery, she presented again with the acute onset of midepigastric pain radiating to the back, associated with nausea and vomiting. The white blood cell count was 9.0x109/L, hemoglobin and hematocrit were 14.2g/L and 40.5%, and the platelet count was 238x109/L. The amylase and lipase levels were 1134U/L and 2790U/L, respectively. Physical examination revealed a painful, palpable abdominal mass located in the right upper quadrant. There was no associated fever (37.3°C), and the patient remained hemodynamically stable. An abdominal contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) was diagnostic for a wandering spleen. The spleen was located in the right upper quadrant, adjacent to the liver and gallbladder fossa. There was significant displacement of the pancreatic tail into the splenic hilum (Figure 2). Abdominal ascites, as well as a very large air-filled transverse colon were also seen.

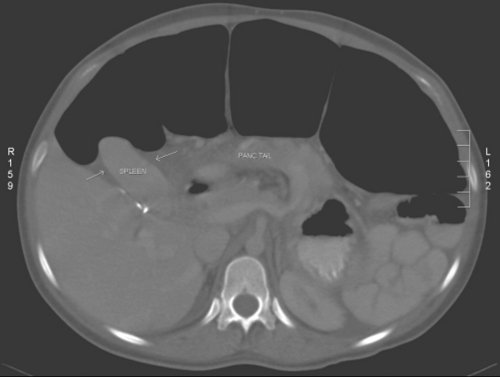

Figure 2.

Computed tomographic scan shows the spleen in the right upper quadrant, adjacent to the liver. There is significant displacement of the pancreatic tail into the splenic hilum, as well as a very large air-filled transverse colon.

The pancreatitis resolved and elective splenectomy was scheduled. A follow-up CT scan done for abdominal pain 3 weeks later showed the spleen in a normal anatomical position (Figure 3). Preoperative Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae vaccines were administered. Two weeks later, the patient underwent a laparoscopic splenectomy. The spleen was found to be enlarged and located in the right upper quadrant. No peritoneal or colic attachments were present, and the short gastric vessels were long, enlarged, and tortuous. The displacement of the spleen was causing an organo-axial torsion of the stomach (Figure 4). The tail of the pancreas was folded onto the body. With simple retraction, all organs were returned to their normal position. The short gastric vessels were transected with a Harmonic scalpel, and the splenic hilum was transected with an endovascular cutting stapler. The specimen was placed in a bag and morselized. Pathology reported microscopically normal splenic tissue without any evidence of malignancy or infiltrative disease. The patient had an uneventful recovery, and on her 3-month follow-up she remained asymptomatic.

Figure 3.

A follow-up computed tomographic scan shows the spleen in normal anatomical position with persistence of the transverse colon dilatation.

Figure 4.

Initial laparoscopic view shows the spleen in the right upper quadrant underneath the liver. The displacement of the spleen is causing an organo-axial torsion of the stomach.

DISCUSSION

The spleen begins its development from a mass of mesenchymal cells in the dorsal mesogastrium in the fifth week of gestation. A counterclockwise rotation of the foregut and elongation of the mesogastrium allow it to assume its normal anatomical position in the left upper quadrant. During this migration, the spleen establishes its peritoneal connections with the left kidney and stomach, the splenorenal and gastrosplenic ligaments.5 When these ligaments are congenitally absent or abnormally elongated, the spleen acquires wanderlust. This condition has been described as wandering spleen, floating spleen, or splenic ptosis.6,7

Johannes van Horne in 1667 gave the first description of a wandering spleen as an incidental finding during an autopsy. The real incidence of wandering spleen is unknown, because up to 50% remain asymptomatic.8 In a review of several large series of splenectomies for disease, the incidence was <0.2%.9,10

The cause is not precisely known, yet evidence points towards 2 main causes. The most common cause appears to be a failure of fusion of the dorsal mesogastrium during the fifth and sixth week of development resulting in an unusually long splenic pedicle.11 Wandering spleen has also been seen in disorders where there is failure of foregut rotation and fusion of the dorsal mesogastrium, such as prune-belly syndrome.12,13 The increased association of wandering spleen during pregnancy and in the multiparous female has led some to suggest that hormonal influences affect the laxity of the splenic ligaments.14 Contributory factors are enlargement of the spleen, visceroptosis, and poor abdominal tone commonly seen in multipara.15

Clinical presentation varies from that of an asymptomatic mass, recurrent abdominal pain, intestinal obstruction, or even an acute abdomen. With torsion of its vascular pedicle, there may be fevers, chills, and peritoneal signs.1–3 When compromise of the vascular supply is present, necrosis of the spleen as well as the tail of the pancreas may occur.14 Several case reports exist of wandering spleen presenting as a bleeding diathesis due to hypersplenism and thrombocytopenia with complete reversal of hematological symptoms after surgical management.16,17 Recurrent pancreatitis as seen in this patient is an unusual finding.

The variability as well as intermittent nature of symptoms makes wandering spleen an elusive diagnosis in which the clinician's awareness and high index of suspicion remain key to its correct identification. The diagnosis is best made with computed tomography, but if unavailable, low positioning of the spleen on ultrasound is helpful.1,4 Conventional radiographs of the abdomen may show distended bowel loops and may suggest a mass-occupying lesion. If torsion has occurred, Doppler studies will demonstrate absence of blood flow to the spleen.

For many years, the preferred treatment was surgical removal of the spleen, initially by conventional laparotomy and more recently by laparoscopy. Due to the spleen's important role in the reticuloendothelial system and the risk of postsplenectomy sepsis, there has been renewed interest in the role of splenopexy. Splenic preservation is especially recommended in extremely young patients who are at particular risk for postsplenectomy sepsis.18 This can be performed by forming a retroperitoneal pouch in which the spleen is placed, or by inserting a Prolene or Vycril bag that is fashioned around it and secured in the left upper quadrant.11,19

CONCLUSION

This report describes a young female with a wandering spleen who presented with recurrent pancreatitis. The diagnosis of wandering spleen can often be difficult due to the intermittent nature of the torsion. Computed tomography studies for diagnosis and laparoscopic surgery have changed the management of this interesting disease. We recommended splenectomy secondary to repeat bouts of pancreatitis and the enlarged size of the spleen in an otherwise healthy adult.

References:

- 1.Dahiya N, Karthikeyan D, Vijay S, Kumar T, Vaid M. Wandering spleen: unusual presentation and course of events. Ind J Radiol Imag 2002;12:3:359–362 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosin D, Bank I, Rimon U, et al. Laparoscopic splenectomy for torsion of wandering spleen associated with celiac axis occlusion. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(7):1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin CH, Wu SF, Lin WC, Chen AC. Wandering spleen with torsion and gastric volvulus. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;104(10):755–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karmazyn B, Seinberg R, Gayer G, Grozovski S, Freud E, Kornreich L. Wandering spleen: the challenge of ultrasound diagnosis: report of 7 cases. J Clin Ultrasound. 2005;33(9):433–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore KL, Persaud TVN. The digestive system. In: Moore KL, Persaud TVN, eds. The Developing Human, Clinically Oriented Embryology. 6th ed Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1998;271–302 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abell I. Wandering spleen with torsion of the pedicle. Ann Surg. 1933;98(4):722–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lott HS. Case of floating spleen with twisted pedicle, celiotomy, splenectomy, recovery. Am J Obstet. 1912;66:985–986 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padilla D, Ramia JM, Martin J, Pardo R, Cubo T, Hernandez-Calvo J. Acute abdomen due to spontaneous torsion of an accessory spleen. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:429–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whipple HO. The medical-surgical splenopathies. Bull NY Acad Med. 1939;15:174–176 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayo WJ. A review of 500 splenectomies with special reference to mortality and end results. Ann Surg. 1928;88(3):409–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane TM, South LM. Management of a wandering spleen. J R Soc Med. 1999;92:84–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aligbad H, Foker J. Splenic torsion and the prune-belly syndrome. Paediatr Surg Int. 1987;2:369–371 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teramoto R, Opas LM, Andrassy R. Splenic torsion with prune belly syndrome. J Pediatr. 1981;98(1):91–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilman RS, Thomas RL. Wandering spleen presenting as acute pancreatitis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 101(5 pt 2):1100–1102, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koppikar MG, Vaze AM, Bapat RD. Wandering spleen. J Postgrad Med. 1981;27:42–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benoist S, Imbaud P, Veyrieres M. Reversible hypersplenism after splenopexy for wandering spleen. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45(24):2430–2431 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moll S, Igelhart JD, Ortel TL. Thrombocytopenia in association with a wandering spleen. Am J Hematol. 1996;53(4):259–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buehner M, Baker MS. The wandering spleen. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;175(4):373–387 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavazos S, Ratzer ER, Fenoglio ME. Laparoscopic management of the wandering spleen. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2004;14(4):227–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]