Abstract

Spillage of gallstones may occur in the course of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The incidence of this mishap and its consequences are variable. Ignored by many surgeons, stone spillage may be the source of significant morbidity many years after surgery. In this report, we describe the clinical course of a patient who presented with upper abdominal pain and swelling. The past history was positive for laparoscopic cholecystectomy 15 years earlier. After excision, the swelling was found to be a pseudocyst formed around spilled gallstones during a previous cholecystectomy. Apart from postoperative wound infection, the patient recovered well and remains so. Here, we discuss the problem and provide suggestions for spillage prevention and stone retrieval once spillage occurs.

Keywords: Gallstones, Spillage, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

INTRODUCTION

Since its introduction in the 1980s,1 laparoscopic cholecystectomy has made vast strides, supplanting open cholecystectomy as the gold standard for gallbladder disease. The great enthusiasm for laparoscopic cholecystectomy is undoubtedly well founded. This is based on the patient's greater comfort in terms of less postoperative pain, speedier recovery, shorter hospital stay, and earlier return to work.

Unfortunately, these advantages are gained at the expense of an increased incidence of biliary injury.2 Moreover, a unique problem that was almost unknown in the era of open surgery emerged, namely the problem of spilled gallstones. The limited ability of the surgeon to retrieve spilled stones laparoscopically3 leads many surgeons to leave them behind if efforts at retrieval are not straightforward. Although this is inconsequential in the majority of cases,4,5 a certain group of patients are at increased risk for developing complications.6 Moreover, the presence of infected bile7 and stone composition may be a determining factor.8 In these situations, spilled stones should not be simply ignored.

CASE REPORT

A 45-year-old female presented with insidious central colicky abdominal pain and swelling of 6-months duration. The past history was remarkable for hypertension and laparoscopic cholecystectomy 15 years earlier followed by a caesarean delivery 2 years later.

Examination showed a fairly healthy, obese patient with normal vital signs. Her pulse rate was 84/minute, blood pressure was 128/80 mm Hg, and temperature was 37°C. Abdominal examination showed laparoscopic port scars and a smooth, nontender, well-defined, 6x6-cm lump in the epigastric and periumbilical regions with no organomegaly.

Investigations showed hemoglobin of 11.7 g/dL, white cell count 7.100/mm3, platelet count 391.000/mm3. Her blood urea, creatinine, and electrolytes were normal, and the hydatid serology test was negative. Computerized axial tomography (CT) scan showed a 10x8x6-cm encapsulated cystic mass in the upper abdomen, attached to the rectus abdominis muscle and displacing the peritoneum and intestinal loops (Figure 1). No calcification was seen on CT scan, although abdominal ultrasound showed focal calcification in the dependent part of the cyst.

Figure 1.

Computed tomographic scan of the abdomen showing a cystic mass attached to the undersurface of the rectus abdominis, displacing the intestinal loops and peritoneum.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a hiatus hernia and erosive gastritis with evidence of extrinsic compression on the stomach. Endoscopic biopsy concluded the procedure, and it later showed superficial gastritis, for which a proton pump inhibitor was started and continued for 6 weeks. Among others, 2 diagnoses were primarily considered: reaction to gallstones spilled during the previous cholecystectomy or a hydatid cyst with negative serology.

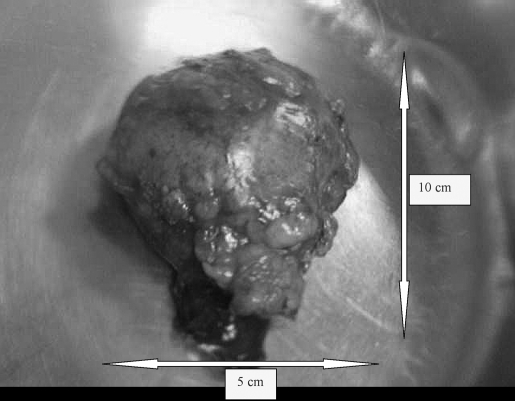

At surgery, precautions against hydatid fluid spillage were taken. The abdomen was entered through an upper midline incision, and a 10x5-cm cystic mass attached to the posterior rectus sheath and extending from the umbilicus to the epigastric port scar was found (Figures 2 and 3). Aspiration returned 120 mL of turbid yellowish fluid, and the cavity was refilled with hypertonic saline. With careful dissection, the intact mass was completely excised, and the abdomen was closed. On opening the cyst, multiple faceted stones were found inside (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

The mass seen during surgery.

Figure 3.

The mass after excision.

Figure 4.

Magnified view of gallstones discovered after opening the cyst. The largest was <1 cm in its greatest dimension.

Postoperatively, the patient convalesced well enough to be discharged on the fifth postoperative day. Two weeks later, she was readmitted with purulent discharge from the lower end of the wound, which was opened and debrided. The infection cleared rapidly aided by a short course of antibiotics, and the wound gap was resutured after 2 days.

Culture of the cyst fluid grew Enterobacter aerogenes, and microscopic examination revealed a fibrous wall with abundant cholesterol clefts (Figure 5) with infiltration by the chronic inflammatory cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histocytes. Foreign body multinucleated giant cells were also seen engulfing and surrounding cholesterol clefts (Figure 6). The cyst was lined by granulation tissue and lacked an epithelial lining.

Figure 5.

Photomicrograph showing multiple cholesterol clefts (white spaces) within the fibrous wall of a cyst with chronic inflammatory cells (X 100, H & E)

Figure 6.

Photomicrograph showing chronic inflammatory cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, histocytes, and cholesterol clefts surrounded and engulfed by multinucleated foreign body giant cells (arrows) forming foreign body granulomatous reaction (X 400, H&E).

In her first outpatient visit, 2 weeks later, the patient remained in good condition, and her wound had well healed.

DISCUSSION

Gallbladder perforation may occur in the course of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Bile leak invariably accompanies minor perforations, and depending on their size, stone spillage may also follow.

The incidence of gallbladder perforation varies from 10% to 40%,4,5,9–12 and the incidence of stone spillage is 5.7%.4 However, complications of spillage are rare.4,5 In a report on 10,174 patients, stones spilled in 581 patients (5.7%) and were retrieved in only 34 patients. In the remaining 547 patients, only 8 patients (0.08%) developed complications.4

The problem of spilled stones has been uniquely bound to laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In their literature review, Papasavas et al3 found only 2 cases of stone spillage in open cholecystectomy, but they found the same complication in 127 cases of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This is undoubtedly related to the difficulty with which spilled stones could be retrieved by laparoscopic compared with open means.3

Due to the low incidence of complications, conversion to open surgery is seldom considered.4,5 Similarly, incidental discovery of spilled stones in the absence of complications is not an indication for laparotomy, because the majority of cases remain asymptomatic.13

Why complications occur in a minority of patients while sparing the majority has been the basis of research, and risk factors have been identified. Older age, male sex, acute cholecystitis, pigment stones, number of stones (>15), size of the stone (>1.5 cm), perihepatic localization of lost stones7,14 have all been linked to increased complication rates. Additionally, experimental studies have shown that the presence of infected bile increases the incidence of infective complications.7 In these situations, if complete stone retrieval by laparoscopic means is not successful, conversion to open cholecystectomy should be considered.

Gallbladder perforation may occur at any of the principal steps of the procedure, namely grasping and traction of the gallbladder, its dissection from its bed, and finally its extraction.15 Risk factors associated with perforation have also been identified: acute cholecystitis, the presence of adhesions, obese patients, advanced age, male sex, and the surgeon's experience.10

Because acute cholecystitis is associated with an increased complication rate due to stone spillage14 and the gallbladder has a greater tendency to perforate,10 it might be wiser to refrain from operating in the acute setting, in patients with increased risk for developing complications.

Atraumatic graspers applied to the gallbladder wall are a main cause for gallbladder perforation. Because gallbladder traction is indispensable during cholecystectomy, another safe grasping means should be utilized in patients at increased risk of perforation. A suction grasper device that utilizes suction to keep its hold on the gallbladder wall without crushing may be the answer. Such a device has been effective in laparoscopic splenectomy.16 Because a specially designed gallbladder suction grasper is not currently available, instrument makers are invited to contemplate the idea. Equally important is the identification of and adherence to the correct planes during gallbladder dissection to avoid inadvertent entry into the gallbladder lumen.

For stone retrieval, ordinary graspers are the most commonly used means. Other innovative techniques include pressure ejection whereby the cannula is moved over the stone and the port valve is rapidly opened to allow the high intraperitoneal pressure to eject the stone. Also, suction connected to a 10-mm port that is then applied directly over the stone may be helpful. Alternatively, suction tubing may be passed down the port and positioned over the stone.17

Abscesses may form around spilled stone, and the commonest site is the extraction port.6 During gallbladder extraction, the organ is usually squeezed through the narrow wound and the intraluminal pressure may mount significantly. If this exceeds certain limits, the gallbladder may burst or tear, evacuating its load into the peritoneal cavity or the parietis. This may be facilitated by injury to the gallbladder wall during dissection. Stones thus left behind may lead to abscess formation years after surgery.18

Commercial gallbladder retrieval devices are currently available. These devices though not particularly expensive will certainly add to the cost of an already expensive procedure, and this led many surgeons to dispense with them. This practice, though self-explanatory, is not without risks. Using a retrieval device prevents bile contamination at the extraction site. Equally important, bursting or tearing of the gallbladder, if it occurs, remains contained within the device, thus avoiding the sequels of free rupture. Different retrieval devices have been produced from handy inexpensive materials. The utilization of a surgical glove properly trimmed to suit the purpose18,19 is a practical example. In this respect, limited extension of the extraction wound aided by evacuation of the gallbladder of its contents while still inside the abdomen, will also ease extraction and avoid rupture.

In the case presented here, stones were implanted in the abdominal wall during gallbladder extraction. They remained dormant for years while inciting a slow granulomatous foreign body reaction to present later with a pseudocyst. It is probable that the sterility of bile prevented earlier abscess formation and that a blood-born infection occurred later.

In many cases, the condition creates a diagnostic dilemma, particularly if stone spillage is not documented, while in others, the diagnosis is facilitated by the documentation of stone loss at a previous cholecystectomy. For that reason, the intraoperative event of stone spillage should be clearly documented in the patient's file to avoid any future diagnostic dilemma. In the present case, we considered the diagnosis based on the history of cholecystectomy and ultrasound findings, and as hydatid disease is endemic in our area, the possibility of echinococcal infection was also taken into account.

Complications usually take 4 months to 5 months on the average to present.6 Rarely, much longer durations have been reported.20 In our case, the duration represents the second longest in the literature, next only to that reported by Rothlin.20 Of added interest is the presentation as an infected pseudocyst, which has never been previously reported.

CONCLUSION

Precautions against gallbladder rupture and stone spillage during laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be taken. While currently not an indication for conversion, every effort should be made to retrieve spilled stones. Lost stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be clearly documented. The wisdom to avoid conversion in patients at risk of developing complications should be questioned.

Contributor Information

Abdul Rahman Arishi, Department of Surgery, King Fahad Central Hospital, Jazan, Saudi Arabia..

M. Ezzedien Rabie, Departments of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Jazan University and King Fahad Central Hospital, Jazan, Saudi Arabia..

M. Shahid Hussain Khan, Department of Surgery, King Fahad Central Hospital, Jazan, Saudi Arabia..

Hassan Sumaili, Department of Surgery, King Fahad Central Hospital, Jazan, Saudi Arabia..

Hassan Shaabi, Department of Surgery, King Fahad Central Hospital, Jazan, Saudi Arabia..

Nabil Tadros Michael, Department of Histopathology, King Fahad Central Hospital, Jazan, Saudi Arabia..

Bheem Sing Shekhawat, Department of Histopathology, King Fahad Central Hospital, Jazan, Saudi Arabia..

References:

- 1.Dubois F, Icard P, Berthelot G, Levard H. Coelioscopic cholecystectomy: preliminary report of 36 cases. Ann Surg. 1990;21(1):60–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vecchio R, MacFadyen BV, Latteri S. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an analysis on 114,005 cases of United States series. Int Surg. 1998;83:215–219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papasavas PK, Caushaj PF, Gagné DJ. Spilled gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2002;12(5):383–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schafer M, Suter C, Klaiber C, Wehrli H, Frei E, Krähenbühl L. Spilled gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A relevant problem? A retrospective analysis of 10,174 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:291–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Memon MA, Deeik RK, Maffi TR, Fitzgibbons RJ., Jr The outcome of unretrieved gallstones in the peritoneal cavity during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A prospective analysis. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:848–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brueggemeyer MT, Saba AK, Thibodeaux LC. Abscess formation following spilled gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. 1997;1:145–152 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zorluoglu A, Ozguc H, Yilmazlar T, Güney N. Is it necessary to retrieve dropped gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Surg Endosc. 1997;11:64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart L, Smith AL, Pellegrini CA, Motson RW, Way LW. Pigment gallstones form as a composite of bacterial microcolonies and pigment solids. Ann Surg. 1987;206(3):242–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice DC, Memon MA, Jamison RL, et al. Long-term consequences of intraoperative spillage of bile and gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarli L, Pietra N, Costi R, Grattarola M. Gallbladder perforation during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 1999;23:1186–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura T, Goto H, Takeuchi Y, et al. Intraabdominal contamination after gallbladder perforation during laparoscopic cholecystectomy and its complications. Surg Endosc. 1996;10(9):888–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diez J, Arozamena C, Gutierez L, Bracco J, Mon A, Sanchez Almeyra R, Secchi M. Lost stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. HPB Surg. 1998;11:105–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torello Viera F, Armellini E, Rosa L, et al. Abdominal spilled stones: ultrasound findings. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31(5):564–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brockmann JG, Kocher T, Senninger NJ, Schürmann GM. Complications due to gallstones lost during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(8):1226–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aytaç B, Cakar S. The outcome of gallbladder perforation during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Chir Belg. 2003;103(4):388–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gentilli S, Velardocchia M, Ferrero A, Martelli S, Donadio F. Laparoscopic splenectomy. How to make it easier using an innovative atraumatic suction grasper. Surg Endosc. 1998;12(11):1345–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daurka J, Loh A, Bird R, Howard A. A new laparoscopic technique: suction removal of spilled gallstones. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:677–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao CC, Wong HH, Yang CC, Lin C. Abdominal wall abscess secondary to spilled gallstones: late complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and preventive measure. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Techn A. 2001;11(1):47–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yano H, Okada K, Kinuta M, Iwazawa T, Kanoh T, Monden T. Use of non-powder surgical glove for extraction of gallbladder in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Digest Endosc. 2003;15:315–319 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothlin MA, Schob O, Schlumpf R, Largiadèr F. Stones spilled during cholecystectomy: a long-term liability for the patient. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1997;7:432–434 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]