Abstract

With the expanding indications for minimally invasive surgery, the management of small bowel obstruction is evolving. The laparoscope shortens hospital stay, hastens recovery, and reduces morbidity, such as wound infection and incisional hernia associated with open surgery. However, many surgeons are reluctant to attempt laparoscopy in patients with significantly distended small bowel and a history of multiple previous abdominal operations. We present the management of a patient with a virgin abdomen who presented with a small bowel obstruction most likely secondary to Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome who was successfully managed with laparoscopic lysis of adhesions.

Keywords: Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome, Chilaiditi syndrome, Small bowel obstruction

INTRODUCTION

Adhesive small bowel obstruction (SBO) is a common and frequently encountered problem. If initial conservative management fails, operative exploration, and lysis of adhesions is required. In patients with multiple previous surgeries and significantly dilated small bowel, surgical access to the peritoneal cavity can be quite difficult and is associated with significant complications. Traditional dictum would state that laparoscopy is contraindicated in such patients.

However, we are seeing an increased incidence of SBO in patients whose only previous abdominal surgery was via the laparoscope. In these patients, and in those with virgin abdomens, the laparoscopic approach may be the preferred way to diagnose and treat SBO. The following case presentation is of a patient with no previous abdominal surgery who presented with signs and symptoms of SBO. The patient was diagnosed and successfully treated using laparoscopy. We propose that laparoscopy is a viable option for diagnosis and treatment of patients with SBO and no history of abdominal surgery.

CASE REPORT

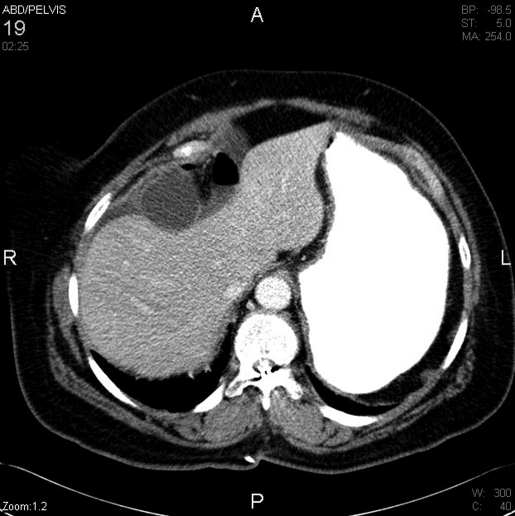

A 64-year-old female presented with 24 hours of nausea, abdominal pain, and vomiting. She denied any prior abdominal surgery or trauma. Her past medical history was significant only for hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and high cholesterol. An abdominal x-ray revealed multiple loops of dilated small bowel with air fluid levels consistent with a small bowel obstruction. Subsequent computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed multiple dilated loops of small bowel consistent with SBO, but no obvious underlying cause (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included internal hernia, neoplasm, spontaneous adhesion, stricture, or congenital abnormality.

Figure 1.

Small bowel obstruction with an apparent suprahepatic transition zone.

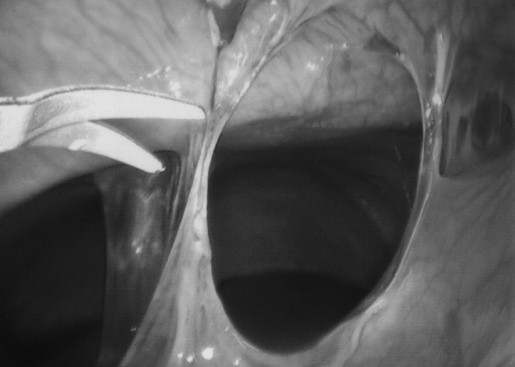

The patient was treated conservatively overnight with bowel rest and nasogastric tube decompression. Her symptoms did not improve with conservative treatment, and she was taken to the operating room for a diagnostic laparoscopy. The peritoneal cavity was easily accessed using an infraumbilical Hassan technique and pneumoperitoneum was established to 15 mm Hg. After the camera was inserted, a loop of jejunum was found incarcerated by adhesive bands in the right upper quadrant (Figure 2). The intraoperative diagnosis was an adhesive SBO secondary to Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome. The adhesions were easily taken down with endoscopic scissors, and the small bowel obstruction was released (Figure 3). The incarcerated portion of bowel was viable, and the remaining small bowel was examined. No other area of obstruction was found. Postoperatively, the patient did well and was discharged home on hospital day 4.

Figure 2.

Loop of jejunum incarcerated in adhesive bands between the liver and anterior abdominal wall.

Figure 3.

Laparoscopic lysis of adhesion with Endoshears.

DISCUSSION

Small bowel obstruction is the most commonly encountered surgical disorder of the small bowel.1 Frequently encountered causes of small bowel obstruction include adhesions (67% to 93%), hernia (11% to 20%), neoplasm, inflammatory bowel disease, foreign body, volvulus (3%), intussusception (4%), and congenital abnormalities.1 The diagnosis of small bowel obstruction requires an accurate history and physical. The initial radiographic study frequently is an abdominal series. Computed tomography has become the definitive radiographic study, as the scan will demonstrate the point of obstruction in addition to any other underlying pathology. Enteroclysis or a small bowel follow through is occasionally used to evaluate the small bowel mucosa or, less frequently, for therapeutic value. Initial treatment of SBO without associated fever, elevated white blood cell count, or abdominal pain is conservative. Definitive treatment of a small bowel obstruction is directed towards the cause. Surgical intervention traditionally consisted of a laparotomy, although more surgeons are opting for a minimally invasive approach.1

Few surgeons eagerly anticipate the fourth “lap and lysis” for recurrent SBO. Entry into the peritoneal cavity, small bowel enterotomy, ventral hernia, and enterocutaneous fistulae are all very real issues, and the postoperative course is rarely smooth. Despite hyaluronate-based bioresorbable membranes, the fifth exploration seems to be inevitable. Aggressive minimally invasive surgeons are attempting laparoscopy in these patients, with entry in the left upper quadrant where adhesions are frequently less dense. However, conversion rates remain high (43%).

With the increasing numbers of advanced laparoscopic surgeries, especially bariatric procedures, a significant number of patients are presenting with SBOs without prior laparotomy. These patients, along with those who have had no previous surgery, are ideal candidates for the laparoscopic approach. The peritoneal cavity can be entered with minimal risk, the diagnosis made, and not infrequently the underlying pathology can be addressed with advanced laparoscopic skills. Patients benefit not only from the reduced hospital stay, accelerated return of bowel function, early recovery, and fewer wound infections, but they also form fewer adhesions postoperatively. Recent literature supports the reduced incidence of subsequent SBO following laparoscopy versus open surgery for the same procedure.2

Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome is a localized fibrinous inflammation affecting the anterior surface of the liver and adjacent peritoneum in conjunction with acute salpingitis. It occurs in 1% to 10% of patients with pelvic inflammatory disease.3,4 Although historically associated with gonococcus, Chlamydia trachomatis is the most frequent infectious agent.3 As part of the inflammatory response, fibrous adhesive bands may form between the liver and the diaphragm or anterior abdominal wall. Patients with this syndrome typically present with right upper quadrant pain that mimics cholecystitis.3 The diagnosis is typically made incidentally during laparoscopy or laparotomy. Antibiotics should be administered during the acute infection. In the chronic phase, if the patient is symptomatic, lysis of adhesions is required.5 Our patient did not recall a prior infection, as is frequently the case, but we are reasonably certain this was the cause of her right upper quadrant adhesions.

Chilaiditi syndrome, the interposition of bowel between the liver and diaphragm, is likewise an unusual cause of obstruction due to right upper quadrant pathology. This roentographic finding typically is incidental, occurs in males, and has an incidence of 0.025% to 0.28%.6 A redundant transverse colon on a long mesentery becomes entrapped over an atrophic liver and may cause abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and obstruction.6,7 Patients who have symptomatic Chilaiditi syndrome are often successfully treated conservatively with nasogastric decompression, fluid resuscitation, and bed rest.7 However, if conservative treatment fails, laparoscopic colopexy or colectomy may be required.8

Small bowel obstruction secondary to Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome and Chilaiditi syndrome is a rare occurrence. Frequent causes of SBO in a virgin abdomen are inguinal hernia, internal hernia, gallstone ileus, malignancy, foreign body, spontaneous adhesion, Meckel's diverticulum, intussusception, congenital remnants, and inflammatory bowel disease. If the patient is afebrile and without peritoneal irritation, initial management is conservative with decompression, hydration, and observation. Computed tomography is helpful in the diagnosis of underlying pathology, although frequently the patients that require surgical decompression lack a definitive preoperative diagnosis. As with our patient, laparoscopy is an excellent option in diagnosing and treating these patients. Although the minimally invasive costs are similar to those of the open procedure, the patients benefit from quicker recovery, decreased morbidity, reduced hospital stay, and fewer subsequent adhesions.

CONCLUSION

The laparoscopic approach is ideal in patients with SBO who do not have extensive prior abdominal surgeries. The cause can be confirmed, and frequently unexpected pathology can be addressed using advanced laparoscopic skills. Our patient exhibited obstructive symptoms from right upper quadrant adhesions most likely due to Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome, although the definitive cause of her SBO remains undetermined. Unfortunately, many of these patients have no documented history of pelvic inflammatory disease, and the diagnosis is made at exploration by finding adhesions between her diaphragm and liver. In any case, the successful laparoscopic management of this patient lends credence to the laparoscopic management of SBO.

References:

- 1.Whang EE, Ashley SW, Zinner MJ. Small Intestine. In: Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, Dunn DL, Hunter JG, Pol-lock RE. eds. Schwartz's Principles of Surgery. 8th ed New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies Inc; 2005;1027–1030 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsao KJ, St. Peter SD, Valusek PA, et al. Adhesive small bowel after appendectomy in children: comparison between laparoscopic and open approach. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(6):939–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sweet RL, Gibbs RS. Infectious Diseases of the Female Genital Tract. 4th ed Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002;75–76, 382–383 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perry CP, Howard FM. Adhesions. In: Howard FM, Perry CP, Carter JE, El-Minawi AM. eds. Pelvic Pain Diagnosis & Management. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000;91–97 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abul-Khoudoud OR, Khabbaz AY, Butcher CH, Farha MJ. Mechanical partial small bowel obstruction in a patient with Fitz-Hugh-Curtis Syndrome. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2001;11(2):111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Havenstrite KA, Harris JA, Rivera DE. Splenic flexure volvulus in association with Chilaiditi syndrome: report of a case. Am Surg. 1999;65(9):874–876 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orangio GR, Fazio VW, Windelman E, McGonagle BA. The Chilaiditi syndrome and associated volulus of the transverse colon: an indication for surgical therapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29(10):653–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alva SShetty-Alva N, Longo WE. Image of the month: Chilaiditi sign or symptom. Arch Surg. 2008;143(1):93–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]