Abstract

T-tube choledochotomy has been an established practice in common bile duct exploration for many years. Although bile leaks, biliary peritonitis, and long-term postoperative strictures have been reported and are directly associated with the placement or removal of the T-tube, the severity of these complications may often be underestimated by surgeons. We present the case of a 31-year-old male patient who developed biliary peritonitis and septic shock after removal of a T-tube and illustrate one of the catastrophic events that may follow such procedures. Literature shows that these complications may occur more frequently and have higher morbidity and mortality than other less invasive procedures. This article reviews the advances in laparoscopic and endoscopic techniques, which provide alternative therapeutic approaches to choledocholithiasis and allow the surgeon to avoid having to perform a choledochotomy with T-tube drainage.

Keywords: T-tube choledochotomy, Biliary peritonitis, Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

INTRODUCTION

T-tube choledochotomy for common bile duct (CBD) exploration was first described more than 100 years ago and has since been used by surgeons around the world for the management of biliary lithiasis. When laparoscopic cholecystectomy became the gold standard of treatment for calculous cholecystitis, laparoscopic techniques for CBD exploration became necessary and T-tube choledochotomy continued to be a useful approach. Presently, however, many other options exist for the management of CBD stones, which do not require T-tube placement (transcystic exploration, intraoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [ERCP], postoperative ERCP, and primary closure of the CBD). Because the laparoscopic placement of a T-tube may be technically demanding and because both placement and removal of T-tubes may lead to severe complications, surgeons must question whether this should continue to be a routine approach or whether other, less morbid, techniques may be used. We present a case of severe biliary peritonitis after T-tube removal, which illustrates the grave consequences that may occur from this procedure and discuss other reported complications as well as therapeutic alternatives.

CASE REPORT

Four weeks after an uneventful laparoscopic cholecystectomy with CBD exploration and T-tube placement, a 31-year-old patient attended his follow-up visit where a cholangiogram showed no contraindications for removal of the T-tube. Immediately upon removal, the patient experienced severe abdominal pain and tachycardia that did not respond to analgesics and he required admission to the hospital. An abdominal ultrasound showed a small fluid collection that was not considered to merit percutaneous drainage. After 24 hours of conservative management, the patient still complained of abdominal pain, and therefore an ERCP was indicated to identify and treat the site of a possible bile leak. ERCP showed a small rupture at the point where the fistulous tract joined the abdominal wall and contrast material leaking into the abdominal cavity (Figure 1). Endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed, and a biliary stent was placed in an attempt to reduce leakage through the ruptured fistulous tract. Fortyeight hours after the ERCP, the patient's condition worsened, with fever, diaphoresis, tachycardia, leucocytosis, and an acute abdomen occurring. An emergency laparoscopy showed a severe generalized biliary-purulent peritonitis that required extensive lavage and placement of abdominal drains. The rupture of the fistulous tract was sutured to avoid further bile leakage. During the procedure, the patient developed hemodynamic instability and bacteremia and had to be transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). The patient's condition progressed to severe respiratory distress and systemic inflammatory response syndrome due to septic shock and required 4 weeks of aggressive treatment in the ICU with ventilatory support, multiple antibiotics, vasoactive agents, and activated C protein. Culture of the peritoneal fluid showed a multiresistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The patient was eventually discharged 6 weeks after the removal of the T-tube.

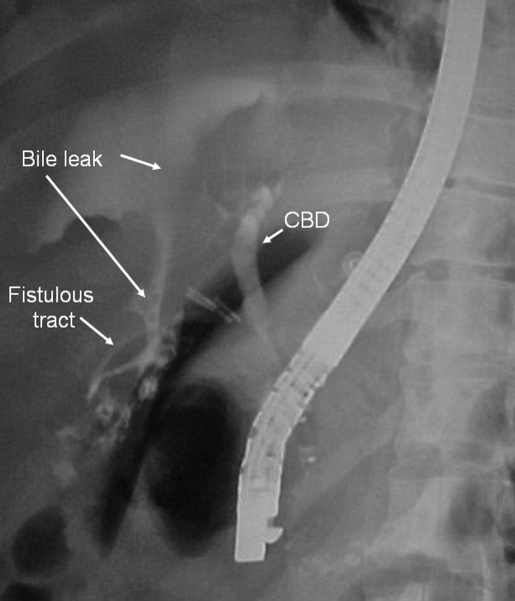

Figure 1.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed bile leakage at the ruptured fistulous tract.

DISCUSSION

This case is a clear example of the catastrophic events that may occur after T-tube removal in a patient who had previously undergone an uneventful laparoscopic cholecystectomy and T-tube choledochotomy. Initial conservative management of an apparently small bile leakage was unsuccessful. The ultrasound findings of a small fluid collection mislead clinical judgment and delayed a more aggressive approach such as percutaneous drainage. Endoscopic treatment with sphincterotomy and stent placement, which is an accepted method for the resolution of such cases,1 also failed to control the problem. Fortunately, the abdominal lavage procedure and the management in the ICU eventually led to the patient's recovery, but only after high health and financial costs resulted from the removal of the T-tube.

Cholecystectomy due to gallstone disease remains one of the most common surgical procedures performed, and CBD exploration is frequently required for concomitant choledocholithiasis. The incidence of choledocholithiasis in patients who undergo cholecystectomy increases with age, and in those with acute cholecystitis and jaundice it may reach up to 70%.2,3 Unsuspected CBD stones (found in routine intraoperative cholangiography) are present in approximately 5% of cases.4 In 1889, Thornton described the first successful surgical CBD exploration,5 and since then, treatment for choloedocholithiasis has consisted mainly of stone extraction through a choledochotomy with placement of a T-tube for postoperative drainage and radiologic control. In the 1970s, the endoscopic approach to biliary stones became popular due to the good extraction results and low incidence of complications. In the 1990s, when laparoscopic cholecystectomy became the gold standard of treatment for calculous cholecystitis, laparoscopic CBD exploration became necessary, and T-tube choledochotomy continued to be used as a standard procedure.6 The placement of a T-tube during open cholecystectomy is usually a simple procedure that is used to control biliary drainage and can be helpful for radiologists, once the fistulous tract is formed, to remove stones that may remain in the biliary ducts. Laparoscopic choledochotomy, although technically more demanding, is also commonly performed by surgeons who are familiar with advanced laparoscopic procedures. Latex rubber tubes are usually preferred to other materials,7 and construction of small and flexible T ends is thought to facilitate placement and removal of the tube.

In our review of the literature regarding T-tube complications, we found that most of the reports are isolated case presentations, and very few are larger case series that focus on this problem. This leads us to believe that, although T-tubes continue to be placed frequently in many countries, the complications associated with their placement or removal may be underestimated. According to some authors, the difference in complication rates does not seem to be related to whether the approach is open or laparoscopic (15.5% vs. 13.8%, respectively),8 but rather to the presence and removal of the tube. Complications that have been reported may occur with the T-tube in situ. These include fluid and electrolyte imbalance, early dislodgment, tube dislocation, tube retention, and bacteremia.9–15 Those associated with removal of the T-tube include bile leaks, biliary peritonitis, sepsis, and death.8,9,16–18 Most authors conclude that these complications result in longer hospital stay, increased rate of reoperations, and higher financial costs.

When reviewing larger series of CBD exploration, it has been found that complications are often related directly to the T-tube choledochotomy with reports showing approximately 2% to 15% morbidity and 1% to 6% mortality in these cases (Table 1). Most severe complications are due to rupture of the CBD or fistulous tract. Although the cause of this is not well understood, it could be related to inadequate placement, incomplete fistulous tract formation, or forced removal. The incidence of bile leakage caused by removal of the T-tube has been reported from 0.45% to 10%,19 and that of biliary peritonitis may be higher than expected.7 To prevent bile leakage due to T-tube removal, the surgeon should pay particular attention to the technical aspects of placement, such as assuring small and flexible T ends, care not to suture the tube to the bile duct, and adequate percutaneous exteriorization of the tube. Removal of the tube is usually an outpatient procedure that is recommended at least 15 days after its placement, once a proper fistulous tract has been formed and the risk of bile leaks and choledochal rupture is reduced. Prolonged tube placement carries the risk of bacteremia after removal.9

Table 1.

T-tube Related Complications

Morbidity and mortality of bile peritonitis due to biliary surgery have been reported to be as high as 57% and 14%, respectively.20 Treatment of biliary peritonitis varies according to the severity of the case and may include from simple procedures, such as percutaneous drainage and endoscopic nasobiliary drainage, to more complex ones, such as endoscopic sphincterotomy with endobiliary stent placement, re-operation with T-tube reinsertion, or reoperation with bilioenteric reconstruction.16 Early recognition is essential for adequate treatment, and some authors have suggested performing a fistulogram immediately after removal of the T-tube to confirm the presence or absence of a leak.21

With the advent of other, less-invasive techniques, the risks and benefits of T-tube choledochotomy must now be compared with the risks and benefits of other therapeutic measures. The management of CBD stones can usually be determined by whether the diagnosis is made preoperatively, transoperatively, or postoperatively (Table 2). In all cases, options that avoid choledochotomy and T-tube placement are possible. Note also, that with the widespread performance of these therapeutic measures, the need for postoperative radiologic stone extraction is becoming less frequent, and therefore, this indication for T-tube placement may not be necessary in the future.

Table 2.

Treatment Options for Choledocholithiasis

| Diagnosis of CBD* Stones | Treatment Options |

|---|---|

| Preoperative (patient with jaundice, bile duct dilatation or history of biliary pancreatitis) | 1. ERCP* followed by cholecystectomy |

| 2. Programmed cholecystectomy with CBD exploration (open or laparoscopic) | |

| Transoperative (unsuspected finding during transoperative cholangiography) | 1. CBD exploration and T-tube placement (open or laparoscopic) |

| 2. CBD exploration with primary closure (open or laparoscopic, with or without endoscopic sphincterotomy) | |

| 3. Transoperative ERCP | |

| 4. Cholecystectomy and guide wire placement in the CBD followed by postoperative ERCP | |

| Postoperative (retained CBD stone) | 1. ERCP |

| 2. Surgical CBD exploration (open or laparoscopic) | |

| 3. Radiologic extraction through T-tube fistulous tract |

CBD = common bile duct; ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

ERCP and sphincterotomy, although shown in some studies to be associated with complications and death, have proven to be effective and safe methods for CBD stone extraction. In the hands of experienced endoscopists, they have a high success rate with low complications.22 In some cases, however, ERCP may have certain limitations, such as the presence of multiple intrahepatic stones, stones >1.5 cm, the presence of a nondilated CBD, or a concomitant duct stenosis. In these circumstances, a surgical approach will be required.

Minimally invasive surgery provides options to explore the CBD without having to place a T-tube. Laparoscopic transcystic exploration with biliary balloon catheters or Dormia baskets should always be attempted first and when not feasible, due to the presence of large or impacted stones, pneumatic dilatation of the cystic duct and use of a choledochoscope may be required.23 Success of laparoscopic CBD exploration and stone clearance has been reported at rates of 85% to 95% with impacted stones being the most likely cause of failure. In these difficult cases, placement of a transcystic stent or guidewire followed by postoperative ERCP may be a good option to avoid choledochotomy and T-tube placement.24

Since laparoscopic CBD exploration requires less manipulation and devascularization of the bile duct, smaller and more precise choledocotomies can be performed. This has led some authors25,26 to advocate the use of primary closure of the CBD after choledochotomy. Primary closure can be complimented with transcystic biliary decompression27 or endoscopic sphincterotomy and endobiliary stenting24 to reduce the risk of bile leakage. Although this method has not yet been widely accepted due to fear of complications, recent Cochrane reviews28,29 were unable to find sufficient evidence to recommend T-tube placement over primary closure of the CDB in either open or laparoscopic procedures. Although not statistically significant, this interesting review does show that the deaths of the patients in the T-tube group were directly related to surgery and sepsis and that bile peritonites was higher (2.9%) in the T-tube group than in the primary closure group (1%).29

Finally, although most long-term biliary strictures are due to iatrogenic events during cholecystectomy or other hepatobiliary procedures, some have been associated with severe scarring at the site of a previous T-tube choledochotomy.30 It has already been mentioned that the laparoscopic approach, in experienced hands, may cause less devascularization, and it allows for smaller choledochotomies, which will probably reduce these scarring effects and the number of postoperative strictures. Needless to say, this risk could probably be completely eliminated if the choledochotomy is avoided all together.

When analyzing the differences between surgical and endoscopic treatment of biliary lithiasis, a Cochrane review31 found that laparoscopic bile duct clearance is providing a safe and efficient method with no statistical difference in morbidity or mortality compared with ERCP in specialized centers (Table 3). However, it is difficult to establish a comparison between the morbidity and mortality rates of laparoscopic T-tube choledochotomy and ERCP for the treatment of bile duct stones because most studies on laparoscopic CBD exploration report on the transcystic approach and not on the more demanding choledochotomy procedure.31

Table 3.

Comparison Between ERCP and Surgical Treatment of Bile Duct Stones

| Procedures Compared | Morbidity* | Mortality* (Deaths/Patients) |

|---|---|---|

| ERCP vs open surgical bile duct clearance | NS | ERCP: 10/361 |

| Surgery: 5/372 | ||

| Preoperative ERCP vs laparoscopic surgical bile duct clearance | NS | ERCP: 3/178 |

| Surgery: 2/169 | ||

| Postoperative ERCP vs laparoscopic surgical bile duct clearance | NS | NS |

NS = no statistical significance; ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

CONCLUSION

Many reports found in the literature show that both placement and removal of the T-tube may have complications that result in longer hospital stay, increased rate of reoperations, higher financial costs, and some degree of deaths. Because most of these reports are isolated case descriptions and only a few of them present large series of patients, the morbidity and mortality associated with the use of T-tube choledochotomy in the treatment of bile duct lithiasis may be underestimated.

This procedure has been performed for many years and continues to be a useful resource in other areas of hepatobiliary surgery, but the tendency towards less invasiveness, in all areas of general surgery, should prompt surgeons to consider other possibilities with equal or better results for the resolution of choledocholithiasis. Although the authors of this article are experienced in laparoscopic CBD exploration and had not previously had complications associated with T-tube choledochotomy, this case served to encourage us to reconsider the therapeutic options in future cases. We now believe that a precise case selection is necessary before determining which procedure will be better for each patient. Clinical findings and pre-existing conditions, intraoperative findings and anatomical or inflammatory variations, surgical and endoscopist experience and success rate or even technological availability are all important factors that should be taken into consideration to provide the best possible treatment.

Contributor Information

Denzil Garteiz Martínez, Surgery Department, Angeles Lomas Hospital, Mexico..

Alejandro Weber Sánchez, Surgery Department, Angeles Lomas Hospital, Mexico..

María Elena López Acosta, Gastroenterology and Endoscopy, Department Angeles Lomas Hospital, Mexico..

References:

- 1.Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Paroutoglou G, et al. The role of endoscopic treatment in postoperative bile leaks. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53(68):166–170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Havard C. Operative cholangiography. Br J Surg. 1970;57:797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schreurs WH, Juttmann JR, Stuifbergen WN, Oostvogel HJ, van Vroonhoven TJ. Management of common bile duct stones: selective endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and endoscopic sphincterotomy: short- and long-term results. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(7):1068–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzgibbons RJ, Gardner GC. Laparoscopic surgery and the common bile duct. WJ Surg. 2001;25(10):1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis H. Cholecystostomy and cholecystectomy. In: Maingot's Abdominal Operations. Norwalk, Connecticut: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lien HH, Huang CC, Huang CS, et al. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration with T-tube choledochotomy for the management of choledocholithiasis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2005;15(3):298–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbett CR, Fyfe NC, Nicholls RJ, Jackson BT. Bile peritonitis after removal of T-tubes from the common bile duct. Br J Surg. 1986;73(8):641–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wills VL, Gibson K, Karihaloot C, Jorgensen JO. Complications of biliary T-tubes after choledochotomy. ANZ J Surg. 2002;72(3):177–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul ZA, Jonnalagadda R, Antonio C. A case of T-tube dislocation Chir Ital. 58(4):513–518, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angel Mercado M, Chan C, Orozco H, et al. Bile duct injuries related to misplacement of “T tubes.” Ann Hepatol. 2006;5(1):44–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heikkinen M, Poikolainen E, Kaukanen E, Paakkonen M. Removing a biliary T-tube and retained stones by ERCP. A case report. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52(66):1666–1667 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colovic R, Radak V, Grubor N, Matic S. Slip of the T tube within the common bile duct–a little known complication of the T tube drainage Srp Arh Celok Lek. 133(3–4):138–141, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakorafas GH, Stafyla V, Tsiotos GG. Biliary peritonitis due to fistulous tract rupture following a T-tube removal. N Z Med J. 2005;118(1217):U1522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillatt DA, May RE, Kennedy R, Longstaff AJ. Complications of T-tube drainage of the common bile duct. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1985;67(6):370–371 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horgan PG, Campbell AC, Gray GR, Gillespie G. Biliary leakage and peritonitis following removal of T tubes after bile duct exploration. Br J Surg. 1989;76(12):1296–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang JM, Yu SA, Shen W, Zheng ZD. Pathogenesis and treatment to postoperative bile leakage: report of 38 cases. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4(3):441–444 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maghsoudi H, Garadaghi A, Jafary GA. Biliary peritonitis requiring reoperation after removal of T-tubes from the common bile duct. Am J Surg. 2005;190(3):430–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gharaibeh KI, Heiss HA. Biliary leakage following T-tube removal. Int Surg. 2000;85(1):57–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang GQ, Zhang YH, Shen CM, Liang JR. Combined use of choledochoscope and duodenoscope in treatment of bile peritonitis after removal of T-tube. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006;5(4):624–626 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cartu D, Georgescu I, Nemes R, et al. Postoperative biliary peritonitis– diagnosis and treatment difficulties. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2006;101(2):169–173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazaridis Ch, Papaziogas B, Patsas A, et al. Detection of tract formation for prevention of bile peritonitis after T-tube removal. Case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2005;105(2):210–212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron TH, Harewood GC. Endoscopic balloon dilation of the biliary sphincter compared to endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy for removal of common bile duct stones during ERCP: a metaanalysis of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(8):1455–1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyass S, Phillips EH. Laparoscopic transcystic duct common bile duct exploration. Surg Endosc. 20(Suppl 2):S441–S445, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karvounis E, Griniatsos J, Arnold J, Atkin G, Isla AM. Why does laparoscopic common bile duct exploration fail? Int Surg. 2006;91(2):90–93 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamazaki M, Yasuda H, Tsukamoto S, et al. Primary closure of the common bile duct in open laparotomy for common bile duct stones. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13(5):398–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ha JP, Tang CN, Siu WT, Chau CH, Li MK. Primary closure versus T-tube drainage after laparoscopic choledochotomy for common bile duct stones. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51(60):1605–1608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei Q, Hu HJ, Cai XY, Li LB, Wang GY. Biliary drainage after laparoscopic choledochotomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(21):3175–3178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gurusamy K, Samraj K. Primary closure versus T-tube drainage after laparoscopic common bile duct stone exploration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(1):CD005641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gurusamy K, Samraj K. Primary closure versus T-tube drainage after open common bile duct exploration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(1):CD005640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braasch J. Postoperative strictures of the bile ducts. In: Main-got's Abdominal Operations. Norwalk, Connecticut: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin DJ, Vernon DR, Toouli J. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(2):CD003327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]