Abstract

Background:

Splenectomy has 50% to 70% long-term efficacy for immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). In some patients, relapse is due to the presence of residual accessory splenic tissue.

Methods:

A 44-year-old male had ITP since 1983 with splenectomy in 1985. He had a transient response, but then developed severe thrombocytopenia refractory to multiple modalities for 20 years. An accessory spleen was first visualized in 2000.

Results:

A laparoscopic accessory splenectomy was performed without difficulty. The patient had an initial response with a significant increase in platelet count. Although over time the thrombocytopenia recurred, there has been a long-term benefit in that the patient is on much lower doses of prednisone to maintain an adequate platelet count.

Conclusion:

The finding of accessory splenic tissue after prior splenectomy may be an increasingly common problem in patients with recurrent ITP. Although reported response rates for resection of residual splenic tissue vary, the availability of a safe, less morbid, minimally invasive approach makes the decision to operate easier.

Keywords: Thrombocytopenia, ITP (immune thrombocytopenia), Splenectomy, Laparoscopic surgery

INTRODUCTION

Excluding trauma, immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is the most common indication for splenectomy in the United States.1 In adult patients, splenectomy is an attractive therapeutic option for those who fail to respond to 4 weeks to 6 weeks of medical therapy with steroids or other agents, who require toxic medication doses to maintain remission, or who relapse following an initial response to medical therapy. This therapy is highly efficacious because the spleen is the major site for clearance of antibody-coated platelets and also a primary site for platelet autoantibody production.2 Numerous prospective and retrospective studies have found early response rates between 80% to 89% and long-term remission rates of 50% to 70% following splenectomy for treatment of ITP.3–6 Patients failing splenectomy generally require long-term immunosuppressive therapy. A subgroup of patients that initially responded to splenectomy will have residual accessory splenic tissue discoverable at relapse. As illustrated by our case, these patients may be candidates for further surgical therapy, and the decision to operate may be made easier by the availability of minimally invasive laparoscopic techniques.

METHODS

A 44-year-old male from Argentina presented with ITP in 1983 and underwent splenectomy in 1985. There was an adequate response for 2 years, but then bleeding and severe thrombocytopenia recurred. The disease proved resistant to multiple attempted therapeutic interventions, including danazol, pulse high-dose dexamethasone, vincristine, cyclosphosphamide, dapsone, mycophenolate, colchicine, and rituximab. There would be very brief (few days) partial responses to high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. Platelets were usually less than 10x 109/L, and prednisone 20 mg to 30 mg daily was continued because it seemed to reduce bleeding manifestations. These manifestations were mainly bruising and gum bleeding, but diverticular bleeding on one occasion required red blood cell transfusions. In 2000, a small accessory spleen was detected on computed tomographic (CT) scan, and this was treated with small doses of radiotherapy.

The patient was evaluated in Houston in March 2005, at which time platelet counts were 5x109/L and 17x109/L. Peripheral blood smear showed few acanthocytes and only very rare Howell-Jolly bodies. A CT scan and technetium radionucleide liver-spleen showed an accessory spleen that had grown to about 38 mm (Figure 1). After discussion of therapeutic options, a decision was made to proceed with a laparoscopic accessory splenectomy. The patient was pretreated with IVIG 2 g/kg, which raised the preoperative platelet count to 84x109/L. At laparoscopic surgery, an accessory spleen measuring 4.2x3.5x3.2 cm was identified and easily removed (Figure 2); histology demonstrated splenic parenchyma with sinusoidal congestion and expanded red pulp (Figure 3).

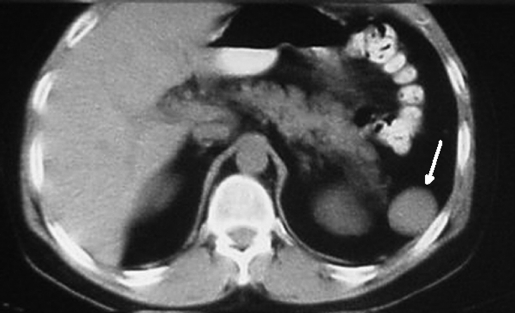

Figure 1.

Computed tomographic scan of the abdomen demonstrating accessory spleen (arrow).

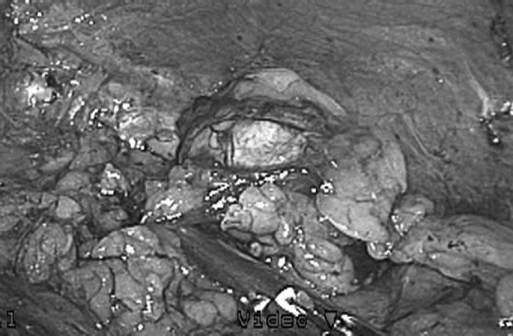

Figure 2.

Intraoperative view of accessory spleen.

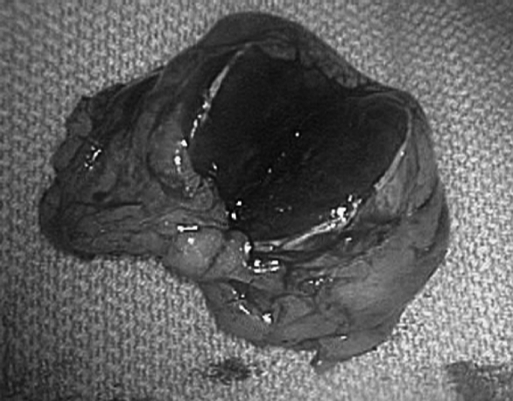

Figure 3.

Bi-valved accessory spleen.

RESULTS

The postoperative course was free of complications with diet resumed on postoperative day 1 and discharge on postoperative day 2. Platelets rose from 77x109/L to 151x109/L over the next few days. Unfortunately, platelets fell back to 20x109/L after 2 months; in recent months, platelet counts average 20x109/L with the patient on 10mg prednisone daily. Therapy for H. pylori failed, and experimental thrombopoietic stimulators are under consideration.

DISCUSSION

Minimally invasive surgery is associated with reduced postoperative pain, earlier return to normal activity, improved cosmesis, and lower hospital costs compared with open surgery to treat similar disorders.7,8 Because laparoscopic cholecystectomy was shown to meet these criteria in the late 1980s and early 1990s,9 minimally invasive surgical techniques have been applied to a variety of abdominal and thoracic procedures. Since its introduction in 1992, laparoscopic splenectomy has been shown to be effective and safe.10,11 The most common indication for elective splenectomy is ITP. Unfortunately, even when surgery successfully achieves platelet count remission, there is no guarantee that the disease will not recur. A review of the literature shows ITP recurrence following splenectomy to range between 18% and 38%.12–16 In a significant number of these patients, residual accessory splenic tissue can be found.

Accessory spleens have been encountered during open splenectomies in 14% to 30% of patients.17 Targarona et al18 reported finding an accessory spleen in 33% of the patients who did not have clinical improvement after laparoscopic splenectomy for treatment of ITP. Multiple modalities for identification of accessory splenic tissue have been reported. Abdominal CT scans will identify accessory splenic tissue in the majority of cases. However, if there is any uncertainty in the diagnosis based on CT scan, preoperative nuclear medicine scintigraphy using heat-damaged Tc99m-labeled red blood cells can be added to the workup.19 Finally, intraoperative gammaprobe guidance after injection of Tc99m-labeled red blood cells can also be used to identify small focuses of splenic tissue during laparoscopic exploration.20,21

The ultimate question then is whether removal of accessory splenic tissue makes a difference in ITP patients who have relapsed after splenectomy. The literature provides a wide disparity in the efficacy of repeat surgery. In open accessory splenectomy, the response has been reported in 26.7% to 75%.22,23 Similar findings are seen with the laparoscopic approach.19,24,25 Although a complete response following accessory splenectomy may not be possible, most patients will realize some benefit from the intervention because of decreased requirements for systemic immunosuppressive therapies. A review of the literature confirms our experience that laparoscopic accessory splenectomy is technically feasible. Szold et al24 reported successful laparoscopic accessory splenectomy in 8 of 8 patients. All patients were discharged on postoperative day one with no complications. Other studies confirm that laparoscopic accessory splenectomy is safe and effective. Morris et al25 reported no conversion to open surgery and no complications with all discharges on postoperative day 1. Therefore, it seems that the risk benefit ratio favors laparoscopic resection of residual accessory splenic tissue in patients with recurrent ITP.

CONCLUSION

Although the initial hematologic response to laparoscopic accessory splenectomy in this particular case was brief, there appears to be some degree of long-lasting benefit in that the patient is now on lower doses of prednisone. This case documents that laparoscopic resection of residual splenic tissue in patients with recurrent ITP is safe and well-tolerated and should be strongly considered in patients who are refractory to other therapeutic modalities.

References:

- 1.Vavra A, Sweeney JF. Laparoscopic splenectomy – a review. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2004;14:347–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lechner K. Management of adult immune thrombocytopenia. Rev Clin Exp Hematol. 5:222–35, 2001; discussion 311–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katkhouda N, Manhas S, Umbach TW, Kaiser AM. Laparoscopic splenectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2001;11:383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman RL, Fallas MJ, Carroll BJ, Hiatt JR, Phillips EH. Laparoscopic splenectomy for ITP. The gold standard. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:991–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bresler L, Guerci A, Brunaud L, et al. Laparoscopic splenectomy for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: outcome and long-term results. World J Surg. 2002;26:111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pace DE, Chiasson PM, Schlachta CM, Mamazza J, Poulin EC. Laparoscopic splenectomy for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Surg Endosc. 2003;17:95–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katkhouda N, Grant SW, Mavor E, et al. Predictors of response after laparoscopic splenectomy for immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:484–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh RM, Heniford BT, Brody F, Ponsky J. The ascendance of laparoscopic splenectomy. Am Surg. 2001;67:48–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotton PB, Baillie J, Pappas TN, Meyers WS. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the biliary endoscopist. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:94–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fass SM, Hui TT, Lefor A, Maestroni U, Phillips EH. Safety of laparoscopic splenectomy in elderly patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am Surg. 2000;66:844–847 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park AE, Birgisson G, Mastrangelo MJ, Marcaccio MJ, Witzke DB. Laparoscopic splenectomy: outcomes and lessons learned from over 200 cases. Surgery. 2000;128:660–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pace DE, Chiasson PM, Schlachta CM, Mamazza J, Poulin EC. Laparoscopic splenectomy for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Surg Endosc. 2003;17:95–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akwari OE, Itani KM, Coleman RE, Rosse WF. Splenectomy for primary and recurrent immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Current criteria for patient selection and results. Ann Surg. 1987;206:529–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Facon T, Caulier MT, Fenaux P, et al. Accessory spleen in recurrent chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol. 1992;41:184–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu JM, Lai IR, Yuan RH, Yu SC. Laparoscopic splenectomy for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Surg. 2004;187:720–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berends FJ, Schep N, Cuesta MA, et al. Hematological long-term results of laparoscopic splenectomy for patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a case control study. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:766–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coon WW. Surgical aspects of splenic disease and lymphoma. Curr Probl Surg. 1998;35:543–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Targarona EM, Espert JJ, Balagué C, et al. Residual splenic function after laparoscopic splenectomy: a clinical concern. Arch Surg. 1998;133:56–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velanovich V, Shurafa M. Laparoscopic excision of accessory spleen. Am J Surg. 2000;180(1):62–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antevil J, Thoman D, Taller J, Biondi M. Laparoscopic accessory splenectomy with Intraoperative gamma probe localization for recurrent idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;12:371–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirshtein B, Lantsberg S, Hatskelzon L. Laparoscopic accessory splenectomy using intraoperative gamma probe guidance. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:205–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verheyden CN, Beart RW, Jr., Clifton MD, Phyliky RL. Accessory splenectomy in management of recurrent idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Mayo Clin Proc. 1978;53:442–446 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudowski WJ. Accessory spleens: clinical significance with particular reference to the recurrence of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. World J Surg. 1985;9:422–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szold A, Kamat M, Nadu A, Eldor A. Laparoscopic accessory splenectomy for recurrent idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura and hemolytic anemia. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(8):761–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris KT, Horvath KD, Jobe BA, Swanstrom LL. Laparoscopic management of accessory spleens in immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Surg Endosc. 1999;13(5):520–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]