Abstract

Objective:

Robotic technology has been used in a variety of surgical procedures for its 3D magnification and precision. Minimally invasive techniques have already become common in neurosurgery; however, robotic-assisted procedures in neurosurgery are still a relatively new frontier. This report describes the first use of robotic technology to resect a left thoracolumbar neurofibroma.

Case Report:

A 19-year-old male with a family history of neurofibromatosis was diagnosed with a suspected 3-cm x 4-cm neurofibroma in the T12-L1 left paraspinal area. His only complaint was back pain requiring narcotic analgesics. He had no other findings on physical examination or laboratory/radiologic workup.

Methods:

After consulting urologic robotic surgeons, it was agreed to use the da Vinci robot (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA) for the resection of this mass. Following retroperitoneal laparoscopic access, the urologic surgeons opened the diaphragm and began the initial mobilization of the mass laparoscopically. The robot was docked, and the neurosurgeon operated the robot at the console to resect the mass from its nerve origin. There were no complications, and the mass, a confirmed neurofibroma, was completely removed. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 2; his back pain resolved, requiring no analgesia by the end of the first postoperative week.

Conclusion:

This case provides early evidence that robotic assistance can be successfully used for the resection of a paraspinal neurofibroma.

Keywords: Neurofibroma, Retroperitoneal, Robotic-Assisted, Laparoscopic, Thoracolumbar, Transdiaphragmatic

INTRODUCTION

Neurofibromatosis-1 (NF-1) is an autosomal dominant disorder with an incidence of almost 1 in 3000; overall, 50% of patients have a family history consistent with this disorder.1 The major features include multiple neural tumors (neurofibromas), numerous pigmented skin lesions (which may include café au lait spots), and pigmented hamartomas affecting the iris (Lisch nodules). Approximately, 95% of these patients will develop cutaneous or subcutaneous neurofibromas, and 30% will develop plexiform neurofibromas.1 Laparoscopic removal of retroperitoneal neurofibromas has been described in only 3 patients.2,3 The 12X magnification afforded by the laparoscope appeared to facilitate the careful dissection around the nerves.

Recently, the da Vinci surgical robot has entered the surgical realm, most notably in urology for the surgical treatment of prostate cancer. The 6 degrees of freedom afforded by the robot instrumentation, combined with the 3D high-definition image, and rock steady operating arms, allow the surgeon to operate in an extremely precise, meticulous manner heretofore unavailable. In addition, the magnification provided by the endoscope varies from 12X to 40X depending on its proximity to the target tissue. Application of this technology for excision of a neurofibroma has appeared in the literature on only one occasion: in 2003, a mediastinal neurofibroma was removed by cardiothoracic surgeons using a totally endoscopic approach with three 1-cm incisions for the robotic ports.4 Herein, we report the first case of a robotic-assisted laparoscopic resection of a thoracolumbar neurofibroma via a retroperitoneoscopic laparoscopic approach, making it the first case of a paraspinal tumor removed robotically.

CASE REPORT

A 19-year-old male with a history of neurofibromatosis type I presented with a 2-year history of back pain located on the left side of his thoracolumbar paraspinal area with no radiation. The pain progressively worsened over 2 years increasing significantly the 2 months prior to presentation resulting in the use of narcotic analgesia.

The patient had a past medical history positive for a melanoma, which was excised from his back 3 months before presentation. Family history revealed the patient's mother has a diagnosis of NF-1, and a history of multiple tumors including neurofibromas and a melanoma.

Physical examination revealed a slender Caucasian male (5′9”, 153 pounds), with multiple pigmented nevi on his skin. He had a 3-cm x 3-cm scar in the left mid/upper back area lateral to his spine, where his melanoma had been excised. He had some left costovertebral angle tenderness. The remainder of his physical examination, including a detailed neurological evaluation, was unremarkable.

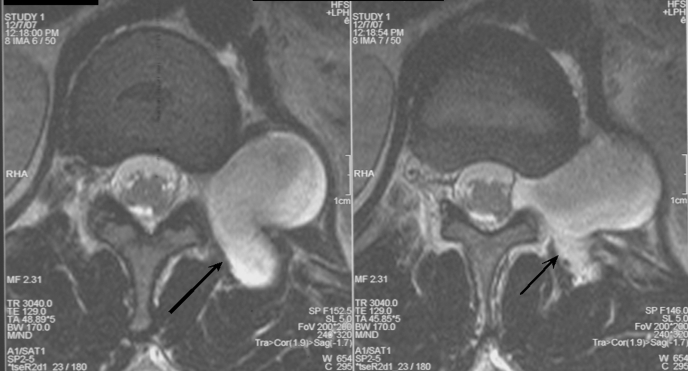

CT angiography showed a 4.3-cm x 2.9-cm paravertebral mass at the T12-L1 junction, with a slightly widened neural foramen. The mass appeared adjacent to the upper pole of the kidney, albeit posterior to the inferior left hemidiaphragm. An MRI of the chest revealed a 3.7-cm x 3.0-cm lobulated paraspinal mass at T12-L1 posterior to the upper pole of the left kidney. MRI scan of the thoracic spine with and without contrast revealed the mass to be arising from a widened neural foramen at T12-L1 with no extension into the spinal canal with the mass projecting laterally behind the left kidney and posteriorly into paraspinal muscles. The mass enhanced uniformly with contrast, consistent with a neurofibroma (Figures 1, 2).

Figure 1.

Abdominal CT scan revealing paravertebral mass (black arrow) adjacent to the upper pole of the left kidney, posterior to the inferior left hemidiaphragm (white curve and arrow).

Figure 2.

T1-weighted MRI of mass originating at T12-L1 neural foramen.

Spinal angiography revealed the dual supply of the inferior spinal cord by 2 origins of the artery of Adamkiewicz, at both T10 and L2 on the left.

Surgical excision of the mass was offered for pain relief and diagnosis. Both standard open and minimally invasive procedures were discussed. Because of the extraspinal retrophrenic/retrorenal location of the mass, a minimally invasive approach was chosen. Urology was consulted regarding the feasibility of accessing the tumor via a retroperitoneal laparoscopic approach and the possibility of using the da Vinci robot (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA) for tumor excision. After extensive discussion of the risk and benefits with the patient and his family, the minimally invasive robotic approach was selected with full knowledge of a possible conversion to a standard open approach.

Operative Procedure

With the patient prepared and draped in a right lateral decubitus position, a 12-mm incision was made off of the tip of the twelfth rib. A Veress needle was then used to insufflate the retroperitoneum. An Ethicon X-Cel 12-mm optical port (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) was placed under direct endoscopic control into the pneumoretroperitoneum. The retroperitoneum was further expanded by using a dissection balloon (U. S. Surgical Inc., Norwalk, CT). Two 8-mm robotic ports were then placed subcostally, one in the posterior axillary line, and the other in the anterior axillary line (Figure 3). A 12-mm port was placed above the iliac crest in the anterior axillary line, and a 5-mm port was placed just above and medial to it.

Figure 3.

Docked robot, with 2 working arms, one arm attached to the endoscope, and 2 additional assistant's ports.

The psoas muscle was identified and dissected medially and superiorly, until the diaphragm was noted. The kidney, within Gerota's fascia, was mobilized along its posterior surface and retracted medially. Careful inspection of the retroperitoneum then revealed the mass, pushing the diaphragm upward. The diaphragm was incised vertically over the mass, and the anterior surface of the mass was dissected until its upper and lower margin could be clearly discerned (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Initial view of tumor through robotic endoscope with bipolar serrated graspers in the left robotic hand, monopolar electrosurgical scissors in the right robotic hand, and assistant operated irrigation/suction inferiorly.

The da Vinci robot was then docked (Figure 3). The neurosurgeon then sat at the robotic console, while the urologic surgeon assisted at the side of the operating table. The robotic endoscope (12 mm) and 2 robotic arms (8 mm) were placed through the aforedescribed ports. Bipolar serrated graspers were placed in the left robotic hand, and monopolar electrosurgical scissors were placed in the right robotic hand. The tumor capsule was coagulated with the bipolar graspers and incised with the activated scissors. The tumor capsule was extremely thin and friable; however, the tumor was not soft enough to be removed with suction. In this fashion, an intracapsular tumor debulking was accomplished, with the resected tumor pieces removed by the laparoscopic graspers and suction operated by the urologic surgeon. After removing one third of the tumor, enough space was made to elevate the posterior aspect of the tumor revealing the tumor attachment to its nerve root of origin (Figure 5). The nerve was coagulated and transected, freeing the remaining, which was placed into an entrapment sack. A frozen section analysis confirmed the diagnosis of neurofibroma. Fibrin glue was placed over the nerve root to prevent leakage of cerebral spinal fluid.

Figure 5.

Retraction of tumor anteromedially after resection, showing tumor bed and nerve root.

A small pleurotomy occurred during the tumor resection; to evacuate the pneumothorax, a 10F Cope loop thoracostomy tube was placed percutaneously into the left hemithorax. The robot was used to close the pleurotomy with a running 4–0 chromic suture; the diaphragm was closed using silk suture and Lapra-Ty clips.

The total operative time was 5.3 hours, of which approximately 2 hours was robotic console time. The estimated blood loss was less than 50 mL. A postoperative chest x-ray in the postanesthesia care unit showed no pneumothorax. The chest tube was removed in the postanesthesia care unit, and repeat chest x-rays confirmed no pneumothorax had developed.

The patient was discharged home on postoperative day 2; there were no focal neurological deficits. While recovering in the hospital, the patient's pain was controlled with oral morphine CR (30 mg), given every 8 hours for a total of 7 doses. He was also given his usual dose of gabapentin (200 mg, 3 times a day). At discharge, the patient was given hydrocodone/acetaminophen (5/500) to be taken orally as needed every 4 hours for pain, and morphine CR (30 mg) to be taken orally as needed every 12 hours for pain for up to 1 week.

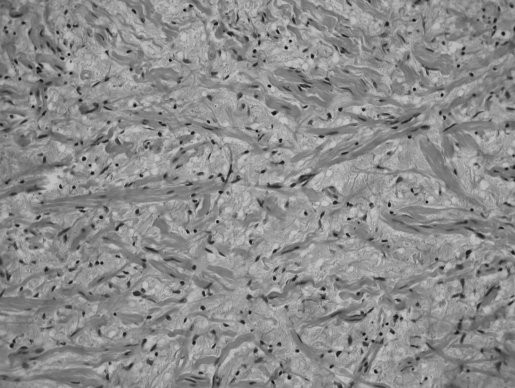

Pathological examination of the operative specimen showed it to be a neurofibroma, composed of stellate and spindle-shaped cells in a loose connective tissue matrix containing stout collagen fibers and rare entrapped axons (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Neurofibroma histology, showing the presence of stout collagen strands within the tumor. This has been referred to as a “shredded carrot” appearance.

At the patient's 1-week postoperative office visit, his pain had completely resolved. He was back to normal activity, and he had discontinued taking pain medications. No focal sensory or motor deficits were found on neurological examination, though the patient reported an area of numbness measuring 2 x 3 inches in his left thoracolumbar area.

DISCUSSION

Neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1), known as Von Recklinghausen disease, is an autosomal dominant disorder carried on chromosome 17. The incidence has been measured to be approximately 1 in every 3000 births.1 Besides the previously described identifying characteristics of NF-1 (neurofibromas, pigmented skin lesions, and Lisch nodules), it has the potential for multiple tumors (approximately 20% of NF patients)5 and the development of malignancies that have the greatest impact on quality and length of life.

Average length of life for patients with NF-1 has been determined by a retrospective chart review to be 54.1 years, compared with 70.1 years for the general population.1 Patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 were 1 time to 2 times more likely to have a malignant neoplasm at the time of death than the unaffected population; overall 2% to 16% of patients with neurofibromas develop neural sheath malignancies.1 Although there is no proven link between neurofibromatosis and melanoma, there have been almost 30 cases of melanoma reported in patients with neurofibromatosis.6 Optic gliomas develop in 15% of patients; however, only 2% to 5% are symptomatic.1

The drive to increase the precision of dissection has long been a focus of neurosurgical procedures and has been the impetus for microsurgical techniques.7 In this regard, robotic technology may prove to be an invaluable tool for applying minimally invasive techniques for tissue and nerve-sparing purposes.

The current da Vinci system supplies the surgeon with 4 robotic arms, one of which controls the high-definition, full color, 3-D magnified endoscope. The surgeon's movements are translated to the robotic arm movements without any noticeable delay and with up to 1:5 motion scaling; the robotic arms have 6 degrees of freedom. Also important, especially in the realm of neurosurgery, is the ability of the robot computer to automatically eliminate any surgeon hand tremor and provide the surgeon with a 540° wrist action.

In this young patient with a high risk of eventually requiring additional surgeries, we thought that a minimally invasive approach would be advantageous over an open procedure, as it would allow faster recovery and small incisions. Laparoscopic success of a retroperitoneal resection of a neurofibroma has already been reported in 3 separate cases; however, only one case was done with a pure laparoscopic approach, as was ours for the initial dissection, while the other 2 utilized a hand-assisted technique.2,3

The combination of the pure laparoscopic approach and the latest in robotic technology enabled us to complete the first successful robotic removal of a spinal tumor with minimal resulting morbidity, a brief hospital stay, and rapid postoperative recovery. We believe that the advent of robotic technology will prove to be a boon to the neurosurgeon. For the first time, the surgeon will be afforded an absolutely stable tremor-free working platform endowed with 6 degrees of freedom and a 540° wrist with up to 1:5 motion scaling. The last will afford the surgeon the ability to make the finest of movements in a highly controlled manner. Also, the endoscopic view with its 3D and high definition attributes provides an astounding image that can provide magnification in the 12X to 40X range. Lastly, and certainly not least, the ergonomic surgeon's console provides the surgeon with a seated working environment, free of gown, gloves, and mask, that provides a level of surgeon comfort, heretofore not possible.

CONCLUSION

Robotic-assisted laparoscopic resection of a retroperitoneal paraspinal neurofibroma was successfully completed for the first time. Further and more extensive applications of the da Vinci robot system within the field of neurosurgery await.

Contributor Information

Ross M. Moskowitz, Department of Urology, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, California, USA.; Department of Neurosurgery, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, California USA.

Jennifer L. Young, Department of Urology, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, California, USA..

Geoffrey N. Box, Department of Urology, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, California, USA..

Laura S. Paré, Department of Neurosurgery, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, California USA..

Ralph V. Clayman, Department of Urology, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, California, USA..

References:

- 1.Reynolds RM, Browning GG, Nawroz I, Campbell IW. Von Recklinghausen's neurofibromatosis: neurofibromatosis type I. Lancet. 2003;261:1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johna S, Shalita T, Johnson W. Laparoscopic-assisted resection of a large retroperitoneal tumor. JSLS. 2004;8:287–289 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawabata G, Mizuno Y, Okamoto Y, et al. Laparoscopic resection of retroperitoneal tumors: report of two cases. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1999;10:691–694 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan JA, Kohmoto T, Smith CR, Oz MC, Argenziano M. Endoscopic computer-enhanced mediastinal mass resection using robotic technology. The Heart Surgery Forum. 2003;6:E164–E166 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorensen SA, Mulvihill JJ, Nielsen A. Long-term follow-up of Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1010–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salvi PF, Lombardi A, Puzzovio A, et al. Cutaneous melanoma with neurofibromatosis type 1: rare association? A case report and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2004;75:91–95 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russel SM. Preserve the nerve: microsurgical resection of peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Oper Neurosurg. 2007;61:113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]