Abstract

Background:

Adrenal schwannomas are very rare tumors that are difficult to diagnose preoperatively. We report the case of a left adrenal schwannoma incidentally discovered in a 55-year-old man during a postoperative checkup for a cutaneous malignant melanoma.

Methods:

The biological evaluation was unremarkable, and the radiological examination revealed the adrenal mass that was first considered a metastatic lesion. Adrenalectomy was performed by the laparoscopic approach.

Results:

The postoperative course was uneventful. Histological examination established the correct diagnosis of schwannoma, which was also confirmed by immunohistochemical staining.

Conclusions:

A nonsecreting adrenal mass can be easily misjudged, especially in the context of a recently operated on malignancy. Unilateral adrenal metastasis needs pathological confirmation, as it can dramatically affect prognosis. Unusual tumors of the adrenal gland may be found incidentally, and a malignant context will generate difficulties in establishing the right management. Complete laparoscopic excision is the treatment of choice whenever feasible and will also clarify pathology.

Keywords: Adrenal gland tumor, Schwannoma, Laparoscopic adrenalectomy

INTRODUCTION

Schwannomas are rare tumors, usually benign, originating from the Schwann sheath of the peripheral or cranial nerves. Visceral schwannomas are extremely rare, and only a few cases of adrenal schwannomas have been reported. These usually present as incidental findings, nonsecreting adrenal masses in asymptomatic patients. A unilateral adrenal mass in a malignant context raises complex questions regarding its potential metastatic origin and the optimal therapeutic approach.

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old patient underwent a regular evaluation 2 months after removal of a Clark III level cutaneous malignant melanoma in the left scapular region. The patient was symptom-less, and the clinical examination was non-relevant.

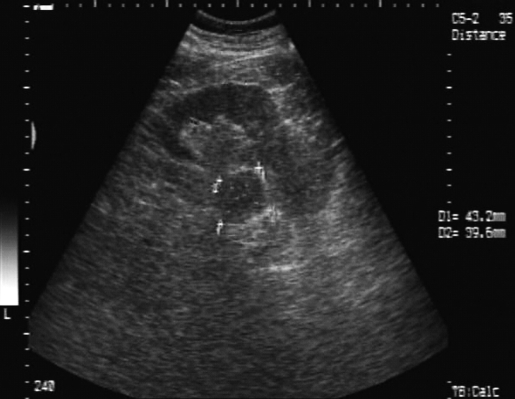

The abdominal ultrasound revealed an increased, nonhomogenous right adrenal gland 36/33 mm, and a left adrenal gland containing a hypo-echoic tumor 43/40 mm (Figure 1). The left adrenal tumor was confirmed on CT scan, and the tumor appeared to develop in the middle of the left adrenal gland. There were no other pathological findings, and MRI was not indicated for additional tumor characterization. The metabolic workup, including serum electrolytes, cortisol, urinary metanephrine, and vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) were within the normal range. At this stage, the lesion was highly suspicious for an isolated metastasis from the primary cutaneous malignant melanoma, while the rest of the workup was negative for metastatic melanoma.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound examination: hypoechoic mass 43/40 mm in the left adrenal gland.

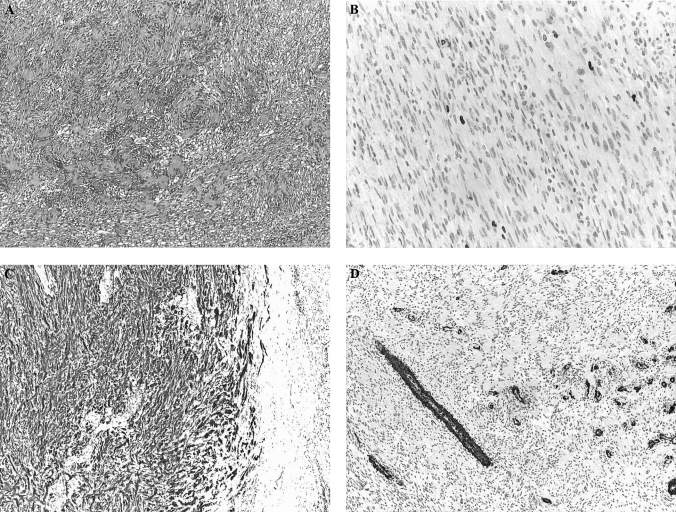

Although the tumor size was borderline, a left adrenalectomy was indicated, which was performed via a transperitoneal laparoscopic approach. The adrenal gland contained a hard well-circumscribed, encapsulated, 45/30/ 25-mm nodule. The pathological examination revealed a tumor consisting of a connective tissue proliferation, with fascicular architecture, with moderate cellular density, isolated nuclear palisades, and centers of hyalinization in the interstice. The immunohystochemical analysis demonstrated rare Ki67 positive cells (<1%), while S100 staining was positive diffusely across the tumor. SMA (smooth muscle actin) was negative in tumor cells, while positive in blood vessels (Figure 2). This aspect corresponds to a benign adrenal schwannoma type Antoni A.

Figure 2.

(A) Histopathological examination – hematoxilin eosine, 4×. Tumor mass consists of conjunctive proliferation, with fascicular architecture and isolated nuclear palisades. (B) Immunohistochemistry – KI67 staining, 20×. Rare positive cells (<1%). (C) Immunohistochemistry – S100 staining, 4×. Tumor cells are positive to this marker. (D) Immunohistochemistry – SMA staining, 4×. Tumor cells are negative, but blood vessels are diffusely positive.

The postoperative recovery was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the fifth postoperative day. Ultrasonic checkups at 6, 12, and 18 months showed no signs of recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Malignant melanoma is an extremely aggressive form of cancer. Adrenal metastases are found in 50% of cases of malignant melanoma and are most often clinically and biochemically silent.1 Imagistic characterization of these lesions is vague and cannot be used as a tool to differentiate them from a benign lesion.1,2 Fine-needle aspiration has been advocated as a diagnostic tool, but it requires expertise, is not always informative, and is associated with significant risk.3 Nevertheless, a solitary nonsecreting adrenal mass in a malignant context will certainly raise the question of a metastatic lesion and as such will alter prognosis and life expectancy. Attitudes toward removal of adrenal metastases are not clear, although some reports advocate laparoscopic removal. That will produce a debatable improvement in prognosis, while maintaining a very good safety profile.4–7 Probably, the major benefit will remain the removal of a specimen that can give a pathological confirmation of the metastatic disease. One should not neglect the remote possibility of a concomitant benign nonsecreting adrenal tumor and its psychological and legal implication for a subject initially assumed to have metastatic dissemination.

While incidentalomas are ever-more frequent due to improvements in imagistic diagnosis, there is a lot of debate regarding their possible surgical removal, more so in the laparoscopic environment. A typical workup should include serum electrolytes, low-dose dexamethasone suppression testing, and a 24-hour urine collection for catecholamines, metanephrines, vanyllilmandelic acid, and 17-ketosteroids. In general, functional tumors and nonfunctional tumors >4 cm in diameter should be removed by the laparoscopic approach. Heterogeneous tumors and enlarging tumors are considered for open surgery. FNAB should be performed only in patients with a history of carcinoma or suspected isolated metastasis. Smaller tumors can be followed closely with serial CT-scan or MRI, and a demonstrated growth should trigger surgical removal.8

Schwannomas are tumors originating from neural crest cells, and they contain differentiated Schwann cells in a stroma with little collagen. Their first description was done in 1908 by Verocay, and in 1920, they were subclassified by Antoni into 2 distinct histologic patterns.9 Schwannomas commonly originate in the myelin sheath of peripheral, motor, sensitive, sympathetic, or cranial nerves. They are most often found within the head, neck, upper and lower extremities, and with a lesser frequency on the trunk level, gastrointestinal tract, and retroperitoneum.

Usually they are benign, slow-growing, encapsulated tumors, but rarely may be malignant. Fabbro10 described a case of juxta-adrenal malignant schwannoma occurring in an 11-year-old boy. The malignant form is frequently associated with von Recklinghausen syndrome or other types of neurofibromatosis.11 Adrenal schwannomas are exceedingly rare; only 19 cases have been reported in the literature, most of them preoperatively diagnosed as non-secreting adrenal masses. Their origin appears to be in the Schwann cells of the nerve fibers innervating the adrenal medulla.12,13

While most adrenal schwannomas are incidental findings, sometimes patients experience minor clinical symptoms: abdominal pain, back pain,14 or hematuria.15 Goh16 described 7 patients with retroperitoneal schwannomas, 4 of which were thought to arise from the adrenal glands. The description of adrenal schwannomas in asymptomatic patients led to the hypothesis that the real frequency of this type of lesion is underestimated.17 Although Schwannomas are nonsecreting tumors, one case has been reported of a noradrenalin-secreting retroperitoneal schwannoma.18

CT-scan presentation is that of a well-circumscribed, homogeneous, round or oval mass, with slight enhancement.19 Cystic degeneration or calcification are described as a terminal stage of degeneration in a long-standing schwannoma and may suggest its diagnosis.20,21 MRI imaging findings are nonspecific,22 adrenal schwannomas being included in the differential diagnosis of solid nonfunctional adrenal tumors.23

Definitive diagnosis is possible only after histological examination of the operative specimen.24 Two distinct patterns have been described: Antoni A - cellular areas with nuclear palisades and Antoni B – with paucicellular areas.9 These 2 patterns may coexist in the same specimen but usually one is predominant. Immunohistological staining is essential for diagnosis, as tumor cells are positive for S-100 protein and vimentin. In some rare cases, positive staining with calretinin will exclude a possible S-100 positive neurofibroma.9,25

CONCLUSION

Retroperitoneal schwannomas are rare tumors that are difficult to diagnose. Preoperative workup is nondiagnostic and can only postulate a nonsecreting adrenal mass. Difficulties arise whenever we face an adrenal tumor in the context of a malignancy, when a hasty assumption of metastatic disease may have a major psychological impact and will change a patient's standard of care and quality of life. A nonsecreting adrenal mass >4 cm in diameter should be removed surgically with an added benefit of a definitive diagnosis. The laparoscopic approach should produce good results with minimal morbidity and rapid recovery.

Contributor Information

Eugen Târcoveanu, First Surgical Clinic, “St. Spiridon” Hospital, University of Medicine, Iaçsi, Romania..

Gabriel Dimofte, First Surgical Clinic, “St. Spiridon” Hospital, University of Medicine, Iaçsi, Romania..

Costel Bradea, First Surgical Clinic, “St. Spiridon” Hospital, University of Medicine, Iaçsi, Romania..

Radu Moldovanu, First Surgical Clinic, “St. Spiridon” Hospital, University of Medicine, Iaçsi, Romania..

Alin Vasilescu, First Surgical Clinic, “St. Spiridon” Hospital, University of Medicine, Iaçsi, Romania..

Raluca Anton, First Surgical Clinic, “St. Spiridon” Hospital, University of Medicine, Iaçsi, Romania..

Dan Ferariu, Department of Pathology, “St. Spiridon” Hospital, Iaçsi, Romania..

References:

- 1.Rajaratnam A, Waugh J. Adrenal metastases of malignant melanoma: characteristic computed tomography appearances. Australas Radiol. 2005;49(4):325–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potente G, Cantisani C, Cantisani V, et al. Valutazione con tomografia computerizzata delle metastasi da melanoma cutaneo. Radiol Med (Torino). 2001;101(4):275–280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quayle FJ, Spitler JA, Pierce RA, et al. Needle biopsy of incidentally discovered adrenal masses is rarely informative and potentially hazardous. Surgery. 2007;142(4):497–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlini M, Lonardo MT, Boschetto A, et al. Adrenal glands metastases from malignant melanoma. Laparoscopic bilateral adrenalectomy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2003;22(1):141–145 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saraiva P, Rodrigues H, Rodrigues P. Port site recurrence after laparoscopic adrenalectomy for metastatic melanoma. Int Braz J Urol. 2003;29(6):520–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sebag F, Calzolari F, Harding J, et al. Isolated adrenal metastasis: the role of laparoscopic surgery. World J Surg. 2006;30(5):888–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feliciotti F, Paganini AM, Guerrieri M, et al. Laparoscopic anterior adrenalectomy for the treatment of adrenal metastases. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13(5):328–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laal G, Clark OH. Endocrine surgery. In: Gardner DG, Shoback D. eds. Greenspan's Basic & Clinical Endocrinology. 8th ed McGraw-Hill Medical, New York, NY; 2007:926–927 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korets R, Berkenblit R, Ghavamian R. Incidentally discovered adrenal schwannoma. JSLS. 2007;11(1):113–115 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabbro MA, Costa L, D'Agostino S, et al. Juxta-adrenal malignant schwannoma. Pediatr Surg Int. 1997;12(7):532–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garcia G, Anfossi E, Prost J, et al. Benign retroperitoneal schwannoma: report of three cases. Prog Urol. 2002;12(3):450–453 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garg S, Mathew M, Goel T. Adrenal schwannoma: a case report and review of literature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2007;50(3):587–588 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kostakopoulos A, Pikramenos D, Livadas K, et al. Malignant schwannoma of the adrenals. A rare case. Acta Urol Belg. 1991;59(1):129–132 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma SK, Koleski FC, Husain AN, et al. Retroperitoneal schwannoma mimicking an adrenal lesion. World J Urol. 2002;20(4):232–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison KB, McAuley IW, Kinahan JF. Laparoscopic resection of a juxta-adrenal schwannoma. Can J Urol. 2004;11(3):2309–2311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF, et al. Retroperitoneal schwannoma. Am J Surg. 2006;192(1):14–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arena V, De Giorgio F, Drapeau CM, et al. Adrenal schwannoma: report of two cases. Folia Neuropathol. 2004;42(3):177–179 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takaki H, Kato T, Saito K, et al. Noradrenalin-secreting retroperitoneal schwannoma resected by hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery: report of a case. Surg Today. 2006;36(12):1108–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki K, Nakanishi A, Kurosaki Y, et al. Adrenal schwannoma: CT and MRI findings. Radiat Med. 2007;25(6):299–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikemoto I, Yumoto T, Yoshino Y, et al. Schwannoma with purely cystic form originating from the adrenal area: a case report. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2002;48(5):289–291 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrero Candau R, Ramirez Mendoza A, Morales Lopez A, et al. Benign adrenal schwannoma. Arch Esp Urol. 2002;55(7):858–860 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamamoto T. Retroperitoneal ancient schwannoma presenting as an adrenal incidentaloma: CT and MR findings. Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24(10):1389–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Behrend M, Kaaden S, Von Wasielewski R, et al. Benign retroperitoneal schwannoma mimicking an adrenal mass. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13(2):133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gazula S, Mammen JK. Schwannoma with concomitant tuberculosis in the adrenal gland. Indian J Urol. 2007;23:469–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hori T, Yamagiwa K, Yagi S, et al. Primary adrenal schwannoma. Nippon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;89(5):567–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]