Abstract

Many surgeons continue to actively pursue surgical approaches that are less invasive for their patients. This pursuit requires the surgeon to adapt to new instruments, techniques, technologies, knowledge bases, visual perspectives, and motor skills, among other changes. The premise of this paper is that surgeons adopting minimally invasive approaches are particularly obligated to maintain an accurate perception of their own competencies and learning needs in these areas (ie, self-efficacy). The psychological literature on the topic of self-efficacy is vast and provides valuable information that can help assure that an individual develops and maintains accurate self-efficacy beliefs. The current paper briefly summarizes the practical implications of psychological research on self-efficacy for minimally invasive surgery training. Specific approaches to training and the provision of feedback are described in relation to potential types of discrepancies that may exist between perceived and actual efficacy.

Keywords: Self-efficacy, Competence, Feedback, Surgical performance, Surgical technical skill

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, advances in the training of military and aviation personnel have been successfully applied to the training of health care providers in efforts to enhance patient safety. These include simulation to teach judgment and technical skills and a systems perspective in the analysis of errors and near misses. These methodologies help to sharpen the focus on important relationships between quality of care on the one hand and system issues, technical skills, communication, teamwork, and leadership on the other. They have also led to the systematic and standardized measurement of numerous processes and outcomes reflecting physician performance. Despite the success of many of these important efforts to support and assess physician performance, the individual surgeon continues to have a primary ongoing responsibility to accurately estimate and monitor his or her own capabilities, to identify training needs and to define those practices in which he or she can safely and effectively engage in at any given point in time.

The hasty adoption of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) during the late 1980s and early 1990s was accompanied by an enormous increase in surgical morbidity.1 Among the lessons learned from this chapter in surgical history is a greatly heightened awareness that the application of “cutting-edge” surgical practices must be preceded by an intense focus on training that closes the gap between the actual and perceived efficacy of the individual practitioner. However, closing the gap between an individual's actual and perceived efficacy is more complex than it may appear to be at first glance.

Cognitive psychologists and social learning theorists have been studying Self-Efficacy (SE) for several decades. SE is usually defined in the psychological literature as a person's estimate of his or her capacity to orchestrate performance on a specific task.2 The purpose of this paper is to briefly summarize the practical implications of psychological research on SE for minimally invasive surgery (MIS) training.

COMPONENTS OF SELF-EFFICACY

SE is conceptually composed of 3 components: level, strength, and generality.3 The level of SE refers to the difficulty of tasks that an individual believes he or she is capable of performing. While one MIS surgeon may feel he can perform LC on an obese, diabetic 65-year-old woman with 3 previous abdominal surgeries, an MIS surgeon with a lower level of SE may opt for an open approach or refer the patient to a more experienced surgeon.

The strength of SE refers to the confidence an individual has in his or her ability to attain a given level of performance. While one MIS surgeon may believe he or she can acquire the skills to safely perform a routine LC in less than 2 hours, a colleague with less SE strength may not believe that he or she can possibly attain such a level of proficiency and may not take advantage of training opportunities that could facilitate improvement.

The generality of SE refers to the generalization of efficacy beliefs from one activity to other activities either within the same domain or across a wide range of activities. For example, after performing 50 successful routine LCs, a surgeon with very high SE generality may believe he can safely perform LC on high-risk patients and perhaps even perform laparoscopic Nissen fundoplications without the need for much additional training. In contrast, a surgeon with a lower level of SE generality may seek much more additional training and mentoring before attempting LC on higher risk patients or moving on to other types of procedures.

ENHANCING SELF-EFFICACY

One important observation in the psychological research on SE is that an increase in positive beliefs or a reduction of debilitating beliefs often leads to higher task performance. However, the extent to which SE and performance can be improved varies considerably among individuals and situations. Individual differences in response to SE enhancement efforts are dependent on the extent of the perceived controllability of the SE determinants. If an individual perceives that neither the internal nor external determinants of efficacy are under his or her control or under the control of the organization within which he or she is working, then efforts to enhance SE are very likely to fail. In cases such as this, the individual with low SE often needs training in skills, such as assertiveness, influence tactics, impression management, leadership, or a combination of these.2

It is important to keep in mind that attributions about the causes of performance differ for people with high and low SE. Studies have shown that individuals with high SE who receive repeated negative performance feedback tend to increase effort more than individuals with low SE in the same situation. They also tend to exhibit less acceptance of negative feedback than individuals with low SE.4 Both high and low SE individuals tend to attribute success to the presence of ability. However, people with high SE tend to attribute failure to insufficient effort or bad luck (generally considered adaptive responses), while individuals with low SE tend to lay the blame on lack of ability.

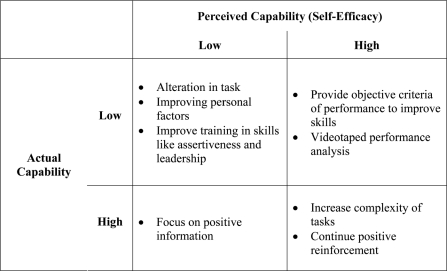

When attempting to enhance SE, consideration must be given to the accuracy of an individual's SE judgments as well as to the differences in the way performance feedback is processed by individuals possessing high SE versus those with low SE.5 Figure 1 delineates general guidelines for improving SE for individuals with varying levels of actual and perceived SE. For instance, the perceptual error, which results when an individual with low SE reports an inaccurately low assessment of true performance capability, may stem from incorrect assessments of task or individual influences on performance. In cases such as these, efforts to enhance SE should focus on provision of positive information (eg, verbal encouragement, reassurance about availability of help, resources, and other such things). When low SE represents an accurate assessment of low capability, SE should be increased indirectly through alterations in tasks (eg, beginning training at a lower skill level) and personal factors (eg, minimizing distractions) that are determined to relate directly to performance levels. It is important to appreciate that an intervention designed to enhance SE through training and the provision of task knowledge may increase SE and performance for some individuals but not others. Similarly, interventions aimed at increasing effort (eg, goal-setting and incentives) may increase SE and performance for some but not others.

Figure 1.

Methods for enhancing self-efficacy in individuals with varying degrees of perceived and actual ability.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS FOR MIS TRAINING

Stajkovic and Luthans6 conducted a metaanalysis of the research relating to SE and work-related performance. Their analysis of 114 studies concluded that SE is a significant determinant of performance and that efforts to improve SE may be more effective in improving performance than other common interventions (eg, those focused on goal-setting, feedback, or behavior modification). The 8 specific suggestions these authors describe for increasing both SE and performance are quite applicable to MIS training, as the examples we suggest indicate:

Provide clear, accurate, concise descriptions of tasks and task circumstances. For example, if trainees are given videotapes of procedures to review prior to performing the procedure, their performance may improve as well as their comprehension of the task.

-

Instruct trainees as to what technological means are necessary for successful performance and how to utilize those means.

For example, training in skills laboratories is invaluable in gaining understanding of technologies. Participation in skills laboratories can also improve performance and shorten operative time, thus saving resources.7 Research has shown that there can be an exponential increase in intraoperative performance dependent on time spent in a skills laboratory.7,8

Eliminate undesirable factors, such as distractions from the training environment. Ensuring that equipment checks are made prior to the case and trainees are shown and made comfortable with equipment prior to beginning the case will ease stress arising from unfamiliar technology. Because minimally invasive surgery is a team effort, it is important that the entire team is comfortable in both the procedure and also the equipment used.9 Distractions should be kept at a minimum and personal factors (ie, tiredness, hunger, illness) should be optimized to improve performance. Better and innovative design of the OR in minimally invasive surgery may also decrease the clutter and potential distractions.10

-

Implement programs designed specifically to enhance trainees' beliefs as to what they can do with the skills they already have.

Training approaches that emphasize what practicing surgeons can do with the skills they already have, how these skills can be applied to newer techniques or other procedures, and the limits of what they can do with the skills they have, can enhance both actual and perceived efficacy. Understanding of external cues and the role the trainers have to play may help in improving trainee performance. The role of self-fulfilling prophecies including the Pygmalion effect, Galatea effect, and Golem effect should be remembered when new skills are being taught. The Pygmalion effect is a special case of self-fulfilling prophecy whereby a person's (perceiver's) expectations of another (target) are transferred to, or otherwise have an influence on, the target such that the target ultimately modifies his or her behavior or achievement level in conformity with the expectations.11 Two factors that may influence the strength of the Pygmalion Effect are the amount of previous achievement and the initial self-expectancy level of the trainee. Persuasion can also be a powerful external environmental force influencing SE. A dramatic example of the effect of persuasion on SE is reported in Eden and Zuk's 1995 randomized study12 of Israeli naval cadets. Those cadets who had been told that they were unlikely to experience seasickness during a 5-day training mission performed better, experienced less seasickness, and reported greater SE at the end of training. The authors considered this study to be an example of the type of self-fulfilling prophecy termed the “Galatea Effect” in which high expectations conveyed through authoritative persuasion induces in such trainees the motivation to perform well.13 Enhancing SE in this manner has also been likened to a “verbal placebo” because the SE experienced by the experimental group appeared to quell their tendency toward seasickness. Frequently, underachievers can receive negative labels and thus become victims of the Golem effect–negative Pygmalion–whereby low expectations result in low performance. These self-fulfilling prophecies might affect a person in training and influence their ability to advance their skill levels. These principles are important and should be understood by those in leadership positions for surgeons in training. Studies have shown that setting specific goals and providing feedback stimulates trainees to improve their laparoscopic skills and tends to motivate students to practice more compared with a self-directed group.8

Provide training on how to develop effective behavioral and cognitive strategies for coping with complex tasks. This training should help individuals establish the conception of ability as an incremental skill. Many coping strategies have been described to help surgeons cope with operative stresses. They include early recognition of risks (ie, distractive thoughts, clouded judgment) and learning how best to stop and stand back to better analyze the situation. This may include avoiding over-focus on the task and breaking the vicious circle of anxiety and time pressure leading to clouded judgment and decision-making problems. Advanced techniques to obtain control of self include learning how to be physically relaxed, distancing techniques, and self-talk. Strategies to obtain better control of the situation include reassessment, decision-making, intraoperative planning and preparing, and better team communication and leadership. Training of these strategies early may help establish ability as an incremental skill.9

-

Time SE enhancement programs close in proximity to when task performance is expected.

Viewing videotaped procedures, familiarization with performance settings (eg, equipment, instruments, facilities, staff), and preparatory coaching sessions with a faculty surgeon are all examples of SE enhancement programs that should occur in close proximity to actual performance of procedures or trained tasks.

-

Provide clear and objective standards whereby individuals can gauge their level of performance accomplishment.

A recent study showed that surgeons consistently overestimated their performance during a laparoscopic colectomy course.14 Objective, standardized examinations of skills can alleviate this problem. Objective assessment of laparoscopic performance, using programs like the “Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery” (FLS) or “Virtual Reality” simulations would facilitate individuals in gauging their level of performance against clear and objective standards, thereby attaining an appropriate level of SE. FLS represents one of the first validated surgical education efforts to assess the competence of surgeons in a specific field.15 A recent report demonstrated that when residents were required to rate themselves in self-directed exercises and their rating was compared with that of attendings there was a high correlation (ie, residents who gave themselves a higher score tended to receive a higher score from faculty and vice versa). However, they tended to rate themselves lower than did faculty on almost all measures; even those residents with poor skills indicated that they were aware of their deficiencies.16 In another study, the use of videotapes of operations enabled multiple raters to assess operative performance reliably and shortened assessment times by 80%. This assessment technique shows potential as a means of evaluating the performance of advanced laparoscopic procedures by surgical trainees.17 Taken together, the results of these studies demonstrate that SE accuracy can vary across situations, levels of expertise of learners, and assessment methodologies further highlighting the importance of efforts to continually improve the objective measurement of performance in this arena.

Clarify the personal consequences attached to individual performance so that individuals perceive that outcomes are contingent on their performance and care about their performance.

For example, reviewing videotaped performances with trainees pointing out how their performance strengths and weaknesses contributed to the completion of training tasks or success of actual surgical procedures can improve trainees' perception of how outcomes are contingent on their performance.

CONCLUSION

The influence of SE on training outcomes and performance has been studied and demonstrated across a wide variety of settings. Its importance in the training and performance of MIS is apparent when one considers the rapid rate at which surgeons are continually expected to adapt to new technologies and the relative lack of formal standardized training and performance evaluation methodologies. Surgeons with inaccurate perceptions of their abilities may perform procedures they are not qualified to perform, refer cases to less qualified surgeons, choose to perform alternative procedures that may be associated with worse outcomes despite the fact that they may actually possess the ability to perform a preferable alternative procedure, or a combination of these.

The determinants of SE are multifactorial and involve both internal and external cues, some of which can be highly variable and difficult to control. Training outcomes and performance can be improved through specific efforts aimed at enhancing both the level and accuracy of SE.

References:

- 1.Morgenstern L, McGrath MF, Carroll BJ, Paz-Partlow M, Berci G. Continuing hazards of the learning curve in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1995;61:914–918 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982;37:122–147 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holladay CL, Quiñones MA. Practice variability and transfer of training: the role of self-efficacy generality. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(6):1094–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nease AA, Mudgett BO, Quiñones MA. Relationships among feedback sign, self-efficacy, and acceptance of performance feedback. J Appl Psychol. 1999;84(5):804–814 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gist ME, Mitchell TR. Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Academy of Management Review. 1992;17(2):183–211 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stajkovic AD, Luthans F. Self-efficacy and work-related performance: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 1998;124(2):240–261 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powers TW, Murayama KM, Toyama M, et al. Housestaff performance is improved by participation in a laparoscopic skills curriculum. Am J Surg. 2002;184:626–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonzalez R, Bowers SP, Smith CD, Ramshaw BJ. Does setting specific goals and providing feedback during training result in better acquisition of laparoscopic skills? Am Surg. 2004;70:35–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wetzel C, Kneebone R, Woloshynowych M, Nestel D, Moor-thy K, Kidd J, Darzi A. The effects of stress on surgical performance. Am J Surg. 2006;191(1):5–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alarcon A, Berguer R. A comparison of operating room crowding between open and laparoscopic operations. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:916–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNatt DB. Ancient Pygmalion joins contemporary management: a meta-analysis of the result. J Appl Psychol. 2000;85:314–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eden D, Zuk Y. Seasickness as a self-fulfilling prophecy: raising self-efficacy to boost performance at sea. J Appl Psychol. 1995;80(5):628–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eden D. Self-fulfilling prophecy as a management tool: harnessing Pygmalion. Academy of Management Review. 1984;9:64–73 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sidhu RS, Vikis E, Cheifetz R, Phang T. Self-assessment during a 2-day laparoscopic colectomy course: can surgeons judge how well they are learning new skills? Am J Surg. 2006;191:677–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swanstrom LL, Fried GM, Hoffman KI, Soper NJ. Beta test results of a new system assessing competence in laparoscopic surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:62–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandel LS, Goff BA, Lentz GM. Self-assessment of resident surgical skills: is it feasible? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1817–1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dath D, Regehr G, Birch D, et al. Toward reliable operative assessment: the reliability and feasibility of videotaped assessment of laparoscopic technical skills. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1800–1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]