Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery involves the introduction of instruments through a natural orifice into the peritoneal cavity to perform diagnostic and therapeutic surgical interventions. We report the utilization of the vaginal opening at the time of laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy or total laparoscopic hysterectomy as a natural orifice for appendectomy.

Methods:

We reviewed cases of 42 patients who underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy or laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy followed by appendectomy, performed by applying a stapler and removing the appendix transvaginally. By using a small-diameter laparoscope, the appendix was mobilized, especially in patients with adhesions, endometriosis, or retrocecal appendix, to facilitate transvaginal access with the stapler.

Results:

All procedures were performed successfully without intraoperative or major postoperative complications. The appendectomy portion of the procedure took approximately 5 minutes to 10 minutes. Appendiceal pathology included serosal adhesions (14), fibrous obliteration of the lumen (12), endometriosis (4), serositis (2), and carcinoid tumor (1), among others.

Conclusions:

Appendectomy performed with an endoscopic stapler introduced transvaginally for amputation and retrieval following total laparoscopic hysterectomy or laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy appears to be a safe and effective modification of established techniques with acceptable outcomes.

Keywords: Transvaginal appendectomy, Incidental appendectomy, laparoscopy, Hysterectomy, LAVH

INTRODUCTION

Minimally invasive surgery is defined as performing major operative procedures through smaller incisions. This results in less trauma and pain, faster recovery, and a better cosmetic outcome for the patient. With advancements in technology and developments in new and stronger light sources, smaller diameter scopes, and ancillary instruments like stapling devices, more procedures can be done through minimally invasive surgery. These new technologies have led us to an era of even less-invasive procedures. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) involves the introduction of instruments through a natural orifice into the peritoneal cavity to perform diagnostic and therapeutic surgical interventions.1,2 NOTES could result in smaller incisions and a subsequent reduction in postoperative pain, wound infection, adhesion formation, and nearly eliminate the risk of hernia formation. Although several reports have demonstrated the technical feasibility of per os transgastric and transcolonic approaches to certain procedures, current endoscopes and instruments are too flexible and insufficient to allow wide usage of this technology for procedures such as appendectomy. On the other hand, with enhancements in visualization provided by small scopes and the introduction of micro-instruments, increasing numbers of procedures could be done through 5-mm or smaller abdominal wall incisions assisted by the endoscopic technique. For now, the combination of a small-diameter scope and instruments with the natural orifice technique, such as transvaginal, may allow less-invasive procedures and favorable outcomes.

Appendectomy following a laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy has been done after removal of the uterus performed using standard laparotomy techniques from the vaginal approach.3 Building on this technique, vaginal removal of the appendix has been performed through a colpotomy incision made specifically for its removal through a trocar inserted in the posterior vaginal fornix.4,5 This report describes evolution through the aforementioned techniques. We present a modified method for appendectomy during total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) or laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) performed through the small-diameter laparoscope and a single-camera system utilizing the colpotomy incision for uterine removal, introduction of an endoscopic stapler, and subsequent appendiceal removal.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Forty-two patients underwent laparoscopic appendectomy at the time of total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) or laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) with concomitant appendectomies at a tertiary care center in Atlanta, Georgia. All patients signed informed surgical consent, Institutional Review Board approval of this report was obtained, and patient confidentiality has been maintained at all times. The mean patient age was 45.7 years (range, 32 to 63). Indications for hysterectomy are listed in Table 1. All patients underwent a routine preoperative mechanical and chemical bowel preparation and received one dose of prophylactic intravenous antibiotics immediately prior to the start of the procedure.6 Multipuncture operative laparoscopy was performed with the patient under general endotracheal anesthesia, as previously described.6 In most cases, umbilical and suprapubic 5-mm ports were used. When use of an operative laparoscope was necessary, a 10-mm umbilical port was used. Ancillary procedures are listed in Table 2. Endometriosis, adhesions, and other pelvic pathology were treated until anatomy was restored. Hysterectomy was completed as described previously.7

Table 1.

Indications for Surgery*

| Indication | Number |

|---|---|

| Pelvic pain | 41 |

| Abnormal uterine bleeding | 24 |

| Endometriosis | 17 |

| Persistent adnexal mass | 6 |

| Symptomatic leiomyomata | 6 |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 4 |

| Symptomatic pelvic relaxation | 2 |

| Endometrial cancer | 1 |

Most patients had more than one indication.

Table 2.

Ancillary Procedures

| Procedure | Number |

|---|---|

| Cystoscopy | 42 |

| Lysis of adhesions | 41 |

| Treatment of endometriosis | 33 |

| Adnexectomy | 37 |

| Culdoplasty | 26 |

| Enterolysis | 26 |

| Ureterolysis | 15 |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 9 |

| Cholecystectomy | 4 |

| Ureteral catheterization | 2 |

| Ureteroneocystostomy | 1 |

| Ovarian cystectomy | 1 |

| Anterior/posterior colporrhaphy | 1 |

| Rectosigmoid lesion excision | 1 |

| Burch procedure | 1 |

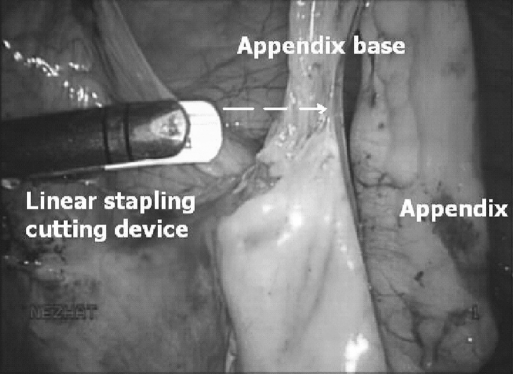

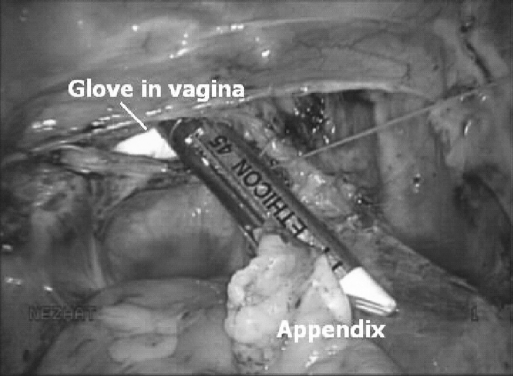

Appendectomy was performed following vaginal removal of the uterus during TLH or after a laparoscopic colpotomy incision was made during LAVH, for larger uteri, prior to morcellation and removal of the uterus vaginally. A sterile glove containing two 4x4-cm sponges was placed in the vagina to maintain pneumoperitoneum.8 Using 3-mm or 5-mm conventional coagulating and cutting instruments, mostly bipolar forceps and scissors or ultrasonic shears, the mesoappendix was electrodesiccated and cut until the appendix was mobilized to its base. In cases of retrocecal appendix, retroperitoneal structures were identified and attachments of the bowel and mesoappendix were freed. An endoscopic 2.5-mm stapler, the ETS Compact Flex 45 Articulating Linear Cutter (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH) or the ENDO GIA (US Surgical, Norwalk, CT) was introduced into the pelvic cavity via the colpotomy incision and over the vaginal glove. The stapler was placed across the appendiceal base, and amputation of the appendix was performed with one application (Figure 1). The appendix was then removed via the colpotomy incision, with or without the use of an endoscopic bag (Figure 2). Following appendiceal removal, copious irrigation of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, and the vaginal cuff was closed in routine fashion for TLH, with laparoscopic suturing with 0 Vicryl interrupted and extracorporeal knot tying.7 If uterine morcellation was done vaginally and the cuff was easily accessible, closure was done vaginally with 0 Vicryl figure of eight sutures.

Figure 1.

A linear stapling cutter is introduced through the posterior colpotomy to amputate the appendix.

Figure 2.

The glove maintains pneumoperitoneum as the stapler and specimen are removed through the colpotomy.

RESULTS

All intended surgical procedures were carried out successfully. The procedure time of the appendectomy was approximately 5 minutes to 10 minutes. No intraoperative complications or major postoperative complications occurred. Forty of 42 patients were started on a clear liquid diet on postoperative day one and advanced to a low-residue diet within 48 hours without difficulty. One patient was started on a clear liquid diet on postoperative day 2 without complication. Another patient, who had a long history of abdominal pain, endometriosis, adhesions, and a gallbladder polyp, developed postoperative ileus that resolved with bowel rest. In addition to hysterectomy and appendectomy, the patient underwent extensive enterolysis, left ureterolysis, treatment of pelvic fibrosis and endometriosis, right salpingo-oophorectomy, culdoplasty, cystoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and cholecystectomy. Intraoperatively, the mesoappendix was thickened, congested, and adhered to the pelvic brim, but the appendectomy was completed in the intended fashion. The patient tolerated a clear liquid diet by postoperative day 4. One patient had a temperature of 101.8° Fahrenheit on postoperative day one without any obvious source of infection. This was presumed to be due to atelectasis and resolved with pulmonary toilet.

The mean postoperative stay was 1.5 days with 24 patients discharged home on the first postoperative day, 15 on the second, 1 on the third day, and 2 on the fourth. Pathological studies of 30 appendectomy specimens revealed mostly serosal adhesions (14) and fibrous obliteration of the lumen (12) (Table 3). Twelve specimens showed no significant abnormal pathology, and several specimens had more than one pathology.

Table 3.

Pathology Results

| Pathology | Number* |

|---|---|

| Serosal Adhesion | 14 |

| Fibrous obliteration of the lumen | 12 |

| Endometriosis | 4 |

| Serositis | 2 |

| Intramucosal inflammation | 1 |

| Mesothelial lines cyst | 1 |

| Fibrosis | 1 |

| Mucocele | 1 |

| Carcinoid tumor | 1 |

Some specimens had more than one pathology, and 12 specimens had no significant pathology.

Patients were seen for follow-up visits during postoperative weeks 1 and 6. Minor outpatient postoperative complications were as follows: 3 urinary tract infections (UTI) successfully treated with oral antibiotics, 1 umbilical incision cellulitis treated with oral dicloxacillin, and 1 vaginal cuff granulation tissue repair 3 months after the hysterectomy. There were no other febrile episodes and no cases of vaginal cuff infection.

DISCUSSION

The lifetime risk of developing acute appendicitis is 7%.9 The incidence of appendicitis causing abdominal pain depends on the clinical setting. In series from emergency departments or surgical services, 25% of patients under age 60 who are evaluated for acute abdominal pain have appendicitis.1 The morbidity and mortality from appendicitis remains significant even with the advent of antibiotics and surgical management. Although the overall mortality rate of treated appendicitis is less than 1%, in the elderly it remains approximately 5% to 15%.1,2,10 The incidence of perforation in patients with appendicitis ranges from 17% to 40% with a median of 20%.11,12 The perforation rate is significantly higher in the elderly, with rates as high as 60% to 70%.13 The negative laparotomy rate in patients with abdominal pain ranges from 15% to 35% and is also associated with significant morbidity. The negative laparotomy rate is significantly higher in young woman (up to 45%).14,15

Incidental appendectomy has become a commonly practiced procedure, and since the first description of laparoscopic appendectomy in 1983 by the late Professor Kurt Semm,16 surgeons continue to search for innovations to improve efficiency and technique. Although there is concern about increased morbidity associated with incidental appendectomy during lymphadenectomy, there are many reports of its safety.17,18 The ACOG Committee Opinion states that in patients with a history of endometriosis or undergoing evaluation for chronic pelvic pain, incidental appendectomy may demonstrate a clear benefit.19 Albright et al20 reported a benefit in cost for women undergoing incidental appendectomy during laparotomy of $7,776 per 10,000 population in the age group of 0 years to 5 years and $1,092 per 10,000 population in the 40 to 49 age group. Ideally, incidental appendectomy does not require the introduction of new instrument systems, but simply modifies the utilization of available equipment.

Originally, vaginal appendectomy was only possible when the appendix was easily accessible during total vaginal hysterectomy.21 In earlier years during LAVH, the appendix was mobilized laparoscopically, but amputated and removed vaginally by standard laparotomy techniques.3 Minimally invasive surgery and new instrumentation has allowed for the incidental appendectomy to develop from a vaginal approach, mainly through laparoscopic colpotomy incisions. The performance of a posterior colpotomy during laparoscopy has been described for removal of the gallbladder, kidney, spleen, resected portions of colon, and pelvic masses.22–26 Ghezzi et al4 described appendectomy utilizing endoloops through abdominal 5-mm trocars and a posterior colpotomy for retrieval with an endoscopic bag. In 2007, Tsin et al5 utilized 3-mm to 5-mm abdominal trocars and introduced a 12-mm ETS endoscopic linear cutter (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH) through the posterior cul-de-sac in a varied appendectomy method. The appendix was removed via an endoscopic bag also introduced through the vaginal trocar. A variation of this vaginal appendectomy was developed for cases where hysterectomy was not performed, utilizing a posterior culdotomy or colpotomy.

This report presents a modified technique for transvaginal appendectomy during TLH or LAVH utilizing small ports, thereby obviating the need for additional incisions, 12-mm trocars, or additional camera systems. With advances in camera systems, powerful light sources and 3-mm to 5-mm scopes, most operative laparoscopy procedures can be done successfully through 5-mm or smaller ports. Smaller incisions have the obvious benefits of less pain and lower chances of herniation and, of course, being more cosmetic. With microlaparoscopy, detachment of the appendix can be done but a larger incision is necessary to remove the appendix from the abdomen. Use of a stapler transvaginally speeds up the appendix detachment and extraction through the vaginal cuff opening as part of the hysterectomy.

Overall, upon review of our 42 cases, this technique of appendectomy did not interfere with other procedures, add significant procedure time, or cause intraoperative or major postoperative complications. This method of appendectomy during laparoscopic hysterectomy utilizing a vaginally introduced and retrieved endoscopic stapler encompasses the potential conveniences of the previously described procedures.3–5 The surgeon has less difficulty obtaining adequate exposure of the appendix laparoscopically and does not need expertise in vaginal surgery. The only additional instrument used is an endoscopic stapler-cutting device, which has been found to be safe for laparoscopic appendectomy.19 As NOTES evolves with improvement in instrumentation, other techniques could be established following these fundamentals.

CONCLUSION

Appendectomy performed with an endoscopic stapler introduced via a posterior colpotomy for amputation and retrieval following TLH or LAVH appears to be a safe and effective modification of established techniques with acceptable outcomes.

Contributor Information

Ceana Nezhat, Atlanta Center for Special Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA..

M. Shoma Datta, Baltimore, Maryland, USA..

Andrew DeFazio, Atlanta Center for Special Minimally Invasive Surgery and Reproductive Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA..

Farr Nezhat, New York, New York, USA..

Camran Nezhat, Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, USA..

References:

- 1.Balsano N, Cayten CG. Surgical emergencies of the abdomen. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1990;8:399–410 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bugliosi TF, Meloy TD, Vukov LF. Acute abdominal pain in the elderly. Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:1383–1386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pelosi MA, 3rd, Pelosi MA. Vaginal appendectomy at laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: a surgical option. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1996;6:399–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghezzi F, Raio L, Mueller MD, Franchi M. Laparoscopic appendectomy: a gynecological approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;12:257–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsin DA, Colombero LT, Lambeck J, Manolas P. Minilaparoscopy-assisted natural orifice surgery. JSLS. 2007;11:24–29 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nezhat C, Nezhat CH, Nezhat F, Ferland R. Laparoscopic access: principles of laparoscopy. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat CH, eds. Nezhat's Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy, 3rd ed Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008; 40 56 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nezhat F, Yadav J. Hysterectomy: laparoscopy and hysterectomy. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat CH, eds. Nezhat's Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy, 3rd ed Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008;341–362 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ocampo J, Nutis M, Nezhat C, Nezhat CH, Nezhat F. Equipment. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat CH, eds. Nezhat's Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy, 3rd ed Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008;9–34 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irvin TT. Abdominal pain: a surgical audit of 1190 emergency admissions. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1121–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenyo G. Acute abdominal disease in the elderly. Am J Surg. 1982;143:751–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gamal R, Moore TC. Appendicitis in children aged 13 years and younger. Am J Surg. 1990;159:589–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Putnam TC, Gagliano N, Emmens RW. Appendicitis in children. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:527–532 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner JM, McKinney WP, Carpenter JL. Does this patient have appendicitis? JAMA. 1996;276:1589–1594 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:910–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bongard F, Landers DV, Lewis F. Differential diagnosis of appendicitis and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Surg. 1985;150:90–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albright JB, Fakhre GP, Nields WW, Metzger PP. Incidental appendectomy: 18-year pathologic survey and cost effectiveness in the nonmanaged-care setting. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:298–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovac SR. Vaginal hysterectomy. Baillieres Clin Ostet Gynaecol. 1997;11:95–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart EA, Liau AS, Friedman AJ. Operative laparoscopy followed by colpotomy for resecting a colonic leiomyosarcoma. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1991;36:883–887 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elective coincidental appendectomy ACOG Committee Opinion No. 323. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1141–1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emmermann A, Zornig C, Peiper M, Weh HJ, Broelsch CE. Laparoscopic splenectomy. Technique and results in a series of 27 cases. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:924–927 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breda G, Silvester P, Giunta A, Xausa D, Tamai A, Gherardi L. Laparoscopic nephrectomy with vaginal delivery of the intact kidney. Eur Urol. 1993;24:116–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delvaux G, Devroey P, De Waele, Willems G. Transvaginal removal of gallbladders with large stones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1993;3:307–309 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghezzi F, Raio L, Muller MD, Gyr T, Buttarelli M, Franchi M. Vaginal extraction of pelvic masses following operative laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1691–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner M, Aronsky D, Tschudi J, Metzger A, Klaiber C. Laparoscopic stapler appendectomy: A prospective study of 267 consecutive cases. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:895–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Semm K. Endoscopic appendectomy. Endoscopy. 1983;15:59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leibovitch I, Rowland RG, Goldwasser B, Donohue JP. Incidental appendectomy during urological surgery. J Urol. 1995;154:1110–1112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]