Abstract

Acute postoperative anastomotic complications following colorectal resection include leak and obstruction. Often an operation is necessary to treat these complications. The role of endoluminal procedures to treat these complications has been limited. This article illustrates that such an approach is technically feasible and can be used to treat some colorectal anastomotic complications.

Keywords: Anastomotic complications, Endoscopic management, Stent

INTRODUCTION

Advances in endoscopy over the last decade have provided the endoscopic surgeon an armamentarium of tools that have shifted the field from a purely diagnostic modality to a therapeutic one. One illustration of this progress is endoscopic decompression of malignant colorectal obstruction with self-expanding stents, a procedure that has gained wide acceptance as an alternative to surgical diversion or excision, especially in the setting of metastatic disease or in poor surgical candidates.1–7 Stenting of benign colorectal conditions has been described, but its role has been limited due to technical issues and lack of long-term data on permanent metal stents for nonmalignant disease.8–13 However, with the recent introduction of nonmetal esophageal stents, there is a growing interest and some experience with their role in the treatment of benign conditions, including postoperative complications following esophageal or gastric surgery.14–16

In this article, I describe the technical aspects and results of endoscopic stenting in 2 patients with acute postoperative anastomotic complications following colorectal surgery.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient 1

A 52-year-old man underwent an elective left hemicolectomy for a 2-cm adenoma. He was discharged home on the third postoperative day but readmitted to the hospital a week later with abdominal distention, nausea, and vomiting. A computed tomography of the abdomen at the time of admission revealed colonic obstruction at the anastomosis with surrounding inflammatory changes without evidence of intraabdominal abscess (Figure 1). He was managed with nasogastric tube decompression, bowel rest, and intravenous peripheral nutrition. The bowel obstruction persisted, and an operation was advised, but the patient inquired about alternative options. The colorectal surgery service was consulted. At the time of consultation, the patient's vital signs were stable and he was afebrile. His abdomen was significantly distended without peritoneal signs. His laboratory findings included a normal white count. Gastrograffin enema demonstrated complete anastomotic obstruction without a leak. On postoperative day 15, the patient consented to endoscopic stenting with possible laparotomy, colonic resection, and fecal diversion.

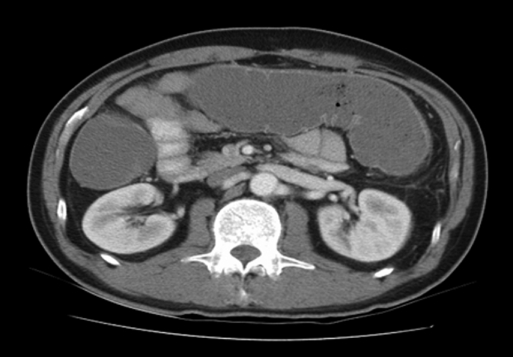

Figure 1.

Computed tomography of patient #1 demonstrates colonic obstruction.

Patient 2

A 67-year-old woman presented with massive lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage secondary to diverticulosis. The bleeding persisted, and following transfusion of 8 units of packed red blood cells, the patient underwent emergent abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis. Her postoperative course was significant for persistent bowel obstruction managed with bowel rest, nasogastric tube decompression, intravenous antibiotics, and fluids. Computed tomography performed on postoperative day 10 revealed an anastomotic obstruction with a leak, perianastomotic inflammatory changes, and free air under the diaphgram. The colorectal surgery service was consulted. At the time of evaluation, the patient was ill-appearing and debilitated. Her vital signs showed sinus tachycardia with a heart rate of 115 beats per minute, and a temperature of 38.5 degrees Celsius. Her abdomen was significantly distended, and she had localized peritoneal signs in the lower quadrants. Her laboratory findings included a white blood count 12.1 × 103/µL, hemoglobin 8.9 g/dL, and albumin of 1.8 g/dL.The patient was advised to undergo laparotomy with diverting ileostomy, but her family inquired about alternative options with the hope of avoiding a stoma. Endoscopic intervention was discussed, and the patient consented to endoscopic stenting with possible laparotomy and fecal diversion.

ENDOSCOPIC TECHNIQUE AND RESULTS

The procedures were performed in the endoscopy suite with the patient under intravenous sedation. The patients were placed in the left lateral decubitus position. The flexible sigmoidoscope was advanced to the anastomosis. An edematous and obstructed anastomosis was noted in patient 1 at 60 cm from the anal verge (Figure 2). In patient 2, there was dehiscence of approximately 40% of the anastomosis with an associated abscess cavity (Figure 3). Under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance, the anastomosis was carefully traversed in both patients by using an Amplatz Super Stiff wire (0.09652 cm × 260 cm) (Boston Scientific, Natick, Maryland). A stiff wire was used to support the rigid stent delivery device. The endoscope was withdrawn keeping the wire in place, and the delivery device of the Polyflex stent (120 mm, 18x23 mm diameter) (Boston Scientific, Natick, Maryland) was advanced over the wire under fluoroscopic and endoscopic guidance. In patient 1, the adult flexible sigmoidoscope was used to straighten the sigmoid loop to allow safe advancement of the rigid delivery device. The stent was centered across the anastomosis, and the position was verified by fluoroscopy with the flexible endoscope tip at the distal aspect of the stent. The stent was successfully deployed in both patients, and the delivery device and endoscope were withdrawn without difficulty (Figure 4).

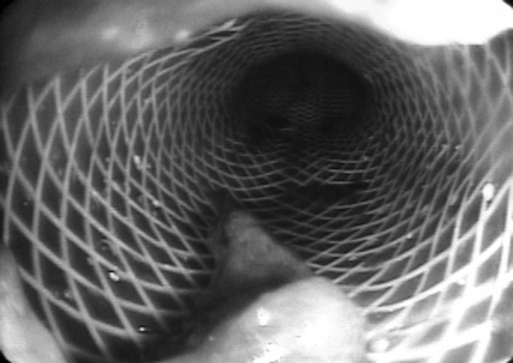

Figure 2.

Endoscopic appearance of anastomotic obstruction in patient #1.

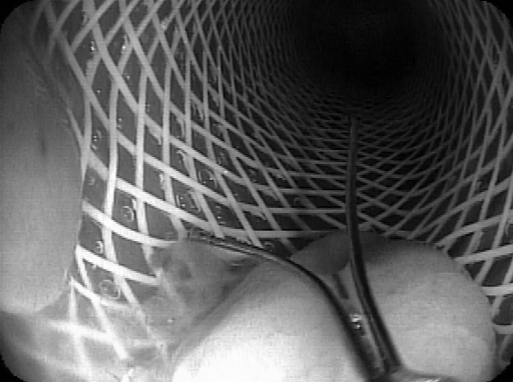

Figure 3.

Endoscopic appearance of anastomotic leak with cavity in patient #2 (dehiscence on left, the bowel lumen with wire on the right).

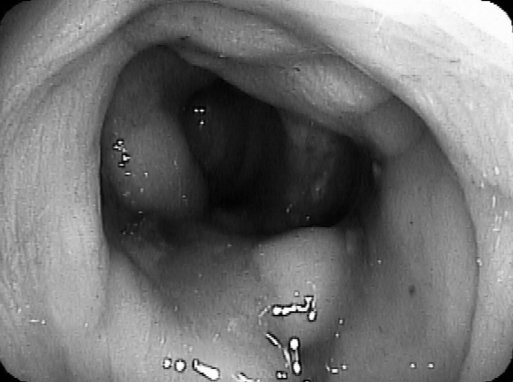

Figure 4.

Luminal view after stent deployment in patient #1.

Patient 1 had spontaneous decompression of his colonic obstruction with passage of flatus and bowel movement the day of the procedure. The nasogastric tube was removed, and a liquid diet was initiated the following day. Seventy-two hours later, there was spontaneous passage of the stent. The patient was discharged home on post operative day 19. Repeat colonoscopy 8 months later revealed a patent, nonstrictured anastomosis (Figure 5). The patient remains well 22 months following his procedure.

Figure 5.

Anastomosis in patient #1 at 8 months.

Patient 2 had spontaneous decompression of her obstruction the day of her procedure but 2 days later redeveloped obstructive symptoms. Repeat endoscopy revealed migration of the stent into the distal rectum. Repeat stenting was performed, and the distal aspect of the new stent was clipped to the rectal mucosa by using 4 Resolution clips (Boston Scientific, Natick, Maryland) to minimize migration. The patient's condition improved, and she was started on a liquid diet; however, 10 days following her second stent, her symptoms recurred. Repeat endoscopy showed migration of the stent. Stenting was repeated, and the distal aspect of the stent was secured to the rectum by using TriClip clips (Wilson-Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, North Carolina) (Figure 6). The obstructive symptoms resolved, and the patient was started on a liquid diet that was advanced to a regular diet. She was discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 28. Except for a urinary tract infection treated on an outpatient basis, she had a full recovery. One month after discharge, the Polyflex stent was removed in the endoscopy suite. Repeat endoscopy 3 months later demonstrated a patent and healed anastomosis without evidence of stricture (Figure 7). She remains well and free of obstructive symptoms 6 months following her hospitalization.

Figure 6.

Polyflex stent with Triclip clip fixation in patient #2.

Figure 7.

Endoscopic view of healed and patent ileorectal anastomosis 3 months poststenting in patient #2.

DISCUSSION

Although uncommon, acute anastomotic complications following colorectal resection do occur and are distressing to the patient and the surgeon. They include bleeding, obstruction, or leakage that often results in reoperative surgery in the early postoperative period. Reoperative intervention in such a setting carries increased morbidity, prolonged recovery, and may lead to fecal diversion, committing the patient to additional operations to close the stoma.

Endoscopic stenting can effectively palliate malignant colorectal obstruction in patients with metastatic disease or in patients who are poor surgical candidates due to significant medical comorbidities.1–7 However, stenting for benign colorectal disorders has not been widely practiced or advocated due to technical limitations, lack of instrumentation, and absence of long-term data on its effectiveness and the safety of metal stents.7–13 Furthermore, numerous operative interventions are available to successfully address the needs of most patients with benign colorectal disorders. But with the recent introduction of covered metal and nonmetal esophageal stents, there has been interest in exploring their role in the management of benign gastrointestinal conditions or postoperative complications following gastric or esophageal surgery.14–16 Eubanks and colleagues14 recently reported their experience with off-label use of polyester or silicone covered esophageal stents in 19 patients with gastrojejunal anastomotic complications following bariatric surgery. The stenting was undertaken for acute leaks in 11 patients, chronic gastrocutaneous fistulas in 2, and stricture in 6.

Immediate symptomatic improvement was noted in 90% of their patients, including 91% of the patients with leaks and 84% of patients with strictures. During a mean follow-up of 3.6 months, resolution of the anastomotic complications was noted in 16 patients (84%). A total of 34 stents were used in the 19 patients with an endoscopic reintervention rate of 42%. The most common complication was stent migration, which occurred in 58% of stent placement. While most patients with stent migration were treated endoscopically, 3 required laparoscopic extraction of the stent from the distal small intestine. In another study from Germany, Kauer and colleagues15 reported their stenting experience with thoracic anastomotic leaks after esophagectomy. Ten consecutive patients underwent placement of a covered metal stent. Successful leak occlusion was noted in 90% of the patients. Stent migration occurred in 40% of patients. Endoscopic reintervention to treat stent-related complications was performed in 50% of patients. No patient required surgical intervention. During the study period, 5 patients underwent endoscopic stent removal after full healing, 3 had spontanenous passage of the stent per anus, and 2 patients died with the stent in place from nonstent related causes. A recent study from Karbowski and colleagues in Seattle reported their experience with the Polyflex esophageal stent in a variety of esophageal conditions. The Polyflex stent is a self-expanding and removable stent composed of a polyester infrastructure with silicone covering. Currently, it is approved in the United States for esophageal insertion. In their study, a total of 37 stents were placed in 30 patients with esophageal conditions. Twenty patients (66%) had benign conditions. Indications for stenting included esophageal fistula in 7, anastomotic stricture in 5, acute esophageal perforations in 3, acute postoperative leak in 1, and other causes in 14. Technical success was 100%, but stent migration was noted in 30% of patients.

Endoscopic stenting for malignant colorectal disease is an option for patients with metastatic disease or those who are poor surgical candidates.1–7 However, little data exist on its role in benign conditions.8–13 The 2 patients described in this report illustrate that endoscopic stenting can be helpful in patients with acute postoperative complications after colorectal resection. While the standard of care in 2009 is operative procedure when an intervention is needed under such circumstance, an endoscopic approach may successfully treat the anastomotic complication and avoid the morbidity and recovery of another laparotomy and the potential need for fecal diversion. However, it is important to note that there is a lack of data in the literature on the short- and long-term outcome of the interventions described in this report. Furthermore, the Polyflex stent is FDA approved for esophageal indications and was used off-label in this study due to the lack of other commercially available stents to treat benign colorectal conditions. However, the patients' request to seek an alternative to operative intervention and possible stoma raised the possibility of an endoscopic option. But only after assessing the patients' full understanding that endoscopic stenting for their conditions is experimental at this stage and after obtaining full informed consent was the procedure undertaken. Fortunately, this nonconventional approach resolved the anastomotic complications in both patients but also demonstrated the challenges noted by the above studies in terms of risk of migration and the need for multiple endoscopic reinterventions. The risk of stent migration and need for reintervention in the setting of benign disease is higher than when stents are used for malignant obstruction.9,14–16 In the case of the second patient, the use of a TriClip (Wilson-Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, North Carolina) clip to secure the distal end of the stent to the bowel wall helped prevent further migration. The use of TriClip in this setting was off-label, and there is currently no data in the literature to support such a use. To my knowledge, currently no other means area available to properly anchor a temporary stent to the bowel. Future technologic development may yield stent devices that are less prone to migration or ancillary fixation clips that help fixation to the colorectal wall.

CONCLUSION

Some postoperative anastomotic complications, traditionally managed operatively, may be amenable to endoscopic interventions, as illustrated by the 2 cases in this report. Hopefully, future technological advances will increase the armamentarium of tools and enable endoscopic surgeons to tackle a broader spectrum of colorectal conditions with endoluminal procedures.

References:

- 1.Spinelli P, Mancini A. Use of self-expanding metal stents for palliation of rectosigmoid cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:203–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron TH, Dean PH, Yates MR, et al. Expandable metal stents for the treatment of colonic obstruction: techniques and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47(3):277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turegano-Fuentes F, Echenagusia-Belda A, Simo-Muerza G, et al. Transanal self-expanding metal stents as an alternative to palliative colostomy in selected patients with malignant obstruction of the left colon. Br J Surg. 1998;85:232–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lobato RF, Pinto I, Paul L, et al. Self-expanding prostheses as a palliative method in treating advanced colorectal cancer. Int Surg. 1999;84:159–162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law WL, Choi HK, Lee YM, et al. Palliation for advanced malignant colorectal obstruction by self-expanding metallic stents: prospective evaluation of outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(1):39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meisner S, Hensler M, Knop FK, et al. Self-expanding metal stents for colonic obstruction: experiences from 104 procedures in a single center. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:444–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki N, Saunders BP, Thomas-Gibson S, Akle C, Marshall M, Halligan S. Colorectal stenting for malignant and benign disease: outcomes in colorectal stenting. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1201–12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baron TH, Yates MR. Treatment of a radiation-induced sigmoid stricture with an expandable metal stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50(3):422–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forshaw MJ. Self-expanding metallic stents in the treatment of benign colorectal disease: indications and outcomes. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8(2):102–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laasch HU. Treatment of colovaginal fistula with coaxial placement of covered and uncovered stents. Endoscopy. 2003;35(12):1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeyarajah AR, Shepherd JH, Fairclough PD, Patchett SE. Effective palliation of a colovaginal fistula using a self-expanding metal stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46(4):367–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbas MA, Falls G. Endoscopic stenting of colovaginal fistula: the transanal and transvaginal “kissing” wire technique. JSLS. 2008;12(1):88–92 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Small AJ, Young-Fadok TM, Baron TH. .Expandable metal stent placement for benign colorectal obstruction: outcomes for 23 cases. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:454–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eubanks S, Edwards CA, Fearing NM, et al. Use of endoscopic stents to treat anastomotic complications after bariatric surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(5):935–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kauer WKH, Stein HJ, Dittler HJ, Siewert JR. Stent implantation as a treatment option in patients with thoracic anastomotic leaks after esophagectomy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:50–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karbowski M, Schembre D, Kozarek R, Ayub K, Low D. Polyflex self-expanding, removable plastic stents: assessment of treatment efficacy and safety in a variety of benign and malignant conditions of the esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1326–1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]