Abstract

Background:

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS) is a rare condition causing acute or chronic compression of the third part of the duodenum, due to a reduction in the aortomesenteric angle. Traditionally, an open duodenojejunostomy is recommended when conservative management fails. Laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy is a minimally invasive option that has been reported in up to 10 cases. We describe our operative technique in one case and review the literature on this condition.

Methods:

A previously well 66-year-old man presented with acute gastric dilatation. An abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan and oral Gastrografin meal revealed a dilated stomach and proximal duodenum due to compression of the third part of the duodenum between the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and aorta.

Results:

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) ruled out intraluminal causes. A laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy was performed when conservative management failed. Postoperative recovery was quick and uneventful. Gastrografin administration on the fifth day showed no leak, with free flow of contrast into the jejunum. The patient resumed a normal diet and remained asymptomatic at 6-month follow-up.

Conclusion:

Laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy is feasible, safe, and effective. It gives the same results as open surgery with all the advantages of minimally invasive surgery.

Keywords: Laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy, Superior mesenteric artery syndrome, Acute gastric dilatation

INTRODUCTION

Superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS), also known as Wilkie's syndrome,1 is a very rare cause of proximal small-bowel obstruction that was first described by Rokitansky in 1861.2,3 Although well documented in the English literature, some surgeons doubt the existence of SMAS as a real entity. SMAS is characterized by extrinsic compression of the third part of the duodenum between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), due to narrowing of the aortomesenteric angle, and results in acute or chronic intermittent duodenal obstruction.

CASE REPORT

A 66-year-old man, with no previous medical history, presented with severe upper abdominal pain and distension that had been present for a few days. He had no history of nausea, vomiting, recent weight loss, altered bowel habits, or previous abdominal surgery. On examination, he was alert, afebrile, with a pulse rate of 107/min and blood pressure of 155/95 mm Hg. The abdomen was distended, tympanic, with positive succussion splash and epigastric tenderness. A bedside ultrasound showed an incidental 4-cm abdominal aortic aneurysm. The initial blood investigations were normal. An urgent computerized tomography (CT) scan revealed marked distension of the stomach and proximal duodenum with narrowing of the third part of the duodenum between the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and aorta (Figure 1). The sagittal-CT showed a marked narrowing of the aortomesenteric angle (white arrow) to 8.6 degrees compatible with a diagnosis of superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS) (Figure 2). The incidental 4cm infra-renal aortic aneurysm showed no leak or rupture. The patient's symptoms improved with nasogastric decompression, and he got himself discharged against medical advice the next day. He presented again in the emergency department 2 days later with similar symptoms, bilious vomiting and severe dehydration. After fluid resuscitation and nasogastric decompression, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed. It showed a dilated stomach with no outlet obstruction. The first and second parts of the duodenum were dilated with a collapsed lumen in the third part. The scope, however, could pass through the third part. Gastrografin administration showed hold up of contrast in the third part of the duodenum with proximal dilatation and slow passage into the distal small bowel (Figure 3). Conservative management with nasojejunal feeds was not successful because the patient was non-compliant and refused tube feeding. He required a surgical bypass for long-term relief. A laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy was successfully performed.

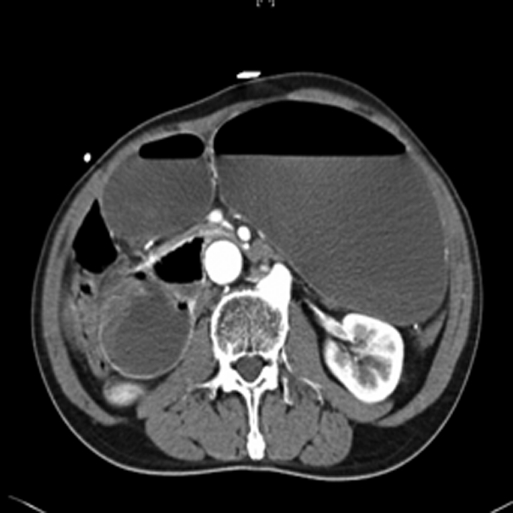

Figure 1.

Axial computed tomographic scan showing markedly dilated stomach and proximal duodenum with compression of the third part of the duodenum between the SMA and aorta.

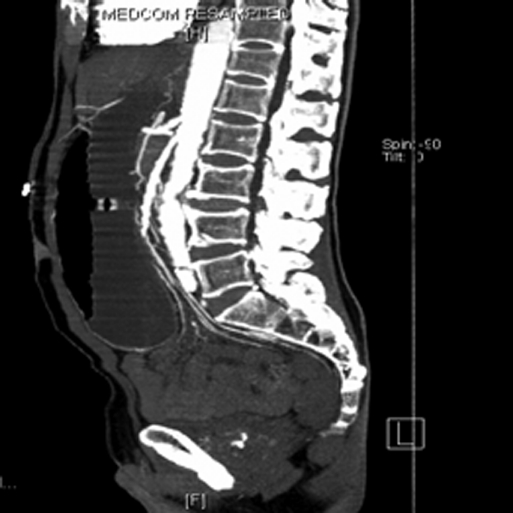

Figure 2.

Sagittal computed tomographic scan showing a narrowed aortomesenteric angle of 8.6 degrees.

Figure 3.

Preoperative Gastrografin meal showing a dilated proximal duodenum with hold up of contrast in the third part and delayed passage distally.

Operative Technique

The patient, while under general anesthesia, was positioned supine with both legs abducted to allow the surgeon to stand in between. Four ports were inserted - 1st port (10-mm camera): supraumbilical; 2nd port (5 mm): left midclavicular line midway between the umbilicus and costal margin; 3rd port (12 mm): right midclavicular line midway between the umbilicus and costal margin; 4th port (5 mm): epigastrium (Figure 4). A complete diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. The small bowel was traced from the duodenojejunal (DJ) flexure to the cecum and found to be normal. The hepatic flexure, transverse mesocolon, and gastrocolic omentum were mobilized to visualize the duodenum and the head of the pancreas, which were elevated by the underlying aortic aneurysm. The proximal dilated duodenum was kocherized. An on-table EGD helped in visualization and kocherization of the dilated duodenum with Harmonic shears. A proximal loop of jejunum about 25 cm from the DJ-flexure was brought below the dilated duodenum and fixed with it by using interrupted seromuscular 2– 0 Vicryl sutures. The duodenum and jejunal lumen was then opened by using hook diathermy, and an EndoGIA stapler (Ethicon Endosurgery, Somerville, NJ) was inserted and fired (Figure 5). After confirming hemostasis of the staple line, the openings in the duodenum and jejunum were sutured together with continuous full-thickness 2– 0 Vicryl sutures. The anastomosis was tested for a leak, by instillation of methylene blue solution via the nasogastric tube. A tube drain was placed adjacent to the anastomosis, and the 10- and 12-mm port sites closed. The duration of surgery was 130 minutes, and blood loss was 150 mL. The patient made an uneventful recovery. A Gastrografin meal study on the fifth postoperative day showed the anastomosis to be functioning well with no contrast leak (Figure 6). He tolerated oral feeds and diet and was discharged on the seventh postoperative day. The delay in discharge was due to social reasons and transfer to a step-down facility. The patient remained well and asymptomatic during follow-up at 1 and 3 months.

Figure 4.

Position of trocar sites on the patient.

Figure 5.

Stapled side-to-side laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy.

Figure 6.

Postoperative day 5 Gastrografin meal showing no leak with free flow into jejunum across the anastomosis.

DISCUSSION

About 400 cases have been described in the English literature with a slight female preponderance.2 The availability of dynamic CT-scans has made the diagnosis of this rare and controversial condition much easier. Normally, the SMA leaves the aorta at an angle of 45 degrees, and it is through this aortomesenteric vascular angle that the third part of the duodenum passes through. A mass of fat and lymphatic tissue around the SMA normally provides an adequate cushion to prevent extrinsic duodenal compression. Any condition that narrows the aortomesenteric angle to approximately 6 degrees to 16 degrees can lead to SMAS.2,3 In our patient, the angle was narrowed to 8.6 degrees. He also had an accompanying 4-cm infrarenal aortic aneurysm that may have contributed to this narrowed angle. SMAS has been previously reported in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms.4 Table 1 gives a list of risk factors leading to this condition. Ahmed and Taylor3 stressed the importance of differentiating SMAS from other conditions causing a similar clinical picture, such as scleroderma, systemic sclerosis, diabetes, myotonic dystrophy, and myxoedema. Gondos5 suggested that the compression in these cases is brought on by dilatation and loss of muscle tone of the duodenum with secondary imprinting of the duodenum by the SMA. The diagnosis of SMAS is difficult and one of exclusion. Clinical features are not pathognomonic. In acute cases, patients may present with features of acute gastric dilatation or proximal small bowel obstruction depending on whether the vomitus is bile-stained. The majority of cases are however chronic and present many times over several years for investigation of episodic upper abdominal pain with vomiting, anorexia, and early satiety. Typically, the pain is relieved by postural changes that increase the angle between SMA and the aorta. A high index of suspicion, in the presence of known risk factors, is the key to early diagnosis and avoiding complications like massive gastric dilatation, necrosis, or even perforation. Investigations like abdominal x-rays usually reveal a dilated stomach and proximal duodenum but are nonspecific. Endoscopy does not indicate the diagnosis but is important to rule out more common intraluminal causes of obstruction. Barium or Gastrografin contrast findings suggestive of SMAS are dilatation of the stomach, first and second parts of the duodenum, abrupt vertical or linear cutoff of contrast in the third part of the duodenum with normal mucosal folds, delay of 4 hours to 6 hours in gastroduodenal transit and reverse peristalsis in the proximal dilated duodenum. With the advent of modern CT scanners, investigations like hypotonic duodenography and SMA arteriography are rarely used nowadays. The dynamic CT-scan is a safe, rapid, noninvasive diagnostic tool, which can clearly demonstrate the compression of the duodenum between the SMA and aorta and the narrowed aortomesenteric angle. Conservative treatment of SMAS involves nasogastric decompression, prokinetic agents to improve gastrointestinal transit, and reversing or removing the precipitating factor. Nutrition may be either in the form of small, frequent feeds in the left lateral or knee-chest posture, or nasojejunal feeding, or total parenteral nutrition. The aim is to provide a high-calorie diet to increase mesenteric fat and expand the aortomesenteric angle. Approximately 6 weeks to 8 weeks are needed before favorable results are seen. Surgical intervention is indicated when conservative methods fail. In our patient, conservative management was attempted, but the patient was noncompliant and refused prolonged tube feeding. We, therefore, decided to perform a surgical bypass for a definitive cure.

Table 1.

Risk Factors That Predispose to Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome

| Dietary disorders like anorexia nervosa, malabsorption syndromes severe wasting from catabolic states like cancers, burns |

| Spinal disease or deformity causing increased lordosis severe trauma, paralysis, head injury causing prolonged immobilization use of plaster body casts for scoliosis or vertebral fractures (cast syndrome) |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysms |

| Rapid linear body growth without accompanying weight gain |

Several surgical procedures have been described in the literature. Strong's technique6 of mobilizing the duodenum by dividing the ligament of Treitz has the benefit of avoiding an anastomosis but an unacceptably high failure rate. Gastrojejunostomy, due to inadequate decompression of the duodenum and the high risk of stomal ulceration, is controversial.2 Duvie7 has described transposition of the third part of the duodenum anterior to the superior mesenteric vessels to permanently circumvent the obstruction. Duodenojejunostomy, first described by Staveley,8 remains the most frequently performed and favored operation over the years, with excellent results. Gersin et al9 were the first to report a laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy for SMAS. Subsequent successful results with acceptable operating time, faster recovery, and shorter hospitalization have been reported by other authors.2,10 In our case, laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy showed excellent results with rapid recovery and relief of symptoms until the final follow-up at 6 months. It gives the same results as open surgery with all the advantages of a minimally invasive procedure and should be the treatment of choice whenever surgical correction of SMAS is indicated.

References:

- 1.Wilkie DPD. Chronic duodenal ileus. Am J Med Sci. 1927;173:643–49 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Senthilkumar R, Parthasarathi R, Jani K. Laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy for superior mesenteric artery syndrome. JSLS. 2006;10:531–534 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed AR, Taylor I. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73:776–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamont PM, Clarke PJ, Collin J. Duodenal obstruction after abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1992;6:107–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gondos B. Duodenal compression defect and the superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Radiology. 1997;123:575–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strong EK. Mechanics of aortomesenteric duodenal obstruction and direct surgical attack upon aetiology. Ann Surg. 1958;148:725–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duvie SO. Anterior transposition of the third part of the duodenum in the management of chronic duodenal compression by the superior artery. Int Surg. 1988;73:140–143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Staveley AL. Chronic gastromesenteric ileus. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1910;11:288–291 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gersin KS, Heniford BT. Laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy for treatment of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. JSLS. 1998;2:281–284 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson WS, Surowiec WJ. Laparoscopic repair of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Am J Surg. 2001;181:377–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]