Abstract

Surgeons are gaining interest in natural orifice surgery because of its minimally invasive nature. The new paradigm shift of using a natural orifice, as opposed to the abdominal wall, as a conduit for entry into the abdomen has resulted in novel solutions to solving difficult surgical problems. Repetitive foreign body ingestion continues to be one of those challenging dilemmas. Ingested objects that cannot be retrieved endoscopically must be removed by laparoscopy or laparotomy. Surgical removal, however, becomes more difficult with each subsequent operation. We report a novel technique of foreign body removal that utilizes the concept of natural orifice surgery by combining both laparoscopic and endoscopic techniques.

Keywords: Foreign body, Laparoscopy, Endoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Repetitive foreign body ingestion, although a common clinical pediatric problem, is relatively rare in the adult population and occurs primarily in individuals with psychiatric conditions, such as bipolar disorder, depression, or posttraumatic stress disorder. Described ingested objects include fish bones,1 needles, razor blades, and pins. In most cases, these objects pass spontaneously with no clinical sequelae. Alternatively, these objects can be retrieved by indirect laryngoscopy or flexible endoscopy. Complications that may arise with nonsurgical modalities, however, include perforation, migration to the liver and pancreas,2,3 pancreatitis, development of gastric varices, splenic artery pseudoaneurysm,4 or even appearance that is indistinguishable from locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma.5 In these cases, laparoscopy6 or exploratory laparotomy is usually necessary. A subset of psychiatric patients has a history of multiple foreign body ingestions and multiple prior surgical interventions, making successive laparoscopy and laparotomy more hazardous to the patient. We report the case of a patient with a history of multiple ingestions who had undergone multiple endoscopies and laparotomies for ingested foreign bodies and describe an innovative technique for removal of foreign bodies not amenable to endoscopic retrieval.

CASE REPORT

The patient is a 54-year-old male with at least 10 previous ingestions of razor blades and nails and at least 7 prior laparotomies for removal. At admission 3 months earlier for ingestion of 2 razor blades, attempted fluoroscopic-guided endoscopic retrieval was complicated by a contained distal esophageal perforation, and only one of the 2 objects was retrieved. The remaining blade was removed after an extensive exploratory laparotomy requiring 4 hours of adhesiolysis and a large gastrotomy with fluoroscopic guidance for retrieval of the remaining razor blade. The patient spent 15 days in the hospital following his surgery. His past medical history was also notable for HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C, polysubstance abuse, posttraumatic stress disorder, and bipolar disorder. At the current admission, the patient presented with abdominal pain, normal hemodynamics, and no peritonitis. He was found to have a hemoglobin of 9.2, white blood cell count of 5.1, prothrombin time of 16.2, and INR of 1.2. Abdominal films demonstrated no free air, and 2 razor blades were noted in his stomach (Figure 1). An extensive discussion was held between the general surgery, gastroenterology, psychiatry, ethics, and medical legal services. Because of the patient's recent esophageal perforation following attempted endoscopic retrieval and the low likelihood of spontaneous passage of the razor blades, it was decided that the best course of action was surgical retrieval.

Figure 1.

An abdominal radiograph of the patient showing one of two ingested razor blades.

After informed consent was obtained, the patient was administered general anesthesia. He had numerous other well-healed incisions from prior laparotomies, which included a large midline incision, a left and right subcostal incision, a left paramedian incision, a right lower quadrant transverse incision, and a horizontal upper abdominal incision. Based on the plain radiographs, we chose to make a small midline (4 cm) incision overlying his stomach through his previous midline scar. This incision was carried down to the peritoneum, which when sharply entered was found to have extensive adhesions. A 4-cm portion of the anterior stomach was mobilized. After a pursestring suture was placed, a 1.5-cm gastrotomy was created through which a 12-mm balloon port was placed (Figures 2, 3, 4). Upper GI endoscopy was then performed, which showed 2 razor blades in the cephalad portion of the stomach. Using the endoscope as an intraluminal light source, insufflator, and camera, a laparoscopic grasper was placed through the balloon port to grab and atraumatically remove the 2 razor blades, located high in the fundus near the gastroesophageal junction. The gastrotomy was then closed in 2 layers. The midline fascia was closed, and the skin was closed with staples. The patient was extubated in the OR and taken to the recovery room in stable condition. He had an uncomplicated postoperative course and was tolerating a diet by postoperative day 3. On postoperative day 6, he was discharged in stable condition to a monitored living facility.

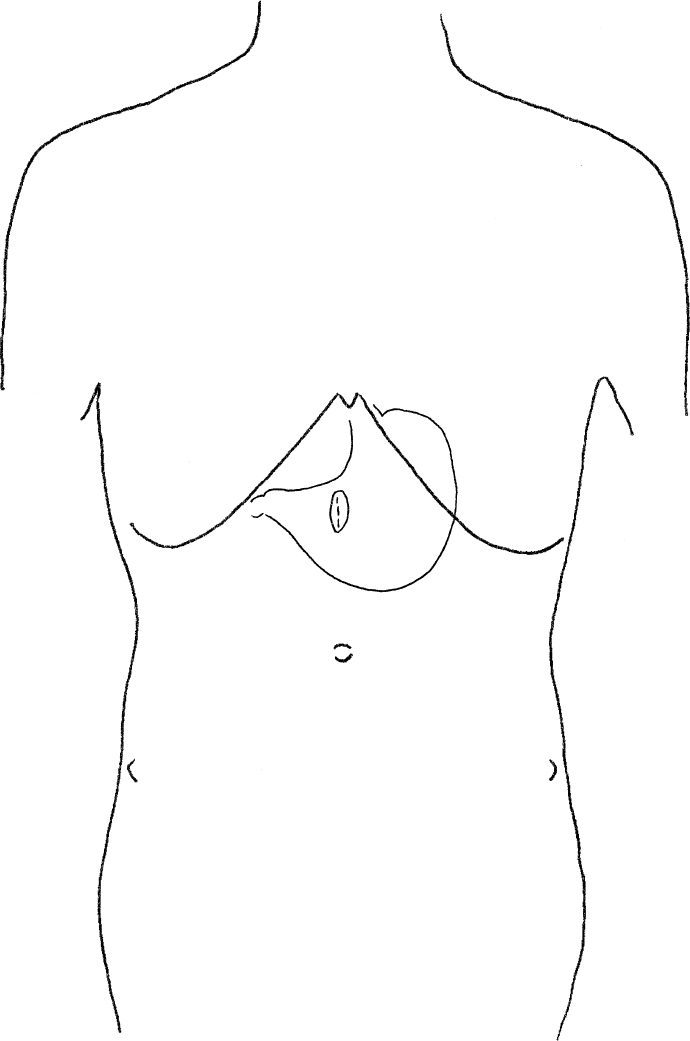

Figure 2.

An illustrated diagram of the 4 cm midline incision and the 1.5 cm gastrotomy.

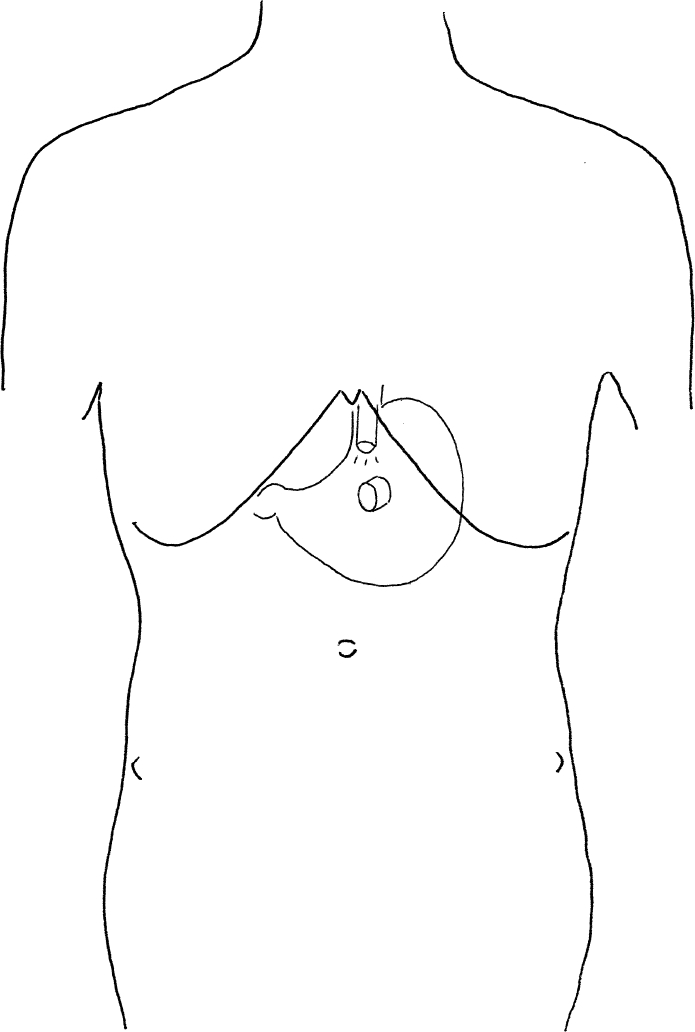

Figure 3.

A 12 mm balloon port was placed through the 1.5 cm gastrotomy. The endoscope was passed to explore for any esophageal or gastric injury.

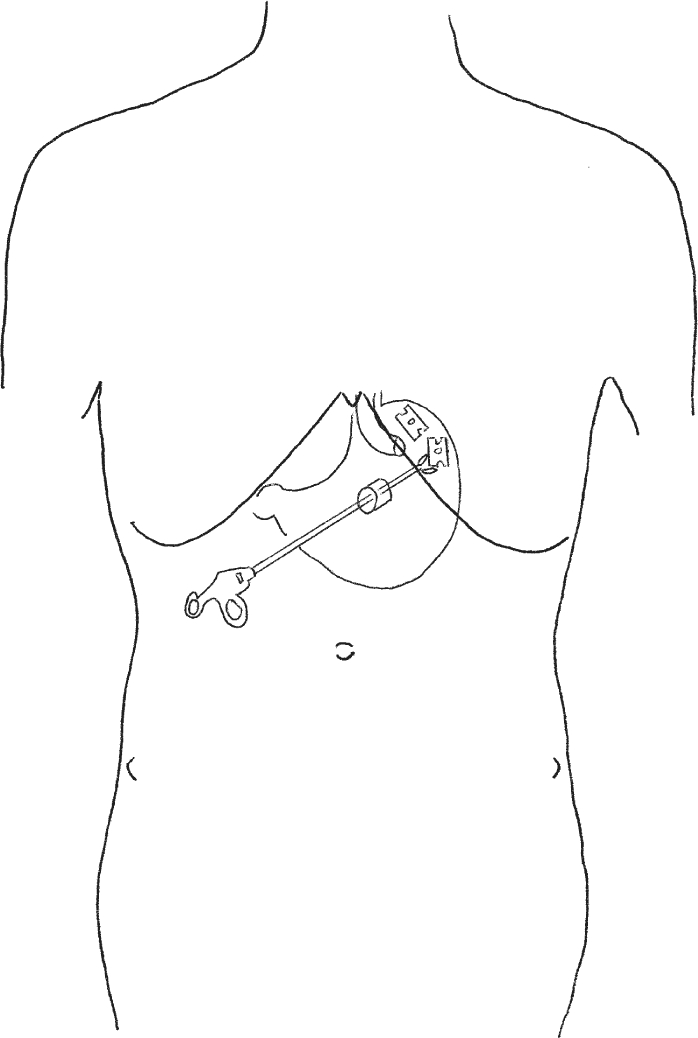

Figure 4.

The endoscope was retroflexed towards the fundus to visually localize the two razor blades. A laparoscopic grasper was inserted through the balloon port, and the two razor blades were removed atraumatically.

DISCUSSION

While endoscopic removal is feasible in most cases of foreign body ingestion in which spontaneous passage is not successful or possible, surgical exploration is occasionally necessary. Although laparoscopic exploration and retrieval may be preferable in such circumstances, in patients with multiple prior abdominal surgeries, access to the peritoneal cavity may be difficult to obtain and may involve extensive adhesiolysis with its attendant risks of bowel injury and prolonged operative time and may be compromised by poor visualization and exposure, increasing the potential morbidity to the patient and the frustration of the surgeon. These difficulties are inherent during conventional laparotomy in this setting as well. As such, an innovative approach in these instances may minimize these risks to both the patient and surgeon.

The development and application of natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) has generated substantial interest amongst surgeons, gastroenterologists, and the medical device industry. The feasibility of NOTES has been demonstrated in porcine models of the peroral transgastric endoscopic approach to the peritoneal cavity for the performance of cholecystectomy,7 gastrojejunostomy,8 splenectomy,9 oophorectomy and salpingectomy,10,11 and tubal ligation.12 More recently, NOTES appendectomies and laparoscopic-assisted NOTES cholecystectomies have been performed both via the transvaginal and transgastric route in humans. Substantial technical hurdles to be overcome include optimization of gastric/visceral closure, prevention of infection, development of endoscopic suturing and anastomotic devices, multi-tasking platforms, and adequate physician training. This paradigm shift of using a natural orifice to access the peritoneal cavity as opposed to the use of abdominal wall incision(s) offers a tremendous opportunity for innovation and creative problem solving for surgeons, endoscopists, engineers, and industry.

We report the first described case of foreign body removal using an approach we have termed “reverse NOTES”: rather than creating a gastrotomy endoscopically using a natural orifice, gastric access was obtained via limited, radiograph-guided laparotomy; endoscopy provided the necessary visualization and insufflation, and conventional laparoscopic instrumentation was utilized for object retrieval. In reviewing our approach, we propose that an alternative for the positioning of the laparotomy would have been to use endoscopy to transilluminate the abdominal wall in a manner similar to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Additionally, the use of carbon dioxide, rather than air insufflation, may have been preferable with regards to bowel and abdominal distention, were conversion to conventional laparotomy necessary. The endoscopic intragastric visualization we were able to obtain was superior to that of conventional “open” gastrotomy, particularly with regards to examination of the cardia and fundus, and greatly simplified the removal of the razor blades and avoided exposure to the radiation associated with fluoroscopy. Another alternative for endoscopic retrieval includes usage of a large overtube for safer retrieval of sharp objects. Also, placing a PEG tube at the site of the gastrotomy would provide future access to the stomach should the need arise. An obvious prerequisite to our approach is the need for endoscopic expertise either on the part of the surgeon or with the involvement of an additional endoscopist.

While the flurry of research and development associated with NOTES is remarkable and necessary, an equally important byproduct of this intersection of endoscopy, laparoscopy, and open surgery is the opportunity for clinicians to “re-think” difficult clinical problems and develop innovative solutions using currently available therapies. As such, we hope that this case report provides an example of such opportunities to the practicing surgeon.

References:

- 1. Ngan JHK, Fok PJ, Lai ECS, Braniki FJ, Wong J. A prospective study on fish bone ingestion. Experience of 358 patients. Ann Surg. 1990;211(4):459–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rahalkar MD, Pai B, Kukade G, Al Busaidi SS. Sewing needles as foreign bodies in the liver and pancreas. Clin Radiol. 2003;58(1):84–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goh BKP, Yong W, Yeo AWY. Pancreatic and hepatic abscess secondary to fish bone perforation of the duodenum. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(6):1103–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kim KH, Woo EY, Rosato EF, Kochman ML. Pancreatic foreign body: ingested toothpick as a cause of pancreatitis and hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59(1):147–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goh BKP, Jeyaraj P, Chan H, et al. A case of fish bone perforation of the stomach mimicking a locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 49(11/12):1935–1937, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu C, Hungness ES. Laparoscopic removal of a pancreatic foreign body. J Soc Laparoendosc Surg. 2006;10(4):541–543 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Park PO, Bergstrom M, Ikeda K, Fritscher-Ravens A, Swain P. Experimental studies of transgastric gallbladder surgery: cholecystectomy and cholecystogastric anastomosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(4):601–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kantsevoy SV, Jagannath SB, Niiyama H, et al. Endoscopic gastrojejunostomy with survival in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:287–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kantsevoy SV, Hu B, Jagannath SB, et al. Transgastric endoscopic splenectomy: is it possible? Surg Endosc. 2006;20(3):522–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wagh MS, Merrifield BF, Thompson CC. Endoscopic transgastric abdominal exploration and organ resection: initial experience in a porcine model. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3(9):892–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wagh MS, Merrifield BF, Thompson CC. Survival studies after endoscopic transgastric oophorectomy and tubectomy in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(3):473–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jagannath SB, Kantsevoy SV, Vaughn CA, et al. Peroral transgastric endoscopic libation of fallopian tubes with long-term survival in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:449–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]