Abstract

Background and Objectives:

In 1999, our institution began a kidney transplant program with collaboration between the departments of General Surgery/Transplantation and Urology. From the onset, donor nephrectomies were performed laparoscopically and are currently the domain of Urology, which had no prior laparoscopic experience before this undertaking. We reviewed our experience.

Methods:

A database of our experience was kept prospectively from June 1999 to November 2004. Records of both donors and recipients were reviewed. Special attention was directed toward our changes in technique and their relationship to outcomes, with emphasis on graft extraction and overall complication rates.

Results:

We reviewed the records of 205 consecutive procedures. We report excellent donor outcomes, including mean operative time (112 minutes), estimated blood loss (120 mL), and length of stay (2.3 days). Complication (14.1%) and open conversion (1.5%) rates were low. For the recipients, early (98.0%) and 1-year (94.7%) graft survival, and ureteral ischemia (2.4%) rates were also appropriate with contemporary experience.

Conclusions:

We report our results on laparoscopic donor nephrectomy in a de novo renal transplant program. Because of this experience, we have ventured into other horizons of urologic laparoscopy and currently produce enough volume to support a laparoscopic fellowship. We feel that a productive donor nephrectomy program can enhance urologic laparoscopic programs and should be taken advantage of when available.

Keywords: Laparoscopy, Nephrectomy, Transplant

INTRODUCTION

Since it was first described in 1995, laparoscopic donor nephrectomy (LDN) has replaced its open counterpart in many transplant centers throughout the country. Reasons for this phenomenon are well documented and include less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stay, shorter convalescence, and better cosmesis. Moreover, the appeal of these clear benefits to the donor has been credited to increasing the willingness of individuals to undergo live kidney donations.1

At our institution, we developed a renal transplant program in 1999. At the incipience, live kidney donations were performed laparoscopically as a cooperative effort between the departments of general surgery and urology but eventually became the domain of urology. Because we had minimal laparoscopic experience, one surgeon (PEA) was mentored through the first 35 cases by a general surgeon with laparoscopic expertise. In addition to hands-on mentoring in the operating room with an experienced laparoscopic surgeon, this urologist spent over 40 hours in the dry lab practicing basic laparoscopic hand movements and laparoscopic suturing and tying on a pelvic trainer, using a regimen set up for general surgery residents at our institution. Since that time, we have performed over 200 LDN. Because of the vast laparoscopic experience that we have obtained through LDN and the heavy caseload at our institution, soon after initiating the LDN program, we began to expand our realm of laparoscopic surgery to include all variety of minimally invasive retroperitoneal and pelvic procedures. Our current volume supports a fellowship in minimally invasive and robotic urologic surgery. Our fellows undergo similar dry lab training and hands-on mentoring as was practiced by the initiator of the program.

We describe our experience with the LDN, focusing on technique and operative outcomes.

METHODS

The records of all patients who underwent LDN at our institution from June 1999 until November 2004 were reviewed after approval was obtained from our institutional review board. All cases have been performed exclusively by or under the tutelage of one surgeon (PEA). We screen all of our potential kidney donors as per the guidelines set forth by the American Society of Transplantation and have not excluded anyone who would have otherwise undergone an open donor nephrectomy.2 In addition to this preoperative screening, all patients undergo a computed tomographic (CT) angiogram with 3-dimensional volume renderings and a CT urogram before the procedure.

We use a transperitoneal approach for both left- and right-sided LDN. Pneumoperitoneum is established through a hand port that is placed through either a lower midline or Pfannenstiel incision at the beginning of each case. Although the entire dissection is performed purely laparoscopically, the hand port facilitates specimen extraction and was a change in our technique that we used after our 68th case (June 2002). Our laparoscopic approach to the renal hilum is similar to what we have previously described for an oncological procedure3; particular to the LDN dissection is that we develop the plane between Gerota's fascia and the renal parenchyma and leave a thick tail of Gerota's fascia over the proximal ureter to ensure adequate blood supply. The renal vein and renal artery on both sides are secured with an Endostapler Linear Cutter endoscopic articulating stapler (Ethicon Endo-surgery, Inc, Cincinnati, Ohio) unless intraoperative evaluation reveals early vessel branching or a potential for inadequate vessel length, for which we use Hem-o-lok clips (DuPont Corporation, Wilmington, Delaware). Intravenous mannitol, furosemide, and ample hydration are administered throughout the case to maintain high urine output and prevent arterial spasm, and intravenous heparin is administered 3 minutes before arterial division to prevent thrombosis. Recipient considerations, including graft preparation and implantation, and postoperative care and follow-up, are managed by a separate transplant team.

Patient demographics, operative details, complications, and donor and recipient outcomes were evaluated.

RESULTS

In the time period of interest, we performed 205 LDN. Patient demographics and operative details are listed in Table 1. Consistent with prior reports, there were significantly more women donors than men.4 Over 14% (30 total) of the kidneys that we used were right-sided, and about 10% of the total donor grafts had multiple renal arteries.

Table 1.

Donor Demographics and Perioperative Details (N = 205)

| Mean Age (yr) | 40.9 ± 11.2 |

| Male/Female | 76/129 |

| Right/Left | 30/175 |

| Multiple Renal Arteries | 22 (10.7%) |

| Mean Operating Time (min) | 112 ± 39.5 |

| Average Extraction Time (min) | 1.6 ± 1.1 |

| Estimated Blood Loss (mL) | 120 ± 230 |

| Open Conversions | 3 (1.5%) |

| Complications | 29 (14.1%) |

| Length of Stay (days) | 2.3 ± 0.9 |

Although we did not include warm ischemia times, we feel that an equally important variable particular to LDN is the time that it takes to extract the kidney from the donor once the renal artery had been clamped before firing the stapler (the extraction time). Early in our series, we extracted through a lower midline or Pfannenstiel incision utilizing a laparoscopic entrapment bag. On one occasion, however, we encountered a cortical fracture to the graft during specimen entrapment, and although this did not affect the utility or long-term function of the donor kidney, it did concern us enough to change our technique of extraction. Starting with our 69th case, we began to establish pneumoperitoneum through a hand port that we placed at the beginning of the case and later used for specimen extraction. This change resulted in a significant decrease in our extraction time; and more importantly, it eliminated the possibility of cortical damage from the specimen entrapment bag. Mean extraction time for cases 1 through 68 was 3.16 minutes and 1.16 minutes for cases 69 through 205. In addition, the hand port allows us to manually break any residual attachments to the kidney on extraction, thus making this process more efficient.

Estimated blood loss and open conversion rates for our LDN are consistent with what has been reported in the literature. Open conversions were related to failure to progress in an obese patient and 2 cases of vascular injury after stapler malfunction. Excluding these conversions, there were 7 intraoperative and 22 postoperative (8 major, 14 minor) complications, for a total of 29 or 14.1%. Of note, there were no intraoperative bowel injuries, one intraoperative blood transfusion (on an open conversion), and 2 postoperative blood transfusions in our entire series (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perioperative Complications (Including Open Conversions)

| Intraoperative Complications | |

| Vascular injury | 5 |

| Splenic injury | 3 |

| Cortical fracture | 1 |

| Pneumothorax | 1 |

| Major Postoperative Complications | |

| Pneumonia | 3 |

| Retroperitoneal hematoma with transfusion | 2 |

| Respiratory distress | 2 |

| Hematuria requiring fulguration | 1 |

| Minor Postoperative Complications | |

| Ileus | 3 |

| Urinary retention | 3 |

| Retroperitoneal hematoma without transfusion | 2 |

| Wound infection | 1 |

| Epididymitis | 1 |

| Ear hematoma | 1 |

| Hematuria resolved spontaneously | 1 |

| Refractory nausea | 1 |

| Retroperitoneal abscess | 1 |

Our patients are all placed on a care map, which mandates hospital discharge on postoperative day 2. All but 33 patients were discharged on or before this time, and of those who were not, the average discharge day was 3.6 (range, 3 to 7).

Recipient demographic and graft survival details are reported in Table 3. Because of our regional patient population, most of our renal transplant recipients are Caucasian, and in this series, there were only 24 representing other ethnic backgrounds (10 American Indian, 9 African/ African American, 2 Middle Eastern/Arabian, 2 Pacific Islander, and 1 Asian). United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) criteria to measure early and delayed graft function are addressed in this table as is our ureteral stricture rate (5/205 or 2.4%).

Table 3.

Recipient Demographics and Graft Survival (N = 205)

| Mean Age (yr) | 49.7 ± 13.5 |

| Male/Female | 126/79 |

| Caucasian | 181 (88.3%) |

| Mean sCr at Transplant (mg/dL) | 7.3 (2.0–17.9) |

| >40 mL Urine During First 24 hr | 201 (98.0%) |

| >25% Decrease in sCr at Initial Hospital Discharge | 168 (82.0%) |

| Treated for Rejection During Transplant Admission | 33 (16.1%) |

| Length of Stay (days) of Transplant Admission | 4.7 ± 1.8 |

| Mean sCr at 6 Months (mg/dL) | 1.41 ± 0.48 |

| Mean sCr at 1 Year (mg/dL) | 1.37 ± 0.5 |

| Graft Survival at 1 Year | 161/170 (94.7%) |

| Ureteral Stricture | 5 (2.4%) |

DISCUSSION

The merits of LDN and its benefits when compared with open donor nephrectomy have been well argued, and we do not seek to continue this debate.5–9 Instead, we undertook our renal transplant program considering LDN as the emerging standard for live renal procurement and to date have not performed any open donor procedures. In addition, we realized the power of minimal invasiveness in motivating live kidney donors, and to this date live donations represent 60% of all renal transplantations at our institution. We report excellent results with respect to both donor outcomes and graft survival, both of which are consistent with what has previously been reported.4,9

Our technique for LDN has evolved as our experience has increased, but overall has not changed significantly. We noted that 2 technical alterations positively affected our outcomes. The first was limiting the placement of titanium clips around the renal hilum, especially when using a stapler to secure the vessels. The second alteration was incorporating a hand port into our method of extraction. The use of a hand port in LDN is not foreign, and several groups report excellent outcomes with hand-assisted LDN.10,11 Still, we prefer the dissection that can be obtained through pure laparoscopy and do not use the hand port until the ureter and vessels have been divided and the specimen needs a quick and safe removal. Indeed, we noticed a significant difference in extraction time immediately after use of the hand port, starting with case #69. This result would have an indubitable effect on warm ischemia time and graft survival. Accordingly, we did look at graft survival both before and after incorporation of the hand port, but found no difference between the 2 techniques. Still, the relative ease of extraction using the hand port when compared with the laparoscopic entrapment bag and the decreased potential trauma to the graft has convinced us to continue with this modification to our technique.

Almost 15% of our LDN were of the right kidney. There are technical considerations when performing the right LDN, and this has prompted some groups to recommend technique modifications.12,13 Despite these modifications, the outcomes with left- versus right-sided LDN are similar.14,15 We continue to use a transperitoneal 3-port approach on the right side as on the left, and use a second 5-mm port for a self-retaining liver retractor. In addition, we use the same articulating stapler to divide the vessels as for a left LDN. Interestingly, when reviewing our series, we noted a shorter mean operative time for the right side versus the left side (103.1 vs 113.5 minutes) and discovered that all 30 of our right LDN grafts had survived at 1 year. As a result, although we preferentially perform a left LDN, when indicated we will use the right kidney with similar outcomes.

Experimental observations have demonstrated that pneumoperitoneum decreases cortical renal blood flow, renal vein flow, and creatinine clearance, and causes oliguria.16–18 However, no permanent adverse effects of pneumoperitoneum on function or histology of native kidneys has been described. These findings are supported by the demonstration of decreased early posttransplant graft function in laparoscopically harvested grafts but equivalent long-term survival.4 Our early (98.0%) as well as 1-year (94.7%) graft survival rates are uniform with contemporary series of LDN.4,9

Ureteral ischemia to the recipient can be a devastating complication, and this problem is often attributed to the donor nephrectomy surgical technique. Ureteral complication rates have been reported to be as high as 31% in some series but have also been noted to improve with LDN experience and an enhanced appreciation of periureteral anatomy.5,9,19 Accordingly, we attribute our low ureteral complication rate (2.4%) to leaving a thick tail of Gerota's fascia around the proximal ureter, mobilizing the tissue medial to the gonadal vein to be included in the packet and limiting sharp dissection in this area to rely instead more on blunt separation of this packet from surrounding tissues.

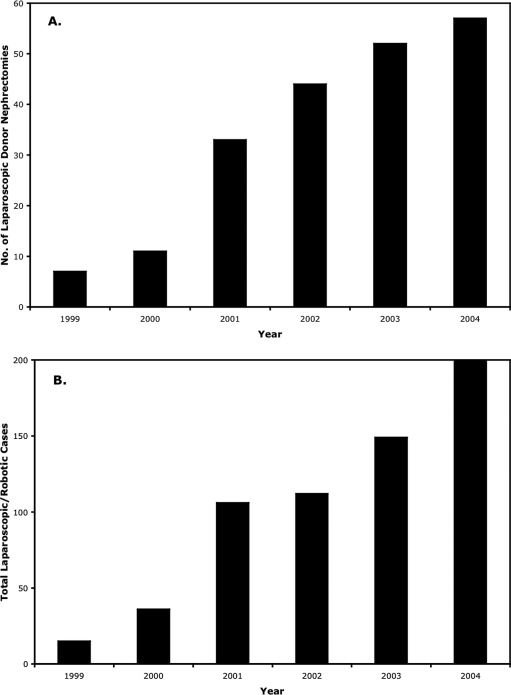

The experience we have obtained from LDN has greatly expanded our confidence in laparoscopy with regard to other procedures. Before our first LDN, we performed a total of 4 laparoscopic cases. In the last year, we performed approximately 200, with roughly one third of those consisting of LDN. Accordingly, over the last 5 years, as our LDN program has expanded, so has our total laparoscopic program, and over each year, LDN has comprised at least one third to one half of our total laparoscopic procedures (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual distribution of laparoscopic donor nephrectomy (A) and corresponding total number of laparoscopic and robotic cases (B) performed in the same time period at our institution.

As the laparoscopic approach to renal surgery solidifies its position as the gold standard for multiple procedures, increased volume can only enhance familiarity with perirenal anatomy and the comfort level with laparoscopic surgery in this area, and LDN can provide that extra experience. For example, the dissection that we have refined for the LDN is one in the same with that for a laparoscopic partial nephrectomy with hilar clamping. We believe that the LDN can be invaluable to a laparoscopic training program and should be taken advantage of when possible.

CONCLUSION

We report our results after 5 years of LDN and show excellent results with regard to perioperative donor outcomes and graft survival with low complication rates. In addition, we demonstrate how a small modification in our extraction technique has positively impacted this procedure. Finally, we believe that LDN is a valuable tool for urology training programs and should be capitalized upon when available.

Contributor Information

Costas D. Lallas, Department of Urology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA..

Erik P. Castle, Department of Urology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA..

Richard T. Schlinkert, Department of General Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA..

Paul E. Andrews, Department of Urology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, USA..

References:

- 1. Ratner LE, Montgomery RA, Kavoussi LR. Laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy. A review of the first 5 years. Urol Clin North Am. 2001; 28: 709– 719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kasiske BL, Ravenscraft M, Ramos EL, et al. The evaluation of living renal transplant donors: clinical practice guidelines. Ad Hoc Clinical Practice Guidelines Subcommittee of the Patient Care and Education Committee of the American Society of Transplant Physicians. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996; 7: 2288– 2313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Simon SD, Ferrigni RG, Novicki DE, et al. Mayo Clinic Scottsdale Experience with laparoscopic nephroureterectomy. JSLS. 2004; 8: 109– 113 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Troppmann C, Ormond DB, Perez RV. Laparoscopic (vs open) live donor nephrectomy: a UNOS database analysis of early graft function and survival. Am J Transplant. 2003; 3: 1295– 1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Philosophe B, Kuo PC, Schweitzer EJ, et al. Laparoscopic versus open donor nephrectomy: comparing ureteral complications in the recipients and improving the laparoscopic technique. Transplantation. 1999; 68: 497– 502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. London E, Rudich S, McVicar J, et al. Equivalent renal allograft function with laparoscopic versus open liver donor nephrectomies. Transplant Proc. 1999; 31: 258– 260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sasaki TM, Finelli F, Bugarin E, et al. Is laparoscopic donor nephrectomy the new criterion standard? Arch Surg. 2000; 135: 943– 947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leventhal JR, Deeik RK, Joehl RJ, et al. Laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy—is it safe? Transplantation. 2000; 70: 602– 606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tooher RL, Rao MM, Scott DF, et al. A systematic review of laparoscopic live-donor nephrectomy. Transplantation. 2004; 78: 404– 414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rudich SM, Marcovich R, Magee JC, et al. Hand-assisted laparoscopic donor nephrectomy: comparable donor/recipient outcomes, costs, and decreased convalescence as compared to open donor nephrectomy. Transplant Proc. 2001; 33: 1106– 1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stifelman MD, Hull D, Sosa RE, et al. Hand assisted laparoscopic donor nephrectomy: a comparison with the open approach. J Urol. 2001; 166: 444– 448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Turk IA, Giessing M, Deger S, et al. Laparoscopic live donor right nephrectomy: a new technique with preservation of vascular length. Transplant Proc. 2003; 35: 838– 840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ng CS, Abreu SC, Abou El-Fettouh HI, et al. Right retroperitoneal versus left transperitoneal laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy. Urology. 2004; 63: 857– 861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Swartz DE, Cho E, Flowers JL, et al. Laparoscopic right donor nephrectomy: technique and comparison with left nephrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2001; 15: 1390– 1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lind MY, Hazebroek EJ, Hop WC, et al. Right-sided laparoscopic live-donor nephrectomy: is reluctance still justified? Transplantation. 2002; 74: 1045– 1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chiu AW, Chang LS, Birkett DH, et al. The impact of pneumoperitoneum, pneumoretroperitoneum, and gasless laparoscopy on the systemic and renal hemodynamics. J Am Coll Surg. 1995; 181: 397– 406 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McDougall EM, Monk TG, Wolf JS, Jr, et al. The effect of prolonged pneumoperitoneum on renal function in an animal model. J Am Coll Surg. 1996; 182: 317– 328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. London ET, Ho HS, Neuhaus AM, et al. Effect of intravascular volume expansion on renal function during prolonged CO2 pneumoperitoneum. Ann Surg. 2000; 231: 195– 201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Su LM, Ratner LE, Montgomery RA, et al. Laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy: trends in donor and recipient morbidity following 381 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2004; 240: 358– 363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]