Abstract

Alpha-1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency is a rare genetic disorder characterized by hepatitis in neonates, childhood and adulthood (protease inhibitor (PI)*ZZ) and emphysema with or without hepatitis (PI*ZZ)/(PI*SS,SZ or null) in adulthood. We report the case of a female neonate born at 40 weeks of gestation who presented with vitamin K deficiency-related intracranial bleeding and cholestasis of which she died at 28 days of age. At autopsy, the infant was found to have intracranial bleeding, hepatomegaly, and cholestasis with paucity of bile ducts in the liver. Small periodic acid-Schiff diastase positive intrahepatic granules and positive staining with antibodies against AAT protein suggested an AAT deficiency. AAT is a glycoprotein that has a protease inhibitor function. Its deficiency can be the result of various point mutations in Serpin 1 located on chromosome 14. The diagnosis AAT deficiency was confirmed by mutation analysis showing the PI*ZZ genotype in the neonate. In conclusion, AAT deficiency is a rare genetic disorder that can lead to a serious bleeding disorder in the neonatal period if not recognised on time. Pathological diagnosis together with verifying molecular analysis can be used to identify index patients.

Keywords: Alpha-1-antitrypsin, Death, Deficiency, Neonatal

Introduction

Alpha-1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency, an autosomal recessive disorder, is caused by inheritance of two severe deficient alleles of Serpin 1 (located on chromosome 14q31-32) encoding AAT [2]. AAT is a protease inhibitor with three β-sheets and eight α-helices. The reactive loop site in the β-sheet contains the neutrophil elastase binding site with a methionine residue [3]. The protease inhibitor (PI)*MM wild-type allele is the most prevalent normal allele and has many variants [2]. The most important pathogenic PI*S and PI*Z variants show mutations Glu264Val and Glu342Lys, respectively, whereas PI*null variant has no protein production. The patient can be homozygous or compound heterozygous for pathogenic variants. The protein product contains variable amounts of abnormal polymers of AAT molecules which retain in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in the liver. These retained abnormal polymers can lead to hepatic cell injury and result in haemorrhagic disease and or cholestasis in infancy and chronic liver disease in childhood or adulthood. In addition, the uninhibited action of the neutrophil elastase in the lungs can cause alveolar damage resulting in emphysema in adulthood [3].

The highest PI*Z variant prevalence was recorded in northern and western Europe (mean gene frequency, 0.0140) [9]. Persons with the PI*ZZ phenotype have 10–15% of normal AAT plasma levels. About 12% of ZZ infants develop neonatal hepatitis and cholestasis within the first month of life [5]. The presenting symptom in neonates can vary from harmless-looking (warning) bleeds or earlier recognised jaundice to cholestasis and full-blown bleeding diathesis with dramatic consequences [4, 6, 11].

To diagnose AAT deficiency, three different methods can be used—level testing in blood, Pi-typing (phenotyping) and genotyping. Level testing is not specific, phenotyping shows the mutated protein and genotyping detects the common selected mutations [1].

Case report and results

A 4-week-old baby girl was admitted to the neonatology department of our hospital because of respiratory insufficiency, convulsion and a large intracranial bleeding. She was the second child of healthy non-consanguineous parents born after an uneventful pregnancy and delivery at 40-weeks gestational age. Family history yielded no important diseases. Neonatal screening in the first week showed no abnormalities. Vitamin K prophylaxis was given at birth and until hospital administration according to the standard Dutch protocols [10]. From birth, she was only breastfed. Two weeks after birth, minimal rectal blood loss was noted. This was considered by the referral hospital to be due to cow milk allergy. The mother was instructed to follow a cow milk protein-free diet for herself. In the following weeks, oozing of the umbilical cord and bruising of the palate were noted. Both symptoms were reported separately and considered not to be alarming by the different general physicians. Nearly 4 weeks after birth she became lethargic, started vomiting and refused breastfeeding. She was referred to the emergency department of the referral hospital. At first, an infection was suspected for which intravenous antibiotics were started. A few hours after admission, convulsion started. Phenobarbital was administered. She became respiratory insufficient for which she was intubated, ventilated and transported to our university hospital.

We saw a pale hypotonic neonate with a bulging tense fontanel without palpable pulses. Pupils were dilated with hardly a reaction to light. Laboratory results revealed total bilirubin, 85 μmol/L; conjugated bilirubin, 58 μmol/L; ASAT, 94 U/L; ALAT, 40 U/L; haemoglobin, 4.6 mmol/L; thrombocytes, 388 × 109/L; prothrombin time (PT), >100 s and partial thromboplastin time (PTT), >300 s. Vitamin K-dependent clotting factors were all below 40%. Because factor V and factor VIII levels at the same time were 160% and 200%, respectively, clinical Vitamin K-dependent bleeding disorder (VKDBD) was suspected. Vitamin K (1 mg) was given intravenously and within 2-h PT and PTT times, factor V and factor VIII levels normalized. CT scan showed large intraventricular bleedings on both sides and a large intraparenchymal bleeding in the left temporal lobe with severe oedema. An emergency external ventricular drainage was performed. Postoperatively, there was no improvement in her clinical condition. Pupils were dilated and non-responsive. No cornea reflex could be evoked. Treatment was withdrawn, and she died 1 day after admission.

Differential diagnosis for the background pathology leading to cholestasis, liver dysfunction and further VKDBD was biliary atresia, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency, cystic fibrosis, inborn error in bile acid synthesis, haematochromatosis, liver pathology such as viral neonatal hepatitis or one of rare autosomal recessive forms of vitamin K-dependent clotting factor deficiency 1 and 2.

Pathology

Autopsy

Both parents gave informed consent for complete autopsy.

At brain autopsy, left temporal lobe showed haemorrhage with intraventricular extension. This resulted in increased intracranial pressure and herniation of the cerebellar tonsils. At body autopsy, the liver was greenish-brown showing bile staining by cholestasis. The gallbladder, the extrahepatic bile ducts and the papilla of Vater could be identified and opened. The mucosal lining showed bile staining. With these findings we excluded biliary atresia macroscopically. The new pathologic differential diagnosis for the primary source of the problems leading to VKDBD in this patient was neonatal hepatitis/viral neonatal hepatitis, haematochromatosis or AAT deficiency.

Microscopy

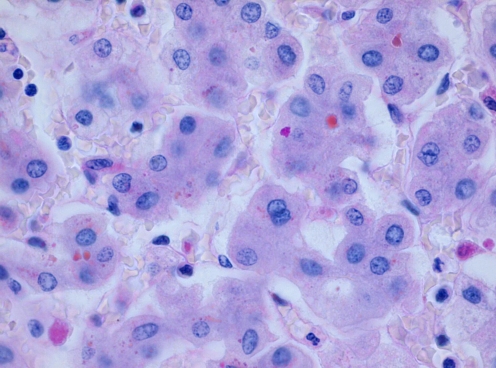

Microscopic examination of the liver displayed acute hepatitis with portal tracts showing a mixed inflammatory reaction with variable destruction of bile ducts and infiltration of the parenchyma. Slight fibrosis with septum formation was present. There was intraductal and intracanalicular cholestasis. The parenchyma showed individual hepatocyte necrosis with accumulation of waste products, bile and iron in hepatocytes and Kupfer cells. Among the waste products were fine cytoplasmic granules located especially in the periportal hepatocytes which stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) before and after diastase pretreatment (Fig. 1). These PAS (+) granules were not abundant enough to diagnose the primary pathology with certainty; however, suspicion rose on AAT deficiency.

Fig. 1.

PAS diastase positive granules in the hepatocytes. H & E, ×400

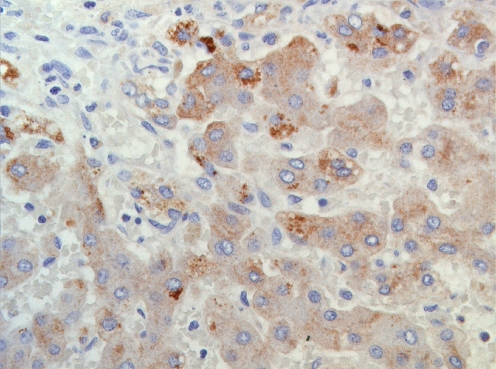

The additional immunohistochemical anti-cytokeratin 7 and anti-cytokeratin 19 stainings (Biogenex) showed focal paucity of the premature and mature bile ducts, respectively. This paucity could be due to periductal inflammation and cholestasis. Finally, anti-AAT protein staining (DAKO, concentration 1/40,000 without antigen retrieval in DAKO immunostainer) showed clearly the accumulation of AAT protein polymers in the hepatocytes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical staining showing AAT protein deposition in the hepatocyte (×200)

Microbiology

PCR studies to identify viral agents showed no cytomegalovirus in liver. Additional studies in microbiology showed no growth of bacterial of viral agents.

Molecular analysis

Genomic DNA from peripheral bloods cells was isolated according to standard procedures. Mutation analysis of Serpin 1 was performed by direct sequence analysis of the coding exons (2–5; exon 2 split into two). Primers, containing an M13 tail, used were:

| Exon 2-1 | Forward: 5′ cacttccacgtggtgtcaat |

| Reverse: 5′ ggttgagggtacggaggagt | |

| Exon 2-2 | Forward: 5′ ttcttctccccagtgagcat |

| Reverse: 5′ gaatccacgctgaaaagcat | |

| Exon 3 | Forward: 5′ ggaggggactcatggtttct |

| Reverse: 5′ tagcagtgacccagggatgt | |

| Exon 4 | Forward: 5′ tagtgtgggtggaggacaca |

| Reverse: 5′ cagcctgggtcttcatttgt | |

| Exon 5 | Forward: 5′ gtccacgtgagccttgct |

| Reverse: 5′ ggaccagctcaacccttctt |

PCR reactions were performed using standard conditions (25-μL reaction, containing 100-ng genomic DNA; 2′ at 94°C, followed by 29 cycles of 30″ at 94°C, 30″ at 60°C and 30″ at 72°C and a final extension of 10′ at 72°C).

Sequence analysis of exon 5 of Serpin 1 showed a homozygous pattern for p.Glu342Lys in our patient. In agreement with the homozygous pattern, the parents of the patient were heterozygous for this pathogenic mutation.

Discussion

Alpha-1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency has an incidence of 0.05% and can be caused by homozygosity for PI*Z [9]. The mutant Z protein can form abnormal polymers of AAT within the rough ER of hepatocytes. Chains of these polymers become interwoven to form insoluble inclusions resulting in reduced levels of this protein in the bloodstream. These inclusions form the hallmark of AAT deficiency in pathological diagnosis [8]. Clinical progression to liver disease is complex, with Z allele homozygous neonates developing hepatitis and cholestasis in about 10% of the cases [5]. Here, we reported our findings in a 4-week-old female neonate who showed harmless-looking warning bleeds at the age of 2 weeks and cascade of complications leading to her death as a result of intracranial VKDBD under standard vitamin K prophylaxis [10].

Although VKDB is described earlier as a complication of AAT deficiency in neonates, there are still two important lessons we can learn from this patient.

The clinical lesson is the importance of early recognition of the warning bleeds or the cholestasis. Various reports showed a correlation between cholestasis and VKDB due to fat malabsorption. It is also reported that adjustment of the standard vitamin K prophylaxis protocols could prevent the complications due to VKDB which also could have been the case in this patient [12].

The diagnostic lesson is to use pathology as an instrument in combination with verifying genotyping to diagnose AAT deficiency. This statement contrasts with the earlier studies where the cytoplasmic inclusions were not seen in children younger than 3 years [5, 7] or the false-positive results which can be observed with immunohistochemistry in this age group [7].

In conclusion, however, early recognition of the warning bleeds or cholestasis, correct diagnosis using pathology as a diagnostic instrument in addition to the existing methods and adjustment of the standard vitamin K prophylaxis protocols to prevent VKDB complications can be life saving in AAT deficiency patients especially in the neonatal period.

Acknowledgments

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Brantly M. Efficient and accurate approaches to the laboratory diagnosis of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency: the promise of early diagnosis and intervention. Clin Chem. 2006;52:2180–2181. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.078907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brantly M, Nukiwa T, Crystal RG. Molecular basis of alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Am J Med. 1988;84(Suppl. 6A):13–31. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fregonese L, Stolk J. Hereditary alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency and its clinical consequenties. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hope PL, Hall MA, Millward-Sadler GH, Normand ICS. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency presenting as a bleeding diathesis in the newborn. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57:68–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutchinson DCS. Natural history of alpha-1-protease inhibitor deficiency. Am J Med. 1988;84(Suppl 6A):3–12. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Israels SJ, Gilfix BM. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency with fatal intracranial hemorrhage in a newborn. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;21(5):447–450. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jevon GP, Dimmick JE. Histopathologic approach to metabolic liver disease: part 1. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 1998;1:179–199. doi: 10.1007/s100249900026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lomas DA, Evans DL, Finch JT, Carrell RW. The mechanism of Z alpha-1-antitrypsin accumulation in the liver. Nature. 1992;357(6379):605–607. doi: 10.1038/357605a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luisetti M, Seersholm N. α1-Antitrypsin deficiency. 1: Epidemiology of α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Thorax. 2004;59:164–169. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.006494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uitentuis J. Administration of vitamin K to neonates and infants. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1990;134:1642-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van der Anker JN, Sinaasappel M. Bleeding as presenting symptom of cholestasis. J Perinatol. 1993;13(4):322–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Hasselt PM, Kok K, Vorselaars AD, et al. Vitamin K deficiency bleeding in cholestatic infants with alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94:F456–F460. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.148239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]