Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Genital endometriosis is still an unclear enigma of the female. It occurs in approximately 20% to 35% of all women of reproductive age. The urinary tract is seldom affected.

Methods:

We report on a patient with bladder endometriosis with recurrent heavy pain at menstruation within the framework of 5 similar cases.

Results:

A combined vaginal and laparoscopic treatment with excision of the lesion reaching into the dome of the bladder and vaginal wall was performed. The bladder opening was sutured in 2 layers.

Conclusion:

Laparoscopic treatment of bladder endometriosis requires a combined surgical treatment by a gynecologist and urologist or an experienced laparoscopist.

Keywords: Bladder endometriosis, Laparoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Endometriosis is a common benign gynecological disease characterized by the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue outside the uterus. It is a well-known fact that endometriosis most commonly affects such organs as the ovaries, utero-sacral ligaments, uterine tubes, pouch of Douglas, and rectum. Ureters are sometimes stenosed by the growth of endometriotic tissue around them. The bladder, however, is an infrequent site of endometriosis localization, and it is estimated that only 1% of patients suffering from this disease have lesions involving the urinary system.1 Fewer than 200 cases of bladder endometriosis have been described in the literature.

Three leading theories explain the origin of bladder endometriosis:

It develops from müllerian remnants in the vesicouterine/vesicovaginal septum.

It is in fact an extension of an adenomyotic nodule of the anterior uterine wall.

It results from implantation of regurgitated endometrium.2

METHODS

From January 2003 to October 2006, six patients with bladder endometriosis were treated at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospitals Schleswig- Holstein, Campus Kiel. The patients were between 30 and 40 years of age. The symptoms varied from dysmenorrhoea, cystitis, and pain in the abdomen to menorrhagia. In 2 cases, endometriosis of the bladder was an accidental finding in a diagnostic pelviscopy performed for primary sterility. The EEC classification was grade IV in 2 cases and grade II in 4 cases.1

Transvaginal sonography was performed in all 6 patients and cystoscopy in 2 patients.

Associated endometriotic lesions involving the ovaries and pouch of Douglas were seen in 5 patients. One patient had associated fibroids of the uterus. Another patient experienced urethral dilation 3 years prior to laparoscopic treatment of endometriosis, and a third patient underwent laparoscopic bilateral endometrioma enucleation.

Of 6 patients, 2 with recurrent cystitis, menstrual hematuria, and lower abdominal pain underwent laparoscopic resection of the bladder wall, followed by suturing of the bladder defect with 4–0 PDS in 2 layers. Four patients underwent coagulation of the endometriotic foci over the uterovesicular peritoneum. One of these patients had been treated with GNRH analogues for 3 months for an associated fibroid.

Associated endometriotic lesions were treated in 5 patients, treatments including adhesiolysis and myoma enucleation in one patient. Symptomatic relief of hematuria, recurrent cystitis, and abdominal pain was seen in all patients. After these treatments, all patients were without pain and reported none of the previous symptoms. In the following report, one case is described in detail.

CASE REPORT

A 38-year-old lady presented with pain in the lower abdomen in a 4-week rhythm although the uterus had been previously resected. She also suffered from pain while urinating, menstrual hematuria, and hypermenorrhea every 3 weeks to 4 weeks. Symptoms started after the second vaginal birth in 1998; a cystoscopy was without pathological findings. The patient underwent a pelviscopy in 2001 for suspected endometriosis and adhesions and a vaginal cystectomy in 2003.

At the vaginal examination in 2005, a walnut-sized nodule at the top of the anterior vaginal wall could be touched, which was painful at compression. We recommended transvaginal excision to remove the nodule and to detach the endometriotic lesions, followed by operative laparoscopy.

The surgery was performed with the patient in a dorsosacral position. The nodule in the anterior vaginal wall was palpated in the septum vesico-vaginale. The induration was grasped, excised in toto, and sent for histological clarification. The wound was closed with simple interrupted sutures. The pelviscopy was begun by insufflation of 3.6 liters of CO2 and positioning of 3 trocars; the optic trocar in the caudal umbilicus and two 5-mm trocars in the right and left lower abdomen.

The diagnostic laparoscopy and pelviscopy revealed no adhesions in the upper and mid abdomen, no uterus, an appendix without signs of irritation, a right ovary of normal size, and a left ovary partially adherent to the pelvic wall. On the right twisted tube, we discovered a 1-cm pedicled hydatid that was displaced by coagulation at the pedicle and sent for histological clarification. In the pouch of Douglas on the dorsal right, we found 2 endometriotic lesions that were thermocoagulated.

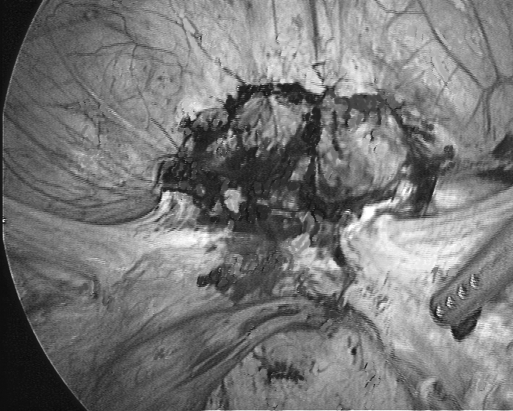

The main manifestation of endometriosis was found in the dome of the bladder, appearing as endometriosis extragenitalis, EEC IV°.1 The peritoneum over the bladder was star-like inserted; the center of the lesion was brown and white colored. The lesion appeared as a 2 × 3-cm large nodule infiltrating into the bladder wall (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

2 × 3-cm endometriotic bladder lesion.

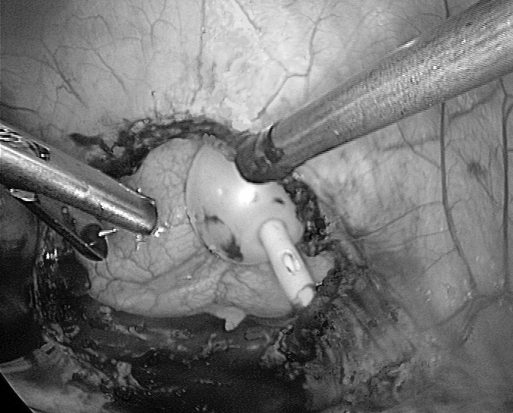

The gynecologist and urologist cooperated to excise the nodule circularly from the peritoneum with the hook scissors, mobilized on the level of the muscular bladder wall and removed completely with the simultaneous excision of a 2 × 2.5-cm large adherent lobe of urothelium off the bladder wall. This resulted in an unobstructed view into the bladder with clean, smooth, and bloodless wound edges (Figure 2). To reduce the tension at the margins of the wound, we laid an extracorporal, knotted PDS size 0 suture through all layers of the bladder.

Figure 2.

View into the urinary bladder after complete laparoscopic resection of an endometriotic nodule.

At the right and left wound slot, the urothelium was closed completely with an intracorporal, knotted PDS size 4 suture. For the second layer, we laid an extracorporal, knotted PDS size 0 suture in the middle of the wound to place the peritoneum of the bladder over the wound. On the right and left side, we closed the peritoneum permanently over the wound of the bladder with simple interrupted sutures, size 4–0.

To check the closure, we filled the bladder with 80 mL to 100 mL of blue solution and no leakage occurred. After irrigation of the abdominal cavity and placing of a 5-mm Robinson drainage for 24 hours, we removed the trocars under vision and closed the skin incisions. The operation time was 3 hours 20 minutes. The patient received a bladder catheter and antibiotics for 10 days. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged after 48 hours. Three weeks after the operation, a cystoscopy with contrast medium was performed without pathological findings, and the patient reported no pain. At a control examination 15 months later, the patient was still pain free.

DISCUSSION

Broadly speaking, vesical endometriosis has 2 different causes: a primary and a secondary form. The primary form is a spontaneously occurring manifestation of a generalized pelvic disease. The secondary form is iatrogenic, occurring after pelvic surgery, such as cesarean delivery or hysterectomy.3,4 After iatrogenic dissemination, growth of ectopic endometrium is usually limited to the bladder wall.

Symptoms, when present, mimic those of recurrent cystitis, or more rarely the condition is characterized by pathognomic menstrual hematuria.1,2 Early diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract endometriosis is necessary to avoid loss of kidney function.5

Various diagnostic modalities are used in preoperative assessment of bladder endometriosis. Transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound are the initial investigation of choice in evaluation of suspected bladder endometriosis due to immediate availability and easy access. It has proved adequate in determining the site and size of lesion, the degree of infiltration of detrusor and mucosa, and the relationship with concomitant adenomyosis of the uterus.6,7

Magnetic resonance imaging can not only delineate the morphologic abnormalities of bladder endometriosis but can also potentially identify other common sites, particularly at the uterosacral ligaments, where ultrasound is less reliable.8 Cystoscopy is able to visualize the endometriosis foci only when present on bladder mucosal surface, but is unable to define the extent of endometriosis lesion, which can be better detected by TV sonography.

Treatment varies according to severity and site of involvement of each case. Hormonal therapy is a reasonable and effective management for bladder endometriosis reaching into the genital tract. Because it preserves fertility, it is especially attractive to younger women. However, experienced laparoscopists, familiar with endometriosis, can also treat urogenital endometriosis safely and effectively using excision. Segmented resection may be performed, or transurethral resection of the bladder mass, and ureterolysis, if necessary.

In cases of submucosal transmural location of the lesion, a minimally invasive combined endoscopic procedure (laparoscopy and cystoscopy) represents a good alternative to partial cystectomy for muscle infiltrating bladder endometriosis that does not involve the vesical mucosa.

CONCLUSION

Bladder endometriosis should be considered in women of reproductive age who present with urinary tract symptoms not responding to routine medical management with a view to laparoscopic treatment. An optimal treatment of bladder and urethral endometriosis should ideally involve a team of experts, ie, gynecological endoscopists, radiologists, and urologists, who are familiar with endometriosis.

References:

- 1.Mettler L. Manual for Laparoscopic and Hysteroscopic Gynecological Surgery. New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vercellini P, Frontino G, Pisacreta A, De Giorgi O, Cattaneo M, Crosignani PG. The pathogenesis of bladder endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:538–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal N, Kriplani A. Intramural bladder endometriosis after caesarean section: diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. J Gynecol Surg. 2002;18:69–73 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mettler L. Manual of New Hysterectomy Techniques. New Delhi, India: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komar PD. Urinary tract endometriosis. Ind J Surg. 2004;66:41–43 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seracchioli R, Mannini D. Cystoscopy - assisted laparoscopic resection of extramural bladder endometriosis. J Endourol. 2002;16:663–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaty SD, Silva AC, de Petris G. Bladder endometriosis: ultrasound and MRI findings. Radiology Case Reports. 2006;1:92–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fedele L, Bianchi S. Pre-operative assessment of bladder endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 1997;11:2519–2522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]