Abstract

In spite of widespread support from most member countries’ societies for European Union policy, including support for the sustainable development idea, in many EU countries the levels of acceptance of new environmental protection programmes have been and, in particular in new member states, still are considerably low. The experience of the countries which were the first to implement union directives show that they cannot be effectively applied without widespread public participation. The goal of this study was, using the example of Poland, to assess public acceptance of the expansion of nature conservation in the context of sustainable development principles and to discover whether existing nature governance should be modified when establishing new protected areas. The increase in protected areas in Poland has become a hotbed of numerous conflicts. In spite of the generally favourable attitudes to nature which Polish people generally have, Natura 2000 is perceived as an unnecessary additional conservation tool. Both local authorities and communities residing in the Natura areas think that the programme is a hindrance, rather than a help in the economic development of municipalities or regions, as was initially supposed. This lack of acceptance results from many factors, mainly social, historic and economic. The implications of these findings for current approach to the nature governance in Poland are discussed.

Keywords: Conflict management, Natura 2000, Nature conservation, Public participation, Sustainable development

Introduction

European Nature Conservation Policy: Current Trends

Accession to the European Union (EU) offered extensive opportunities for development and changes in policy of individual countries in practically all sectors of the economy. A consequence of membership in the EU was the implementation of standards of Union law including a broad spectrum of principles of sustainable development (Larobina 2001). In the case of nature conservation, the European policy distinctly strengthened the implementation of the sustainable development strategy through the requirement that member countries have to adopt international commitments, chiefly the Convention on Biological Diversity and the resulting expansion of nature conservation areas. Of special importance in this regard are the provisions resulting from EU directives: the Birds and the Habitats Directive. Pursuant to the requirements of the Habitat Directive, a new form of nature conservation—the Natura 2000 European Ecological Network—has been created in the territory of the EU (International Union for Conservation of Nature 2005).

Legal protection of natural resources in majority of the EU Member States is currently provided by legislation protecting individual species and areas. In Poland, for example, they take the form of national parks, nature reserves, nature, landscape parks and areas of landscapes parks. These systems seem to be an effective tool for the protection of natural resources at the national level of each country (Symonides 2008). On a continental scale the nature conservation policy requires the adoption of a wider and operational perspective. Nowadays at the enlarged EU level however, the goals, general principles and the implementation of the nature conservation policy have become more complex and multi-level, eventually resulting in top-down governance. Such an attitude is inherently at risk of being introduced locally with a low level of effectiveness and adaptability (Folke and others 2007). That is why current trends in managing nature (mainly biodiversity) protection in the EU, in addition to recommending the means of implementing actions imposed in a top-down fashion, are increasingly often perceived as needing to be complemented with significantly more effective bottom-up initiatives. The latter appear to be essential, particularly in the new Member States where nature conservation is still often affected by the post-socialistic governance type and thus operates in a rather ineffective way (Kluvánková-Oravská and others 2009).

The key issue, as shown by practices already in use mainly in EU-25 countries which were the first to introduce the new nature conservation policy seems to be to involve the widest possible group of actors (non-governmental organizations, community members, etc.) at various, particularly local levels (Paavola and others 2009; Silva and others 2009). Public participation is explicitly mentioned as a means and goal of sustainable development in EU strategies (Commission of the European Communities 2005). In the case of nature and environmental conservation it is defined in the provisions of the Habitat Directive and the Convention on access to information, public participation in decision-making and access to justice in environmental matters, commonly known as the Conventions of Aarhus (Dz. U. 2003, No 78, item 706; Koester 2007; Stec and others 2000). According to both these documents, public participation should manifest itself in society’s access to information about the natural environment and its involvement in successive stages of the implementation of protective measures: from planning to making decisions in management. Public participation is consistent with the three-dimensional concept of sustainable development as it allows natural capital to be traded off for economic and social capital. That is why the difficulty of involving the public in the execution of nature conservation tasks illustrates the more general problems associated with the implementation of sustainable development principles (Palerm 2006). In addition to increasing acceptance for a new policy itself, public participation in environmental protection has a broader significance, as it leads to the development of multilevel governance, encompassing the wider—interdisciplinary—context, the introduction a number of new structures and financial resources to the civil society of a country (Antoniewicz 2006; McCauley 2008).

The goal of this study was to (1) assess public acceptance of the extension of nature conservation in the context of sustainable development principles and (2) examine whether it is necessary to modify the current governance system to a more multi-level and participatory approach. The study covered local communities and the local governments of Polish municipalities located in protected areas: the former with regard to land ownership issues, and the latter with respect to the need to include European and Polish guidelines of nature protection policy in municipal plans for the physical development of their municipalities and regions. In particular, the interest in this study focused on:

Whether the expansion of nature conservation caused by the introduction of Natura 2000 European Ecological Network is a source of potential social conflicts observed at the local level among various actors—government and community? If so, what are the reasons and how do they differ between the two groups involved?

How do residents of newly established protected areas and their surroundings perceive the need for nature conservation in the context of infrastructure development and private business investment in their regions?

Is the effectiveness of Natura 2000 implementation affected by the current nature conservation policy?

Do opinions and problems associated with the establishment of new protected areas vary among municipalities and regions? If so, what factors differentiate them?

The Natura 2000 European Ecological Network: Theory and Practice

The Natura 2000 programme is of great practical importance for the implementation of the sustainable development strategy, mainly due to its firm legal basis (including the possibility of national decisions to be revised by the European Commission), the scale of this undertaking and the principles of the nature conservation system itself (Ostermann 1998). The latter considerably differ from the previous traditional European system, that is, going beyond a direct ban on damaging plants or killing animals. The main effect of the programme’s introduction is to reconcile nature conservation with features of sustainable development, namely a possibility of working out a compromise between economic development and rational use of natural resources. Particularly significant for the functioning of the programme is the introduction of the criterion of the overriding public interest which should also include future generations, as well as levelling the existing economic differences between European Community countries (Oana 2006; Unnerstall 2006).

Generally, European nature conservation policy and the resulting necessity to implement new programmes, e.g., Natura 2000, has led to dissatisfaction and relatively low acceptance levels with regard to the solutions proposed (Beaufoy 1998; European Commission 2004; Julien 2000). In many countries, including Poland, this was due to many factors, the main ones being no tradition of the public participation approach, the ownership structure of the land brought into protected areas and the funding of the programmes (Bland and Thiry 2003; de Piérola and others 2009; Perzanowska and Grzegorczyk 2009; Weber and Christophersen 2002).

Although the methods of implementation of Natura 2000 programme are defined by legislation and there is a possibility of benefiting from the experience of older EU Member States, in many countries the programme’s implementation encountered considerable difficulties. This was caused by both the centralised character of the programme and the public participation requirements being too vaguely defined by the Habitat Directive (Beunen 2006). In central and eastern Europe implementation difficulties were additionally caused by a weak history of participatory governance, including the absence of a collective choice mechanism, lack of a conflict management system, undefined responsibility for the coordination of resources and very limited experience in acquiring EU funding for the programme’s implementation which were simply not available at the national level (International Union for Conservation of Nature 2005). In the almost all EU countries, dissatisfaction was noticed at various stages of the programme’s implementation, particularly designation of the site boundaries and recommendations to be taken into account in preparing management plans (Dimitrakopoulos and others 2004; Visser and others 2007). In the majority of the EU Member States, the sites were designated practically only on the basis of environmental considerations whereas a very limited number of consultations with local governments, decision-makers and land owners were conducted (Małopolski Urząd Wojewódzki 2008; Makomaska-Juchiewicz 2007). This has additionally confirmed local governments in their opinion that the initiative itself is centralised in character—not properly adapted to specific local conditions, and consequently discouraged them from becoming involved in it (Cash and others 2006).

The land use structure in the Natura 2000 areas features a high proportion (varying between the regions and countries) of private land, hence it is managed by their owners—chiefly farmers (Makomaska-Juchiewicz and Tworek 2003; Soma 2009). This, in turn has a definite negative traditional and historical connotation. Many owners of arable land or forests took Natura 2000 to be an initiative infringing their basic property rights (Hiedenpää 2002). The designation of protected areas especially in the case of post-socialist countries such as Poland, is still associated with the post-war incorporating of private land to establish national parks, which involved a loss or the obligation to sell private properties for outlandishly low prices (Królikowska 2007; Partyka and Żółciak 2005). Thus far, within Natura 2000 no attractive compensation programme for the owners of private land that is included in the network has been developed. Only some countries, like France, managed to resolve these issues although late and only when forced by the need to ease conflicts (Alphandery and Fortier 2001; McCauley 2008). Activities developed and completed in the EU are however a far cry from the well prospering system of financial compensation that has been in operation in the USA for a long time (Fischer and others 2009; Wallace and others 2008).

To sum up, it can be assumed that many EU countries already completed two first stages of the Natura 2000 Programme by establishing the list of protected areas and developing the management plans for each of the site. Finally, Natura 2000 sites cover around 20% of the continent surface varying among the countries from 7.1% in the UK, 12.8% in Germany, 20.9% in Portugal, 21% in Poland to as much as 34.9% in Bulgaria or 35.5% in Slovenia (Ministry of the Environment Poland 2009, http://natura2000.mos.gov.pl). In the case of Poland, the sites’ list is currently being assessed and verified by the European Commission. The country enters the next stage of the programme—preparation of the management plans for individual sites. This, as in other EU countries, will probably result in arising various conflicts, particularly at the local level (Young and others 2005).

Materials and Methods

The Study Area

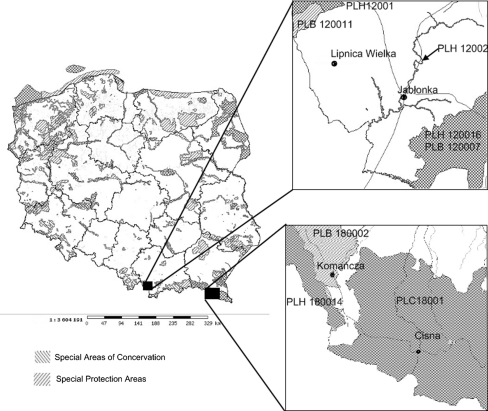

This study includes (1) a content analysis of comments made by representatives of municipalities included in the programme in terms of justifications of the boundaries of the Natura 2000 sites and (2) face to face questionnaire surveys of residents of selected municipalities. Comments made by representatives of municipalities were obtained for analysis from the Institute of Nature Conservation of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Krakow. The surveys were conducted in 4 municipalities (Jabłonka, LipnicaWielka, Cisna, Komańcza) which were partly included in seven habitat (SACs) and bird (SPAs) sites (PLB120007, PLH120016, PLB120011, PLH120001, PLH120012, PLH120002, PLC180001) of the alpine bioregion encompassing the Carpathians. The Jabłonka and LipnicaWielka are located in the Orawa Region, whereas the Komańcza and Cisna municipalities are located in the Bieszczady Mountains (Ministry of Environmental Protection Poland 2009, http://www.natura2000.mos.gov.pl) (Fig. 1). These are all the regions with a well-established conservation tradition, but they differ considerably in terms of their land use patterns, population and labour market. Orawa is wealthier than the Bieszczady region, oriented mainly at tourism and burdened by historic connotations of introducing new forms of nature conservation. It was here that mainly in the post 2nd World War communist period land was taken—or bought for a token price—to become later incorporated into national parks that were created at that time. On the other hand, Bieszczady is one of the least populated regions in Poland, with shorter conservation traditions than Orawa (Andrzejewski and Weigle 2003; Central Statistical Office Poland 2009, http://www.stat.gov.pl) (Table 1). Focussing the study on the alpine bioregion was justified by the fact that the scope of consultation on the final shape of the Natura 2000 network was more advanced in this region than in the continental bioregion covering the rest of Poland (Fig. 1). The Natura sites selected are so diversified in terms of the land use and character of the habitats that the scope of problems and potential conflicts associated with the Natura 2000 programme in these areas was considered to be representative of the whole network. Also, representatives of alpine municipalities were more critical in their assessment of the site boundaries, thus one can expect that conflicts in these areas are more likely.

Fig. 1.

Areas of the study

Table 1.

Description of the municipalities studied and the areas of protected nature within their boundaries

| Name of the municipality | Lipnica Wielka | Jabłonka | Cisna | Komańcza |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Orawa | Orawa | Bieszczady | Bieszczady |

| Province | Małopolskie | Malopolskie | Podkarpackie | Podkarpackie |

| Nature area | Babia Góra (PLB120011; PLH120001) |

Czarna Orawa (PLH120002) Orawa and Nowy Targ Peat Bogs (PLB120007; PLH120016) |

Bieszczady (PLC180001) | Bieszczady (PLC180001) |

| Population | 5,685 | 17,031 | 1,679 | 5,134 |

| Area | 67.5 km² (49% farm & 48% forest use) | 213.28 km² | 286.89 km², (5% farm & 87% forest use) | 455.18 km² (23% farm & 69% forest use) |

| (60% farm & 34% forest use) | ||||

| Unemployment rate (%) | 4.10 | 4.50 | 18.10 | 7.40 |

| Environmental description of the Natura 2000 site |

18 types of habitats with forest communities & high mountain grassland; dwarf mountain pine; 924 vascular plants species (rare, threatened or already protected), rich (ca. 2500 species) invertebrate fauna; very important area for birds; Threats to the area: transfrontier air pollution, dumping of waste from homesteads |

Czarna Orawa A need to protect rare fish species habitats; one of two in Poland natural sites of the Danube salmon; important vegetation on the streams embankments, riparian forests; Threats to the area: sewage, collection of stones & gravel from the stream bed Orawa-Nowy Targ Peat Bog Valuable peat bogs, marsh forests, meadows & riparian habitats; The most important habitats: Myricaria & willow thicket on the stony embankments of streams, high peat bogs, marshy coniferous forests & riparian forests; rich fauna: bears, wolves, otters, Yellow-bellied toads, Great Crested Newts & Carpathian Newts. Threats to the peat: General lack of water, illegal extraction by locals, water pollution & drainage. Plans to build a sewage treatment plant. |

29 protected species & 21 types of habitats; 1100 vascular plant species (many rare, threatened & legally protected); valuable forest communities, e.i. Carpathian beech, sycamore & unique to Poland mountain pasture communities. 38 bird species named in the Directive & 13 in the Polish Red Book; Important terrain for nesting (ca. 150 species) & hatching (area occupied by 1% of the national population of many important species, i.e.: the black stork, the White-backed woodpecker, Lesser Spotted Eagle, Golden Eagle, Eagle Owl); rich forest fauna: bears, wolves, lynxes; strong populations of otters, the Aeskulapian snake. |

|

| Other forms of nature protection within the municipality (date of creation) | Babia Góra National Park (1954) and the Babia Góra Biosphere reserve (1977) | Bieszczadzki National Park (1973) | ||

| San Valley Landscape Park (1992) | ||||

| “Bembeńskie” Forest Reserve (2001) | Transborder Part of the Biosphere Reserve Eastern Carpathians (1992) | |||

| “Na Policy” Reserve (1972) | Cisna-Wetlina Landscape Park (1992) | |||

| The whole municipality is a Protected landscape Area* | Sine Wiry Reserve (1988r.) | Jaśliski Landscape Park (1992); | ||

| “Olszyna łęgowa w Kalnicy” Reserve (1971) | “Zwięzło” Reserve- Duszatyn Lakes (1957); “Przełom Osławy pod Duszatynem” Reserve (2000) | |||

Methodology of the Study

Analysis of documents covered remarks made by 233 representatives from local governments of municipalities where Natura 2000 was introduced. Remarks were formulated in the form of answers to the official request from the Minister of the Environment to express their opinion on the submitted proposals for the site boundaries. The contents of the remarks were coded with the QDAMiner software. Two lists with codes were used. The first one pertained to the general character of the opinions expressed, the second list included problem issues. Data concerning local governments’ opinions is presented here in accordance to alpine and continental bioregion.

The surveys were conducted on a random sample of 606 households of four selected municipalities of the alpine region. The municipalities were selected so as to represent to the fullest possible extent the potential conflicts and conditions, resulting from the introduction of the Natura2000 programme. This selection was dictated by the previous analysis of the municipalities’ opinions, press and official information on the planned projects and emerging conflicts. The households were selected using simple random sampling on the basis of address lists obtained from individual municipality offices. Within a household, respondents were selected on a quota basis, so that the sample corresponded to the municipality demographic structure in terms of age and sex. Because of the huge economic emigration from these areas (mainly men), such a method ensured that all groups of municipality residents would be well represented. The questionnaire surveys were conducted from December 2007 to January 2008. In order to inform inhabitants of aims of such an action, it was announced on the municipality office information boards and in the local catholic parishes. The survey response rate obtained was 65%.

The questionnaire used to conduct the survey was developed on the basis of semi-structured interviews conducted earlier with representatives of local governments of the municipalities surveyed, and on the basis of consultations with experts. The answers were evaluated using 5-grade scales concerning (1) the meaning of nature for people living in a given area, (2) the evaluation of potential projects in terms of their harmful effect on nature and how strongly they are desired by the respondent, (3) an evaluation of the burden of the existing forms of environmental protection, and also a part concerning (4) the respondent’s activity and occupation, (5) knowledge of the existence of the Natura 2000 programme.

The results of the questionnaire were analysed using SPSS software. Factor analysis was employed to discover the structure of attitudes to nature protection and the expansion of nature conservation areas. Groups were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test, and basic descriptions were made using averages and frequencies to questionnaire questions.

Results

Local Governments’ Attitudes Toward the Expansion of Nature Conservation Areas

In spite of the well-established nature conservation in Poland, the introduction of new forms of conservation mostly involves social resistance. In the case of Natura 2000, opposition was expressed mainly by the local governments of those municipalities where new protected areas were designated. Analysis of their comments shows negative opinions with regard to both the very idea of the programme and the need to introduce it in Poland. Members of local government identify numerous problems that, in their opinion, might occur in subsequent phases of the Natura 2000 introduction. Those most often mentioned are of economic nature, including mainly: (a) those concerning restrictions on various types of economic development (e.g. tourism, enterprise, general rise in costs) and (b) those referring to infrastructure development (e.g. tourism, roads). Another, in the order of frequency, is the group of arguments showing a possible occurrence of conflicts associated with existing physical development plans, including conflicts concerning only nature (e.g., the sufficiency of the current nature conservation system) or procedural matters. Among other, less often mentioned problems, one should bring up those referring to existing social issues which will intensify after the programme has been introduced and those regarding the municipalities’ sustainable development plans. The significance of individual comments varies among municipalities and regions. Particularly significant are the differences concerning threats to the development of tourism (Table 2). In analysing the remarks made by the municipalities, their geographic locations were taken into account: whether they are in alpine or continental regions. The analysis showed considerable differences in opinions, which can be attributed to the land ownership structure in those two regions. Historically, the alpine region was not subjected to such strong nationalisation as the rest of the country. That is why land on those areas is mostly private and thus more fragmented than in the continental region.

Table 2.

Local governments’ opinions about the proposed Natura 2000 sites. Assessment of the sites and categories of arguments. Table presents % of the municipalities

| Continental local governments (%) | Alpine local governments (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Opinions on the proposed areas: | ||

| Positive opinion | 19 | 20 |

| Negative opinion | 42 | 64 |

| Request to alter borders | 14 | 8 |

| Neutral opinion / no comment | 17 | 7 |

| No comment possible on the basis of provided materials | 9 | 0 |

| Conflicts indicated: (total) | 34 | 39 |

| On the basis of ownership of the areas | 5 | 8 |

| On the development of infrastructure | 7 | 8 |

| On actual and planned businesses | 8 | 15 |

| On building extensions | 14 | 8 |

| Types of arguments given: | ||

| (a) Economic, including: | 51 | 59 |

| extension of procedures and rise in costs | 11 | 18 |

| procedural inconsistencies | 3 | – |

| restricting the development of tourism | 11 | 23 |

| restricting the development of enterprise, encompassing industrial land (e.g. mines) | 15 | 13 |

| hindering and restricting the development of agriculture | 8 | 5 |

| hindering and restricting the development of fishing | 3 | – |

| (b) Relating to the development of infrastructure, including: (total) | 36 | 56 |

| Energy | 3 | 3 |

| Roads | 10 | 10 |

| Flood defence | 9 | 5 |

| Tourism | 8 | 33 |

| Sewage systems | 6 | 5 |

| (c) Conflicts indicated with existing development plans: | 24 | 41 |

| (d) Environmental, including: (total) | 20 | 30 |

| indicating the non-occurrence of given species and habitats | 8 | 10 |

| current protection is sufficient | 11 | 15 |

| imposing the sites will cause problems | 1 | 5 |

| (e) Procedural, including: (total) | 21 | 26 |

| lack of agreement with the local governments | 4 | 8 |

| lack of agreement with local naturalists | 3 | 5 |

| erroneously mapped out / on incorrect maps and templates | 14 | 13 |

| (f) Social (unemployment, migration of young people, impoverishment of society): | 12 | 18 |

| (g) Conflicts indicated with existing development plans for the sustainable development of the municipality | 8 | 21 |

Is Nature Conservation an Obstacle to the Economic Development of Municipalities and Regions?

Poland is classified among the group of countries of high-level economic development (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2009, http://www.hdr.undp.org/en/statistics). In practice, when compared to other EU countries, this status means, among other things, a poorly developed road network, high urbanisation rate and problems with the restructuring of agriculture. Improvement in these areas can lead to conflicts with nature conservation, especially in the cases of EU-financed projects.

In questioning the reasons for establishing Natura 2000 sites in their municipalities, local governments often used arguments referring to the overriding importance of public interest in local infrastructure development as opposed to the need to conserve local nature. These opinions opposed to in the survey studies conducted among residents of individual municipalities.

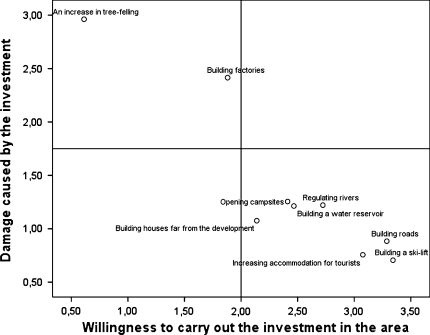

For each project the respondents (Fig. 2) were asked two separate questions, to assess on a 5-grade scale, to what extent the project would be, in their opinion, harmful to the surrounding environment and whether they wanted such a project to be implemented in their municipality. The points on the graph represent the average values of the responses. The residents of municipalities definitely prioritize the new investment projects involving the construction of new ski lifts, local roads and the increase in accommodation facilities for tourists. They think these projects do relatively little harm to local nature. The most harmful to the environment is, in their opinion, increased logging, which they do not want to occur in their areas.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between the residents’ willingness to implement the project in the municipalities and its perception as harmful for the neighbouring nature. The answers were graded on a scale of 0–4

Possible restrictions associated with the designation of Natura 2000 sites pertain not only to public infrastructure projects or to major companies, but also to small projects undertaken by individuals. That is why it seemed expedient to analyse the residents’ individual investment plans, the more so that, according to local governments the hindering of these investment tasks is and will be a source of dissatisfaction and consequent unpopularity of the Natura 2000 programme.

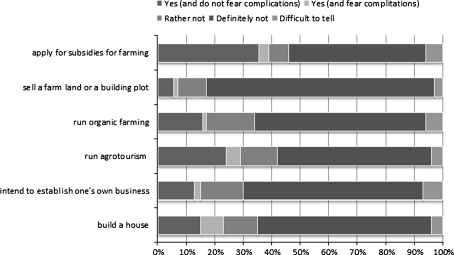

As declared by the respondents, 15% of surveyed residents plan to build their house(s) within 5 years, and the same proportion intend to start their own business (Fig. 3). This business activity may be of a varied character. More than one third of those surveyed (39%) intend to apply for subsidies for their farming under agricultural and environmental programmes subsidised by the EU Commissions, to which owners of at least 1 hectare of arable land are eligible. A smaller proportion of respondents (29%) plan to establish and run agrotourism, 17% plan to take to organic farming, whereas only 7% intend to sell their farm land or building plot located on the Natura site.

Fig. 3.

Planned projects and actions to be undertaken by residents of surveyed municipalities in the next five years. Figure indicates whether Natura 2000 implementation might cause, in the opinion of the respondents, complications to the completion of their projects and actions

Among the respondents who are planning projects, their anxiety concerning the introduction of Natura 2000 is to the highest degree shared by those intending to build a house (Fig. 3). As many as every third respondent planning such a project is concerned that Natura 2000 may make it difficult. Such fears were also shared by every fifth respondent planning to sell his plot (22% of all those planning to sell their plots). Relatively considerable anxiety is also noted among those currently running agrotourism or planning to do so: 17% of them fear that their plans will become too complicated to carry out because of the introduction of new protected areas. The intensity of this anxiety depends on the municipality and the differences observed are statistically significant, namely for building a house (χ2 = 23.979, P < 0.005), running an agrotourism business (χ2 = 11.722, P < 0.05) and selling the land (χ2 = 12.586, P < 0.05) (Table 3). Difficulties in the building of houses are feared primarily by residents of Cisna and least by residents of Jabłonka (accordingly 56 and 7% of the municipality population are planning home construction). In the case of agrotourism, the relationship is similar. As many as 26% of residents who plan running agrotourism think that Natura 2000 will hinder the implementation of their plans. Residents of Orawa are definitely less sceptical in this respect: only about 4.5% of those willing to start agrotourism business feel threatened by the new nature conservation.

Table 3.

Assessment of the statistical significance of the differences between municipalities in answering the analysed questions, using the Kruskal–Wallis test

| Variables | Chi-square | Df | Asymptotic significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do they plan to build a house | 7.907 | 3 | 0.048 |

| Do they plan to start a business | 25.322 | 3 | 0.000** |

| Do they plan to run an agrotourism business | 57.941 | 3 | 0.000** |

| Do they plan to farm organically | 9.038 | 3 | 0.029* |

| Do they plan to sell the land | 4.372 | 3 | 0.224 |

| Do they plan to apply for a farming subsidy | 28.545 | 3 | 0.000** |

| Natura 2000 will make it difficult to build a house | 23.979 | 3 | 0.000** |

| Natura 2000 will make it difficult to start a business | 4.442 | 3 | 0.218 |

| Natura 2000 will make it difficult to run an agrotourism business | 11.722 | 3 | 0.008* |

| Natura 2000 will make it difficult to farm organically | 1.869 | 3 | 0.600 |

| Natura 2000 will make it difficult to sell the land | 12.586 | 3 | 0.006* |

| Natura 2000 will make it difficult to apply for a farming subsidy | 3.822 | 3 | 0.281 |

| Does the national park make life difficult for people here | 26.770 | 3 | 0.000** |

| Is it important that the municipality has been included in the European network | 12.106 | 3 | 0.007* |

| Is it worth extending the sites of protected nature in the area | 7.875 | 3 | 0.049* |

| Is it also important to protect nature outside of the national park | 24.688 | 3 | 0.000** |

| Would they vote for a candidate planning to extend the area of protected nature | 6.852 | 3 | 0.077 |

| Should the owners of the land decide themselves about the nature on their land? | 22.745 | 3 | 0.000** |

| Do organisations that protect nature disadvantage the residents | 16.575 | 3 | 0.001** |

| Would the town/village develop faster without the national park | 30.098 | 3 | 0.000** |

* P < 0.05; ** P < 0.005

The attitude of residents from the studied municipalities to nature conservation and the extension of protected areas was analysed using the factorial method. The proposed model explains altogether 53% of variance and the KMO is 0.76. Two clear and easy to interpret dimensions were identified (Table 4).

Table 4.

Rotated factor matrix in the factor analysis conducted

| Components | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1—nature conservation hinders development | 2—it is worth extending the protected areas | |

| The national parks makes life difficult for people here | .773 | |

| Organisations protecting nature disadvantage residents | .723 | |

| Without the national park the town/village would develop faster | .691 | |

| It is worth extending the sites of protected nature in this area | .716 | |

| It is important that the municipality has been included in the European network | .693 | |

| People move here so as to live closer to protected nature | .653 | |

| It is also important to protect nature outside of the national parks | .611 | |

Component values lower than 5 have not been shown for clarity of interpretation. Extraction method—Principal Components. Rotation method—Varimax with Kaiser normalisation. Rotation converged in 3 iterations. For clarity only factor load values greater than 4 have been shown

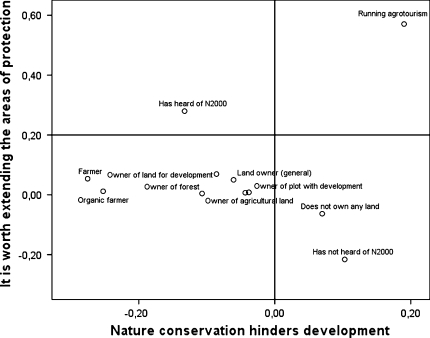

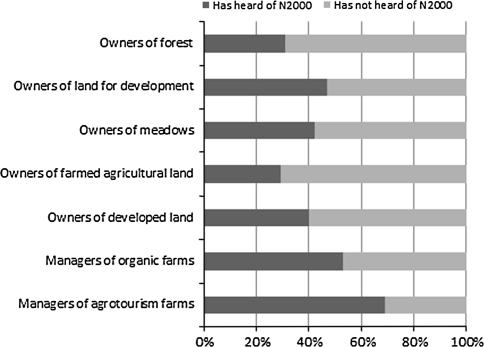

The two dimensions (represented by factor scales) distinguished are, firstly, the position that forms of nature conservation hinder the development of towns/villages found in the vicinity and, secondly, that it is worth extending the areas of protected nature. The resulting factor scales allow the selected groups to be represented on these figures. Figure 4 represents the comparison of the potential conflict groups identified above and the beneficiaries, as well as the groups of respondents divided according to land and the associations held about the Natura 2000 programme. The groups were compared according to their position along the two dimensions distinguished by factor analysis. The most interesting results from the comparison of the positions of various groups on the factor scales is that those who have heard of Natura 2000 are more favourably inclined toward extending the areas of protected nature than those who do not know anything about the programme. Also interesting is the ambivalent position of those running agrotourism businesses. They are high up both on: the scale representing a positive opinion toward extending the areas of nature conservation and the scale representing the perception of the nature conservation forms as a hindrance to the development of the town/village.

Fig. 4.

The positions of the selected groups of respondents on the dimensions distinguished in the factor analysis

National Versus European Forms of Nature Conservation in the Opinion of Local Communities

As in the case of local government members, the opinions of local communities concerning Natura 2000 are mostly based on their attitude to the conservation system currently in use in Poland. All of the municipalities studied that were included in the survey have national parks within their boundaries, or are found in their vicinity.

Almost all the respondents (93%) admit that it is good that local nature is conserved (aggregate “definitely yes” and “probably yes” responses) (Fig. 5). Those who live in the area of currently existing national parks or their surroundings do not consider them to be a nuisance (73%). Also, the park itself is not seen as a hindrance (79%) or an obstacle to the municipality’s development. What is more, the management of wildlife is generally left by the respondents to the competence of institutions dealing with nature conservation, and not that of land owners. This is because more than half the respondents (63%) think that land owners should not decide by themselves about wild animals on their land, leaving this matter to top-down decisions. A similar situation occurs in many various local conservation organisations. They are perceived rather favourably and are not considered harmful to the residents’ interests (78%). A large proportion of the respondents are in favour of conserving nature also beyond national parks and consider it important that Natura 2000 was introduced into their municipality (92 and 83%, respectively); fewer of them, however, are in favour of extending the protected areas in their vicinity. This, however, would not be reflected in their political preferences. More than half the residents (57%) would support a candidate for the post of local leader who generally plans to extend protected areas. Opinions vary among respondents of various places (Table 3). The introduction of Natura 2000 matters least for residents of Cisna and LipnicaWielka (χ2 = 12.181, P < 0.05), which are located closest to the currently existing national parks. At the same time the respondents from these municipalities are most critical of local nature conservation organisations (χ2 = 16.694, P < 0.005), and the hindrance to people caused by the need to conserve nature (χ2 = 23.570, P < 0.005). The residents of the Orawa region (the LipnicaWielka and Jabłonka villages), however, are more often of the opinion, that it is the owners who should decide about nature on their land (χ2 = 22.984, P < 0.005).

Fig. 5.

Assessment of the influence of nature and forms of conservation on people’s lives in a given place

Local and Regional Connotations of Introducing New Nature Conservation Programmes

The results of this study were affected by the characteristics of the municipalities and regions where it was conducted. Both the general assessment of the Natura 2000 programme, the opinion or the way it was expressed by local governments and residents of the alpine bioregion were clearly different from that of the continental bioregion. In 64% of alpine municipalities and 42% of continental municipalities, opinions about the proposed site boundaries were unequivocally negative (Table 2). Note that the percentage of positive opinions was similar in both regions presented whereas more negative opinions came from the local governments of the alpine region. Both regions also differ in the language they use to justify their opinions. Comments from the continental region are more often moderate, written in official language, whereas in those coming from the alpine region, the proposed designations of the Natura sites were expressed in a more emotional way. In both regions, however, similar arguments were used in support of negative opinions, or in requests for modification to the designated boundaries and in the examples where possible conflicts were identified, which may occur after the Natura sites are established in the planned locations.

The results of the survey also reveal considerable differences, especially in terms of activities currently undertaken by their residents and those planned for the nearest future. Residents’ plans differ between individual municipalities: statistically significant differences were noted in such areas as the intention to establish their own businesses (χ2 = 25.322, P < 0,005) run agrotourism (χ2 = 57.941, P < 0,005) or apply for subsidies for farming (χ2 = 28.545, P < 0,005) (Table 3). The most entrepreneurial plans involving their own businesses are noted for residents of the Cisna municipality (located in a popular tourist area) and of the Jabłonka municipality (with the highest population among municipalities surveyed). More than half of the Cisna residents hope to live on agrotourism and about 20% of those in Orawa region municipalities (Jabłonka and LipnicaWielka). The opposite proportion is noted for plans for farming subsidies, which are declared by every second resident of Jabłonka and LipnicaWielka, every third resident of Cisna and every fourth resident of Komańcza.

Consequently, the areas under study vary in terms of individual stakeholders. They could potentially be involved in conflicts or be beneficiaries of the programme and for this reason were singled out for consultation or educational actions. The potential conflict groups singled out in the following studies are: owners of plots with developments, owners of land designated for development in the area development plans and woodland owners (Table 5). Homeowners and estate managers on the sites included in the protected areas are anxious about possible restrictions (e.g., on carrying out renovations or other projects or changes in the use of the land), owners of plots for development perceive difficulties in, restrictions on, or refusal of, planning permission. Woodland owners in turn see restrictions such as prohibited logging. Irrespective of whether these fears are founded or not, they constitute barriers to community acceptance of the boundaries of the protected areas. Potential beneficiaries of the Natura 2000 programme are owners of meadows or agricultural land and those running agrotourism businesses or engaged in organic farming. The latter two groups to the highest degree share the opinion that actions for nature conservation hinder economic development. On the other hand, there are among those surveyed such people who are most favourably inclined toward the extension of protected areas. This is related to their superior knowledge of the program, compared to other groups, though it is still incomplete. Farmers seem however less interested in the extension of protected areas not noticing the direct effect of nature conservation on the decrease in business investment activity. They are also the group that is least informed about the Natura 2000 programme (Figs. 4, 6).

Table 5.

Shares of potential conflict groups and beneficiaries among residents of the studied municipalities

| Cisna | Komańcza | Jabłonka | Lipnica Wielka | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Running an agrotourism business | 19% | 4% | 4% | 1% |

| n = | 28 | 6 | 7 | 1 |

| Running an organic farm | 1% | 6% | 2.50% | 2% |

| n = | 2 | 9 | 4 | 3 |

| Owners of developed land | 78% | 70% | 81% | 74% |

| n = | 63 | 53 | 77 | 64 |

| Owners of cultivated agricultural land | 13% | 51% | 68% | 69% |

| n = | 11 | 38 | 65 | 59 |

| Owners of meadows | 48% | 67% | 72% | 72% |

| n = | 39 | 50 | 68 | 62 |

| Owners of land for development | 35% | 15% | 41% | 42% |

| n = | 28 | 11 | 39 | 36 |

| Owners of forest | 25% | 25% | 76% | 85% |

| n = | 20 | 19 | 72 | 73 |

The important groups of potential beneficiaries are shown in the italicized font, and the potential conflict groups in the bold font. The percentages in the table do not come to 100 as these are answers to multiple choice questions

Fig. 6.

Knowledge of the Natura 2000 programme amongst key groups of respondents

The individual categories of both the conflict groups and beneficiaries identified in the study are often interlinked. Often, one person runs more than one type of business because they own several types of land. The Orawa region and the Komańcza municipality in the Bieszczady mountains contain the highest numbers of beneficiaries who can make use of the programmes for farmers and for maintaining meadows (Table 5). The Komańcza municipality also has the highest percentage of people engaged in organic farming. In the Cisna municipality, however, the vast majority of people make their living from running agrotourism businesses. As regards conflict groups, the vast majority in all municipalities were noted amongst those who own plots with developments—they make up over two thirds of the residents in all the studied locations. The greatest share of people who own plots for development is found in the Orawa municipalities. Although this share is significantly lower than in the case of those owning already developed plots, the risk of conflict is potentially greater as a result of potential obstacles in carrying out any building plans. In the Orawa municipalities, the percentage of people who own woodland is also significant—at least three times that of the municipalities studied in the Bieszczady mountains.

Discussion

The Value of New Protected Areas for Local Communities

New solutions to the nature conservation sector, especially those imposed as top-down decisions, are often reluctantly received by local communities (Lee and Roth 2006). This is most often the case for people living around national parks, but also around other protected areas, included those covered by the Natura 2000 network (Burger 2005, 2007, 2008; Lewis 1996; Stoll-Kleeman 2001). Similar to our present study, the residents of protected areas appreciate the neighbouring natural environment and agree with the necessity of the actions of the institutions managing natural resources. They often appreciate the methods of such actions. But their understanding of the nature conservation principles is seldom complete. Consequently, in spite of their friendly attitude, various conflicts emerges, as in the case of the municipalities we studied. Such misunderstandings most often pertain to the physical development of areas adjacent to those protected, as well as decision-making issues concerning nature conservation on private land (Daniels and Walker 1997; Depoe and others 2004; Simmons 2001). All of the arguments mentioned above could be heard from members of local management that were respondents to this study.

Acceptance/Non-Acceptance of Natura 2000 Governance Policy

In the case of the Natura 2000 programme, the local governments and residents of municipalities located in the protected areas are of the opinion that the lack of the programme’s acceptance primarily stems from the unavailability of information and hence a lack of knowledge and false opinions regarding the beliefs of other groups. Members of local governments also point out bad communication at various decision-making levels: from the national to the local (International Union for Conservation of Nature 2005; Stern 2004). In the case of Poland the communication system between the representatives of the Polish Ministry of the Environment responsible for the Natura 2000 implementation and local governments was most severely criticized. In contrast, the local government’s position was seen as consistent with that of their community.

The opinions of members of Polish local governments and communities do not fundamentally differ from those observed in other EU countries, where the introduction of practically all phases of Natura 2000 has been and still is accompanied by general reluctance and consequent conflicts (Apostolopoulou and Pantis 2009; Hiedenpää 2002). That is why current trends in managing the protection of biodiversity in the EU are increasingly often perceived as needing to be complemented with bottom-up initiatives. The latter seem essential primarily to legitimize conservation programmes that are implemented and result in these programmes’ efficient functioning (Kluvánková-Oravská and others 2009; Winter 2003).

Providing Information About the Programme

It seems thus justified that Poland should participate more widely in European communication programmes firstly due to economic reasons and secondly to the satisfaction of communities. The share of European funding in Natura 2000 implementation in Poland has been very high so far and accounted for as much as 65% of the total expenditure whereas the rest has been completed by the state budget and funds from other institutions (Jaśkiewicz 2008). One of the most promising EU programme Poland has just entered is the EU LIFE-Nature Programme (currently called LIFE+) (Silva and others 2009). Its effectiveness—expressing in an increase in business and activity on the Natura 2000 covered areas—significantly depends on the proper timing of implementation, the scale of the actions, their relevance, as well as the involvement of local communities in the planned actions (Audretsch and Keilbach 2006; Sundseth 2004). Completing such programmes at a national level, which, although very few and much delayed, are well received by society. A good example is the initiative of local authorities of the Malopolska Province, who themselves with assistance of the EU funds, organised a series of information (consultation) meetings for residents, investors and decision-makers of municipalities located in Natura 2000 areas (oral information from employees of the Regional Directorate of Environmental Protection; Cent and others 2010). People planning communication programmes should take into account local social factors. It is especially important in countries in transition, such as Poland, which are primarily oriented at avoiding or resolving existing conflicts connected to the introduction of new forms of nature conservation (Beltran 2000; Peters 1999; Pujadas and Castillo 2007), and not in order to manage the protected sites in a better way as is the case in the richest countries (Borrini-Feyerabend and others 2004; Ludwig and others 2001).

Nature Conservation Governance: Multi-Level Structure

One of the consequences of poor communication between decision-makers is the residents’ lack of participation in the decision-making processes, especially those concerning physical development. This problem seems more complex in Poland, as it depends on many factors. In Poland, the socialist system strongly affected the functioning of public administration and the development of civil society (Gliński 1994, 1996). As compared to Western countries, the nature conservation sector still has less support from the population. Also, such a tradition persists of small participation in social initiatives (Bell and others 2008; Cent and others 2007). Finally there are no clear legal regulations for participatory approaches. For instance, with regard to national parks, this issue has practically been neglected in the national acts of parliament regarding nature protection (Dz.U.2008.201.1237, Dz.U.2004.92.880). On the one hand, the dissatisfaction of local communities associated with not being treated as a party in local decision-making is understandable. On the other hand, even in areas where local communities are encouraged to such participation, (e.g., by national park managements) they often have groundless and false convictions about the harmful consequences of the conservation measures planned. Consequently, the local communities do not support their undertaking and implementation (Terlecka and Górecki 1998).

The effect of the lack of participation in the management of protected areas is additionally aggravated by the fact that people are generally positive about nature conservation activities as long as it does not interfere with their personal or institutional goals and needs (Young and others 2005; Chuenpagde and others 2004). Convincing society and political activists of the need for the programme will depend on, amongst other things, whether nature conservation is perceived as necessary and factually justified (US Environmental Protection Agency 2001). People surveyed in this study were willing to invest in areas that are relatively harmless to the local natural environment, but at the same time they complained about Natura 2000 hindering business activity. Depending on local conditions, the residents’ determination concerning individual or the municipality’s development can be so high that it veils the possible consequences to the natural environment. But if the locals are familiarised in advance with the negative impact on nature of the project, or other business activity, their resistance to the implementation of a harmful undertaking will dwindle (Mendez-Contreras and others 2008).

Interdisciplinary Approach: A Way to an Effective Sustainable Development Policy

Opinions regarding and support for the Natura 2000 programme often vary among places or regions. It seems understandable that there are differences in business activity undertaken now and those planned for the nearest future among residents of individual places and regions, and opinions concerning the expansion of protected areas. Similar dependence can be noted when viewing the opinions of local governments on the territory of almost the whole of Poland. Poland as a new EU member country has become a beneficiary of relatively high union funds intended for investment, including those most controversial in terms of environmental protection (Kiejzik-Głowińska and Samsel 2006). Their implementation was blocked by the work going at the same time to determine Natura 2000 sites. This, in turn, led to local governments and communities growing frustrated, especially in underinvested areas, waiting for years for specific projects on their area to be completed. The practical implementation of principles, including those of sustainable development, which go beyond the traditional forms of conservation, still seems ineffective, in both the conservation and investment sectors (Najwyższa Izba Kontroli 2008).

The anxiety regarding financial matters, often mentioned by local governments, are not associated with the possible hindering of economic development in their place or region due to the introduction of Natura 2000, but also the very “service” of the programme. Local governments from all municipalities studied, in their opinions clearly draw attention to the costs of managing the protected areas as well as the higher costs of other indirectly linked procedures, which they will have to meet. Generally, decision-making in nature conservation in Europe, particularly in connection with the designation of the Natura 2000 network, does not sufficiently make use of cost effective analysis (Maiorano and others 2007). This mistake was also made at least partly in the process of designating the sites in Poland (Makomaska-Juchiewicz and Tworek 2003). A direct consequence of this situation is the underinvestment in individual tasks of the programme, including their staffing. In Poland the number of professional staff trained for Natura 2000 is still insufficient. Instead, the Ministry of the Environment delegated the responsibilities associated with the programme to the current personnel of organisations responsible for its development (i.e., Polish State Forests, National Parks, regional Water Management Authorities, etc.). The resulting shortage of staff and consequently general disinformation only increase the local governments’ reluctance to the programme (Walder and Schnell 2006).

To introduce the Natura 2000 programme in Poland and in consequence the sustainable development strategy, the authorities have to change the management of natural assets system, mainly by encompassing the wider—interdisciplinary—context comprising the social aspects of nature conservation (i.e., public participation), and creating a system allowing those aspects to be taken into consideration in practice (Bath 2005; Harwood 2000; Schwarz 2005). The experience of other countries shows that only such an attitude allows tasks of a sustainability strategy, Natura 2000 included, to be effectively accomplished. It increases the chance of a sustainability strategy to be effectively accomplished, resulting in a proper operation of the sites in the future, especially those that are designated on private land where there is a need to ensure realistic opportunities for nature conservation often dependant on the owners’ willingness to get involved in conservation and on the sympathies of the local authorities (Charbonneau 1997; Giordano 2004; The Gallup Organization 2007; Walder and Schnell 2006). It will be difficult to achieve the aims of Natura 2000 without elements being taken up by local nature conservation plans and policy. Even where a given area is densely covered by the network, its successful conservation depends on the behaviour and management of areas outside of it, which is a challenge not only for managing those areas themselves, but also for broader thinking about the needs of nature and sustainable development (Dimitrakopoulos and others 2004).

Recommendations

Effective implementation of the new forms of nature conservation will be possible if a proper policy is developed and adopted in this respect. Decision-makers should especially:

revise and modify the current approach to governance, management and physical planning. This primarily stems from the need to reconcile sustainable development tasks (economic development with those of nature conservation) and increase the effectiveness of natural resources management at all ecological and administrative levels (Grodzińska-Jurczak 2008),

encourage local communities to actively participate in the new forms of nature conservation, while at the same time ensuring the introduction of appropriate legal solutions to safeguard their interests,

take other members of society into consideration. They may indirectly reap benefits or incur losses as a result of, for example, changes in the amount of recreational use of the areas (Borrini-Feyerabend and others 2004; Worth 2002). A well introduced programme has the chance to initiate a change in the approach to nature conservation so that it is more participatory,

make use of the experience of Western European countries, as many of the problems Poland is currently struggling with have already been encountered there and successfully resolved. That is, adopt an interdisciplinary approach, namely a combination of the efforts of specialists in the natural and social sciences,

use the resources of the EU programmes in a more effective way, especially by wider and more active participation in communication programmes such as LIFE+ while continuing regional and local initiatives already underway. Communication should be conducted by interdisciplinary qualified staff providing reliable information about the principles of action of new forms of nature conservation and the aid programmes accompanying it. Intense communication should be in particular addressed at the most conflicting-prone groups, including, local governments’ representatives and legal owners of the plots included in the network.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the MSc students at the Jagiellonian University (Krakow) for taking part as interviewers in this project. Thanks also to the representatives of Jabłonka, LipnicaWielka, Komańcza, Cisna governments for their fruitful co-operation and ongoing support. Finally, thanks go to Stanisław Tworek and Małgorzata Makomaska-Juchiewicz (Institute of Nature Protection, Polish Academy of Science, Kraków, Poland) for sharing their experiences, and for their strategic advice during the project’s delivery and evaluation. The study described here was done as part of two research projects “Effectiveness of protection of Natura 2000 sites and social aspects of the programme’s implementation in Poland” funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (grant no. N305 094 32/3185) and “Information, education and communication for the natural environment” sponsored by the Jagiellonian University (grant no. WRBW/DS/INoŚ/760).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Alphandery P, Fortier A. Can a territorial Policy be based on science alone? The system for creating the Natura 2000 Network in France. Sociologia Ruralis. 2001;41(3):311–328. doi: 10.1111/1467-9523.00185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrzejewski R, Weigle A. Różnorodność biologiczna Polski. Warszawa, Poland: Narodowa Fundacja Ochrony Środowiska; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniewicz P (2006) Partnerstwo czlowieka i przyrody. Dolnoslaska Fundacja Ekorozwoju.http://www.iee.org.pl/rozwoj/docs/PARTNERSTWO_CZLOWIEKA_I_PRZ.pdf [2 September 2008]

- Apostolopoulou E, Pantis JD. Conceptual gaps in the national strategy for the implementation of the European Natura 2000 conservation policy in Greece. Biological Conservation. 2009;142(1):221–237. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2008.10.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch DB, Keilbach M (2006) Entrepreneurship, growth and restructuring. discussion papers on entrepreneurship. Growth and Public Policy 2006-13, Max Planck Institute of Economics, Group for Entrepreneurship, Growth and Public Policy

- Bath A (2005) Seminar on transboundary management of large carnivore populations. Osilnica, Slovenia, 15–17 April 2005. Strasbourg: Council of Europe T-PVS (2005)

- Beaufoy G. The EU Habitats Directive in Spain: can it contribute effectively to the conservation of extensive agro-ecosystems? Journal of Applied Ecology. 1998;35:974–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.1998.tb00017.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S, Marzano M, Cent J, Kobierska H, Podjed D, Vandzinskaite D, Reinert H, Armaitiene A, Grodzinska-Jurczak M, Mursic R. What counts? Volunteers and their organisations in the recording and monitoring of biodiversity. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2008;17(14):3443–3454. doi: 10.1007/s10531-008-9357-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran J (ed) (2000) Indigenous and traditional people and protected areas: principles, guidelines and case studies. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK; WWF International, Gland, Switzerland

- Beunen R. European nature conservation legislation and spatial planning: for better Or for worse? Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 2006;49(4):605–619. doi: 10.1080/09640560600747547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bland F, Thiry E (2003) Wdrażanie Europejskiej Sieci Ekologicznej Natura 2000 we Francji. In: Makomaska-Juchiewicz M, Tworek S (eds) Ekologiczna sieć Natura 2000 – problem czy szansa?, Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN, Kraków

- Borrini-Fayerabend G, Kothari A, Oviedo G. Indigenous and local communities and protected areas. Toward equity and enhanced conservation. Gland, Switzerland, Cambridge, UK: IUCN; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Burger T. Świadomość ekologiczna społeczeństwa polskiego. Warszawa, Poland: Instytut Gospodarki Przestrzennej i Mieszkalnictwa; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Burger T. Konflikt ekologiczny–specyfika i studium przypadków. In: Starczewski, editor. Proceedings of the Conference Konflikt Ekologiczny. Warszawa, Poland: Centrum Informacji o Środowisku; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Burger T. Polacy w zwierciadle ekologicznym. Warszawa, Poland: Institute for Sustainable Development; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cash D, Adger WW, Berkes F, Garden P, Lebel L, Olsson P, Pritchard L, Young O. Scale and cross-scale dynamics: governance and information in a multilevel world. Ecology and Society. 2006;11(2):8. [Google Scholar]

- Cent J, Kobierska H, Grodzińska-Jurczak M, Bell S. Who is responsible for Natura 2000 in Poland?—a potential role of NGOs in establishing the programme. International Journal of Environment and Sustainable Development. 2007;6:422–435. doi: 10.1504/IJESD.2007.016245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cent J, Grodzińska-Jurczak M, Nowak N. Ocena efektów małopolskiego programu konsultacji społecznych wokół obszarów Natura 2000. Public consultation programme Natura 2000 sites in Małopolska—effects’ evaluation. Chrońmy Przyrodę Ojczystą. 2010;66(4):251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Office Poland (GUS). Access online May 05, 2009 http://www.stat.gov.pl

- Charbonneau S. Natura 2000: uneopportunite de dialogues a saisir. Natures Sciences Societies. 1997;5:63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chuenpagdee R, Fraga J, Eua’N-Avila Progressing toward comanagement through participatory research. Society and Natural Resources. 2004;17:147–161. doi: 10.1080/08941920490261267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Communities (CEC) (2005) Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament. Draft declaration on guiding principles for sustainable development, COM (2005) 218 final. Brussels

- Daniels SE, Walker GB (1997) Foundations of natural resource conflict. In: Solberg B, Miina S (eds) Proceedings of the international conference on conflict management and public participation in land management, Joensuu, Finland, 17–19 June 1996. EFI Proceedings, vol 14, pp 13–36

- de Piérola SCF, Carbonell X, Garcia JGL, Hernández FH, Zamanillo MS (2009) Natura 2000 i społeczeństwo. Instrumenty komunikacji społecznej w zarządzaniu siecią Natura 2000, EDIT, Warszawa

- Depoe SP, Delicath JW, Elsenbeer MFA. Communication and public participation in environmental decision making. NY: State University of New York; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrakopoulos PG, Memtsas D, Troumbis AY. Questioning the effectiveness of the Natura 2000 Species Areas of Conservation strategy: the case of Crete. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2004;13:199–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-822X.2004.00086.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dz.U.2003.78.706 Konwencja o dostępie do informacji, udziale społeczeństwa w podejmowaniu decyzji oraz dostępie do sprawiedliwości w sprawach dotyczących środowiska, sporządzona w Aarhus dnia 25 czerwca 1998 r. Convention on Access to information, public participation in decision-making and Access to justice in environment al matters done at Aarhus, Denmark

- Dz.U.2004.92.880 Ustawa z dnia 16 kwietnia 2004 r. o ochronie przyrody. Act on nature protection. Poland

- Dz.U.2008.201.1237 Ustawa z dnia 3 października 2008 r. o zmianie ustawy o ochronie przyrody oraz niektórych innych ustaw. Act on a change of act of nature protection and some other acts. Poland

- European Commission (2004) Report from the Commission on the Implementation of the Directive 92/43/EEC on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and Wild Fauna and Flora. No. 845. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg

- Fischer A, Paige A, Bliss JC. Framing conservation on private land: conserving oak in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Society and Natural Resources. 2009;22:884–900. doi: 10.1080/08941920802314926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folke C, Pritchard L, Berkes F, Colding J, Svedin U (2007) The problem of fit between ecosystems and institutions: ten years later. Ecology and Society 12(1):30. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss1/art30/

- Giordano K. Planowanie zrównoważonego rozwoju gminy w praktyce. Lublin, Poland: Wydawnictwo KUL; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gliński P. Environmentalism among Polish youth: a maturing social movement? Communist & Post-Communist Studies. 1994;27:145–159. doi: 10.1016/0967-067X(94)90022-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gliński P. Polscy Zieloni: ruch społeczny w okresie przemian. Warszawa, Poland: IFiS PAN; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Grodzińska-Jurczak M. Rethinking of nature conservation policy in Poland—the need of human dimension approach. Human Dimensions of Wildlife. 2008;13:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood J. Risk assessment and decision analysis in conservation. Biological Conservation. 2000;95:219–226. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3207(00)00036-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiedenpää J. European-wide conservation versus local well-being: the reception of the Natura 2000 Reserve Network in Kavia, SW-Finland. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2002;61:113–123. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2046(02)00106-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Implementation of Natura2000 in New EU Member States of Central Europe. Assessment Report. Warszawa, Poland: IUCN; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jaśkiewicz J. Dilemmas for sustainable development in Poland. Problems of Sustainable Development. 2008;3(1):33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Julien B. Voicing interests and concerns—NATURA 2000: an ecological network in conflict with people. Forest Policy and Economics. 2000;1(3):357–366. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9341(00)00031-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiejzik-Głowińska M, Samsel M. Droga a Natura 2000 - trudne doświadczenia okresu przejściowego. Problemy ocen środowiskowych. 2006;4(35):82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kluvánková-Oravská T, Chobotová V, IlonaBanaszek (2009) From Government to governance for biodiversity: the perspective of central and eastern European transition countries. Environmental Planning and Governance 19:186–196

- Koester V. The Compliance Committee of the Aarhus Convention—an overview of procedures and jurisprudence. Environmental Policy and Law. 2007;37(2–3):83. [Google Scholar]

- Królikowska K. Konflikty społeczne w polskich parkach narodowych. Kraków, Poland: Oficyna Wydawnicza Impuls; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Larobina MD. A report on Poland and European union accession. Multinational Business Review. 2001;9(2):8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Roth WM. Community-level controversy over a natural resource: toward a more democratic science in society. Society and Natural Resources. 2006;19:429–445. doi: 10.1080/08941920600561124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C (1996) Managing conflicts in protected areas. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, Cambidge, UK, 100 pp

- Ludwig D, Mangel M, Haddad B. Ecology, conservation, and public policy. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematica. 2001;32:481–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maiorano L, Falcucci A, Garton EO, Boitani L. Contribution of the Natura 2000 network to biodiversity conservation in Italy. Conservation Biology. 2007;21(6):1433–1444. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makomaska-Juchiewicz M (2007) Sieć obszarów Natura 2000 w Polsce In Gregorczyk M (ed) Integralna Ochrona Przyrody. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN, Kraków, pp 165–176

- Makomaska-Juchiewicz M, Tworek S. Ekologiczna Sieć Natura 2000. Problem czy szansa? Kraków, Poland: Instytut Ochrony Przyrody; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Małopolski Urząd Wojewódzki (2008) Bez emocji o Naturze 2000 – informacja prasowa, http://www.muw.pl/PressArticlePage.aspx?id=5033 dostęp 20.04.2010

- McCauley D. Sustainable development and the governance challenge: the French experience with Natura 2000. European Environment. 2008;18(3):152–167. doi: 10.1002/eet.478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Contreras J, Dickinson F, Castillo-Burguete T. Community member viewpoints on the RiaCelestun Biosphere Reserve, Yucatan, Mexico: suggestions for improving the community/natural protected area relationship. Human Ecology. 2008;36(1):111–123. doi: 10.1007/s10745-007-9135-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Environment Poland. http://www.natura2000.mos.gov.pl. Accessed 05 May 2009

- Najwyższa Izba Kontroli (NIK) Informacja o wynikach kontroli wdrażania ochrony na obszarach Natura 2000. Warszawa: NIK; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oana B. Natura 2000 network an opportunity for rural space sustainable development. Buletin USAMV-CV. 2006;62:179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2009) http://www.hdr.undp.org/en/statistics. Accessed 05 May 2009

- Ostermann O. The need for management of nature conservation sites designated under Natura 2000. Journal of Applied Ecology. 1998;35:968–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.1998.tb00016.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paavola J, Gouldson A, Kluvánková-Oravská T. Interplay of actors, scales, frameworks and regimes in the governance of biodiversity. Environmental Policy and Governance. 2009;19(3):148–158. doi: 10.1002/eet.505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palerm J. The habitats directive as an instrument to achieve sustainability? An analysis through the case of the Rotterdam Mainport Development Project. European Environment. 2006;16:127–138. doi: 10.1002/eet.413. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Partyka J, Żółciak J. The conflict between man and nature as exemplified by the Ojców National Park. In: Hibszer A, Partyka J, editors. Between nature protection and economy—closer to protection. Man–nature conflicts in the areas protected by law in Poland. Sosnowiec – Ojców, Poland: Polskie Towarzystwo Geograficzne Oddział Katowicki; 2005. pp. 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Perzanowska J, Grzegorczyk M (2009) Obszary Natura 2000 w Małopolsce. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN, Kraków, Poland, 311 pp

- Peters J. Understanding conflicts between people and parks at Ranomafana, Madagascar. Agriculture and Human Values. 1999;16:65–74. doi: 10.1023/A:1007572011454. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pujadas A, Castillo A. Social participation in conservation efforts: a case study of a biosphere reserve on private lands in Mexico. Society and Natural Resources. 2007;20(1):37–55. doi: 10.1080/08941920600981355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz M. How conservation scientists can help develop social capital for biodiversity. Conservation Biology. 2005;20(5):1550–1552. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JP, Toland J, Jones W, Eldridge J, Hudson T, Thorpe E, O’Hara E (2009) Protecting Europe’s nature: learning from LIFE. Nature conservation best practices. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg, 68 pp

- Simmons C. The local articulation of policy conflict: land use, environment, and Amerindian rights in Eastern. Amazonia. 2001;54(2):241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Soma K. Farming participation with multicriterion evaluations to support the management of complex environmental issues. Environmental Policy and Governance. 2009;20:89–106. doi: 10.1002/eet.534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stec S, Casey-Lefkovitz S, Jendrośka J, editors. The Aarhus convention—an implementation guide. New York and Geneva: United Nations; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stern MJ. Understanding local reactions to protected areas. In: Hamú D, Auchincloss E, Goldstein W, editors. Communicating protected areas, commission on education and communication. Gland, Switzerland, Cambridge, UK: IUCN; 2004. pp. 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll-Kleeman S. Barriers to nature conservation in Germany: a model explaining opposition to protected areas. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2001;21(4):369–385. doi: 10.1006/jevp.2001.0228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundseth K (2004) LIFE—Nature: communicating with stakeholders and the general public. Best practices examples for Natura 2000, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxemburg—Belgium, 41 pp

- Symonides E (2008) Ochrona przyrody. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego Warszawa, Poland, 766 pp

- Terlecka K, Górecki A. Ojców National Park—forming attitudes and ecological awareness of its inhabitants. Prądnik, Prace Muzeum Szafera. 1998;11(12):369–396. [Google Scholar]

- The Gallup Organization (2007) Attitudes of Europeans toward the issue of biodiversity—Analytical Report. Flash Eurobarometer Series 219, 71 pp

- Unnerstall H. ‘Sustainable development’ as a criterion for the interpretation of Article 6 of the habitats directive. European Environment. 2006;16:73–88. doi: 10.1002/eet.408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) (2001) Stakeholder involvement & public participation at the U.S. EPA. Lessons, learned, barriers, & innovative approaches, prepared for the office of policy, economics, and innovation, Washington DC

- Visser MJ, Moran E, Regan M, Gormally M, Skeffington S. The Irish agri-environment: how turlough users and non-users view converging EU agendas of Natura 2000 and CAP. Land Use Policy. 2007;24:362–373. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2006.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walder C, Schnell AA (2006) Natura2000 in Europe. An NGO assessment, WWF, Budapest, Hungary, 92 pp

- Wallace GN, Theobald DM, Ernst T, King K. Assessing the ecological and social benefits of private land conservation in Colorado. Conservation Biology. 2008;22(2):284–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber N, Christophersen T. The influence of non-governmental organizations on the creation of Natura 2000 during the European Policy process. Forest and Policy Economics. 2002;4:1–12. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9341(01)00070-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winter G (2003) Environmental principles in community law. In: Jans JH (ed) The European Convention and the Future of European Environmental Law. Amsterdam Europa Law Publ. pp 3–25

- Worth S (2002) The challenge of community-based protection areas—rhetoric or reality? Parks, Local Communities and Protected Areas 12

- Young J, Watt A, Nowicki P, Alard D, Clitherow J, Henle K, Johnson R, Laczko E, McCracken D, Matouch S, Niemela J, Richards C. Toward sustainable land use: identifying and managing the conflicts between human activities and biodiversity conservation in Europe. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2005;14(7):1641–1661. doi: 10.1007/s10531-004-0536-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]