Abstract

In Europe, colorectal cancer is the most common newly diagnosed cancer and the second most common cause of cancer deaths, accounting for approximately 436,000 incident cases and 212,000 deaths in 2008. The potential of high-quality screening to improve control of the disease has been recognized by the Council of the European Union who issued a recommendation on cancer screening in 2003. Multidisciplinary, evidence-based European Guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis have recently been developed by experts in a pan-European project coordinated by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. The full guideline document consists of ten chapters and an extensive evidence base. The content of the chapter dealing with pathology in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis is presented here in order to promote international discussion and collaboration leading to improvements in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis by making the principles and standards recommended in the new EU Guidelines known to a wider scientific community.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer screening, Multidisciplinary evidence-based guidelines, Quality assurance, Histopathology, Classification, Precursor lesions

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is a significant health problem, the importance of which will increase substantially in the coming years [1]. In Europe, colorectal cancer is the most common newly diagnosed cancer and the second most common cause of cancer deaths, accounting for approximately 436,000 incident cases and 212,000 deaths in 2008 [2]. Randomized trials have shown that systematic screening of a target population of suitable age can reduce colorectal cancer (CRC) by detecting asymptomatic lesions [3–5]. Early treatment is more effective and has a lower morbidity and mortality. Moreover, the endoscopic removal of adenomas reduces the incidence of CRC by stopping the progression of precursor lesions to cancer. The potential of high-quality screening to improve control of CRC has been recognized by the Council of the European Union who issued a recommendation on cancer screening in 2003 [6]. The recommendation encourages the EU Member States to implement population-based screening programmes using evidence-based tests for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer, according to European Quality Assurance Guidelines where they exist. Comprehensive European Guidelines for quality assurance of breast and cervical cancer screening have been prepared by experts and published by the European Commission [7, 8]. Multidisciplinary, evidence-based European Guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis have recently been developed by experts in a pan-European project coordinated by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. The comprehensive guidelines cover the entire screening process including clinical aspects, public health, organization and communication. The full guideline document consists of ten chapters and an extensive evidence base [9]. The content of the chapter dealing with pathology in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis [10] is presented here in a slightly modified format in order to promote international collaboration in improvement of colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis by making the principles and standards recommended in the new EU Guidelines known to a wider scientific community. This area is rapidly developing and future evidence-based revisions will be required.

The pathology service plays a very important role in colorectal cancer screening since the management of participants in the programme depends on the quality and accuracy of the diagnosis. Pathology affects the decision to undergo further local and/or a major resection as well as surveillance after screening. The adoption of formal screening programmes leads to improvement not only in the management of early but also advanced disease by the introduction of guidelines, quality standards, external quality assurance and audit. In screening programmes, the performance of individuals and programmes must be assessed and it is advantageous if common diagnostic standards are developed to ensure quality, recognise areas where sufficient evidence is still lacking, and initiate high-quality studies to answer these questions. The present chapter suggests practical guidelines for pathology within a colorectal screening programme. We have concentrated on the areas of clinical importance in the hope of standardising these across the European Union. In the associated annex [11], we deal with some of the more difficult areas and suggest topics for future research. We have included guidelines for the reporting and management of resected specimens in an attempt to move towards agreed minimum European standards of pathology in these areas as well. This is the first edition of what will be a continuing process of revision as new data emerge on the pathology, screening and management of colorectal cancer. We hope to set minimum standards that will be followed in all programmes and to encourage the development of higher standards amongst the pathology community and screening programmes.

Many lesions are found within a screening programme some of which are of little or no relevance to the aim of lowering the burden of colorectal cancer in the population. The range of pathology differs between the different approaches, with faecal occult blood programmes yielding later, more advanced disease than flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy screening. Programme activities must focus on the identification and appropriate management of invasive colorectal cancer and its precursors. The management of pre-invasive lesions involves surveillance to allow the prevention of future disease, whereas management of adenocarcinoma focuses on immediate treatment and decisions on local removal, or radical surgery with the potential for operative mortality. Overuse of radical surgery must be avoided and recommendations for its use must be balanced with the risks to the patient.

There are a number of lesions, especially in the serrated pathway leading from hyperplastic polyps to other serrated lesions and in some cases to adenocarcinoma, that may be difficult to diagnose and for which knowledge of their natural history and clinical implications is limited [12]. Further work is required in this area, but until we understand these lesions better it is recommended that all serrated lesions, with the exception of hyperplastic polyps, be fully removed.

Few data were present in the literature on this issue. This paucity of data is caused in part by a lack of standardisation in terminology and limited observer agreement. Furthermore, a lack of prospective studies precludes a clear indication of the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy for lesions in the serrated pathway. For more information, see Ref. [11]. The screening programme will also identify other non-serrated neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions and provide important data on such conditions.

Methods

The process of evidence-based guideline development is reported elsewhere in detail [13]. Briefly, scientific and editorial management was performed by an editorial board with experience in development of best practice guidelines, in programme management and in evaluation of strategies for CRC screening. The editorial board drafted an initial comprehensive outline of the Guidelines and recruited a multidisciplinary group of 50 experts across the European Union to collaborate in revising the outline and drafting the chapters according to an agreed methodology. An expert Literature Group consisting of epidemiologists with special expertise in the field of CRC and in critical appraisal of clinical studies provided technical and scientific support to the authors and editors in searching the relevant literature, assessing the methodological quality of retrieved studies and defining a grading system of the level of evidence and strength of the recommendations.

The subgroup of authors responsible for the presently reported chapter defined key clinical questions (modified Patient-Intervention-Comparison-Outcome-Study method) [14–16] for sensitive and specific bibliographic searches (Medline, Embase, Cochrane library) for the calendar years 2000–2008; articles suggested by authors were also considered. A study design hierarchy and inclusion/exclusion criteria were developed for each type of question (effectiveness, diagnostic accuracy, acceptability, etc.). The methodological quality of the studies retrieved for the clinical questions was assessed using validated checklists for systematic reviews [17], randomized controlled trials [18], observational studies [19] and diagnostic accuracy studies [20]. Evidence tables and summary documents with a synthesis of results and the level of evidence were produced for each question by the literature group.

The subgroup of authors responsible for the presently reported chapter received all the evidence tables and summary documents relating to the formulated clinical questions dealing with quality assurance in pathology of CRC screening and diagnosis. The authors elaborated the chapter draft describing the relevant issues and including issues deemed to be relevant for a comprehensive multidisciplinary guideline, but not covered by the key clinical questions. The authors summarized the available evidence, and included recommendations and conclusions, as well as a proposal for the strength of the evidence and the level of each of the recommendations based on the evidence collected by the literature group, their clinical experience, and any additional relevant references collected by the authors, including publications after December 2008. The manuscript draft was repeatedly reviewed and revised in workshops attended by the authors of all of the guideline chapters as well as the editors and the literature group to develop consensus on the final recommendations and other content. A preliminary and a nearly final draft of the present chapter was also reviewed and discussed in multidisciplinary, pan-European meetings on colorectal cancer screening conducted in 2008 and 2009 in which experts from the 27 EU member states participated.

For each recommendation the strength of evidence was indicated according to the following grading:

-

I.

Multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of reasonable sample size, or systematic reviews (SRs) of RCTs

-

II.

One RCT of reasonable sample size, or three or less RCTs with small sample size

-

III.

Prospective or retrospective cohort studies or SRs of cohort studies; diagnostic cross-sectional accuracy studies

-

IV.

Retrospective case–control studies or SRs of case–controls studies, time series analysis

-

V.

Case series; before/after studies without control group, cross-sectional surveys

-

VI.

Expert opinion

If applicable, the lack of sufficient evidence to make a recommendation was explicitly mentioned in the guideline text. The consensus of the authors and editors on the strength of a given recommendation was indicated according to the following grading:

-

A.

Intervention strongly recommended for all patients

-

B.

Intervention recommended

-

C.

Intervention to be considered but with uncertainty about its impact

-

D.

Intervention not recommended

-

E.

Intervention strongly not recommended

Statements of advisory character that the authors considered to be good practice but not of sufficient importance to warrant formal grading were included in the chapter text.

In the final editing, the consistency and coherence of recommendations was checked by the editorial board. Strong recommendations, e.g. with grading A or E, but with comparatively low levels of evidence, e.g. levels III–VI, were accepted if an appropriate explanation was provided by the authors.

Classification of lesions in the adenoma–carcinoma sequence

A colorectal adenoma is defined as a lesion in the colon or rectum containing unequivocal epithelial neoplasia. Classification of adenomas should include grading of neoplasia according to the revised Vienna classification that has been modified for the European Guidelines to obtain a two-tiered system of low-grade and high-grade neoplasia (Table 1); see also Ref. [21]. This modified grading system aims to minimise intra- and inter-observer variation and facilitate management of endoscopically detected lesions by improving correlation between histopathology of biopsies and resection specimens [22]. Classically, adenomas are divided into tubular, tubulo-villous or villous types and demarcation between the three is based on the relative proportions of tubular and villous components, according to the “20% rule” described in the WHO classification of tumours in the digestive tract [23]. At least 20% of the estimated volume of an adenoma should be villous to be classified as a tubulo-villous adenoma and 80% villous to be defined as a villous adenoma. All other lesions are classified as tubular [23] (VI-A). The reproducibility of villousness increases when collapsing the categories into only two: tubular vs. any villous component (i.e. anything >20% villous). Adenomas can be endoscopically polypoid, flat or depressed. Due to the increased risk of colorectal cancer associated with flat and/or depressed lesions (III) they should be reported as non-polypoid lesions (see: “Non-polypoid adenomas”). The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions should be used to describe the gross appearance of colorectal adenomas (V-B). Key features to report in a programme are size, villousness, the grading of neoplasia, the recognition of invasion and features suggesting the need for further intervention either local or radical. The size of adenomas is important for their risk of containing an adenocarcinoma but it is also related to the need for subsequent surveillance, or colonoscopy.

Table 1.

Adaptation of the revised Vienna classification for colorectal cancer screening

| 1. No neoplasiaa |

| Vienna category 1 (negative for neoplasia) |

| 2. Mucosal low-grade neoplasia |

| Vienna category 3 |

| Mucosal low-grade neoplasia |

| Low-grade adenoma |

| Low-grade dysplasia |

| Other common terminology |

| Mild and moderate dysplasia |

| WHO: low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia |

| 3. Mucosal high-grade neoplasia |

| Vienna: category 4.1–4.4 |

| Mucosal high-grade neoplasia |

| High-grade adenoma/dysplasia |

| Non-invasive carcinoma (carcinoma in situ) |

| Suspicious for invasive carcinoma |

| Intramucosal carcinoma |

| Other common terminology |

| Severe dysplasia |

| High-grade intraepithelial neoplasia |

| WHO: high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia |

| TNM: pTis |

| 4. CARCINOMA invading the submucosa or beyond |

| 4a. Carcinoma confined to submucosa |

| Vienna: category 5 (Submucosal invasion by carcinoma) |

| TNM: pT1 |

| 4b. Carcinoma beyond submucosa |

| TNM: pT2-T4 |

The two-tiered grading of mucosal colorectal neoplasia recommended in the European Guidelines (see Table 1) is based on the revised Vienna Classification that has improved diagnostic reproducibility, particularly for non-polypoid lesions [24–28] (IV-B). The recommended two-tiered grading system also permits translation of histopathology findings of Western and Japanese pathologists into a uniform system for classification of colorectal neoplastic lesions.

In screening programmes the use of the term advanced adenoma has developed and is sometimes used to categorise adenomas for management. In this context an advanced adenoma is one that is either ≥10 mm or contains high-grade mucosal neoplasia or a villous component.

The hyperplastic polyp must be distinguished from other serrated lesions due to its extremely low malignant potential. The significance of other lesions in the serrated spectrum is controversial and our knowledge is still developing; traditional-serrated adenomas and mixed polyps with neoplasia should be considered as adenomas for the purpose of follow-up (surveillance). More details are provided in Ref. [11].

Measurement of size of adenomas

Size (largest diameter) is an important objective measurement best performed by the pathologist [29] from the slide, as is recommended in the EU guidelines for breast cancer screening [30]. Endoscopy measurements are less accurate and should only be used when strictly necessary (III-B). Pathology measurements are auditable, accurate, simple to perform and able to assess the size of the adenomatous component of mixed lesions. Although the quality of evidence is low, there are some indications that different modalities of advanced adenoma measurement (endoscopic measurement vs. pathologist’s measurement before and after fixation, on slide preparation) can affect diagnostic reproducibility and the detection rate of advanced adenomas. An overestimation or underestimation of a large or a small polyp is important when the misjudgement crosses the 10-mm threshold. It seems that the use of the pathologist’s measurement is currently the most accurate. If the lesion is too large for the maximum dimension to be measured by this method, because it cannot be represented on a single slide, the measurements taken at the time of specimen dissection should be used. If a biopsy is received or the specimen is fragmented it should be stated that it cannot be accurately assessed for size by the pathologist and the endoscopy measurements should be used. Measurements should exclude the stalk if it is composed of normal mucosa however the distance to the excision margin should be noted. The size of adenomas is used to determine the need for surveillance and therefore must be measured accurately to the nearest millimetre (and not rounded-up to the nearest 5 or 10 mm). Where the lesion is mixed or only part of a lesion is adenomatous, measurement should be performed on the adenomatous component. Programmes should have a policy on the methodology of, and should regularly monitor the accuracy of size measurements of endoscopically removed lesions. Deviation between the actual size and the measurements of pathologists and endoscopists should be minimised. Management decisions that depend on lesion size should take into account potential inaccuracy in the size measurement. The multidisciplinary team should consider deviating from the recommended size categories in treatment and surveillance algorithms, if the review of a case indicates that there is sufficient reason to doubt the accuracy of the measurement. Such cases should be captured as an auditable outcome (VI-B).

Tubular, tubulo-villous and villous adenomas: the typing of villousness

The 20% rule only applies to wholly excised polyps and to intact sections of lesions large enough to provide reliable proportions. For small fragmented lesions or superficial polyp biopsies, the presence of at least one clearly identifiable villus merits classification as “at least tubulo-villous”. Definitions of the types of villousness are presented in Ref [11].

Non-polypoid adenomas

The role of the pathologist in the evaluation of non-polypoid adenomas is to confirm the adenomatous nature of the lesion, and to determine the grade of neoplasia as well as the depth of depression in the case of a depressed non-polypoid lesion (see below). Since the expression “flat adenoma” is not well defined, it is recommended to group together all adenomatous lesions other than polypoid into the category of “non-polypoid adenomas” and avoid the term “flat”. Non-polypoid adenomas correspond to an endoscopical diagnosis of neoplasia in the subtypes IIa, IIb and IIc according to the Paris classification. Completely flat adenomas (type IIb) and depressed lesions (type IIc) are rarely found in the colon and rectum, while slightly elevated lesions (type IIa) are frequent. In the literature, the height of non-polypoid adenomas has been described histologically as not exceeding twice the height of normal mucosa, thus measuring less than 3 mm in height. This definition may be difficult to apply due to fixation artefacts and in slightly depressed lesions since the adjacent mucosa may be thinner than the normal epithelium. The endoscopic diagnosis of a non-polypoid lesion should be reported according to the Paris classification [21, 28, 31, 32] (III-B). We were unable to retrieve studies that specifically address the topic of the differences in the detection rates of non-polypoid colorectal neoplasms among the different types of screening programmes (FOBT vs. flexible sigmoidoscopy vs. total colonoscopy), although a prevalence of 9–10% of non-polypoid colorectal neoplasm (flat and depressed) was recently reported by Western pathologists in a large cross-sectional study [32]. Depressed lesions (type IIc) should be mentioned in the histological report for clinico-pathological correlation. Special care should be taken for centrally depressed lesions, especially when the depression is deeper than half of the adjacent lesion. These are reported to have a higher frequency of high-grade neoplasia and invasion at a smaller size than other flat or depressed lesions [21]. Non-polypoid adenomas can show so-called lateral spread with poor delineation of the margins thus making endoscopic removal difficult.

Serrated lesions

Terminology

These lesions have in common a serrated morphology, but depending on other characteristics, the potential to develop into invasive adenocarcinoma differs considerably. Serrated lesions vary from the hyperplastic polyp, which although relatively common, has no implications for the screening programme unless very numerous, proximally located or of a large size (>10 mm), to sessile-serrated lesions (sometimes referred to as sessile-serrated polyps/sessile-serrated adenomas), traditional-serrated adenomas, or mixed lesions/mixed polyps. Serrated lesions are infrequent, the evidence base is poor and recommendations are not well established, but until further evidence is forthcoming we recommend the following:

Hyperplastic (metaplastic) polyp

Hyperplastic polyps are often small lesions (<5 mm in diameter), frequently found in the left (distal) colon. They are composed of simple elongated crypts with a serrated structure in the upper half. These polyps usually show some proliferation in the basal (non-serrated) part of the crypts (regular proliferation). Nuclei are small, regular and basally orientated. There is no hyperchromasia, and stratification of the upper half of the crypts has a serrated appearance without cytological atypia.

Hyperplastic polyposis should be excluded in cases with giant hyperplastic polyps (>10 mm), or multiple hyperplastic polyps in the right colon, or in first-degree relatives of individuals with hyperplastic polyposis.

Sessile-serrated lesions

We recommend the use of the term sessile-serrated lesion for serrated lesions with structural alterations that do not show mucosal neoplasia. This term should replace the use of sessile-serrated polyp and sessile-serrated adenomas until better definitions are created.1 It is not recommended to use the latter terms in screening programmes because it would add additional ill-defined categories that may confuse practitioners.

Traditional-serrated adenomas

If the lesion shows a serrated morphology as well as mucosal neoplasia (cytological abnormalities), it is considered to be a traditional-serrated adenoma (TSA) [33]. It should be reported as such (TSA) and treatment and surveillance should be the same as for adenomas. For details see Ref. [11] as well as Chapter 9 of the EU guidelines (Colonoscopic surveillance after adenoma removal) [34]. This pragmatic recommendation recognises the neoplastic nature of these lesions. The non-serrated features found in such lesions (e.g. size and grade of neoplasia) and any co-existing pathology (e.g. number of neoplastic lesions) should be taken into account in selecting an appropriate surveillance protocol (VI-C).

Mixed polyp

These are lesions with combinations of more than one histopathologic type in the serrated spectrum (hyperplastic polyps, sessile-serrated lesions, traditional-serrated adenomas) or at least one type in combination with adenoma [35]. The important feature to recognise for the screening programme is the presence of neoplasia. The respective types of lesion in a mixed polyp should be reported and the term “mixed polyp” should only be used in brackets after the diagnosis of the individual components (e.g. adenoma and hyperplastic polyp, or traditional-serrated adenoma plus adenoma). Mixed polyps should be completely removed. If there is an adenomatous component, the lesion should be followed up (surveillance) in the same manner as for adenomas, taking into account the size and the grade of the adenomatous component (VI-C).

Grading of neoplasia

The revised Vienna classification has been adopted here, but in a simplified form suitable for screening and diagnosis, by removing the indefinite category between “negative for neoplasia” and “low-grade neoplasia”. This category has no clinical value and unlike inflammatory bowel disease is likely to be chosen very infrequently. Excluding it reduces the number of categories and simplifies the subsequent management choices. The advantages of the revised Vienna Classification on which the European screening classification is based are that it improves diagnostic reproducibility [24, 26–28] (IV-B). The modified format with a two-tiered grading of mucosal colorectal neoplasia aims to further reduce inter-observer variation [36] (IV-B). It encompasses the diagnostic categories used in the Eastern and the Western schools and each level has a clinical consequence. In the revised Vienna classification, the term neoplasia is used which is synonymous with the formerly used term “dysplasia”. In the two-tiered grading system recommended in the European Guidelines, mucosal low-grade neoplasia corresponds to neoplasia of the same grade in the revised Vienna classification; mucosal high-grade neoplasia likewise corresponds to neoplasia of the same grade in the revised Vienna classification. Invasive submucosal neoplasia in the European classification corresponds to carcinoma invading the submucosa or beyond in the Vienna classification (see Table 1).

Low-grade neoplasia

Low-grade neoplasia is an unequivocal neoplastic condition confined to the epithelial glands. It should not be mistaken for inflammatory or regenerative changes. Alterations characteristic for low-grade neoplasia start from one gland and develop into a microadenoma that then grows to become macroscopically visible. Caution should be exercised in patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease where the diagnosis of a neoplastic sporadic adenoma has implications different from that of neoplasia in colitic mucosa.

High-grade neoplasia

The changes of high-grade neoplasia should involve more than just one or two glands (except in tiny biopsies of polyps), and should therefore be identifiable at low-power examination. Caution should be exercised in over-interpreting isolated surface changes that may be due to trauma, erosion or prolapse.

High-grade neoplasia is diagnosed on structure, supplemented by an appropriate cytology. Hence, its presence is nearly always suspected by the low-power appearances where complex structural abnormalities are present in structures whose epithelium looks thick, blue, disorganised and with focal cell debris and necrosis.2 The structural features are:

Complex glandular crowding and irregularity (note that the word “complex” is important and excludes simple crowding of regular tubules that might result from crushing);

Prominent glandular budding;

A cribriform appearance and “back to back” glands; and

Prominent intraluminal papillary tufting.

While many of these features often coexist in high-grade neoplasia, individually they are neither necessary nor usually sufficient. Indeed they may occasionally occur in lower grades of neoplasia, and that is why it is necessary to further scrutinise the cytological features for signs of high-grade neoplasia. The cytological features of high-grade neoplasia are:

Loss of cell polarity or nuclear stratification. High-grade neoplasia should show at least 2–5 nuclear rows and preferably a variable number of rows within individual glands. The nuclei are haphazardly distributed within all three thirds of the height of the epithelium. No maturation of the epithelium is seen towards the luminal surface;

Neoplastic goblet cells (retronuclear/dystrophic goblet cells);

Cytology includes vesicular or/and irregular round nuclei with loss of polarity whereas spindle-like palisading nuclei are a sign of low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia;

Markedly enlarged nuclei, often with a dispersed chromatin pattern and a prominent nucleolus;

Atypical mitotic figures; and

Prominent apoptosis, focal cell debris and necrosis.

Again, these features usually coexist in high-grade neoplasia, and caution must be exercised in using just one. It should be emphasised again that they should occur in a background of complex structural abnormality. Marked loss of polarity and nuclear stratification sometimes occurs on the surface of small, structurally regular, tubular adenomas that otherwise have a lower grade of neoplasia, probably as a result of trauma, and must not be used to classify a lesion as high grade. The only exception to the rule is when the specimen consists of just a small biopsy from a polyp, when there is insufficient tissue to assess the architecture properly. In this situation it is permissible to label florid cytological abnormalities alone as high-grade neoplasia, but this will usually lead to re-excision of the whole polyp, when it will be possible to assess the whole lesion properly.

Also included within high-grade neoplasia is the presence of definite invasion into the lamina propria of the mucosa but not invasion through the mucscularis mucosae.

Other lesions

Inflammatory polyps

Experience from UK pilot sites has shown that inflammatory-type polyps are relatively common. Whilst they are most usually seen as a complication of chronic inflammatory bowel disease, particularly ulcerative colitis, they are also seen in association with diverticulosis, mucosal prolapse and at the site of ureterosigmoidostomy. Furthermore, sporadic, single inflammatory-type polyps (inflammatory cap polyp, cloacogenic inflammatory polyp, myoglandular polyp, granulation tissue polyp etc.) are well described in the colorectum. As the reporting pathologist may not know the true context of such polyps, we recommend that all such polyps be classified as “post inflammatory polyp”. The term inflammatory pseudopolyp (or even just “pseudopolyp”) should be avoided. Biopsies with mucosal prolapse syndrome should be identified and reported as such and not as neoplastic conditions.

Juvenile polyps

Juvenile polyps are spherical in shape, show an excess of lamina propria, and have cystically dilated glands. The expanded lamina propria shows oedema and mixed inflammatory cells. Experience from the UK faecal occult blood pilot sites suggests that occasional juvenile-type polyps are identified, even in the screening age group [37]. Juvenile polyps are most common in children but occasional examples are seen in adults. We advise that any polyp showing juvenile polyp-type features should be classified as “juvenile polyp” for the purposes of diagnostic reporting in a screening programme. Juvenile polyps often show epithelial hyperplasia but neoplasia is very rare. Single sporadic juvenile polyps have a smooth surface, can be found in all age groups and often are eroded. So-called atypical juvenile polyps show different morphological features, with a multilobated architecture, intact surface mucosa and (usually) a much more pronounced epithelial component. They are a characteristic feature of juvenile polyposis.

Peutz–Jeghers polyps

Whilst these polyps are usually seen in the Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, occasional examples are demonstrated as single, sporadic polyps in the colon. There remains uncertainty as to whether “inflammatory myoglandular polyp” represents a similar entity. As with juvenile polyposis, it would seem most unlikely, given the rarity of the syndrome and the age of the screening population, that Peutz–Jeghers syndrome would be diagnosed as part of a screening programme. Although Peutz–Jeghers polyps are classified as hamartomas, they have a very organised structure. They have a central core of smooth muscle with conspicuous branching, each branch being covered by colorectal-type mucosa that appears hyperplastic but not neoplastic. As with sporadic juvenile polyps, solitary Peutz–Jeghers-type polyps are most unlikely to demonstrate foci of neoplasia.

Serrated (hyperplastic) polyposis

This condition is characterised by one or more of the following conditions [38]:

At least five histologically diagnosed serrated polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon, of which two are >10 mm;

Any number of serrated polyps occurring proximal to the sigmoid colon in an individual who has a first-degree relative with hyperplastic polyposis; and/or

More than 30 serrated polyps of any size, but distributed throughout the colon.

As mentioned above (see: “Hyperplastic (metaplastic) polyp”), hyperplastic polyposis should be excluded in cases with giant hyperplastic polyps (>10 mm, hyperplastic polyps in the right colon or in first-degree relatives of individuals with hyperplastic polyposis).

Cronkhite–Canada syndrome

We believe it is most unlikely that such cases will present via a screening programme and the true diagnosis may not be recognised by pathological assessment. However, if Cronkhite–Canada syndrome is suspected, the pathologist should contact the endoscopist and ask for clinical details to ensure the diagnosis.

Neuroendocrine tumour

It is recommended to use the term “neuroendocrine tumour” rather than carcinoid in accordance with the WHO classification. These lesions are usually benign, small lesions and do not give rise to diagnostic difficulty.

Colorectal intramucosal tumours with epithelial entrapment and surface serration

Entrapment and pseudoinvasion of glands into the submucosal layer must be distinguished from invasive carcinoma. If in doubt, the relevant findings should be stated in the written report. If evaluation is problematic, step sections, a second opinion and further biopsies from the polypectomy ulcer should be considered.

Non epithelial polyps

Lipoma

Leiomyoma of the muscularis mucosae

Ganglioneuroma

Gastrointestinal schwannoma

Neurofibroma

GIST

Various forms of vascular tumour

Perineurioma

Fibroblastic polyp

Epithelioid nerve sheath tumour

Inflammatory fibroid polyp

Assessment of the degree of invasion of pT1 colorectal cancer

pT1 cancers are those showing invasion through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa but not into the muscularis propria.

Definition of invasion

We recommend the use of the WHO definition [23, 39] of an adenocarcinoma as an invasion of neoplastic cells through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa (VI-A). The term intramucosal carcinoma should be substituted by mucosal high-grade neoplasia according to the WHO classification and the modified classification of neoplasia recommended in the European Guidelines based on the revised Vienna classification (see Table 1). We recognise that this will not allow detailed comparison with Japanese series where, contrary to the previous US and European literature, a diagnosis of carcinoma can be made on cases of neoplasia without submucosal invasion, or even on the basis of marked intraepithelial atypia. The TNM classification [40–42] allows carcinoma in situ (Tis) but this does not improve on the revised Vienna classification and should not be used. Please see Ref. [11] for details (VI-B).

Careful consideration should be given to the potential for surgical overtreatment of misclassified early T1 cancers. Screening programmes require explicit criteria for the diagnosis and staging of early adenocarcinoma because unnecessary radical resection will raise the morbidity and mortality in colorectal cancer screening programmes. Please see annex [11] for further discussion of this point. Post-operative mortality (within 30 days) ranges between 0.6% and 4.4% in T1 cancers depending on the population, age of patient and quality of services available. Achieving the optimum balance between removing all disease by resection and minimising harm is very important.

Epithelial misplacement

Epithelial misplacement of adenomatous epithelium into the submucosa of a polyp is a well-recognised phenomenon [43]. It is commonly seen in prolapsing polyps in the sigmoid colon. Experience suggests that this will be one of the most difficult areas of pathological diagnostic practice in FOBT screening. Sigmoid colonic polyps are particularly prone to inflammation, a feature that tends to enhance the neoplastic changes present. When associated with epithelial misplacement, the potential for misdiagnosis of these lesions as early carcinoma become much greater. In cases of epithelial misplacement, surrounding lamina propria and haemosiderin-laden macrophages are found. Submucosal mucinous lakes may be seen. These do not warrant an immediate diagnosis of invasion and must be interpreted in association with the surrounding features.

High-risk pT1 adenocarcinoma

pT1 tumours provide many difficulties in a screening programme and the current evidence base for management of these lesions is poor and based on symptomatic patients [44–48] (V-B). With regard to the correlation between clinical outcomes and tumour pathology, a clear indication of an increased risk of residual disease, lymph-node metastasis, haematogenous metastasis, and mortality was observed after endoscopic polypectomy and subsequent surgical resection of poorly differentiated tumours (i.e. tumours with incomplete excision, poor grade of histological differentiation, venous and lymphatic invasion, tumour budding). Some pathology features, such as tumour budding and lymphatic and venous invasion appeared as possible prognostic factors for increased risk of lymph node metastasis but a clear guideline cannot be drawn as this correlation was not statistically significant in all studies. The available methods for substaging and differentiation grading are shown below. The most appropriate method depends on the morphology of the lesion and depth of invasion, e.g. non-polypoid-Kikuchi levels, and polypoid-Haggitt levels. In the future, more quantitative measurements should be investigated as suggested by the Japanese.

Substaging pT1

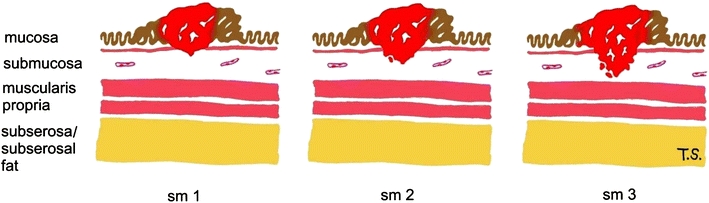

In pT1 tumours the frequency of lymph node metastasis in tumours that involve the superficial, middle and deep thirds of the submucosa, i.e. so-called Kikuchi levels sm1, sm2, and sm3 (Fig. 1) [49, 50] has been reported to be 2%, 8% and 23%, respectively [51].

Fig. 1.

Kikuchi levels of submucosal infiltration modified from Ref. [51]

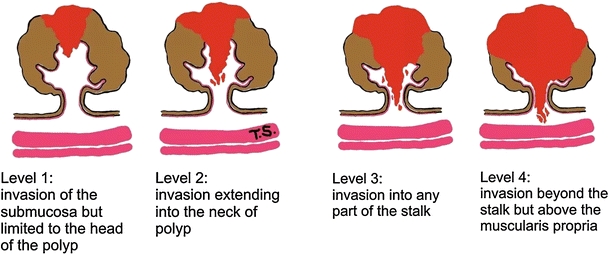

In pedunculated polypoid lesions, Haggitt identified the level of invasion into the stalk of the polyp (Fig. 2) as being important in predicting outcome and found that level 4 invasion, in which the tumour extended beyond the stalk of the polyp into the submucosa, but did not invade the muscularis propria, was an adverse factor [52].

Fig. 2.

Haggitt levels of invasion in polypoid carcinomas

However, both the Kikuchi (for non-polypoid tumours) and the Haggitt (for pedunculated tumours) systems may be difficult to use in practice, especially if there is fragmentation or suboptimal orientation of the tissue, and one study found lymph node metastases in six of 24 Haggitt level 3 lesions. More recently Ueno et al. [53] have proposed use of the depth (>2,000 μm) and width (>4,000 μm) of invasion measured in microns beyond the muscularis mucosae provides a more objective assessment of lymph node metastatic potential 2.5% vs. 18.2% when submucosal invasion width is < or ≥4,000 μm, respectively; and 3.9% vs. 17.1%, when submucosal invasion depth is < or ≥2,000 μm, respectively; and this approach has been adopted in Japan. Each classification has advantages and disadvantages.

Kikuchi cannot be used in the absence of muscularis propria; Haggitt is not applicable in non-polypoid lesions, and measurement depends on a recognisable submucosa from which to measure. In view of the uncertainty and lack of consensus, a firm evidence-based recommendation for one method of assessing local invasion cannot yet be made. At present we recommend the Kikuchi stage for non-polypoid lesions and Haggitt for pedunculated lesions (VI-C). All three approaches must be evaluated in further large series from multiple programmes to derive adequately evidence-based recommendations.

Tumour grade in pT1 lesions

Poorly differentiated carcinomas are identified by the presence of either irregularly folded, distorted and often small tubules or the lack of any tubular formation and showing marked cytological pleomorphism. In the absence of good evidence we recommend that a grade of poor differentiation should be applied in a polyp cancer when ANY area of the lesion is considered to show poor differentiation. Poor differentiation should equate to the WHO categories of poor and undifferentiated tumours [54]. The frequency should not exceed 20%. According to the WHO classification [39], budding of the tumour cells at the front of invasion should not influence grading of the tumour. Please see Ref. [11] for details.

Lymphovascular invasion in pT1 adenocarcinomas

Definite invasion of endothelium-lined vascular spaces in the submucosa is generally regarded as a significant risk for lymph node or distant metastasis. Sometimes retraction artefact around tumour aggregates can make assessment uncertain, in which case this uncertainty should be recorded and the observation should be interpreted in a multidisciplinary conference in the light of any other adverse histological features. At the moment there are no consistent data available on the additional use of immunohistochemistry, but this might be helpful in distinguishing retraction artefacts from lymphatic (e.g. LEM D 2–40) or capillary spread (e.g. CD 34).

Margin involvement in pT1 adenocarcinomas

It is important to record whether the deep (basal) resection margin is involved by invasive tumour (that may be a reason for further surgery) and whether the lateral mucosal resection margin is involved by carcinoma or the pre-existing mucosal neoplasia (in which case a further local excision may be attempted) (VI-B).

There has been considerable discussion and controversy in the literature over what degree of clearance might be regarded as acceptable in tumours that extend close to the deep submucosal margin [55]. It is important that clearance be measured and recorded in the report. All would agree that a clearance of 0 mm, and most would agree that a clearance of <1 mm is an indication for further therapy, others would use <2 mm. Currently, we recommend that clearance of 1 mm or less indicates margin involvement (VI-B). However, this may be handled by removal of any residual polyp endoscopically.

Tumour cell budding in pT1 adenocarcinomas

Tumour cell budding, i.e. the presence of small islands or single infiltrating tumour cells at the front of tumour invasion, has been described in the Japanese literature as an unfavourable prognostic factor if present in a marked degree [53, 56, 57]. Budding has been assessed either as slight, moderate or marked; or as present/absent [58, 59]. However, its reproducibility has been criticised, the diagnostic criteria vary [60] and the ability to predict metastasis compared to the previously discussed factors is unproven. Further research is needed in this area to identify the optimum method and its reproducibility before tumour cell budding can be recommended for routine use as an indicator of metastasis. Please see Ref [11] for details.

Site

The site of origin of each specimen should be individually identified by the clinician and provided to the pathologist on the request form (VI-B). This should preferably include both the segment of the bowel and the distance in cm from the anus. The pathologist should record this information on the proforma. This is important as the risk of lymph node metastases from a T1 adenocarcinoma has been reported to vary depending on the site of the lesion [61].

Specimen handling

Specimen handling is an important issue, as poor handling and dissection procedures can impair diagnostic accuracy. Specimen handling starts with the endoscopic removal of the specimen and ends with the histopathological diagnosis and report. The need for a close relationship between endoscopists and histopathologists is stressed.

Submission of specimens

It is recommended to place specimens in separate containers, one for each lesion, to avoid confusion about exact location; if lesions are small, individual cassettes or multicassettes can be used. Biopsies from the same lesion can be placed in the same container. For endoscopic resections it is helpful to pin out specimens by inserting pins through the periphery of the specimen onto cork or thick paper. Too much tension on the specimen could result in artificially thinned lesions. Needles should not be placed directly through a lesion but at the margin. Besides patient data, an exact description on location should be provided (e.g. cms from anocutanous line), as well as size and morphology (stalked polyp, non-polypoid—Paris classification, etc.). Additional information about central depression or focal erosion or ulceration or coexistent chronic inflammatory bowel disease can be useful. Endoscopic pictures can also be submitted with the specimen(s).

Fixation

Fixation should be by buffered 10% formalin; this equals a roughly 4% paraformaldehyde concentration, as formalin is 30–40% paraformaldehyde. Specimen(s) can shrink due to formalin fixation, therefore measurements taken after fixation can differ from those prior to fixation. Fixation in alcohol is not recommended and if any other fixatives are used a comparative study of size of adenomas after fixation should be performed prior to use to avoid excessive shrinkage of adenomas to avoid under treatment.

Dissection

The pathologist should verify the complete removal of neoplastic lesions (clear margins) and the absence of submucosal invasion in biopsy specimens. Currently, we recommend that clearance of 1 mm or less indicates margin involvement (VI-B). Cases of incomplete removal or uncertainty about submucosal invasion should be highlighted in the pathology report (VI-B). Lesion size should be given in millimetres. Size should be carefully measured identifying the maximum diameter of the adenomatous component as well as the distance to the margin of excision(s) to within a millimeter (V-B).

Given the small dimensions of the submucosal layer, infiltration into the submucosal level should be measured in microns from the bottom line of the muscularis mucosae (VI-B).

Polypoid lesions

Polyps must be sliced and totally embedded. Special attention should be paid to the resection margin, which should be identified and described (dot-like, broad, stalked etc.) and either dissected tangentially into an extra cassette or sliced in a way that allows complete assessment.

Mucosal excisions

Mucosal excisions need to be pinned out on a cork board or on another suitable type of material, fixed, described and dissected allowing the identification of involvement of the deep and lateral surgical margins. Particular attention should be paid to any areas of ulceration or induration for signs of invasion. Inking margins is recommended.

Piecemeal removal

If it is possible to reconstruct a lesion removed piecemeal it may be helpful but this is not commonly the case. It is good practice to embed the entire lesion to allow exclusion of invasive malignancy. Occasionally, whole embedding will not be possible.

Sectioning and levels

Three or more levels should be cut through each block and stained with haematoxylin and eosin.

Surgically removed lesions

Classification

The staging of colorectal cancer can be undertaken by a number of different systems. The two used in Europe are TNM and the older Dukes classification. Originally the Dukes classification system placed patients into one of three categories (stages A, B, C) (see Table 2). This system was subsequently modified by dividing stage C into stage C1 and C2 and the addition of a fourth stage (D). More recently, the Union Internationale Contra le Cancer (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has introduced the TNM staging system, that places patients into one of four stages (stages I–IV). TNM is superior to Dukes because of the greater information it yields, but there are currently major issues due to the periodic reclassification of this system that can lead to stage migration. TNM has a number of versions, so the version used should be noted in brackets (e.g. v5, v6, v7). Tables 3, 4 and 5 permit comparison of the most recent versions, 5, 6 and 7 [40–42]. However, there are differences between the versions, particularly regarding the notes on T and N classification. There is also variation between countries as to the TNM classification used. For example, TNM 5 is recommended in the UK, Holland, Belgium and Denmark and is growing in popularity in other countries.

Table 2.

Modified Dukes stage

| Dukes A | Tumour penetrates into but not through the muscularis propria (the muscular layer) of the bowel wall |

| Dukes B | Tumour penetrates into and through the muscularis propria of the bowel wall but does not involve lymph nodes |

| Dukes C | C1: There is pathological evidence of adenocarcinoma in one or more lymph nodes but not the highest node |

| C2: There is pathological evidence of adenocarcinoma in the lymph node at the high surgical tie | |

| Stage D | Tumour has spread to other organs (such as the liver, lung or bone) |

Table 3.

TNM classification of tumours of the colon and rectum

| Clinical classification | 5th edition (1997) | 6th edition (2002) | 7th edition (2009) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T—primary tumour | |||||

| TX | Primary tumour cannot be assessed | + | + | + | |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumour | + | + | + | |

| Tis1 | Carcinoma in situ: intraepithelial or invasion of lamina propria | + | + | + | |

| T1 | Tumour invades submucosa | + | + | + | |

| T2 | Tumour invades muscularis propria | + | + | + | |

| T3 | Tumour invades through muscularis propria into subserosa or into non-peritonealised pericolic or perirectal tissues | + | + | + | |

| T42,3 | Tumour directly invades into other organs or structures and/or perforates visceral peritoneum | + | + | + | |

| T4a | Perforates visceral peritoneum | – | – | + | |

| T4b | Directly invades other organ or structures | – | – | + | |

| N—regional lymph nodes | |||||

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | + | + | + | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | + | + | + | |

| N1 | Metastasis in 1 to 3 regional lymph nodes | + | + | + | |

| N1a | 1 node | – | – | + | |

| N1b | 2–3 nodes | – | – | + | |

| N1c | Satellites4 in subserosa, without regional nodes | – | – | + | |

| N2 | Metastasis in 4 or more regional lymph nodes | + | + | + | |

| N2a | 4–6 nodes | – | – | + | |

| N2b | 7 or more nodes | – | – | + | |

| M—distant metastasis | |||||

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed | + | + | – | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis | + | + | + | |

| M1 | Distant metastasis | + | + | + | |

| M1a | Metastasis confined to one organ (liver, lung, ovary, non-regional lymph node(s)) | – | – | + | |

| M1b | Metastasis in more than one organ or the peritoneum | – | – | + | |

Table 4.

TNM stage grouping of tumors

| Stage | Stage grouping | 5th Edition (1997) | 6th Edition (2002) | 7th Edition (2009) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | N | M | ||||

| Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | + | + | + |

| Stage I | T1,T2 | N0 | M0 | + | + | + |

| Stage II | T3,T4 | N0 | M0 | – | – | + |

| Stage IIA | T3 | N0 | M0 | + | + | + |

| Stage IIB | T4 | N0 | M0 | + | + | – |

| Stage IIB | T4a | N0 | M0 | – | – | + |

| Stage IIC | T4b | N0 | M0 | – | – | + |

| Stage III | Any T | N1, N2 | M0 | – | – | + |

| Stage IIIA | T1,T2 | N1 | M0 | + | + | + |

| Stage IIIA | T1,T2 | N1c | M0 | – | – | + |

| Stage IIIA | T1 | N2a | M0 | – | – | + |

| Stage IIIB | T3,T4 | N1 | M0 | + | + | – |

| Stage IIIB | T3,T4a | N1/N1c | M0 | – | – | + |

| Stage IIIB | T2,T3 | N2a | M0 | – | – | + |

| Stage IIIB | T1,T2 | N2b | M0 | – | – | + |

| Stage IIIC | Any T | N2 | M0 | + | + | – |

| Stage IIIC | T4a | N2a | M0 | – | – | + |

| Stage IIIC | T3,T4a | N2b | M0 | – | – | + |

| Stage IIIC | T4b | N1, N2 | M0 | – | – | + |

| Stage IV | Any T | Any N | M1 | + | + | – |

| Stage IVA | Any T | Any N | M1a | – | – | + |

| Stage IVB | Any T | Any N | M1b | – | – | + |

T tumour, N node, M metastasis

Table 5.

Notes

| No. | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5th edition | 6th edition | 7th edition | |

| 1 | Tis includes cancer cells confined within the glandular basement membrane (intraepithelial) or lamina propria (intramucosal) with no extension through muscularis mucosae into the submucosa. Note: the authors of the European Guidelines for quality assurance in pathology in CRC screening and diagnosis recommend not using this category. Respective lesions should be reported as mucosal high-grade neoplasia, see above (“Grading of neoplasia”) | ||

| 2 | Direct invasion in T4 includes invasion of other segments of the colon or rectum by way of the serosa, e.g. invasion of sigmoid colon by a carcinoma of the cecum | Direct invasion in T4b includes invasion of other organs or segments of the colon or rectum by way of the serosa, as confirmed on microscopic examination, or for tumours in a retroperitoneal or subperitoneal location, direct invasion of other organs or structures by virtue of extension beyond the muscularis propria | |

| 3 | Tumour that is adherent to other organs or structures, macroscopically, is classified T4. However, if no tumour is present in the adhesion, microscopically, the classification should be pT3 | Tumour that is adherent to other organs or structures, macroscopically, is classified cT4b. However, if no tumour is present in the adhesion, microscopically, the classification should be pT1–T3, depending on the anatomical depth of wall invasion | |

| 4 | A tumour nodule greater than 3 mm in diameter in perirectal or pericolic adipose tissue without histological evidence of a residual lymph node in the nodule is classified as regional lymph node metastasis. However, a tumour nodule up to 3 mm in diameter is classified in the T category as discontinuous extension i.e. T3. | A tumour nodule in the pericolic/perirectal adipose tissue without histological evidence of a residual lymph node in the nodule is classified in the pN category as a regional lymph node metastasis if the nodule has the form and smooth contour of a lymph node. If the nodule has an irregular contour it should be classified in the T category and also coded as V1 (microscopic venous invasion) or V2, if it was grossly evident, because there is a strong likelihood that it represents venous invasion | Tumour deposits (satellites), i.e. macroscopic or microscopic nests or nodules, in the pericolorectal adipose tissue’s lymph drainage area of a primary carcinoma without histological evidence of residual lymph node in the nodule, may represent discontinuous spread, venous invasion with extra-vascular spread (V1/2) or a totally replaced lymph node (N1/2). If such deposits are observed with lesions that would otherwise be classified as T1 or T2, then the T classification is not changed, but the nodule is recorded as N1c. If a nodule is considered by the pathologist to be a totally replaced lymph node (generally having a smooth contour), it should be recorded as a positive lymph node and not as a satellite, and each nodule should be counted separately as a lymph node in the final pN determination. (Note of the authors of the European Guidelines for quality assurance in pathology in CRC screening and diagnosis: introduction of N1c category leads to stage shift from II to III for some tumours) |

In the USA, version 7 is used. TNM 7 appears to be more subjective than TNM 5 due to the notes on N classification and the category N1c, promoting stage migration from II to III [62–64]. National results should be reported with the version of TNM used in a given country (VI-B).

Practical issues

High-quality reporting of colorectal cancer is very important both to the clinicians treating the patients and to the cancer registry. The introduction of a ‘minimum’ data proforma template allows more complete reporting compared with interpretation of free text reports by medical staff [65–72]. All biopsies and lesions identified in the screening programme and the subsequent resection specimens should be reported on a paper or electronic proforma (II-B) in a timely manner and in a minimum of 90% of all cases. The proforma should be sent to the referring physician, the relevant cancer registry and the screening programme (VI-B).

Dissection should be according to national guidelines such as those for the UK; Royal College of Pathologists [73–75] and the NHS Bowel Cancer Screening publication [76], the Scottish clinical guidelines [77], the Dutch guidelines [78, 79], the German guidelines [80] or the Italian guidelines [81]. For examples of these guidelines see the list of websites in Appendix 4 of the full guideline document [9]. If national guidelines do not exist they should be created or adopted from elsewhere (VI-B). An additional free text written report is optional, but needs to include all of the data required in the proforma (VI-B).

Pathologists need access to a high-quality, binocular microscope with at least the following objectives: 5×, 10×, 20× and 40× and that fulfils national guidelines such as those of the Sector Committee for Pathology and Neuropathology of the German Accreditation Body [82]

A computer is required for identifying previous material from a given patient and for filling in proformas electronically and online if secure online services are available. Adequate time must be available for dissection, reporting, and attendance at meetings of the screening team and the colorectal cancer multidisciplinary team (VI-B). Time and funding are required for pathologists to attend national meetings on the screening programme and continued training in histopathology of colorectal neoplasia. Pathologists should attend one refresher training course every year on the pathology of colorectal neoplasia to maintain quality (VI-B).

Standards and quality indicators

There should be good communication between members of the screening team with agreed terminology, regular meetings and clinical discussions (VI-B).

An external quality assurance programme should be put in place, specifying a minimum of two slide circulations per year of an adequate number of slides (VI-B). This may be via clusters or cells of pathologists using glass slides, or can be electronic using images or virtual slides [83] distributed via DVD or the web (see http://www.virtualpathology.leeds.ac.uk). There should be external oversight of such programmes. In the absence of evidence-based guidelines we recommend that pathologists reporting in a colonoscopy programme should not report high-grade neoplasia in more than 5% of lesions and those in an FOBT programme in not more than 10% of lesions (VI-B).

The pathologists reporting in the programme must meet their national criteria for safety in reporting colorectal cancer (VI-B). Departments and pathologists taking part in screening programmes should audit their own reporting practices for key features, including the number of lymph nodes retrieved, the frequency of circumferential resection margin involvement (CRM) and the frequency of high-risk features such as extramural vascular invasion and peritoneal invasion reported (VI-B). In the UK, national standards suggest that the number of nodes retrieved should be above a median of 12, CRM positivity in rectal cancer should be below 15%, extramural vascular invasion reported in more than 25%, and peritoneal invasion in more than 20%. The laboratory must be able to demonstrate participation in a laboratory technical external quality assurance programme, such as Clinical Pathology Accreditation UK (http://www.cpa-uk.co.uk/), the ISO/IEC accreditation developed by the Sector Committee for Pathology and Neuropathology of the German Accreditation Body (http://www.dakks.de/, see also Ref. [84]), or other national standards (VI-C).

Data collection and monitoring

Lesions reported in the screening programme should be reported by proforma (II-B) or structured reporting, and the data returned to the screening programme or national tumour registries. This will include all lesions identified and the subsequent resection specimen. This should occur in a minimum of 90% of all cases (VI-B).

Studies have shown discrepancy between the histopathology of biopsies and total removal by polypectomy, EMR and surgical specimens. Colorectal cancer was detected in surgical specimens in over 20% of biopsies diagnosed with high-grade neoplasia [85]. Sub-mucosal invasion was detected in surgical specimens in over 25% of cases with mucosal neoplasia [22]. Therefore, the correlation between histological diagnosis of biopsies and resections should be reported. Any lack of correlation should be discussed by the multidisciplinary team and the results of this discussion should be documented (III-B).

Pathologists must ensure that their proformas are received by the screening programme coordinators or a cancer registry for the purposes of clinical management, audit and quality assurance (VI-B).

Results from the key indicators of quality should be returned for analysis to the funding body: either the Health Authority or the national screening programme’s offices (VI-B).

Statistics should include the frequency of colorectal cancer and the distribution of TNM stages and version used; as well as the distribution of the type of lesion, size, location, frequency of grades of dysplasia and villousness (villous, tubulo-villous or tubular) and presence of non-neoplastic lesions (VI-B).

Images

A selection of images and digital slides showing the histopathology of lesions commonly detected in screening programmes, as well as some images illustrating pitfalls in histopathologic interpretation is provided in the internet at http://www.virtualpathology.leeds.ac.uk (go to: “European Guidelines for quality assurance in pathology in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis—Imaging library”). The site has been created to establish an initial, quality-assured repository for images illustrating the chapter on pathology in the first guideline edition [10]. The images are provided here for reference and have been reviewed by pathologists from at least three European countries. We encourage colleagues to submit further images which they feel could be instructive or otherwise useful in illustrating or further developing the European Guidelines.

We also aim to extend the scope of this site in the future to promote pan-European and international collaboration in training and in expanding the evidence base for further advances in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis.

Conclusions and recommendations

In a state-of-the-art process, wide consensus has been achieved on the following evidence-based recommendations for quality assurance of pathology in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. In light of the experience with similar guidelines for breast and cervical cancer screening in the EU, the future availability of this reference document has the potential to improve multidisciplinary management of colorectal cancer detected within and outside the setting of screening programmes. The availability of a uniform classification for reporting lesions detected in screening programmes across Europe also has the potential to improve international collaboration and exchange of experience in improving the quality and effectiveness of colorectal cancer care.

Due to the improved diagnostic reproducibility of the revised Vienna classification use of this classification in a format modified for lesions detected in screening is recommended to ensure consistent international communication and comparison of histopathology of biopsies and resection specimens (IV-B). Only two grades of colorectal neoplasia (low grade and high grade) should be used, to minimise intraobserver and interobserver error (V-B). The terms intramucosal adenocarcinoma or in-situ carcinoma should not be used (VI-B).

The World Health Organisation (WHO) definition of colorectal adenocarcinoma should be used: “an invasion of neoplastic cells through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa” (VI-A).

Adenocarcinomas should be reported according to the tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) classification. The version of TNM to be used should be decided nationally and should be stated e.g. pT1 pN0 pMX (Version 5) or pT4 pN2 pM1 (Version 7). These can be further abbreviated to pT1N0MX (v5) or to pT4N2M1 (v7) (VI-B).

The WHO classification of adenomas into tubular, tubulo-villous and villous should be used (VI-A).

Due to the increased risk of colorectal cancer associated with flat and/or depressed lesions they should be reported as non-polypoid lesions (III) and further classified by the Paris classification (V-B).

The pathologist should verify the complete removal of neoplastic lesions (clear margins) and the absence of submucosal invasion in biopsy specimens. Currently we recommend that clearance of 1 mm or less indicates margin involvement (VI-B). Cases of incomplete removal or uncertainty about submucosal invasion should be highlighted in the pathology report (VI-B).

Substaging of T1 cancers should be performed to determine the risk of residual disease. Consideration should be given to the appropriate method, which may vary depending on the morphology of the lesion (Kikuchi/Haggitt or measurement). For non-polypoid lesions the Kikuchi stage and for pedunculated lesions Haggitt are currently recommended (VI-C). High-risk features for residual disease such as lack of margin clearance (≤1 mm), poor differentiation and lymphatic and vascular invasion should be reported (V-B). The multidisciplinary team should be consulted on whether or not surgical resection of pT1 adenocarcinoma is recommended; if surgical resection is recommended, consideration should be given to obtaining an opinion from a second histopathologist as variation exists in evaluating high-risk features (VI-A).

The size of lesions should be carefully measured by the pathologist to the nearest mm on the haematoxylin and eosin slide, or on the fixed specimen when the largest dimension of the lesion cannot be reliably measured on the slide. Endoscopy measurements are less accurate and should only be used when strictly necessary, e.g. if the lesion is fragmented (III-B). Given the small dimensions of the submucosal layer, infiltration into the submucosal level should be measured in microns from the bottom line of the muscularis mucosae (VI-B).

Programmes should have a policy on the methodology of, and should regularly monitor the accuracy of size measurements of endoscopically removed lesions. Deviation between the actual size and the measurements of pathologists and endoscopists should be minimised. Management decisions which depend on lesion size should take into account potential inaccuracy in the size measurement. The multidisciplinary team should consider deviating from the recommended size categories in treatment and surveillance algorithms, if the review of a case indicates that there is sufficient reason to doubt the accuracy of the measurement. Such cases should be captured as an auditable outcome (VI-B).

Hyperplastic polyps are non-neoplastic and their complete removal is optional. All other lesions in the serrated pathway should be excised and serrated lesions with neoplasia should be followed up (surveillance) as if they were adenomas (VI-C).

All biopsies and lesions identified in the screening programme and the subsequent resection specimen should be reported on a proforma (IV-B) in a timely manner and in a minimum of 90% of all cases. The proforma should be sent to the referring physician, the relevant cancer registry and the screening programme (VI-B).

Dissection of all specimens should be according to national guidelines. If national guidelines do not exist they should be created or adopted from elsewhere. An additional free text written report is optional, but must include all of the data required in the proforma (VI-B).

The correlation between histological diagnosis of biopsy and surgical specimens should be reported. Any lack of correlation should be discussed by the multidisciplinary team, and the results of this discussion should be documented (III-B).

Pathologists must ensure that their proformas are received by the screening programme coordinators or a cancer registry for the purposes of clinical management, audit and quality assurance. Results from the key indicators of quality should be returned to the funding body: either the Health Authority or the national screening programmes’ offices for analysis (VI-B).

Statistics should include the frequency of colorectal cancer and the distribution of TNM stages and version used, as well as the distribution of the type of lesion, size, location, frequency of grades of neoplasia and villousness (villous, tubulo-villous or tubular) and presence of non-neoplastic lesions (VI-B).

There should be good communication between the members of the screening team with agreed terminology, regular meetings and clinical discussions (VI-B).

Pathologists taking part in a colorectal cancer screening programme must participate regularly in multidisciplinary team meetings, and twice a year in an external quality assurance programme that has external oversight of the results (VI-B).

Departments and individual pathologists should audit their own reporting practices for key features (VI-B).

Pathologists reporting in a colorectal cancer screening programme must meet their national criteria for safety in reporting colorectal cancer (VI-B).

Departments and pathologists taking part in screening programmes should audit the number of lymph nodes retrieved, the frequency of circumferential resection margin involvement and the frequency of high-risk features such as extramural vascular invasion, tumour perforation and peritoneal invasion reported (VI-B).

Pathologists reporting in a colonoscopy screening programme should not report high-grade neoplasia in more than 5% of lesions and those in an Faecal Occult Blood Test programme in not more than 10% of lesions (VI-B).

Pathologists should attend one refresher training course every year on the pathology of colorectal neoplasia to maintain quality (VI-B).

Laboratories participating in a screening programme must be able to demonstrate participation in a laboratory technical external quality assurance programme and hold external accreditation for their services (VI-C).

Further detailed information can be found in Ref. [11].

Acknowledgements

Some of the materials contained in these guidelines is reproduced with permission of the UK bowel cancer screening programme pathology screening committee (Carey F, Mapstone N, Quirke P (Chair), Shepherd N, Warren B, Williams G) and the Royal College of Pathologists minimum dataset for colorectal cancer reporting (Williams G, Quirke P, Shepherd N).

We thank the following external reviewers for reading and providing helpful comments and suggestions on the draft chapter and annex on Quality assurance in pathology in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis during the preparation of the full guidelines document: Robert Riddell, Toronto, Canada; Hiroshi Saito, Tokyo and Hidenobu Watanabe, Niigata, Japan.

The comments and suggestions received from consultation of the European Cancer Network are gratefully acknowledged.

Phil Quirke is supported by Yorkshire Cancer Research and the Department of Health/Cancer Research UK Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre Initiative

Financial support of the European Communities through the EU Public Health Programme (Development of European Guidelines for Quality Assurance of Colorectal Cancer Screening lCRC), grant agreement No. 2005317), of the Public Affairs Committee of the United European Gastroenterology Federation, and from a cooperative agreement between the American Cancer Society and the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is gratefully acknowledged.

The technical support of Tracy Lignini, Krittika Guinot and Simon Ducarroz at the International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France, in the preparation of the manuscript and the assistance of Dr. Tilman Schulz, Bayreuth, Germany, in the creation of illustrations is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of interest

Pathology and Tumour Biology at the Leeds Institute of Molecular Medicine, led by Phil Quirke, at the University of Leeds has received funding from the EU Public Health Programme (Development of European Guidelines for Quality Assurance of Colorectal Cancer Screening (CRC), grant agreement No. 2005317) to develop a prototype web-based training tool for pathology in colorectal cancer screening. Phil Quirke has also received funding from the National Health Service Bowel Cancer Screening Programme and Yorkshire Cancer Research.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer, where Lawrence von Karsa is employed, is a recipient of research grants from the EU Public Health Programme.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

The term sessile-serrated polyp has been proposed elsewhere for serrated lesions that cannot be definitely classified into the category of hyperplastic polyps or serrated adenomas [12], especially in cases with technical inconsistencies such as tangential cuts or superficial biopsies. The same terminology has been propsed for lesions with minimal and focal structural alterations in the absence of cytological atypia [86].

High-grade neoplasia also contains the subgroup of intramucosal carcinoma used by some pathologists but not recommended here. For details see Ref. [11].

References

- 1.von Karsa L, Anttila A, Ronco G, Ponti A, Malila N, Arbyn M, Segnan N, Castillo-Beltran M, Boniol M, Ferlay J, Hery C, Sauvaget C, Voti L, Autier P (2008) Cancer screening in the European Union—Report on the implementation of the Council Recommendation on cancer screening, First Report. European Commission, Luxembourg

- 2.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [Internet] Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, Moss SM, Amar SS, Balfour TW, James PD, Mangham CM. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1472–1477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jorgensen OD, Sondergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1467–1471. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, Snover DC, Bradley GM, Schuman LM, Ederer F. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota colon cancer control study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(19):1365–1371. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305133281901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Council of the European Union (2003) Council recommendation of 2 December 2003 on cancer screening (2003/878/EC). Off J Eur Union (L 327):34–38

- 7.Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C, Tornberg S, Holland R, von Karsa L, editors. European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. 4. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screening - Second Edition. Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J, Schenck U, Ronco G, Segnan N, Wiener H, Herbert A, Daniel J, von Karsa L (eds) (2008) European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening—Second Edition. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. Segnan N, Patnick J, von Karsa L (eds) (2010) European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis - First edition (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Quirke P, Risio M, Lambert R, Vieth M (2010) Quality assurance in pathology in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis. In: Segnan N, Patnick J, von Karsa L (eds) European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Colorectal Cancer Screening and Diagnosis - First edition (in press)

- 11.Vieth M, Quirke P, Lambert R, von Karsa L, Risio M (2010) Annotations of colorectal lesions. In: Segnan N, Patnick J, von Karsa L (eds) European guidelines for quality assurance in colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis - First edition (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]