Abstract

Leaf dark respiration (R) is an important component of plant carbon balance, but the effects of rising atmospheric CO2 on leaf R during illumination are largely unknown. We studied the effects of elevated CO2 on leaf R in light (RL) and in darkness (RD) in Xanthium strumarium at different developmental stages. Leaf RL was estimated by using the Kok method, whereas leaf RD was measured as the rate of CO2 efflux at zero light. Leaf RL and RD were significantly higher at elevated than at ambient CO2 throughout the growing period. Elevated CO2 increased the ratio of leaf RL to net photosynthesis at saturated light (Amax) when plants were young and also after flowering, but the ratio of leaf RD to Amax was unaffected by CO2 levels. Leaf RN was significantly higher at the beginning but significantly lower at the end of the growing period in elevated CO2-grown plants. The ratio of leaf RL to RD was used to estimate the effect of light on leaf R during the day. We found that light inhibited leaf R at both CO2 concentrations but to a lesser degree for elevated (17–24%) than for ambient (29–35%) CO2-grown plants, presumably because elevated CO2-grown plants had a higher demand for energy and carbon skeletons than ambient CO2-grown plants in light. Our results suggest that using the CO2 efflux rate, determined by shading leaves during the day, as a measure for leaf R is likely to underestimate carbon loss from elevated CO2-grown plants.

Photosynthesis and mitochondrial respiration (also referred to as dark respiration, as opposed to photorespiration) are metabolic pathways that produce ATP and reductants to meet energy demands for plant growth and maintenance. Although the light reaction in photosynthesis provides ATP and reductants for biosynthesis in a leaf cell during illumination, mitochondrial respiration in light is necessary for biosynthetic reactions in the cytosol, such as sucrose synthesis (1, 2). Respiratory activity in light can even be considered part of the photosynthetic process, because it is needed to regulate the state of stromal redox during photosynthesis (3) and to maintain the cytosolic ATP pool (1). Mitochondrial respiration might also be a source for biosynthetic precursors, such as acetyl-CoA or acetate for chloroplastic fatty acid synthesis in light (1). The required magnitude of mitochondrial respiration in light is therefore determined by the potential need for this process to provide energy and carbon skeletons in the light (2).

Mitochondrial respiratory activity during illumination varies between 25 and 100% of the respiratory activity in darkness (1). The lower rate of nonphotorespiratory mitochondrial CO2 release during illumination has been interpreted as evidence for partial inhibition of leaf respiration by light (4–6). The magnitude of light inhibition of respiration seems to depend on the photosynthetic capacity (1), but the mechanism of light regulation of mitochondrial respiration is not clearly understood (2, 3). Although there has been much study of, albeit little agreement on, the effects of elevated CO2 on plant respiration (7–9), the effects of elevated CO2 on mitochondrial respiration in light have been little studied and hence are largely unknown (5, 10). The commonly used method for estimating daytime leaf respiration as affected by CO2 concentration is measurement of the rate of CO2 efflux by shading leaves during the day (8, 11). However, light inhibition of mitochondrial respiration found in a variety of species (6, 12, 13) calls into question the validity of this method, because it assumes leaf respiration continues at the same rate in the light as in darkness. Leaf dark respiration is an important component in plant carbon balance and can return as much as 40–50% of photosynthetically fixed carbon to the atmosphere (14, 15). It is therefore essential that we understand whether light has a differential effect on dark respiration of ambient and elevated grown CO2 plants to more accurately estimate the extent of respiratory carbon loss in terrestrial ecosystems as atmospheric CO2 rises.

Three types of dark respiration were studied in our experiment: leaf respiration in light estimated by using the Kok method during the day (RL), leaf respiration in darkness measured as rate of CO2 release by shading leaves during the day (RD), and leaf dark respiration at the end of the dark period (RN). Our primary objective was to study the effects of elevated CO2 on leaf RL at different developmental stages of Xanthium strumarium, especially before and after flowering. We hypothesized that leaf RL would be higher at elevated CO2 than at ambient CO2, because plants grown at elevated CO2 produce more biomass (16, 17), and higher biomass production requires a higher demand for ATP, reductants, and biosynthetic precursors. Our secondary objective was to investigate whether leaf RN had similar responses to CO2 enrichment as leaf RL or RD. We also examined the relationship between photosynthetic rate at saturated photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) [net photosynthesis at saturated light (Amax)] and respiration, two biological processes that link organic carbon in the biosphere with inorganic carbon in the atmosphere. Our study will therefore help to elucidate the mechanisms of higher atmospheric CO2 effects on plant respiration and to construct a more accurate carbon budget of plants under elevated CO2.

Materials and Methods

Growth Conditions.

We grew X. strumarium L. (common cocklebur), a developmentally determinate cosmopolitan species, in environmentally controlled conditions. X. strumarium is a qualitative short-day plant that flowers only when days are shorter than 15.7 h and nights are longer than 8.3 h (18). Seeds of X. strumarium were obtained from a single seed source in Lubbock, TX. Plants were germinated and grown in 8.4-liter pots filled with sand in four 1.4-m2 growth chambers (Conviron, Controlled Environments, Winnipeg, MB, Canada) at the Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory. To examine the possible effects of developmental stage on plant respiratory responses to elevated CO2, six cohorts were planted at 5-day intervals starting November 23, 1999. After germination, seedlings were thinned to one for each pot. Carbon dioxide concentrations were maintained at 730 μmol mol−1 in two chambers (elevated CO2 treatment) and at 365 μmol mol−1 in the other two chambers (ambient CO2 treatment). The elevated CO2 treatment was created by adding pure CO2 to a mixing fan within the chambers. Air temperature was maintained at 28/20°C (day/night) and relative humidity at 50%. PAR was approximately 300–400 μmol m−2 s−1 at leaf surface for the photoperiod from 09:00 to 03:00 h during the entire growing period. Flowering was induced by changing the photoperiod from 18 h to 12 h on January 11, 2000, when the youngest plants were approximately 3 weeks old. Photoperiod was changed back to 18 h 2 days later, and the 18-h photoperiod was maintained for the rest of the experiment. All of the plants started flowering on January 23, 2000, regardless of planting dates. All pots were watered to saturation daily with distilled water throughout the experiment. Soil nutrients were supplemented by adding Osmocote Plus (15–11-13, 90269, Scotts–Sierra Horticultural Products, Marysville, OH). The experimental design was a complete factorial with six replicates per treatment for a total of 72 plants (two CO2 levels × six planting dates × six replicates).

Gas-Exchange and Leaf Nitrogen Measurements.

Leaf photosynthetic rate (A) was measured by using a LI-6400 Portable Photosynthesis System (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE) on the youngest mature leaves. Leaf A was first measured at saturating PAR of 1,500 μmol m−2 s−1 (Amax) and then at lower levels of PAR (100, 80, 60, 40, 30, 20, 10, 0, 0, 0 μmol m−2 s−1) at growth CO2. Leaves were allowed to equilibrate for at least 5 minutes at each light level before any reading was recorded. Leaf temperature was maintained at 27.3 ± 0.05°C (mean ± SE) and relative humidity at ≈50% inside the cuvette.

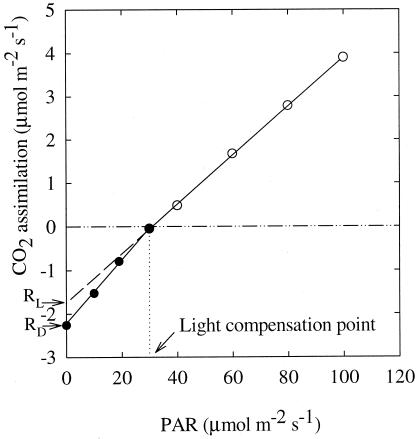

The Kok (19) and Laisk methods (20) are the most commonly used methods for estimating leaf respiration in light. We chose the Kok method, because the Laisk method is not appropriate for studying the effect of different CO2 concentrations on leaf RL, as intercellular CO2 concentration would have to be changed during the course of the measurement (6). Photosynthetic rates at low light levels were plotted against the eight PAR levels (Fig. 1). There was an obvious change in the slope of the line near the light compensation point (the Kok effect). The upper part of the light curve, before the obvious change in slope, was extended to the axis of A, and the intercept was considered to be leaf RL under growth conditions (19). Leaf RD was obtained by averaging the three CO2 efflux rates at zero PAR for each plant, which was equal to the intercept of the lower part of the curve at the axis of A (Fig. 1). Leaf RN was measured at the end of the daily dark period, i.e., from 07:00 to 09:00 h, by using the same Photosynthesis System. After stable CO2 flow was achieved, three readings were recorded at a 30-s interval, and the average was taken as leaf RN. Leaf temperature was 20.0 ± 0.05°C during the measurement of leaf RN.

Figure 1.

Representative photosynthetic light-response curve of X. strumarium at low PAR. The CO2 efflux rate at PAR = 0 was considered to be daytime leaf mitochondrial respiration in darkness (RD). The part of light-response curve before the abrupt change in slope was extended to y axis, and the intercept was considered to be daytime leaf mitochondrial respiration in light (RL) according to Kok (19). Change in slope of the curves occurs near the light compensation point.

After the last set of gas-exchange measurements, all plants were harvested. Leaf samples were collected for leaf nitrogen assay. Leaf N concentration was determined in dried and ground material by using an NCS autoanalyzer (Carlo Erba NCS 2500, Milan, Italy).

Statistical Analysis.

Data were analyzed by using a two-way analysis of variance with CO2 treatment and planting date as the main effects and chamber as a nested effect within CO2 treatment by using spss (Ver. 10.0.2, SPSS, Chicago). Measurements from different plants sowed at the same time in each chamber were averaged before being analyzed, because planting date did not have a significant effect on these measurements. Comparisons among means for CO2 levels and planting dates were made by least significant difference for a priori comparisons. Treatment effects were considered to be significant if P < 0.05.

Results

Daytime Leaf RD and RL.

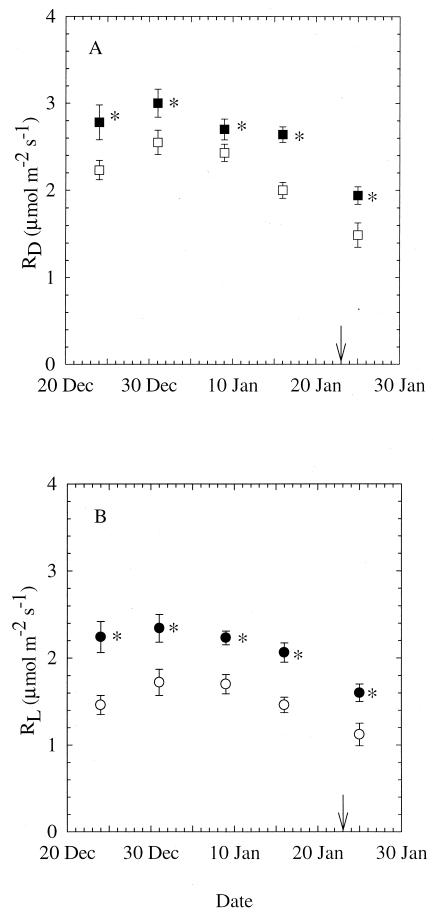

Leaf RD and RL were significantly higher in elevated CO2 compared with ambient CO2-grown plants throughout the experiment (P < 0.05; Fig. 2). The difference in daytime leaf R between plants grown at ambient CO2 and elevated CO2 concentration ranged from 11 to 32% for leaf RD and 31 to 53% for leaf RL. There was a gradual decrease of both leaf RD and RL as plants grew in size, although there was no significant effect of planting date on any particular measuring date. After flowering initiation, leaf RD and RL dropped ≈30% from their preflowering levels in ambient as well as in elevated CO2-grown plants.

Figure 2.

Leaf RD (A) and leaf RL (B) of X. strumarium grown at ambient (open symbols) or elevated (closed symbols) CO2. Leaf RD and RL were measured at growth CO2 concentration on five different dates. Because there was no effect of planting date on RD or RL, all measurements from plants of different ages were averaged for each CO2 treatment. Arrow indicates date of flowering for all plants. Mean ± 1 SE; n = 18 for December 24, 1999, and n = 24 for all other dates. *, P < 0.05.

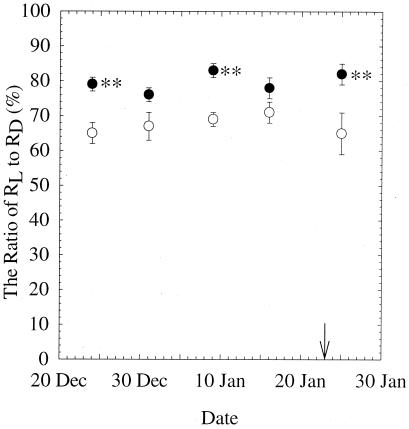

Elevated CO2-grown plants had significantly higher leaf RL/RD ratio than ambient CO2-grown plants on three measuring dates (P < 0.01). The ratio of leaf RL to RD, which reflects the magnitude of inhibition of daytime leaf dark respiration by light, remained remarkably constant during the experiment (Fig. 3). The ratio of RL/RD was marginally higher (P = 0.056 and P = 0.121) at elevated than at ambient CO2 on the other two measuring days. Across the experiment, leaf RL was 65–71% of leaf RD at ambient and 76–83% at elevated CO2. Therefore, the inhibition by light on daytime leaf dark respiration was 29–35% for ambient and 17–24% for elevated CO2-grown plants.

Figure 3.

The ratio of leaf RL to leaf RD of X. strumarium grown at ambient (open symbols) or elevated (closed symbols) CO2 for five different sampling dates. The ratio of RL/RD ranged from 65–71% for ambient and 76–83% for elevated CO2-grown plants. P values for CO2 treatment on December 31, 1999 and January 5, 2000 were 0.056 and 0.121, respectively. Mean ± 1 SE; n = 18 for December 24, 1999, and n = 24 for the other measuring dates. **, P < 0.01.

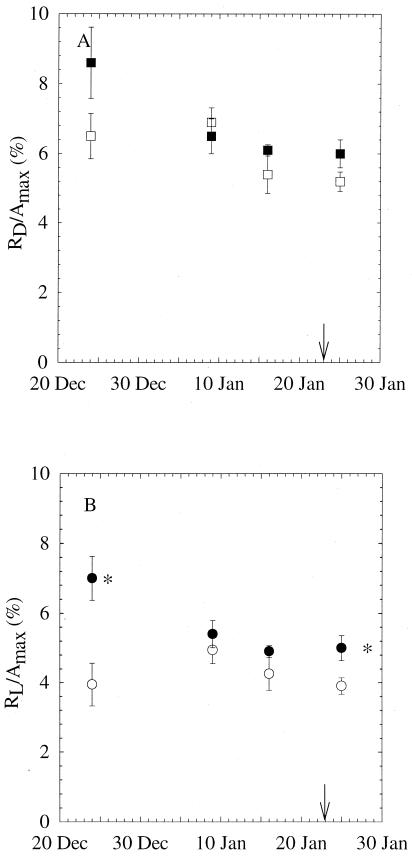

Leaf RD and RL were 5.2–8.6% and 3.9–7.0% of net maximum photosynthesis, respectively. There was no significant CO2 effect on RD/Amax on any measuring dates (Fig. 4A). The ratio of RL/Amax was significantly higher at elevated CO2 early in the experiment and after plants started flowering, but there was no significant difference between CO2 treatments in the middle of the growing period (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Percentages of leaf RD (A) and leaf RL (B) to maximum net photosynthetic rate (Amax) of X. strumarium grown at ambient (365 μmol mol−1, open symbols) or elevated (730 μmol mol−1, closed symbols) CO2 for four different sampling days. Arrow indicates starting date of flowering. n = 8–20; *, P < 0.05.

Nighttime Leaf Respiration.

Carbon dioxide concentration had no consistent effect on leaf RN, which was measured at the end of the daily dark period on 3 days during the experiment. Although leaf RN was 32% higher at elevated than at ambient CO2 before flowering initiation, it was 29% lower when flowers were in full bloom (P < 0.05, Table 1 Upper). No difference in leaf RN was observed between plants grown at different CO2 levels in the middle of the growing period. For ambient CO2-grown plants, percentage of leaf RN to leaf RD increased from 66 to 94% from the beginning to the end of the experiment. For elevated CO2-grown plants, the percentage decreased from 74 to 52% for the same period, because leaf RN at ambient CO2 remained little changed, whereas leaf RN at elevated CO2 showed a 55% decrease during that period. As observed in daytime leaf RD or RL, we found no significant effect of planting date on leaf RN (Table 1 Lower).

Table 1.

Effects of CO2 concentration and planting date on leaf dark respiration at night (RN; μmol m−2·s−1) of X. strumarium

| Dec 31

99

|

Jan 9 00

|

Jan 31 00

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 365 ppm | 730 ppm | 365 ppm | 730 ppm | 365 ppm | 730 ppm | |

| Effect of CO2 | ||||||

| 1.68 ± 0.32b | 2.21 ± 0.47a | 1.99 ± 0.47 | 1.66 ± 0.51 | 1.40 ± 0.32a | 1.00 ± 0.39b | |

| Effect of planting date | ||||||

| 0 | 1.65 ± 0.35 | 2.14 ± 0.20 | 1.92 ± 0.56 | 1.89 ± 0.39 | 1.58 ± 0.24 | 0.69 ± 0.28 |

| 5 | 1.59 ± 0.10 | 1.74 ± 0.49 | 1.93 ± 0.21 | 1.35 ± 0.22 | 1.43 ± 0.18 | 1.23 ± 0.24 |

| 10 | 1.68 ± 0.16 | 2.19 ± 0.36 | 1.59 ± 0.33 | 1.72 ± 0.22 | 1.23 ± 0.30 | 0.85 ± 0.20 |

| 15 | 1.81 ± 0.16 | 2.78 ± 0.53 | 2.10 ± 0.60 | 2.13 ± 0.39 | 1.42 ± 0.18 | 1.08 ± 0.23 |

| 20 | 1.93 ± 0.47 | 1.62 ± 0.53 | 1.36 ± 0.33 | 0.80 ± 0.26 | ||

| 25 | 2.49 ± 0.25 | 1.26 ± 0.37 | 1.36 ± 0.22 | 1.36 ± 0.29 | ||

Leaf temperature during respiration measurements was 20.0 ± 0.05°C. Different letters (

and

) indicate statistical significance at P ≤ 0.05 within the same day. n = 24 for CO2 treatments and n = 4–6 for planting dates. Mean ± 1 SE.

Leaf Respiration and Leaf Chemistry.

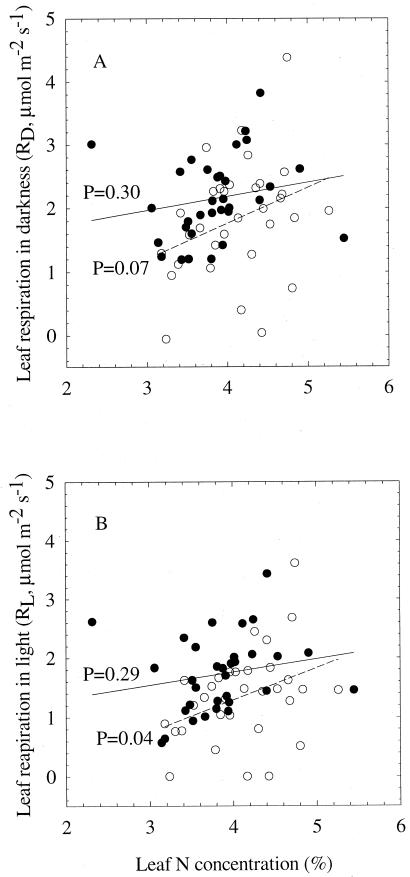

At ambient CO2, there was a significant positive correlation between leaf RL and leaf N (P = 0.04), but only a marginally significant correlation between leaf RD and leaf N (P = 0.07) (Fig. 5). The proportion of variation that can be attributed to the relationship between leaf RL and leaf N, however, is small (R2 = 0.136). At elevated CO2 there was no correlation between leaf RD or RL and leaf N. Neither leaf RL nor RD was significantly correlated with leaf starch concentration (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Relationship between leaf RD and leaf N concentration (A) and between leaf RL and leaf N concentration (B) of X. strumarium grown at ambient (open symbols, dashed lines) or elevated (closed symbols, solid lines) CO2. Also shown are the P values for the regressions between leaf respiration and leaf N concentration.

Discussion

Our results showed that leaf RL was significantly higher in elevated CO2 compared with ambient CO2-grown X. strumarium plants, suggesting higher energy output in light in elevated CO2-grown plants. There is abundant evidence showing that growth at elevated CO2 will greatly increase biomass production (16, 17). Higher biomass production will likely require more energy and carbon skeleton output from chloroplasts and mitochondria. This higher requirement can be met by more efficient cell metabolism and/or a larger number of energy- and reductant-producing organelles, mainly mitochondria. Although there has been no cellular level study examining whether cells can metabolize more efficiently at a higher CO2 concentration, studies have shown that the number of mitochondria increased dramatically at elevated CO2 in 10 species representing 8 families (21, 22). These plants were grown in environments that included growth and open-top chambers and Free-Air-CO2 Enrichment Facilities. Griffin et al. (22) also found a significant increase in the proportion of stroma thylakoid membranes to grana thylakoid membranes in leaves of the nine species studied. They hypothesized that plants adjusted cell ultrastructure for more ATP output from chloroplasts to meet the higher energy demand at elevated CO2 during daytime. Our results support their hypothesis by showing a significantly higher leaf mitochondrial respiration during illumination at elevated CO2. Their energy balance hypothesis is also supported by our findings showing that leaf RN had no consistent response to CO2 treatment during the experiment. It is possible that plants had different requirements for energy and carbon precursors and hence respiration at night.

Although to a different degree, daytime leaf R was significantly inhibited by light at both ambient and elevated CO2 in X. strumarium. The magnitude of inhibition found in our study by using the Kok method, 29–35% for ambient and 17–24% for elevated CO2-grown plants, was similar to the results found in seven Poa species by using the Laisk method (12). Villar et al. (6), however, found a much greater light inhibition of leaf R of 51 and 62% in two Californian chaparral shrubs also by using the Laisk method. The observed daytime inhibition of leaf respiration by light has been attributed to the accumulation of photosynthetic metabolites during illumination, such as ATP and NADPH, acting on respiratory enzymes as respiratory regulators (2, 23). Significantly higher daytime leaf RL and mitochondria numbers at elevated CO2 (21, 22), however, suggested that potential demand for ATP and reductants might be more important in determining the magnitude of light inhibition of leaf R.

It has been suggested that decreases in leaf R may be related to reduced leaf N content at elevated CO2 (24). However, leaf N status did not explain the effect of CO2 enrichment on leaf R in our study. Although leaf N was significantly lower at elevated CO2, leaf R was significantly higher at elevated CO2. It appears that higher leaf R in X. strumarium under CO2 enrichment was because of increased photosynthate production, as suggested by Brooks and Farquhar (5), rather than reduced protein turnover (24).

Leaf R during the day is typically estimated as the CO2 efflux from a leaf by either covering a clear cuvette with an opaque cloth (25) or turning off the light source and making the PAR zero (11). Leaf R measured in this manner is consequently used to assess the effects of elevated CO2 on carbon loss on leaf, plant, and ecosystem levels (9). This is a valid approach if light affects leaf R of ambient and elevated CO2-grown plants to the same extent. Our study, however, showed that this is not the case with X. strumarium. We found that the ratio of RL/RD at elevated CO2 (76–83%) is significantly higher than at ambient CO2 (65–71%), indicating less light inhibition of leaf R at elevated CO2. When leaf RD is used as an approximate measure of leaf RL, which is a more accurate estimate of nonphotorespiratory carbon loss during the day, we are underestimating daytime carbon loss at elevated CO2 by 11–12%. If light inhibits leaf R of ambient and elevated CO2-grown plants of other species in a similar manner, this finding will have important implications for how daytime carbon loss should be incorporated into the construction of the global carbon budget.

In summary, we found that leaf RD and RL in X. strumarium were significantly greater at elevated CO2 compared with ambient CO2, but that they were not related to leaf N content. Light inhibited leaf R at both ambient and elevated CO2, but the inhibition was greater for ambient than for elevated CO2-grown plants, presumably because elevated CO2-grown plants had a higher demand for energy and carbon skeletons. We demonstrated that using leaf R determined by shading leaves during the day as a measurement for respiratory carbon loss underestimates daytime leaf R of elevated CO2-grown plants by 10–11%. If this differential effect of light on leaf R of ambient and elevated CO2 exists in other species, the underestimate of carbon flux from ecosystems to the atmosphere at higher CO2 should be taken into consideration in models of the global carbon budget.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Bert Drake and George Koch for their constructive comments on an early version of the manuscript. We acknowledge with gratitude helpful input from discussions with Dr. Roger Anderson, Dr. Kim Brown, and Jennifer Nagel. Ardis Thompson provided skillful technical assistance in the execution of this study. This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation Grant IBN 9603940 to (K.L.G.) and by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Columbia Earth Institute to (X.Z.W.). This is Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory contribution number 6145.

Abbreviations

- Amax

net photosynthesis at saturated light

- PAR

photosynthetically active radiation

- R

dark respiration

- RD

daytime R measured by shading leaves

- RL

daytime R in light

- RN

nighttime R

References

- 1.Kromer S. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1995;46:45–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham D. In: The Biochemistry of Plants. A Comprehensive Treatise. Davies D D, editor. Vol. 2. New York: Academic; 1980. pp. 525–579. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foyer C H, Noctor G. New Phytol. 2000;146:359–388. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharp R E, Matthews M A, Boyer J S. Plant Physiol. 1984;75:95–101. doi: 10.1104/pp.75.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks A, Farquhar G D. Planta. 1985;165:397–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00392238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villar R, Held A A, Merino J. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:167–172. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.1.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poorter H, Gifford R M, Kriedemann P E, Wong S C. Aust J Bot. 1992;40:501–513. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wullschleger S D, Ziska L H, Bunce J A. Physiol Plant. 1994;90:221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drake B G, Azcon-Bieto J, Berry J, Bunce J, Dijkstra P, Farrar J, Gifford R M, Gonzalez-Meler M A, Koch G, Lambers H, et al. Plant Cell Environ. 1999;22:649–657. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas R B, Reid C D, Ybema R, Strain B R. Plant Cell Environ. 1993;16:539–546. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis P S, Vogel C S, Wang X Z, Pregitzer K S, Zak D R, Lussenhop J, Kubiske M E, Terri J A. Ecol Appl. 2000;10:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkin O K, Westbeek M H M, Cambridge M L, Lambers H, Pons T L. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:961–965. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.3.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkin O K, Evans J R, Ball M C, Lambers H, Pons T L. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:915–923. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.3.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zelitch I. Photosynthesis, Photorespiration and Plant Productivity. New York: Academic; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amthor J S. Global Change Biol. 1995;1:243–274. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cure J D. In: Direct Effects of Increasing Carbon Dioxide on Vegetation. Strain B R, Cure J D, editors. Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Energy; 1985. , DOE/ER Publ. No. (DOE) 0238, pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis P S, Wang X Z. Oecologia. 1998;113:299–313. doi: 10.1007/s004420050381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salisbury F B, Ross CW. Plant Physiology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kok B. Enzymology. 1948;13:1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laisk A K. Kinetics of Photosynthesis and Photorespiration in C3-Plants. Moscow: Nauka; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robertson E J, Williams M, Harwood J L, Lindsay J G, Leech R M. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:469–474. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.2.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffin K L, Anderson O R, Gastrich M D, Lewis J D, Lin G, Schuster W, Tissue D T, Turnbull M H, Whitehead D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2473–2478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041620898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCashing B G, Cossins E A, Canvin D T. Plant Physiol. 1988;87:155–161. doi: 10.1104/pp.87.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan M G. Ecol Appl. 1991;1:157–167. doi: 10.2307/1941808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wullschleger S D, Norby R J, Gunderson C A. New Phytol. 1992;121:515–523. [Google Scholar]