Abstract

17β-estradiol is a hormone with far-reaching organizational, activational and protective actions in both male and female brains. The organizational effects of early estrogen exposure are essential for long-lasting behavioral and cognitive functions. Estradiol mediates many of its effects through the intracellular receptors, estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα) and estrogen receptor-beta (ERβ). In the rodent cerebral cortex, estrogen receptor expression is high early in postnatal life and declines dramatically as the animal approaches puberty. This decline is accompanied by decreased expression of ERα mRNA. This change in expression is the same in both males and females in the developing isocortex and hippocampus. An understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) gene expression is critical for understanding the developmental, as well as changes in postpubertal expression of the estrogen receptor. One mechanism of suppressing gene expression is by the epigenetic modification of the promoter regions by DNA methylation that results in gene silencing. The decrease in ERα mRNA expression during development is accompanied by an increase in promoter methylation. Another example of regulation of ERα gene expression in the adult cortex is the changes that occur following neuronal injury. Many animal studies have demonstrated that the endogenous estrogen, 17β-estradiol, is neuroprotective. Specifically, low levels of estradiol protect the cortex from neuronal death following middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). In females, this protection is mediated through an ERα-dependent mechanism. ERα expression is rapidly increased following MCAO in females, but not in males. This increase is accompanied by a decrease in methylation of the promoter suggesting a return to the developmental program of gene expression within neurons. Taken together, during development and in adulthood, regulation of ERα gene expression in the cortex can occur by DNA methylation and in a sex-dependent fashion in the adult brain.

Introduction

Estrogens have long been known to play a crucial role in coordinating many neuroendocrine events that control sexual development, sexual behaviour and reproduction. 17β-estradiol is the primary biologically active form of estrogen. In rodents, estradiol is critical for sexual differentiation of the brain (see review by (McCarthy, 2008)). For example, estradiol organizes neural circuits and regulates apoptosis of neurons leading to long-term differences in the male and female brain (Anderson et al., 1986; Rhees et al., 1990; Toran-Allerand, 1976). In addition to its role in development, estradiol modulates numerous facets of brain function in the adult brain (for review see (McEwen and Alves, 1999) and (Simpkins and Singh, 2008)). Estradiol prevents neuronal cell death in a variety of brain injury models, modulates learning and memory and promotes the formation of synapses (Li et al., 2004; Sherwin, 1994; Simpkins et al., 1994; Wise et al., 2001; Woolley and McEwen, 1993).

The physiological effects resulting from estradiol actions in target tissues are mediated primarily by two intracellular receptors, ERα and ERβ (Green et al., 1986; Koike et al., 1987; Kuiper et al., 1996; Mosselman et al., 1996; White et al., 1987). Both ERα and ERβ have been observed in neurons and glia in the brain (Chaban et al., 2004; Donahue et al., 2000), and both are expressed throughout the brain with distinct patterns in different brain regions and with differing levels of expression during development (Gonzalez et al., 2007; Osterlund et al., 2000a; Osterlund et al., 2000b; Prewitt, 2007; Shughrue et al., 1997).

The ERα gene is highly conserved between human and rodents, containing similar gene and protein structures. ERα is preceded by multiple promoters that generate several mRNA splice variants (Hirata et al., 2001; Kos et al., 2001; Monje et al., 2007). Alternative splicing occurs at the first exon, which is then spliced to a common splice acceptor site upstream of the translational initiation codon in Exon 1. This alternative promoter splicing results in mRNA splice variants that differ only in their 5’ untranslated region encoding the same protein. These different mRNAs may be important in regulating stability or processing of the mRNA (Kos et al., 2001). Differences in the 5’UTRs may also provide for areas of different epigenetic modifications that can then modulate changes in gene expression. The regulatory binding sites of transcription factors that control gene expression are also likely located in the regions surrounding these promoters. To date, relatively little is known about the molecular composition of the regulatory elements that control ERα gene expression.

The regulation of gene expression by epigenetic modification is an emerging mechanism for controlling neuronal gene expression. Epigenetic modification of chromatin involves changes to DNA bases and the associated proteins (for review see (Wolffe and Matzke, 1999) and (Klose and Bird, 2006)) in the absence of changes in the DNA sequence. Epigenetic modifications include histone acetylation, histone methylation and DNA methylation (Bird and Wolffe, 1999; Cooper and Krawczak, 1989). The first step in DNA methylation results in the enzymatic transfer of a methyl group to the 5’-position of the pyrimidine ring of a cytosine residue followed by a guanine (CpG dinucleotides). The modification of the cytosines in CpG residues are carried out initially by the enzyme DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) and maintained by DNMT1 (Klose and Bird, 2006). CpG residues are often found upstream or downstream of the transcriptional start site.

The methylated CpGs are stabilized by methyl-CpG-binding proteins. The family of methyl-CpG-binding proteins contains several members including methyl binding domain (MBD) proteins 1, 2, 3, 4 and MeCP2 (Nan et al., 1998; Ng et al., 2000; Ng et al., 1999). These proteins bind to the methylated CpG residues potentially disrupting transcription. These proteins can also associate with co-repressor protein complexes of promoters that include histone deacetylases (HDAC) (Ballestar and Wolffe, 2001; Wade, 2001). Together, these complexes suppress transcription of genes with methylated promoter DNA.

Epigenetic modification of chromatin in neurons has been shown to play an important role in regulating gene expression during neuronal development and in learning and memory (Kiefer, 2007; Levenson and Sweatt, 2005). MeCP2 gene mutations are also the cause of some cases of Rett syndrome, a progressive neurological developmental disorder that appears during early childhood when sensory experience is driving the synaptic reorganization required for creating mature circuits in the brain (Zoghbi, 2003) (Guy et al., 2001). Furthermore, MeCP2 is present in high levels in mature neurons (Meehan et al., 1992), and studies suggest that the MeCP2 protein plays a role in forming synapses between neurons (Zhou et al., 2006). Additionally, MeCP2 is differentially expressed in the hypothalamus during a critical time in sexual differentiation of the brain (Kurian et al., 2008). Furthermore, DNMT3 expression has also been shown to be dynamically regulated in the developing brain as well as in the adult cortex (Feng et al., 2005; Siegmund et al., 2007).

The ERα gene undergoes changes in promoter methylation under normal and pathological conditions. For example, methylation of the ERα promoter has been reported to occur in the colon during aging (Issa et al., 1994) and changes in the expression of ERα have been associated with the progression of numerous types of cancerous tissues including breast and lung (Issa et al., 1994; Issa et al., 1996; Lapidus et al., 1998; O'Doherty et al., 2002; Oh et al., 2001; Ottaviano et al., 1994; Sasaki et al., 2002). Although evidence exists for multiple mechanisms of epigenetic modification of the ERα gene, DNA methylation has been the most widely described epigenetic phenomenon, and is the first epigenetic mechanism we have investigated.

Developmental regulation of estrogen receptor-alpha mRNA

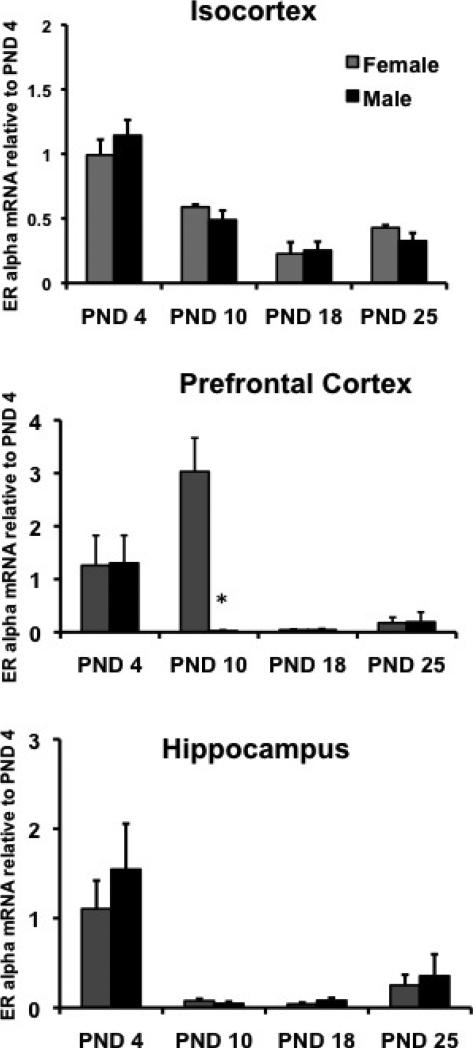

ERα protein and mRNA levels change dramatically during postnatal brain development (Shughrue et al., 1997; Simerly et al., 1990; Toran-Allerand et al., 1992). High levels of estradiol binding in non-hypothalamic regions such as the cortex and hippocampus during the first two weeks of life have been identified by receptor autoradiography (Pfaff and Keiner, 1973; Sheridan, 1979; Shughrue et al., 1990). This expression declines as animals approach puberty. In later studies in rats and mice, ERα mRNA expression was shown to correlate with the changes in estrogen binding in the hippocampus and cortex (O'Keefe et al., 1995; Prewitt, 2007). While estrogen receptors can be expressed in both neurons and glial cells, studies using in situ hybridization have demonstrated that the expression in the cortex is primarily in neurons. We examined ERα mRNA expression in the isocortex during postnatal development by quantitative real-time RT-PCR and determined that the decline in ERα mRNA expression begins during the second week of life (Prewitt, 2007) (Figure 1). We also examined ERα mRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex as this area may be responsible for cognitive processes potentially modified by estradiol. We saw a similar decline in ERα mRNA expression, however, with a significant sex difference on PND10. The result of this difference at this age is not known in rodents, but may play a role in sex differences and hormonal influences observed in cognitive behaviors associated with the prefrontal cortex (Galea et al., 2008; Overman, 2004; Welborn et al., 2009). Consistent with other studies, we have found that ERα mRNA in the whole hippocampus declines during development as well (Figure 1) replicating what others have shown (Shughrue et al., 1990 and O'Keefe, 1995 #179).

Figure 1. ERα mRNA expression during early postnatal development.

RNA was extracted from brain tissue taken from female and male mice at PND 4, 10, 18 and 25. RNA was reverse-transcribed and the resulting cDNA was used for real time PCR using ERα-specific primers. (A.) ERα mRNA expression was high in both the male and female isocortex at PND 4. ERα was significantly decreased in both male and female cortex at PND 10, 18 and 25 (Prewitt, 2007). (B). ERα mRNA expression was high in both the male and female PFC at PND 4. ERα was significantly increased in the female, but not male PFC at PND 10. ERα was significantly decreased in both male and female PFC at PND 18 and 25. (C). ERα mRNA expression was high in both the male and female hippocampus at PND 4. ERα was significantly decreased in both male and female hippocampus at PND 10, 18 and 25. Data was normalized to Histone 3.1 and compared to PND 4. Samples were run in triplicate. In all three brain regions, two-way ANOVA revealed a significant overall effect of age (p<0.01). Asterisks on the graph indicate significant differences from PND 4 (p< 0.05, n=6-8 per timepoint).

To determine the mechanisms by which this developmental regulation of ERα mRNA occurs, several experiments have been performed to test whether the signals are intrinsic to the neurons themselves. When either fetal rat hippocampal or cortical tissue was transplanted to the brain of a neonatal animal, the developmental profile of ERα mRNA expression in the transplants continued with the profile of the age of the donor (O'Keefe et al., 1993). This suggests that the control of ERα gene expression is programmed in the developing tissue and does not rely on cues from the surrounding tissue. Similar results were observed with transplants from the hypothalamus transplanted to animals treated with different hormonal paradigms (Paden et al., 1985), suggesting that hormonal signals do not regulate ERα expression at this age.

The molecular factors that control ERα mRNA expression at the transcriptional levels are not well known. One example, however, includes the transcription factor Stat5 (Champagne et al., 2006). Stat5 is associated with the JAK2-Stat5 signaling pathway and has shown to be activated by prolactin (Frasor et al., 2001). The rat promoter contains the consensus sequence for Stat5 (Frasor and Gibori, 2003). Following prolactin treatment, ERα mRNA expression is increased in the uterus and in the medial preoptic area of the hypothalamus. Furthermore, inhibition of Stat5 binding abolishes the ability of prolactin to increase ERα gene expression indicating its role in the hypothalamus (Champagne et al., 2006). While the possibility of this factor regulating ERα mRNA in the cortex exists, the expression of Stat1 and Stat5 actually increase during postnatal development (Claudio et al., 1998), suggesting it is likely that additional mechanisms of ERα mRNA regulation in the brain will be found.

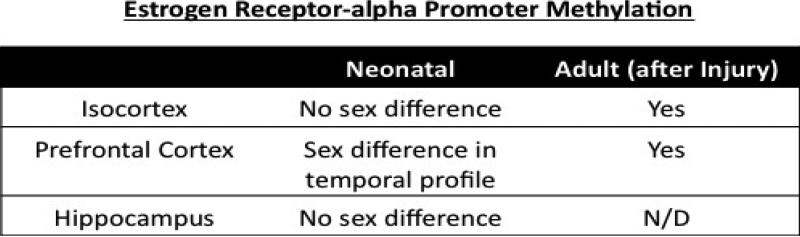

To investigate such additional potential mechanisms regulating this decline in ERα mRNA expression across early postnatal development, we examined the methylation status of the ERα promoter (Prewitt et al., 2007). Genomic DNA was isolated from cortical tissue and the methylation status of the ERα promoters was analyzed by methylation specific PCR (MSP) followed by pyrosequencing of the product (Westberry et al., 2010). This technique examines the methylation status of the cytosines in CpG regions of the promoter. Using this technique, we have observed that several of the promoters of the mouse ERα gene become progressively methylated beginning at postnatal day 10 (Westberry et al., 2010). This age corresponds with the beginning of the decline in ERα mRNA expression in the cortex. Furthermore, chromatin precipitation assays determined that the methyl-DNA binding protein, MeCP2, is associated with this promoter at the same time it becomes methylated. These observations suggest that methylation may play a role in the suppression of ERα mRNA in the developing brain and that the ERα promoter is a target of MeCP2 activity. Matching the mRNA expression, no sex difference was observed. Additionally we examined the expression pattern of the de novo DNMT, DNMT3A, in the isocortex, prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. A gradual increase with age was observed in DNMT3A mRNA expression and no sex difference was seen (Wilson, 2009). However, DNMT1 mRNA was significantly lower in the adult male prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. Suggesting potential sex differences in modulation of genes by methylation in the adult.

Regulation of estrogen receptor-alpha mRNA following stroke

In addition to the developmental changes in expression in ERα mRNA widely described, ERα mRNA expression is also dramatically regulated following brain injury. Middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) is a well-established model of focal ischemia. Studies in rats and mice have demonstrated a gender difference in neuronal cell death following MCAO. Female brains are consistently protected against cell death (Alkayed et al., 1998; Rusa et al., 1999; Simpkins et al., 1997). Pretreatment with low doses of estradiol prevents apoptosis in the overlying penumbral cortex of both female and male rats (Dubal et al., 1998; Rusa et al., 1999; Toung et al., 1998). In this model of brain injury the ability of estradiol to act as a neuroprotectant is dependent on the presence of ERα (Dubal et al., 2001; Rau et al., 2001). As discussed above, ERα mRNA expression is very low in the adult cortex, however, following unilateral MCAO, the ERα gene in the cortex is rapidly increased on the injured side of the brain (Dubal et al., 2006). This activation is independent of estradiol treatment, although some differences are observed in the timecourse of expression. Furthermore, this increase is critical for estradiol neuroprotection because in female ERα knockout mice, estradiol is no longer protective (Dubal et al., 1999). We have extended these studies and performed MCAO in males and females to examine the regulation of ERα gene expression. In this model of injury, males have a much larger MCAO-induced cell loss than females and estradiol is also neuroprotective (Alkayed et al., 1998; Toung et al., 1998). We determined that the increase in ERα mRNA expression only occurs in females, as males do not show a similar increase (Westberry et al., 2008a). Furthermore, estradiol treatment had no effect in females or males on the induction of ERα mRNA expression following MCAO. Interestingly, in gonadectomized males ERα mRNA expression is increased as in females suggesting a suppressive effect of androgens on the ability of the ERα gene to be activated following MCAO (Westberry et al., 2009). The fact that E2 can be protective in males but we failed to show a change in ERα mRNA expression, suggests that the mechanisms of neuroprotection by estradiol is different in males and females and remains to be determined. Additionally, alterations in the regulation of DNA methylation of the ERα promoter resulting in changes in mRNA expression could contribute to the observation that estradiol is not neuroprotective in reproductively senescent females (Selvamani and Sohrabji, 2008). Although ERα receptor levels were not examined in this study, overall DNA methylation levels increase in the aging brain (Richardson, 2003) and we have observed effects of age on the methylation of the ERβ promoter in the aging rat (Westberry et al., 2008b).

We have also examined methylation status of the ERα promoter in intact male and female rats following MCAO (Westberry et al., 2008a). Genomic DNA was isolated from micropunches from the cortex adjacent to the area of the injury or on the corresponding areas on the control side of the brain 24 hours after injury and individual CpG residues analyzed by pyrosequencing. We found that ischemia decreased methylation in the ischemic cortex of females, while there was no change in methylation in the male. Interestingly some CpGs are never methylated, some are always methylated, and others appear susceptible to changes after injury. More CpG islands are methylated on the control side of the brain as compared to the injured side. Furthermore, the overall level of methylation of the ERα gene is lower in the injured side of the brain.

The association of MeCP2 with the ERα promoter using chromatin immunoprecipitation assays was also examined in intact male and female rats after MCAO. MeCP2 was associated with the ERα promoter on the uninjured side of the brain of both male and female rats, but dissociated from the ERα promoter following injury only in female rats, corresponding with the methylation status of the promoter (Westberry et al., 2008a). Together these data demonstrate a difference in the regulation of ERα mRNA expression in response to MCAO between male and female rats and this difference is correlated with altered DNA methylation. Additionally, the male gonadal hormones may influence the changes in DNA methylation and gene expression following a neuronal injury.

Taken together these data suggest that following a brain injury such as stroke, the gene expression mechanisms within neurons are altered, particularly in females, and resemble those observed early in development, potentially as a compensatory mechanism to prevent cell death or as a potential recovery mechanism. Previously changes in expression in proteins responsible for neurodevelopment including growth-associated-protein-43 and microtubule-associated protein 1B have been shown to be regulated following a neuronal injury (Emery et al., 2003) leading to the hypothesis that neurons revert back to an early neurodevelopment pattern of gene expression when challenged with an injury. The data discussed here with the reversible epigenetic regulation of the ERα gene would lend further support to this hypothesis.

Summary

Estrogens mediate many diverse and critical actions in the brain. Most of these actions require the presence of classical estrogen receptors. Thus, coordinated regulation of the estrogen receptor genes is critical for mediating these responses to estrogens in an age, gender, and brain region-specific manner. Alterations in the normal regulation either during development, disease or aging could potentially interfere with estradiol action. We have begun to identify numerous physiological influences that can influence the expression of the estrogen receptor gene by reversible epigenetic mechanisms. Furthermore, some of these mechanisms are differentially regulated in the male and female brain, particularly in the adult. A deeper understanding of these mechanisms will ultimately lead to our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying differences in the male and female brain, and importantly, differences in how the male and female brain may be able to respond to neuronal insults encountered with injury, neurodegeneration and normal aging.

Figure 2. Summary of sex differences in ERα promoter methylation in the brain.

N/D not determined.

Acknowledgements

This work cited from our laboratory was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF IOS0919944), COBRE grant P20 RR15592 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), and R01 HL073693 (MEW). All opinions, findings and conclusions expressed in this material are those of the authors and not those necessarily of NSF or NCRR.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alkayed NJ, et al. Gender-linked brain injury in experimental stroke. Stroke. 1998;29:159–65. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.1.159. discussion 166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RH, et al. Relationships between sexual activity, plasma testosterone, and the volume of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area in prenatally stressed and non-stressed rats. Brain Res. 1986;370:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballestar E, Wolffe AP. Methyl-CpG-binding proteins. Targeting specific gene repression. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:1–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird AP, Wolffe AP. Methylation-induced repression--belts, braces, and chromatin. Cell. 1999;99:451–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaban VV, et al. A membrane estrogen receptor mediates intracellular calcium release in astrocytes. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3788–95. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA, et al. Maternal care associated with methylation of the estrogen receptor-alpha1b promoter and estrogen receptor-alpha expression in the medial preoptic area of female offspring. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2909–15. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudio D-F, et al. Members of the JAK/STAT proteins are expressed and regulated during development in the mammalian forebrain. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 1998;54:320–330. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981101)54:3<320::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DN, Krawczak M. Cytosine methylation and the fate of CpG dinucleotides in vertebrate genomes. Hum Genet. 1989;83:181–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00286715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue JE, et al. Cells containing immunoreactive estrogen receptor-alpha in the human basal forebrain. Brain Res. 2000;856:142–51. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, et al. Estradiol protects against ischemic injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1253–8. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, et al. Differential modulation of estrogen receptors (ERs) in ischemic brain injury: a role for ERalpha in estradiol-mediated protection against delayed cell death. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3076–84. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, et al. Estradiol modulates bcl-2 in cerebral ischemia: a potential role for estrogen receptors. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6385–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06385.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubal DB, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha, not beta, is a critical link in estradiol-mediated protection against brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1952–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041483198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery DL, et al. Plasticity following injury to the adult central nervous system: is recapitulation of a developmental state worth promoting? J Neurotrauma. 2003;20:1271–92. doi: 10.1089/089771503322686085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, et al. Dynamic expression of de novo DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b in the central nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:734–46. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasor J, et al. PRL-induced ERalpha gene expression is mediated by Janus kinase 2 (Jak2) while signal transducer and activator of transcription 5b (Stat5b) phosphorylation involves Jak2 and a second tyrosine kinase. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1941–52. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.11.0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasor J, Gibori G. Prolactin regulation of estrogen receptor expression. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14:118–23. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(03)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea LA, et al. Endocrine regulation of cognition and neuroplasticity: our pursuit to unveil the complex interaction between hormones, the brain, and behaviour. Can J Exp Psychol. 2008;62:247–60. doi: 10.1037/a0014501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez M, et al. Distribu tion patterns of estrogen receptor alpha and beta in the human cortex and hippocampus during development and adulthood. J Comp Neurol. 2007;503:790–802. doi: 10.1002/cne.21419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green S, et al. Human oestrogen receptor cDNA: sequence, expression and homology to v-erb-A. Nature. 1986;320:134–9. doi: 10.1038/320134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy J, et al. A mouse Mecp2-null mutation causes neurological symptoms that mimic Rett syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;27:322–6. doi: 10.1038/85899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata S, et al. The multiple untranslated first exons system of the human estrogen receptor beta (ER beta) gene. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;78:33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa JP, et al. Methylation of the oestrogen receptor CpG island links ageing and neoplasia in human colon. Nat Genet. 1994;7:536–40. doi: 10.1038/ng0894-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa JP, et al. The estrogen receptor CpG island is methylated in most hematopoietic neoplasms. Cancer Res. 1996;56:973–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer JC. Epigenetics in development. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:1144–56. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose RJ, Bird AP. Genomic DNA methylation: the mark and its mediators. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike S, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of rat estrogen receptor cDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2499–513. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.6.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kos M, et al. Minireview: genomic organization of the human ERalpha gene promoter region. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:2057–63. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.12.0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, et al. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5925–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurian JR, et al. Mecp2 Organizes Juvenile Social Behavior in a Sex-Specific Manner. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:7137–7142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1345-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidus RG, et al. Mapping of ER gene CpG island methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2515–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson JM, Sweatt JD. Epigenetic mechanisms in memory formation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:108–18. doi: 10.1038/nrn1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, et al. Estrogen alters hippocampal dendritic spine shape and enhances synaptic protein immunoreactivity and spatial memory in female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2185–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307313101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM. Estradiol and the developing brain. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:91–124. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Alves SE. Estrogen actions in the central nervous system. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:279–307. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan RR, et al. Characterization of MeCP2, a vertebrate DNA binding protein with affinity for methylated DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5085–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.19.5085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monje L, et al. Neonatal exposure to bisphenol A modifies the abundance of estrogen receptor {alpha} transcripts with alternative 5'-untranslated regions in the female rat preoptic area. J Endocrinol. 2007;194:201–12. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosselman S, et al. ER beta: identification and characterization of a novel human estrogen receptor. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan X, et al. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature. 1998;393:386–9. doi: 10.1038/30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng HH, et al. Active repression of methylated genes by the chromosomal protein MBD1. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1394–406. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1394-1406.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng HH, et al. MBD2 is a transcriptio nal repressor belonging to the MeCP1 histone deacetylase complex. Nat Genet. 1999;23:58–61. doi: 10.1038/12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Doherty AM, et al. Methylation status of oestrogen receptor-alpha gene promoter sequences in human ovarian epithelial cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:282–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe JA, et al. Estrogen receptor mRNA alterations in the developing rat hippocampus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;30:115–24. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00284-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe JA, et al. The ontogeny of estrogen receptors in heterochronic hippocampal and neocortical transplants demonstrates an intrinsic developmental program. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1993;75:105–12. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90069-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh AS, et al. Hyperactivation of MAPK induces loss of ERalpha expression in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1344–59. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.8.0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MK, et al. The human brain has distinct regional expression patterns of estrogen receptor alpha mRNA isoforms derived from alternative promoters. J Neurochem. 2000a;75:1390–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MK, et al. Estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) expression within the human forebrain: distinct distribution pattern to ERalpha mRNA. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000b;85:3840–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.10.6913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaviano YL, et al. Methylation of the estrogen receptor gene CpG island marks loss of estrogen receptor expression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2552–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overman WH. Sex differences in early childhood, adolescence, and adulthood on cognitive tasks that rely on orbital prefrontal cortex. Brain Cogn. 2004;55:134–47. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paden CM, et al. Estrogen and progestin receptors appear in transplanted fetal hypothalamus-preoptic area independently of the steroid environment. J Neurosci. 1985;5:2374–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-09-02374.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff D, Keiner M. Atlas of estradiol-concentrating cells in the central nervous system of the female rat. J Comp Neurol. 1973;151:121–58. doi: 10.1002/cne.901510204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prewitt AK, et al. Developmental regulation of estrogen receptor-alpha mRNA via promoter methylation in the mouse cortex. Endocrine Society. 2007 Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Prewitt AKW, M.E. Changes in estrogen receptor-alpha mRNA in the mouse cortex during development. Brain Res. 2007;1134:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau SW, et al. Estradiol protects against apoptotic cell death in stroke injury: possible mechanisms. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 2001;27:1165. [Google Scholar]

- Rhees RW, et al. Onset of the hormone-sensitive perinatal period for sexual differentiation of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area in female rats. J Neurobiol. 1990;21:781–6. doi: 10.1002/neu.480210511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson B. Impact of aging on DNA methylation. Ageing Res Rev. 2003;2:245–61. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(03)00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusa R, et al. 17beta-estradiol reduces stroke injury in estrogen-deficient female animals. Stroke. 1999;30:1665–70. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.8.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki M, et al. Methylation and inactivation of estrogen, progesterone, and androgen receptors in prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:384–90. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.5.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvamani A, Sohrabji F. Reproductive age modulates the impact of focal ischemia on the forebrain as well as the effects of estrogen treatment in female rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan PJ. Estrogen binding in the neonatal neocortex. Brain Res. 1979;178:201–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin BB. Estrogenic effects on memory in women. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;743:213–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb55794.x. discussion 230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue PJ, et al. Comparative dist ribution of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta mRNA in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:507–25. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971201)388:4<507::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue PJ, et al. Developmental changes in estrogen receptors in mouse cerebral cortex between birth and postweaning: studied by autoradiography with 11 beta-methoxy-16 alpha-[125I]iodoestradiol. Endocrinology. 1990;126:1112–24. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-2-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund KD, et al. DNA Methylation in the Human Cerebral Cortex Is Dynamically Regulated throughout the Life Span and Involves Differentiated Neurons. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly RB, et al. Distribution of androgen and estrogen receptor mRNA-containing cells in the rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol. 1990;294:76–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.902940107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins JW, et al. Estrogens may reduce mortality and ischemic damage caused by middle cerebral artery occlusion in the female rat. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:724–30. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.5.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins JW, Singh M. More than a decade of estrogen neuroprotection. Alzheimer's and Dementia. 2008;4:S131–S136. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpkins JW, et al. The potential role for estrogen replacement therapy in the treatment of the cognitive decline and neurodegeneration associated with Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1994;15(Suppl 2):S195–7. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)90205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand CD. Sex steroids and the development of the newborn mouse hypothalamus and preoptic area in vitro: implications for sexual differentiation. Brain Res. 1976;106:407–12. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)91038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand CD, et al. Cellular variations in estrogen receptor mRNA translation in the developing brain: evidence from combined [125I]estrogen autoradiography and non-isotopic in situ hybridization histochemistry. Brain Res. 1992;576:25–41. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90606-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toung TJ, et al. Estrogen-mediated neuroprotection after experimental stroke in male rats. Stroke. 1998;29:1666–70. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.8.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade PA. Methyl CpG-binding proteins and transcriptional repression. Bioessays. 2001;23:1131–7. doi: 10.1002/bies.10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welborn BL, et al. Variation in orbitofrontal cortex volume: relation to sex, emotion regulation and affect. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2009;4:328–39. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westberry JM, et al. Epigenetic Regulation of the Estrogen Receptor Alpha Promoter in the Cereberal Cortex Following Ischemia in Male and Female Rats. Neuroscience. 2008a;152:982–989. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westberry JM, et al. Mechanisms of regulation of estrogen receptor beta gene expression in the cortex of female rats during aging. Society for Neuroscience. 2008b Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Westberry JM, et al. Changes in promoter methylation in the rat cortex following midle cerebral artery occulsion. Society for Neuroscience. 2009 Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Westberry JM, et al. Epigenetic regulation of estrogen receptor alpha gene expression in the mouse cortex during early postnatal development. Endocrinology. 2010;151:731–40. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R, et al. Structural organization and expression of the mouse estrogen receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1987;1:735–44. doi: 10.1210/mend-1-10-735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson ME. Methylation of the ER promoter as a regulator of brain region specific hormone sensitivity. Society for Neuroscience, Chicago. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Wise PM, et al. Estrogens: trophic and protective factors in the adult brain. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2001;22:33–66. doi: 10.1006/frne.2000.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolffe AP, Matzke MA. Epigenetics: regulation through repression. Science. 1999;286:481–6. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Roles of estradiol and progesterone in regulation of hippocampal dendritic spine density during the estrous cycle in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336:293–306. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, et al. Brain-specific phosphorylation of MeCP2 regulates activity-dependent Bdnf transcription, dendritic growth, and spine maturation. Neuron. 2006;52:255–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoghbi HY. Postnatal neurodevelopmental disorders: meeting at the synapse? Science. 2003;302:826–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1089071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]