Abstract

This paper concerns the development of water-compatible fluorescent imaging-probes with tunable photonic properties that can be excited at a single wavelength. Bichromophoric cassettes 1a – 1c consisting of a BODIPY donor and a cyanine acceptor were prepared using a simple synthetic route, and their photophysical properties were investigated. Upon excitation of the BODIPY moiety at 488 nm the excitation energy is transferred through an acetylene bridge to the cyanine dye acceptor, which emits light at approximately 600, 700, and 800 nm, ie with remarkable dispersions. This effect is facilitated by efficient energy transfer that gives a ‘quasi-Stokes’ shift of between 86 – 290 nm opening a huge spectral window for imaging. The emissive properties of the cassettes depend on the energy transfer (ET) mechanism: the faster the transfer, the more efficient it is. Measurements of rates of energy transfer indicate that a through-bond energy transfer takes place in the cassettes 1a and 1b that is two orders of magnitude faster than the classical through-space, Förster, energy transfer (in the case of cassette 1c, however, both mechanisms are possible, and the rate measurements do not allow us to discern between them). Thus the cassettes 1a – 1c are well suited for multiplexing experiments in biotechnological methods that involve a single laser-excitation source. However, for widespread application of these probes their solubility in aqueous media must be improved. Consequently, the probes were encapsulated in calcium phosphate/silicate nanoparticles (diameter ca 22 nm) that are freely dispersible in water. This encapsulation process resulted in only minor changes in the photophysical properties of the cassettes. The system based on cassette 1a was chosen to probe how effectively these nanoparticles could be used to deliver the dyes into cells. Encapsulated cassette 1a permeated Clone 9 rat liver cells where it localized in the mitochondria and fluoresced through the acceptor part, ie red. Overall, this paper reports readily accessible, cyanine-based through-bond energy transfer cassettes that are lypophilic but can be encapsulated to form nanoparticles that disperse freely in water. These particles can be used to enter cells and to label organelles.

Introduction

Fluorescent labels that display high photo- and chemical stability, bright fluorescence and emission wavelength tunability are important tools in cellular biology.1,2 Such labels generally allow for high-quality images at lower photon flux, without sacrificing accuracy (low background). If the labels allow channel multiplexing then that is also an advantage as it facilitates tracking of several components in a single experiment.3,4 However, large Stokes’ shifts are required to achieve resolutions necessary for multiplexing experiments. These shifts correspond to energies required for reorganization from ground to excited states;5,6 for most planar, conjugated organic labels, compounds with relatively small Stokes’ shifts (10–20 nm),7 this parameter is not easily manipulated.8,9 Thus multiplexed fluorescent labels for excitation at one wavelength must involve compromise between two opposing physical parameters.3 If the excitation source is set at the absorption maxima of the dyes used, then all the dyes must have nearly the same absorption maxima and the limit of the resolution is defined by the Stokes’ shifts of the dyes. Conversely, if the dyes are chosen for their diverse fluorescence emission maxima, then the UV absorption maxima of some of the dyes will not correspond to the excitation wavelength, these dyes will absorb less light, and they will fluoresce less brightly.

Many applications in bioimaging require probes that are compatible with aqueous media. Incorporation of water-solubilizing groups in labels is a challenge10 and presents problems during purification5 especially since even small amounts of fluorescent impurities may skew the data obtained in imaging experiments. Furthermore, water-solubilizing groups attached to fluors often result in decreased fluorescence intensities due to non-radiative decay processes facilitated by solvation sphere rearrangement in the excited state. 11,12 Finally, if these obstacles are overcome, the resulting labels may be highly polar; this tends to impart an increased affinity for cytoplasm making the probes less useful for imaging of other cellular compartments.

Here we present a rational design of fluorescent labels that allows tuning of fluorescent outputs through a wide emission window via cassettes composed of donor and acceptor chromophores.8,11,13,14 Specifically, this paper describes cassettes that work via excitation of a BODIPY-based15–18 donor with blue light (eg 488 nm) followed by fast energy transfer to variable cyanine-based15,19,20 acceptors, which then emits red light. Three cassettes were prepared, 1a – 1c (Scheme 1). The wavelength of the emitted light depends on the structure of the acceptor, and varies from 590 to 794 nm. While the Stokes’ shift of the donor is short (~ 20 nm), the red shift in the cassettes is between 86 – 290 nm; this dispersion is greater than any other achieved in cassettes generated in these laboratories.21–29 These probes are relatively easy to make, partly because they are lipophilic, but they have poor water-solubilities. To obviate this issue, the cassettes were encapsulated in calcium phosphate/silicate nanoparticles that are freely dispersed in water. Experiments are described to elucidate how these particles can be used as delivery agents wherein the dye-containing particles become localized within the cells.

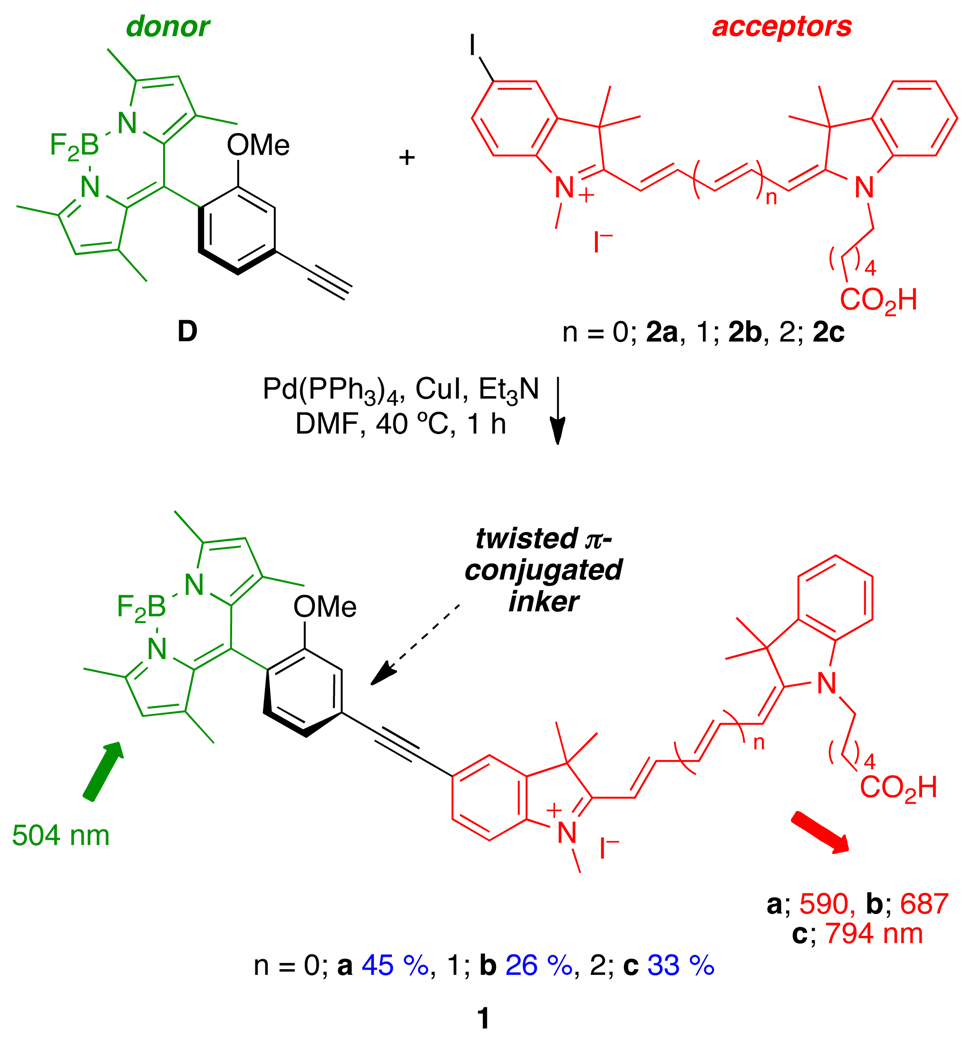

Scheme 1.

Syntheses of the TBET-cassettes 1a, 1b, 1c.

Results and Discussion

Syntheses and Spectroscopic Properties of the Cassettes

Cassettes 1a – 1c were prepared by cross-coupling the readily available donor fragment D with the iodine-functionalized cyanine dyes 2a – 2c (Scheme 1, and SI). These materials were easily purified via flash chromatography because they are lipophilic and colored.

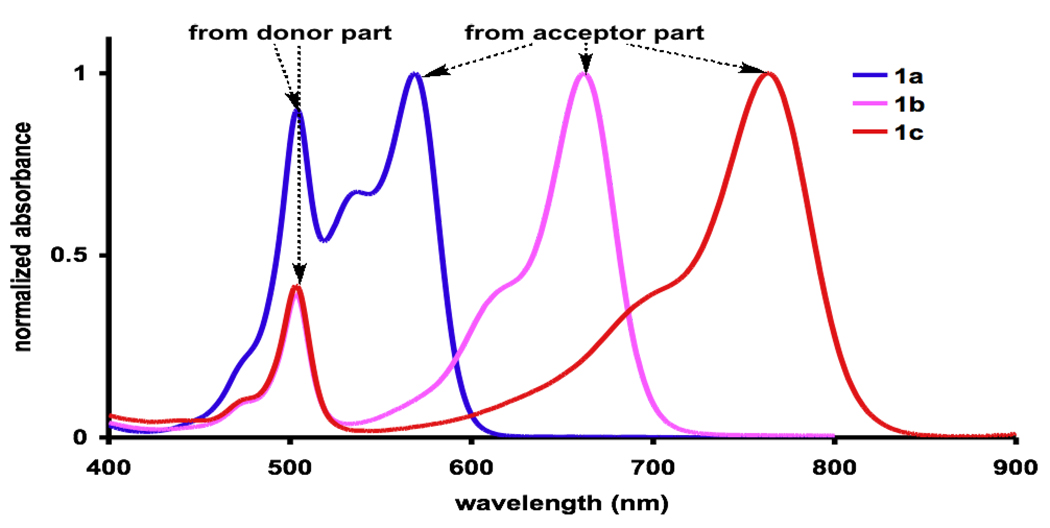

Spectroscopic data for the cassettes 1 are presented in Figure 1 and Table 1. Figure 1a shows the absorbance spectra; these resemble the summation of components from the donor and acceptor fragments. When the cassettes are excited at 504 nm (the donor), 1a and 1b emit predominantly from their acceptor fragments; only about 10 % of the fluorescence “leaks” from the donor part. Leakage from the donor is prevalent in the fluorescent spectra of 1c under the same conditions. Quantitatively, this parameter is reflected by the “energy transfer efficiencies” (ETEs; {Φd/Φa} × 100)29 of these cassettes (1a and 1b >88 %; 1c, 43 %).

Figure 1.

Normalized a absorbance and b fluorescence spectra of the cassettes in EtOH (at 10−6 and 10−7 M for absorbance and fluorescence measurements, respectively).

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of cassettes

| λ abs | λ emiss | Φda | Φab | ETE (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in EtOH | |||||

| 1a | 504, 569 | 519, 590 | 0.20+/−0.01 | 0.22+/−0.02 | 90 |

| 1b | 504, 662 | 519, 687 | 0.35+/−0.02 | 0.40+/−0.03 | 87 |

| 1c | 504, 763 | 519, 794 | 0.11 | -c | 43d |

| nanoparticles in pH 7.4 phosphate buffer | |||||

| 1a | 504, 568 | 519, 592 | 0.26+/−0.01 | 0.29+/−0.02 | 88 |

| 1b | 504, 659 | 519, 687 | 0.063 | 0.071 | 89 |

| 1c | 504, 764 | 519, 793 | 0.053 | -c | 41d |

Φd : Φ of acceptor when excited at donor relative to rhodamine 6G (Φ 0.92 in EtOH);

Φa : Φ of acceptor when excited at acceptor relative to rhodamine 101 for 1a (Φ 1.0 in EtOH), and Nile Blue for 1b (Φ 0.27 in EtOH). Quantum yields were measured three times and averaged, and were corroborated using the absolute fluorescence quantum yield measurements. ETE: energy transfer efficiency (Φd/Φa) × 100.

No appropriate standard due to range of wavelengths.

See SI for calculation.

We speculate that the difference in quantum yield for the three cassettes after encapsulation is due to the orientation of the cassettes within the particles. In case of cassette 1a (Cy3 cassette) the fluor is well encapsulated and devoid of any π-stacking, hence its quantum yield is high. However 1b and 1c may be oriented in ways that favor more π-stacking, resulting in lower quantum yields.

Ultra-fast Spectroscopy Measurements

Ethynylene linkers were incorporated in cassettes 1a – 1c to facilitate donor-to-acceptor energy transfer through-bonds,30 though through-space energy transfer is also plausible. Femtosecond transient spectroscopy was performed to compare actual rates of energy transfer in these systems to ones calculated for transfer through-space (FRET). As a control, intermolecular energy transfer between the donor D in ethanol with equimolar (3.1 × 106 M) concentration of non-iodinated analog of the acceptors (2a, Cy3) was also studied. Energy transfer did occur under these conditions, at a rate of 1.85 × 109 s−1.

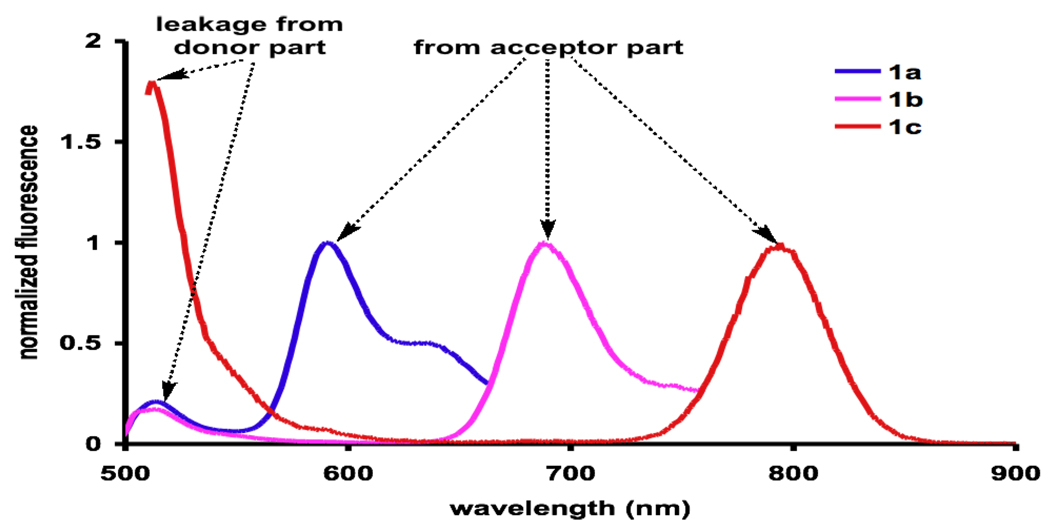

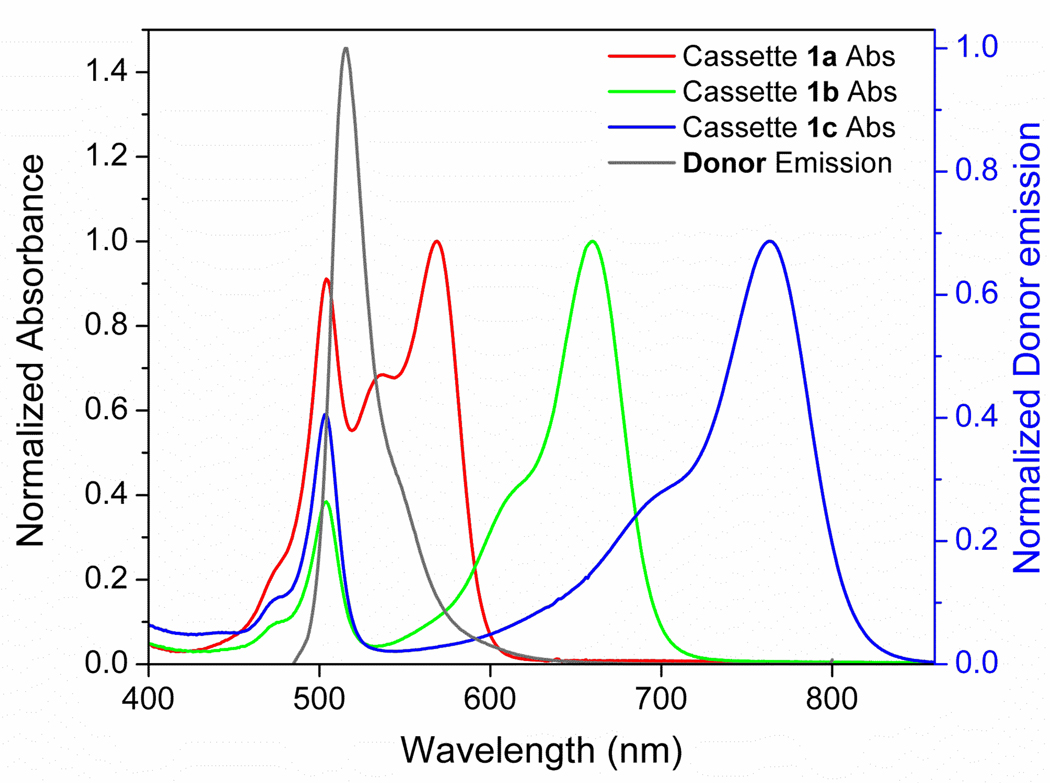

Energy transfer rates were measured for the cassettes 1a – 1c (at the concentration of 3.1×10−6 M) and compared with the rates calculated for through-space energy transfer using the Förster model (Table 2). From the perspective of the resonance energy transfer (RET) theory, the overlap integral J for the emission of the donor (common for the three cassettes) and the absorption of the indocyanine acceptor (Figure 2) show a step-wise decrease 1a > 1b > 1c while the Förster radius (R0) increases. Following the Förster model, the calculated theoretical value for the resonance energy transfer decreases from 8.59 × 109 for 1a to 1.88 × 109 (1b), and 1.39 × 109 (1c), respectively (Table 2). Consequently, the Förster energy transfer rate calculated for cassette 1a, for instance, was approximately four times faster than the observed rate for the intermolecular transfer in the control described above.

Table 2.

Energy transfer data calculated and recorded using time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy and femtosecond transient spectroscopy in ethanol at 22 °C.

| Cassette | Transfer rate measured (s−1) |

Förster radius calcd. R0 (Å) |

Overlap int. J (M−1 cm3 nm4) |

Transfer rate calcd. (s−1) a |

Measured ET efficiency (%) |

Donor decay (ps) |

Acceptor raise (ps) |

Acceptor decay (ps) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 4.85 × 1011 | 129 | 3.47 × 1017 | 8.59 × 109 | 90 | 2.06 | 2.18 | 352 |

| 1b | 1.26 × 1011 | 100 | 7.61 × 1016 | 1.88 × 109 | 87 | 7.96 | 9.55 | ~1000 |

| 1c | 1.26 × 109 | 94 | 5.14 × 1016 | 1.39 × 109 | 43 | 794 | ND b | 719 |

Transfer rate for the Förster through-space ET was calculated using r (donor-acceptor distance) determined as an average center-to-center distance using kT (r) = R06/τD , χ2=2/3. r6 formula and r = 66.41 Å.

Relatively fast population of the acceptor singlet excited state occurred due to the direct pumping of the acceptor absorption by the laser (1c: ε420 = 9800 M−1cm−1).

Figure 2.

Spectral overlap of BODIPY donor emission ( ) and cassette absorption (1a

) and cassette absorption (1a  ; 1b

; 1b  ; 1c

; 1c  ) ensures resonance energy transfer (RET).

) ensures resonance energy transfer (RET).

Observed energy transfer rates for cassettes 1a – 1b were two orders of a magnitude higher than the rates predicted for the Förster model. Specifically, the rates for 1a and 1b are 56 and 67 times faster than the ones calculated for through-space energy transfer (Table 2). These data suggest a dramatic effect of the donor-acceptor communication through the phenylethyne bridge.

Cassette 1c shows an energy transfer rate equal (within 10% error) to the through-space energy transfer rate following the Förster model. This suggests that in 1c the resonance energy transfer proceeds through-space or in a mixed through-space and through-bond mechanism. Overall, the measured rates suggest the efficiency decreases from 90 to 87 and 43% for 1a, 1b and 1c, respectively.

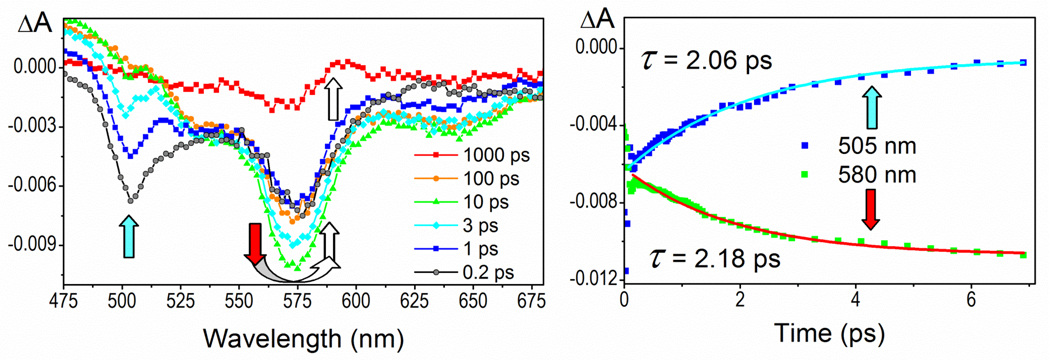

On a picosecond-timescale, energy transfer was observed by following the concerted kinetics of the donor stimulated emission decay following the excitation and the population of the acceptor excited state following the bleaching of the donor. After the energy is transferred, the acceptor decays at its usual timescale, ie as if excited directly. For example, excitation of cassette 1a at the donor (420 nm) by a femtosecond laser pulse is followed by the decay of a singlet state, which is complete within 2.1 ps and is accompanied by the population of an acceptor excited state with 2.2 ps raise time. Thereafter, the acceptor decays with a fluorescence lifetime of 352 ps by emitting with a λmax of 600 nm (Figure 3). Similarly, exciting cassette 1b at 420 nm results in singlet state population of the BODIPY donor, decay within 8.0 ps, then complete population of the acceptor excited state after 9.6 ps; the acceptor singlet excited state decays with a fluorescence lifetime of 840 ps (λmax = 680 nm). In contrast to the other two cassettes, the donor of 1c decays slowly (within 800 ps) which suggests that the excited state of the donor is not being depopulated by a strongly coupled acceptor as it is in the cassettes 1a and 1b, and the energy transfer is less efficient. Through-space RET is still operational in the cassette 1c since the donor alone decays with a lifetime of 4 ns which is comparable to the 800 ps rate in the cassette.

Figure 3.

Left: Transient absorption spectra of the cassette 1a showing a concerted depletion of the stimulated emission donor maximum at 505 nm (blue arrow) and raise of the acceptor maxima at 580 nm (red arrow) followed by acceptor relaxation within 350 ps. Right: Kinetic profiles of the donor decay (2.06 ps) and acceptor raise (2.18 ps) reflect the concerted process.

The following conclusions can be drawn from the measurement of energy transfer rates. First, a significantly more efficient pathway for donor-acceptor communication exists for cassettes 1a and 1b than compared to that in 1c. Aryl-ethynyl-aryl moieties display a strong electronic coupling30 and this suggests that the energy transfer takes place through the bridge. The efficiency and rate of the energy transfer processes in 1a and 1b are a strong indication of an exciton hopping mechanism.31–34 Cassette 1c transfers energy at a rate that can be rationalized using the Förster through-space model.

Encapsulation of the Dyes In Calcium Phosphate/silicate

Cassettes 1a – 1c are not water-soluble, but we show here they can be encapsulated in calcium phosphate to form nanoparticles. With respect to biotechnological applications, calcium phosphate is an excellent matrix for nanoparticle encapsulation because: (i) moderate concentrations of Ca2+ ions are not toxic to cells; (ii) it is not toxic in vivo (found in human bone, and teeth); (iii) it is claimed that calcium phosphate dissolves below pH 5.5 to liberate the cargo, but is stable at 7.4;35 (iv) particles of this matrix disperse freely in aqueous media; and, (v) the surface of these particles can be functionalized.36,37 Adair and co-workers have shown that spherical, ca 18 nm diameter, calcium phosphate nanoparticles can be formed with citrate-derived surface carboxylate groups and fluorescent dye cargoes.38 They have investigated these particles for imaging, in cells and in vivo.39–43

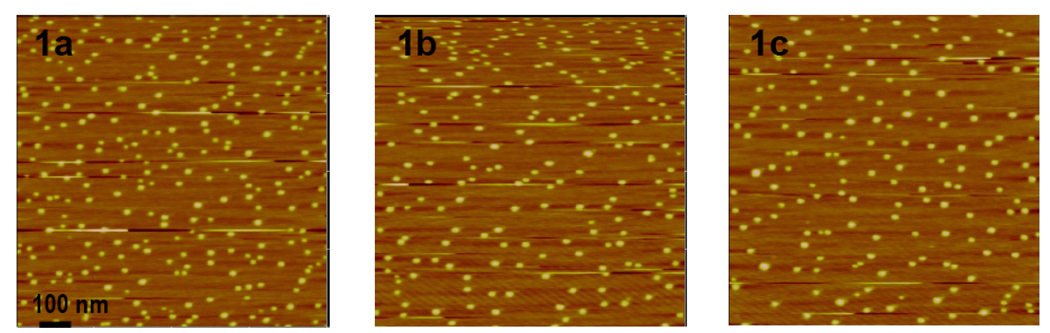

In our work, calcium phosphate nanoparticles encapsulating cassettes 1a – 1c were prepared via Adair’s procedure38 except that a longer reaction time was used (24 h, not 5 min), the particles were purified via MPLC rather than HPLC, and finally a dialysis step was performed to transfer the particles from an ethanolic to an aqueous media. Figure 4 shows AFM images of the particles formed from the cassettes 1; these are quite uniform with diameters around 22 nm.

Figure 4.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) images of cassettes encapsulated calcium phosphate nanoparticles. Avg. particle size: 22 nm.

Spectroscopically, encapsulated cassettes 1a – 1c had absorption and fluorescent spectra that are almost identical to those of the free cassettes in EtOH (see Table 1). The quantum yield of encapsulated 1a –CaNP increased about 30 % relative to the free dye in EtOH, but for 1b-CaNP and 1c-CaNP it decreased by 5- and 2-fold respectively, but is satisfactory for some applications. Throughout, the energy transfer efficiencies were essentially unchanged.

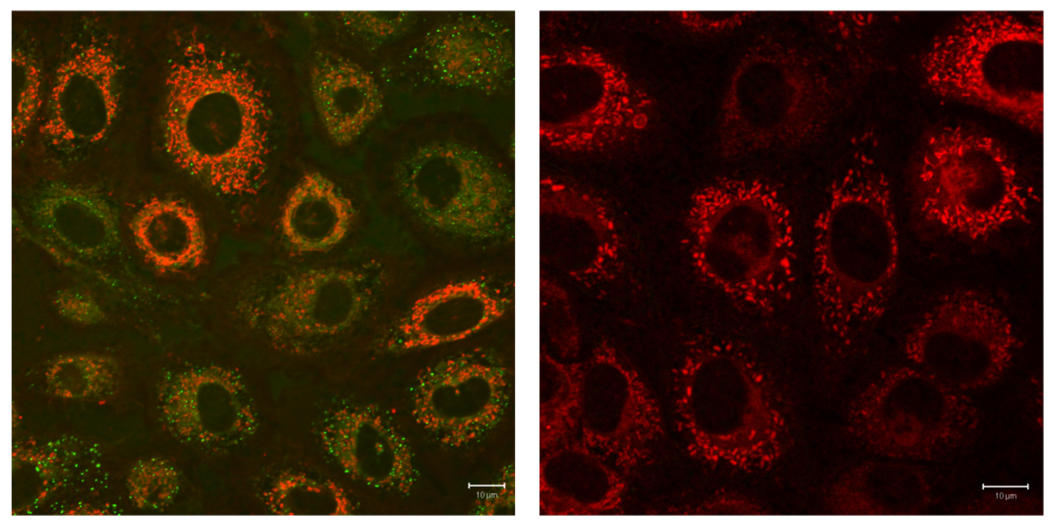

Permeation of The Particles Into Clone 9 Rat Liver Cells

Cassette 1a and 1a-CaNPs were imported in Clone 9 cells at 37 °C to study their subcellular localization. Cassette 1a was observed in different organelles: the mitochondria, the lysosomes, the ER and the cytoplasm. Interestingly, the emission output observed was dependent on the subcellular compartment. Thus, in the mitochondria, perfect energy transfer was observed ie only emission from the cyanine was seen hence the probes fluoresced red. Diffuse green fluorescence was observed in the cytoplasm and ER, and in some bright punctates (lysosomes); the green fluorescence is indicative of emission from the donor part. Conversely, 1a-CaNPs localized only in the mitochondria, and sole emission from the cyanine part was observed, ie the dyes fluoresced red (Figure 5). When the cells were treated with 1a-CaNPs at 4 °C, no fluorescent signal could be observed after 2 h incubation, indicating that the nanoparticles may enter via endocytosis.

Figure 5.

Fluorescence images of cassette 1a (left) and 1a-CaNP (right) in normal rat liver cells (Clone 9). Scale bar is 10 µm.

Conclusions

The research described here represents the first report of coupling BODIPY-based donors with cyanine acceptors in ways that facilitate energy transfer through-bonds. The dispersion of fluorescence emissions from these cassettes is greater than any others prepared by us or, to the best of our knowledge, by others. The observed energy transfer rates for cassettes 1a and 1b are significantly faster than for dipole-dipole coupling in a through-space manner, indicating transfer through bonds is indeed occurring. Overall, they are excellent tools for fluorescence multiplexing in biotechnology.

Syntheses of such cassettes are straight-forward because they are lipophilic. The idea of using water-dispersible nanoparticles to bring lipophilic cassettes into aqueous media, thereby circumventing syntheses of water-soluble materials, is novel, and has the potential to be applied to other donor-acceptor systems where water-soluble modifications would be hard to make. The absorbance and emission maxima of the cassettes and the extent of donor-acceptor energy transfer (E.T.E) remained significantly unchanged after encapsulation into nanoparticles. Conversely, and surprisingly, the fluorescence quantum yields of the three systems studied in this paper were significantly effected. Thus, the fluorescence quantum yield for 1a-CaNPs increased by about 30% relative to the free dye in EtOH, while for 1b-CaNPs and 1c-CaNPs it decreased by 5- and 2-fold respectively. Nanoparticles encapsulating these cassettes may have applications for intracellular imaging, and for observation of parallel macroscopic events in vivo, eg as labels for targeting different cancer forms simultaneously, and allowed specific targeting of organelles. Other applications beyond organelle targeting in cells can now be envisaged.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The TAMU/LBMS-Applications Laboratory directed by Dr Shane Tichy assisted with mass spectrometry, and Prof. A. Tarnovsky and his staff helped with acquiring the transient spectra. Support for this work was provided by The National Institutes of Health (GM72041) and by The Robert A. Welch Foundation (A1121).

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION PARAGRAPH Detailed procedure for the synthesis of the calcium phosphate nanoparticles, their physical properties, rate of energy transfer calculations and cell imaging. This material is available free of charge via Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Sauer M, Hofkens J, Enderlein J. Handbook of Fluorescence Spectroscopy and Imaging: From Ensemble to Single Molecules. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sabnis RW. Handbook of Biological Dyes and Stains. Synthesis and Industrial Applications. Hoboken: Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levenson RM, Mansfield JR. Cytometry. 2006;69:748–758. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haney SA. High Content Screening: Science, Techniques and Applications. Hoboken: Wiley-Interscience; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delmotte C, Delmas A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:2989–2994. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00512-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor DL, Haskins JR, Giuliano KA. High Content Screening: A Powerful Approach to Systems Cell Biology and Drug Discovery. Vol. 356. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montalti M, Credi A, Prodi L, Gandolfi MT. Handbook of Photochemistry. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press-Taylor & Francis; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L, Tan W. Nano Lett. 2006;6:84–88. doi: 10.1021/nl052105b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 3rd ed. New York: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romieu A, Brossard D, Hamon M, Outaabout H, Portal C, Renard P-Y. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:279–289. doi: 10.1021/bc7003268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forster T. Naturwissenschaften. 1946;6:166–175. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laia CAT, Costa SMB. Chemical Physics Letters. 1998;285:385–390. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu L, Soper SA. Rev. Fluoresc. 2006;3:525–574. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Second ed. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loudet A, Burgess K. In: Handbook of Porphyrin Science: With Applications to Chemistry, Physics, Materials Science, Engineering, Biology and Medicine. Kadish K, Smith K, Guilard R, editors. World Scientific; 2010. p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulrich G, Ziessel R, Harriman A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:1184–1201. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziessel R, Ulrich G, Harriman A. New J. Chem. 2007;31:496–501. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loudet A, Burgess K. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:4891–4832. doi: 10.1021/cr078381n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mishra A, Behera RK, Behera PK, Mishra BK, Behera GB. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:1973–2011. doi: 10.1021/cr990402t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozhalici-Unal H, Pow CL, Marks SA, Jesper LD, Silva GL, Shank NI, Jones EW, Burnette JM, III, Berget PB, Armitage BA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12620–12621. doi: 10.1021/ja805042p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burgess K, Burghart A, Chen J, Wan C-W. Proc. SPIE-Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. Vol. 3926. San Jose, CA: 2000. pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burghart A, Thoresen LH, Chen J, Burgess K, Bergstrom F, Johansson LB-A. Chem. Commun. 2000:2203–2204. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiao G-S, Thoresen Lars H, Burgess K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14668–14669. doi: 10.1021/ja037193l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wan C-W, Burghart A, Chen J, Bergstroem F, Johansson LBA, Wolford MF, Kim TG, Topp MR, Hochstrasser RM, Burgess K. Chem.--Eur. J. 2003;9:4430–4441. doi: 10.1002/chem.200304754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burgess K. U.S. Patent 2005/0032120 A1. US: The Texas A&M University System, USA; US Patent No. US2005/0032120 A1. 2005;Vol:7.

- 26.Bandichhor R, Petrescu AD, Vespa A, Kier AB, Schroeder F, Burgess K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10688–10689. doi: 10.1021/ja063784a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim TG, Castro JC, Loudet A, Jiao JGS, Hochstrasser RM, Burgess K, Topp MR. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2006;110:20–27. doi: 10.1021/jp053388z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jose J, Ueno Y, Wu L, Loudet A, Chen H-Y, Son DH, Burgess K. Chem. Commun. 2009 submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu L, Loudet A, Barhoumi R, Burghardt RC, Burgess K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9156–9157. doi: 10.1021/ja9029413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polyansky DE, Danilov EO, Voskresensky SV, Rodgers MAJ, Neckers DC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13452–13453. doi: 10.1021/ja053120l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis WB, Svec WA, Ratner MA, Wasielewski MR. Nature. 1998;396:60–63. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim D, Osuka A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:735–745. doi: 10.1021/ar030242e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montes VA, Perez-Bolivar C, Estrada LA, Shinar J, Anzenbacher P., Jr J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12598–12599. doi: 10.1021/ja073491x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montes VA, Perez-Bolivar C, Agarwal N, Shinar J, Anzenbacher P., Jr J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12436–12438. doi: 10.1021/ja064471i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bisht S, Bhakta G, Mitra S, Maitra A. Int. J. Pharm. 2005;288:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altinoglu EI, Russin TJ, Kaiser JM, Barth BM, Eklund PC, Kester M, Adair JH. ACS Nano. 2008;2:2075–2084. doi: 10.1021/nn800448r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan TT, Muddana HS, Altinoglu EI, Rouse SM, Tabakovic A, Tabouillot T, Russin TJ, Shanmugavelandy SS, Butler PJ, Eklund PC, Yun JK, Kester M, Adair JH. Nano Lett. 2008;8:4108–4115. doi: 10.1021/nl8019888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altinoglu EI, Russin TJ, Kaiser JM, Barth BM, Eklund PC, Kester M, Adair† JH. ACS Nano. 2008:2075–2086. doi: 10.1021/nn800448r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgan TT, Muddana HS, lu EIA, Rouse SM, Tabakovic A, Tabouillot T, Russin TJ, Shanmugavelandy SS, Butler PJ, Eklund PC, Yun JK, Kester M, Adair JH. Nano Lett. 2008;8:4108–4115. doi: 10.1021/nl8019888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muddana HS, Morgan TT, Adair JH, Butler PJ. Nano Lett. 2009:1559–1566. doi: 10.1021/nl803658w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kester M, Heakal Y, Fox T, Sharma A, Robertson GP, Morgan TT, Altinoglu EI, Tabakovic A, Parette MR, Rouse S, Ruiz-Velasco V, Adair JH. Nano Lett. 2008;8:4116–4121. doi: 10.1021/nl802098g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta R, Mishra P, Mittal A. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2009;9:2607–2615. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2009.dk21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glowka E, Lamprecht A, Ubrich N, Maincent P, Lulek J, Coulon J, Leroy P. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:2546–2552. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/17/10/018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.