Abstract

Background:

The conventional lumbar sympathectomy procedure through the extraperitoneal route requires a muscle cutting-splitting incision, which leads to significant postoperative pain and prolonged convalescence. With increasing experience in retroperitoneoscopic procedures, we did a pilot study to explore the role of retroperitoneoscopy in lumbar sympathectomy. We describe herein our technique used for the surgery.

Methods:

The patient was placed in a lateral position. A 15-mm incision was made just below the 12th rib, and retroperitoneal space was created using blunt finger dissection. A custom-made, large balloon was inserted and inflated with the equivalent of 750 mL to 1000 mL of saline. The second 10-mm port was placed in line with the first port above the iliac crest. The third and fourth 5-mm ports were placed anterior to the first 2 ports. Peritoneum was retracted anteriorly. The medial border of the psoas muscle was used as a landmark and a chain identified immediately medial to it. Lumbar vessels were ligated on the right side. The first to fourth lumbar sympathetic ganglia were removed with the intervening chain. The port sites were closed without a drain.

Results:

We attempted and successfully completed this procedure in 8 patients; 6 on the left side and 2 on the right side. The average operating time was 38 minutes. The mean hospital stay was 1.5 days. All patients had symptomatic pain relief and clinical improvement.

Conclusions:

Retroperitoneoscopic lumbar sympathectomy is a safe and effective procedure. It has a short convalescent time and minimal morbidity; hence, it is a viable alternative for the open procedure.

Keywords: Buerger's disease, Retroperitoneoscopy, Sympathectomy

INTRODUCTION

Buerger's disease is characterized by peripheral ischemia of an inflammatory nature with a self-limiting course. Shionoya's criteria1 for the diagnosis of Buerger's disease are (1) smoking history; (2) onset before age 50; (3) infrapopliteal arterial occlusion; (4) either upper limb involvement or phlebitis migrans; (5) absence of atherosclerotic risk factors other than smoking. Confident clinical diagnosis of Buerger's disease may be made only when all 5 requirements have been met.

Buerger's disease is the most common cause of peripheral vascular disease (PVD) in India. Contrary to that in Western countries where it accounts for 0.5% to 12% of all peripheral vascular diseases, it constitutes 45% to 63% in India.2 The majority of patients present with an advanced stage of ischemia; hence, most of them require surgical intervention in the form of either lumbar sympathectomy, omentopexy, or major or minor amputations.

Recent times have seen rapid development in laparoscopic procedures, so much so, that almost all intraperitoneal procedures are being done by minimally invasive techniques. However, the development of retroperitoneoscopy has been slow compared with that of transperitoneal laparoscopy. This is because of the inability to produce pneumoretroperitoneum with direct introduction of a Veress needle in the retroperitoneum.3, 4 Introduction of balloon dissection techniques of the retroperitoneum by Gaur5 has opened up new horizons in the field of retroperitoneoscopy. Consequently, all the retroperitoneal organs are amenable to retroperitoneoscopic surgery. The improvement in optics and availability of better instruments now provides a bright, high-resolution magnified image so that the anatomy is more visible than in open surgery.6

A Medline search yielded very few articles related to retroperitoneoscopic lumbar sympathectomy, and therefore the procedure is neither standardized nor widely practiced, which could partly be because of the relative rarity of Buerger's disease in the Western Hemisphere. Because of sufficient experience gained by us in retroperitoneoscopic surgery pertaining to the kidney, ureter, and adrenal gland, our surgical team became quite familiar with anatomic dissection of the retroperitoneum; hence, it was considered appropriate to perform and standardize the procedure of retroperitoneoscopic lumbar sympathectomy.

METHODS

Between June 2001 and February 2002, 8 patients presenting with symptoms and signs of advanced ischemia of the lower limb were included in the study. Their clinical information is summarized in Table 1. All patients were smokers and presented with progressive disease despite being managed conservatively.

Table 1.

Clinical Profile of Cases Included in the Study*

| Clinical Parameter | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 35 | 32 | 38 | 27 | 35 | 42 | 40 | 35 |

| Duration of Smoking (Years) | 8 | 12 | 16 | 8 | 17 | 22 | 30 | 12 |

| Side | Left | Right | Left | Left | Left | Right | Left | Left |

| Rest Pain | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Ulcer | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Digital Gangrene | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Operative Time (Minutes) | 32 | 54 | 56 | 35 | 32 | 35 | 22 | 30 |

| Hospital Stay (Days) | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Work Absenteeism (Days) | 7 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 14 | 6 | 9 |

All patients were male.

All patients were male with age ranging from 27 to 42 years, with a mean age of 35.5 years. History of smoking ranged from 8 to 30 years (mean, 16 years). All patients were treated previously with conservative management, but most of them did not quit smoking or stopped temporarily.

Clinical examination showed involvement of the distal arteries of the lower limb, with palpable femoral and popliteal arteries on both sides. Pulses distal to the popliteal artery were absent in all patients. A duplex Doppler scan revealed normal vasculature up to the popliteal artery with complete block distally. Keeping in mind the prolonged history of smoking, the typical clinical presentation, and the findings of the Doppler scan, these patients were labeled as having Buerger's disease of the lower limb and angiography was not considered necessary.

The patients had hemoglobin in the range of 9 g/dL to 12 g/dL. Total serum proteins were in the normal range, while serum albumin was in a lower normal range.

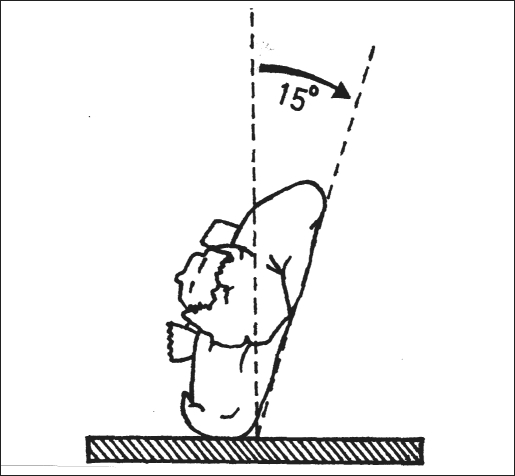

All the procedures were performed with the patient under general anesthesia with muscle relaxation and assisted ventilation. The patient was placed in a lateral position with a 15° to 20° inclination from the vertical axis towards the back (supine position), and the patient was supported with sandbags and strapped across the pelvis (Figure 1). The kidney bridge was elevated, and the table was separated by 20° to increase the space available between the last rib and the iliac crest. The lower leg was flexed, and the upper leg was kept extended to flatten the psoas muscle. A 15-mm incision was made just below the tip of 12th rib (Figure 2). Abdominal flank muscles were visually divided by using cautery. Illumination of the surgical field was enhanced with the fiber-optic light cord of the laparoscope. Dorsolumbar fascia was incised, and the index finger was introduced in the retroperitoneum. Blunt finger dissection was carried out between the posterior surface of Gerota's fascia and the psoas muscle, enough to accommodate a large balloon dissector.

Figure 1.

Patient in lateral position with a 15° to 20° inclination from the vertical axis towards the back.

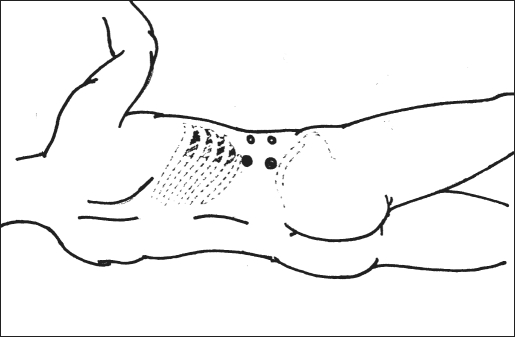

Figure 2.

Port sites.

A ready-made, kidney-shaped, trocar-mounted, silicon balloon dissector was introduced into the space created earlier. The balloon was inflated with air to the equivalent of 750 mL to 1000 mL of saline, and distention could be monitored via a laparoscope introduced through the trocar into the transparent balloon which was kept inflated for 3 to 5 minutes to achieve good hemostasis. The deflated balloon was withdrawn and peritoneum was further stripped from the transversalis fascia using a 0° laparoscope with counterpressure from the left hand. Adequate stripping of peritoneum is necessary to prevent its penetration during port insertion.

The first port was used for the laparoscope after tightening the incision around the 10-mm port by taking 2 sutures through the muscles and reinforcement with purse-string sutures through the skin to prevent gas leakage. The second 10-mm port was placed just above the iliac crest in line with the first port. The third and fourth 5-mm ports were placed anterior to the first 2 ports in such a manner that the 4 ports formed a rectangle (Figure 2). The 3 secondary ports were placed with finger guidance in which the trocar was introduced over the tip of the index finger to avoid injury to any vital tissue.

Pneumoretroperitoneum was created up to 15 mm Hg.

The peritoneum was retracted anteriorly with a 5-mm retractor. Exposed psoas muscle was the most important landmark. The ureter was automatically swept anteriorly with the peritoneum. Blunt dissection was carried out from the superior attachment of the psoas muscle to the common iliac vessels inferiorly with Mixter forceps and a suction cannula to define the medial border of the psoas muscle.

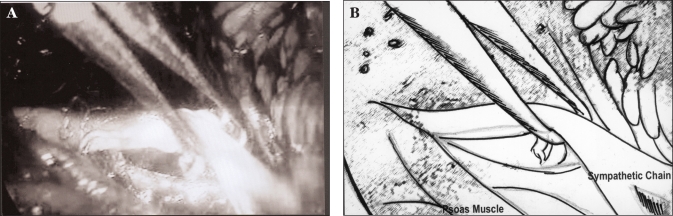

The lumbar sympathetic chain on the left side lies just medial to the medial border of the psoas. Lateral retraction of the muscle fibers exposes the sympathetic chain. Ganglia and rami communicantes were easily seen. The chain was hooked near the L3 ganglion with a 5-mm Endo-Babcock; rami were divided with cautery and a hook dissector, which released the chain (Figure 3). Then dissection was carried out inferiorly, the L4 ganglion lying behind the common iliac vessels was identified, and the chain was divided distal to it. The divided chain was retracted anterosuperiorly, and cephalad dissection was carried out after retracting the kidney anteriorly. Although ganglia can be identified easily in laparoscopic surgery, superiorly glistening fibers of the crus of the diaphragm running obliquely act as a landmark for the L1 ganglion. The chain was divided superior to the L1 ganglion, and the L1 to L4 ganglions along with the intervening chain were removed for unilateral sympathectomy.

Figure 3.

Photograph (A) and schematic representation (B) of sympathetic chain held with endo-babcock forceps.

On the right side, lumbar veins were ligated with 3-0 Vicryl on the vena caval side and clipped on the lateral side. The vena cava was exposed on the lateral side only and kept attached to the peritoneum on the anterior and medial side. This helps in retraction of the vena cava along with peritoneum. Peritoneum was retracted medially along with the vena cava, and the lumbar chain was exposed. The rest of the procedure was carried out as described earlier.

The chain was removed through the 10-mm port. Two 10-mm ports were used interchangeably for visualization and dissection. The port sites were closed without a drain.

RESULTS

The study included 8 male patients, aged 27 to 42 years, with a mean age of 35.5 years. Two patients had right-sided disease, and 6 patients had left-sided disease. The indications for lumbar sympathectomy were resting pain in 4 patients, nonhealing ulcer in 2 patients, and digital gangrene in 2 patients.

All cases were completed retroperitoneoscopically, and no conversion to open surgery was required. No peritoneal tear or other intraoperative complications occurred. The operating time for the first case was 72 minutes and steadily decreased with mean time for all the cases being 38 minutes. All patients had immediate warming of the limb. The chain was also confirmed histopathologically in all cases. All patients were allowed oral feeds on the first postoperative morning. The postoperative stay ranged from 1 to 3 days with an average in-hospital stay of 1.5 days. Postoperative analgesics were given only on demand. No patient required analgesics for operative wound pain after the first postoperative day. All patients were satisfied with the small incisions, minimal postoperative pain, and fast recovery. No significant complications were seen in any patients. Though the wound was closed in all patients without a drain, no hematoma or seroma was encountered postoperatively. All patients made a fast recovery and returned to work between 1 to 2 weeks after surgery.

Postoperatively, immediate improvement occurred in skin warmth on palpation in all the patients, though no objective assessment of skin temperature was made. The 4 patients with resting pain reported marked improvement in pain with a complete disappearance of pain at the end of 1 week. The nonhealing ulcers of the other 2 patients healed spontaneously in the next 3 weeks. Two patients, who presented with digital gangrene, had amputation of the toes at the metatarso-phalangeal joints. One of them had amputation of the big toe, whereas the other had amputation of the first 2 toes. The amputated stumps healed uneventfully.

Follow-up of all the 8 patients has ranged from 12 to 19 months. No recurrence of disease in any patient has been noted; and so far, none has required a major amputation.

DISCUSSION

Though laparoscopy is a familiar procedure, it makes sense that a retroperitoneal organ should be approached by the retroperitoneal route only. It provides the shortest route and direct access to retroperitoneal organs.7 However, a few basic problems to be dealt with while performing retroperitoneoscopic surgery are the limited working space, the absence of landmarks, and prevention of peritoneal penetration.

Placement of a large balloon after making a space over the psoas muscle with the finger and inflating it with 750 mL to 1000 mL of medium provided adequate working space. The balloon can be inflated either with air or saline. Relative advantages and disadvantages of either medium have not been proven so far; hence, it is a matter of personal choice. However, overdistension of the balloon should be avoided because it may have a potential adverse hemodynamic effect and may tear the peritoneum.8 Some authors prefer retroperitoneal dissection without a balloon using only the index finger, which provides adequate space and decreases operating time by 10 to 15 minutes required for balloon dissection.9

Leakage of gas into the parities leading to subcutaneous emphysema could be a cumbersome problem, which can be avoided by tightening the muscles around the port, which is subsequently reinforced by applying a purse-string suture in the skin.10 We found the Tristar port (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., Cincinnati, OH) particularly useful for retroperitoneal procedures, which have a conical sleeve with a flange around the port, which snugly fits into the incision thereby preventing separation of muscles and consequent leakage of gas into the parities.

To ensure safe placement of secondary ports under endoscopic guidance, it is essential that the entry of the port be monitored under direct vision with a laparo-scope. This is not easy in a constrained retroperitoneal space, which requires placement of ports closer to each other and also because of the fact that the adjacent undersurface of the flank abdominal wall cannot be adequately visualized endoscopically despite placing considerable torque on the laparoscope.11, 12 To overcome this problem, we prefer to place the secondary ports with finger guidance, with a trocar in 1 hand and the index finger of the opposite hand placed in the retroperitoneum acting as a guard. All 3 secondary ports were placed under finger guidance before creating pneumoretroperitoneum. In our study, no peritoneal penetration occurred. This could be because after balloon dissection, peritoneum was further stripped off the parities by using blunt dissection with a 0° telescope and counterpressure with the opposite hand.

Due to the absence of landmarks, orientation is also a major problem in retroperitoneoscopy, which can be improved if the camera assistant stands on the same side as the surgeon. The only constant landmark is the psoas muscle. In retroperitoneoscopic lumbar sympathectomy, one should clearly define the medial border of the psoas muscle and follow it up superiorly up to the crus of the diaphragm and inferiorly up to the iliac vessels. The ureter is invariably swept forward with peritoneum, but if visible also acts as a landmark.

In left-sided lumbar sympathectomy, the aorta can be a major landmark; however, we feel exposure of the aorta should be avoided, as it necessitates exposure of paraaortic lymph nodes, which often have vascular adhesions around them due to recurrent foot infections, and these adhesions often lead to cumbersome ooze. For right-sided lumbar sympathectomy, lumbar veins can either be clipped or ligated. The inferior vena cava is meticulously dissected, and only its lateral side is exposed. Anterior and medial sides of inferior vena cava are kept attached to the peritoneum, so that after creation of pneumoretroperitoneum and retraction of peritoneum, the inferior vena cava is easily retracted to the desired position.

We prefer to start dissection of the lumbar chain at the level of the L3 ganglion as it lies in line with the dissecting port. Subsequently, the chain is dissected downwards to the L4 ganglion, and retraction of the divided chain antero-superiorly helps in further dissection of the rest of the ganglia and chain. Although the magnified view provided by the laparoscope gives an excellent display of ganglia and rami, iliac vessels inferiorly and oblique running shiny glistening fibers of crus of the diaphragm act as important landmarks for L4 and L1 ganglia, respectively.

Because the patients in our study belonged to the low socioeconomic strata, they had practically no fat in the retroperitoneum, making stripping of peritoneum a bit difficult in a few cases. Also, because of walking barefoot and recurrent foot and lower limb infections, they occasionally had fibrous adhesions, which had to be sharply divided while stripping the peritoneum. For the same reasons, the lymph node chain was also enlarged, but it never posed a technical difficulty during dissection of the chain. Because the lumbar sympathetic chain lies lateral to the para-aortic and para-caval lymph node chain, the dissection should not be carried over the lymph nodes; otherwise, cumbersome ooze is likely to ensue. The ureter never needed to be stripped separately because it was retracted while stripping the peritoneum.

Like other retroperitoneoscopic procedures, this procedure has a steep learning curve. Though we operated on a small series of 8 cases only, experience gained by us in other retroperitoneoscopic procedures was very valuable. The mean operating time in our study was significantly less than that of other studies with an average operating time of 38 minutes13, 14. Despite limited experience, it has required less time than open surgery and transperitoneal laparoscopic sympathectomy.

No significant complications were encountered in the study. Postoperative pain at the operation site was negligible and so was the need for analgesia. The patients were discharged within 1 to 2 days and returned to work after 1 week. Our patients were from a low socioeconomic strata; therefore, the quick return to work was a clear advantage over the longer recuperation time required after open surgery.

Follow-up of the patients ranging from 12 to 19 months has not revealed recurrence of the disease, which proves the efficacy of retroperitoneoscopy as an alternative to conventional procedures.

CONCLUSION

Despite limited experience with this procedure, retroperitoneoscopic lumbar sympathectomy is a safe and effective procedure for patients with advanced Buerger's disease requiring lumbar sympathectomy. It has a short convalescent time with minimal morbidity. It appears to be a viable alternative to open procedures.

References:

- 1. Shionoya S. Diagnostic criteria for Buerger's disease. Int J Cardiol. 1998;66:243–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olin JW. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger's disease). N Engl J Med. 2000;343:864–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wickham JEA, Miller RA. Percutaneous renal access. In: Wickham JEA, ed. Percutaneous Renal Surgery. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1983:33–39 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clayman RV, Kavoussi LR, McDougall E M, et al. Laparoscopic nephrectomy: a review of 16 cases. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1992;2(1)29–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gaur DD. Laparoscopic operative retroperitoneoscopy: use of a new device. Urology. 1992;148:1137–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wattanasirichaigoon S, Katkhouda N, Ngaorungsri U. Totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic lumbar sympathectomy: an initial case report. J Med Assoc Thai. 1996;79(1):49–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gill IS, Clayman RV, Albala DM, et al. Retroperitoneal and pelvic extraperitoneal laparoscopy: an international perspective. Urology. 1998;52(4):566–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eden CG. Point of technique: operative retroperitoneoscopy. Br J Urol. 1995;76:125–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rassweiler JJ, Seemann O, Frede T, Hankel TO, Alken P. Retroperitoneoscopy: experience with 200 cases. J Urol. 1998;151:927–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gaur DD. Retroperitoneal laparoscopy: some technical modifications. Br J Urol. 1996;77:304–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gill IS, Grune MT, Munch LC. Access technique for retroperitoneoscopy. J Urol. 1996;156:1120–1126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gill IS. Retroperitoneal laparoscopic nephrectomy: the craft of urologic surgery. Urol Clin North Am. 1998;25(2):343–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wattanasirichaigoon S, Wanishayathanakorn A, Ngaorungsri U, Hutachoke Laparoscopic transperitoneal lumbar sympathectomy: a new approach. J Med Assoc Thai. 1997;80(5):275–281 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elliott TB, Royle JP. Laparoscopic extraperitoneal lumbar sympathectomy: technique and early results. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66(6):400–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]