Abstract

During our day-to-day practice, we, as clinicians, occasionally come across patients whose symptomatology is atypical. In major teaching hospitals, it is usually easy to consult with other specialists to optimize patient management and standard of care. Our study patients were treated by the authors between January 1998 and January 2003. In this article, the authors report on 6 different cases of unexpected causes of pelvic pain, all of which were managed in a general gynecological unit at a major tertiary referral institution.

Keywords: Unexpected, Causes of pelvic pain, Gynecological

CASE 1

The first patient was MJF, a 19-year-old university student, para 0+0, who had been sexually active for 2 years. For 18 months, She had been experiencing dull, constant right iliac fossa pain that was not related to her menstruation. The pain had become progressively worse for the 3 months prior to consultation. Laparoscopy was performed in early November 1999, and the appendix exhibited “angry” looking serosa. Laparoscopic appendectomy was performed as per our routine with 2 successive Endoloop Vicryl 0 sutures applied on the cecal side of the appendix flush to the base of the appendix and one suture applied distally to prevent the appendicular contents from soiling the peritoneal cavity. After the appendix was excised, threadworms were seen clearly on the operating screen. Histology confirmed threadworm infestation, fibrous obliteration of the tip of the appendix, and congestion of the wall of the appendix.

Postoperative treatment of the patient and her sexual partner was accomplished by using pyrantel embonate (Combantrin, Pfizer, Australia) and instruction regarding personal hygiene to prevent reinfestation. Follow-up for 3 years showed no recurrence of her symptoms.

CASE 2

LO, a 44-year-old woman, para 2+0, has 2 children aged 22 and 20, both delivered by cesarean delivery. She had been experiencing menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, and dyspareunia for 3 years, and the problems were not responding to medical treatment. In view of the 2 previous cesarean delivery scars, minimum cervical decent and suspected pelvic adhesions, she was scheduled for laparoscopic hysterectomy. The procedure was performed in December 1998. At her 6-week checkup, the patient reported uneventful sexual intercourse following the operation.

In August 2000, she was in the gynecology outpatient clinic and reported constant lower abdominal pain that had started about 6 months following the initial surgery and was getting progressively worse. Laparoscopic examination revealed cystic adherent ovaries. Laparoscopic ureterolysis and adhesiolysis were performed and followed by removal of both adnexa on either side. Ultrasound scan showed that she had a retroperitoneal swelling about 5-cm long on her left side caudal to the former Pouch of Douglas. Examination while she was under anesthesia revealed a swelling that was firm and of cystic consistency. The swelling was dissected and removed laparoscopically. Histological examination revealed a small uterus and cervix. Consultant pathologists met and reexamined the specimens in 1998 and confirmed the completeness of the uterus, the full endo and ectocervix. The second specimen was thought to represent a Mullerian tube anomaly.

The postoperative checkup revealed no more abdominal pain; the pathology report was explained to the patient to allay her apprehension. She was seen in 6 months, for further follow-up by her family physician.

CASE 3

MD, a 57-year-old woman, para 3+0, with children aged 35, 33 and 28, all delivered by spontaneous vaginal deliveries had been experiencing lower abdominal discomfort and uterovaginal prolapse for a few years. She underwent a vaginal hysterectomy and pelvic floor repair in June 1999, and on the first postoperative day, she was losing urine from the vagina, which was noticed when the vaginal pack was removed. A consultant urologist assessed the patient's condition. Ultrasound scan and cystograms were performed, and these did not show any definite evidence of fistulae. However, in view of the persistent loss of urine from the vagina, cystoscopy was performed, which showed that a foreign body was protruding through the urinary bladder wall. Laparotomy was performed and a Graviguard intrauterine contraceptive device was retrieved. It had partly penetrated through the urinary bladder. The walls of the bladder, at that point, were heavily covered by omentum. Adhesions were freed, the bladder wall mobilized, and fistula sutured in layers.

At 6-week postoperative checkup, the patient was questioned about the intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD). She said that she was fitted with an IUCD 29 years earlier, and she lost the device and became pregnant a year later. She could not recall experiencing lower abdominal pain immediately following the insertion of the intrauterine contraceptive device.

CASE 4

JA was a 46-year-old, multiparous women who had been experiencing mild to moderate pelvic pain and deep dyspareunia for 6 months. A pelvic examination revealed a tender Pouch of Douglas. Laparoscopy was performed, and no other pelvic-abdominal abnormalities were diagnosed during the initial laparoscopic assessment. Small spots of Pouch of Douglas endometriosis were excised laparoscopically. The procedure was performed via quadruple port of entry because adhesions were expected in view of her previous history of multiple laparoscopies and laparotomies. Palmer's point of initial entry (left upper abdominal quadrant) and three 5-mm trocars were introduced into each iliac fossa (A and B) and one midway between the umbilicus and the upper end of the bladder (C). These were introduced under laparoscopic guidance. The operation was uneventful.

The patient experienced considerable postoperative lower abdominal pain and discomfort so that she stayed in the hospital for 2 more days. She was subsequently read-mitted on 2 more occasions in as many months. During each of these readmissions not only did the gynecology team assess the patient, but also general surgeons, gastroenterologists, and anesthetists with special interest in postoperative pain management did as well. Because the pain did not subside 3 months following the initial surgery, laparoscopy was performed. At laparoscopy, the omentum and part of a loop of small intestines were adherent to the peritoneum of the anterior abdominal wall at the site of the “C” point of entry.

CASE 5

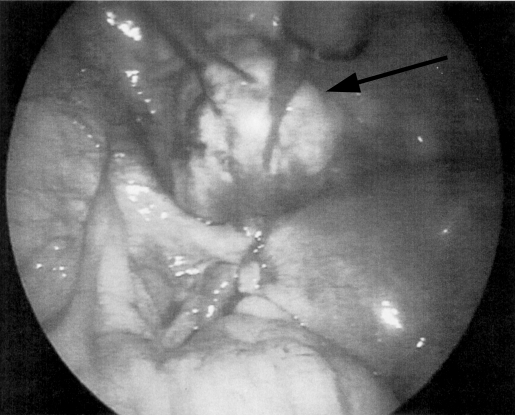

CB was a 47-year-old woman with 2 children aged 24 and 22 years. Her main problem was left iliac fossa pain and discomfort gradually increasing over the previous 6 months. Ultrasound scanning showed a left ovarian mass of mixed echogenicity that measured 7.2 cm x 6.7 cm x 4.3 cm. She consented to operative laparoscopy to remove her ovarian mass. Laparoscopy showed a completely normal left ovary and a large left round ligament leiomyoma (fibroma) (Figure 1). The leiomyoma was removed laparoscopically, and the patient reported alleviation of her pain since the performance of the procedure 2 years ago.

Figure 1.

Round ligament fibroma (leiomyoma).

CASE T 6

RS was a 34-year-old patient, para 3+0, with children aged 18, 13, and 11. The middle child was born by cesarean delivery.

Her main problem was right iliac fossa pain for 6 weeks: she was regularly menstruating and serum B-HCG was negative in 2 tests 1 week apart. Ultrasound scanning was performed and showed a complex swelling, partly cystic and partly solid in the right adnexa extending to the Pouch of Douglas. The lesion measured 6 cm x 3 cm x 5 cm. Thinking that this was probably inflammation, her family physician started her on broad-spectrum antibiotics for 2 weeks; despite that, the pain did not improve, nor did the ultrasound findings. A vaginal examination revealed a right adnexal swelling that extended to the Pouch of Douglas.

The patient consented to operative laparoscopy, which showed a clinical picture consistent with an old right fallopian tube ectopic pregnancy. Laparoscopic right salpingectomy was performed as outpatient surgery. Histological examination of the removed specimen showed necrotic chorionic villi consistent with an old right fallopian tube ectopic pregnancy.

The patient became pregnant 6 months later and had a spontaneous vaginal delivery, and then she requested a sterilization procedure.

DISCUSSION

Case 1

Laparoscopic appendectomy is being increasingly performed by gynecologists experienced at complicated operative laparoscopy.1 Stool analysis was not performed preoperatively in this case because this investigation is not routinely done in pelvic pain in teenagers, especially when the patient had no suggestive symptoms like anal and or vaginal itching. The incidence of appendicitis and helminths infestation is higher in children than in teenagers.2 However, histological examination of the removed appendix is usually the key to the diagnosis in these situations.

Case 2

Mullerian tube anomalies are unusual.3 They are least expected in parous women, especially when the patient's pelvis had been examined during cesarean delivery, as in this case. Unfortunately, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was not done,4,5 and ultrasound scanning during her last pregnancy gave no suggestion of genital anomaly. Laparoscopy is a valuable tool to diagnose and treat the condition. During the initial laparoscopic hysterectomy, the rudimentary uterus was missed, and, therefore, not removed. However, in this case, the patient was obese ((body mass index = 37) with relatively dense retroperitoneal fat layers, and the rudimentary uterus was retroperitoneal. In general, if you do not specifically look for something, you will not find it.

Case 3

Vesicovaginal fistula commonly results from obstetric and gynecological surgery.6–9 In this case, the vaginal pack and urinary catheter were removed 24 hours following surgery, and that was followed by dribbling of urine from the vagina, raising clinical suspicion of urinary fistula. During the successful surgical repair of the fistula, a Graviguard intrauterine contraceptive device was accidentally found.

Case 4

Herniation of omentum, intestines, or both, through laparoscopic trocar incisions of 10-mm diameter or more have been reported especially in the midline, if the fascia was not carefully sutured.10 Herniation at 5-mm laparoscopic port sites is rare.11,12 Therefore, most surgeons do not routinely close 5-mm post sites, believing that such fascial defects are not large enough to create a significant risk of hernia formation, thus not justifying the extra time and effort needed to close them. However, one has to remember that repetitive motions in different directions in laparoscopic surgery may cause the 5-mm defect to enlarge significantly, allowing a hernia to develop.13 In this case, herniation and adhesions of the omentum and a small part of a loop of small intestine were unexpected. The condition was successfully treated under laparoscopic guidance.

Case 5

Round ligament leiomyomata are rather uncommon. They may mimic other mass lesions in this vicinity including ovarian masses (as in this patient), adenopathy, and inguinal hernias. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography are more accurate than ultrasound scanning in localizing and defining the lesions.14,15 However, ultrasound scanning is more widely available and less costly to perform.

Case 6

The first step in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is demonstration of pregnancy by means of a widely available and sensitive qualitative test for the beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (beta hCG). A negative pregnancy test will generally be used to exclude ectopic pregnancy.16 However, this is the second case of histo-logically confirmed ectopic pregnancy, reported by the same authors.17 Serum beta-hCG was 1 U/L, a value less than the lower limit of detecting the highly sensitive qualitative serum test whereby the pregnancy test was negative and the clinical diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy was correctly made, based on other features.

CONCLUSION

We believe that regular review of unusual and unexpected presentations are important facets of quality assurance and the adoption and maintenance of a healthy system of constructive self-criticism. Clinicians should always endeavor to exchange their experience for the benefit of our patients and the profession in general.18

Contributor Information

Mark Erian, University of Queensland/Royal Women's Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.,.

Glenda McLaren, University of Queensland/Mater Mothers' Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia..

References:

- 1. Kumar R, Erian M, Kimble R, et al. The role of laparoscopic appendectomy in modern gynecology. J Am Ass Gynaecol Laparosc. 2002;9(3):252–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chernysheva ES, Ermaskova GV, Beregina EL. The role of helminthiasis in the aetiology of acute appendicitis. Phisurgiia. 2001;(10):30–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aittonaki K, Eriola H, Kajanoja P. A population-based study of the incidence of Mullerian aplasia in Finland. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(3):624–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hundley AF, Fielding JR, Hoyte L. Double cervix and vagina with deptate uterus: an uncommon Mullerian malformation. Obstet Gynecol. 98(5p62):982–985, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Console D, Tambursini S, Barresi D, et al. The value of the MR imaging in the evaluation of Mullerian duct anomalies. Radiol in Med. 2001;102(4):226–232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Romics I, Kelemen Z, Fazakas Z. The diagnosis and management of vesicovaginal fistulae. BJU Int. 2002;89(7):764–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miller EA, Webster GD. Current management of vesicovaginal fistulae. Curr Opin. 2001;11(4):417–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Flores-Carreras O, Cabrera JR, Galeano PA, et al. Fistulae of the urinary tract in gynaecological and obstetric surgery. Int Urogynaecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(3):203–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hilton P. Vesico-vaginal fistula: New perspectives. Curr Opin Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;13(5):513–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morrison CP, Wemyss-Holden SA, Iswariah H, Maddem GJ. Lateral laparoscopic port sites should all be closed: The incisional “spigelian” hernia. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(9):1364 Epub 2002 Jun 06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang PH, Yen MS, Yuan CC, et al. Incarcerated hernia in a 5-mm vannula wound. J Am Assoc Gynaecol Laparosc. 2001;8(3): 449–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kwok A, Lam A, Ford R. Incisional hernia in a 5-mm laparoscopic site incision. Aust N Z J Obstetric Gynaecol. 2000;40(1): 104–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reardon PR, Preciado A, Scarborough T, et al. Hernia at 5-mm laparoscopic port site presenting as early post-operative small bowel obstruction. Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 1999; 9(6):375–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Warshauer DM, Mardel SR. Leiomyoma of the extraperito-neal round ligament: CT demonstrations clinic imaging. 1999; 23(6):375–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rhee CS, Kim JS, Woo SK, et al. MRI of round ligament leiomyoma associated with Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24(2):202–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kalinski MA, Guso DA. Haemorrhagic shock from a ruptured ectopic pregnancy in a patient with a negative urine pregnancy test result. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40(1):102–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Erian MS, McLaren GR. Double ectopic pregnancy–an unusual presentation. B J C P. 1993;47(3):161–162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Erian M, Goh J, Coglan M. Auditing the complications of laparoscopy in a major teaching hospital in Australia. Gyaecol Endoscosc. 2001;10:303–308 [Google Scholar]