Abstract

Introduction:

Lumbar hernias occur infrequently and can be congenital, primary (inferior or Petit type, and superior or Grynfeltt type), posttraumatic, or incisional. They are bounded by the 12th rib, the iliac crest, the erector spinae, and the external oblique muscle. Most postoperative incisional hernias occur in nephrectomy or aortic aneurysm repair incisions.

Case Report:

We present 2 patients who had undergone flank incisions and subsequently developed significant bulging of that area. The first patient had an atrophy of the abdominal wall musculature while the other had a large lumbar incisional hernia that was repaired laparoscopically.

Discussion:

Lumbar incisional hernias are often diffuse with fascial defects that are usually hard to appreciate. Computed tomography scan is the diagnostic modality of choice and allows differentiating them from abdominal wall musculature denervation atrophy complicating flank incisions. Repairing these hernias is difficult due to the surrounding structures. Principles of laparoscopic repair include lateral decubitus positioning with table flexed, adhesiolysis, and reduction of hernia contents, securing ePTFE mesh with spiral tacks and transfascial sutures to an intercostal space superiorly, iliac crest periosteum inferiorly, and rectus muscle anteriorly. Posteriorly, the mesh is secured to psoas major fascia with intracorporeal sutures to avoid nerve injury.

Conclusion:

Lumbar incisional hernia must be differentiated from muscle atrophy with no fascial defect. The laparoscopic approach provides an attractive option for this often challenging problem.

Keywords: Hernia, Lumbar, Laparoscopic repair

INTRODUCTION

Lumbar hernias are infrequent; they occur in the broad anatomic area bounded superiorly by the 12th rib, inferi-orly by the iliac crest, medially by the erector spinae, and laterally by the external oblique muscle. Lumbar hernias can be congenital or primary, occurring in the inferior lumbar triangle (or Petit type) or in the superior lumbar triangle (or Grynfeltt type), posttraumatic1–3 or incisional. Most postoperative incisional hernias occur in nephrectomy or aortic aneurysm repair incisions, but have also been described following iliac bone graft harvest4,5 and latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap.6 We present 2 cases of lumbar incisional “hernias” and discuss the diagnostic dilemma and the laparoscopic approach to the management of true hernias.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

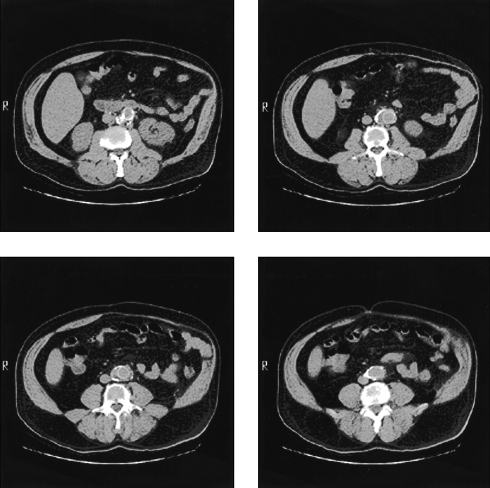

This is a 68-year-old white male with a medical history significant for noninsulin dependent diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease. He underwent an infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm repair via a retroperitoneal approach through a left flank incision 2 years before presentation and subsequently developed a progressively enlarging left flank bulge causing him some discomfort. He was referred to us for repair of his lumbar incisional hernia. On examination, a large bulge in his left flank was noted, significantly accentuated when the patient was standing up, but also present when he was in the dorsal decubitus position. No distinct fascial defect could be palpated. A computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained and showed atrophy of the left rectus muscle and lateral abdominal wall musculature with no evidence of fascial defects or herniation of any intraabdominal content (Figure 1). It was decided in light of these findings not to proceed with any operative interventions.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan showing atrophy of the left rectus muscle and lateral abdominal wall musculature with no evidence of fascial defects or herniation of any intra-abdominal content.

Case 2

This 64-year-old African-American male had undergone a right radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma 3 years before his current presentation. A year later, he was noted to have a right lumbar incisional hernia that was repaired with a polypropylene mesh. Soon after that, the patient had a recurrent bulge in his right flank area requiring him to wear a truss to hold it in and prevent discomfort. He was referred to us for repair of his recurrent lumbar incisional hernia. His medical history was significant for degenerative joint disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, gout and dysrhythmia. He was on fosinopril, diltiazem and amiodarone. He had a history of heavy smoking for 35 years but had quit 5 years earlier. His surgical history also included an open hiatal hernia repair and fundoplication approximately 7 years earlier.

On examination, a right transverse flank incisional scar was noted with a very large bulge that seemed to partially shrink when the patient was lying in a right lateral decubitus position; a clear fascial defect was hard to ascertain by palpation. A well-healed abdominal upper midline incision was noted as well.

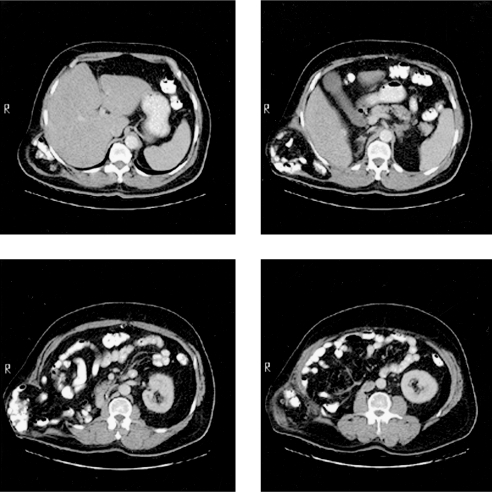

A CT scan was obtained and showed a giant right flank hernia with contrast-containing bowel loops arising from a posterolateral fascial defect and tracking up over the rib cage (Figure 2). The cardiologist was consulted preoperatively and obtained a Holter monitor showing a few premature ventricular contractions and premature atrial complexes as well as an echocardiogram showing an ejection fraction of 55% with mild left ventricular hypertrophy.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan showing a giant right flank hernia with contrast-containing bowel loops arising from a posterolateral fascial defect and tracking up over the rib cage.

A laparoscopic repair was performed, as detailed below, using a 16 x 23-cm ePTFE mesh to cover a 10 x 17-cm hernia defect. The operative time was 195 minutes, and the estimated blood loss was minimal. The patient did well postoperatively and was ambulating, passing flatus, and tolerating a regular diet on the first postoperative day. His postoperative course was complicated however with new-onset atrial fibrillation requiring anticoagulation, which prolonged his hospital stay.

LAPAROSCOPIC LUMBAR HERNIA REPAIR

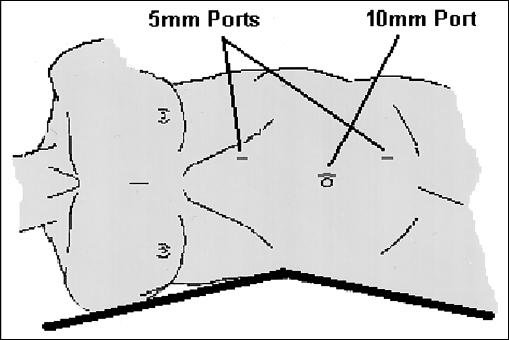

The patient is placed in a lateral decubitus position with the table flexed, opening the space between the rib cage and the iliac crest (Figure 3). This position is crucial not only to expand the operative area, but also to allow lateral truncal mobility after placement and fixation of the mesh. Access to the peritoneal cavity is obtained at the umbilicus using the open technique and pneumoperitoneum is established to a pressure of 15 mm Hg. A 30- or 45-degree angle viewing scope is used. Two additional 5-mm trocars are usually needed in the upper and lower abdomen. Because most of these hernias occur following retroperitoneal access surgery, the hernia contents usually consist of small bowel in addition to the colon herniating in a sliding fashion. The small bowel is usually easily reduced. The colon has to be mobilized by opening the peritoneal reflection, which is usually intact. Gravity allows the colon to retract to the midline. Mobilization should continue posteriorly to the psoas major muscle. At that point the fascial defect is measured and an ePTFE Dual Mesh (W. L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, Arizona, USA) is selected to ensure a 3-cm to 5-cm overlap with normal fascia. The mesh will usually extend to the iliac crest inferiorly and over the diaphragm superiorly. The mesh is secured superiorly with sutures placed through the ninth intercostal space, during full expiration and taking care to avoid the intercostal neurovascular bundle by staying just over the tenth rib. Inferiorly, the mesh is secured with sutures passed though the iliac crest periosteum. These transabdominal permanent sutures (0 Ethibond) are placed every 5 cm and spiral tacks are placed in-between. Posteriorly, the mesh lies over the psoas major muscle. We avoid placing transabdominal sutures in that posterior area to avoid entrapment of the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, or genitofemoral nerves; we instead secure the mesh with sutures to the psoas major investing fascia placed intracorporeally and do not place any spiral tacks in that area.

Figure 3.

Lateral decubitus position with the table flexed, opening the space between the rib cage and the iliac crest.

DISCUSSION

Lumbar incisional hernias are often diffuse with fascial defects that are usually hard to appreciate. They have to be distinguished from abdominal wall musculature denervation atrophy, which can complicate flank incisions. CT scan is the modality of choice in the assessment of the symptomatic patient after flank incision.7,8 In addition to making the diagnosis of hernia, it allows clear assessment of the size of the defect, the different muscle layers, the hernia contents, and any concomitant intraabdominal pathology. Reportedly, 12% to 23% of patients with a flank incision for the retroperitoneal approach of aortic aneurysms develop an uncomfortable and cosmetically displeasing flank “bulge” resulting from laxity of the transversus and oblique abdominal wall musculature9,10 Anatomic and clinical evaluations have elucidated the predominant cause to be an incisional injury to the main trunk of the 11th intercostal nerve.9 The accentuation of the bulge is partially related to the unopposed contraction of the contralateral flank musculature. Long-term follow-up reveals gradual improvement in the unsightliness of the bulge, possibly due to incomplete reinnervation, but not complete resolution. Because no fascial defect exists, this is not a true hernia and surgical correction is not needed other than for cosmetic reasons and is usually difficult and unsatisfactory. Incisional lumbar hernias complicate 7% of retroperitoneal approaches.10 They are difficult to repair due to their location and the surrounding bony structures. Multiple techniques for repair have been suggested. Reconstruction usually includes extensive dissection from the 12th rib to the iliac crest, followed by mobilization of local flaps, plication of normal fascia11 or onlay mesh. Others12 have advocated extensive retroperitoneal dissection with extraperitoneal placement of a large sheet of polypropylene mesh. No procedure has been shown to have a clear advantage over the others, especially in view of the relative rarity of these cases. Recently, the laparoscopic techniques described to repair incisional ventral hernias have been applied to the treatment of lumbar hernias. Authors have reported repairing primary inferior and superior lumbar hernias using laparoscopic13,14 or endoscopic extraperitoneal techniques.15 Others have reported laparoscopic repair of a traumatic lumbar hernia.4 We report here a laparoscopic repair of a recurrent incisional hernia. Our technique uses the same well-described methods for the laparoscopic repair of ventral hernia with certain modifications pertaining to the fixation of the mesh. In the posteromedial area, we advocate fixation of the mesh with intracorporeal suturing to the psoas major muscle and avoiding placement of spiral tacks to prevent entrapment of the nerves that run in that area; this area is the equivalent of the “triangle of doom” in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs. We prefer inferior fixation with transabdominal sutures through the iliac crest periosteum although other authors have used bone screws.16 The laparoscopic repair of incisional lumbar hernias seems to afford all the advantages of minimally invasive surgery in addition to limiting the size of the incision and the extent of the dissection.

Lumbar incisional hernias occur rarely and remain difficult to manage. Computerized tomography is the diagnostic modality of choice and is recommended in all patients with a bulge after a flank incision to differentiate a hernia from muscle atrophy with no fascial defect. As experience with laparoscopic ventral hernia repair grows and long-term results continue to emerge, this minimally invasive approach may become the procedure of choice for repairing these difficult lumbar incisional hernias.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors state having no financial interest in any commercial device, equipment, instrument, or drug that is a subject of the article.

References:

- 1. Barden BE, Maull KI. Traumatic lumbar hernia. South Med J. 2000;93(11):1067–1069 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balkan M, Kozak O, Gulec B, Tasar M, Pekcan M. Traumatic lumbar hernia due to seat belt injury: case report. J Trauma. 1999;47(1):154–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sarela Al, Mavanur AA, Bhaskar A, et al. Post traumatic lumbar hernia. J Postgrad Med. 1996;42(3):78–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burick AJ, Parascandola SA. Laparoscopic repair of a traumatic lumbar hernia: a case report. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1996; 6(4):259–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stevens KJ, Banuls M. Iliolumbar hernia following bone grafting. Eur Spine J. 1994;3(2):118–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moon HK, Dowden RV. Lumbar hernia after latissimus dorsi flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75(3):417–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baker ME, Weinerth JL, Andriani RT, Cohan RH, Dunnick NR. Lumbar hernia: diagnosis by CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148(3):565–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Killeen KL, Girard S, DeMeo JH, Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE. Using CT to diagnose traumatic lumbar hernia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174(5):1413–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gardner GP, Josephs LG, Rosca M, Rich J, Woodson J, Menzoian JO. The retroperitoneal incision. An evaluation of postoperative flank ‘bulge.’ Arch Surg. 1994;129(7):753–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Honig MP, Mason RA, Giron F. Wound complications of the retroperitoneal approach to the aorta and iliac vessels. J Vasc Surg. 1992;15:28–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bolkier M, Moskovitz B, Ginesin Y, Levin DR. An operation for incisional lumbar hernia. Eur Urol. 1991;20:52–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lichenstein IL. Repair of large diffuse lumbar hernias by an extraperitoneal binder technique. Am J Surg. 1986;151(4):501–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heniford BT, Iannitti DA, Gagner M. Laparoscopic inferior and superior lumbar hernia repair. Arch Surg. 1997;132(10): 1141–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bickel A, Haj M, Eitan A. Laparoscopic management of lumbar hernia. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(11):1129–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Postema RR, Bonjer HJ. Endoscopic extraperitoneal repair of a Grynfeltt hernia. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(4):716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Woodward Am, Flint LM, Ferrara JJ. Laparoscopic retroperitoneal repair of recurrent postoperative lumbar hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1999;9(2):181–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]