Abstract

This article discerns the role that Mexican American gang members play in drug markets, and the relationship between gang members’drug use and drug selling in South Texas. A four-part typology based on the two dimensions of gang type and gang member emerged from this qualitative analysis of 160 male gang members: Homeboys, Hustlers, Slangers, and Ballers. Major findings include the following: (1) many gang members are user/sellers and are not profit-oriented dealers, (2) gangs commonly do extend “protection” to drug-selling members, and (3) proximity to Mexican drug markets, adult prison gangs, and criminal family members may play important roles in whether these gang members have access and the profit potential to actually deal drugs. This research contributes to our complex intersections between gangs, drug using, and drug selling.

Keywords: gangs, drug selling and dealing, Mexican Americans

Research on gangs and drug dealing has generally found it difficult to discern the role that gangs and gang members play in drug markets, and the relationship between gang members’ drug use and drug selling behaviors (Howell and Gleason 1999). Studies have reportedly found that most gangs’ major illegal activity is associated with the marketing of drugs, especially in low-income urban minority communities (Moore 1978; Covey, Menard, and Franzese 1992; Chin 1995; Spergel 1995). The degree, however, to which gangs are involved is found to vary from one community to another, often times among gangs within the same neighborhood (Hagedorn 1988; Padilla 1992a; Morales 2001). Most studies, however, have found that even though drug selling is common among individual gang members, it is not a primary focus of the street gang itself (Klein 1995). Rather, drug sales develop almost as an unintended consequence of drug use by gang members as it does among other drug users. This article addresses the various roles of gang members in drug sales, the structure and function of the gangs, and the relationship to other actors in the drug market, especially adult prison gangs. The purpose here is to address an important gap in our knowledge of the gang’s participation in drug market in relationship to other actors.

MEXICAN AMERICAN ILLEGAL DRUG MARKET

In South Texas, the geographic context of this article, marijuana and heroin account for more than half of the total seizures of these drugs in the United States (ONDCP 2002). The Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) pursuant to the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 designated the Southwest Border, which encompasses the entire 2,000 mile border one to two counties deep, as a High Intensity Drug Traffic Area (HIDTA). These are areas that are identified as having the most critical drug trafficking problems that adversely impact the United States. Within the Southwest, South Texas is identified as a primary staging area for large-scale, bi-national, narcotic trafficking operations and a common source of marijuana, cocaine, and heroin.

The business of illegal drugs in South Texas is similar in its structure to those in other regions of the United States (Johnson et al. 1990; Adler 1993). Considering the proximity of Mexico (a few hours drive from several large southwestern U.S. cities) trafficking operations are, however, somewhat different from distribution operations in other regions of the U.S. Drug dealing operations typically involve a bi-national hierarchic structure comprising of Mexican Americans and Mexicans. Mexican Americans living near the U.S./Mexico border and involved in drug distribution have more direct access to primary illegal drug sources than others who must go through multiple layers of middle-men, which decreases profits and increases risks. Cultivating a drug connection in Mexico may also be easier for a Mexican American who may be more acceptable to a Mexican dealer since they share a common ethnic background. This type of access for persons in the Southwest makes it unnecessary for them to develop an organizational hierarchy to traffic in drugs as opposed to those residing in cities and towns located in other areas of the U.S. These factors result in highly decentralized drug markets in the Southwest characterized by multiple small-time drug entrepreneurs with ties to Mexican distributors along with larger international cartels.

One other factor that has begun to characterize the drug market in Mexican American communities in the Southwest is the presence of Chicano prison gangs. Few studies that describe the role of prison gangs in drug sales and their relationship to juvenile and adult gangs outside the prison either in Mexican American communities or others. Jacob’s (1974) study is one of the few to address the prison/street nexus. In that study, however, he describes how inmate culture is actually imported from the outside by street gangs into the prison. What seems to be occurring in U.S. Mexican communities is actually the opposite, adult prison gangs are influencing the community’s illegal activities from inside the prison. The participation of “pintos” (a term used in the barrio by Mexican Americans to describe ex-convicts) in the drug market was initially described in Moore’s Homeboys (1978). At that time in Los Angeles, (and we speculate throughout the Southwest), prison gangs were selling drugs on “ a relatively small-scale” and did “see their business as a lifetime commitment to a deviant role” (Moore 1978:149). Their role in the drug market in states like California and Texas seems to have substantially increased over the last two decades based on reports from law enforcement in these two states (although there is little information on these groups in the academic literature). In the Texas prison system, gang membership grew sub stantially during the 1990s (Cornyn 1999). As members of these prison gangs were released (paroled) from penal institutions, they began to organize themselves into a criminal network engaged in drug dealing and other illegal activities. This same pattern has been reported in California and other states with large concentrations of incarcerated Mexican Americans.

JUVENILE GANGS, DRUG DISTRIBUTION, DEALING, SELLING, AND ORGANIZATION

The term youth gang is used in this study to refer to groups of adolescents1 who engage in collective acts of delinquency and violence, and are perceived by others and themselves as a distinct group. Moreover, the group has a structured hierarchy with rituals, symbols (colors, signs, etc.) and is associated with a territory. Research in the past twenty years has yielded a large amount of data on youth gangs and their role in the distribution of drugs (Fagan 1996; Hagedorn 1994a; 1994b; Klein 1995; Padilla 1992b; Taylor 1990;Venkatesh 1997;Waldorf 1993; Hagedorn, Torres, and Giglio 1998). Dolan and Finney (1984), Moore (1978) and Spergel (1995) have all suggested that youths involved in gang activities are more likely to be involved in the drug trade than other adolescents. During the crack epidemic of the late 1980s and early 1990s, the distribution of this drug was often linked to juvenile drug gangs or “crews” in large U.S. cities like New York and Chicago (Miezkowski 1986; Padilla 1992a; Sullivan 1989;Williams 1989). Taylor (1990) and others have suggested that the growth of gang membership is due to resources made available through the gang’s connection to drug markets. Declining economic conditions in many minority urban communities increased juvenile involvement in illegal drug markets (Hagedorn 1988). In the case of New York City, drug suppliers often used juveniles to retail their wares and avoid the risk of harsh sentences adults faced under the Rockefeller drug laws (Williams 1989).

Many researchers such as Skolnick et al. (1990) have argued that drug dealing by gangs is carried out by highly structured organized crime units. As well, Jankowski (1991:131–32) proposed that gangs were cohesive and structured organizations which all had a relationship with organized crime. Applying contingency theory from the literature on organizations, Hagedorn et al. (1998) explores the relationship between gangs and drug selling among minorities in Milwaukee. His findings show that a gang whose drug sales were limited to people within the neighborhood, i.e. their low-income neighbors, are likely to be less organized as a drug gang than those gangs who sell to people outside the neighborhood, especially to middle-class and affluent Whites.

Most contemporary literature reports youth gangs to be rarely involved in large-scale drug distribution activities as an organized gang function (Decker and Van Winkle 1996; Klein 1995). As described by Howell and Gleason (1999:2), “Distribution implies organizational management and control, as opposed to individual involvement in selling drugs directly to individual buyers.” Waldorf and Lauderback’s (1993) study found Latino and African-American street gangs in San Francisco to be loosely organized with individuals engaged in freelance, rather than organized, drug distribution entities. Skolnick et al. (1990) did find that African-American gangs are more likely to be “instrumental” and vertically organized than “cultural” Latino gangs. In his description, the instrumental gangs are more dedicated to the organized sale of drugs and the cultural gangs are closer to the classic notion of neighborhood corner groups. Mieczkowski (1986) has argued, as well, that crack in Detroit was distributed by small entrepreneurs rather than a large organization.

DRUG USE, DRUG SELLING BEHAVIORS, DRUG DEALING, AND DISTRIBUTION

Research over three decades has established the intersection between different types of illegal drug use and drug selling (Hunt 1990; Hunt, Lipton, and Spunt 1984; Preble and Casey 1969). Users who serve as intermediaries for other users in drug transactions seem to be a consistent phenomenon. This has been observed with some consistency across the different types of illegal drug markets (marijuana, crack, cocaine, heroin) in varied geographic contexts for over 30 years (Andrade, Sifaneck and Neaigus 1999; Furst et al. 1997). For insistence, Sifaneck (1996) has observed a relationship between chronic marijuana users in New York City who played various roles in the distribution, some essentially becoming “subsistence dealers” of the drug in order to pay for their own use.

There have been few noninstitutionalized, or community-based studies of Mexican American drug use and selling/ dealing especially among gang members (Bullington 1977; Moore 1978; Sanders 1994). In Moore’s (1978:85) study of East Los Angeles’ drug market, she states “drug dealers did employ members of their own barrios in a hierarchy that included non-addicted dealers, addicted dealers (who in turn would supply addict-pushers who sold heroin for use rather than profit), and finally the consumer addict.” Individual gang members who dealt drugs operated in the same manner. A consistent finding in these few published studies is that users often paid for their drugs, as Preble and Casey (1969) found among New Yorkers, “by taking care of business,” that is, with involvement in drug sales.

In this study we identify and describe the different types of drug use, selling behaviors, and dealing found among members of 26 active gangs in a large metropolitan area in South Texas. We explore the different dimensions of relationships that are involved in constructing a typology of Mexican American gang membership, and the distribution and use of drugs in the Mexican American illegal drug market. Finally, we discuss the implications of current public policies pertaining to gang formation and drug distribution.

METHOD

This research evolved from a study of Mexican American gangs in South Texas, whose focus was to identify and distinguish the relationship between gang violence and drug use among male gangs. The study used multiple methods, including ethnographic field observations, focus groups, and life history /intensive interviews with 160 male gang members sampled in a large Southwestern city (see Yin et al. 1996). The study was delimited to two areas of the city’s Mexican American population, encompassing centers of commerce and residency for this group. These areas also have the highest concentration of delinquent behavior and Mexican American gang activity as well as underclass characteristics (Kasarda, 1993). This delimitation was based on secondary data such as the U.S. Census, criminal justice data, public housing statistics, and previous published governmental reports and studies.

After identifying two study areas, two indigenous field workers began the social mapping of these communities, using systematic field observations and recording extensive field notes. Using Wiebel’s (1993) indigenous out-reach model, field workers were selected based on their knowledge and familiarity with the targeted community and their ability to provide entrée to groups of Mexican American juvenile gang members. The social mapping stage of the study lasted approximately six months, although field work was a continuous process lasting a total of four years. Social mapping assisted us in the identification of gangs and where the target groups congregate, such as public parks, public housing spaces, playgrounds, recreational centers, downtown areas, neighborhood businesses and specific neighborhoods. In conducting this initial fieldwork, field workers were able to establish “an ethnographic presence” (Sifaneck and Neaigus 2001) and maintain a high visibility within the targeted community to help legitimize the project in the community. After this was accomplished, the field workers began to make contacts with the gang members, gain their trust, and obtain access to their social networks. The primary goals of the fieldworkers were to establish rapport with the gang members, maintain nonjudgmental attitudes, and to promote candid and accurate reporting by respondents during data collection and the interview process.

After gaining access, rapport, and trust, field workers began to collect observational data based on gang hangouts mentioned previously. Results of this fieldwork were recorded in daily field notes that were shared and discussed with the research team. All efforts were made not to use information from school officials or police agencies in order to avoid associating the project with these authorities. Attention was focused on the primacy of developing and maintaining networks and a research presence in these communities and among the gangs in these areas.

The fieldwork resulted in identifying all 26 active juvenile gangs and their respective rosters in this area whose cumulative membership totaled 404 persons. The validity and accuracy of gang rosters were checked using at least three of four collateral sources: “gatekeepers”, gang member contacts, key respondents, and fieldworkers’ observations. Gatekeepers control access to information, other individuals and places (Hammersley and Atkinson 1995, LeCompte and Schensul 1999). Fieldworkers were able to acquire information for initially classifying membership (leader, core, peripherals), gang type, and to delineate the gang’s territory (neighborhood). Using this information, we designed a stratified sample that generated the 160 gang members interviewed for this study. A monetary incentive of $50 was provided to the gang member for participating in the interview. In order to protect the identities of the study participants, actual names of the gangs and gang members were known only to the field workers and the project administrator. Any reference to individual members or organizations was based on pseudonyms or identification number assigned by the administrator. As well, fictitious names were given to all geographic and other physical locations.

For the purpose of this paper emphasis will be on drug selling and drug use pattern information elicited from respondents at various times during the life history/intensive interview. Scenario questions provided the respondents’ gangs’ two major illegal activities (Page 1990). This scenario included specifics on the activity such as the individual in charge, the subject’s participation and the distribution of profits. Additionally, a closed-ended question elicited data on the gangs’ frequency of dealing during the last year. Individual level data was also collected by asking respondents their frequency of drug selling during the last year as well as the characteristics of their customers. The field note and life history /intensive interview data were combined into an electronic qualitative database. The data was then analyzed and contextualized for themes and commonalities. After the analysis of the data, we developed a typology based on distinct themes.

Dimensions of Drug Selling Behaviors and Drug Dealing Among Gang Members

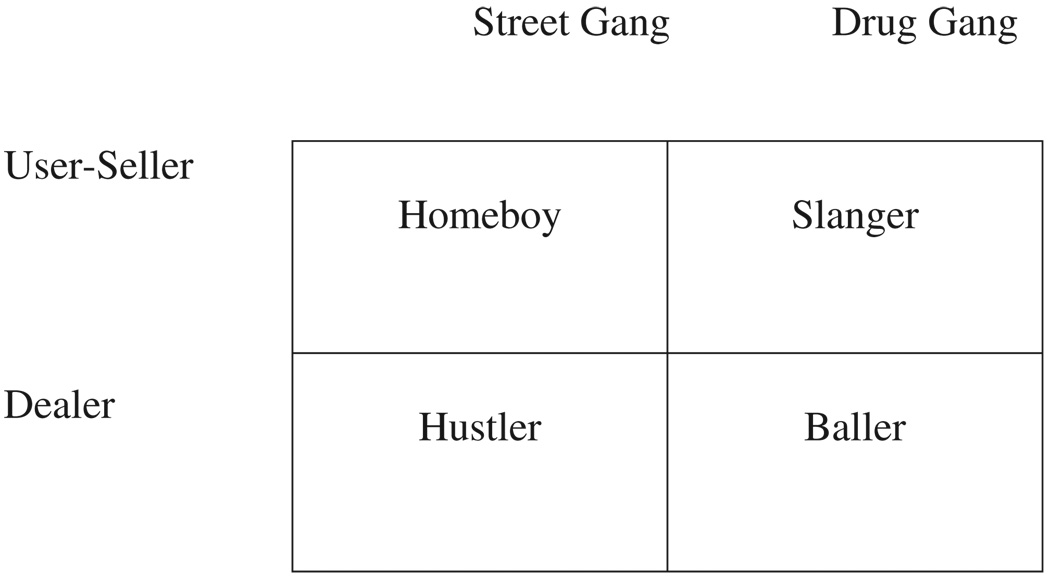

Based on the analysis of our qualitative data gathered during field observations and life history interviews, two dimensions have emerged (see Figure 1) that shape and influence behavior associated with drug use and dealing among gang members. These are dimensions, not absolute points, and there is room for overlap between categories (Bailey 1994).

Figure 1.

A Typology of Drug Dealers and User-Sellers in Street and Drug Gangs

The first dimension focuses on to what extent the gang as an organization is a drug dealing criminal enterprise. At one extreme are gangs who are not involved as a gang in drug dealing activity. These street gangs are traditional, territory-based gangs located in diverse neighborhoods ranging from public housing projects to single-family residential neighborhoods. Nineteen of the 26 gangs in this study were identified as street gangs. They encompass the various types of youth gangs described in the literature, but exclude criminal gangs which overlap with our drug gang category (Morales 2001). Street gangs generally are not hierarchical, although they adhere to some gang rituals such as identification with distinct colors, hand signs, and gang “placas” or symbols. They are involved in “cafeteria-style” crimes including auto theft, burglary, robbery, vandalism, criminal mischief, and petty crime. These crimes tend to be more individual and less organized. The gang member demonstrates more individual agency in his own activities and behavior. Violent behavior tends to be more random and personal rather than purposeful. The gang does offer protection from rival gangs or others in the community who threaten them. This protection is extended to those members who are involved in drug selling and dealing activities.

At the other end of this dimension are those gangs that are organized, criminal, drug dealing enterprises. These drug gangs, that comprised 7 out of the 26 gangs, usually function as a hierarchy with a clearly defined leadership that shares in the profits generated among all gang members involved in the business. Klein (1995:130) suggests these gangs exist in communities where there are “an adequate market of users, a sufficiently uncontrolled neighborhood, and connections with at least mid-level distributors.” They may consist of several independent cliques that function under the protective umbrella of a gang. These gangs are distinct from other gangs in that they are not concerned with territorial issues or “turf violations,” and do not engage in random acts of violence such as drive-by shootings. Violence among these gangs tends to be more systemic, i.e. related to drug distribution (Goldstein 1985). For instance, little importance is placed on identifying their territory with gang tags, even when other gangs tag their neighborhoods. Members are discouraged from engaging in more expressive acts of violence such as drive-by shootings, random assaults, and personal fights. According to several members, these types of violent acts draw unnecessary attention from the police, which could lead to exposure of covert drug dealing operations. Not all members of these gangs are involved in dealing drugs, some may be involved in other criminal enterprises such as auto theft and fencing stolen goods. Others, especially the younger members, may simply be involved in the gang “socially” without engaging in any criminal activity except occasional fights with rival gang members.

The second dimension identified by our analysis is based on an individual gang member’s role in selling and dealing drugs within the gang. The one extreme of this dimension is the user-seller who is primarily buying drugs for personal consumption, and selling a portion of the drugs to offset the costs associated with his drug use. This behavior tends to occur among users who are in the early stages of drug using careers or who have established a relatively controlled regular (daily or weekly) drug use pattern. A user-seller is typically a young gang member who smokes marijuana on a daily basis with friends and acquaintances in the context of socializing. Marijuana purchased by these types of members is usually a quarter ounce that sells for $20 to $30 in a typical barrio neighborhood. An average daily user may purchase a quarter ounce every 3 to 4 days. This does not necessarily mean that the person is smoking the entire quarter ounce himself, since marijuana is a drug that is generally shared with other users. Any profits generated by such a transaction are usually in the form of the drug involved. This pattern of marijuana use and purchasing behavior is common among most gang members in this community.

The other extreme of this dimension includes the dealers, gang members who deal drugs (marijuana, cocaine, and heroin) for their own profit. These persons are connected with criminal networks that provide easy or reliable access to the drug market. They are either dealing as an individual, or with a group of other gang members, or with individuals outside the gang. Profits generated by dealers vary from a highly lucrative business that may afford a newer model car, jewelry, stereo, and other accruements of wealth in the barrio, to barely enough money to sustain or distinguish the person from other nondealing “homeboys.” Drug use among these members varies from not using any drugs at all to those that have become heavy users of cocaine and heroin. The crossclassification of the subjects by the two dimensions result in a two-fold typology (see Figure 1).

Homeboys: Drug User/Sellers in Nondealing Gangs

Homeboys are gang members who belong to a street gang whose criminal behavior tends to be more individual, less organized, and less gang directed. Violent behavior tends to be more random and personal as opposed to more purposeful such as physically injuring someone because of an unpaid debt. Except for gang turf disputes, most violence is centered on interpersonal fights and random situational acts of violence often associated with male bravado. Most of these user-sellers usually buy just what they are going to use to get “high” and sell small remaining quantities to reduce the costs associated with their own consumption. Drug selling behaviors exhibited by these homeboys are essentially independent and separate from any formal link to a collective gang activity. These members usually “score” small amounts for themselves, friends and other associates. They may act as a middleman for members who may not have access to a connection. But, the primary feature of this user is that his drug selling is motivated more by the desire for pharmacological effects of a drug than desire to make a profit. One heroin sniffer stated, “Yeah, I am selling drugs, but only so I can get my own stuff. The gang don’t have shit to do with this.”

The Circle is a gang whose members exemplify this individualized selling/buying activity.2 Members of the Circle are like many of the other gang members in this study, they smoked marijuana on a daily basis and stayed high most of the day. Most gang members in the Circle, like other members in this category, tend to sell small amounts of marijuana. They would usually sell marijuana to other gang members, friends and acquaintances in the neighborhood. The quantity they sold was usually $10 bags. They would also occasionally sell cocaine in a similar fashion in $10 and $20 units.

A gang member commenting on selling and dealing in his gang said, “None of them deal, they mostly just buy it and smoke it or sniff it or whatever.” Even though the gang is not a drug dealing gang, in most cases, there is usually a “veterano” who is the source for the user/seller gang members. Veterano literally translates to veteran in English, and in Chicano street jargon is reserved for an older experienced criminal drug user. The primary source for the Circle was “Fat Boy” an older gang member who was marginally affiliated with the gang. He was linked through relatives to one of the prison gangs in the area who had connections to higher level dealers. Fat Boy operated with full knowledge of the gang leadership that consisted of a leader and two seconds. The leadership themselves had neither interest in dealing nor the profits generated by Fat Boy. The Circle was territorial, and involved in activities associated with protecting their turf, while drug dealing was not a primary interest.

The majority of the gang members buying from Fat Boy were relatively young, averaging from 15 to 18 years old, and had few dependable drug connections. As some of Fat Boy’s customers got a little wiser they started to develop their own connections outside the gang. For instance, Julio was sent to an alternative school after being expelled from his high school. At the alternative school he met someone who introduced him to a cocaine connection. Julio eventually began to use this connection rather than Fat Boy.

Another nondealing gang is the Invaders. This gang is located in a low-income, residential area characterized by modest and older single-family homes. The neighborhood is accessible by car only through a couple of major streets, making it difficult for rival gang members or anyone else to enter the area unobtrusively. The gang consists of approximately twenty members ranging in age from 14 to 18. Their primary illegal activity is “gang banging.” This includes protecting the gang’s turf from rival gangs, drive-by shootings, fights and assaults. The Invaders also have a reputation as a party gang known for heavy use of marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. The members seem to fall in the user/seller category with the majority involved in small-time drug selling, primarily marijuana sales.

Up in the Sky (UIS) is a gang that in the initial months of the research project had been classified as a “tagging crew.” This is a group of individuals whose major activity focuses on spray-painting walls, alleyways, street signs, and buildings in a highly individualistic style described as “graffiti art.” The general public, and school and police authorities often confuse tagging crew art for gang graffiti. In fact, tagging crew art is much more elaborate than gang graffiti, which is primarily used to mark off territory. These tagging crews are often in competition with each other for the most elaborate tags and the best location. Prestige is bestowed on those that display their art in the highest places (i.e., tops of buildings, freeway crossings).

Members of tagging crews vary according to the roles played in the organization’s tagging functions such as “bombers” and “crew members.” Bombers are members who actually create the works identified as graffiti art, while the crew provide support as assistants or lookouts. There are also members who are the “partyers.” They are attracted to the gang because of the group’s social activities, which include the frequent use of marijuana and alcohol, and the occasional use of cocaine. The leader of the UIS was a charismatic 19-year-old whose father was a police officer. In an interview, the leader stated, “In the beginning we didn’t let in anyone into the gang that was-n’t a tagger. But, as we started to get shit from other gangs we let them in.” These nontaggers were attracted to the gang because of the party aspect of the group, but did have to meet gang obligations like fighting rivals.

The members of this gang were primarily homeboys. A few of the gang members, including the leader, had a connection with an older acquaintance from whom he bought 1/2 to 1 ounce of marijuana at a time. He would resell the drug to the other members at a slightly higher cost than he purchased it to cover the cost of the marijuana he used. Other members of this crew were involved in a similar practice. According to the leader, “No one was making any money off the stuff.” However, as tension mounted between UIS members and other rivals they began to organize themselves more as a gang. As the crew began to diversify, the group’s activities expanded to more profit-oriented drug dealing by certain homeboys. The crew’s identity as a gang was solidified when they successfully defended themselves in a gang fight with one of the most notorious gangs in the area.

Hustler: Drug Dealers in Nondealing Gangs

Gang members identified as hustlers deal drugs for profit within a street gang that is not characterized as a drug dealing organization. However, it does provide protection to hustlers within the territory controlled by the gang. Protection is extended to those persons because they are members of the organization rather than because of their drug selling activities. Profits generated by these hustlers are their own and are not used to support the collective activities of the street gang.

The Chicano Dudes are one of the largest and most violent street gangs on the city’s West Side. There were approximately 59 members in the gang at the time of the study. Its territory is one of the largest public housing projects in the Mexican American community. The neighborhoods they dominate are filled with the gang’s tags on building walls, commercial billboards, and traffic signs.

The leader of the Chicano Dudes is Mark Sanchez who took over the gang after the previous leader was sent to prison for attempted murder. Most of the gang’s drug selling is controlled by Mark as an individual, not as leader of the gang. The dealers do not, and are not expected to share profits with the gang. The gang serves a lucrative drug market within a geographic territory they control, although Mark, “his boys” and the other hustlers sell outside this territory. It is the public housing territory, however, that the gang protects through intimidation and violence. Members are expected to support and defend the gang’s collective interests, often through violence, and may be required to participate in a drive-by shooting, an assault, or a gang fight. Violating this expectation could have serious repercussions, as one field worker’s notes recount:

Last night Jesse, an ex–Chicano Dude who turned Vida (an adult prison gang) got an order to jump on a Chicano Dude who broke a car window of a sister who is still a Chicano Dude, with him. He did his job, and roughed up Tony, the one who broke the window. The Chicano Dude who went along, Robert, did not do anything but observe the situation. This all happened around 9:00 p.m. till 11:00 p.m. Mark the head of Chicano Dudes sent a group of seven boys to find Jesse, and beat him. They also found Robert, and beat him for watching.

Mark Sanchez maintained the loyalty of a close-knit group of gang members who were primarily older gang members (OGs). Some of these members were involved in his drug dealing and others were not. They were used by Mark as his “backup” (protection) to deal with clients who were giving him trouble or not paying their drug debts. This selective group was given special treatment by Mark such as being provided a lawyer and bond if arrested. If members were incarcerated, he was also known to provide protection while “locked up."

As Mark’s drug dealing operation expanded, he began to sell drugs to other gangs on the West Side of San Antonio. When asked if this conflicted with his obligations as leader of the Chicano Dudes, one community researcher stated, “No, the dealing was seen as separate from the gang’s business such as protecting its turf. But, Mark would use gang members to back up his business.” Toward the end of the study Mark’s dealing operations were even expanding outside the gang community into other criminal social networks that put him in conflict with one of the adult prison gangs.

There were other members of the gang selling and dealing drugs that were not part of Mark’s clique and operated independently. One of these was a young charismatic gang member named Sparks who was the leader of a set within the Dudes comprised of the gang’s pee wees. “I really love these little guys, and try to take care of them,” he commented to us in an interview conducted by one of the authors of this paper. “I try and make sure they don’t get into too much trouble, especially staying away from the ‘brown’ (heroin).” Over the years of the study, as the Dudes evolved into primarily a drug dealing gang under the tyrannical control of Mark, Sparks stayed loyal to the principles of the gang. However, Sparks was dealing marijuana, cocaine and heroin to other gang members and people outside the gang. With profits from these deals he was able to purchase marijuana for his own use (which he smoked on daily basis) and support himself economically.

“Biggie” was another member of the Chicano Dudes who was dealing independently. He was the leader of set or clique within the gang located in a different section of the “courts” (public housing projects) they controlled. According to our fieldworkers, he sold ounces of cocaine and heroin. What made Biggie different from the other hustlers is that used his leadership of a major sub-set of the Chicano Dudes as front for his drug business. “He would even give out gang v’s (violations) for late payments and members who were getting addicted to heroin.” According to several sources, other gang members loyal to Biggie fatally beat one of Biggie’s crew for a violation. Biggie was given the leeway in these matters by Mark, as long as he remained loyal to him.

One of the distinctions of the Chicano Dudes was its independence from Vida Loca, an adult prison gang that operated in the same area as his gang. Over the years the prison gang had attempted to control the Chicano Dudes, particularly its drug trade. Mark Sanchez was one of the few gang leaders to stand up to them. He did this through his own violent behavior and the loyalty of several OGs who were not intimidated by these adults. Only recently did this independence begin to weaken when a rival gang associated with Vida Loca seriously injured Sanchez in an aborted attempt on his life. His vulnerability to the prison gang and personal accumulation of wealth started to affect the loyalty of many of his members to the gang and his leadership. Over the course of this study, this gang became to transform itself more into a dealing gang as its dealing activities became its primary activity.

Slanger: Drug User/Sellers in Drug-Dealing Gangs

Gang members in this category are characterized as user/sellers in gangs that are organized as drug dealing enterprises. Slangers are members who either chose not to participate in the higher levels of the gang’s organized drug dealing activities or who are excluded from those circles for various reasons. However, the slangers continue to use and sell drugs at an individual level mostly to help off-set costs associated with their drug use and to support themselves economically. In the vernacular of the gangs, these members are dealing to “get high and get by.” The slangers stand in contrast to the hardcore dealer members in the drug gang who are heavily involved in the gang’s higher level organized drug distribution activities.

Varrio La Paloma (VLP) is a gang that is located in San Miguel Public Housing Project, one of the oldest courts on the Westside. The gang’s activities have recently expanded to a working-class suburban subdivision outside the barrio after public housing authorities displaced many project families to this location. There are approximately 100 hard-core and 80 marginal members in this gang. Organizationally, this dealing gang has several sets or subgroups of members. Each of the sets has a head that is under the command of a leader. VLP is an older established gang and one of the few gangs whose former members were parents and other relatives who have in the past participated in this same gang.

The distribution of drugs by the VLP was controlled by the leader of the gang and his closest gang associates, primarily older hard core members, including two of his brothers. There were several cliques of members who were responsible for different tasks or functions associated with the gang’s drug business. VLP leadership had connections to wholesale drug distributors who were associated with independent adult criminals with ties to Mexico. The actual drug distribution in the barrios was conducted by slangers. The slangers were “fronted” drugs by the gang’s leadership for retail sale. Fronting is a form of credit or consignment in the drug culture given to sellers who agree to pay for the drugs within an agreed upon time. Amount of profits accrued by the slangers depends on their mode of distribution. One report from the field stated,

How much money a slanger made, depended on how you cut it, or whether you resold it in smaller qualities. If one of the guy’s in the crew got an eight ball (3½ grams) of cocaine from Leo for $100, he might mix it with a gram of cut for about a $50 profit if he sold the whole amount. Or, he could make more profits if he bagged it up in smaller quantities and sold it that way like 10s and 20s bags (dollars).

Selling in smaller units entails higher risks because of the higher volume of customers needed to get rid of the “batch.”

Interestingly, the VLP’s status as a drug dealing gang is a relatively recent phenomena and is in response to the emergence of the prison gangs in the community during the last 10 years. They became involved in a serious conflict with the adult prison gang, which was attempting to enforce its diez porciento (10%) take from VLP’s total sales. At that time, drug dealing was conducted on an individual basis by gang members. In order to protect their share of the drug market, the gang’s dealers began to organize their drug business around the gang. This allowed them to use the gang’s organization to protect themselves from the prison gang attempting to control the drug market in their community.

This conflict culminated when two adult prison gang members were murdered by a VLP member when he refused to cooperate with him. One of our fieldworkers described the time he met the VLP member soon after the shootout incident:

Georgie walked with the help of two crutches as he approached the car. Vida put out a contract on him because he refused to pay the 10% commission on his drug sales. Georgie had started out selling dime bags of heroin. Shortly thereafter, he was selling three to four ounces of heroin and coke a week. That’s when Vida started asking for their 10%. He said, “They sent two hit men. The men shot first hitting me in the thigh and the knee. I was shooting on the way down and killed them both. I gave the gun to Ray-Ray, who stashed it before the police got there.” Georgie was upset because none of the VLP got down for him.

Eventually, after serious threats of retaliation from both sides, the VLP and the prison gang reached a compromise. The VLP would be allowed to sell cocaine and marijuana, but the heroin trade would be the exclusive right of the prison gang even within the San Miguel Courts.

As previously mentioned, slangers are those members on the lower end of the gang’s dealing hierarchy. Slangers may include many of the younger members who were excluded from more serious drug dealing operations because of the legal risks and violence associated with these activities. This protective attitude was even stronger if the younger member was a sibling of the older veteranos drug dealers. One of these types told us, “There was no way my carnalito (younger brother) was going to get involved.” However, these members continued to engage in user-seller behavior to economically supplement their recreational drug use. What distinguishes these slangers from other user-sellers is the high-level protection and reputation of the drug gang. In fact, outsiders often treated them as full-fledged “ballers” (described in the following section) because of their drug dealing gang affiliation.

Another category of slangers in the VLP were gang members who voluntarily decided not to participate in the gang dealing activities, although to continue user/seller behavior. These often included VLP members on probation and parole. In these types of cases, the person fears that an arrest for drug dealing could result in a long prison term. This threat is often a deterrent to becoming involved in the gang’s organized drug dealing. In other cases, the veterano may be experiencing a process of maturing out of the gang life style. In these situations the member is often emotionally attached to a woman whose child he may have fathered. He may have also found a job that offered a good salary and some stability. At this point in his life, the veterano may be considering dropping out of the gang scene. However, he may still be using drugs, especially marijuana, and since he has solid connections to drug dealers, he will continue to sell to a few trusted customers to compensate for his own drug use. As one of these slangers put it, “I am selling enough to cover my own huesos (bones).”

Ballers: Drug Dealers—Drug-Dealing Gangs

As discussed, drug gangs are those organized as a criminal enterprise with profits distributed either to the gang as an entity or equally among the gang members active in the organization. Ballers are the individuals within these gangs who control the drug distribution business. One gang member commented, “These are the batos (guys) making all the feria (money), jewelry, and fancy cars. They have the big connections.” The ballers usually sit atop the gang’s hierarchy and comprise a leadership structure that provides protection to members against rival gangs and predatory adult criminals. Among these gang members, heroin use was generally discouraged, although as the gangs began to deal heroin, many ballers began shabanging (noninjection) and/or picando (injecting), and some subsequently became addicted. One of the distinctions of ballers from seller-dealers, slangers and homeboys is their generally lower visibility and the higher volume of drugs they deal. “You don’t see these guys on the street selling drugs like those others,” an older gangster (OG) member mentioned to us in an interview. Furthermore, they avoid ostentatious aggressive behavior that attracts law enforcement like drive-by shootings. Violence among ballers is also more purposeful and revolved around business transactions as discussed in Goldstein’s drug-nexus typology (1985).

The Nine-Ball Crew (NBC) is a dealing gang located in La Luna Courts, another large city housing project. This gang was distinct from other youth gangs in its direct ties to Vida Loca. This prison gang controlled the heroin trade in this community by imposing the 10 percent rule that it enforced through violence and intimidation. The gang leader’s stepfather was one of the heads of the prison gang. Over the last few years, they have recruited several gangs, and subsequently their members, to distribute heroin for them. Although, the relationship between a youth gang and the adult prison gang is initially based on drug distribution, the youth gang often becomes a subsidiary of the prison gang. The control of Vida Loca over the NBCs is their most successful example of this process. During the course of the study, a Nine-Baller shot the leader of the Chicano Dudes for refusing to pay the adult prison gang a percentage of his profit. The hit was an attempt by the adult prison gang to solidify their control of the drug trade in this area.

The Nine-Ball Crew is highly organized with a leader and two second-heads or lieutenants, a hard-core membership of 20 members and approximately 30 others. The leader of this gang is Juan, a baller, who tightly rules the gang. He is 23 years old and has been described as “cold-blooded and vicious.” His control of the gang is solidified by the support of his five brothers who are active in the gang. The NBC drug market is primarily in the La Luna Courts and nearby vicinity, where there is little competition from other sellers and dealers. The selling of drugs is coordinated by one of Juan’s brothers and another member identified as an original gangster (OG). The gang’s hardcore membership, under the direct supervision of the two heads, is responsible for the distribution and sale of the drugs. Ballers, such as Juan and his OGs, are the primary sources of drugs for other slangers, hustlers, homeboys, and other drug sellers in the community. When one of the NBC members was asked about Juan, he said

Yeah, he’s the main guy that controls the drugs. He says who is going to sell and who ain’t going to sell. If you’re selling without permission and don’t bring money to him you’re going to get in trouble, get a v.

Another well recognized baller was Pio Gomez who operated out of a public-housing complex on the near West Side. What distinguished him from some of the other ballers was that he was not a member of one of the drug gangs. He was actually a childhood friend of a leader of the Chicano Dudes. This widely acknowledged relationship among gangs members and the community allowed him to run his drug business as if he was a high-ranking member of a drug gang. This provided him the “street muscle” to deal with those who tried to interfere in his business or refused to pay their debts to him and his crew. Through independent adult dealers and other dealing gangs, including Mark from the Chicano Dudes, he would acquire kilos of cocaine and ounces of heroin. Pio broke these larger quantities into ounces, half ounces, quarter ounces and eight-balls (3 1/2 grams) that he fronted to his crew. His crew, which consisted of gang members and other young men, distributed the drugs to slangers in the courts and the surrounding neighborhoods. Over the course of the study, Pio generated a great deal of money, spending it in a very conspicuous manner. One gang member stated, “Everyone considered Pio a baller. He bought a brand new silver Eclipse. He had gold chains, expensive watches that stood out like a sore thumb. But, he never got busted. Some of his crew did, but not him."

During the period of this study there were gang members who moved from one category of the typology to another. El Gato, the leader of the Deep West, transformed himself from a slanger to baller, and finally was recruited as a “soldier” by Vida Loca. El Gato used his gang members as runners in an area on the western outskirts of the Mexican American community. At the height of his dealing career, he was distributing large amounts of cocaine and heroin. When El Gato was finally arrested, it was for possession with intent to distribute 6 ounces of cocaine and 4 ounces of heroin, an amount he would sell through his crew 2 or 3 times a week. Most of these drugs were fronted to other gang members or other independent drug sellers. To make sure that his gang members stayed loyal and in his services, he was known for giving away $10 to $20 bags of heroin to them. As result, many of his hard-core slangers became addicted and were less useful to his operation especially in collection efforts. As El Gato started to lose key members to heroin addiction and increased police pressure, he started to create alliances with the prison gang that eventually recruited him as a full-fledged member.

Although many of the dealing gangs, and subsequently the ballers were generating large amounts of money, others were not. One informant told us, “the VLP as a gang wasn’t selling nothing compared to a couple of guys (a set) associated with the Chicano Dudes.” He went on to explain how the VLP were really small-time in the larger drug market in the community, although, the VLP did manage to control through violence a corner of that market in the courts. “These guys were not driving around in new cars, and flashing money around. These guys were small time, many couldn’t even pay their utility bills.” However, even those ballers and hustlers like Mark Sanchez that were perceived as “ making money” were not wealthy enough to invest in legitimate businesses like more successful criminals such as those in larger illegitimate enterprises.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

We have attempted to develop a framework for describing and understanding the relationships among drug use, gang membership, and drug distribution and gang membership in the context of a Mexican American community in South Texas. We constructed this framework along two dimensions: (1) the gang’s organizational structure defined by involvement in drug dealing; and (2) the individual gang member’s role in using, selling and dealing drugs. The analysis of the two dimensions resulted in a fourfold typology. The typology encompasses a wide range of connections and intersections between gangs, their individual members, and the selling of illegal drugs within the wider distribution system.

Malcolm Klein (1995:132) asserts that a clear distinction exists between street and drug gangs (Howell and Gleason 1999). He posits that few gangs are involved as an organization in drug distribution in entrepreneurial marketing of drugs because of key structural limitations. For example, drug dealing requires a hierarchical and cohesive organization, dependable leadership, a business focus, and avoidance of opportunistic “cafeteria style” crimes. Our findings generally corroborate Klein’s theory as applied to the Mexican Americans in South Texas. However, our data suggests that Klein underestimates the extent to which street gangs and gang members are fluid in their drug dealing roles and are susceptible to existing, adult based drug distribution systems.

Findings from this study suggest that gang members’ involvement in selling and dealing is influenced by the presence of adult criminals in key members’ social network. Many of the gang members are related by family ties to adult criminals who are prison gang members active in drug distribution. Moore (1994) similarly described the importance of the “cholo” family in sustaining a wide array of delinquent and criminal behavior among Mexican Americans in Los Angeles (Vigil 1988 andMoore 1994). This “intergenerational closure” provides a social cohesiveness to the street gang that sharply contrasts to that in Chicago that has been related to positive social outcomes (Sampson, Morenoff, and Earls 1999). Nonetheless, the capacity of adult criminal family relationships to influence and intervene in the lives of young males provides a marker for distinguishing the Mexican American gangs in this study.

The inclusion of the second dimension pertaining to drug user-seller and dealer roles in the construction of our typology provides a more comprehensive understanding of gangs and the drug distribution system. The appreciation of the subtle yet complex roles played by individual gang members in this system has been overlooked by some gang researchers. An exception has been the work of Spergel (1995) who recognized a fluidity and similarity in the roles of members in street and drug gangs. Our typology contributes to this recognition by explicating the multiplicity of roles that individual gang members play in the drug distribution system that is not necessarily dictated by gang structure, i.e. street vs. drug gang.

The role of gang members in this system is often obscured because of the fact that most gang members are more frequent users and sellers of drugs compared to other non-gang youth. But as Spergel (1995) concludes, this does not mean that the majority of gang members are dealers as we have defined them by our typology nor that the gangs they belong to are necessarily criminal drug organizations. What emerges from our data is that some gangs have nothing to do with the dealing of drugs. This was clearly illustrated by the “tagging crew” who spent their time, energy and money on elaborate, although illegal, displays of public art, and not the selling of illegal drugs.

Another important finding of this study is that drug selling and dealing is not only related to extended family networks but also to the larger social context of the gang. Thus, the gang can offer to drug sellers and dealers protection in exchange for their commitment and obligation to the gang. As a result, the role of the gang in the distribution of drugs in the community is difficult to discern and is obscured to most outsiders. For instance, protection may often misperceived by police as evidence that a gang is a drug dealing enterprise when in reality members may be operating independently from the gang. Often law enforcement personnel indiscriminately extend this flawed perception to all Mexican American youth living in these neighborhoods. This misconception may lead to continual harassment, shakedowns and detainment of many innocent youth.

A serious consequence of this perception is very often drug law enforcement that indiscriminately arrests and prosecutes offenders without distinguishing the differences that constitute our four distinct types. Even those “homeboys” arrested for minor violations of drug laws, such as possession of small amounts of marijuana, get caught up in a criminal justice system that often treat them like “ballers,” leading to serious lifelong consequences. Our typology suggests that a more variegated law enforcement and balanced social intervention policy is needed to address the complexity of the situation.

The analysis presented here suggests the need for police, judges and district attorneys to understand the relationship between the use of illegal drugs by poor youth and the diverse operative roles these youth may play in the distribution of these drugs. Police need to be trained in recognizing the differences in the “homeboy” user/seller who is affiliated with a street gang from “slangers” and “ballers” who are the persons really dealing drugs. Judges also need more discretion in the sentencing of those who violate drug laws. Mandatory sentencing minimums need to be balanced with social work and treatment options for “homeboys,” and in certain cases “hustlers” and “slangers.” These changes in policy would shift the emphasis away from a wholesale punishment approach, usually in the form of incarceration, to a refined rehabilitation approach involving creative applications of drug treatment, job training, and probationary social work.

In closing, the methodological limitations of our study need to be acknowledged. Common with other ethnographic and qualitative studies, the generalizability of the results is limited to other communities. Ethnographic studies of drug dealing often arrive at seemingly contradictory findings in relatively similar communities (Hagedorn 1988; Taylor 1990). South Texas, with its proximity to Mexican trafficking operations, may present so special a context that replication of our gang drug dealing typology without essential modifications would be problematic. However, confidence in the generalizability of our typology is increased in that we were able to find and distinguish street and drug gangs and membership behavior in South Texas as has been widely done elsewhere. This is complemented by the inclusion in our analysis of the mechanism of intergenerational closure to help explain the variation we discovered. A deeper and more extended program of qualitative research needs to be initiated in cities in diverse regions and with gang members of other ethnicities in order to further evaluate the significance of the findings from this single study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Charles D. Kaplan, Joan Moore, and David Desmond for consultation and comments; Richard Arcos, Ramon Vasquez, and Alice Cepeda for research assistance. This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01 DA086.

Biographies

Avelardo Valdez is currently a professor at the University of Houston, Graduate School of Social Work and director of the Office for Drug and Social Policy Research. He has been a recipient of several federally funded research projects on Mexican American drug use, violence, and gangs. His more recent publications include research on street gangs, female drug users, and sex workers on the U.S./Mexico border. He is currently a principal investigator on a National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) grant that focuses on Mexican American noninjecting heroin use.

Stephen J. Sifaneck, Ph.D., is presently a project director/coinvestigator in the Institute for Special Populations Research (IPSR) at National Development and Research Institutes (NDRI) Inc. in New York City. His publications include articles and chapters about the sale and use of marijuana, heroin and prescription drugs, ethnographic research methodologies, and subcultural urban issues.

Footnotes

In the literature there are very different definitions of what constitutes an adolescent gang (Klein 1971; Miller 1975; Moore 1978; Yablonsky 1962) often based on the researcher’s relationship to the gang and source of information. The definition used in study is based on our experiences in working with gangs in San Antonio.

All the names of gangs and gang members are aliases. Some of the descriptive characteristics have been altered to prevent identification of the actual participants, gangs, and neighborhoods.

Shabanging is a term used by these youth to describe intranasal use of heroin, typically via a plastic nasal spray bottle. The heroin is diluted with water and sprayed into the nasal cavity with the plastic device.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler Patricia A. Wheeling and Dealing: An Ethnography of an Upper-Level Drug Dealing and Smuggling Community. New York: Columbia University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade Xavier, Sifaneck Stephen J, Neaigus Alan. Dope Sniffers in New York City: An Ethnography of Heroin Markets and Patterns of Use. Journal of Drug Issues. 1999;29:271–298. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey Kenneth B. Typologies and Taxonomies: An Introduction to Classification Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bullington Bruce. Heroin Use in the Barrio. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chin Ko-Lin. Chinese gangs and extortion. In: Klein MW, Maxson CL, Miller J, editors. The Modern Gang Reader. Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury; 1995. pp. 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornyn John. Austin, TX: Office of the Attorney General, State of Texas; 1999. [Retrieved August 15, 2003]. Gangs in Texas: 1999. from http://www.oag.state.tx.us/AG_Publications/pdfs/1999gangs.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Covey Herbert C, Menard Scott, Franzese Robert J. Juvenile Gangs. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Decker Scott, Van Winkle Barrik. Slinging Dope: The Role of Gangs and Gang Members in Drug Sales. Justice Quarterly. 1996;11:583–604. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolan Edward F, Finney Shan. Youth Gangs. New York: Julian Messner; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagan Jeffery. Gangs, Drugs, and Neighborhood Change. In: Huff CR, editor. Gangs in America. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1996. pp. 39–74. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furst Terry R, Curtis Richard S, Johnson Bruce D, Goldsmith Douglas S. The Rise of the Street Middleman/Woman in a Declining Drug Market. Addiction Research. 1997;5:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein Paul J. The Drugs/Violence Nexus: A Tripartite Conceptual Framework. Journal of Drug Issues. 1985;15:493–506. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagedorn John. People and Folks: Gangs, Crime and the Underclass in a Rust Belt City. Chicago: Lake View Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagedorn John. Neighborhoods, Markets, and Gang Drug Organization. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1994a;31:264–294. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagedorn John. Homeboys, Dope Fiends, Legits, and New Jacks. Criminology. 1994b;32:197–219. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagedorn John, Torres Jose, Giglio Greg. Cocaine, Kicks, and Strain: Patterns of Substance Use in Milwaukee Gangs. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1998;25:113–145. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammersley Martyn, Atkinson Paul. Ethnography, Principles in Practice. London: Routledge; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howell James C, Gleason Debra K. Youth Gang Drug Trafficking. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunt Dana E. Drugs and Consensual Crimes: Drug Dealing and Prostitution. In: Tonry JQWAM, editor. Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research, vol. 13: Drugs and Crime. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 159–202. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunt Dana E, Lipton Douglas S, Spunt Barry. Patterns of Criminal Activity Among Methadone Clients and Current Narcotics Users Not in Treatment. Journal of Drug Issues. 1984;14:687–702. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs James B. Street Gangs Behind Bars. Social Problems. 1974;21:395–409. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jankowski MartínSánchez. Islands in the Street: Gangs and American Urban Society. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson Bruce D, Williams Terry, Dei Kojo A, Sanabria Harry. Drug Abuse in the Inner City: Impact on Hard-Drug Users and the Community. In: Tonry M, Morris N, Justice NIO, editors. Drugs and Crime. vol. 13. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasarda John D. Urban Underclass Database: An Overview and Machine-Readable File Documentation. New York: Social Science Research Council; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein Malcolm. Street Gangs and Street Workers. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein Malcolm. The American Street Gang. New York: Oxford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 27.LeCompte Margaret D, Schensul Jean J. Designing & Conducting Ethnographic Research, Ethnographer’s Toolkit. Vol. 1. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mieczkowski Thomas. Geeking Up and Throwing Down: Heroin Street Life in Detroit. Criminology. 1986;24:645–665. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller Walter B. Violence by Youth Gangs and Youth Groups As a Crime Problem in Major American Cities. Washington, DC: Department of Justice; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joan Moore. Homeboys: Gangs, Drugs, and Prison in the Barrios of Los Angeles. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore Joan. The Chola Life Course: Chicana Heroin Users and the Barrio Gang. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1994;29:1115–1126. doi: 10.3109/10826089409047932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morales Armando T. Urban and Suburban Gangs: The Psychosocial Crisis Spreads. In: Morales AT, Sheafor BW, editors. Social Work: A Profession of Many Faces. 9th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. pp. 397–433. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Office of National Drug Control Policy, High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas. Southwest Border HIDTA South Texas Partnership. [Retrieved August 15, 2003];2002 from http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/hidta/frames_stex.html.

- 34.Padilla Felix M. The Gang As an American Enterprise. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1992a. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Padilla Felix M. Becoming a Gang Member: The Gang As an American Enterprise. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1992b. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Page Bryan. Shooting Scenarios and Risk of HIV-1 Infection. The American Behavioral Scientist. 1990;33:478. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Preble Edward, Casey John J. Taking Care of Business—The Heroin User’s Life on the Street. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1969;4:1–24. doi: 10.3109/10826089709027307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sampson Robert J, Morenoff Jeffery D, Earls Felton. Beyond Social Capital: Saptial Daynamic of Collective Efficacy for Children. American Sociological Review. 1999;64:633–660. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanders William B. Gangbangs and Drive-by. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sifaneck Stephen J. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. New York: City University of New York (CUNY); 1996. Regulating Cannabis: An Ethnographic Analysis of the Sale and Use of Cannabis in New York City and Rotterdam. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sifaneck Stephen J, Neaigus Alan. The Ethnographic Accessing, Sampling and Screening of Hidden Populations: Heroin Sniffers in New York City. Addiction Research and Theory. 2001;9:519–543. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skolnick Jerome H, Correll Theodore, Navarro Elizabeth Navarro, Rabb Roger. The Social Structure of Street Drug Dealings. American Journal of Police. 1990;9:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spergel Irving A. The Youth Gang Problem: A Community Approach. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sullivan Mercer L. Getting Paid: Youth Crime and Work in the Inner City. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor Carl. Dangerous Society. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venkatesh Sudhir A. The Social Organization of a Street Gang Activity in an Urban Ghetto. American Journal of Sociology. 1997;103:82–111. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vigil Diego. Barrio gangs. Austin: University of Texas Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waldorf Dan. When the Crips Invaded San Francisco: Gang Migration- Homeboy Study. Alameda, CA: Institute for Scientific Analysis; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waldorf Dan, Lauderback David. Gang Drug Sales in San Francisco: Organized or Freelance? Alameda, CA: Institute for Scientific Analysis; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wiebel Wayne. The Indigenous Leader Outreach Model: Intervention Manual. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams Terry. The Cocaine Kids: The Inside Story of a Teenage Drug Ring. Redding, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yablonsky Lewis. The Violent Gang. New York: McMillan; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yin Zenong, Valdez Avelardo, Mata Alberto G, Jr, Kaplan Charles. Developing a Field-Intensive Methodology for Generating a Randomized Sample for Gang Research. Free Inquiry-Special Issue: Gang, Drugs and Violence. 1996;24:195–204. [Google Scholar]