Abstract

BACKGROUND

Routine opt-out provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling (PITC) remains underutilized in sub-Saharan Africa. By selectively targeting clients who either volunteer or have clinical indications of HIV disease, standard approaches to HIV counseling and testing are presumed more cost-efficient than PITC.

METHODS

1221 patients ages 15-49 were seen by 22 practitioners in a mobile clinic in southern Zambia. A random sample of physicians was assigned to administer PITC while the remaining practitioners offered standard non-PITC (i.e., voluntary or diagnostic) counseling and testing. Questionnaires assessed patient demographics and attitudes toward HIV. HIV detection rates were stratified by referral type, demographics, and HIV-related knowledge and attitudes.

RESULTS

HIV prevalence was 10.6%. Infection rates detected using PITC (11.1%; 95% CI 8.8% to 13.5%) and standard non-PITC (10.0%; 95% CI 7.5% to 12.5%) did not significantly differ (OR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.67 to 1.52, p = 0.95). Patients who did not request testing or demonstrate clinical indicators of HIV did not have significantly higher HIV prevalence than those who did (OR = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.55 to 1.24, p = 0.36). Implementation of PITC was highly acceptable and produced a three-fold increase in patients tested per practitioner compared to standard non-PITC (114 vs. 34 patients per practitioner respectively).

CONCLUSION

PITC detected a comparable HIV infection rate as a standard non-PITC approach among rural adults seeking primary care services. Widespread implementation of PITC may therefore lead to significantly more cases of HIV detected.

Keywords: HIV testing, HIV counseling and testing, screening, stigma, rural, Zambia

INTRODUCTION

Underutilization of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing services remains a principal obstacle to effective implementation of HIV prevention and treatment programs.1-5 Early HIV diagnosis facilitates timely access to care and antiretroviral therapy that can subsequently improve mortality outcomes and may reduce HIV transmission rates.1-3,6,7 In sub-Saharan Africa where the HIV burden is the world’s highest, as many as 80% of HIV-infected adults were estimated to be unaware of their serostatus in 2007.1,8 Additionally, a 2007 estimate suggested that 90% of the adult population has never received an HIV test, and only 2.2% of adults received such testing and counseling annually.1,8,9

Traditionally, standard HIV counseling and testing has been offered in two types of settings. The first is known as client-initiated, opt-in voluntary counseling and HIV testing (VCT). The second is diagnostic counseling and testing (DCT), initiated by healthcare providers for those clients who demonstrate signs or symptoms of HIV infection or have other identifiable risk factors for HIV infection. With increasing recognition of the limitations of these standard approaches, a third approach has evolved: routine, opt-out provider-initiated testing and counseling (PITC).2,10-13 For years opt-out antenatal HIV testing and counseling has successfully increased HIV testing as a standard part of prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) programs.11,14,15 Beginning May 2007, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) officially recommended that PITC be offered to “all adults and adolescents seen in all health facilities” in areas with an HIV prevalence greater than 1% and where appropriate prevention, treatment, and care resources are available.1

Despite a call for its expansion, PITC remains underutilized, in part due to increased requirements for test kit, laboratory, and human resources.16 An increase in total HIV cases detected in the general patient population using PITC would support its widespread adoption. However, because standard counseling and testing programs serve volunteering clients or those with identifiable risk factors, they are expected to detect a higher number of HIV cases per unit cost when compared to routine testing programs.17

Therefore, these additional costs associated with higher testing volume may be further justified if PITC programs are able to detect a proportionally equal or higher percentage of infected individuals than the standard approach. To our knowledge, no study to date has compared PITC HIV detection rates against standard non-PITC programs in a general patient population in rural sub-Saharan Africa. We conducted a randomized clinical trial among adults attending a mobile medical clinic in rural setting in southern Zambia to compare HIV detection rates by testing strategy and to assess attitudes toward PITC.

METHODS

Study Population

Between July 14, 2008 and July 22, 2008, we provided HIV counseling and testing services to 1221 adults ages 15-49 years who presented to a mobile clinic at any one of four rural sites in southern Zambia. The clinic was designed to provide acute medical, dental, optical, and wound care. At each site, patients with medical chief complaints were seen and treated on a first-come first-serve basis by one of 22 health service providers (10 physicians, 9 registered nurses, 2 clinical officers, 1 nurse practitioner) who were instructed at study outset to refer patients for on-site HIV counseling and testing by one of two different methods. The number of providers designated to each referral method was based on estimates of clinic laboratory and counseling capacity. Sixteen providers (4 physicians, 9 registered nurses, 2 clinical officers, 1 nurse practitioner) were trained to refer those patients who requested HIV testing or who demonstrated signs or symptoms of HIV/AIDS according to WHO staging criteria or exhibited other identifiable risk factors for HIV infection (standard non-PITC). The remaining 6 providers were randomly selected among the physicians to refer every patient for HIV counseling and testing, regardless of presenting condition or complaint (PITC). PITC providers were further asked to document any patient initiation or request for testing, as well as the presence of signs and symptoms that would have prompted referral under traditional circumstances, in the same fashion as the standard non-PITC group. All patients were repeatedly informed of the availability of on-site counseling and testing services in both English (the national language) and the local language, Tonga. Patients could request counseling and testing at any time during their visit (i.e., in registration, triage, exam room, or the pharmacy).

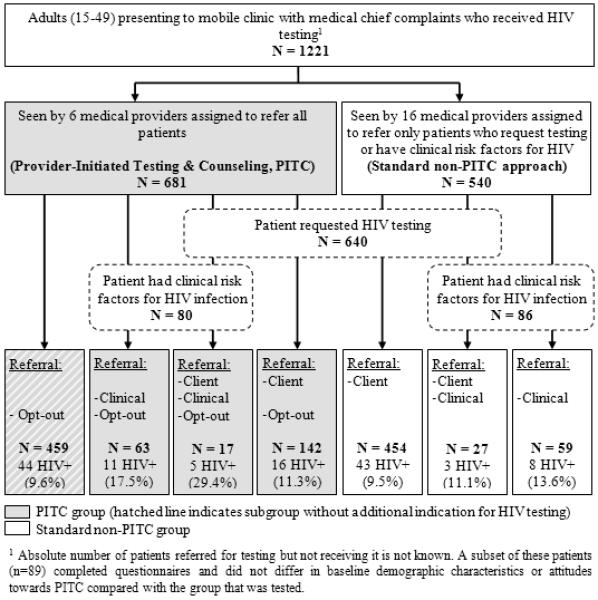

Patients, therefore, presented for HIV testing for three reasons: 1) Client request (standard counseling and testing); 2) Provider referral based on clinical presentation (also a standard form of counseling and testing); and 3) Routine, opt-out referral (PITC) (Figure 1). Occasionally, individual patients were referred through multiple pathways. Although patients presented to mobile clinics for different types of care (medical, dental, optical, wound) only patients seeking medical care were included, in order to improve the generalizability of our findings to a general adult patient population presenting for primary care in rural Zambia. The primary analysis was via intent-to-treat analysis with the PITC group including all patients referred by the routine, opt-out approach and the standard non-PITC group including all remaining patients referred either by client initiation or high-risk clinical presentation. Hereafter, we respectively refer to these two groups as the PITC and standard non-PITC groups.

Figure 1.

Patient referral characteristics in the provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling (PITC) group of providers and in the standard non-PITC group, rural Southern Province, Zambia, July 2008. Reasons for referral include client request (client), clinical risk factors (clinical), or routine, opt-out referral (opt-out).

Data Collection

After receiving medical care, patients with referral for HIV testing and counseling by either standard non-PITC or PITC were directed to a separate area designated for all clinic testing. Trained Zambian nurses fluent in English and Tonga provided pre- and post-test counseling according to WHO guidelines. Patients were tested for HIV infection using Determine HIV-1/2™ (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL), with confirmation of positives using Unigold HIV™ (Trinity Biotech, Bray, Ireland), in accordance with Ministry of Health guidelines. Guidelines have been validated locally via the dual rapid test algorithm and a quality-control procedure described elsewhere.18 Test results were linked confidentially to patient referral cards and stored securely by laboratory personnel. All patients testing positive for HIV received explicit referral to the nearest antiretroviral treatment site.

A separate group of clinic assistants, masked to patient HIV status, administered a brief socio-demographic questionnaire prior to pre-test counseling to a convenience sample of PITC and standard non-PITC patients. The questionnaire was developed from previously tested survey instruments,19,20 and was translated to Tonga and back-translated to English by independent professional translators. Bilingual interviewers used a standardized protocol to conduct the survey in either language as per patient preference. The structured interview collected demographic information on age, sex, occupation, education, income, relationship status, access to health care services, and prior HIV test history. Knowledge about and stigmatizing attitudes toward HIV testing were assessed as score-based variables using validated ten- and four-question survey tools respectively,19,20 with scores treated as binary for analysis. Similarly, the patient’s personal and perceived partner favorability toward routine, opt-out HIV testing were obtained using questions derived from previously tested instruments in which respondents selected from a range of disfavor to favor with results analyzed in a binary fashion.21

Statistical Methods

The study evaluated three primary outcomes stratified by testing referral method: 1) HIV serostatus; 2) history of prior HIV test; 3) attitude towards PITC. Univariate comparisons of patient characteristics by referral group, HIV status and patient favorability toward PITC were conducted using rank sum and chi-squared tests. We employed multivariable logistic regression models to assess the association between referral methods and HIV status. We adjusted for age, sex, and clinic site as potential predictors of HIV status. Age was a continuous predictor that was nonlinear with the log-odds of HIV positive status. To relax our linearity assumption, we modeled age using a restricted cubic spline with three knots. The objective of this study was to assess equivalence of HIV prevalence for two referral types, standard non-PITC and PITC. A retrospective power analysis indicated we had 80% power to detect a 50% difference in HIV detection rates between the two testing modalities.

Additionally, we sought to identify patient characteristics predictive of a history of HIV testing. We used multivariable logistic regression modeling, with age, sex, stigma towards HIV, knowledge of HIV, and education serving as predictors of testing history. Predictors were selected a priori. R-software 2.9.2 (available at: http://www.r-project.org, accessed February 22, 2010) was used for all data analyses.

Ethical Considerations

Both the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board and the Namwianga Mission, an institutional member of Churches Health Association of Zambia, reviewed the study protocol and provided ethical approval. Depending on literacy level, written or verbal consent was obtained from all participants.

RESULTS

A total of 1221 adults ages 15 to 49 who presented to our mobile clinic with medical complaints or requesting screening services received an HIV test. We selected 317 (26%) to complete study questionnaires based on interviewer and patient availability.

The PITC group consisted of 681 (56%) patients. Of these, only one-third (n=222; 33%) would have been referred for testing in the absence of a PITC approach, including 142 (64%) only via client request, 63 (28%) only via the provider’s clinical suspicion of HIV infection, and 17 (8%) via both. The standard non-PITC group consisted of 540 (44%) patients, including 454 (84%) referred for testing strictly by client request, 59 (11%) referred strictly by provider clinical suspicion of HIV infection, and 27 (5%) referred for both (Figure 1). Altogether, PITC tested 114 adults per practitioner, while standard non-PITC tested 34 adults per practitioner. PITC and standard non-PITC groups were similar in all baseline characteristics except for sex (proportionately more women in PITC vs. standard non-PITC groups, p < 0.01) and clinic location (p < 0.01) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Population characteristics in the Provider-Initiated Testing and Counseling (PITC) and standard non-PITC groups in rural southern Zambia, 2008

| Standard Non-PITC Group |

PITC Group |

Total | p-valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%), unless otherwise indicated | (n=540) | (n=681) | (n=1221) | |

| Female Sex | 323 (60%) | 552 (81%) | 875 (72%) | <0.01 |

| Age in years (IQR) | 28 (22, 38)a | 30 (23, 38) | 30 (22, 38) | 0.27 |

| Clinic Site | <0.01 | |||

| Kanchindu | 258 (48%) | 166 (24%) | 424 (35%) | |

| Mboole | 65 (12%) | 91 (13%) | 156 (13%) | |

| Simpweze | 116 (22%) | 304 (45%) | 420 (34%) | |

| Zyangale | 101 (19%) | 120 (18%) | 221 (18%) | |

| Education: None or some primaryb | 52 (37%) | 71 (44%) | 123 (41%) | 0.23 |

| Marital Status | 0.43 | |||

| Single | 20 (16%) | 18 (12%) | 38 (14%) | |

| Unmarried, in a relationship | 17 (13%) | 26 (18%) | 43 (16%) | |

| Married | 84 (66%) | 99 (67%) | 183 (67%) | |

| Widowed | 7 (5.5%) | 4 (3%) | 11 (4%) | |

| Number of wives | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 1.8) | 1 (1, 2) | 0.81 |

| Number of sexual partners | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | 0.72 |

| Travel time to nearest clinic (min) | 60 (30, 120) | 60 (43.8, 120) | 60 (30, 120) | 0.40 |

| Clinic visits in last 12 months, Noned | 35 (25%) | 34 (23%) | 69 (24%) | 0.82 |

| Never previously tested for HIVe | 62 (44%) | 79 (49%) | 141 (47%) | 0.44 |

| Time since last HIV test | 0.29 | |||

| < 12 months ago | 16 (30%) | 27 (43%) | 43 (37%) | |

| 12-24 months ago | 23 (43%) | 24 (38%) | 47 (40%) | |

| > 24 months ago | 15 (28%) | 12 (19%) | 27 (23%) | |

| Little or no knowledge of HIV and testingf | 55 (39%) | 54 (33%) | 109 (36%) | 0.33 |

| No Stigma towards PLWHAg | 63 (44%) | 72 (44%) | 135 (44%) | 0.99 |

| Personally Favorable toward PITCh | 100 (98%) | 108 (95%) | 208 (96%) | 0.36 |

| Partner seen as favorable toward PITCh | 98 (90%) | 106 (82%) | 204 (86%) | 0.13 |

Continuous variables are reported as medians (interquartile range).

Percentages are computed using the number of survey respondents with a non-missing value.

To compare the distribution of study characteristics by testing group, we employ chi-square tests. Similarly, we use a two-sample rank sum test for continuous variables by testing group.

p-value for No clinic visits vs. One or more clinic visits in past 12 months.

p-value for Never tested vs. previously tested for HIV.

p-value for No vs. Partial or full knowledge of HIV.

PLWHA means persons living with HIV or AIDS. p-value for No stigma vs. Partial or high stigma.

PITC means provider-initiated testing and counseling. p-value for Very or somewhat in favor of PITC vs. Very or somewhat opposed.

Most participants were female (72%) and married (66%). The mean age of the study population was 30 years [interquartile range (IQR) 22-38]. Among married males, 28% reported two or more wives. Among married females, 30% reported that their husbands had multiple wives. Only 59% of patients had a full primary education, and 76% reported at least one health clinic visit in the last 12 months.

Overall, 53% of patients reported a prior HIV test. Among those previously tested, 37% had been tested in the last 12 months, primarily through regional sites providing standard non-PITC services. When adjusted for other variables, being female (OR 2.4; 95% CI 1.1 to 4.0; p<0.001) and possessing fewer stigmatizing attitudes towards PLWHA (OR: 1.4; 95% CI 1.1 to 1.9; p=0.02) were predictive of prior HIV testing (Data not shown). Older age was associated with prior HIV testing, but when adjusted for sex, knowledge, stigma, and education, its effect may have been due to chance (p=0.07). Prior HIV testing was not significantly associated with clinic location (p=0.65) or additional health clinic visits in the last 12 months (p=0.10) (data not shown). Because marital status had a significant association with HIV testing, we ran a second multivariable model of HIV testing history adjusting for marital status that revealed no effect modification.

Of the 1221 adults who underwent HIV testing, 130 were found to be seropositive, resulting in an overall prevalence of 10.6% (95% CI: 2.9% to 12.4%). HIV positive individuals tended to be older than uninfected individuals (p < 0.01), and had a greater number of sexual partners in the last 12 months (p = 0.05) (Table 2). HIV status was not significantly associated with either patient sex (p = 0.34) or prior HIV testing (p = 0.86), though adults previously tested for HIV had a lower HIV prevalence (10.1%) than those never tested (11.3%). HIV prevalence in Kanchindu (6.4%) was significantly lower than in the other three sites (p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Population Characteristics by HIV Status in rural southern Zambia, 2008

| HIV+ | HIV− | Combined | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%), unless otherwise indicated | (n=130) | (n=1091) | (n=1221) | |

| Female Sex | 88 (68%) | 787 (72%) | 875 (72%) | 0.34 |

| Age in years (IQR) | 34 (26, 38.8) | 29 (21.5, 38) | 30 (22, 38) | <0.01 |

| Clinic Site | <0.01 | |||

| Kanchindu | 27 (21%) | 397 (36%) | 424 (35%) | |

| Mboole | 23 (18%) | 133 (12%) | 156 (13%) | |

| Simpweze | 49 (38%) | 371 (34%) | 420 (34%) | |

| Zyangale | 31 (24%) | 190 (17%) | 221 (18%) | |

| Education, None or some primary | 12 (38%) | 111 (41%) | 123 (41%) | 0.85 |

| Marital Status | 0.25 | |||

| Single | 2 (7%) | 36 (15%) | 38 (14%) | |

| Unmarried, in a relationship | 2 (7%) | 41 (17%) | 43 (16%) | |

| Married | 24 (77%) | 159 (65%) | 183 (67%) | |

| Widowed | 3 (10%) | 8 (3%) | 11 (4%) | |

| Number of wives | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | 0.74 |

| Number of sexual partners | 1 (1, 2.5) | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | 0.05 |

| Travel time to nearest clinic (min) | 120 (60, 120) | 60 (30, 120) | 60 (30, 120) | 0.20 |

| Clinic visits in last 12 months, Noned | 5 (18%) | 64 (25%) | 69 (24%) | 0.57 |

| Never previously tested for HIVe | 16 (50%) | 125 (47%) | 141 (47%) | 0.86 |

| Time since last HIV test | 0.49 | |||

| < 12 months ago | 4 (36%) | 39 (37%) | 43 (37%) | |

| 12-24 months ago | 3 (27%) | 44 (42%) | 47 (40%) | |

| > 24 months ago | 4 (36%) | 23 (22%) | 27 (23%) | |

| Little or no knowledge of HIV and testing f | 9 (28%) | 100 (36%) | 109 (36%) | 0.47 |

| No Stigma towards PLWHAg | 13 (41%) | 122 (44%) | 135 (44%) | 0.83 |

| Personally Favorable toward PITCh | 21 (96%) | 187 (96%) | 208 (96%) | 0.71 |

| Partner seen as favorable toward PITCh | 22 (85%) | 182 (86%) | 204 (86%) | 0.90 |

|

| ||||

| Testing referral group | 0.58 | |||

| Standard non-PITC groupi | 54 (42%) | 486 (45%) | 540 (44%) | |

| PITC group | 76 (59%) | 605 (56%) | 681 (56%) | |

| Prior indication(s) for referral for HIV testingj | 86 (66%) | 676 (62%) | 762 (62%) | 0.40 |

Continuous variables are reported as medians (interquartile range).

Percentages are computed using the number of survey respondents with a non-missing value.

To compare the distribution of study characteristics by testing group, we employ chi-square tests. Similarly, we use a two-sample rank sum test for continuous variables by testing group.

p-value for No clinic visits vs. One or more clinic visits in past 12 months.

p-value for Never tested vs. previously tested for HIV.

p-value for No vs. Partial or full knowledge of HIV.

PLWHA means persons living with HIV or AIDS. p-value for No stigma vs. Partial or high stigma.

PITC means provider-initiated testing and counseling. p-value for Very or somewhat in favor of PITC vs. Very or somewhat opposed.

Standard non-PITC group includes patients referred for testing based on client request and/or clinical presentation who did not receive additional opt-out referral means voluntary counseling and testing.

p-value for Prior testing indication (client-request and/or clinical) vs. No prior indication

HIV prevalence did not differ by testing referral type (Table 2). HIV prevalence in the PITC group was 11.2% (95% CI 8.8% to 13.5%), whereas prevalence in the standard non-PITC group was 10.0% (95% CI 7.5% to 12.5%). Among all patients who requested HIV testing, prevalence was 10.4%. In all patients whose clinical presentation prompted referral for HIV testing, prevalence was 16.3%. In the subgroup of PITC patients without additional indication for testing (i.e., no client request or clinical presentation implicating HIV), prevalence was 9.6%. There was no significant difference in HIV prevalence rates according to testing strategy (p = 0.08). Using 6 providers PITC detected 76 cases of HIV, while standard non-PITC detected 54 cases with 16 providers. Thus, PITC detected more than three times more HIV infections per practitioner than standard non-PITC (12.7 vs. 3.4).

Multivariable analysis of HIV status adjusting for selected patient characteristics did not alter our results (Table 3). The PITC group was not associated with a lower prevalence of HIV than the standard non-PITC group (OR: 1.01; 95% CI 0.67 to 1.52; p = 0.95). Moreover, when compared to all study patients who either requested testing and/or had a clinical presentation suggesting HIV, the subgroup of PITC patients without additional indications for HIV testing did not have a statistically different HIV prevalence (OR: 0.83; 95% CI 0.55 to 1.24; p = 0.36).

Table 3.

Predictors of HIV Infection in rural southern Zambia, 2008

| Odds Ratio | Lower 95% | Upper 95% | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| 15 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.28 | <0.001 |

| 25 (ref) | 1 | |||

| 35 | 1.94 | 1.47 | 2.58 | |

| 49 | 0.61 | 0.29 | 1.28 | |

|

| ||||

| Male | 1.37 | 0.90 | 2.08 | 0.15 |

|

| ||||

| Clinic Site | ||||

| Simpweze (ref) | 1 | 0.003 | ||

| Kachindu | 2.55 | 1.40 | 4.67 | |

| Mboole | 2.10 | 1.25 | 3.53 | |

| Zyangale | 2.51 | 1.44 | 4.39 | |

|

| ||||

| PITC Groupa | 1.01 | 0.67 | 1.52 | 0.95 |

PITC means Provider-initiated testing and counseling; p-value for PITC group vs. Standard non-PITC group.

Of the patients who completed questionnaires, most (73%) reported prior knowledge of the concept of routine opt-out HIV testing, and 96% reported being “in favor” of PITC. Previous HIV testing was associated with knowledge of PITC (p=0.02) (data not shown).

Patients Declining HIV Testing

Due to clinic limitations in monitoring patient flow, it was logistically not possible to track adults who either did not consent for HIV testing or defaulted prior to receiving HIV testing. However, among those not receiving HIV testing, 89 completed questionnaires. This sample was compared to the 317 adults with questionnaires who were tested. They were found to be similar in all baseline demographic characteristics and attitudes toward PITC. Information regarding reasons for declining an HIV test was not formally assessed. Anecdotally, the most common reasons cited for declining an HIV test were known HIV positivity, recent prior HIV testing, and religious/cultural conflicts.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study in a rural African setting to compare HIV prevalence rates based upon screening protocol—PITC opt-out testing vs. standard non-PITC testing per client request or clinical referral. We found HIV prevalence to be comparable between the two groups. Moreover, the subset of asymptomatic patients referred by PITC who did not request testing had a similar rate of HIV infection as those who had. This suggests that—at least in rural Zambia—HIV prevalence among patients from the general patient population may equal that in traditionally defined volunteering or high-risk groups who have served as targets of standard non-PITC programs. Opt-out testing increased the number of patients tested per practitioner by three times compared to standard non-PITC, and also increased the number of HIV-infected persons detected per practitioner more than three-fold. Of the 459 PITC patients who lacked other reasons for testing, 44 (9.6%) were found to be HIV positive and referred for ART who would not have been screened using a standard non-PITC approach.

The overall HIV prevalence in 2008 of 10.6% in our study population is slightly higher than estimates for the surrounding general rural population in 2008 (12% nationally, 5-9.9% regionally).22,23 This likely reflects the fact that our group of clinic patients may be sicker than the general public as many of them came to the mobile clinic services because they had a chief complaint. Lower HIV prevalence and higher volume of standard non-PITC testing relative to PITC in Kanchindu may in part reflect an increased number of low-risk clients requesting testing as a result of the health-promoting activities of two mobile VCT clinics in Kanchindu shortly before our study. Although across Sub-Saharan Africa the percentage of adults who have ever been tested for HIV may be as low as 10%,1 we found a higher rate, with 53% of adults reporting having received HIV testing and counseling in the past. This may reflect earlier efforts by non-governmental organizations and the Zambian Ministry of Health to extend testing coverage in this region. Nevertheless, given the burden of disease in this region, this proportion remains lower than WHO recommendations, especially considering that most patients (63%) were not tested within the past year.

Whereas previous studies of opt-out HIV testing and counseling have focused on specific populations—infant,24 pediatric,25 antenatal,14,15,26-28 sexually transmitted infection,29 or tuberculosis patients30,31—our study addresses the need for PITC evaluation in a general adult patient population.32 Additionally, this report is one of the first prospective comparisons of PITC with a standard non-PITC approach, and our finding of approximately equal HIV detection rates between testing modalities parallels results of the few other direct comparisons published.29,30 Our study therefore avoids the confounding effects inherent to retrospective comparison analyses, including evolving population attitudes and disease epidemiology. Finally, by implementing both PITC and standard non-PITC approaches at the same sites, we reduce the confounding effect of inter-site variability.32

Although anecdotally we observed low levels of test refusal, one limitation of this study was our inability to quantify the exact number of adults opting out. We suspect a primary driver of test refusal was the long wait time (20 to 40 minutes) for pre- and post-test counseling; however, since wait times were experienced uniformly by all patients, we do not suspect PITC and standard non-PITC drop-out populations to differ greatly. Nevertheless, lack of data on the extent of or reasons for opting out indicates potential for sampling bias between referral groups. Additionally, long wait times resulted in 16 individuals defaulting prior to receiving test results, though since HIV test results had already been gathered for these individuals this did not affect data collection, analysis, or interpretation. Future high-volume PITC programs should incorporate methods to reduce wait time and premature patient departure. Additionally, since randomization of patients was not possible due to clinic logistical constraints, we instead randomized providers in an unblinded fashion. While this technique may have introduced additional bias between referral groups, we do not suspect significant effects on study results owing to low inter-provider variability in provider referral practices. Finally, an additional limitation of this study was our ability to detect a 50% difference in HIV detection rates with 80% power, though smaller undetected differences in detection rates may carry less clinical significance and even be permissible due to PITC’s corresponding ability to significantly augment total testing volume.

Our findings may have substantial implications for HIV prevention policies. Although the WHO recommends PITC for all areas with generalized epidemics,1 standard of care testing and counseling programs in most parts of sub-Saharan Africa still selectively target individuals who either request testing or possess clinical indications for it.2 Previous arguments in support of PITC have focused on its ability to detect greater absolute numbers of HIV positive patients.14,15,25,27,28,30,33 However, given the substantial increase in resources that would be required by PITC at every standing health facility, the persistence of standard approaches may reflect an implicit assumption that patients who request testing or exhibit risk factors for HIV infection have a higher likelihood of infection than the general adult population, and therefore deserve the focus of limited screening resources.17 Although further confirmatory studies are needed, our study may offer initial evidence against this hypothesis for high prevalence rural areas of southern Africa. Adults targeted by current standard testing modalities may not have a higher likelihood of HIV infection than the general adult patient population in the same area. This is particularly concerning since asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals without clear risk factors may be missed by standard screening programs.

PITC has been shown repeatedly to be highly acceptable in sub-Saharan Africa.14,15,21,24,26-28,34 The high percentage (76%) of adults in our study reporting at least one clinic visit during the last 12 months suggests the potential for national clinic-based PITC to increase HIV testing coverage.35 However, the implementation of PITC in our study required substantial human and material resources, and resulted in increased referrals for life-long ART. A national PITC program would consequently incur substantial additional costs at a time when targeted PEPFAR treatment funds seem to be leveling off.36 Given the potential that routine opt-out testing may identify proportionally just as many HIV-infected persons as current standard non-PITC programs, a formal cost-effectiveness comparison between the two approaches is needed. Although previous cost-effectiveness analyses of HIV counseling and testing have focused on net infections averted and resultant costs saved,37,38 future models should account for PITC’s potential to increase population knowledge about HIV/AIDS and thereby reduce stigma as well.32 Finally, although expansion of PITC to all established health facilities remains an urgent need in nations like Zambia, we suggest that mobile-based PITC—which may provide equivalent testing coverage while consolidating costs by limiting services to one site at any given time—when offered in conjunction with other medical services may be a relatively inexpensive and highly effective method for expanding HIV screening to remote regions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the dedicated staff of Zambia Medical Mission and Namwianga Mission in Kalomo, Zambia and all of the study volunteers. We also thank the Zambian Ministry of Health and Centre for Infectious Disease Research in Zambia for their assistance in supplying HIV test materials and identifying local ART referral sites. The work was supported in part, by the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and NIH grant R25TW007766.

Footnotes

Meetings at which parts of the data were presented:

1. Unite for Sight Global Health Conference; New Haven, CT; April 18-19, 2009

2. 71st Meeting of the Southeastern Clinical Club; Nashville, TN; January 29, 2010

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Guidance on provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in health facilities. World Health Organization; Geneva: [Accessed December 13, 2009]. 2007. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241595568_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matovu JKB, Makumbi FE. Expanding access to voluntary HIV counselling and testing in sub-Saharan Africa: alternative approaches for improving uptake, 2001-2007. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1315–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bassett IV, Walensky RP. Integrating HIV screening into routine health care in resource-limited settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(Suppl 3):S77–84. doi: 10.1086/651477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) World Health Organization (WHO) AIDS Epidemic Update, December 2009. UNAIDS; Geneva: [Accessed December 13, 2009]. 2009. Available at: http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2009/2009_epidemic_update_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2008 Report on the global AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS; Geneva: [Accessed December 21, 2009]. 2008. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/2008_Global_report.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Voluntary HIV-1 Counseling and Testing Efficacy Study Group Efficacy of voluntary HIV-1 counselling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, et al. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373:48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization (WHO) Towards universal access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector: progress report 2008. WHO; Geneva: [Accessed June 7, 2010]. 2008. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2006 Report on the global AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS; Geneva: [Accessed December 21, 2009]. 2006. 2006. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2006/default.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) World Health Organization (WHO) UNAIDS/WHO Policy Statement on HIV Testing. UNAIDS; Geneva: [Accessed December 13, 2009]. 2004. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/vct/en/hivtestingpolicy04.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Introduction of routine HIV testing in prenatal care--Botswana, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:1083–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Branson B. Current HIV epidemiology and revised recommendations for HIV testing in health-care settings. J Med Virol. 2007;79(Suppl 1):S6–10. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manzi M, Zachariah R, Teck R, et al. High acceptability of voluntary counselling and HIV-testing but unacceptable loss to follow up in a prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programme in rural Malawi: scaling-up requires a different way of acting. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:1242–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moses A, Zimba C, Kamanga E, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission: program changes and the effect on uptake of the HIVNET 012 regimen in Malawi. AIDS. 2008;22:83–87. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f163b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandisarewa W, Stranix-Chibanda L, Chirapa E, et al. Routine offer of antenatal HIV testing (“opt-out” approach) to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV in urban Zimbabwe. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:843–850. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.035188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monjok E, Smesny A, Mgbere O, et al. Routine HIV Testing in Health Care Settings: The Deterrent Factors to Maximal Implementation in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2010;9:23–29. doi: 10.1177/1545109709356355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartlett JG, Branson BM, Fenton K, et al. Opt-out testing for human immunodeficiency virus in the United States: progress and challenges. JAMA. 2008;300:945–951. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright RJ, Stringer JSA. Rapid testing strategies for HIV-1 serodiagnosis in high-prevalence African settings. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) National AIDS Programmes: A Guide to Monitoring and Evaluation. UNAIDS; Geneva: [Accessed December 21, 2009]. 2000. “Stigma and Discrimination Indicator 1.”. Available at: http://www.indicatorregistry.org/upload/UNAIDS.%20National%20AIDS%20Programmes.%20A%20guide%20to%20monitoring%20and%20.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Central Statistical Office (Zambia), Central Board of Health (Zambia), ORC Macro . Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2001-2002. Central Statistical Office, Central Board of Health, and ORC; Calverton, Maryland, USA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiser SD, Heisler M, Leiter K, et al. Routine HIV testing in Botswana: a population-based study on attitudes, practices, and human rights concerns. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) World Health Organization (WHO) AIDS Epidemic Update, December 2007. UNAIDS; Geneva: [Accessed December 13, 2009]. 2007. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/EpiUpdate/EpiUpdArchive/2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) World Health Organization (WHO) United Nations Children’s Fund . Epidemiological Fact Sheet on HIV/AIDS, Zambia: 2008 Update. UNAIDS; Geneva: [Accessed September 15, 2010]. 2008. Available at: http://apps.who.int/globalatlas/predefinedReports/EFS2008/full/EFS2008_ZM.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rollins N, Mzolo S, Moodley T, et al. Universal HIV testing of infants at immunization clinics: an acceptable and feasible approach for early infant diagnosis in high HIV prevalence settings. AIDS. 2009;23:1851–1857. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d84fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kankasa C, Carter RJ, Briggs N, et al. Routine offering of HIV testing to hospitalized pediatric patients at university teaching hospital, Lusaka, Zambia: acceptability and feasibility. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:202–208. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e31819c173f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez F, Zvandaziva C, Engelsmann B, et al. Acceptability of routine HIV testing (“opt-out”) in antenatal services in two rural districts of Zimbabwe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:514–520. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191285.70331.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Homsy J, Kalamya JN, Obonyo J, et al. Routine intrapartum HIV counseling and testing for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in a rural Ugandan hospital. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:149–154. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000225032.52766.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creek TL, Ntumy R, Seipone K, et al. Successful introduction of routine opt-out HIV testing in antenatal care in Botswana. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:102–107. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318047df88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leon N, Naidoo P, Mathews C, et al. The impact of provider-initiated (opt-out) HIV testing and counseling of patients with sexually transmitted infection in Cape Town, South Africa: a controlled trial. Implement Sci. 2010;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pope DS, Deluca AN, Kali P, et al. A cluster-randomized trial of provider-initiated (opt-out) HIV counseling and testing of tuberculosis patients in South Africa. J Acquir.Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48:190–195. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181775926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling of TB patients--Livingstone District, Zambia, September 2004-December 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collini P. [Accessed December 17, 2009];Opt-out HIV testing strategies. Clinical Evidence [database online] 2006 Available at: http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/downloads/2.Opt-out%20HIV%20testing%20strategies.pdf.

- 33.Bassett IV, Giddy J, Nkera J, et al. Routine voluntary HIV testing in Durban, South Africa: the experience from an outpatient department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:181–186. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31814277c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wanyenze RK, Nawavvu C, Namale AS, et al. Acceptability of routine HIV counselling and testing, and HIV seroprevalence in Ugandan hospitals. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:302–309. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.042580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ivers LC, Freedberg KA, Mukherjee JS. Provider-initiated HIV testing in rural Haiti: low rate of missed opportunities for diagnosis of HIV in a primary care clinic. AIDS Res Ther. 2007;4:28. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-4-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen J. HIV/AIDS: Botswana’s success comes at steep cost. Science. 2008;321:526–529. doi: 10.1126/science.321.5888.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Creese A, Floyd K, Alban A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of HIV/AIDS interventions in Africa: a systematic review of the evidence. Lancet. 2002;359:1635–1643. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stover J, Bertozzi S, Gutierrez J, et al. The global impact of scaling up HIV/AIDS prevention programs in low- and middle-income countries. Science. 2006;311:1474–1476. doi: 10.1126/science.1121176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]