Abstract

Although much attention has been paid to health disparities in the past decades, interventions to ameliorate disparities have been largely unsuccessful. One reason is that the interventions have not been culturally tailored to the disparity populations whose problems they are meant to address. Community-engaged research has been successful in improving the outcomes of racial and ethnic minority groups and thus has great potential for decreasing between-group health disparities. In this article, the authors argue that a type of community-engaged research, community-based participatory research (CBPR), is particularly useful for social workers doing health disparities research because of its flexibility and degree of community engagement. After providing an overview of community research, the authors define the parameters of CBPR, using their own work in African American and white disparities in breast cancer mortality as an example of its application. Next, they outline the inherent challenges of CBPR to academic and community partnerships. The authors end with suggestions for developing and maintaining successful community and academic partnerships.

Keywords: cancer, community, engagement, health disparities, research

Health disparities in the United States exist by race and ethnicity, gender, age, disability status, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status (SES), and geography and can occur in screening, incidence, mortality, survivorship, and treatment. To date, disparities by race and ethnicity have received the most attention and have been noted for all major diseases. It is alarming that the gap between racial and ethnic groups continues to increase through time for many diseases. Although cancer mortality decreased between 1975 and 2004 for the U.S. population as a whole, significant African American and white gaps persist for both women and men (Horner et al., 2009).

Disparities in health and health care began to receive major attention in 1998 with the launch of the Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities Initiative and its charge to public officials to address disparities. Subsequently, reducing health disparities is one of the two major goals of Healthy People 2010 and continues to be a major focus of federal research and policy interventions. Yet, despite this attention, little progress has been made in what is basic to the enterprise, namely, developing interventions to reduce disparities (Voelker, 2008). In a meta-analysis of interventions developed to reduce racial and ethnic disparities, Chin and colleagues (Chin, Walters, & Cook, 2007) concluded that too few interventions have been launched that are based on rigorous empirical studies, and that “multi-factorial, culturally-tailored interventions that target different causes of disparities hold the most promise” (p. 7).

Achieving the multifactorial approach to eliminating disparities suggested by Chin et al. (2007) requires that disciplinary scholars work more closely than they have traditionally done (Gehlert et al., 2010). Likewise, the culturally tailored interventions suggested can be achieved only when academic researchers draw on the knowledge and resources of communities vulnerable to adverse health conditions.

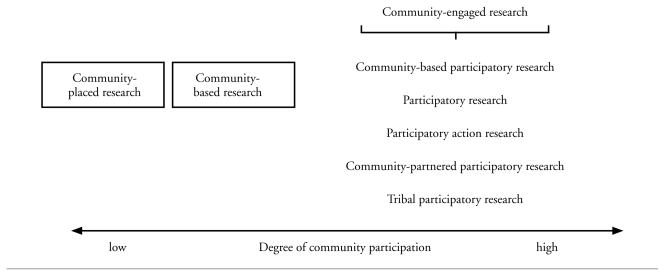

Community-engaged research (CEnR) is a means of drawing on the expertise and resources of communities that has proven effective in improving health outcomes among racial and ethnic group members (Two Feathers et al., 2005). Broadly defined, CEnR is a set of approaches that focuses on the creation of a working and learning environment between academic researchers and community stakeholders that extends from before a research project begins to beyond its completion (Ross et al., 2010). CEnR approaches can be arrayed along a continuum from low to high community engagement in research (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Categories of Research Involving the Community

Three approaches on the high end of community engagement are community-partnered participatory research, tribal participatory research, and community-based participatory research (CBPR). All three CEnR approaches hold potential for ameliorating health disparities, by virtue of their ability to improve health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority group members (see, for example, Wells et al., 2000), with consequent narrowing of the gap between groups. CBPR, which also has been referred to as participatory research or participatory action research, arguably, is the most versatile of the three approaches and thus, arguably, is the most useful for social work researchers. Although community-partnered participatory research and tribal participatory research share the same perspective as CBPR, they are tailored to specific partner groups. Community-partnered participatory research (Jones & Wells, 2007), for example, is more likely to be conducted by physicians than by members of other disciplines and takes into account their unique challenges, such as balancing the roles of clinician and researcher and having limited encounter time. Tribal participatory research is designed specifically to infuse the research process with an understanding of the impact of historical events on the lives of American Indians and Alaska Natives (Fisher & Ball, 2002, 2003). In the present article, we focus on CBPR as a means for ameliorating racial and ethnic disparities in health.

CBPR

CBPR is defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2010) as “a collaborative process involving researchers and community representatives; it engages community members, employs local knowledge in the understanding of health problems and the design of interventions, and invests community members in the processes and products of research” (p. 1). In addition, community members are invested in the dissemination and use of research findings and ultimately in the improvement of health outcomes. It is itself not a method or theory, but a perspective on research that can employ a variety of theories and methods from qualitative interviewing (Rhodes et al., 2007) to experimental designs (Wilcox et al., 2007).

The potential strength of CBPR in addressing health disparities comes from its hallmark of combining scientific rigor with community wisdom, reality, and action for change. The challenge is in finding the best possible balance between the academic and community perspectives and attributes, which can only be achieved through trust and communication. When community and academic input are in competition rather than in concert, channels of information are closed and energy toward change is lost. Yet there are myriad reasons for community stakeholders to withhold trust from academic researchers (Gamble, 1997; Washington, 2007).

The perspectives of academic researchers and community members differ at each stage of the research process. At the stage of formulating questions, for example, academics are concerned with questions that can be tested scientifically, whereas community members are more likely to favor questions that are meaningful to community residents. Similarly, academics turn to the scientific literature and theory as background knowledge to inform their investigations, whereas community stakeholders are more likely to turn to community voices and experiential knowledge. Both are important, and achieving the best possible balance between the two is essential for optimal outcomes to be achieved. Community and academic perspectives on each stage of the research process are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Steps to the Research Process as They are Viewed from the Community and Academic Perspectives

| Step to the Research Process | Community Perspective | Academic Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Formulating questions | Matches life experiences of residents | Testable |

| Obtaining background knowledge | Community voices: Experiential knowledge | Professional literature |

| Formulating a design | ||

| Sample | Those who know | Objectively obtained, sufficient statistical power |

| Constructs/measures | Meaningful to community | Psychometrically sound |

| Data collection | Culturally appropriate | Scientifically rigorous |

| Analysis | Through community experiences | Statistical methods |

| Evaluation results | Clinical significance | Statistical significance |

| Formulating conclusions | Relate to life experiences | Relate to original hypothesis/question |

| Disseminating results | Lay media, agency, and other community presentations | In scientific journals |

A number of methods and structures can be used to facilitate engagement with community, ranging from focus groups to long-term partnerships such as collaborations and coalitions. Each has its place as community and academic relationships develop. Because, by definition, the process extends beyond any one particular research project, it is important to think in the long term and build relationships that stand a good chance of being sustained through time.

Focus groups are face-to-face gatherings of about eight to 10 people brought together to discuss a particular topic (Edmunds, 1999). Their advantage is that they can be coordinated, conducted, and analyzed in a relatively short period of time, thus providing timely feedback. Their transitory nature, however, is a disadvantage, because it precludes a long-term relationship. Also, facilitator bias can be difficult to control, as can selection bias. Nonetheless, focus groups can provide important insight from the community, especially during formative stages of community and academic relationships. Community advisory boards or councils provide more ongoing feedback useful for setting research agendas, reviewing results, and advising on issues that arise throughout the research process. These boards should be constituted with stakeholders who not only are able to provide feedback when needed, but also are willing and sufficiently confident to provide critical feedback to academic researchers. Nothing is gained if these community advisory boards or councils meet infrequently and tacitly agree with the plans of academic researchers.

The ideal of community engagement, which often takes time to achieve, is community and academic coalitions or collaborations. These partnerships of academics, community residents and organizations, clinicians, and policymakers may span research projects. In so doing, they increase the odds of sustainable change by setting larger agendas with longer term goals.

USING CBPR TO INFORM HEALTH DISPARITIES RESEARCH: AN EXAMPLE

The Center for Interdisciplinary Health Disparities Research (CIHDR) was funded by the National Institutes of Health in 2003 with an overarching mission to better understand the determinants of health disparities and devise appropriate multilevel interventions to ameliorate disparities (Gehlert, Sohmer, et al., 2008). In their first six years of operation, CIHDR’s team of social, behavioral, and biological investigators focused on African American and white differences in breast cancer mortality. Two projects, one of which is CBPR, worked with African American women newly diagnosed with breast cancer living on Chicago’s predominantly African American South Side, who represented a wide range of SESs. Two projects used rodent models that mimic human breast cancer. The animal studies allow hypotheses generated in work with women to be tested experimentally by varying animals’ social conditions. The approximately 900-day life cycle of Sprague-Dawley rats, for example, allows social conditions, such as housing in natural social groups versus isolation, to be varied experimentally at various stages of the life cycle (Hermes et al., 2009).

The CIHDR team’s four mutually informative research projects together addressed the same shared research question, namely, how factors in women’s social environments contribute to the African American and white disparity in breast cancer mortality in the United States. Although white women in the United States are more likely than African American women to develop breast cancer (126.5 per 100,000 white women and 118.3 per 100,000 for African American) (Horner et al., 2009), African American women are 37 percent more likely to die from the disease (24.4 per 100,000 for white women and 33.5 per 100,000 for African American women) (Ries et al., 2008). The disparity is even higher in Chicago, with African American women 68 percent more likely than white women to die from breast cancer (Hirschman, Whitman, & Ansell, 2007).

CBPR has been essential to CIHDR’s success, for two main reasons. First, it provides a means of informing the science with community wisdom and experience. Second, it is a means of changing breast cancer practice and policy and ensuring that those changes are sustained through time, thus leading to a decrease in breast cancer disparities. To heighten their odds of success, CIHDR investigators followed a process of community engagement. They conducted focus groups in the South Side neighborhood areas of focus, then they added a robust community advisory council, and ultimately they helped to develop a community collaboration and partnerships with established community organizations.

Focus Groups

The first year of CIHDR operations was devoted to learning beliefs, attitudes, and concerns about breast cancer and its treatment among residents of Chicago’s South Side and checking that concepts and measures that investigators were thinking of using were deemed suitable and appropriate by community residents. Because no single community agency was well enough positioned to represent South Side concerns about breast cancer and related health issues, CIHDR used a grassroots recruiting approach to reach community stakeholders, in which investigators traveled to the 15 South Side neighborhood areas of research focus to listen to the voices of community residents.

After reviewing Chicago Department of Public Health data on each of the 15 neighborhood areas of focus to ensure that the composition of focus groups would appropriately reflect their demographics (that is, gender, SES, age, and Muslim versus Christian religion of residents), CIHDR staff distributed flyers in the neighborhoods; sent letters of introduction to aldermen, health care providers, and community-based and faith-based organizations; and spoke at community organizations, outlining CIHDR’s goals and projects and inviting adults over 18 years of age to take part in focus groups.

Over 1,300 people called the number provided to volunteer. We selected 503 to form two to three groups per neighborhood area that represented the demographics of the area and would result in groups heterogeneous in terms of age, gender, and SES, while avoiding situations in which some people in the group would be dominant over others (for example, having a low-wage worker and administrator from the same company). Two to three group interviews were conducted in each of the 15 neighborhood areas—depending on the size of their population—in spots such as park district facilities or community centers and in other places that were considered welcoming by residents. Churches were avoided, because members of some faiths might not feel comfortable in the facilities of other faiths.

Each group had 10 to 12 participants and was facilitated by two specially trained African American facilitators living in or familiar with South Side neighborhood areas. The interview guide followed the approach outlined by Balshem (1993) in Cancer in the Community, in which participants were asked broad questions to stimulate discussion, without biasing their nature or direction of that discussion (for example, “What comes to mind when you think of breast cancer, the disease itself?”). The 49 focus group interviews, which each lasted from one and a half to two hours, were recorded, professionally transcribed, and analyzed using NVivo software (Masi & Gehlert, 2009; Salant & Gehlert, 2008). After each focus group interview, participants were asked to review survey instruments that were candidates for use in scientific investigations and to provide feedback on their suitability and relevance to their life experiences and concerns.

Data from the focus groups influenced CIHDR investigations in two principal ways. First, focus group content suggested new lines of scientific inquiry. As an example, many members spoke of increasing difficulty in locating safe and affordable housing in South Side neighborhoods, with a consequent need for frequent moves to secure that housing. In response to this content, the two animal projects added experiments to measure coping when animals were moved to new environments (that is, new social grouping or caging). Second, feedback from focus group members who volunteered to review potential survey instruments resulted in the decision not to use some instruments that investigators had originally selected for use, either because the instruments did not capture the content intended or because their language was deemed inappropriate by community members.

Community Advisory Board

Through the 49 focus groups, CIHDR investigators met a number of women who expressed interest in working with the team to further CIHDR’s scientific mission. Through time, we invited five of these women and representatives of community organizations to form a community advisory board (CAB). The CAB met at regular intervals to advise investigators and help with planning of activities as the CIHDR team began to disseminate the results of its research.

The first activity in which the CAB partnered with investigators was the half-day South Side Breast Cancer Conference held at the Metropolitan Apostolic Community Church on the South Side during the second year of CIHDR’s operations. The purposes of the conference were to disseminate an overview of results of the 49 focus groups to those who took part in individual focus groups and others in the community and to turn the concerns expressed in focus groups into action steps. After presentation of results and a panel discussion by South Side service providers, the audience broke into groups of eight, each with one community and one academic facilitator. Each group independently developed a list of three action steps, which were presented to the reconvened audience. A moderator then helped the audience to prioritize the steps.

The action step ranked as most important was developing messages about wellness for 12- to 16-year-old South Side youths. To implement this action step, the CAB and investigators decided to use input from CIHDR’s five South Side Chicago high school students who were serving as summer apprentices to CIHDR’s research projects. With funding provided by the university’s community affairs office, which enabled them to hire a videographer, the summer apprentices and CAB members planned and developed a five-part, two-and-a-half-hour DVD on wellness titled Livin’ in Your Body 4 Life. A community audience screened the DVD and provided written feedback. After the DVD was edited, it was accepted into the health curriculum of the Chicago Public Schools.

The CAB met regularly with investigators to advise on issues as they arose. The group also helped investigators to plan the next phase of investigations and to shape their applications for funding. Members of the CAB and summer apprentices presented findings either independently or with CIHDR investigators at professional meetings and in community venues.

Community Collaboration

In the fourth year of CIHDR funding, a group of dedicated community members; academic investigators from a number of local universities, including a sister health disparities center at the University of Illinois at Chicago that was funded by the same mechanism as CIHDR (Warnecke et al., 2008); and clinicians formed a collaboration named the Metropolitan Chicago Breast Cancer Task Force. The CIHDR team extracted focus group comments about South Side Chicago breast cancer services for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, which were used to inform the task force’s direction. A task force’s first report, titled “Breast Cancer in Chicago: Eliminating Disparities and Improving Mammography Quality” (Sinai Urban Health Institute, 2007), was issued in 2007.

By 2009, the task force had grown to include 100 organizations and named its first executive director (Ansell et al., 2009). The collective efforts of the individuals and organizations involved almost certainly could help to ensure that changes made are sustained through time.

Community and Academic Partnerships

When CIHDR was developed in 2003, no community organizations were considered well enough positioned to represent South Side Chicago concerns about breast cancer and related issues; however, two changes had occurred by the end of CIHDR’s first five years of funding. First, CIHDR investigators had a much better idea of how breast cancer affected the lives of African American women living on Chicago’s South Side and their communities and, thus, a better idea of the direction that their inquiries should take. For example, the group now realized the importance of neighborhood social structures and needs, such as safe and affordable housing, which pointed in the direction of community organizations with unique expertise and resources. Second, new community collaborations like the Metropolitan Chicago Breast Cancer Task Force had been formed, which provided opportunities for interacting with a variety of individuals and groups.

The CIHDR team gathered evidence for its model of how social environmental factors affect African American and white breast cancer disparities (Gehlert, Sohmer, et al., 2008). The team began to develop an intervention to address those disparities, which will be tested on the South Side of Chicago in the future. The intervention aims at neighborhood-level factors that affect psychological functioning and influence clinical and biological outcomes (Gehlert, Mininger, Sohmer, & Berg, 2008). The intervention aims to provide social support and assistance with negotiating complex systems, such as those that provide housing and mental health services.

Because it is not possible to remain abreast of changing social services in South Side Chicago neighborhoods from the vantage point of an academic campus, we have formed a partnership with an organization that provides housing, employment, and support services and meals to residents in need. They will help to shape the intervention and provide information on changing services. In addition, the team will partner with a nearby free health clinic and a faith-based health clinic for the underserved residents. These three partners are located within the 15 South Side neighborhood areas and help us to span the territory.

The CIHDR vertically oriented model of social environment and gene interactions starts at the top with race, poverty, disruption, and neighborhood crime; moves to social isolation, acquired vigilance, and depression; then to stress-hormone dynamics; and finally to cell survival and tumor development (Gehlert, Sohmer, et al., 2008). To determine whether the CIHDR model operates in the same way in rural areas, we plan to launch the research in a rural impoverished area of Missouri, with African American and white women. This entails not only conducting focus groups in the area, but also partnering with grassroots community organizations in the region. This is possible because, unlike in our initial work in Chicago, we have some idea of the social factors that influence gene expression among vulnerable women. We have established partnerships with a family resource center and shelter for women, a federally qualified health center, and a community development organization.

CONCLUSION

The CIHDR team of social, behavioral, and biological investigators began its operations by listening to community voices to understand how the life experiences and social circumstances of South Side Chicago residents might “get under the skin” to influence biological and clinical outcomes that lead to African American and white breast cancer disparities. Through time, community engagement in the research process increased and changed the team’s research trajectory and approach. Input from the community, which through time took the form of partnership in the research process, greatly informed CIHDR’s science-enhanced academic investigators’ ability to formulate and answer questions. Had the academic members of the team operated without community input, they would have made a number of serious errors, including exploring the wrong concepts, choosing the wrong measures, and misinterpreting results. Absent community input, the team would have produced results, and those results might have been methodologically sound but meaningless.

Establishing community partnerships is a gradual process that requires humility on the part of academics and genuine desire to ground the research process in the lived experiences of the people most affected by the disparities. It likewise requires trust on the part of community stakeholders. The CIHDR team found that codifying agreements with community partners well in advance of the research project makes the inevitable conflicts manageable that arise when parties with disparate perspectives work together. A number of sources provide examples of successful memorandums of understanding (see, for example, California Breast Cancer Research Program, 2010). Likewise, frequent meetings, though difficult to achieve, are essential for maintaining a workable partnership. Each side has a mandate to listen to the other and articulate its perspective clearly.

CBPR has the potential to decrease health disparities in screening, incidence, mortality, survivorship, and treatment of disease in three major ways: (1) by improving health outcomes for racial and ethnic groups, thus decreasing gaps between groups; (2) by ensuring that the research plans of academic investigators are informed by community realities and cultures as opposed to being developed in the academic cultures of universities; and, as Chin et al. (2007) concluded on the basis of their meta-analysis, (3) by developing interventions that are culturally tailored, because they are the most successful at ameliorating health disparities.

Of the types of CEnR presented, CBPR is particularly useful for social workers doing health disparities research. This is because social workers consider a range of disparity populations and a plethora of diseases and conditions for which disparities exist, and CBPR is flexible enough to allow for work with a variety of groups and conditions. Although the CIHDR experience was buoyed by external funding over time, sustainable gains have been achieved by much less resource-rich projects in high-risk communities for conditions such as diabetes (Carlson et al., 2006; Jenkins et al., 2010). The key is to establish relationships between academics and community stakeholders that can be maintained over time, which is a natural enterprise for social workers. This may span times with and without outside funding. Although time consuming on the part of researchers, the ties are often those already in place for social workers. The payoff is extremely rich research that is more easily translatable into culturally tailored interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grant number P50 ES012383-02 from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Contributor Information

Sarah Gehlert, E. Desmond Lee Professor of Racial and Ethnic Diversity, George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis.

Robert Coleman, Retired. At the time of the research, he was director of social work, Cook County Health Systems, Chicago.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Community-based participatory research. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/about/cpcr/cbpr/cbpr1.htm.

- Ansell D, Grabler P, Whitman S, Ferrans C, Burgess-Bishop J, Murray L, et al. A community effort to reduce the black/white breast cancer mortality disparity in Chicago. Cancer Causes & Control. 2009;20:1681–1688. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balshem M. Cancer in the community. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- California Breast Cancer Research Program. Community research collaboration: Memorandum of understanding. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cbcrp.org/community/CRCMOUHandout.pdf.

- Carlson BA, Neal D, Magwood G, Jenkins C, King MG, Hossler CL. A community-based participatory health information needs assessment to help eliminate diabetes information disparities. Health Promotion Practice. 2006;7(3 Suppl):213S–222S. doi: 10.1177/1524839906288694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin M, Walters AE, Cook SC. Interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5 Suppl):7S–28S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds H. The focus group research handbook. Chicago: NTC Business Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Ball TJ. The Indian Family Wellness Project: An application of the tribal participatory research model. Prevention Science. 2002;3:235–240. doi: 10.1023/a:1019950818048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Ball TJ. Tribal participatory research: Mechanisms of a collaborative model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;32:207–216. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000004742.39858.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble V. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1773–1778. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlert S, Mininger C, Sohmer D, Berg K. (Not so) gently down the stream: Choosing targets to ameliorate health disparities [Editorial] Health & Social Work. 2008;33:163–167. doi: 10.1093/hsw/33.3.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlert S, Murray A, Sohmer D, McClintock M, Conzen S, Olopade O. The importance of transdisciplinary collaborations for understanding and resolving health disparities. Social Work in Public Health. 2010;25:408–422. doi: 10.1080/19371910903241124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehlert S, Sohmer D, Sacks T, Mininger C, McClintock M, Olopade O. Targeting health disparities: A model linking upstream determinants to downstream interventions. Health Affairs. 2008;37:339–349. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes GL, Delgado B, Tretiakova M, Cavigelli SA, Krausz T, Conzen SD, McClntock MK. Social isolation dysregulates endocrine and behavioral stress while increasing malignant burden of spontaneous mammary tumors. PNAS. 2009;106:22393–22398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910753106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman J, Whitman S, Ansell D. The black:white disparity in breast cancer mortality: The example of Chicago. Cancer Causes & Control. 2007;18:323–333. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0102-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Howlader N, et al., editors. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2006. 2009 Retrieved from http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006.

- Jenkins C, Pope C, Magwood G, Vandemark L, Thomas V, Hill K, et al. Expanding the chronic care framework to improve diabetes management: The REACH case study. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2010;4(1):65–79. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and community engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297:407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi C, Gehlert S. Perceptions of breast cancer and its treatment among African-American women and men: A qualitative study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24:408–414. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0868-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Eng E, Hergenrather KC, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Montaño J, Alegria-Ortega J. Exploring Latino men’s HIV risk using community-based participatory research. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2007;31(2):146–158. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2004. 2008 Retrieved from http://seer.cancer.gov/cst/1975_2004/results_merged/topic_annualrates.pdf.

- Ross LF, Loup A, Nelson RM, Botkin JR, Kost R, Smith GR, Gehlert S. The challenges of collaboration for academic and community partners in a research partnership: Points to consider. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2010;5:19–31. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salant T, Gehlert S. Collective memory, candidacy, and victimization: Community epidemiology of breast cancer. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2008;30:599–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinai Urban Health Institute. Breast cancer in Chicago: Eliminating disparities and improving mammography quality. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.sinai.org/urban/publications.asp.

- Two Feathers J, Kieffer EC, Palmisano G, Anderson M, Sinco B, Janz N, et al. Racial and ethnic approaches to community health (REACH) Detroit partnership: Improving diabetes-related outcomes among African American and Latino adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1552–1560. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelker R. Decades of work to reduce disparities in health care produce limited success. JAMA. 2008;299:1411–1413. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.12.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke RB, Oh A, Breen N, Gehlert S, Paskett E, Tucker KL, et al. Approaching health disparities from a population perspective: The National Institutes of Health Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1608–1615. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.102525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington HA. Medical apartheid. New York: Doubleday; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Meredith L, Unützer J, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S, Laken M, Bopp M, Gethers O, Huang P, McClorin L, et al. Increasing physical activity among church members: Community-based participatory research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]