Abstract

Background

The rapid increase of obesity and diabetes risk beginning in youth, particularly those from disadvantaged communities, calls for prevention efforts.

Objective

To examine the impact of a curriculum intervention, Choice, Control, and Change (C3), on the adoption of the energy balance related behaviors of decreasing sweetened drinks, packaged snacks, fast food, and leisure screen time, and increasing water, fruits and vegetables, and physical activity, and on potential psychosocial mediators of the behaviors.

Design

Ten middle schools in low-income New York City neighborhoods were randomly assigned within matched pairs to either intervention or comparison/ delayed control conditions during the 2007–2008 school year.

Participants

562 inner city seventh grade students in the intervention condition, and 574 in the comparison condition.

Intervention

Students received the 24 C3 lessons that used science inquiry-based investigations to enhance motivation for action, and social cognitive and self-determination theories to increase personal agency and autonomous motivation to take action.

Main outcome measures

Self-report instruments to measure energy balance related behaviors targeted by the curriculum, and potential psychosocial mediators of the behaviors.

Analyses

ANCOVA with group (intervention/control) as a fixed factor and pre-test as covariate.

Results

Students in intervention schools compared to the delayed intervention controls reported consumption of significantly fewer sweetened drinks and packaged snacks, smaller sizes of fast food, increased intentional walking for exercise, and decreased leisure screen-time, but showed no increases in their intakes of water, fruits, and vegetables. They showed significant increases in positive outcome expectations about the behaviors, self-efficacy, goal intentions, competence, and autonomy.

Conclusions

The C3 curriculum was effective in improving many of the specifically targeted behaviors related to reducing obesity risk, indicating that combining inquiry-based science education and behavioral theory is a promising approach.

INTRODUCTION

Healthful diets are important during childhood and adolescence for growth, development and overall health. Yet the majority of the nation’s youth do not meet all the dietary guidelines (1). Additionally, there is concern about the increasing rate of overweight and obesity among youth because of the strong association with risk of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidemias, and type 2 diabetes (2,3). About a third of youth are obese or overweight—with even higher rates in some ethnic groups, such as African-Americans and Hispanics (4–6), resulting in considerable public health consequences. The longer individuals have these conditions, the greater the risk of complications, resulting in discomfort, ill health, and days lost from school and work. Because overweight involves appearance, there are also psychosocial consequences including social alienation, low self-esteem, and discrimination.

Consequently, there have been calls for actions to prevent obesity involving multifaceted approaches and venues, including schools (7,8). A number of systematic reviews have attempted to identify effective prevention strategies (9–16). These reviews have noted that studies differ considerably in terms of outcome measures, research design, theoretical framework, and the nature, quality and duration of the intervention, making it difficult to generalize from the findings (13–18).

Few studies have been conducted with middle school youth and have had inconsistent impacts on weight measures and behaviors (19–25). Thus, findings from these programs do not provide clear guidance on specific elements of effectiveness for school-based programs to reduce excessive weight gain (9–16). They do suggest, however, that while changing food and physical activity environments is very important, a strong curriculum to facilitate individual change is likely also crucial (11,13,15). Research is thus needed on how best to assist youth to develop healthy behaviors and maintain a healthy weight.

Social cognitive theory (SCT) has been widely used in childhood obesity prevention studies with some success (9–15). It proposes that personal, behavioral, and environmental factors work in a dynamic and reciprocal fashion to influence behavior (26). The sense of ability to exert personal influence over one’s environment as well as over one’s own behaviors is described as personal agency (27, 28). Though it is often considered to be synonymous with self-efficacy, personal agency is a collective, overarching system that is characterized by four core capacities: forethought, the anticipation of likely consequences of taking action, usually called “outcome expectations”; intentionality, a proactive commitment to a future course of action; self-efficacy, people’s confidence in their ability to organize and execute particular behaviors in specific domains and situations and to overcome specific barriers, and self-regulation of behavior through self-assessment and goal-setting processes. These capacities, and hence personal agency, can be enhanced through motivational activities and skill building.

A concept somewhat similar to personal agency is autonomous motivation from self-determination theory (SDT), which refers to people’s ability to reflect on, and engage in, actions with a full sense of choice (29, 30). SDT postulates that individuals have innate psychological needs for autonomy, competency, and relatedness, which, when satisfied, enhance their autonomous motivation and well-being (29). Autonomy refers to the need to experience one’s actions as results of volitional choice, which thus brings satisfaction; competence refers to the generalized need to experience oneself as capable and competent in controlling the environment and being able to reliably predict outcomes; and relatedness refers to the need to experience satisfaction in involvement with the social world (29,30). Providing a meaningful rationale for taking action and support for autonomy are seen as important (29,30,31). SDT has been used in a few studies of health behaviors, in particular physical activity, with some positive impacts (32–35). Taken together, the studies suggested that integrating the central concepts of SDT with SCT in this study involving youth would be both novel and likely to increase effectiveness.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of a science and nutrition education middle school curriculum, Choice, Control and Change (C3), on behaviors related to obesity risk reduction, or “energy balance related behaviors” (EBRBs) (36) and on potential mediators of behavior change based on constructs from SCT and SDT (26,28, 32,37). The specific EBRBs indentified by researchers as contributing to obesity risk reduction (1,8,38) and over which middle school youth have some control are: eating more fruits and vegetables, drinking more water, increasing physical activity, and decreasing intakes of sweetened beverages and packaged snacks, eating at fast food restaurants, and leisure screen time.

METHODS

Evaluation Study Design and Participants

The study used a pre-post, cluster randomized intervention-control design and was conducted in the 2007–2008 school year. Ten middle schools in underserved, low-income neighborhoods within the same school district in New York City were matched on school size, race/ethnicity, free/reduced lunch percentage, and reading and math test scores. One school of each matched pair was randomly assigned to the intervention condition (C3 curriculum) and the other into the comparison condition (standard science curriculum of equal intensity and duration, receiving C3 the next term as a delayed intervention). The schools were identified and recruited in collaboration with the school district’s science education coordinator. All seventh grade classes within the schools participated, with 20 intervention classes (562 students) and 21 comparison classes (574 students). The mean age was 12, range 11–13, and each condition had about 25% African American students, 70% Latino students (predominantly Dominican and Puerto Rican) and 5% others. Approximately 51% in both groups were male. The rate of free and reduced lunch was 74% for the control group and 83% for the intervention group (difference between groups is not significant) for a mean of 78%. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Teachers College Columbia University and the New York City Board of Education and involved passive consent from the parents, where parents who did not wish for their child to take part in data collection procedures could refuse consent.

Choice, Control and Change (C3) Intervention

The conceptual basis of the curriculum was that body size is clearly the result of complex interactions between biology, environment and personal behavior. It has become increasingly recognized that the modern industrialized environment is highly obesigenic and plays a prominent role in this interaction (39,40). Youth, particularly those in underserved, low-income neighborhoods, need a sense of personal agency to act within this challenging environment. The goal of the curriculum was thus to assist middle school youth to acquire motivations and skills to become both competent navigators of the current food system and sedentary environment and agents in creating their personal food and activity world (41).

The educational approach was based on using science as inquiry-based investigations, focusing on the scientific method rather than on a set of facts to be learned, to help youth develop a rationale and increased motivation for taking action, and behavioral theory to provide skills for how to take action.

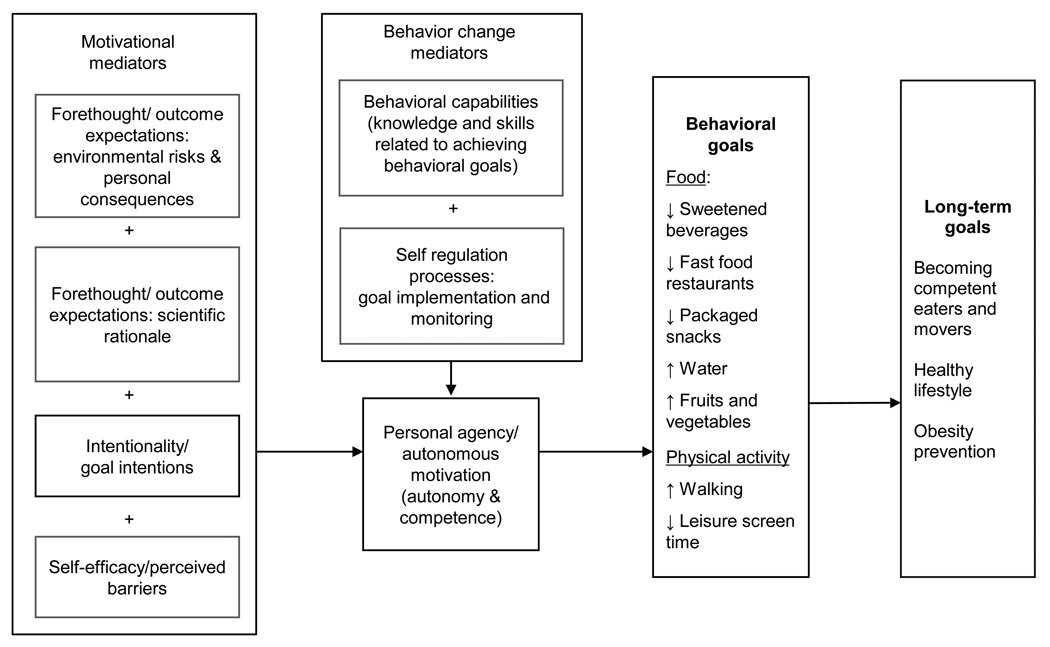

Young children make their food choices based primarily on what they like. But by middle school, cognitive-motivational processes also influence food choice through children’s increasing ability to link consequences to their actions (42, 43). Hence an emphasis on psychosocial variables and skills would likely be useful. For the intervention, the mediators from SCT and SDT (30,44,45) were combined to create an integrated intervention theory model or theoretical framework, a process suggested by researchers so as to potentially enhance effectiveness (46). The model is shown in the figure. The actual process of translating the theory model into a curriculum was based on a six-step procedural model for designing theory-based interventions (47).

Choice, Control & Change (C3) middle school curriculum theoretical model1

1The C3 curriculum is based on Social Cognitive Theory and Self-Determination Theory (28,30). It uses educational strategies to address the potential motivational mediators of outcome expectations, goal intentions, and self-efficacy/perceived barriers as well as behavior change mediators of knowledge and skills and self-regulation processes. Together these increase personal agency/autonomous motivation in order to achieve the targeted obesity risk reducing behaviors shown, with the long term goal of improving health and preventing obesity.

The C3 curriculum consisted of 24 lessons of 45 minutes each, taught by science teachers most school days over eight to ten weeks. However, some lessons spanned multiple days resulting in about 33 C3 sessions per class. The curriculum addressed selected national science standards in biology, in particular energy balance and science as inquiry (43,48). Specific educational activities were based on a systematic science-inquiry procedure that provided a scientific rationale for taking action - Questioning, Experimenting, Searching, Theorizing, and Applying to Life (QuESTA) (41), and also addressed SCT and SDT theory constructs or potential motivational and behavior change variables to enhance personal agency. A process of guided goal-setting was also used (49), whereby the curriculum sets out several behaviors from which youth choose one. Illustrative examples of how theory variables were translated into educational activities are shown in Table 1. The curriculum is described in detail elsewhere (50).

Table 1.

Use of theoretical model based on social cognitive and social determination theories to design a middle school lifestyle education intervention

| Psychosocial mediators from theoretical model | Examples of educational activities |

|---|---|

| Forethought/ outcome expectations: environmental risks and personal consequences |

|

| Forethought/ outcome expectations: scientific rationale |

|

| Intentionality/goal intentions |

|

| Self-efficacy/perceived barriers |

|

| Behavioral capabilities (knowledge and skills related to achieving behavioral goals) |

|

| Self-regulation processes: Goal implementation and monitoring |

|

| Personal agency/Autonomous motivation (autonomy & competence) |

|

Teachers received one intensive, three-hour long pre-intervention professional development session and one in the middle of the intervention. Because each teacher taught several or all the science classes for a given grade in a school, there were eight teachers total in the five intervention schools. Two research staff members who had been science teachers attended one third of all classroom sessions of each teacher and met with each teacher weekly during their preparation period or lunch hour for about 45 minutes to go over upcoming lessons, provide support, trouble shoot, and give feedback. In addition, to assure high fidelity to the curriculum, teachers received all necessary supplies throughout curriculum implementation.

Outcome measures

Behavioral outcomes

The primary outcome was whether students adopted the seven targeted behavior categories. The 30-item food frequency behavioral measure used –the EatWalk Survey (EW) – was a modification of the validated 84-item Block food frequency instrument for children which measures both frequency and portion sizes (51). Only those items that measured the specific C3 behaviors were used. The measures are summarized here and scoring details are shown in the footnotes on Table 2: frequency and portion sizes of fruits and vegetables during meals and snacks; water at meals, snacks, and in between; processed, packaged snacks; sweetened beverages at meals, snacks, and in between; and when eating at fast food restaurants. For physical activity, the measures included frequency of purposively walking or taking the stairs for exercise and engaging in leisure screen time.

Table 2.

Impact of Choice, Control & Change (C3) middle school curriculum on behavioral outcomes

| Adjusted Post Mean (SD) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Fh | ph | |||

| Intervention (n=460) |

Control (n=437) |

||||

| Food Choices | |||||

| Days previous week (0–7) | 3.61 (2.2) | 3.51 (2.4) | 1.41 | .235 | |

| Fruit: meals | |||||

| Pieces per daya (0–4) | 1.98 (1.1) | 2.06 (1.2) | .01 | .909 | |

| Days previous week (0–7) | 3.25 (2.5) | 3.78 (2.8) | 4.22 | .040 | |

| Fruit: snacks | |||||

| Pieces per daya (0–4) | 1.99 (1.4) | 2.34 (1.5) | 5.55 | .019 | |

| Days previous week (0–7) | 2.59 (2.1) | 2.49 (2.1) | 1.18 | .277 | |

| Vegetables: meals | |||||

| Cups per daya (0–4) | 1.37 (1.0) | 1.40 (1.1) | .05 | .819 | |

| Days previous week (0–7) | 1.77 (2.4) | 1.70 (2.4) | .13 | .722 | |

| Vegetables: snacks | |||||

| Cups per daya (0–4) | 1.12 (1.3) | 1.01 (1.3) | 1.8 | .179 | |

| Days previous week (0–7) | 4.21 (2.3) | 4.26 (2.4) | .05 | .830 | |

| Water: meals | |||||

| 8-oz glasses (0–4) | 1.97 (1.1) | 1.97 (1.2) | 1.08 | .299 | |

| Days previous week (0–7) | 3.75 (2.5) | 4.02 (2.6) | 2.42 | .120 | |

| Water: with snacks and in between | |||||

| 8-oz glasses (0–4) | 1.82 (1.3) | 1.88 (1.2) | .02 | .880 | |

| Days previous week (0–7) | 2.85 (2.1) | 3.79 (2.2) | 14.84 | <.001 | |

| Sweetened beverages: meals | |||||

| Size per beverageb (0–4) | 1.37 (.9) | 1.75 (1.0) | 18.91 | <.001 | |

| Days previous week (0–7) | 3.17 (2.4) | 3.99 (2.4) | 11.45 | .001 | |

| Sweetened beverages: with snacks and in between | |||||

| Size per beverageb (0–4) | 1.57 (1.0) | 1.84 (1.1) | 6.78 | .009 | |

| Days previous week (0–7) | 2.98 (2.0) | 3.60 (2.0) | 8.11 | .005 | |

| Packaged processed snacks | |||||

| Size per snackc (1–3) | 1.52 (.5) | 1.63 (.6) | 3.29 | .07 | |

| Days previous week (0–7) | 1.66 (1.7) | 1.76 (1.8) | .00 | .973 | |

| Usual item sized (1–4) | 1.84 (.7) | 2.03 (.8) | 9.65 | .002 | |

| Fast food restaurants | |||||

| Value/combo meale (1–4) | 1.13 (.8) | 1.32 (.9) | 6.07 | .014 | |

| Healthier optione (1–4) | 1.46 (.9) | 1.42 (.9) | .11 | .745 | |

| Physical Activity | |||||

| Days previous week (0–7) | 3.34 (2.1) | 2.79 (2.1) | 15.81 | <.001 | |

| Purposely walking instead of public transportation | |||||

| Speedf (0–3) | 1.62 (.8) | 1.45 (.9) | 5.35 | .021 | |

| Walking for exercise | Days previous week (0–7) | 2.92 (2.6) | 2.56 (2.6) | 4.07 | .044 |

| Days previous week (0–7) | 2.98 (2.7) | 2.28 (2.6) | 18.51 | <.001 | |

| Purposely taking stairs for exercise | |||||

| Flightsg (0–4) | 1.87 (1.5) | 1.53 (1.5) | 11.97 | .001 | |

| Leisure screen time | Days previous week (0–7) | 4.85 (1.8) | 5.51 (1.7) | 21.97 | <.001 |

pieces or cups: 0=0, 1=1/2, 2=1, 3=2, 4=>2

beverage sizes: 0=0, 1=<12oz, 2=12oz can, 3=20oz bottle, 4=>20oz

snack sizes: 1=smaller than 3/5×5inch index card, 2=about same size as index card, 3=larger than index card

fast food item size: 1=small, 2=medium, 3=large, 4=extra-large

how often make this choice: 0=never, 1=rarely, 2=sometimes, 3=always

walking speed: 0=don’t do this, 1=slow, 2=medium, 3=fast

flights: 0=0, 1=1, 2=2–3, 3=4–5, 4=6+

Results based on Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) with group (control/intervention) as a fixed factor and pre-test scores as covariate

Content validity was established with a panel of nutrition, physical activity, and measurement experts who reviewed the instrument. The instrument was then extensively pilot-tested in schools with similar youth and cognitive interviewing was used to improve clarity and understanding. The final instrument included photographs to improve estimation of serving sizes.

The behavioral instrument was also tested for reliability and validity. Through psychometric analyses, items with ceiling effects or low item-to-total correlations were dropped and inappropriate response options were modified. The Cronbach alpha coefficients for the final instrument ranged from 0.70 to 0.88. Test-retest (n=27, similar age and ethnicity) results showed correlations ranging from 0.30 to 0.80 for the behaviors, with most being between 0.40 to 0.60. To establish concurrent validity, the modified instrument was calibrated with the original Block instrument with correlations ranging from 0.52 to 0.88 for EW behaviors over the previous week. When the EW survey was compared to 24-hour recalls (mean of two days) in a separate sample (n=60, similar age and ethnicity) the percent of subjects with agreement within one standard deviation ranged from 60% to 75% for each behavior, except water where agreement was 54%. Correlations ranged from 0.30 to 0.60.

Theory-based psychosocial mediators

An instrument was developed for the theory-based potential psychosocial mediators from a review of relevant research studies and existing instruments. Content validity was established by a panel of nutrition education and measurement experts who reviewed the instrument. It was then pilot-tested along with the EW as described above. The measures are summarized here and scoring details are shown in the footnotes on Table 3. Scales were developed to measure outcome expectations or beliefs, intentionality, perceived barriers, and self-efficacy for each of the targeted behaviors, such as eating fruits and vegetables or drinking sweetened drinks. Each of these scales generally consisted of five to seven items. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scales were 0.50–0.75 for outcome expectations, 0.73–0.80 for perceived barriers, and 0.73–0.83 for self-efficacy, except for eating at fast food restaurants, which was 0.65.

Table 3.

Impact of Choice, Control & Change (C3) program on potential theory mediators of behavior change

| Scale (Score range)a |

Scale (Number of items per scale) |

Adjusted Post Mean (SD) |

Fe | pe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n=445) |

Control (n=417) |

||||

| Outcome Expectations (1–5)c | Drinking lots of sweetened beverages (8) | 3.49 (.65) | 3.26 (.61) | 27.96 | <.001 |

| Eating frequently at fast food restaurants (7) | 3.69 (.68) | 3.48 (.67) | 19.04 | <.001 | |

| Eating lots of packaged snacks (7 | 3.67 (.66) | 3.42 (.63) | 23.96 | <.001 | |

| Drinking plenty of water (8) | 3.92 (.68) | 3.76 (.76) | 11.42 | .001 | |

| Eating lots of fruit and vegetables (9) | 3.96 (.69) | 3.79 (.72) | 12.68 | <.001 | |

| Walking (7) | 4.05 (.70) | 3.89 (.70) | 12.15 | .001 | |

| Intention to Change (1–5)b | Total for the C3 obesity risk reducing behaviors (7) | 3.48 (.84) | 3.23 (.84) | 18.48 | <.001 |

| Drinking less soda and other sweetened beverages | 2.97 (1.24) | 2.70 (1.26) | 9.49 | .002 | |

| Eat less frequently at fast food restaurants | 3.07 (1.27) | 2.75 (1.29) | 11.48 | .001 | |

| Eat fewer packaged snacks | 3.03 (1.23) | 2.76 (1.23) | 9.36 | .002 | |

| Drink more water | 4.0 (1.20) | 3.76 (1.30) | 3.93 | .048 | |

| Eat more fruit and vegetables | 3.56 (1.24) | 3.37 (1.32) | 4.88 | .027 | |

| Do more physical activity | 3.82 (1.13) | 3.61 (1.26) | 6.36 | .012 | |

| Walk more | 3.91 (1.20) | 3.65 (1.26) | 6.08 | .014 | |

| Perceived Barriers (1–5)c | Eating healthfully (9) | 3.38 (.87) | 3.29 (.80) | .87 | .351 |

| Being physically active | 3.80 (1.0) | 3.58 (1.05) | 4.23 | .040 | |

| Self-Efficacy (1–4)d | Drinking less sweetened beverages (6) | 2.72 (.72) | 2.51 (.77) | 12.91 | <.001 |

| Eating less at the fast food restaurants (5) | 2.71 (.78) | 2.56 (.79) | 5.19 | .023 | |

| Eating fewer packaged snacks (6) | 2.74 (.85) | 2.59 (.85) | 4.68 | .031 | |

| Drinking lots of water (5) | 2.96 (.83) | 2.82 (.92) | 4.34 | .038 | |

| Eating fruit and vegetables (6) | 2.72 (.88) | 2.66 (.92) | 1.61 | .205 | |

| Walking and taking stairs (9) | 2.89 (.77) | 2.60 (.81) | 17.60 | <.001 | |

| Personal agency / Autonomous motivation (1–4)d | Eating (11) | 2.95 (.74) | 2.75 (.75) | 13.56 | <.001 |

| Competence (5) | 2.95 (.80) | 2.75 (.81) | 10.75 | .001 | |

| Autonomy (6) | 2.95 (.76) | 2.75 (.76) | 12.38 | .001 | |

| Physical activities (11) | 3.12 (.72) | 2.95 (.82) | 8.63 | .003 | |

| Competence (5) | 3.13 (.77) | 2.95 (.88) | 8.03 | .005 | |

| Autonomy (6) | 3.13 (.74) | 2.94 (.82) | 7.99 | .005 | |

Higher scores indicate more desirable beliefs

Intention to change: 1 = won’t do it within next 6 months, 2 = will try within the next 6 months, 3 = plan to do it in a month or so, 4 = currently doing it for past 1–6 months, 5 = have been doing it for over past 6 months

5-point response options: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = uncertain, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree

4-pont response options: 1 = not sure, 2 = a little sure, 3 = somewhat sure, 4 = very sure

Results based on Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) with group (control/intervention) as a fixed factor and pre-test scores as covariate

Personal agency has been found to be correlated with autonomous motivation (37). Thus, in contrast to self-efficacy, which was measured for each of the specific behaviors, personal agency, for which there were no prior diet-related measures, was measured using two general scales related to autonomous motivation– one for food choice and one for physical activity. These scales measured autonomy and competence and were based on those used in related studies (33,34). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient values ranged from 0.79 to 0.94. Relatedness to others from SDT was not measured.

Outcome evaluation data collection procedures

Trained research staff administered the instruments to all classes at the schools, reading all instructions to students following a standardized protocol: 562 students in intervention classes, and 574 student in the comparison classes, 417 to 460, depending on condition and instrument, completed both pre and post tests, due to absenteeism or students being pulled out for special services. Students whose parents denied consent (11 out of 1136, 1%) quietly read. Students who did not complete the survey did not differ from those who did in age, gender, or ethnicity. Nor were they clustered in particular classes. The surveys took two class periods to complete (about 90 minutes).

Outcome evaluation data analysis

For analyses, all items were coded so that the higher scores indicted selection of healthier options. Only students present at both pretest and posttest were included in the analyses. To compare means of intervention and control groups, Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was performed. Behavioral and mediating variables were set as dependent variables, and group (intervention or control) condition was used as a fixed factor. Pre-test scores were controlled for by including them in the model as covariates. Demographics were very homogenous across schools (that is, age, ethnicity, income levels determined by percent free or reduced lunch) and hence were not used as covariates. Even though the unit of randomization was school, the school sample size was too small to run multi-level analyses. For hypothesis testing, the criterion for statistical significance was set at p<.05. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 17 for Windows, released 23 August, 2008. SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, 2006) was used for data analyses.

RESULTS

The impact of the C3 intervention on behavioral outcomes is shown in Table 2. Intervention students reported a significant decrease in the less healthful behaviors compared to controls. They drank sweetened beverages significantly less often at meals, snacks, and between meals, and had smaller sizes each time. They ate significantly fewer packaged, processed snacks and had smaller sizes each time. Although they did not reduce the frequency of eating at fast food restaurants, intervention students reported ordering significantly smaller sizes and ordering value or combo meals less often, the last being driven by significant changes in boys only. Students did not report selecting healthier options. The students in the intervention group did not, however, report any significant improvements in fruit, vegetable or water intake; indeed the comparison group had higher intakes of fruit at the end of the intervention period. In terms of physical activity, students receiving the intervention intentionally walked and took the stairs for exercise more often and walked rather than take public transportation (the last driven by significant changes in boys only). Students in the intervention group, compared to controls, also decreased frequency of recreational screen-time. Effect sizes, where significant changes occurred, were 0.20 to 0.30.

The impact of the intervention on potential psychosocial mediating variables is shown in Table 3. Positive outcome expectations increased significantly for all seven C3 behaviors. Students in intervention schools also reported greater goal intention to change for all seven behaviors. The intervention group also reported increased self-efficacy for all targeted behaviors except eating more fruits and vegetables. The intervention students reported a reduced perception of barriers (higher scores indicate decreased perception of barriers) related to being physically active but not eating healthfully. Lastly, the intervention students felt a higher degree of personal agency or autonomous motivation in making healthful food choices and being physically active, reported as an improved sense of competence and autonomy.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of a science and nutrition education middle school curriculum, C3, on behaviors related to energy balance and potential psychosocial mediators of behavior change. The intervention focused on enhancing personal agency and autonomous motivation through science inquiry-based investigations to increase motivation coupled with self-regulation skills from behavior theory. This intervention resulted in decreases in frequency of consumption and size of sweetened beverages and packaged snacks, in size of items chosen at fast food restaurants, and in leisure screen time and increases in purposefully walking and taking the stairs for exercise but had no impact on fruit and vegetable or water intake.

The finding that the curriculum had mixed impacts on the targeted behaviors is similar to that of other obesity prevention intervention studies with middle school youth. For example, a study involving one computer-tailored session in school accompanied by a compact disc for parents, found no impacts on fruit, soft drinks, or water intakes and decreases in fat intake only in girls who had parental support (22,23). A study with students involving curriculum and additional healthy food options available at school lunch had a long term impact on preventing unfavorable increases in measures of body composition and on consumption of sweetened drinks but not on the other targeted behaviors of consumption of snacks or active commuting to school (20,21). An intervention focusing on goal-setting found positive impacts on composite scores created for dietary behaviors and physical activity behaviors, and on physical activity self-efficacy but only in those who set and adhered to their specific goals (49).

The generally positive behavioral results on reducing intakes of high calorie, low nutrient dense foods obtained in this study may be due to the intensity and duration of the intervention and the use of active student participation through science experiments. This explanation is strengthened by the finding that two other studies using intensive biology classes found improvements on body weight and related parameters (20,21). Students in the present study spent considerable time analyzing their own eating and physical activity patterns and comparing them to recommendations, a process that has been shown to increase sense of concern and hence motivation (52,53). Through experiments, students developed an in-depth understanding of the rationale for taking action, a strategy suggested as important by self-determination theory. They examined television advertisements and what was available in local grocery stores in order to reduce guilt by avoiding “person blame” and to empower students to understand and take action in an obesigenic environment. The use of a guided goal-setting process is likely to have enhanced cognitive self-regulation skills as reflected in improved competence scores.

The differential results on behavioral outcomes may also be due to the fact that the curriculum spent more time on behaviors related to energy balance and diabetes and that the activities students engaged in were more memorable than for behaviors related to fruits and vegetables, and water. For example, students explored the amount of sugar and fat in their favorite sweetened beverages, packaged processed snacks, and fast food items. They burned peanuts and other foods to learn about the calories in them. Students also found pedometers very motivating. Improving intakes of fruits and vegetables, particularly vegetables, has been shown to be difficult and even when effective with younger children, interventions tend not to be effective with adolescents (54, 55).

The intervention had significant positive effects on most of the potential psychosocial mediators measured, including two that a recent review found were most predictive of behavior change: outcome expectations and self-efficacy (53). Many studies have had mixed results and researchers have suggested that either the psychosocial mediators used in the studies were not appropriate or that the strategies used were ineffective (56,57).

In this study, the related overarching constructs of personal agency and autonomous motivation may serve as useful mediators of targeted behaviors as shown by the finding that those in the intervention group compared to controls significantly increased their sense of autonomy to take control and make good decisions about food and physical activity choices and in their sense of competence in being able to set goals and carry through with them. The novel combination of science inquiry methods and behavioral theory may provide strategies that are effective.

The study has many strengths. The intervention was conducted with an underserved, low-income youth population, where obesity and diabetes are highly prevalent in their families and communities. This content provided a meaningful rationale for taking action, which would encourage autonomous motivation according to SDT. The intervention focused on behaviors over which youth had some control, and used a clear conceptual framework, an innovative approach, and educational strategies directly linked to theory mediators. The hands-on activities were key for triggering behavioral change. In addition, the cluster randomization design resulted in two groups that were almost identical on all parameters measured, such as ethnicity, percent free and reduced price lunch, class size, attendance, reading and math scores, teacher absences, and percent experienced teachers. School meal menus and vending policies were also identical in the schools. This adds confidence in the results.

The study has some limitations. The fact that the behavioral data were self-reported is a limitation. However, the finding that some reported behaviors changed significantly while others did not reduces social desirability response bias as the sole explanation of the results. In the validation study, the correlation of the modified food frequency questionnaire with the original was high. Its correlation with 24-hour recalls was moderate but in the same range as found in validation studies for similar instruments with similar age groups (58,59). In addition, correlations between different methods are usually only moderate (60). Food frequency instruments are not always accurate for estimating absolute intakes of foods (60). However, it is not the absolute intake of the targeted foods that is of focus here, but the comparison between groups and between pre and post intervention using the same instrument. Nevertheless, the results should be interpreted with caution.

CONCLUSIONS AND APPLICATIONS

An intervention that focused on encouraging personal agency and autonomous motivation for healthful food and activity choices through the use of science inquiry processes coupled with self-regulation skills from behavior theory resulted in significant reductions in many targeted energy balance related behaviors. Future studies should include some measure of weight status as an outcome. Future studies should also aim to provide environmental supports for action, perhaps building on the requirement for wellness policies in schools (61,62).

It is encouraging that youth appear to be responsive to an approach that helps them understand that they have choices, can exert control, and can make changes in their own eating and physical activity behaviors as well as their personal food environments to enhance their health and help their bodies do what they want them to do. The fact that the curriculum was taught by teachers as opposed to researchers in required science classes suggests that such an approach can be disseminated for use by teachers. Nutrition educators can also apply such an approach in their work with middle school age children in a variety of other settings.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Isobel R. Contento, Email: irc6@columbia.edu, Program in Nutrition, Box 137, Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Teachers College, Columbia University, 525 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, Tel (212) 678-3949, Fax (212) 678-8259.

Pamela A. Koch, Email: pak14@columbia.edu, Program in Nutrition, Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Teachers College, Columbia University, 525 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, Tel (212) 678-3001, Fax (212) 678-8259.

Heewon Lee, Email: heewon11@hotmail.com, Program in Nutrition, Department of Health and Behavior Studies, Teachers College, Columbia University, 525 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, Tel (212) 678-3480, Fax (212) 678-8259.

A Calabrese-Barton, Email: acb@msu.edu, Department of Teacher Education, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, Tel (517) 432-4876, Fax (517) 432-2795.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sebastian RS, Wilkinson Enns C, Goldman JD. US adolescents and MyPyramid: associations between fast-food consumption and lower likelihood of meeting recommendations. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson RA, Bremer AA. Insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in the pediatric population. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2010;8:1–14. doi: 10.1089/met.2009.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan GE, Li SM, Zhou XH. Prevalence and trends of a metabolic syndrome phenotype among U.S. Adolescents, 1999–2000. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2438–2443. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorof JM, Lai D, Turner J, Poffenbarger T, Portman RJ. Overweight, ethnicity, and the prevalence of hypertension in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):475–482. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jago R, Harrell JS, McMurray RG, Edelstein S, El Ghormli L, Bassin S. Prevalence of abnormal lipid and blood pressure values among an ethnically diverse population of eighth-grade adolescents and screening implications. Pediatrics. 2006;117:2065–2073. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorpe LE, List DG, Marx T, May L, Helgerson SD, Frieden TR. Childhood obesity in New York City elementary school students. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1496–1500. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The surgeon general's vision for a healthy and fit nation. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.White house task force on childhood obesity. Solving the problem of childhood obesity within one generation. White house task force on childhood obesity. Domestic Policy Council. Washington, DC: 2010 doi: 10.1089/bfm.2010.9980. www.letsmove.gov/taskforce_childhoodobesityrpt.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Doak CM, Visscher TL, Renders CM, Seidell JC. The prevention of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a review of interventions and programmes. Obes Rev. 2006;7:111–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flynn MA, McNeil DA, Maloff B, et al. Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: a synthesis of evidence with 'best practice' recommendations. Obes Rev. 2006;7 Suppl1:7–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Summerbell CD, Waters E, Edmunds LD, Kelly S, Brown T, Campbell KJ. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub2. CD001871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaya FT, Flores D, Gbarayor CM, Wang J. School-based obesity interventions: a literature review. J Sch Health. 2008;78:189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz DL, O'Connell M, Njike VY, Yeh MC, Nawaz H. Strategies for the prevention and control of obesity in the school setting: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1780–1789. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez-Suarez C, Worley A, Grimmer-Somers K, Dones V. School-based interventions on childhood obesity: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zensen W, Kridli S. Integrative review of school-based childhood obesity prevention programs. J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23:242–258. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wardle J, Brodersen NH, Boniface D. School-based physical activity and changes in adiposity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1464–1468. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robinson TN. Reducing children's television viewing to prevent obesity: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1561–1567. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson TN, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, et al. Dance and reducing television viewing to prevent weight gain in African-American girls: the Stanford GEMS pilot study. Ethn Dis. Winter. 2003;13(1) Suppl 1:S65–S77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, et al. Reducing obesity via a school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:409–418. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh AS, Chin A, Paw MJ, Brug J, van Mechelen W. Short-term effects of school-based weight gain prevention among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:565–571. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.6.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh AS, Chin A, Paw MJ, Brug J, van Mechelen W. Dutch obesity intervention in teenagers: effectiveness of a school-based program on body composition and behavior. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:309–317. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haerens L, Deforche B, Maes L, Stevens V, Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Body mass effects of a physical activity and healthy food intervention in middle schools. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:847–854. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haerens L, Deforche B, Maes L, Cardon G, Stevens V, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Evaluation of a 2-year physical activity and healthy eating intervention in middle school children. Health Educ Res. 2006;21:911–921. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haerens L, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Maes L, Vereecken C, Brug J, Deforche B. The effects of a middle-school healthy eating intervention on adolescents' fat and fruit intake and soft drinks consumption. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:443–449. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007219652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenbaum M, Nonas C, Weil R, et al. School-based intervention acutely improves insulin sensitivity and decreases inflammatory markers and body fatness in junior high school students. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:504–508. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: Social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol. 1989;44:1175–1184. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.44.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deci EL, Ryan RM. "what" and "why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry. 2000;11:227–268. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deci EL, Ryan RM. Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life's domains. Canadian Psychology. 2008;49:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fortier MS, Sweet SN, O'Sullivan TL, Williams GC. A self-determination process model of physical activity adoption in the context of randomized controlled trial. Psychol Sport Ex. 2007;8:741–757. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webber KH, Tate DE, Ward DS, Bowling JM. Motivation and its relationship to adherence to self-monitoring and weight loss in a 16-week internet behavioral weight loss intervention. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gillison FB, Standage M, Skevington SM. Relationships among adolescents' weight perceptions, exercise goals, exercise motivation, quality of life and leisure-time exercise behaviour: a self-determination theory approach. Health Educ Res. 2006;21:836–847. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Standage M, Sebire SJ, Loney T. Does exercise motivation predict engagement in objectively assessed bouts of moderate-intensity exercise? A self-determination theory perspective. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2008;30:337–352. doi: 10.1123/jsep.30.4.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Standage M, Duda JL, Ntoumanis N. A test of self-determination theory in school physical education. Br J Educ Psychol. 2005;75(Pt 3):411–433. doi: 10.1348/000709904X22359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kremers SP, de Bruijn GJ, Visscher TL, van Mechelen W, de Vries NK, Brug J. Environmental influences on energy balance-related behaviors: a dual-process view. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNeill LH, Wyrwich KW, Brownson RC, Clark EM, Kreuter MW. Individual, social environmental, and physical environmental influences on physical activity among black and white adults: a structural equation analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31:36–44. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3101_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120 Suppl 4:S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peters JC, Wyatt HR, Donahoo WT, Hill JO. From instinct to intellect: the challenge of maintaining healthy weight in the modern world. Obes Rev. 2002;3:69–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2002.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Institute of Medicine. Food marketing to children: Threat or opportunity? Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koch PA, Calabrese Barton A, Whitaker RC, Contento I. Choice, Control, and Change: Using scientific evidence to promote healthful food and activity choices. Science Scope. 2007 November;:16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Contento IR, Michela JL. Nutrition and food choice behavior among children and adolescents. In: Goreczny AJ, Hersen M, editors. Handbook of pediatric and adolescent health psychology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1998. pp. 249–273. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flavell JH. Cognitive development. Fourth edition. Inglewood-Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baranowski T, Cerin E, Baranowski J. Steps in the design, development and formative evaluation of obesity prevention-related behavior change trials. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Contento IR. Nutrition education: Linking research, theory, and practice. Second edition. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Committee on Science Education Standards and Assessment. Center for Science, Mathematics, and Engineering Education, National Research Council. National Science Education Standards. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shilts MK, Horowitz M, Townsend MS. Guided goal setting: effectiveness in a dietary and physical activity intervention with low-income adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2009;21:111–122. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2009.21.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Contento IR, Koch PA, Lee H, Sauberli W, Calabrese-Barton A. Enhancing personal agency and competence in eating and moving: formative evaluation of a middle school curriculum--Choice, Control, and Change. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(5 Suppl):S179–S186. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Block G, Murphy M, Roulet JB, Wakimoto P, Crawford PB, Block T. Pilot validation of a FFQ for children 8–10 years. Proceedings of Fourth International Conference on Dietary Assessment Methods; Arizona. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Contento I, Balch GI, Bronner YL, et al. The effectiveness of nutrition education and implications for nutrition education policy, programs, and research: A review of research. J Nutr Educ. 1995;27:279–418. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cerin E, Barnett A, Baranowski T. Testing theories of behavior change in youth using the mediating variables model with intervention programs. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41:309–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.03.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lytle LA, Murray DM, Perry CL, et al. School-based approaches to affect adolescents' diets: results from the TEENS study. Health Educ Behav. 2004 Apr;31(2):270–287. doi: 10.1177/1090198103260635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stables GJ, Young EM, Howerton MW, et al. Small school-based effectiveness trials increase vegetable and fruit consumption among youth. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chin A, Paw MJ, Singh AS, Brug J, van Mechelen W. Why did soft drink consumption decrease but screen time not? Mediating mechanisms in a school-based obesity prevention program. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:41. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haerens L, Cerin E, Deforche B, Maes L, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Explaining the effects of a 1-year intervention promoting a low fat diet in adolescent girls: a mediation analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:55. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hoelscher DM, Day S, Kelder SH, Ward JI. Reproducibility and validity of the secondary level school-based nutrition monitoring student questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003:186–194. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thiagarajah K, Fly AD, Hoelscher DM, et al. Validating the food behavior questions from the elementary school SPAN questionnaire. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008;40:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Willett W. Nutritional epidemiology. Oxford University Press: NY; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 61.United States Congress. Local Wellness Policy. Section 204 of Public Law 108–265, Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004. Congressional Record. 2004 June 30;Vol. 150

- 62.Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O'Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:253–272. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]