Abstract

The authors tested the following risk model for disordered eating in late elementary school-age boys: Pubertal status is associated with increases in negative urgency, i.e., the tendency to act rashly when distressed; high levels of negative urgency then influence binge eating through psychosocial learning; and binge eating influences purging. A sample of 908 fifth grade boys completed questionnaire measures of puberty, negative urgency, dieting/thinness and eating expectancies, and eating pathology. Eating disorder symptoms were present in these young boys: 10% reported binge eating and 4.2% reported purging through self-induced vomiting. Each hypothesis in the risk model was supported. Boys this young do in fact engage in the maladaptive behaviors of binge eating and purging; it is crucial to develop explanatory risk models for this group. To this end, it appears that characteristics of boys, including their pubertal status, personalities, and psychosocial learning help identify boys at risk.

Keywords: eating disorders, youth, young boys, risk factors, puberty

Researchers know very little about binge eating and purging in late elementary school-age boys (Keel, Fulkerson, & Leon, 1997; McCabe & Vincent, 2003). Perhaps because boys engage in disordered eating behaviors at a lower rate than girls (Cotrufo, Cella, Cremato, & Labella, 2007; Leon, Fulkerson, Perry, & Early-Zald, 1995; McCabe & Vincent, 2003), there have been fewer investigations into the process by which boys develop these behaviors. This paper introduces a model of risk for binge eating and purging that applies to boys and reports on a cross-sectional test of the model in a sample of 908 5th grade boys. The model integrates pubertal onset, personality, and psychosocial learning processes to concurrently predict binge eater status and purger status in this sample of boys. Following a brief review of the existing literature on eating disordered behaviors in young boys, we introduce our model, its basis in the literature, and our empirical test of it.

Young Boys and Eating Disordered Behavior

In order to study boys very early in a possible risk process, we focused on boys in their last year of elementary school (5th grade). Some of them had experienced the onset of puberty, but none were yet in middle school. The frequencies of binge eating and purging in boys prior to middle school are not known. There is evidence that 25% of 14 year old boys1 in an Australian study reported having at least occasionally engaged in one or more extreme methods of weight loss (Maude, Wertheim, Paxton, Gibbons, & Szmukler, 1993), and in other Australian and U.S. samples, approximately 33% of adolescent boys report wanting a leaner body (Drewnowski & Yee, 1987; McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2001). Thus, there is some evidence of eating disordered behaviors and cognitions in adolescent boys.

A Risk Model for Binge Eating and Purging in Late Elementary School-Age Boys

Common risk factors for boys and girls?

One important question is whether risk factors identified in girls are also operative in boys. In the few studies that have directly compared risk factors across gender, findings have suggested they may be. Scores on numerous measures of risk and symptom expression have proved invariant across gender (Boerner, Spillane, Anderson, & Smith, 2004; Spillane, Boener, Anderson, & Smith, 2004). Importantly, correlations among risk factors, and between risk factors and symptom reports, were also invariant across gender (Boerner et al., 2004; Spillane et al., 2004). Although these studies do not pertain to children as young as those in the current study, the findings do suggest the value of investigating similar risk factors for both sexes. Thus, we propose that a risk model recently developed for girls (Combs & Smith, 2009) and recently validated on late elementary school-age girls (Combs, Pearson, & Smith, in press-a) applies to young boys as well. The model includes an integration of puberty, personality and psychosocial learning influences on risk. We next present each component of the model, the integrated model, and the hypotheses for the current study.2

Puberty: Past inconsistent findings and a proposed mechanism of influence

Some studies have failed to find an association between pubertal onset and increased risk for eating disordered behavior in boys (Keel et al., 1997; Leon et al., 1995; McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2003). Some authors, noting that puberty in boys is associated with weight gain and an increase in lean muscle mass, have suggested that pubertal changes tend to bring boys' bodies closer to the socially reinforced ideal (McCabe & Vincent, 2003), with the implication that puberty may provide a protective function (Cotrufo et al. 2007; Decastro & Goldstein, 1995).

However, pubertal development has been found to predict subsequent problem eating in adolescent boys (Leon, Fulkerson, Perry, Keel, & Klump, 1999) and cross-sectional research has found that both purging rates and attempts to lose weight were positively associated with pubertal development (Field, Camargo, Taylor, Berkey, Frazier, Gillman, & Colditz, 1999; O'Dea & Abraham, 1999). Thus, puberty may be associated with increased risk in boys.

Consistent with this possibility, pubertal onset is associated with increased levels of emotional volatility and negative affect (Allen & Matthews, 1997; Spear, 2000), and also with an increase in rash or impulsive action undertaken when emotional (Luna & Sweeney, 2004; Steinberg, 2004). This change can be understood to reflect a pubertal-based increase in the personality trait of negative urgency, which is the tendency to act rashly when distressed (Cyders & Smith, 2008; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). We believe that this developmental increase in negative urgency increases eating disorder risk, through a mechanism we will describe below.

Personality risk: negative urgency

A recent meta-analysis comparing different personality dispositions to rash action found that negative urgency was related concurrently to bulimia nervosa symptoms in women (r = .40): all other impulsivity-related traits had very minimal relations with symptom levels (Fischer, Smith, & Cyders, 2008), as does global negative affect (Keel, Klump, Leon, & Fulkerson, 1998; Stice, 2002). Change in negative urgency levels is associated with change in bulimia nervosa symptoms (Anestis, Selby, & Joiner, 2007), and negative urgency at the start of college interacted with being a victim of sexual assault to predict subsequent bulimia nervosa symptoms (Fischer, Stojek, & Collins, 2009). In elementary school-age girls, negative urgency concurrently predicts both binge eating and purging behavior (Combs et al., in press-a). We thus anticipated that negative urgency would also concurrently predict binge eating and purging behavior in 5th grade boys.

Psychosocial learning risk: Expectancies for reinforcement from eating and from dieting/thinness

Expectancies are learned anticipations of the likely consequences of behavioral choices. They are understood to represent summaries of individuals' learning histories, and are formed based on the multitude of direct and vicarious learning experiences that individuals undergo. The expectancies one forms then influence one's future behavioral choices: one tends to choose behaviors from which one expects rewards and avoid behaviors for which one expects punishment.

Individual differences in the expectancy that eating helps one manage negative mood states and individual differences in the expectancy for overgeneralized life improvement from dieting and thinness predicted the onset of both binge eating and purging in adolescent girls (Combs, Smith, Flory, Simmons, & Hill, in press-b; Smith, Simmons, Flory, Annus, & Hill, 2007). Manipulation of dieting/thinness expectancies reduced eating disorder symptoms in college women and high school girls (Annus, Smith, & Masters, 2008). It thus appears that expectancies may play a causal role in eating disorder symptoms for women. Boerner et al. (2004) found similar associations between expectancies and symptomatology in adolescent boys. Therefore, we anticipated that both types of expectancies would be associated with binge eating and purging in 5th grade boys.

Although many past studies have documented linear relations between dieting/thinness expectancies and symptom reports (Holhstein, Smith, & Atlas, 1998; Simmons, Smith, & Hill, 2002; Smith et al., 2007; Stice & Whitenton, 2002), Combs et al. (in press-a, in press-b) demonstrated that the relationship between dieting/thinness expectancies and symptoms consists of a combination of linear and quadratic trends: variation in low and moderate levels of dieting/thinness expectancy endorsement are unrelated to symptom levels, but variation within high levels of expectancy endorsement are strongly associated with symptom reports. It appears that only relatively extreme endorsement of expectancies for life improvement from dieting/thinness is associated with dysfunction; moderate endorsement of such expectancies may reflect an accurate perception of reality. We believe the same will be true among 5th grade boys.

Integrating personality and psychosocial learning: the Acquired Preparedness (AP) model of eating disorder risk extended

In general, AP models hold that individual differences in personality contribute to individual differences in learning: specifically, as a function of individual differences in personality, individuals vary in the experiences to which they expose themselves, how they react to those experiences, and what they learn from the experiences (Caspi, 1993; Caspi & Roberts, 2001; Combs et al., in press-a, in press-b; Cyders & Smith, 2008; Settles, Cyders, & Smith, in press; Smith & Anderson, 2001; Smith, Williams, Cyders, & Kelley, 2006).

Applied to eating disorders, the AP model is as follows (Combs & Smith, 2009). Boys high in negative urgency are disposed to act rashly when experiencing distress. Many rash actions, including binge eating, tend to provide relief from distress through both the reinforcement they provide (Agras & Telch, 1998) and through distraction from the original distress (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991). In fact, males often report feeling happy after a binge (Leon, Carroll, Chernyk, & Finn, 1985). Thus, the binge eating is reinforced, and, over time, high-urgency boys develop expectancies that binge eating provides the reward of distress relief. This expectancy, in turn, increases the likelihood of future binge eating. The term acquired preparedness refers to the concept that, as a function of individual differences in personality, individuals are differentially prepared to acquire high risk expectancies.

The risk model includes two other components in addition to the AP process. First, many boys do wish for leaner bodies (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2001). Accordingly, purging behavior in 5th grade boys should be predictable from binge eating and from expectancies for reinforcement from dieting and thinness. Purging behavior is predictable from binge eating because one is most likely to purge when one has ingested excessive amounts of food, and purging is predictable from dieting/thinness expectancies because purging can be seen as a way to achieve or maintain thinness.

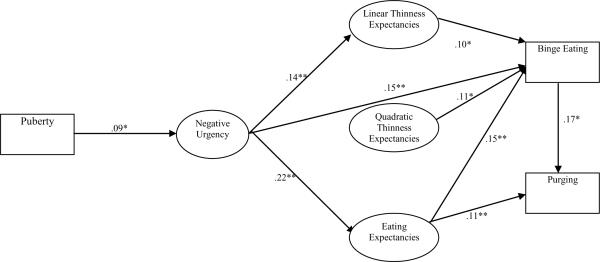

Second, we anticipated that pubertal status would increase the likelihood of binge eating and purging in this population. We propose that pubertal onset is associated with negative urgency, due to the increased emotionality and emotion-driven rash action characteristic of postpubertal individuals (Luna & Sweeney, 2004; Steinberg, 2004); hence, puberty indirectly leads to increases in eating expectancies, and thus binge eating and purging. Figure 1 presents a schematic of this risk model.

Figure 1.

Visual representation of the empirical test of the risk model. The arrows represent the significant tested pathways; the corresponding numbers refer to the maximum likelihood coefficient for each respective relationship. Variables represented in ovals are latent variables; variables represented in squares are measured variables. Relationships modeled but not visually represented are as follows: we did not include either error terms or disturbance terms, nor did we include correlations among the three expectancy measures. In the measurement model of dieting/thinness expectancies, each parcel for linear expectancies was allowed to correlate with its square, which was a parcel for quadratic expectancies. * p < .01; ** p < .001.

The model describes a temporal sequence of causal processes that increase risk for binge eating and purging behavior in young boys. The current study is a cross-sectional test of whether the associations specified in the model are present at one point in time: it serves as a first step toward evaluating the model. If the hypothesized associations are present, then longitudinal tests of the model are indicated. If the hypothesized associations are not present, there would be good reason to doubt the validity of the model.

Method

Participants

The participants in this study were 908 fifth grade boys assessed during the spring of their last year in elementary school. The mean age of the participants at the initiation of the study was 10.90 years. Most were Caucasian (62.76%), followed by African American (16.24%); the remainder of the sample identified themselves as Hispanic (7.42%), Asian (2.09%), Arabic (0.72%), or other (10.79%).

Measures

Demographic and Background Questionnaire

This measure provided the assessment of the demographic information reported above.

The Pubertal Development Scale (PDS: Petersen et al., 1988)

This scale consists of five questions for boys and five questions for girls. Sample questions are, for boys, “do you have facial hair yet?” and, for girls, “have you begun to have your period?” Individuals respond on a 4 point scale. The scale has acceptable reliability estimates (α's ranging from .67 to .76 for 11 year olds), and scores on it correlate highly with physician ratings and other forms of self-report (r values ranging from .61 to .67: Brooks-Gunn et al., 1987; Coleman & Coleman, 2002). The PDS permits dichotomous classifications as pre- pubertal or pubertal, with mean scores above 2.5 indicative of pubertal onset. As is common (e.g., Culbert, Burt, McGue, Iacono, & Klump, 2009), we used the dichotomous classification in the current study.

Eating Expectancy Inventory (EEI; Hohlstein et al., 1998)

This five-factor measure reflects expectancies for reinforcement from eating. For this study, we used a measure of the expectancy that eating helps one manage negative mood states. Validity evidence for this scale was presented above: for example, it predicts subsequent onset of binge eating (Smith et al., 2007). In the current sample of boys, as in past samples of girls, the scale was internally consistent (α = .93).

Thinness and Restricting Expectancy Inventory (TREI; Hohlstein et al., 1998)

This measure reflects overgeneralized expectancies about the life benefits of dieting and thinness. Items include such statements as “I would feel like I could do whatever I wanted to if I were thin.” The scale has been shown to be unidimensional, correlated with eating disorder symptoms in adolescent and adult samples, and predictive of eating disorder symptom onset (Hohlstein et al., 1998; MacBrayer, Smith, McCarthy, Demos, & Simmons, 2001; Simmons et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2007). As in past samples with girls, the scale was internally consistent in this sample of boys (α = .91).

UPPS-P Negative Urgency Scale (Lynam, Smith, Cyders, Fischer, & Whiteside, 2007)

Negative urgency is related to bulimic symptom expression in late adolescents and adults (Fischer et al., 2008), and a child version of the negative urgency scale recently proved to be internally consistent (α = .87), have good convergent validity across assessment method, good discriminant validity from other impulsivity-related measures, and was predictive of criteria in theoretically consistent ways (Zapolski, Stairs, Settles, Combs, & Smith, 2010). In the current sample, the internal consistency of the scale was estimated as α = .84.

Eating Disorder Examination- Questionnaire (EDE-Q; Fairburn & Beglin, 1994)

The EDE-Q is a self-report version of the Eating Disorders Examination semi-structured interview (Cooper & Fairburn, 1993) designed to assess the full range of behavioral and cognitive or attitudinal features of the specific psychopathology of eating disorders during the preceding 4 weeks, including patients' extreme concerns about their shape and weight. The EDE-Q has been shown to have good reliability and validity (Cooper & Fairburn, 1993; Luce & Crowther, 1999; Mond, Hay, Rodgers, Owen, & Beumont, 2004). Carter, Stewart, and Fairburn (2001) modified the EDE-Q for use with children ages 12–14, by shortening the length of time referred to in the questions to the past two weeks and by using age-appropriate wording. We used their adapted version of the EDE-Q, and, following pilot research, we also defined concepts that could possibly be difficult to understand. Examples of changes from the adult version of the measure include changing the word “restrict” to “cut back on” and the word “influence” to “control,” and defining terms such as “laxatives”, “diuretics”, and “binge eating.” For purposes of comparison, we also used fairly stringent guidelines to define “binge eating” and “purge.” Binge eating was considered present if the participants reported having engaged in binge eating in response to two questions, the first asking for the frequency of loss of control binge eating during the past two weeks, and the second asking whether the participant had engaged in binge eating (after defining binge eating). Purging was considered present if the participants answered yes to the following question: “Over the past two weeks, have you made yourself sick (vomit) as a means of controlling your weight, or because you ate a lot?”

Procedure

Data collection

The questionnaires were administered in 23 public elementary schools during school hours. A passive consent procedure was used. Each family was sent a letter, through the U.S. Mail, introducing the study. Families were asked to return an enclosed, stamped letter or call a phone number if they did not want their child to participate. Out of 980 5th grade boys in the participating schools, 92.7%, or 908, of the boys participated in the study. A total of 72 boys did not participate due to one of the following reasons: families declined to participate, students declined assent, or a variety of other reasons, such as language disabilities that precluded completing the questionnaires. Questionnaires were administered in school classrooms. It was made clear to the students that their responses on the questionnaire were to be kept confidential and no one outside of the research team would see them. The procedure took 60 minutes or less and was approved by the University's IRB and the participating school systems.

Data Analytic Method

The aim of this investigation was to test a sequence of predictive relationships: puberty onset predicts higher levels of negative urgency and negative urgency predicts higher levels of eating expectancies. Both eating expectancies and dieting/thinness expectancies predict binge eater status, and binge eater status, in turn, predicts purger status. As noted above, we hypothesized a series of mediational relationships among these variables. We therefore adopted a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach. We constructed one primary structural model that included puberty, negative urgency, linear dieting/thinness expectancies, quadratic dieting/thinness expectancies, linear eating expectancies, binge eating, and purging.

We represented negative urgency and the expectancies as latent variables. We did so because, for each variable, we understand the indicators of the variable to be expressions of a common, underlying construct. Using latent variable theory (Bollen & Lennox, 1991; Borsboom, Mellenbergh, & van-Heerden, 2003), we view variability in indicator responses as effects of variability in the underlying construct. We modeled each latent variable using four parcels (or groups) of items as manifest indicators. We used parcels of items for the following reasons. First, the reliability of a parcel of items is greater than that of a single item, so parcels can serve as more stable indicators of a latent construct. Second, as combinations of items, parcels provide more scale points, thereby more closely approximating continuous measurement of the latent construct. Third, there is reduced risk of spuriously positive correlations, both because fewer correlations are being estimated and because each estimate is based on more stable indicators. These advantages have been described by Little, Cunningham, Shahar, and Widamon (2002). The crucial relevant caution about using parcels is that they could mask multidimensionality in an item set (Hagtvet & Nasser, 2004). Negative urgency and the two expectancy constructs have been shown to be unidimensional in independent, prior factor analyses (Cyders & Smith, 2007; Holhstein et al., 1998; MacBrayer et al., 2001; Zapolski, Cyders, & Smith, 2009), so that concern is significantly mitigated.

To measure quadratic thinness expectancies, we followed the approach recommended by Marsh, Wen, and Hau (2004) for constructing product terms in SEM models of latent variables; this approach was used by Combs et al. (in press-b). Specifically, we first centered all linear dieting/thinness expectancy parcel scores. We then squared each centered parcel, and each of the squared values became indicators of the quadratic expectancy variable. Thus, the indicators of linear expectancies were centered parcels 1, 2, 3 and 4: the indicators of quadratic expectancies were centered parcel 1 squared, centered parcel 2 squared, centered parcel 3 squared and centered parcel 4 squared. We centered the parcels to remove nonessential collinearity between the linear and quadratic variables (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003; Marsh et al., 2004); our squares of the parcels reflect Marsh et al.'s (2004) recommended matched pairs approach, and we included the quadratic term only together with the linear term, so the quadratic term was corrected for its overlap with the linear effect (Cohen et al., 2003).

We measured SEM model fit using four common indices: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Nonnormed Fit Index (NNFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Guidelines for these indices vary: CFI and NNFI values of .90 or .95 are described as representing good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005). RMSEA values of .06 are thought to indicate a close fit, .08 a fair fit, and .10 a marginal fit (Brown & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999), and SRMR values of approximately .09 tend to indicate good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Overall evaluation of model fit is made by considering the values of each of the four fit indices; models that fit well on most indices are generally considered well-fitting. We used MPlus (Muthén & Muthén, 2004) to run the analyses.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The sample showed a 10.0% rate of binge eating in boys. Among the boys who reported binge eating, the number of binges over the past two weeks ranged from a low of 1 to a high of 8; the mean was 2.32. The sample had a 4.2% rate of purging among boys; all those boys reported a single purging episode. In this sample, 24.0 % of boys reported themselves as having experienced pubertal onset (measured as an average item score of 2.5 on the PDS).

Correlations Among Pubertal Status, Negative Urgency, Eating Expectancies, Dieting/Thinness Expectancies, Binge Eater Status, and Purger Status

Table 1 presents correlations among the study variables. Because pubertal status, binge eater status, and purger status are dichotomous, correlations between those three variables are phi coefficients and correlations between any of those variables and other variables are point biserial correlations. Correlations among negative urgency and the expectancies are product moment correlations. As the table shows, pubertal onset is associated with increased negative urgency and increased quadratic dieting/thinness expectancies. Negative urgency is associated with higher levels of all expectancies, binge eating, and purging. Eating expectancies are associated with linear dieting/thinness expectancies, and there is an association between the linear and quadratic dieting/thinness expectancy scores. Binge eater status is related to purger status.

Table 1.

Correlations among the variables.

| Puberty | Urgency | LTE | QTE | EE | Binge | Purge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puberty | -- | ||||||

| Urgency | .08* | -- | |||||

| LTE | .05 | .13** | -- | ||||

| QTE | .12** | .03 | .38** | -- | |||

| EE | .01 | .20** | .27** | .04 | -- | ||

| Binge | .04 | .18** | .19** | .13** | .21** | -- | |

| Purge | .05 | .11** | .09** | .04 | .16** | .21** | -- |

NOTE: LTE = Linear Thinness Expectancies; QTE = Quadratic Thinness Expectancies, EE = Eating Expectancies

= significant at the p < .01 level

= significant at the p < .001 level.

Test of the Theoretical Model

Our model involved a risk process indicating relationships from puberty to negative urgency, negative urgency to eating expectancies, eating and dieting/thinness expectancies to binge eating and binge eating to purging; we also allowed the latent variables reflecting the expectancies to correlate with one another. We tested the following set of mediational pathways implied by our theory: (1) from puberty through negative urgency to eating expectancies; (2) from negative urgency through eating expectancies to binge eater status; (3) from negative urgency through binge eating to purger status; (4) from eating expectancies through binge eating to purger status; (5) from quadratic dieting/thinness expectancies through binge eating to purger status; and (6) from linear dieting/thinness expectancies through binge eating to purger status. In addition to these mediational pathways, we also allowed puberty to directly relate to all other variables, negative urgency to directly relate to binge eating and purging, and eating expectancies to relate directly to purging. We did so to allow for the possibility of effects not captured by our proposed mediational pathways. The model is depicted in Figure 1.

The structural model fit well, with a CFI of 0.98, a NNFI of 0.97, an RMSEA of 0.04 (90% confidence interval: .03 – .05), and an SRMR of 0.04. As anticipated, pubertal status was associated with higher levels of negative urgency. Negative urgency was associated with eating expectancies and linear dieting/thinness expectancies, but not with quadratic dieting/thinness expectancies (counter to our prediction). Linear dieting/thinness expectancies, quadratic dieting/thinness expectancies, and eating expectancies were associated with binge eating, and binge eating was associated with purging. Interestingly, negative urgency had a direct effect on binge eating, i.e., an effect not mediated by variables included in our model. And, eating expectancies had a direct, non-mediated effect on purging.

To confirm that the nature of the quadratic relationship between dieting/thinness expectancies and binge eating had the form we hypothesized, we conducted follow up tests. Among boys whose dieting/thinness expectancies were at the mean or below, there was no association between the expectancies and binge eating (r = −.02, p = .74). Among boys whose dieting/ thinness expectancies were above the mean, there was a significant association (r = .15, p < .001). Thus, just as was true among early adolescent and pre-adolescent girls (Combs et al., in press-a, in press-b), variation at the upper end of dieting/ thinness expectancy endorsement is what was associated with binge eating behavior in 5th grade boys.

To understand the magnitude of the associations in the model, we computed odds ratios for each predictor with binge eating and purging. For each one unit increase in negative urgency, boys were 2.04 times more likely to have engaged in binge eating. For each one unit increase in the linear component of dieting/thinness expectancies, boys were 1.31 times more likely to binge eat, and for each one unit increase in the quadratic component of these expectancies, boys were 1.12 times more likely to binge eat (but for boys whose dieting/thinness expectancy scores were in the predictive range, i.e. above the mean, the odds ratio for binge eating was 1.46). For each one unit increase in eating expectancies, boys were 1.33 times more like to binge eat and 1.40 times more likely to purge. Boys in the binge eating group were 4.96 times more likely to purge.

Tests of Mediational Pathways

We present the statistical tests of mediation for each of the five hypothesized mediational effects. First, statistical tests of mediation were consistent with the hypothesized mediational processes involving pubertal status and negative urgency: negative urgency appeared to mediate puberty's effect on eating expectancies (z = 2.26, p < .05, b = .02). Second, results were consistent with the AP hypothesis that eating expectancies mediate negative urgency's influence on binge eater status, (z = 3.53, p < .001, b = .03). Third, binge eater status appeared to mediate the influence of negative urgency on purger status (z = 3.23, p < .001, b = .03). Fourth, binge eater status also appeared to mediate the influence of eating expectancies on purger status (z = 3.24, p < .001, b = .03). Fifth, binge eater status appeared to mediate the influence of quadratic dieting/thinness expectancies on purger status (z = 2.38, p < .01, b = .02), and sixth, binge eater status appeared to mediate the influence of linear dieting/thinness expectancies on purger status (z = 2.27, p < .05, b = .02). Thus, the patterns of covariation in the data were consistent with each of the five mediational processes hypothesized in the model.

Discussion

In this large sample of 5th grade boys, there was evidence that some boys did in fact report binge eating and purging behavior. The finding that 10% (n = 91) of the boys reported having engaged in binge eating and 4.2% (n = 38) reported having purged (self-induced vomiting) is important: that some boys this young appear to be engaging in these maladaptive behaviors is a matter of clinical concern.

It is therefore important that researchers understand the correlates, and ultimately the causes, of these behaviors. The present study offered an attempt to move toward that goal. We conducted a cross-sectional test of a risk model used to explain eating disordered behavior in pre-adolescent girls (Combs et al., in press-a). The pattern of associations observed in this study was consistent with that model. Puberty was associated with higher levels of negative urgency. Negative urgency was associated with increased expectancies that eating helps one manage negative mood states, which in turn were associated with increased likelihood to binge, and thus purge. Statistical tests of mediation were consistent with the hypotheses that (a) the influence of puberty on eating expectancies appeared to have been indirect through negative urgency; (b) the influence of negative urgency on binge eating appeared to have been partially indirect, through eating expectancies; and (c) the influence of eating expectancies on purging behavior appeared to have been partially indirect, through binge eating. All three expectancies (linear thinness, quadratic thinness, and eating expectancies) predicted binge eating behavior in 5th grade boys.

This risk model proposes a mechanism by which pubertal onset increases risk: pubertal onset may increase levels of negative urgency, which has been shown to be associated with symptom level in late adolescents and adults (Fischer et al., 2008) and which may operate similarly in young boys. Second and relatedly, the model specifies a process by which negative urgency increases risk: boys high in negative urgency appear to be differentially prepared to acquire the high risk expectancy that eating helps one manage negative affect. This expectancy, in turn, is associated with symptom expression in these 5th grade boys, just as it is in girls of the same age (Combs et al., in press-a), early adolescent girls (Combs et al., in press-b; MacBrayer et al., 2001; Smith et al., 2007), late adolescent girls (Simmons et al., 2002), and adult women (Hohlstein et al., 1998). Thus, if puberty leads to higher levels of negative urgency, it may create a facilitative condition for high-risk learning among young boys, just as it appears to do among girls.

Third, it appears to be true for 5th grade boys, just as for girls, that dieting/thinness expectancies relate to symptom expression in a combination of linear and quadratic effects. For 5th grade boys falling at or below the mean on dieting/thinness expectancies, their expectancies did not predict whether they engaged in either binge eating or purging. In contrast, for 5th grade boys reporting expectancies above the mean, prediction of binge eater and purger status was present. It appears that moderate endorsement of the expectancy for overgeneralized life improvement from dieting and thinness is not associated with dysfunction. Only those who endorse that expectancy to an unusually strong degree are at increased risk for eating disordered behavior. It is striking that this pattern held for boys, just as it did for girls.

There were also pathways of potential importance not specified by our theory. In particular, negative urgency was associated with higher levels of linear dieting/thinness expectancies. We did not anticipate that negative urgency, the tendency to act rashly when distressed, would be associated with increased endorsement of the expectancy for overgeneralized life improvement from dieting/thinness. We are reluctant to offer a post hoc explanation for this finding; we believe it needs to be investigated further and replicated. It was also the case that negative urgency had a relationship with binge eating that was not mediated by any of the expectancies: there appears to be a pathway of influence from negative urgency to binge eating beyond what we have specified in our model. Lastly, we were surprised that the expectancy that eating helps one manage negative affect had a relationship with purger status, beyond the relationship mediated by binge eating. Again, we are reluctant to offer a post hoc explanation for this result.

It is important to appreciate the distinction between the model underlying this study and the specific empirical test we conducted. The model we have laid out describes a set of causal processes leading to disordered eating that occur in a temporal sequence. This empirical test did not address the causal nature of the process, nor did it assess the temporal sequence of influences implied by the model. Rather, it tested whether the pattern of associations among these variables in 5th grade boys was consistent with the model. Because the data were consistent with the model, there is merit in investigating it with longitudinal data.

The results of this study should be understood in the context of the study's limitations. The biggest limitation is the study's cross-sectional nature: the model needs to be tested with more rigorous longitudinal methods. However, the temporal sequence of variables proposed in our theory has a strong basis in prior theory and empirical work. It is much more likely that change in pubertal status precedes change in personality than the other way around. Prior longitudinal research, as noted above, has shown that personality predicts subsequent changes in expectancies as related to several types of behaviors, including eating disordered behaviors (Combs et al., in press-b), alcohol consumption (Settles et al., in press), and even business investing (Smith et al., 2006). It thus seems likely that changes in personality precede changes in eating expectancies. Finally, expectancies have been shown to predict the onset of binge eating and purging behaviors in early adolescence (Combs et al., in press-b; Smith et al., 2007), and dieting/thinness expectancy manipulations reduce symptom levels (Annus et al., 2008), so there was good reason to place expectancies prior to binge eating or purging in our model.

Other limitations to this study include the following. We relied on questionnaires to assess each attribute and behavior in 5th grade boys. Though interview assessments may have provided the opportunity for clarification of questions and thus a possible increase in precision, they may also have had a negative effect. It could be the case that boys would be reluctant to admit their eating behavior, and perhaps even their expectancies relating to eating or thinness, in an interview with an adult. Another limitation is that we did not assess the context of the eating disorder behavior. As a result, we know very little about the nature of these early binge eating and purging experiences. Although there is evidence for the validity of each measure we used with children this young, there is a need for continued validation research with this young population.

In summary, it appears that some boys engage in binge eating and purging, even prior to their entry into middle school. This phenomenon should be investigated further. It also appears to be the case that the boys engaging in those behaviors can be differentiated from other boys based on personal characteristics of the boys, including their pubertal status, their personalities, and their psychosocial learning. We hope these findings lead to further investigations of this phenomenon and longitudinal tests of this and related risk models.

Acknowledgments

In part, this research was supported by NIAAA grant RO1AA016166 to Gregory T. Smith.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/adb

Fourteen year old children in the U.S. are most often in middle school; in Australia, they are in secondary school, which goes from year 7 through year 12 of education (typically, this spans the period from age 12 through age 18).

The focus of this investigation was on classic symptoms of disordered eating: binge eating and purging. It is certainly possible that young boys are at risk for different forms of eating or body image dysfunction, such as engaging in extreme behaviors to develop more muscular physiques, and this possibility should be investigated empirically. However, such an investigation was beyond the scope of the current study.

References

- Agras WS, Telch CF. Effects of caloric deprivation and negative affect on binge eating in obese binge eating disordered women. Behavior Therapy. 1998;29:491–503. [Google Scholar]

- Allen MT, Matthews KA. Hemodynamic responses to laboratory stressors in children and adolescents: The influences of age, race, and gender. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:329–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The role of urgency in maladaptive behaviors. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:3018–3029. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annus AM, Smith GT, Masters K. Manipulation of thinness and restricting expectancies: Further evidence for a causal role of thinness and restricting expectancies in the etiology of eating disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:278–287. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner LM, Spillane NS, Anderson KG, Smith GT. Similarities and differences between women and men on eating disorder risk factors and symptom measures. Eating Behaviors. 2004;5:209–222. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K, Lennox R. Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equation perspective. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom D, Mellenbergh GJ, Van-Heerden J. The theoretical status of latent variables. Psychological Review. 2003;110:203–219. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP, Rosso J, Gargiulo J. Validity of self-report measures of girls' pubertal status. Child Development. 1987;58:829–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Carter JC, Stewart DA, Fairburn CG. Eating disorder examination questionnaire: Norms for young adolescent girls. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2001;39:625–632. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A. Why maladaptive behaviors persist: Sources of continuity and change across the life course. In: Funder DC, Parke RD, Tomlinson-Keasey C, Widaman's K, editors. Studying lives through time: Personality and development. 1993. pp. 343–376. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW. Personality development across the life course: The argument for change and continuity. Psychological Inquiry. 2001;12:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman L, Coleman J. The measurement of puberty: a review. Journal of Adolescence. 2002;25:535–550. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs JL, Pearson CM, Smith GT. A risk model for pre-adolescent disordered eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders. doi: 10.1002/eat.20851. in press-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs JL, Smith GT. Personality factors and acquired expectancies: Effects on and prediction for binge eating. In: Chambers N, editor. Binge eating: Psychological factors, symptoms, and treatment. Nova Science Publishers; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Combs JL, Smith GT, Flory K, Simmons JR, Hill KK. The reciprocal acquired preparedness model of eating disorder risk. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0018257. in press-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MJ, Fairburn CG. Demographic and clinical correlates of selective information-processing in patients with bulimia-nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1993;13:109–116. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199301)13:1<109::aid-eat2260130113>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotrufo P, Cella S, Cremato F, Labella AG. Eating disorder attitude and abnormal eating behaviours in a sample of 11–13-year-old school children: The role of pubertal body transformation. Eating and Weight Disorders. 2007;12:154–160. doi: 10.1007/BF03327592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbert KM, Burt SA, McGue M, Iacono WG, Klump KL. Puberty and the genetic diathesis of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:788–796. doi: 10.1037/a0017207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:839–850. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decastro JM, Goldstein SJ. Eating attitudes and behaviors of prepubertal and postpubertal females—clues to the etiology of eating disorders. Physiology of Behavior. 1995;58:15–23. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00027-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski A, Yee DK. Men and body image: Are males satisfied with their weight? Psychosomatic Medicine. 1987;49:626–634. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198711000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;16:363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AE, Camargo CA, Taylor CB, Berkey CS, Frazier AL, Gillman MW, Colditz GA. Overweight, weight concerns, and bulimic behaviors among girls and boys. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychology. 1999;38:754–760. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Smith GT, Cyders MA. Another look at impulsivity: A meta-analytic review comparing specific dispositions to rash action in their relationship to bulimic symptoms. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1413–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Stojek M, Collins B. The effect of negative urgency and sexual assault on bulimic symptoms and direct harm over time. annual meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy; New York. Nov 19–22.2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hagtvet KA, Nasser FM. How well do item parcels represent conceptually defined latent constructs? A two-facet approach. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11:168–193. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as an escape from self- awareness. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:86–108. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohlstein LA, Smith GT, Atlas JG. An application of expectancy theory to eating disorders: Development and validation of measures of eating and dieting expectancies. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Fulkerson JA, Leon GR. Disordered eating precursors in pre- and early adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1997;26:203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Klump KL, Leon GR, Fulkerson JA. Disordered eating in adolescent males from a school-based sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;23:125–132. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199803)23:2<125::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leon GR, Carroll K, Chernyk B, Finn S. Binge eating and associated habit patterns within college-student and identified bulimic populations. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1985;4:43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Leon GR, Fulkerson JA, Perry CL, Early-Zald MB. Prospective analysis of personality and behavioral vulnerabilities and gender influences in the later development of disordered eating. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:140–149. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon GR, Fulkerson JA, Perry CL, Keel PK, Klump KL. Three to four year prospective evaluation of personality and behavioral risk factors for later disordered eating in adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28:181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widamon KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Luce KH, Crowther JH. The reliability of the eating disorder examination- self-report questionnaire version (EDE-Q) International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1999;25:349–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199904)25:3<349::aid-eat15>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna B, Sweeney JA. The emergence of collaborative brain function: fMRI studies of the development of response inhibition. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1021:296–309. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam D, Smith GT, Cyders MA, Fischer S, Whiteside SA. The UPPS-P: A multidimensional measure of risk for impulsive behavior. 2007. Unpublished technical report. [Google Scholar]

- MacBrayer EK, Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Demos S, Simmons J. The role of family of origin food-related experiences in bulimic symptomatology. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;30:149–160. doi: 10.1002/eat.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Wen Z, Hau K. Structural equation models of latent interactions: Evaluation of alternative strategies and indicator construction. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:275–300. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maude D, Wertheim EH, Paxton S, Gibbons K, Szmukler G. Body dissatisfaction, weight-loss behaviors, and bulimic tendencies in Australian adolescents with an estimate of female data representatives. Australian Psychology. 1993;28:128–132. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA. Body image and body change techniques among young adolescent boys. European Eating Disorders Review. 2001;9:335–347. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA. Sociocultural influences on body image and body changes among adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Social Psychology. 2003;143:5–26. doi: 10.1080/00224540309598428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe MP, Vincent MA. The role of biodevelopmental and psychological factors in disordered eating among adolescent males and females. European Eating Disorders Review. 2003;11:315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJV. Temporal stability of the eating disorder examination questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;36:195–203. doi: 10.1002/eat.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. User's guide. 3rd ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles: 2004. Mplus: The comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers. [Google Scholar]

- O'Dea JA, Abraham S. Onset of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in early adolescence: Interplay of pubertal status, gender, weight, and age. Adolescence. 1999;34:671–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adoelscence. 1988;17:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RF, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0017631. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons JR, Smith GT, Hill KK. Validation of eating and dieting expectancy measures in two adolescent samples. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002;31:461–473. doi: 10.1002/eat.10034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Anderson KG. Adolescent risk for alcohol problems as acquired preparedness: A model and suggestions for intervention. In: Monti PM, Colby SM, O'Leary TA, editors. Adolescents, Alcohol, and Substance Abuse: Reaching Teens Through Brief Interventions. Guilford Press; New York: 2001. pp. 109–144. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Simmons JR, Flory K, Annus AM, Hill KK. Thinness and eating expectancies predict subsequent binge eating and purging behavior among adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:188–197. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Williams SF, Cyders M, Kelley S. Reactive personality- environment transactions and the transition to adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:877–887. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience and Behavioral Reviews. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillane NS, Boerner LM, Anderson KG, Smith GT. Comparability of the eating disorder inventory-2 between women and men. Assessment. 2004;11:85–93. doi: 10.1177/1073191103260623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Risk taking in adolescence: What changes, and why? Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 2004;1021:51–58. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:825–848. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Whitenton K. Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls: A longitudinal investigation. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:669–678. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Positive urgency predicts illegal drug use and risky sexual behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:348–354. doi: 10.1037/a0014684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Stairs AM, Settles RF, Combs JL, Smith GT. The measurement of dispositions to rash action in children. Assessment. 2010;17:116–1125. doi: 10.1177/1073191109351372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]