Abstract

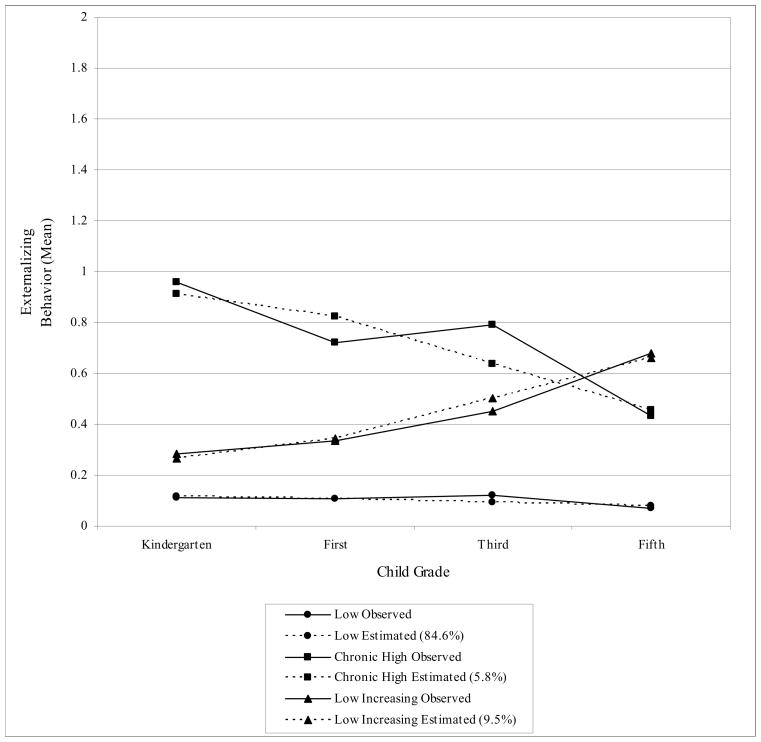

This study utilized growth mixture modeling to examine the impact of parents, child care providers, teachers, and peers on the prediction of distinct developmental patterns of classroom externalizing behavior in elementary school. Among 241 children, three groups were identified. 84.6% of children exhibited consistently low externalizing behavior. The externalizing behavior of the Chronic High group (5.8%) remained elevated throughout elementary school; it increased over time in the Low Increasing group (9.5%). Negative relationships with teachers and peers in the kindergarten classroom increased the odds of having chronically high externalizing behavior. Teacher–child conflict increased the likelihood of a developmental pattern of escalating externalizing behavior. Boys were overrepresented in the behaviorally risky groups, and no sex differences in trajectory types were found.

Keywords: externalizing trajectories, classroom behavior, mixture modeling, teacher-child relationship, peer relationships, parent-child relationship

Childhood externalizing behaviors are associated with a myriad of long-term indicators of maladjustment such as delinquency, substance abuse, and school dropout (Broidy et al., 2003; Moffitt, Caspi, Harrington, & Milne, 2002). In the classroom, these behaviors take up considerable amounts of teacher time and resources and disrupt educational routines for the entire classroom. Although such behavior is usually stable once developed, not all children who express early emerging externalizing behavior manifest behavioral continuity (Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000; Keenan, Shaw, Delliquadri, Giovannelli, & Walsh, 1998) and some older youth with externalizing behavior problems had little to no such behaviors as young children (Moffitt & Caspi, 2001; Moffitt et al., 2002). Understanding which child and relationship factors contribute to sustained externalizing trajectories and which play a role in trajectories that desist or escalate over time will help guide efforts to prevent, and intervene with, such behaviors. In this vein, the aim of the study was to identify whether relationships (a) with parents and child care providers in preschool and (b) with teachers and peers in kindergarten contributed to the prediction of distinct developmental patterns of classroom externalizing behavior from kindergarten through fifth grade.

Relationship Risk and Protective Factors

The complex transactions between children and their environment have been highlighted in the study of child development in general, and the development of externalizing problems in particular (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Dodge & Pettit, 2003; Hill, 2002). According to these developmental and ecologically-oriented approaches, children encounter a variety of circumstances or conditions in their environments that either promote maladaptation or promote competence, with children’s outcomes determined by the balance between these risk and promoting factors. These ecologically-oriented theories place particular emphasis on the importance of relationships between children and the individuals in their immediate environment. In addition, a developmentally sensitive approach recognizes that the salience of specific relationships varies across the lifespan (Boyce et al., 1998). For example, although parents and other family members may be the most salient relationships for young children, the influence of non-familial relationships, such as with teachers and peers, increases as children enter school.

Relationships may have increased impact during certain developmental periods, such as periods of transition (Boyce et al., 1998). Entering elementary school, with its new academic and interpersonal challenges, marks one such transition. During this transition, children may persist on a positive or negative developmental course, or the transition may provide a unique opportunity for their trajectory to be altered (Cowan, Cowan, Ablow, Kahen-Johnson, & Measelle, 2005; Ladd, 1996; Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000). The degree to which adult and peer relationships provide the emotional and behavioral scaffolding needed to adapt to the classroom will likely affect child adjustment during this time (Ladd & Burgess, 2001; Ladd & Kochenderfer, 1996; Pianta, 1999).

Typically, children make the transition to school and embark on trajectories that are characterized by little or no externalizing behavior. However, there are some children for whom the social and academic demands associated with the school transition pose a significant challenge. There are children for whom the known antecedents of externalizing behavior problems are in place prior to school entry. For these children, the social processes of the new classroom may widen the sphere of relationship risk in which maladaptive interpersonal behaviors may be continued or exacerbated, or may provide the opportunity for relationship protection by which these behaviors may be ameliorated. There are also children with little or no prior evidence of risk for whom aspects of the classroom environment may operate as catalysts for externalizing behaviors. For these children, negative relationships with a teacher or peer may set the stage for the development of classroom externalizing behaviors by being a source of conflict or stress. Because children’s social world expands during the transition to school, taking into account the relationships present prior to and after this transition is critical for exploring which relationships have meaningful developmental impact.

Relationships prior to the school transition

Prior to school entry, children’s social worlds primarily revolve around the family. Family relationship dynamics and parenting practices, in particular coercive parent–child interactions, maternal hostility and negativity, and harsh and inconsistent discipline have been shown to promote the early expression of externalizing behavior while maternal responsiveness may serve as a protective factor (Hill, 2002; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992; Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003). With rising child care use, child care has become an increasingly important social environment for children prior to the transition to school (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2002). In fact, increasing numbers of children have had a child care experience before school entry. Many studies have been particularly concerned with the associations between child behavior and the amount of time a child spends in child care, with evidence suggesting that early and extensive child care is associated with increased externalizing behaviors (Belsky, 2001; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network, NICHD ECCRN, 2003). However, issues of quality are also critical for understanding the impact of child care on development. The relationships between children and their child care providers are one marker of quality. Concurrent and longitudinal research has shown that negativity and conflict in the provider–child relationship are indicative of problematic behaviors in the classroom and with peers (Howes, Phillipsen, & Peisner-Feinberg, 2000; Peisner-Feinberg et al., 2001).

Relationships during the school transition

Children do not enter kindergarten as blank slates but instead carry with them behavioral and relational histories. As children’s social worlds increasingly revolve around school, relationships formed in the classroom may serve as important supportive resources or stress-enhancers. Research has illustrated that the quality of the kindergarten teacher–child relationship is associated with school adjustment, aggression, and conduct problems in kindergarten and later grades (Birch & Ladd, 1997; Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Ladd & Burgess, 2001; Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004) and with predictive of growth and decline in classroom externalizing behavior during elementary school (Silver, Measelle, Armstrong, & Essex, 2005).

Peer relationships in childhood are commonly believed to contribute to externalizing development (Dodge & Pettit, 2003; Hill, 2002). In particular, the quality of peer relationships (e.g., peer rejection) seems to be a consistent predictor of subsequent disruptive behavior during middle childhood, adolescence, and adulthood even when accounting for baseline aggression (Coie, Terry, Lenox, & Lochman, 1995; Miller-Johnson, Coie, Maurmary-Gremaud, Bierman, & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2003; Nelson & Dishion, 2004). Importantly, peer rejection has also been shown to contribute to growth in conduct problems and antisocial behavior (e.g., Keiley, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, 2000).

Joint contributions of multiple relationships

As noted previously, ecological theory emphasizes the importance of studying multiple relationships, and the ways in which these multiple relationships work in concert to impact the development of behavior problems (Boyce et al., 1998; Bronfenbrenner, 1977). However, there is a surprising paucity of empirical work examining the simultaneous interplay between multiple relationships and the ways in which interrelated relationships contribute to the development of externalizing behavior. This lack of research leaves gaps in our ability to answer questions such as which relationships are most salient across development, and do later supportive relationships counteract the impact of an early relational insult?

Of extant studies, results regarding independent main effects (i.e., relative impact) have been mixed and contradictory. For example, research with community samples has demonstrated that preschool provider–child relationships (Howes, Matheson, & Hamilton, 1994) and kindergarten teacher–child relationships (Silver et al., 2005), but not parenting, were predictive of social competence and classroom externalizing behavior, whereas research with preschool children deemed to be at developmental risk found the opposite (Pianta, Nimetz, & Bennett, 1997). In addition, one study found child care relationships made a greater contribution to later externalizing behavior than kindergarten teacher–child relationships (Peisner-Feinberg et al., 2001), but a second study found the opposite (Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004). In the NICHD ECCRN studies, various aspects of the family environment have been consistently more predictive of behavioral adjustment than the child care environment (NICHD ECCRN, 2002, 2003).

Evidence for interactive effects (i.e., one relationship effect mitigates or exacerbates the impact of other relationship effects) has also been mixed. In the grades immediately following the transition to school, Hughes and colleagues (1999) found that the correlation between the teacher–student relationship and subsequent aggressive behavior was strongest for children with poor attachment histories (Hughes, Cavell, & Jackson, 1999). However, a second study with this sample found that interactions between harsh maternal parenting practices and the quality of the teacher-student relationship were not predictive of aggressive behavior (Meehan, Hughes, & Cavell, 2003). Similarly, some have found that the aggressive behavior of children described as vulnerable (based on family characteristics and a history of behavior problems) decreased when the child experienced high quality child care (Hagekill & Bohlin, 1995; Peisner-Feinberg et al., 2001), whereas other studies have failed to find significant interactions between child care and family characteristics (e.g., NICHD ECCRN, 1998, 2002).

Person-centered Approaches

The current study took a person-centered approach to understanding which relationships may lead to sustained developmental trajectories and which may play a role in developmental patterns that desist or escalate over time. Person-centered research on externalizing trajectories, which has increasingly used methodologies that empirically derive trajectory groups, such as latent growth curve mixture modeling (Muthén, 2004; Muthén & Muthén, 2000, 2004; Nagin, 2005), has consistently found developmental patterns of chronically high and stable low externalizing behaviors in elementary school; the proportion of children in the chronically high pattern was consistently quite small (i.e., no more than 10% of the sample). In addition, a range of more transient trajectories was derived (Broidy et al., 2003; NICHD ECCRN, 2004; Schaeffer, Petras, Ialongo, Poduska, & Kellam, 2003; Schaeffer et al., 2006; Shaw et al., 2003). There has been no consensus about these other trajectories. However, studies that followed children after the transition to school identified both groups of children who had initially elevated levels of externalizing behavior that desisted by early adolescence (Broidy et al., 2003) and also groups of children who had levels of aggression that increased during elementary school (Schaeffer et al., 2003).

Does extant research suggest that certain relational histories predict distinct developmental patterns of externalizing behavior? Research into this question is limited, but higher levels of family risk (e.g., maternal rejection; NICHD ECCRN, 2004; Shaw et al., 2003) and peer rejection (Schaeffer et al., 2003) have been associated with developmental patterns of chronically high aggression. Research with the teacher–child relationship has not looked at prediction to distinct trajectory groups, but the teacher–child relationship has been shown to exert the most influence on externalizing development for children with a history of aggressive behaviors (Hamre & Pianta, 2001; Ladd & Burgess, 2001; Silver et al., 2005).

The Current Study: Specific Aims and Hypotheses

This study explored the following specific aims and hypotheses. First, this study sought to examine the unique contributions of parents, child care providers, teachers, and peers to distinct developmental patterns of classroom externalizing behavior after the transition to school. Consistent with the literature reviewed above, it was expected that children who experienced negative relationships would be more likely to have trajectories typified by stable or increased levels of maladjustment. In contrast, children who experienced positive relationships would be more likely to have developmental patterns characterized by stable positive adjustment or behavioral improvements. A question of particular interest was which relationships would be relatively more important. Although existing research is scarce and often contradictory, there were two possible hypotheses. One possibility is that preschool relationships would persist beyond the school transition, supporting the notion that these relationships make an early and lasting impact on development. Alternatively, kindergarten relationships would take precedence, supporting the idea that the school transition is disruptive to children and defines a period of development in which relationships have special importance.

Second, this study aimed to identify possible interactions between relationships formed before and after the school transition. Here, too, the extant literature is mixed, but two kinds of interactive effects seemed plausible. On the one hand, kindergarten relationships might be especially important for children who began school at risk due to previous negative relationships such that a positive experience would help counteract emerging externalizing tendencies (e.g., an interaction between negative parenting and positive teacher–child relationships might predict membership in a decelerating trajectory). On the other hand, children who began school at risk might be most detrimentally affected by the negative kindergarten relationships because they provide a new context for expressing preexisting behavior problems (e.g., interactions between negative relationships predict membership in the most risky trajectories).

A final aim was to examine the role of child gender in the prediction of trajectory groups. Historically, the externalizing behavior of females has been studied less frequently than that of males, however, gender is being increasingly discussed (Broidy et al., 2003; Keenan & Shaw, 1997; Moffitt & Caspi, 2001; Moffitt, Caspi, Rutter, & Silva, 2001; Schaeffer et al., 2006). For example, one study identified similar developmental patterns for boys and girls, with males overrepresented in the stable high group (e.g., Broidy et al., 2003). A second found equivalent trajectories for the Chronic High and stable low groups while the moderate trajectories differed between boys and girls (Schaeffer et al., 2006). The manner by which boys and girls arrive at these developmental patterns remains an open empirical question.

Method

Participants

The 241 children (girls = 124) in this study are participants in the Wisconsin Study of Families and Work (WSFW), an ongoing longitudinal study of families and child development (Essex, Klein, Cho, & Kraemer, 2003). At its first assessment wave, the WSFW enrolled 560 families from the Madison and Milwaukee areas during women’s second trimester of pregnancy through obstetrics clinics, private and university hospital clinics, and a large health maintenance organization. Overall, participant attrition in the WSFW has been limited to less than 15% of the original sample.

In this study, we were particularly interested in a selective subsample of children from the WSFW who had a preschool experience. As noted previously, more and more children in the Unites States experience a non-familial caregiver prior to school entry. Because this sample solely included such children, it provided a unique opportunity to examine the joint contributions of familial and non-familial relationships.

Just over 330 children in the WSFW were reported to have some kind of preschool experience. In addition, to be included in this study, children needed to have all information relevant to the predictors of group membership at five time points: preschool (approximately 4.5 years), kindergarten, first grade, third grade, and fifth grade. Subjects also needed information about family socioeconomic status. Due to the analytic methods, children did not need all information about externalizing behavior (see Analytic Plan for additional information). As a result, approximately 90 additional children were excluded from the sample, leaving 241 children.1 The 90 omitted children were missing data on one or more predictor variables for several reasons: (a) lack of teacher report data for home-schooled children, (b) failure by mothers to return a set of questionnaires by mail that contained the preschool behavioral measure, (c) maternal refusal to give information on family income, which was part of the socioeconomic status variable (d) refusal by parents to participate in the home visit that was needed to collect observational measures of maternal responsiveness, and (e) failure by preschool providers to return the questionnaire by mail that contained the provider–child relationship measures.

Analyses comparing the current sample to those children from the WSFW who had a preschool experience but were not included in this study revealed minimal differences between the two groups. There were no significant differences in levels of SES, preschool hostile–aggressive behavior, maternal negativity, child rearing practices, preschool provider–child relationship variables, kindergarten teacher–child relationship variables, and classroom externalizing behavior problems in first, third, or fifth grade. However, children in the current sample came from families with higher levels of maternal positivity, t(289) = −2.16, p < .05, and had higher levels of externalizing behavior problems in kindergarten, t(307) = −2.33= 11.76, p < .05.

The ethnic composition of the current sample (based on mothers’ report of their own ethnicity) was 90.0 % European American (not of Hispanic origin), 3.3 % African American (not of Hispanic origin), 2.5 % Native American, 1.6 % Latino, 1.2 % Asian American, and 1.2 % “other.” According to teachers, 6.8% had had an Individualized Educational Plan (IEP) by or before kindergarten; 8.2% had an IEP during their 5th grade year. When children were in preschool, the mean family income was $71,055 (Mdn = $65,000, range $20,800 to $300,000); most mothers (92.1%) were living with the target child’s biological father; 68.3% of the mothers were working; and the average child was 4.6 years old (range = 4.5 to 5.1).

Measures

Socioeconomic status (SES)

SES has been associated with increased risk for externalizing behavior problems and it was included as an important covariate (Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1994; Miech, Essex, & Goldsmith, 2001). A composite of mother’s and father’s education level and annual family income at child age 12 months and in preschool was used to measure SES. Multiple assessments of family income were included due to the potential volatility of income, especially around the time of and after childbirth, such as in this study (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002). The SES composite was constructed using principal components analysis; over 50% of the variance was explained by the first component.

Child aggressive behavior prior to school entry

A history of early externalizing behaviors is an important risk factor and covariate (Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000; Keenan et al., 1998). When children were in preschool, mothers described their children’s hostile–aggressive behavior in the past 6 months using the Preschool Behavior Questionnaire, which has demonstrated validity, test–retest reliability, and inter-rater reliability evidence among demographically diverse community and clinical samples of 3- to 6-year-old boys and girls (Behar & Stringfield, 1974a, 1974b). Moreover, multiple studies have included this measure in investigations with diverse samples of young children (e.g., Bates, Viken, Alexander, Beyers, & Stockton, 2002; Campbell, 1994; Lyons-Ruth & Melnick, 2004; Silver et al., 2005). The Hostile–aggressive subscale consisted of 11 items such as “Fights with other children, “Blames others,” and “Tells lies” rated on a 3-point scale from 0 (doesn’t apply) to 2 (certainly applies). The score reflected the sum of the items. Test–retest reliability for this scale in the original validity study was .93 (Behar & Stringfield, 1974). In this sample, the internal consistency (coefficient α) was .85.

Observer ratings of maternal responsiveness (negativity and positivity)

When children were in preschool, trained observers made global ratings about mothers’ behavior toward their children after reviewing videotapes of a 2-hour home visit that consisted of 13 tasks designed to assess child temperament (Goldsmith et al., 1993) and three 5-minute mother–child interaction tasks (Clark, 1999). Maternal negativity was measured using the mean of two global ratings: impressions of disapproval/criticism and impressions of intrusiveness. Maternal positivity was measured using the mean of two global ratings: impressions of enjoyment/pleasure and impressions of interest/involvement. Two independent observers made these global ratings on a 5-point scale (1 = no signs, 2 = subtle or ambiguous signs, 3 = mild but ambiguous signs, 4 = moderate, or mild with 1–2 instances of intense display, 5 = consistent signs). In the current sample, the internal consistency (coefficient α) was α = .70 for the Maternal Negativity scale and α = .84 for the Maternal Positivity scale. Raters underwent extensive training and reliability checks; inter-rater reliability (from intraclass correlations) was α = .97 for the Maternal Negativity scale and α = .97 for the Maternal Positivity scale in the current sample.

Maternal child rearing practices and beliefs

Mothers reported on child rearing practices and beliefs using the Block Child-rearing Practices Report (Block, 1965) when the children were in preschool. The Block Child-rearing Practices Report yields high agreement between parents and strong prediction of the psychosocial well-being of 3- to 6-year-old children in unselected, community samples (Block, Block, & Morrison, 1981). The Harsh–Restrictive scale was composed of 11 items. Examples include “I believe physical punishment is the best way of discipline” and “I do not allow (my) child to question my decisions.” The Warm–Supportive scale was composed of 9 items, including, “I have warm, intimate times together with (my) children” and “I respect (my) children’s feelings and encourage them to express them.” Scores reflect the mean of the items. These scales have been used in previous research by the WSFW (Silver et al., 2005). The internal consistencies (coefficient α) were α = .69 for the Harsh–Restrictive scale and α = .76 for the Warm–Supportive scale for this sample.

Peer relationship quality

Kindergarten teachers reported on the quality of children’s relationships with peers using the Child Adaptive Behavior Inventory (CABI; Cowan, Cowan, Heming, & Miller, 1995). The CABI, which yields the Peer Acceptance/Rejection scale, has been evaluated in a community sample of children and has shown associations with children’s academic and social outcomes 2 to 10 years beyond the preschool period (Cowan, Cowan, Ablow, Johnson, & Measelle, 2005; Measelle, Ablow, Cowan, & Cowan, 1998). The Peer Acceptance/Rejection Scale comprised 7 items using a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all like child) to 4 (very much like child). Examples include “Liked by other children” and “Often left out by other children.” This subscale was rationally constructed by the WSFW from several original CABI subscales; there are no previously established or published reliability estimates. In this sample, the internal consistency (coefficient α) was α = .83.

Preschool provider–child relationship quality and kindergarten teacher–child relationship quality

Preschool child care providers and kindergarten teachers rated the quality of their relationship with the target child using a shortened version of the Student–Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS; Pianta, 1996; Pianta, Steinberg, & Rollins, 1995). The STRS was shortened for this study by including the five highest loading items for each scale based on factor loadings reported by Pianta (1996). Five items comprised the Closeness scale (e.g., “I share an affectionate, warm relationship with this child,” “This child openly shares his/her feelings and experiences with me”). The Conflict scale also included five items (e.g., “This child and I always seem to be struggling with each other”). Responses were based on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (definitely does not apply) to 5 (definitely does apply). Published reliability estimates for the full STRS scales (Pianta, Steinberg, & Rollins, 1995) were α = .84 for the Closeness Scale and α =.93 for the Conflict Scale. Reliability estimates for the shortened form of the scales in past work with the WSFW sample were α = .79 for the Closeness scale and .81 for the Conflict scale (Armstrong, Goldstein, & The MacArthur Working Group on Outcome Assessment, 2003). In the current sample, for child care providers, the internal consistency was α = .75 for the Closeness scale and α = .84 for the conflict scale. For kindergarten teachers, the internal consistency was α = .82 for the Closeness scale and α = .88 for the Conflict scale in the current sample.

Child externalizing behavior

A broad measure of externalizing behavior in the kindergarten, first, third, and fifth grade classrooms was reported on by teachers using the Mental Health Subscales of the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ), a parent- and teacher-report measure designed for middle childhood (Ablow et al., 1999; Boyce et al., 2002; Essex et al., 2002). The items in the composite used a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (never or not true) to 2 (often or very true); teachers were asked to report how true each statement was for the target child over the past six months. To represent externalizing behavior, a composite score was constructed by taking the average of three subscale scores: the Oppositional–Defiant Disorder subscale (calculated as the mean of 9 items), the Overt Aggression subscale (calculated as the mean of 4 items), and the Conduct Disorder subscale (calculated as the mean of 11 items). According to the HBQ technical manual, the reliability of the Externalizing composite was .85 in previous work with the WSFW (Armstrong et al., 2003). Internal consistency was α = .93, α = .90, α = .93, and α = .92 for kindergarten and first-, third-, and fifth-grade students, respectively, in the current sample.

Procedure

When their children were in preschool, mothers were interviewed about their child rearing beliefs and practices and about their children’s aggressive behaviors. Trained observers also made global ratings about mothers’ behavior toward their child during a set of semi-structured tasks during a home visit. To obtain information about SES, parents were interviewed during pregnancy, when their children were 12 months, and in preschool about their educational attainment during pregnancy, and mothers were interviewed about family annual income. When the target children were preschool aged, their child care providers or preschool teachers completed a questionnaire about their relationship with these children. In the spring of kindergarten, teachers were interviewed (by phone) about the quality of their relationship with these children and the children’s externalizing behavior. In these phone interviews, interviewers read items aloud and teachers responded with the numeric responses that matched their answers selected from answer cards that had been mailed to the teacher. In the spring of the children’s first, third, and fifth grades, new sets of teachers were questioned about children’s externalizing behavior in the classroom; phone interviews were conducted with first- and third-grade teachers, and fifth-grade teachers completed a questionnaire.

Analytic Plan

Exploration into heterogeneity in externalizing behavior has increasingly used person-centered methodologies that empirically derive trajectory groups, such as latent growth curve mixture modeling (Muthén, 2004; Nagin, 2005). Mixture modeling assumes the distribution of trajectories for the entire sample is not uniform but instead composed of unobserved subpopulations that have a common initial intercept, shape, and rate of change. Here, latent class growth analysis (LCGA), a form of mixture modeling, was used to identify subgroups of children who exhibited distinct externalizing trajectories from kindergarten to fifth grade. In LCGA, means of the growth parameters (i.e., intercept and slope) are estimated for each trajectory group and no variation in the intercept and slope is allowed within classes (Muthén, 2004; Nagin, 2005). There is methodological and conceptual debate about the importance of estimating within-group variability (Muthén, 2004; Nagin, 2005). Here, we were most interested in capturing (and predicting) the variation between, not within, groups which may be best captured by models that do not allow variation within classes (Nagin, 2005).

LCGA was implemented with MPlus (version 4.1, Muthén & Muthén, 2004), using maximum likelihood procedures. This approach accommodates missing data by estimating the model parameters using all available information.2 Individual level trajectories are identified, and individuals are classified based on their likelihood (e. g., posterior probabilities) of class membership. LCGA tests the fit of a growth model for varying numbers of trajectory classes.3 Statistical tests of relative fit, including the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) are most appropriate for determining the best mixture model solution, with lower BIC values indicating a better fitting model (Muthén, 2004). Other considerations include (a) classification quality using posterior probabilities and entropy (a summary measure of membership probability for the most-likely class); (b) the substantive meaning and differentiation of the groups (e.g., whether they have distinct predictors); (c) the bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT), which has been demonstrated to be a very consistent indicator of the number of classes (Jung & Wickrama, 2008; Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthen, 2007); (d) parsimony and interpretability; and (e) validity of groups (Bauer & Curran, 2003; Nagin, 2005).

After identifying latent trajectory classes, analyses were conducted to examine the predictors and correlates of class membership. In accord with several recent papers (e.g., Connell, Dishion, & Deater-Deckard, 2006; Keller, Spieker, & Gilchrist, 2005; Shaw et al., 2003), analyses were completed within a multinomial logistic regression framework in SPSS using group membership information exported from MPlus.4 The impact of child gender on class membership and the predictors of class membership were assessed by (a) incorporating gender as a main effect predictor and (b) examining the potential contribution of interactions between gender and relationship variables.5

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Relationships Among Variables

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for all preschool, kindergarten, first-grade, third-grade, and fifth-grade variables. These data are presented for the sample as a whole and are not reflective of descriptive statistics for the subgroups of children described below. Children in this sample had generally positive relationships with parents, child care providers, kindergarten teachers, and peers. In addition, most children exhibited generally low levels of externalizing behavior at each time point. However, compared to mean levels of teacher-reported externalizing behavior using the HBQ in a clinic-referred sample (Ablow et al., 1999), approximately 9% of the current sample exhibited clinically elevated levels of externalizing behavior in kindergarten. As demonstrated by the sample means, levels of externalizing behavior fluctuated from kindergarten through third grade and then decreased to their lowest level in fifth grade. There were few gender differences, but boys exhibited significantly more externalizing behavior than girls across elementary school. In addition, boys had significantly higher kindergarten teacher–child conflict than girls. Family-wise error was not controlled in these analyses; these effects would not be significant once the large number of comparisons was taken into account.

Table 1.

Observed Means, Standard Deviations, and Gender Differences for the Preschool, Kindergarten, First Grade, Third Grade, and Fifth Grade Variables

| Variable | Totala | Boysb | Girlsc | Gender differences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t | |

| Preschool | ||||||

| Socioeconomic Status | .14 (.99) | .99 (.16) | 2.96 (.31) | .06 (.91) | .22 (1.05) | −1.21 |

| Hostile–Aggressive Child Behavior | 5.81 (3.51) | .41 (.16) | −.11 (.31) | 5.86 (3.74) | 5.76 (3.30) | .23 |

| Harsh–Restrictive Child Rearing | 2.94 (.65) | .05 (.16) | .12 (.31) | 2.98 (.66) | 2.91 (.65) | .90 |

| Warm–Supportive Child Rearing | 6.32 (.45) | −.71 (.16) | .38 (.31) | 6.31 (.44) | 6.33 (.46) | −.24 |

| Maternal Responsiveness, Positive | 4.19 (.75) | −.97 (.16) | .85 (.31) | 4.15 (.72) | 4.22 (.77) | −.71 |

| Maternal Responsiveness, Negative | 1.88 (.73) | 1.17 (.16) | 1.52 (.31) | 1.86 (.68) | 1.91 (.78) | −.51 |

| PCR Closeness | 4.38 (.61) | −1.45 (.16) | 2.46 (.31) | 4.30 (.63) | 4.45 (.57) | −1.90 |

| PCR Conflict | 1.55 (.68) | 1.63 (.16) | 2.75 (.31) | 1.56 (.67) | 1.53 (.70) | .36 |

| Kindergarten | ||||||

| TCR Closeness | 4.37 (.68) | −1.82 (.16) | 4.00 (.31) | 4.31 (.74) | 4.42 (.61) | −1.27 |

| TCR Conflict | 1.45 (.74) | 2.08 (.16) | 3.74 (.31) | 1.57 (.87) | 1.33 (.58) | 2.49* |

| Peer Acceptance/Rejection | 3.59 (.45) | −1.37 (.16) | 1.72 (.31) | 3.60 (.45) | 3.58 (.46) | .32 |

| Classroom Externalizing Behavior | .18 (.27)d | 2.01 (.16) | 4.02 (.31) | .23 (.32) | .14 (.21) | 2.65** |

| First Grade | ||||||

| Classroom Externalizing Behavior | .17 (.23)e | 2.23 (.16) | 6.48 (.32) | .21 (.27) | .13 (.19) | 2.61** |

| Third Grade | ||||||

| Classroom Externalizing Behavior | .19 (.27)f | 1.89(.16) | 3.41 (.32) | .25 (.32) | .13 (.20) | 3.29** |

| Fifth Grade | ||||||

| Classroom Externalizing Behavior | .15 (.25)g | 2.13 (.16) | 4.50 (.34) | .19 (.26) | .11 (.20) | 2.42* |

Note. PCR = Provider–child relationship. TCR = Teacher–child relationship

N = 241.

N = 117.

N = 124.

N = 236 (123 girls).

N = 227 (118 girls).

N = 223 (112 girls).

N = 209 (103 girls).

p < .05.

p < .01.

Intercorrelations among child, family, child care, and classroom risk and protective factors are presented in Table 2. Similar to above, family-wise error was not controlled for this large correlation matrix. In addition, these intercorrelations are for the entire sample and are not representative of patterns for the subgroups of children described below (i.e., these correlations reflect both within-group and between-group variation). These variables were, for the most part, modestly to moderately correlated (Cohen, 1988) with each other (M = .16, range of absolute values = .001–.54). A couple exceptions include the correlations between observed positive maternal responsiveness and observed negative maternal responsiveness (r = −.52, p < .01) and between teacher-reported teacher–child conflict and teacher–reported peer acceptance/rejection in kindergarten (r = −.54, p < .01). These large correlations raise the potential of collinearity in the logistic regression models. Collinearity was monitored, and it did not have a substantive impact on the results.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations among Predictors and Covariates

| Variables | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Socioeconomic Status | −.07 | −.04 | .09 | .16* | −.20** | .08 | −.19** | −.003 | −.10 | .15* |

| 2. Hostile–Aggressive Behavior | - | .29** | −.21** | −.12 | .06 | −.16* | .17** | −.21** | .31** | −.24** |

| 3. Harsh–Restrictive Child Rearing | - | −.29** | −.17* | .17 | −.13* | .13* | −.05 | .11 | −.13* | |

| 4. Warm–Supportive Child Rearing | - | .19** | −.16* | .11 | −.09 | .06 | −.10 | .10 | ||

| 5. Maternal Responsiveness, Positive | - | −.52** | −.002 | .001 | .06 | −.02 | .11 | |||

| 6. Maternal Responsiveness, Negative | - | −.02 | .08 | −.03 | .11 | −.13* | ||||

| 7. PCR Closeness | - | −.35** | .20** | −.10 | .15* | |||||

| 8. PCR Conflict | - | −.04 | .30** | −.25** | ||||||

| 9. Kindergarten TCR Closeness | - | −.32** | .39** | |||||||

| 10. Kindergarten TCR Conflict | - | −.54** | ||||||||

| 11. Peer Acceptance/Rejection | - |

Note. PCR = Provider–child relationship. TCR = Teacher–child relationship

p < .05.

p < .01.

Heterogeneity in Early Externalizing Trajectories

LCGA was used to identify subgroups of children who exhibited distinct developmental trajectories of classroom externalizing behavior across the kindergarten to fifth grade period. To identify the optimal number of trajectory classes, models with varying numbers of classes were estimated with the slope parameter representing a linear shape of change. The model-fitting statistics for this set of models are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Model-fitting Statistics for the Unconditional Growth Mixture Model

| Free parameters | AIC | BIC | SSABIC | Entropy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 class | 9 | −247.81 | −216.45 | −244.97 | .976 |

| 3 class | 12 | −350.79 | −308.97 | −347.01 | .959 |

| 4 class | 15 | −397.44 | −345.17 | −392.72 | .967 |

Note. AIC = Akaike Information Criterion. BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion. SSABIC = Sample Size Adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion. Only growth parameter means varied across groups; no within-group heterogeneity was permitted (i.e., variance for growth parameters set to zero).

According to the model-fitting statistics alone, the four-class model best represented the data; however, the three-class model was deemed most appropriate for the following reasons. In particular, one class in the four-class model had only two members. The proportions of group membership in the three-class model were more substantial, and it had adequate fit and classification quality. Although this three-class model still had two groups small in number, the probability of group membership for these two classes is consistent with past research and theory that demonstrates that the majority of children will have consistently low levels of externalizing behavior with only small subsets of children exhibiting risky developmental patterns of externalizing behavior (see Broidy et al., 2003; NICHD ECCRN, 2004; Schaeffer et al, 2003; 2006; Shaw et al., 2003). Finally, the change in fit between a two- and three-class model (i.e., decreasing BIC statistic), indicated that the three-class model was better fitting than the two-class model. This indication was confirmed by the bootstrap Liklihood Ratio Test (BLRT); BLRT LL value = 132.91, p < .05.6 The observed and model-estimated developmental trajectories from the three-class solution are plotted in Figure 1. Parameter estimates are found in Table 4.

Figure 1.

Trajectory groups identified in the 3-class unconditional model

Table 4.

Parameter Estimates for the 3-Class Unconditional Model

| Estimate | SE | Estimate/SE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (Low) | |||

| Intercept mean | .12 | .01 | 11.37* |

| Slope mean | −.01 | .00 | −2.96* |

| Class 2 (Chronic High) | |||

| Intercept mean | .91 | .12 | 7.66* |

| Slope mean | −.09 | .03 | −3.57* |

| Class 3 (Low increasing) | |||

| Intercept mean | .267 | .09 | 3.07* |

| Slope mean | .08 | .03 | 2.81* |

| Common Parametersa | |||

| Intercept variance | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Slope variance | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Covariance (intercept and slope) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Residual variance, kindergarten | .03 | .01 | 4.45* |

| Residual variance, 1st grade | .03 | .01 | 4.76* |

| Residual variance, 3rd grade | .04 | .01 | 6.08* |

| Residual variance, 5th grade | .02 | .00 | 5.35* |

Parameters were the same across groups because they were constrained to be equal.

p < .05

The majority of the sample (84.6 %, n = 204) was determined to be in the Low group, which was typified by consistently low levels of externalizing behavior across elementary school. In fact, a significant and negative slope mean indicated decreasing externalizing behavior over time. The second class (the Chronic High group) consisted of 5.8 % (n = 14, girls = 2) of the children in this sample. Relative to the other two classes, this group had the highest level of externalizing behavior at baseline (mean difference, Low group = .79, p < .05; mean difference, Low Increasing group = .62, p < .05). In addition, their externalizing behavior exhibited a significant linear decrease over time, as indicated by the significant and negative slope mean. This moderate decrease found among the children who began their externalizing trajectories at the highest level has been demonstrated previously (NICHD ECCRN, 2004; Schaeffer et al., 2003, 2006) and makes sense given the normative decline in aggression associated with improved self-regulatory skills during childhood (Rothbart & Bates, 1998). The third class (the Low Increasing group) consisted of 9.5% (n = 23, girls = 9) of the sample and was characterized by generally low levels of externalizing behavior in kindergarten that significantly increased from kindergarten through fifth grade, as indicated by the significant and positive slope mean. The mean intercept parameter for this class was significantly higher than the Low group (mean difference = .17, p < .05) and significantly lower than the Chronic High group (mean difference = .62, p < .05). The significant and positive values for the mean intercept in all three groups indicated that all classes had baseline levels of externalizing behavior greater than zero; however, in absolute terms, the level of externalizing behavior in kindergarten was fairly low for the Low (intercept = .12, range = 0–2) and Low Increasing (intercept = .27, range = 0–2) groups.

To examine whether the developmental patterns of these trajectory classes were distinct, the observed levels of externalizing behavior were compared to a value indicative of meaningful variation in externalizing behavior. A cut-off of one standard deviation above the observed sample mean was calculated for externalizing behavior in kindergarten and fifth grade (kindergarten M = .18, SD = .27, cut-off = .45; fifth grade M = .15, SD = .24, cut-off = .39). For the Low group, neither the kindergarten (M = .11) nor fifth grade (M = .07) level approached the cut-off. For the Chronic High group, both baseline (M = .98) and fifth-grade externalizing behavior (M = .42) fell above the cut-off. For the Low Increasing group, kindergarten externalizing behavior (M = .31) was below the cut-off while the level was above the cut-off by fifth grade (M = .67).7

Prediction of Group Membership

The major goal of this study was to identify which relationships (e.g., with parents, child care providers, teachers, and peers), and interactions between these relationships, increased or decreased the likelihood of membership in the different trajectory classes. To accomplish this aim, class membership was exported from MPlus into the SPSS platform. A series of multinomial logistic regression models were then constructed using standard guidelines (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 2000). First, univariable multinomial logistic regression models determined which relationship variables were significantly associated with group membership and should be considered for the multivariate model (inclusion criteria = p < .25). Second, a multinomial logistic regression model was run to examine the relative importance of these predictors for group membership. For all models, the Low group (i.e., the largest class) was set as the reference group; thus, the Chronic High group was compared to the Low group and the Low Increasing group was compared to the Low group.8 All models included socioeconomic status, gender, and preschool hostile-aggressive behavior.

Table 5 displays the results from the univariable models. Increased maternal negativity, decreased teacher–child closeness, decreased provide–child closeness, increased provider–child conflict, and decreased peer acceptance were associated with increased odds of being in the Chronic High group. The odds of being in either the Chronic High or Low Increasing groups were higher with increased teacher–child conflict.

Table 5.

Univariable Multinomial Logistic Regression Models

| Parameter Estimates | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic High vs. Low | Low Increasing vs. Low | ||||||

| χ2 Likelihood Ratio Testa | B | SE | Wald | B | SE | Wald | |

| Control Variables | |||||||

| Gender | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SES | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Preschool Hostile–Aggressive Behavior | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Predictors/Covariates | |||||||

| Maternal Responsiveness, Positive | 1.85 | −.33 | .37 | .79 | −.34 | .28 | 1.42 |

| Maternal Responsiveness, Negative | 7.25* | .88 | .38 | 5.54* | −.34 | .34 | 1.00 |

| Harsh–Restrictive Child Rearing | .48 | .30 | .48 | .39 | −.07 | .35 | 1.96 |

| Warm–Supportive Child Rearing | .88 | −.65 | .69 | .89 | −.04 | .52 | .01 |

| PCR Closeness | 4.59 + | −.82 | .39 | 4.67* | .07 | .38 | .03 |

| PCR Conflict | 14.31* | 1.41 | .38 | 13.00* | .44 | .31 | 1.98 |

| TCR Closeness | 7.58* | −.96 | .34 | 7.91* | −.23 | .33 | .50 |

| TCR Conflict | 49.23* | 2.65 | .54 | 24.13* | .85 | .32 | 7.16* |

| Peer Rejection | 31.37* | −3.80 | .83 | 21.13* | −.50 | .54 | .86 |

Note. SES = Socioeconomic status. PCR = Provider–child relationship. TCR = Teacher–child relationship.

This test examines the difference between the model that includes only the control variables (i.e., the reduced model) and the model that includes the control variables and the variable of interest (i.e., the full model).

p < .25.

p < .05.

The results of the multivariable model can be found in Table 6. To ease interpretation, odds ratios that had values less than one (i.e., the coefficient is negative, indicating a decrease in the odds for group membership associated with the variable) were adjusted to be greater than one when discussed in the text by reversing the odds ratio (i.e., dividing one by the value for the odds ratio [1/OR]). This adjustment eases interpretation because odds ratios greater than 1 are more intuitively comprehensible, and all odds ratios are described in the same scale for comparative purposes.

Table 6.

Multivariable Multinomial Logistic Regression Model

| Parameter Estimates | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic High vs. Low | Low Increasing vs. Low | |||||||

| B | SE | Wald | Odds Ratio | B | SE | Wald | Odds Ratio | |

| Control Variables | ||||||||

| Gender | 3.09 | 1.69 | 3.36+ | 21.97 | .53 | .50 | 1.14 | 1.70 |

| SES | 1.21 | .80 | 2.28 | 3.35 | −.44 | .29 | 2.40 | .64 |

| Preschool Hostile– Aggressive Behavior | .02 | .15 | .02 | 1.02 | .12 | .07 | 2.72 | 1.13 |

| Predictors/Covariates | ||||||||

| Maternal Responsiveness, Negative | .13 | .95 | .02 | 1.14 | −.31 | .35 | .78 | .73 |

| PCR Closeness | −.69 | .83 | .69 | .50 | .10 | .40 | .07 | 1.11 |

| PCR Conflict | 1.78 | 1.16 | 2.36 | 5.95 | .45 | .35 | 1.65 | 1.57 |

| TCR Closeness | −.71 | .75 | .90 | .49 | −.08 | .36 | .06 | .92 |

| TCR Conflict | 2.56 | .81 | 10.13* | 12.95 | .77 | .36 | 4.63* | 2.17 |

| Peer Rejection | −2.46 | 1.17 | 4.42* | .09 | .04 | .64 | .004 | 1.04 |

Note. Pseudo R2 = .34 (Cox and Snell); .52 (Nagelkerke); .39 (McFadden). SES = Socioeconomic status. PCR = Provider–child relationship. TCR = Teacher–child relationship.

p < .07.

p < .05.

The potential contributions of interaction terms were also examined in the multivariable model. Interactions with gender, and interactions between relationships formed before and after the transition to school (e.g., parenting by teacher interactions) were examined. Only 1 of these 15 interactions had a likelihood ratio chi square statistic for the interaction that reached statistical significance (i.e., p < .05; Hosmer & Lemeshow, 2000) when comparing a model with the main effects (i.e., the reduced model) to the model with the main effects and the interaction term (i.e., the full model). Because 1 significant interaction out of 15 is not above chance levels and it may not be statistically reliable, interactions were not included in the final model presented.

For the first comparison, increased levels of teacher–child conflict and lower levels of peer acceptance (i.e., higher levels of peer rejection) were associated with increased odds of being in the Chronic High group. With each 1 unit increase in teacher–child conflict and peer rejection, the odds of being in the Chronic High group increased by 12.95 and 11.11, respectively. In addition, being a boy increased the odds of being in the Chronic High group by 21.97; this result was only marginally significant due to the wide confidence interval (CI = .81, 597.72). For the second comparison, increased levels of teacher–child conflict increased the odds of being in the Low Increasing group; the odds increased by 2.17 with each 1 unit increase in teacher–child conflict.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was twofold. First, this study sought to understand the contribution of parents, child care providers, kindergarten teachers, and peers on the development of distinct patterns of externalizing behavior from kindergarten through fifth grade. Second, it examined the role of child gender on the identification and prediction of externalizing trajectories. The results are discussed below.

Heterogeneity in Early Externalizing Trajectories

In this study, LCGA determined that three latent classes best described the heterogeneity in teacher-reported externalizing behavior from kindergarten through fifth grade. A majority of children were in the Low group, which was characterized by consistently low, and significantly decreasing externalizing behavior. There was, however, some variability in developmental patterns. Low initial levels of externalizing behavior that increased significantly until fifth grade typified the Low Increasing group, which composed approximately 10% of the sample. The Chronic High group, which composed less than 6% of the sample, had the highest level of externalizing behavior in kindergarten, which remained elevated throughout elementary school.

That the majority of this sample exhibited consistently low levels of externalizing behavior is consistent with expectations and past research, as is the identification of a small group of children with consistently elevated externalizing behavior (Broidy et al., 2003; NICHD ECCRN, 2004; Schaeffer et al., 2003; 2006; Shaw et al., 2003). The derivation of a Low Increasing group replicated Schaeffer and colleagues’ (2003) developmental pattern that had initially low levels of teacher-reported aggression that increased throughout elementary and middle school. This Low Increasing trajectory has not gained much attention in the theoretical or empirical literature. Although externalizing behavior begins in childhood, the initially low but escalating developmental pattern is distinct from the chronically high trajectories typically derived using mixture modeling and from Moffitt’s (1993) conception of a “life course persistent” group in which externalizing behaviors emerge in early childhood and persists across development. Longer follow-up and additional replication is needed to ascertain whether this developmental pattern is truly distinct from established typologies of externalizing development.

In sum, and as expected in this generally low-risk community sample, most children began elementary school with little to no behavioral risk and continued on this path. However, two subsets emerged with potentially worrisome developmental patterns compared to their peers. There were children whose externalizing behaviors remained elevated throughout elementary school and children for whom increasing levels of externalizing behavior surfaced after the school transition. Although it is unclear whether either group will express problematic levels of externalizing behavior into adolescence, these developmental variations may have detrimental effects among children. It is possible that the risk accrued by these behaviors and their associated corollaries continue to place these children at risk over the course of their life as early disruptive behaviors and negative relationships set the stage for later conduct problems, conflicted relationships, academic difficulties, and other problematic outcomes (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Cicchetti & Toth, 1997; Dodge & Pettit, 2003).

Risk and Protective Factors Associated with Trajectory Group Membership

Of prime interest was which early relationships (e.g., with parents, child care providers, teachers, and peers) predicted distinct developmental patterns of externalizing behavior. Although all four types of relationships made significant predictions to group membership when examined in univariate models, the more temporally proximal, non-familial relationships took precedence in the multivariate model. Higher levels of teacher–child conflict and peer rejection increased the odds of being in the Chronic High group. Boys were also marginally more likely to be in the Chronic High group compared to girls. In addition, more conflict in the teacher–child relationship increased the risk of being in the Low Increasing group. It seems that for children in the Chronic High group, negative relationships with teachers and peers may have contributed to a perpetuation of pre-existing externalizing behavior, reinforcing maladaptive interpersonal behaviors. For the Low Increasing group, conflict in the teacher–child relationship during this transitional year may have served as a trigger that prompted the emergence of these behaviors in the classroom. It is important to note, however, that these findings may not generalize to externalizing behavior in every context and may only be applicable to externalizing behavior exhibited (and reported on) within the classroom setting. These limitations may be especially true because in this study teachers reported on both externalizing behavior and teacher–child relationship quality.

The predictive utility of teachers and peers is consistent with expectations and past research illustrating that children who experienced negative relationships with kindergarten teachers (Hamre & Painta, 2001; Ladd & Burgess, 2001; Silver et al., 2005) and peers (Coie et al., 1995; Schaeffer et al., 2003) were more likely to have early emerging patterns of externalizing behavior. Importantly, this study is the first to demonstrate the effect of kindergarten teacher–child relationships on unique developmental classes of externalizing behavior and is among the first to demonstrate that the teacher–child relationship contributes to the development of externalizing behavior above and beyond other familial and non-familial relationships.

Interestingly, the results of this study indicate that relationships formed during the transition were relatively more important for predicting group membership than the relationships formed before the school transition. The transition to school has been conceptualized as a time when children’s social world expands, with relationships formed during this period having increased developmental salience (Boyce et al., 1998; Cowan et al., 2005; Ladd, 1996). Transitions can be challenging and disruptive for all children (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2000), and negative relationships with teachers and peers may lead to an absence of crucial emotional and behavioral support needed to negotiate the new academic and social demands of the classroom (Ladd, 1996; Pianta, 1999). Having negative classroom relationships with teachers and peers may reinforce or initiate maladaptive interpersonal behaviors, which leads children to persist on externalizing trajectories or switch to a more behaviorally risky trajectory. At this young age, the precedence of the teacher–child relationship over peers makes sense given the critical importance of adult-child relationships during this time. As children age, peer relationships may become more salient and play a larger role in the development of externalizing behavior problems.

Further, these results suggest that non-familial relationships were relatively more important than the parent–child relationship for predicting which children exhibit risky patterns of classroom externalizing behavior. Although previous research examining the joint contributions of familial and non-familial relationships is scarce and mixed, these results are consistent with past findings that the teacher–child relationship (Howes, Matheson, & Hamilton, 1994; Silver et al., 2005), but not parenting, was predictive of behavioral adjustment in the classroom. However, they are at odds with past mixture modeling studies, which did not include classroom relationship variables, that indicated children with chronically high aggression had more family risk (NICHD ECCRD, 2004; Shaw et al., 2003) and with a large body of research illustrating the significance of parenting and the parent–child relationship to the development of externalizing behavior (Dodge & Pettit, 2003; Hill, 2002).

There are many possible explanations for the apparent limited importance of parenting in this study; several will be discussed. First, because the trajectories and classes were derived with teacher data, data (i.e., predictors) from other sources were likely to fare worse in prospective models such as these (Angold & Costello, 1996; Kraemer et al., 2003). For example, the impact of mother-reported parenting practices may have been reduced in this study compared to models in which the trajectories and classes were derived from mother-reported behavior. However, observational measures of the parent–child relationship were also unrelated to group membership, reducing the likelihood that this is solely the product of reporter-driven effects. Second, most children experienced generally good parenting and positive parent–child relationships; the limited variability in this generally low-risk sample may reduce the relative salience of this variable. Although information about parenting was collected from two sources (i.e., trained observers’ ratings and self-report by mothers) to minimize the impact of social desirability, one possible factor leading to reduced variability in these measures is mothers’ altering their self-reports or behavior while observed. Third, parent-child relationships were not measured in kindergarten, making the measures of parent–child relationships less temporally proximal than the measures of non-familial relationships. As a result, concurrent measures of the parent–child relationship were unable to compete with kindergarten teacher and peer relationships in the multivariable model, decreasing the likelihood of significant prediction by the parent–child relationship variables. Finally, as stated previously, it may be that during periods of transition, relationships formed in the ecological context in which the transition occurs have added influence. As a result, parenting effects may be more prevalent with younger children, prior to the entry to school. In fact, a multiple linear regression in which kindergarten externalizing behavior was regressed on the preschool familial and non-familial predictors indicated a trend for increased levels of observed maternal negativity to be associated with increased externalizing behavior in the kindergarten classroom (B = .04, p = .07). As alluded to previously, the interpersonal difficulties between parents and their externalizing child prior to school entry may be reinforced by the interpersonal conflict between teachers and peers and the youth, resulting in precedence of the kindergarten classroom effects.

Finally, this study is one of only a few that has examined the impact of gender on the development of externalizing behavior. There was no evidence to suggest that the trajectory types differed between boys and girls. Past research in this area has been inconsistent (Broidy et al., Schaeffer et al., 2006), and it is possible that the current study did not find such differences due to the low risk nature of the sample and the developmental period assessed. Confirming expectations, boys trended towards being more likely to express worrisome developmental patterns of classroom externalizing behaviors than girls (Broidy et al., 2003); this finding was not statistically meaningful, likely due to power issues. Examination of raw numbers and odds ratios demonstrated that boys were overrepresented in the two behaviorally risky groups, especially the Chronic High group. Girls, however, were not without risk; girls who exit elementary school exhibiting elevated externalizing behavior are more likely to demonstrate the low increasing pattern. Finally, this study did not find evidence for the differential impact of risk factors for boys and girls. Although boys were overrepresented in the at-risk groups, this study allowed no insight into the mechanisms that place boys at increased risk.

Limitations and Areas for Future Research

Although the results from this study are poised to provide understanding into the role of familial and non-familial relationships on the development of externalizing behavior, there were several limitations. First, person-centered methodologies are sample intensive and the use of modestly sized samples, such as in this study, may have important implications for the interpretation of the results. As with all statistical analyses, but especially with mixture modeling approaches, there is a fine balance between model complexity and model stability. Several modeling questions and configurations could not be completely explored (i.e., including covariates of group membership within the mixture model and modeling residual variation), likely due to the modest sample size. Also, power issues may have affected the pattern of significance of predictors in the multivariable model. Replicating the study with a larger sample size would allow for more firm conclusions to be drawn about the nature and number of externalizing trajectory groups and the predictors of group membership.

Second, the relative homogeneity of the sample in terms of ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geographic location limits our ability to generalize. Future research should surely address this limitation. Third, given the low base rates of negative behaviors and troubled relationship processes, replication with a non-community sample is warranted. Such replication is especially relevant given the goal of assessing the relationships that predict membership in behaviorally at-risk trajectory subgroups. Increased variability in the sample (e.g., in terms of problematic behaviors) might increase the likelihood that additional trajectory classes, or groups with more significant numbers of children, would be identified. Fourth, the kindergarten teacher provided the sole report of the teacher–child relationship and peer rejection. Future research should incorporate additional reports of non-familial relationships (e.g., child self-report, sociometric measures, and naturalistic observer ratings). Fifth, we did not control for developmental disability or identified special needs. Given the corresponding behavioral and social-emotional issues associated with developmental disabilities and special needs, it will be important to disentangle these issues in future research. Sixth, given the finding that relationships directly after the school transition were relatively more predictive of group membership, it would be useful to have a measure of parenting concurrent with the school transition. Unfortunately, the WSFW does not have data on the parent–child relationship in kindergarten, which is a limitation to the current study. Similarly, information about children’s relationships with after school child care providers would further untangle the impact of timing effects on the findings presented in this study (Pierce, Hamm, & Vandell, 1999).

Further areas for research should address additional limitations and include the following. First, the inclusion of data continuing to follow these children across the transition to middle school and beyond would provide valuable information about these children’s externalizing trajectories into adolescence. It would shed light on the long-term impact of early emerging externalizing behavior and its associated relational risk. Second, the examination of distal outcomes would also provide another check for the validity of the trajectory classes identified in this study. Third, investigation into whether these results would be replicated with mother-reported trajectories or trajectories derived from a multi-informant scale would help sort out whether reporter bias and contextually-driven effects had a substantive impact on the results. Here, teachers reported on both externalizing behavior and the teacher–child relationship, which is a limitation of the current study. Fourth, since theories of developmental psychopathology propose that human development is truly transactional and bidirectional, the inclusion of time-varying covariates would help provide additional insight into the ways in which relationships and developmental trajectories interact over time.

Clinical Implications

Relationships with adult caregivers and peers are not only experiences that shape adjustment and development, relationship disturbances often occur along with psychological disturbance such that relationship problems are viewed as markers for problematic behaviors. It is difficult to determine definitively whether behavioral disturbance or relationship problems precede the other (Sroufe, Duggal, Weinfield, & Carlson, 2000), and the results of this study are certainly not definitive in this regard. However, understanding the relational experiences that maintain, ameliorate, or exacerbate disruptive behaviors is vitally important, especially in terms of their implications for prevention and intervention efforts (Cowan & Cowan, 2002). The results of this study help provide the evidentiary base for justifying the need to intervene early regarding social competencies and early relationships within the classroom setting; it is not adequate to wait until disruptive behaviors are more entrenched and there is a longer history of failed relationships. School psychologists play an essential role in identifying children with behavioral concerns, supporting and consulting with teachers, and developing and implementing preventive interventions for externalizing behavior in the school setting. Although the findings reported here have clinical implications for the assessment, prevention, and treatment of early externalizing behaviors generally speaking, they may be particularly relevant for the practice of school psychology.

First, the results of this study will aid in the identification of young children at-risk for classroom externalizing behavior problems. Children who have elevated externalizing behavior during kindergarten and children who demonstrate early escalations in their externalizing behavior may be at-risk. In addition, troubled relationships with teachers and peers may be early indicators of risky patterns of externalizing behavior. Identifying these children early, before they transition into middle school, go through puberty, and encounter a new set of biological and contextual challenges is of the utmost importance. School psychologists can assist with early identification efforts through their own behavioral assessments, by educating the larger school community about the developmental course and associated risk of early externalizing behavior, and by promoting universal screening practices.

Second, this study provided justification that preventive interventions should target the social contextual aspects of the classroom. Promoting the use of preventive interventions that aim to alter negative relationship patterns with teachers and peers may be one way to decrease the risk for sustained externalizing trajectories. A growing evidence base has identified effective classroom-based interventions that target increased social competency with peers and positive teacher–child relationships (see Bear, Webster-Stratton, Furlong, & Rhee, 2000; Silver & Eddy, 2006 for reviews). For example, promising programs target the reduction of peer rejection and externalizing behavior by increasing children’s social skill competencies (e.g., Greenberg, Kusche, Cook, & Quamma, 1995; Hudley et al., 1998; Prinz, Blechman, & Dumas, 1994; Shure, 2001a, 2001b; Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1997). In addition, there are strategies that target teachers and teacher–child relationships in an effort to establish positive teacher–child relationships and increase teachers’ use of proactive and non-punitive classroom management (Battistich & Hom, 1997; Hawkins, Von Cleave, & Catalano, 1991; Kellam, Rebok, Pianta, 1999; Reid, Webster-Stratton, & Hammond, 2003; Walker, Kavanaugh, Stiller, Golly, Severson, & Feil, 1998; Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Hammond, 2004).

Third, and consistent with a response-to-intervention framework (Barnett et al., 2006), this study demonstrates that a mixture of universal, selected, and targeted preventive interventions may be warranted within the school setting. Taking a tiered approach will ensure that all children within the school community are exposed to prevention programming and that more intensive interventions are accessible for children who need them. Universal and selected programming is critical for exposing all at-risk children to services since targeted early interventions would likely exclude those at-risk children not identified as having behavior problems in early elementary school based on their developmental patterns. Further, as schools attempt to effectively address classroom externalizing behaviors, school psychologists can consult with teachers to provide an additional, and often necessary, support. Teachers coping with the daily challenges associated with disruptive classroom behavior will greatly benefit from a school psychologists’ expertise regarding practical strategies for handling misbehavior, for promoting prosocial behaviors, and for successfully and sustainably implementing such strategies in the classroom.

Developing positive relationships with children who enter school with difficult behavior may pose a special challenge for teachers, particularly in the face of high numbers of students and heavy academic demands. Although great strides have been made in researching effective programs that have impact on child behavior via teacher–child processes, there is much to be learned, especially regarding the strategies and supports necessary to help teachers develop positive student-teacher relationships with the most challenging students. Teachers who are able to promote positive peer relationships and develop warm and supportive relationships with these students have the potential to alter the course of these children’s externalizing behaviors and reduce the risk for sustained negative developmental outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a Ruth L. Kirschstein Predoctoral National Research Service Award granted to the first author (NIMH grant 1F31 MH68959-01A1), NIMH grants MH44340 and MH52354-Project IV (Marilyn J. Essex, Principal Investigator), and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development (David J. Kupfer, Chair).

Footnotes

Multiple imputation and maximum likelihood are two alternative strategies for handling missing data that lead to less biased estimates when assumptions for data missing at random (MAR) and data missing completely at random (MCAR) are violated (Baraldi & Enders, 2010). Given the evidence that our subsample is representative of the larger WSFW sample, estimates should not be as biased using a deletion strategy as they might be otherwise.

As there is no way to test the MAR assumption, we explored the assumption that repeated measures externalizing behavior data was MCAR. To do this, potential differences on all the predictor variables were examined between (a) children in the final subsample who had missing data on the repeated measures of externalizing behavior and (b) children in the final subsample with complete data on the repeated measures. No significant differences (p < .05) on predictor variables were found between these two groups, providing evidence that this assumption holds true and that the analytic strategies are appropriate.

This model limits the within-class variation (i.e., there is no intercept and slope variance). It is possible that this variability will show up as additional classes and that this LCGA model will indicate more classes than a generalized Gaussian mixture model (GGMM).

When the logistic regression model was run within the MPlus analytic framework, there were several modeling issues that emerged, including problems with convergence. These modeling issues further justified the exportation of class membership information into SPSS for additional analyses.

Unconditional LCGA were also conducted separately by gender. Three class models were deemed best for both boys and girls. In addition, the derived trajectory classes were similar (i.e., Low, Low Increasing, and Chronic High) in that they exhibited the same patterns of change over time. The primary difference was in the Chronic High groups; the girls’ level of externalizing behavior in kindergarten was lower than the boys’, and the girls’ decrease over time was more pronounced. This difference was not deemed substantial enough to split the sample in two in an attempt to conserve power for the remainder of the analyses.

Two other model parameterization issues were explored. First, the possibility that the developmental trajectories of one or more classes exhibited a nonlinear form was examined. The addition of a quadratic term did not improve model fit. Neither the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) nor BIC values indicated improved model fit; in fact, the BIC values got slightly worse. Also, entropy only increased by .04, which may not indicate substantially better classification quality compared to the linear model. Second, the potential presence of autoregressive residual variance (i.e., the impact of externalizing behavior at one time point on the subsequent time point that is not captured by the latent growth parameters) was examined (see Kim, Capaldi, & Stoolmiller, 2003; Stoolmiller, Kim, & Capaldi, 2005). The model fit was only slightly improved with the addition of autoregressive effects; the AIC improved 15 points and the BIC improved less than 5 points. The entropy was lower, indicating worse classification quality than the model without autoregressive errors. There are no set standards for “large enough” changes in relative model fit and entropy; thus, a balance between these indices of model tenability and model complexity must be weighed. Here, it was determined that any improvements, when they did exist, did not provide justification for increasing the complexity of the model with quadratic trends or autoregressive errors.

When these comparisons were conducted using means and standard deviations derived from the model parameters (versus observed scores), the results were substantively equivalent.

Direct comparisons between the Low Increasing and Chronic High trajectory groups would be an ideal supplement to these analyses. Unfortunately, this information was not immediately available due to concerns about the small numbers of children in at-risk trajectory groups (i.e., power); comparisons between the Chronic High and Low Increasing groups were not deemed prudent.