Abstract

Multipotent stromal cells (MSCs) ameliorate several types of lung injury. The differentiation of MSCs into specific cells at the injury site has been considered as the important process in the MSC effect. However, although MSCs reduce destruction in an elastase-induced lung emphysema model, MSC differentiation is relatively rare, suggesting that MSC differentiation into specific cells does not adequately explain the recuperation observed. Humoral factors secreted by MSCs may also play an important role in ameliorating emphysema. To confirm this hypothesis, emphysema was induced in the lungs of C57BL/6 mice by intratracheal elastase injection 14 days before intratracheal MSC or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) administration. Thereafter, lungs were collected at several time points and evaluated. Our results showed that MSCs reduced the destruction in elastase-induced emphysema. Furthermore, double immunofluorescence staining revealed infrequent MSC engraftment and differentiation into epithelial cells. Real-time PCR showed increased levels of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF). Real-time PCR and western blotting showed enhanced production of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) in the lung. In-vitro coculture studies confirmed the in vivo observations. Our findings suggest that paracrine factors derived from MSCs is the main mechanism for the protection of lung tissues from elastase injury.

Introduction

Lung emphysema is a smoking-related disease. Its pathological changes are defined as the permanent enlargement of airspaces distal to the terminal bronchioles, accompanied by destruction of their walls but without obvious fibrosis.1 The course of this disease is irreversible, and there is currently no treatment that is effective in decreasing its destructive effects.2 Consequently, innovative treatments should be investigated. Multipotent stromal cells (MSCs) have the capability of differentiating into various cell types, including endothelial cells, epithelial cells, adipocytes, and osteocytes.3 Systemic administration of MSC is potentially simple and provides a direct therapeutic option for pulmonary diseases.3 Many studies have shown the engraftment capabilities of MSCs in lungs4,5,6 and the ability of these cells to differentiate into type I and type II epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts.7 This engraftment can result from the systemic injection of allogeneic MSCs4 or autologous MSCs.8 Despite the low rates of engraftment,9 the administration of these cells can decrease the intensity of damage caused to the lung by lipopolysaccharides,6 elastase,8 bleomycin,10 naphthalene,11 and asbestos.12 These observations suggest that the mechanisms by which MSCs protect the lung might not only be via their ability to engraft and differentiate but also by other mechanisms. Previously, it has been shown that MSCs can release several types of cytokines, hormones, and growth factors to protect various tissues; these include hepatocyte growth factor (HGF),13 epidermal growth factor (EGF),14 and others.15,16 In general, MSCs secrete soluble factors that are thought to play a significant role in tissue repair rather than transdifferentiation.17 We hypothesized that the intratracheal administration of MSCs into lung tissue affected by elastase-induced emphysema would ameliorate the severity of the disease via their differentiation into various cells required for healing at the sites of injury. MSCs significantly reduced damage in the alveoli and were engrafted at injury sites; however, they disappeared from the lung tissue within a few weeks. Since, we found few differentiated MSCs in the lung tissues, we hypothesized that other factors, such as humoral factors, secreted by the MSCs may play an important role in ameliorating tissue damage caused by emphysema. We therefore evaluated the levels of HGF, EGF, secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in the lung tissues following MSC administration.

Results

Phenotype and differentiation of MSCs

To confirm that the cells used in our experiments were enriched with MSCs, we examined the cell surface markers. Flow cytometric analysis showed that surface marker expression of these cells was: CD105+ (90.3%), CD73+ (88.9%) CD90+ (92.0%), CD45− (7%), and CD11b− (6%) (Supplementary Figure S1a). Furthermore, the MSCs used in the present study retained their differentiation capability. MSCs cultured at passage five readily differentiated into adipocytes when incubated in adipogenic maintenance medium and differentiated into osteoblasts following supplementation of the medium with osteogenic induction medium (Supplementary Figure S1b).

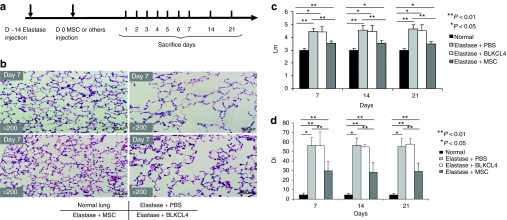

Intratracheal injection of MSCs reduced the development of elastase-induced emphysema

In order to understand the effect of injecting MSCs into lungs with elastase-induced emphysema, elastase was administrated into the trachea of mice. After 14 days, the mice were randomly assigned to receive intratracheal injections of MSCs, BLKCL4 (lung fibroblast cell line; negative control), or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For histological evaluation, mice were sacrificed at days 7, 14, and 21 (Figure 1a). Histological analysis showed that MSCs preserved the alveolar structure of mouse lungs, whereas BLKCL4 and PBS failed to preserve the structure (Figure 1b). Furthermore, the mean linear intercept “Lm” values8,18 and destructive index19 were measured to evaluate the severity of emphysematous changes. MSCs reduced the Lm; however, BLKCL4 failed to reduce the Lm compared with the elastase + PBS group (Figure 1c). Consistently, MSCs reduced the destructive index compared with the elastase + BLKCL4 group (Figure 1d). These results suggest that MSCs are able to ameliorate elastase-induced emphysematous changes.

Figure 1.

Figure 1 MSCs reduced elastase-induced emphysema. (a) The timeline of experiments. Mice were intratracheally injected with elastase 14 days before intratracheal injection with 5 × 105 MSCs, mouse fibroblasts (BLKCL4), or PBS. Mice were sacrificed at days 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 14, and 21 as shown (n = ≥5/group). (b) Representative histological findings (hematoxylin and eosin staining). Treatment with MSCs reduced the elastase-induced emphysema, whereas BLKCL4 (fibroblast cell line) did not reduce these changes. Original magnification ×200. Bars = 50 µm. (c) The mean linear intercepts (Lm) for normal, elastase + PBS-, elastase + BLKCL4-, and elastase + MSC-treated groups. MSCs reduced the emphysematous changes; however, BLKCL4 did not. (d) MSCs restored the lung structure as assayed using the destructive index “DI” compared to normal, elastase + PBS-, and elastase + BLKCL4-treated groups. DI, destructive index; MSC, multipotent stromal cell; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

GFP+ MSCs engrafted in the injury sites but most MSCs did not differentiate into specific lung epithelial cells

To identify the possible mechanism by which MSCs could ameliorate the emphysematous changes, we performed immunohistochemical analysis for green fluorescent protein-positive (GFP+) MSC cells following the same protocol as described above (Figure 1a). GFP+ MSCs were detected after 7 days (Table 1 and Figure 2a). Furthermore, GFP+ MSCs were detectable at days 14 and 21 but with decreased frequency (Table 1). To evaluate whether these MSCs had merely engrafted or had differentiated into epithelial cells, double immunofluorescence staining was performed. We presumed that the MSCs would differentiate into epithelial cells and accordingly screened for the presence of epithelial cell markers, such as alveolar epithelial type 1 marker aquaporin 5,20 on these cells. Previous studies have shown that the contribution of adult bone marrow-derived cells in the restoration of cystic fibrosis-affected lung epithelium is low (0.025–0.01%).21 Our results showed that at day 7 only a small proportion of the injected cells positively expressed aquaporin 5 (Table 1 and Figure 2b). We confirmed the engraftment and differentiation of these cells by confocal microscopy (Figure 2c). We found no GFP+ MSCs that expressed another alveolar epithelial type 1 marker, podoplanin.20 Neither could we detect the alveolar type 2 cell marker, pro-surfactant protein C (data not shown). Many of the GFP+ MSCs did not differentiate into specific lung cells because they did not show double-positive staining and only their native green fluorescence was expressed (Figure 2d). Notably, the numbers of GFP+-stained cells were also lower on days 14 and 21, similar to the results of immunohistochemical staining; we could find no double-positive cells after day 7 (Table 1). These data suggest that the ability of MSCs to engraft and differentiate does not adequately explain the amelioration of emphysematous injuries.

Table 1. A summary of the numbers of detected GFP+ MSCs in lungs.

Figure 2.

MSCs engrafted and differentiated into specific cells in the lung. (a) GFP+ MSCs engrafted in the lung. Arrows indicate GFP+ MSCs (shown at day 7; Original magnification ×200). (b) An MSC cell showed staining for two markers. Immunofluorescence staining at day 7 indicates a differentiated cell. Anti-GFP (green), anti-AQP5 (red), and merged (yellow). Original magnification ×200. (c) x–z confocal imaging of the cell shown in c. Original magnification ×400. (d) Immunofluorescence staining at day 7 shows that most MSCs had not differentiated because they continued to exhibit native green fluorescence only. White arrows show undifferentiated cells, blue dashed arrow show a differentiated cell. The proportions are shown in Table 1. Anti-GFP (green), anti-AQP5 (red), and merged (yellow) Original magnification ×200. The nuclei were stained with DAPI. AQP5, aquaporin 5; GFP, green fluorescent protein; MSC, multipotent stromal cell.

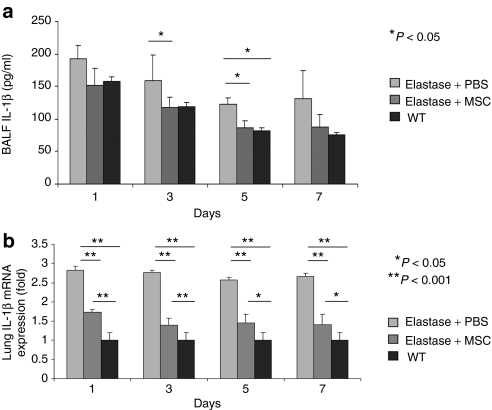

Proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β level was reduced in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and at total lung mRNA levels in response to MSCs induction

In order to identify other possible mechanisms by which MSCs exert their effects, we first assayed the levels of the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β in the lung. IL-1β is responsible for distal airspace enlargement that is consistent with emphysema,22 and it has been shown that the severity of elastase-induced emphysema is decreased in IL-1β knockout mice.23 Recently, it was shown that the development of elastase-induced emphysema depends mainly on inflammasome activation by IL-1β via the IL-1R1/MyD88 signaling pathway.24 Furthermore, it has been reported that MSCs inhibit the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β.25 In our study, the levels of IL-1β in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid decreased gradually after MSCs injection compared with levels in the nontreated groups (Figure 3a). The same pattern was noticed in the wild-type group that received PBS only without elastase. This was confirmed by real-time PCR for total lung mRNA, which showed significant differences in the IL-1β mRNA levels between the treated and both nontreated and wild-type groups (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Inflammatory factor (IL-1β) was decreased in lungs treated by intratracheal administration of MSCs. (a) IL-1β concentration in BALF was measured by ELISA. IL-1β concentration was decreased to the normal levels of the WT groups compared to the elastase + PBS group. (b) Real-time PCR shows a significant decrease in mRNA levels of IL-1β in the MSC-treated groups. Representative data of the first week is shown. Levels of 1L-1β were not changed during the first week. AQP5, aquaporin 5; BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GFP, green fluorescent protein; IL-1β, interleukin-1β WT, wild-type.

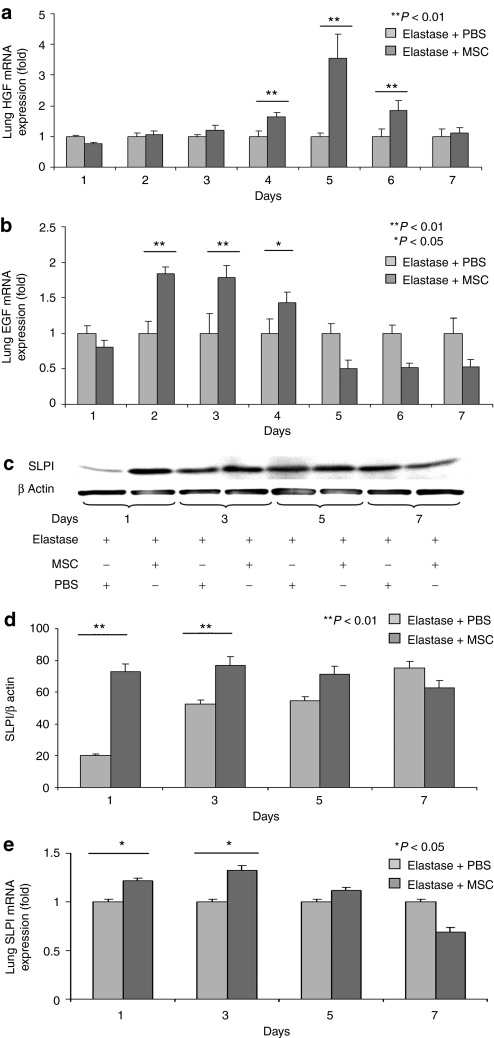

Injection of MSCs resulted in upregulation of growth factors and ameliorated alveolar damage in elastase-induced emphysema

To identify the possible factors produced or induced by the MSCs that affect emphysematous lungs, we assayed HGF levels. HGF is known for its effects in repairing the destruction occurring in emphysematous lungs induced by elastase injection.26,27 Our analysis showed a gradual increase in HGF mRNA levels in MSC-treated lungs beginning from day 3 through day 4 peaked at day 5 and decreased thereafter (Figure 4a). Analyses for other growth factors also showed that EGF mRNA levels were significantly greater than baseline values starting from day 2 through day 3, but were decreased starting from day 4 (Figure 4b). EGF influences the proliferation of many structural cells, including fibroblasts and airway smooth muscle cells, as well as the turnover of matrix proteins.28 EGF is also known for its effect on SLPI;29 therefore, we examined the levels of SLPI protein in the lung. SLPI is responsible for protecting local tissues against inflammation and acts by inhibiting proteases such as elastase.30 Furthermore, it has been suggested that SLPI can protect lungs against the development of emphysema even in α-1-antitrypsin-deficient individuals.31 Our results showed that SLPI expression in treated lungs was significantly increased at both the protein and mRNA levels on days 1 and 3 (Figure 4c–e) in concert with EGF levels, but it was downregulated on days 5 and 7. Although EGF is known to induce SLPI in other systems, we found SLPI peaked at days 1 and 3 whereas EGF peaked at day 3. It is more likely that induction of SLPI is mediated by other factors.

Figure 4.

Growth factors (HGF, EGF) and protection factor for epithelial cells (SLPI; secretory leukocyte protein inhibitor) were increased in lungs treated by intratracheal administration of MSCs. (a) mRNA levels of HGF were increased in the MSC-treated group. (b) mRNA levels of EGF were increased in the MSC-treated group. (c) Western blotting of whole lung extracts shows increased expression of SLPI in the treated mice compared with the nontreated mice. (d) The SLPI bands were further analyzed by densitometry in comparison with the bands of β-actin. (e) mRNA levels of SLPI were significantly increased in the MSCs-treated groups at days 1 and 3 and slightly higher at day 5. Representative data of the first week is shown as levels of SLPI were not changed dramatically during the first 5 days; however, it was downregulated thereafter. EGF, epidermal growth factor; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; MSC, multipotent stromal cell; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

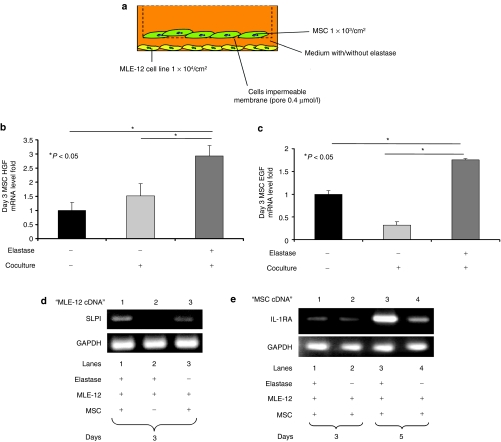

Increased production of IL-1RA, HGF, and EGF by MSCs in coculture with the murine lung epithelial cell line MLE-12

In order to confirm the above results, we conducted experiments using a Transwell coculture system (Figure 5a). The murine lung epithelial MLE-12 cell line was used as an in vitro model, as described previously.32 We confirmed that elastase at a concentration of 0.01 U/ml does not affect the viability of MSCs or MLE-12 cells as determined by measurement of lactate-dehydrogenase activity (LDH Cytotoxicity Assay; Supplementary Figure S2a,b). Furthermore, we confirmed that MSCs do not produce HGF or EGF when cultured with elastase (Supplementary Figure S2c,d). HGF and EGF mRNA levels in MSCs at 72 hours of coculture were significantly increased in the presence of MLE-12 cells with elastase (Figure 5b,c). To confirm that SLPI production was increased in concert with an increase in the levels of EGF, the complementary DNA of MLE-12 cells was amplified after 72 hours of coculture. SLPI mRNA of MLE-12 was notably higher in cells when elastase and MSCs were both present in the coculture system, whereas no increase in SLPI mRNA was observed in the presence of only elastase or MSCs in compare to coculturing well with elastase (Figure 5d). However, in both MSCs and MLE-12 cells, the levels of HGF, EGF, and SLPI were returned near to the baseline level after 120 hours of coculture (data not shown). MSCs have been reported to produce IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA),33 and it was recently reported that IL-1RA diminishes acute elastase-induced emphysema by blocking IL-1.24 We therefore examined IL-1RA levels after 72 and 120 hours (Figure 5e) and found that MSCs produced IL-1RA. We confirmed that such production was not caused by elastase (Supplementary Figure S2e). To confirm that MLE-12 produced IL-1β in vitro, we assayed the IL-1β levels in MLE-12 culture medium. Our data showed that MLE-12 produced IL-1β when elastase exists in the culture medium with or without MSCs at days 3 and 5. However, IL-1β levels where undetectable in the absence of elastase with or without MSCs coculturing at days 3 and 5 (Supplementary Figure S3). This result suggests that MSCs can block the harmful action of IL-1β in our model.

Figure 5.

mRNA levels of HGF, EGF, and IL-1RA from MSCs were upregulated when cocultured with the mouse lung epithelial cell line MLE-12. (a) In the coculture experiments, MSCs were seeded at 1 × 103/cm2 in the upper chamber. MLE-12 cells were seeded at 1 × 104/cm2 in the lower chamber with or without 0.01 U/ml of elastase. Secreted proteins, but not cells, are able to pass through the membrane (pore size, 0.4 µm). (b) The HGF mRNA level of MSCs was increased in the coculture with MLE-12 cells. (c) The EGF mRNA level of MSCs was increased in the coculture with MLE-12 cells. (d) The SLPI mRNA level of MLE-12 cells was increased in the coculture with MSCs. (e) The IL-1RA mRNA level of MSC was increased in the coculture with MLE-12 cells. cDNA, complementary DNA; EGF, epidermal growth factor; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; IL-1RA, IL-1 receptor antagonist; MSC, multipotent stromal cell; SLPI, secretory leukocyte protein inhibitor.

Knocking down EGF in MSCs lowers SLPI production and recombinant EGF induces SLPI production in MLE-12 cells

In order to confirm that EGF from MSCs stimulates SLPI production in MLE-12 cells, we used the small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown technique to decrease EGF levels in MSCs. First, we examined whether siRNA could significantly affect EGF production at 72 hours compared with the production in negative controls (Figure 6a). Next, we used the coculture system described earlier (Figure 5a) with siRNA probes. Real-time analysis showed that SLPI production by MLE-12 cells decreased in the presence of elastase in the coculture system using MSCs with siRNA knockdown of EGF (Figure 6b). To further confirm this relationship, we investigated whether recombinant mouse EGF (rEGF) would enhance SLPI production when added to MLE-12 cells in culture. The results showed that SLPI mRNA levels were significantly increased at various concentrations of rEGF. SLPI mRNA levels were increased at 20 pg/ml of rEGF, peaked at 40 pg/ml, and then progressively decreased at 60, 80, and 100 pg/ml (Figure 6c). However, elastase alone or rEGF presented alone in the medium at a concentration of 50 pg/ml did not enhance the production of SLPI (Figure 6c). These data confirm the novel effect of MSCs in inducing SLPI production through the release of EGF in the MLE-12 epithelial cell line.

Figure 6.

SLPI was decreased when EGF was knocked down in MSCs by siRNA. (a) siRNA knocked down EGF production in MSCs. (b) When MLE-12 cells were cocultured with MSCs transfected with siRNA against EGF or negative control, with or without elastase, the SLPI production of MLE-12 cells was decreased only in the case of MSCs transfected with siRNA against EGF and cultured with elastase. (c) Adding various concentrations of recombinant EGF (rEGF) to the culture medium containing elastase resulted in an increased production of SLPI in MLE-12 cells. Such increase was not noticed when rEGF or elastase alone were exist in the culture medium as assayed by real time PCR. EGF, epidermal growth factor; MSC, multipotent stromal cell; siRNA, small interfering RN; SLPI, secretory leukocyte protein inhibitor.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that MSCs ameliorate elastase-induced emphysematous damage through the release of soluble humoral factors rather than by engraftment in the lung tissue. Briefly, we consider that the effects of MSCs are exerted through the inhibition of IL-1β produced in vivo mainly by macrophage and by epithelial cells in our in vitro model. The upregulation of HGF and EGF in MSCs-treated animals promotes the repair of injuries, whereas the increase in SLPI production protects the lung tissue from the damaging effects of proteases. Our study showed that MSCs can ameliorate elastase-induced emphysema even when they are introduced after 14 days of injury; further, they can decrease the destruction of the alveolar structure in damaged lungs. Our study also showed that this effect of MSCs is mediated through paracrine mechanisms.

Elastase has been widely used as a pathogenic factor to induce emphysematous changes in lungs of several animals. Studies using this model are recent and repeatable.8,24,26,32 Elastase causes massive degradation of the extracellular matrix and tissue cells, releasing a broad variety of degradation products and inflammatory mediators.24 In our study, we detected MSC engraftment even at 3 weeks after administration, but found that only a few MSCs had differentiated into alveolar type 1 cells using aquaporin 5 as a marker. Furthermore, we found no cells positive for podoplanin (type 1) or pro-surfactant protein C (type 2) (data not shown). Although with the aid of confocal microscopy we were able to confirm that certain MSCs had differentiated into alveolar cells, it is unclear whether this alone would be sufficient to cause the observed effects. A number of studies have already reported that MSCs' effect is a paracrine-mediated fashion. This was the case in several types of organs' injuries like myocardial infarction,16 bleomycin,33 neonatal lung injury,34,35 sepsis,36 and endotoxin-induced lung injury.37,38,39 Our study is the first report to show this mechanism to be the main mechanism in ameliorating elastase-induced emphysema. We observed increased levels of HGF, EGF, and SLPI in the treated animals in response to MSC injection, and the release of HGF and EGF from MSC in in vitro experiments. Furthermore, our study presents that SLPI production is induced in epithelial cells in vitro by EGF released from MSCs. The siRNA experiments and the administration of rEGF confirmed this in vitro novel relationship between SLPI and MSC-released EGF. Several reports showed MSCs' effect by assaying the levels of proinflammatory cytokines like “IL-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, interferon-γ” and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as “IL-1RA and IL-10.”33,34,37,40 Other studies focused on certain growth factor like keratinocyte growth factor38 and only limited studies provided hypothesis of how a MSCs' product like prostaglandin E2 will upregulate anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.36 In our study, we are focusing on growth factors like HGF and EGF among other candidates rather than just the downregulation of IL-1β levels. Furthermore, our in vitro experiments showed that such factors might upregulate other factors like SLPI. SLPI protects the lung from the tissue degradation caused by proteases. However, the exact mechanism of this effect in lungs is poorly understood. It has been suggested that SLPI works in partnership with α-1-proteinase inhibitor (the major serum inhibitor of neutrophil elastase) to control the destructive activity of elastase.41 Investigations of the role of SLPI in wound healing and lung cancer suggest that it targets various proteins, such as epithelin, tumor necrosis factor-α, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and IL-6.42 This indicates the multiple effects and complicated mechanism of SLPI in healing and protection against proteases. Considering that only a few cells engrafted and differentiated, this indicates that the production of such cytokines might not have been derived mainly from these cells; as such levels were not sustainable for >5 days after introducing MSCs. This could also explain the transient increase of these factors. In this context, it has been shown previously that there is similar variation in the levels of some anti-inflammatory cytokines after MSC injection at different time points.39 Moreover, the time differential in the decreases of HGF and EGF levels suggest that the MSCs in vivo act as sub-populations that respond differently rather than as a homologous group of cells. One possible mechanism by which the MSCs mediate damaged tissue recovery is the “touch and go” mechanism,43 i.e., through rapid migration to the damaged organ and subsequent clearance following the release of stress-induced therapeutic molecules.43 Our data support this mechanism and further suggest that the time necessary for this mechanism to operate is 3–5 days, which is possibly the life span of MSCs after injection. In general, the results of our study and other studies suggest two interesting points: (i) that there is a combination of factors44 that involved in MSCs effect in each case which means a complex network of factors and cytokines integrated together at multilevels and (ii) although several reports showing the anti-inflammatory effect of MSCs is an IL-1RA- and IL-10-dependent effect, however, the other factors and cytokines are varying depending on the type of injury. In other words, there is no universal set of factors and cytokines to be released/induced by MSCs in all cases. Other studies used MSCs as vector for cell-based gene therapies showed that the efficiency of the treatment was enhanced in comparison to MSCs not transfected with any certain gene.45,46 This further confirms that the paracrine mechanism is the main mechanism of MSCs. Further investigations are needed to elucidate the fate of the administered MSCs; whether they undergo apoptosis and/or acquire the properties of various cells was not considered in the present study. Furthermore, the long-term effects of the engrafted undifferentiated cells in lung tissue need to be clarified. Although our results suggest a clear mechanism for the observed effects of MSCs, it is possible that these effects occur via multiple mechanisms, including engraftment and differentiation.

In conclusion, we consider that MSCs protect lung tissues from injuries via paracrine mechanisms, including increased levels of HGF, EGF, and SLPI and decreased levels of IL-1β. Thus, the administration of MSCs may be a promising therapeutic approach for treating emphysema and other pulmonary diseases.

Materials and Methods

Detailed descriptions of the following procedures can be found in the Supplementary Materials and Methods: mice and cell culture, the induction of adipogenic differentiation, histological analysis, protein and RNA isolation, real-time PCR and reverse transcription-PCR, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid collection and IL-1β measurement using ELISA, immunofluorescence and immunostaining, western blotting, and cytotoxicity assay.

Isolation of mouse MSCs and culture. The isolation of MSCs was performed as we reported previously.47,48 Briefly, the bone marrow of the femurs of 6–8-week-old C57BL/6 or C57BL/6 GFP-transgenic mice (kindly provided by Dr M. Okabe, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan) was flushed out with culture medium. The cells were cultured in low-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (certified for MSC culture; Gibco-BRL) along with 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (Gibco-BRL). After 72 hours, nonadherent cells were removed, and fresh medium was added. At 70–80% confluence, the cells were expanded and used after five passages.

The induction of emphysema in lung tissues and sample collection. Lung emphysema was induced by intratracheal injection of 0.01 (U/g body mass) porcine pancreas elastase (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) as described previously49 using a Microsprayer (Penn-Century, Philadelphia, PA). After 14 days, mice were randomly selected for intratracheal injection of MSCs, GFP+ MSCs, BLKCL4, or PBS. The cells were injected at a concentration of 5 × 105 in 200 µl PBS. The groups used for histological analyses received MSCs, BLKCL4, or PBS, whereas those used for immunohistological and immunohistochemical analyses received MSCs, GFP+ MSCs, or PBS. The mice were sacrificed at days 7, 14, and 21. To check the engraftment of MSCs in mice without lung injury, normal mice received an injection of GFP+ MSCs (5 × 105 cells in 200 µl PBS). These mice were used a negative control group in immunohistological and immunohistochemical analyses. For molecular assays, mice in the MSC and PBS groups were sacrificed at days 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 14, and 21 after MSC injection. Lung protein and RNA were extraction as described in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Coculture experiments. Cells of the MLE-12 lung epithelial cell line (1 × 104/cm2) with or without elastase (0.01 U/ml) were cultured in the lower chambers of a 6-well Transwell system (Corning #2450, New York) with or without MSCs (1 × 103/cm2), which were cultured in the upper chambers for 3 and 5 days. The membrane between the upper and lower chambers (pore size 0.4 µm) is impermeable to cells but permeable to humoral factors. The media were collected and cell RNAs were extracted. The samples were then assayed using real-time PCR and RT-PCR.

siRNA experiments. For silencing experiments, we used siRNA against EGF (Silencer Predesigned siRNA; Ambion, Austin, TX) and negative control (Silencer FAM-labeled negative control#1 siRNA; Ambion). siRNA transfection was carried out using a commercial kit (siPORT Neo FX; Ambion). The knockdown of EGF in MSCs was confirmed after 24, 48, and 72 hours by real-time PCR. Subsequently, MLE-12 and MSCs containing siRNA were cultured in Transwell plates as described above. The SLPI and EGF production of these cells was assayed at 72 hours after the start of coculture using real-time PCR. The following probe was used to knockdown the EGF: sense, CGGGAAGCAUCAUCGAAUAtt; antisense, UAUUCGAUGAUGCUUCCCGct.

Statistical analysis. All values are expressed as the mean ± SD. Differences between the groups were evaluated using a two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test with Sigmaplot version 11 (Hulinks, Tokyo, Japan). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Phenotype and differentiation of MSCs. (A) Flow cytometric analysis for the surface marker expression of the cells used in our experiments. (B) Differentiation of mouse MSCs in vitro. MSCs were cultured in non-differentiating medium (a); MSCs cultured in adipogenic media for 14 days were stained with Oil Red O (b); MSCs cultured in osteogenic media for 3 weeks were stained with Alizarin Red S (c). Figure S2. Elastase showed no effect on viability or inducing cytokine production on MSCs and MLE-12. Measurement of activity of lactate dehyrogenases (LDH Cytotoxicity Assay) showed that elastase at 0.01uni/ml is not affecting the viability of MSCs (A) and MLE-12 (B), when cultured separately. Elastase did not induce production HGF (C) or EGF (D). Elastase also did not induce IL-1RA from MSCs (E). Figure S3. IL-1β levels in MLE-12 culture medium. MLE-12 epithelial cells produced IL-1β when elastase existed in the culture medium with or without MSCs co-culturing at day 3 and day 5. However IL-1β levels were undetectable in absence of elastase with or without MSCs co-culturing. Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (050884) to A.M.K. and grants-in-aid for Scientific research (16390232) to Y.S. (19590878) to H.X., and (21590980) to S.O. from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Supplementary Material

Phenotype and differentiation of MSCs. (A) Flow cytometric analysis for the surface marker expression of the cells used in our experiments. (B) Differentiation of mouse MSCs in vitro. MSCs were cultured in non-differentiating medium (a); MSCs cultured in adipogenic media for 14 days were stained with Oil Red O (b); MSCs cultured in osteogenic media for 3 weeks were stained with Alizarin Red S (c).

Elastase showed no effect on viability or inducing cytokine production on MSCs and MLE-12. Measurement of activity of lactate dehyrogenases (LDH Cytotoxicity Assay) showed that elastase at 0.01uni/ml is not affecting the viability of MSCs (A) and MLE-12 (B), when cultured separately. Elastase did not induce production HGF (C) or EGF (D). Elastase also did not induce IL-1RA from MSCs (E).

IL-1β levels in MLE-12 culture medium. MLE-12 epithelial cells produced IL-1β when elastase existed in the culture medium with or without MSCs co-culturing at day 3 and day 5. However IL-1β levels were undetectable in absence of elastase with or without MSCs co-culturing.

REFERENCES

- Siafakas NM, Vermeire P, Pride NB, Paoletti P, Gibson J, Howard P, et al. Optimal assessment and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The European Respiratory Society Task Force. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:1398–1420. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08081398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, Burkhart D, Kesten S, Menjoge S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1543–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276:71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas M, Xu J, Woods CR, Mora AL, Spears W, Roman J, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in repair of the injured lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:145–152. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0330OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, et al. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Kubo H, Kobayashi S, Ishizawa K, Numasaki M, Ueda S, et al. Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells are important for lung repair after lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. J Immunol. 2004;172:1266–1272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotton DN, Ma BY, Cardoso WV, Sanderson EA, Summer RS, Williams MC, et al. Bone marrow-derived cells as progenitors of lung alveolar epithelium. Development. 2001;128:5181–5188. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizawa K, Kubo H, Yamada M, Kobayashi S, Numasaki M, Ueda S, et al. Bone marrow-derived cells contribute to lung regeneration after elastase-induced pulmonary emphysema. FEBS Lett. 2004;556:249–252. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01399-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loebinger MR, Sage EK., and, Janes SM. Mesenchymal stem cells as vectors for lung disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:711–716. doi: 10.1513/pats.200801-009AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz LA, Gambelli F, McBride C, Gaupp D, Baddoo M, Kaminski N, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell engraftment in lung is enhanced in response to bleomycin exposure and ameliorates its fibrotic effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8407–8411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432929100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AP, Dutly AE, Sacher A, Lee H, Hwang DM, Liu M, et al. Targeted cell replacement with bone marrow cells for airway epithelial regeneration. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L740–L752. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00050.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spees JL, Pociask DA, Sullivan DE, Whitney MJ, Lasky JA, Prockop DJ, et al. Engraftment of bone marrow progenitor cells in a rat model of asbestos-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:385–394. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-1004OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisostomo PR, Wang Y, Markel TA, Wang M, Lahm T., and, Meldrum DR. Human mesenchymal stem cells stimulated by TNF-α, LPS, or hypoxia produce growth factors by an NF kappa B- but not JNK-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C675–C682. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00437.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Tredget EE, Wu PY., and, Wu Y. Paracrine factors of mesenchymal stem cells recruit macrophages and endothelial lineage cells and enhance wound healing. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block GJ, Ohkouchi S, Fung F, Frenkel J, Gregory C, Pochampally R, et al. Multipotent stromal cells are activated to reduce apoptosis in part by upregulation and secretion of stanniocalcin-1. Stem Cells. 2009;27:670–681. doi: 10.1002/stem.20080742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RH, Pulin AA, Seo MJ, Kota DJ, Ylostalo J, Larson BL, et al. Intravenous hMSCs improve myocardial infarction in mice because cells embolized in lung are activated to secrete the anti-inflammatory protein TSG-6. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney DG., and, Prockop DJ. Concise review: mesenchymal stem/multipotent stromal cells: the state of transdifferentiation and modes of tissue repair–current views. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2896–2902. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurlbeck WM. Measurement of pulmonary emphysema. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;65:752–764. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1967.95.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saetta M, Shiner RJ, Angus GE, Kim WD, Wang NS, King M, et al. Destructive index: a measurement of lung parenchymal destruction in smokers. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;131:764–769. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.131.5.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy MC., and, Kasper M. The use of alveolar epithelial type I cell-selective markers to investigate lung injury and repair. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:664–673. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00096003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loi R, Beckett T, Goncz KK, Suratt BT., and, Weiss DJ. Limited restoration of cystic fibrosis lung epithelium in vivo with adult bone marrow-derived cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:171–179. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-309OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen U, Whitsett JA, Wert SE, Tichelaar JW., and, Bry K. Interleukin-1β causes pulmonary inflammation, emphysema, and airway remodeling in the adult murine lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:311–318. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0309OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey EC, Keane J, Kuang PP, Snider GL., and, Goldstein RH. Severity of elastase-induced emphysema is decreased in tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β-receptor-deficient mice. Lab Invest. 2002;82:79–85. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couillin I, Vasseur V, Charron S, Gasse P, Tavernier M, Guillet J, et al. IL-1R1/MyD88 signaling is critical for elastase-induced lung inflammation and emphysema. J Immunol. 2009;183:8195–8202. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tögel F, Hu Z, Weiss K, Isaac J, Lange C., and, Westenfelder C. Administered mesenchymal stem cells protect against ischemic acute renal failure through differentiation-independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F31–F42. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00007.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegab AE, Kubo H, Yamaya M, Asada M, He M, Fujino N, et al. Intranasal HGF administration ameliorates the physiologic and morphologic changes in lung emphysema. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1417–1426. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemura N, Sawa Y, Mizuno S, Ono M, Ohta M, Nakamura T, et al. Amelioration of pulmonary emphysema by in vivo gene transfection with hepatocyte growth factor in rats. Circulation. 2005;111:1407–1414. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158433.89103.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KF. Cytokines in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2001;34:50s–59s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velarde MC, Parisek SI, Eason RR, Simmen FA., and, Simmen RC. The secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor gene is a target of epidermal growth factor receptor action in endometrial epithelial cells. J Endocrinol. 2005;184:141–151. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Mori Y, Hagiwara K, Suzuki T, Sakakibara T, Kikuchi T, et al. Increased susceptibility to LPS-induced endotoxin shock in secretory leukoprotease inhibitor (SLPI)-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2003;197:669–674. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayad MS, Knight KR, Burdon JG., and, Brenton S. Secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor, α-1-antitrypsin deficiency and emphysema: Preliminary study, speculation and an hypothesis. Respirology. 2003;8:175–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plantier L, Marchand-Adam S, Antico VG, Boyer L, De Coster C, Marchal J, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor protects against elastase-induced pulmonary emphysema in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L1230–L1239. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00460.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz LA, Dutreil M, Fattman C, Pandey AC, Torres G, Go K, et al. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mediates the antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effect of mesenchymal stem cells during lung injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam M, Baveja R, Liang OD, Fernandez-Gonzalez A, Lee C, Mitsialis SA, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate lung injury in a murine model of neonatal chronic lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:1122–1130. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200902-0242OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Haffen T, Byrne R, Bonnet S, Rochefort GY, Akabutu J, Bouchentouf M, et al. Airway delivery of mesenchymal stem cells prevents arrested alveolar growth in neonatal lung injury in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:1131–1142.. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200902-0179OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Németh K, Leelahavanichkul A, Yuen PS, Mayer B, Parmelee A, Doi K, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E(2)-dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production. Nat Med. 2009;15:42–49. doi: 10.1038/nm.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N, Su X, Popov B, Lee JW, Serikov V., and, Matthay MA. Intrapulmonary delivery of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells improves survival and attenuates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice. J Immunol. 2007;179:1855–1863. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Fang X, Gupta N, Serikov V., and, Matthay MA. Allogeneic human mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of E. coli endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in the ex vivo perfused human lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16357–16362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907996106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Woods CR, Mora AL, Joodi R, Brigham KL, Iyer S, et al. Prevention of endotoxin-induced systemic response by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L131–L141. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00431.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YS, Oh W, Choi SJ, Sung DK, Kim SY, Choi EY, et al. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuate hyperoxia-induced lung injury in neonatal rats. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:869–886. doi: 10.3727/096368909X471189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingle L., and, Tetley TD. Secretory leukoprotease inhibitor: partnering α1-proteinase inhibitor to combat pulmonary inflammation. Thorax. 1996;51:1273–1274. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.12.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nukiwa T, Suzuki T, Fukuhara T., and, Kikuchi T. Secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor and lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:849–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uccelli A, Moretta L., and, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:726–736. doi: 10.1038/nri2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Du Z, Zhao L, Feng D, Wei G, He Y, et al. IFATS collection: The conditioned media of adipose stromal cells protect against hypoxia-ischemia-induced brain damage in neonatal rats. Stem Cells. 2009;27:478–488. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei SH, McCarter SD, Deng Y, Parker CH, Liles WC., and, Stewart DJ. Prevention of LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice by mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing angiopoietin 1. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Qu J, Cao L, Sai Y, Chen C, He L, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-based angiopoietin-1 gene therapy for acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. J Pathol. 2008;214:472–481. doi: 10.1002/path.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin H, Kanehira M, Mizuguchi H, Hayakawa T, Kikuchi T, Nukiwa T, et al. Targeted delivery of CX3CL1 to multiple lung tumors by mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1618–1626. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehira M, Xin H, Hoshino K, Maemondo M, Mizuguchi H, Hayakawa T, et al. Targeted delivery of NK4 to multiple lung tumors by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007;14:894–903. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaro GD., and, Massaro D. Retinoic acid treatment abrogates elastase-induced pulmonary emphysema in rats. Nat Med. 1997;3:675–677. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phenotype and differentiation of MSCs. (A) Flow cytometric analysis for the surface marker expression of the cells used in our experiments. (B) Differentiation of mouse MSCs in vitro. MSCs were cultured in non-differentiating medium (a); MSCs cultured in adipogenic media for 14 days were stained with Oil Red O (b); MSCs cultured in osteogenic media for 3 weeks were stained with Alizarin Red S (c).

Elastase showed no effect on viability or inducing cytokine production on MSCs and MLE-12. Measurement of activity of lactate dehyrogenases (LDH Cytotoxicity Assay) showed that elastase at 0.01uni/ml is not affecting the viability of MSCs (A) and MLE-12 (B), when cultured separately. Elastase did not induce production HGF (C) or EGF (D). Elastase also did not induce IL-1RA from MSCs (E).

IL-1β levels in MLE-12 culture medium. MLE-12 epithelial cells produced IL-1β when elastase existed in the culture medium with or without MSCs co-culturing at day 3 and day 5. However IL-1β levels were undetectable in absence of elastase with or without MSCs co-culturing.