Abstract

Recombinant adeno-associated viral (rAAV) vector-mediated gene transfer represents a promising approach for many diseases. However, the applicability of rAAV vectors has long been hindered by the small (~4.8 kb) DNA packaging capacity. This limitation can hamper the packaging and delivery of critical regulatory elements and/or larger coding sequences, such as the ~14-kb dystrophin complementary DNA (cDNA) that is of interest for gene therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). Here, we have demonstrated reconstitution of an expression cassette (7.3 kb) encoding a highly functional “minidystrophin” protein (ΔH2–R19, 222 kd) in vivo following intravascular co-delivery of two independent rAAV6 vectors sharing a central homologous recombinogenic region of 372 nucleotides. Similar to previously reported trans-splicing approaches, one rAAV vector provides the promoter with the ~1/2 initial portion of minidystrophin, while the second vector provides the remaining minidystrophin cDNA followed by the polyadenylation signal. Significantly, administering a modest dose [2 × 1012 vector genomes (vg)] of the two minidystrophin-encoding rAAV vectors to dystrophic mice elicited an improvement of physiological performance indicative of prevention or amelioration of the disease state. These studies provide evidence that functional dystrophin transgenes larger than that typically carried by a single rAAV genome can be reconstituted in vivo by homologous recombination (HR) following intravascular co-delivery with rAAV6.

Introduction

Gene transfer vectors based on adeno-associated viruses (AAV), members of the parvoviridae family, are being increasingly utilized to evaluate protein expression longevity in both preclinical and clinical studies. The viral genome of wild-type AAV comprises 4,680 nucleotides flanked by 145 nucleotides inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), and is packaged within the viral capsid in either a plus or minus polarity.1 Consistent with wild-type AAV, the cis-acting ITRs shown to promote the viral life cycle,2,3,4 are incorporated at either side of the substituted transgene cassettes thereby allowing for ~4.5 kb of foreign DNA to be efficiently packaged. The majority of recombinant AAV vectors have been constructed from cloned proviral genomes derived from the AAV2 serotype to achieve transgene expression in mammalian cells.5,6 Within muscle it has been shown that the uptake of rAAV is proceeded by formation of circular genome concatamers resulting in long-term transgene expression.7 Initiation of these circular genomic forms is thought to occur through ITR-mediated intermolecular recombination, where over time a conversion of the monomeric circular form to a high molecular weight circular concatameric form occurs.7,8,9,10 Presently, little information is available regarding the mechanism(s) of transduction persistence and/or large concatamer formation, though cellular DNA repair machinery has been suggested to play a role.11,12,13,14,15

Mutations in the X-linked dystrophin gene that disrupt protein expression result in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), a neuromuscular disorder characterized by body-wide muscle cell degeneration. The monogenic origin and recessive inheritance of this condition make DMD a promising candidate for gene replacement therapy. For genetic diseases such as DMD, the length of the coding sequence for the therapeutic gene (~11.2 kb for dystrophin) often considerably exceeds the size of the wild-type AAV genome. Thus, a major hurdle for rAAV-mediated gene therapy of DMD is the limiting packaging capacity of the viral capsid, with a further challenge being to deliver a highly functional dystrophin transgene to all of the striated muscles of the body. Several groups have utilized highly truncated versions of therapeutic genes by deleting sequences thought to be partially redundant to the main function of the protein.16,17 However, when considering miniaturized dystrophin cassettes, the eight spectrin-like repeat minidystrophin (ΔH2–R19) has been found to provide enhanced physiological function relative to the four spectrin-like repeat microdystrophin (ΔR4–R23/ΔCT).16 Additionally, some evidence suggests that structural abnormalities may be induced by high level expression of microdystrophinΔR4–R23/ΔCT as seen in some muscles of dystrophic mice.18 Therefore, it would be advantageous to consider strategies that allow for the introduction and expression of longer dystrophin-based expression cassettes with the aim of expressing truncated proteins that more closely emulate the capabilities of the full-length isoform. This concept gains further weight when considering that patients whose mutations encode for “minidystrophin-like” proteins (e.g. deletion of exons 17–48) can present with a comparatively mild phenotype,19 whereas it has yet to be established whether patients expressing a “microdystrophin-like” protein would present with a similarly benign condition. Taken together, these observations imply an inherent advantage of delivering minidystrophinΔH2–R19 to DMD patients. In an effort to circumvent the genome size limitation of rAAV, two-part vector systems have been developed, previously referred to as trans-splicing or homologous recombination (HR) approaches.11,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27

In this study, we investigated the hypothesis that simultaneous intravenous delivery of two rAAV vectors containing a short region of homology within the minidystrophinΔH2–R19 gene would allow for reconstitution of a larger gene in vivo within the mdx4cv mouse model of DMD and protect myofibers from degeneration. Most significantly, we demonstrate a reduction in central nucleation, restoration of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex (DGC) to the sarcolemma, and an ability to improve limb muscle physiological performance.

Results

Recombination vector design and strategy for generation of the 6.2-kb minidystrophinΔH2–R19 cDNA in vivo

Previous findings utilizing dual-vector approaches have suggested that the cellular machinery and characteristics of the rAAV lifecycle involving intermolecular concatamerization can facilitate reconstitution of a functional genomic locus larger than can be effectively packaged within a single AAV virion. Relative to the single vector rAAV6/microdystrophinΔR4–R23/ΔCT (rAAV6/µ-dys) we sought to test the functional capacity of minidystrophinΔH2–R19 generation through rAAV genome recombination within the mdx4cv mouse model of muscular dystrophy following intravascular coadministration of two rAAV vectors. Two independent rAAV6/minidystrophinΔH2–R19 (rAAV6/m-dys) recombination vectors were designed with each encoding approximate one-half of the transgene and separate transcriptional regulatory elements (Figure 1a). Although there are a variety of possibilities by which rAAV genomes can assimilate given the polarity and directionality, we hypothesized that an identifiable portion of concatamers would be in the proper head-to-tail orientation (Figure 1b) and provide for a functional benefit to the transduced myofiber.

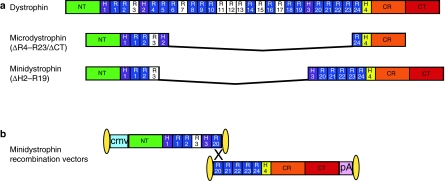

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of rAAV6 recombination vectors for generation of the 222 kd minidystrophin protein. (a) Structural domains of the full-length dystrophin, microdystrophin (ΔR4–R23/ΔCT), and minidystrophin (ΔH2–R19) proteins. (b) The rAAV6 recombination vectors are flanked by the inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) of serotype 2 at both ends (oblong circles). The locations of the CMV promoter (blue) and SV40 polyadenylation (pA) signal (pink) sequences are shown. The two vectors encode either the 5′ or the 3′ approximate half portions of the minidystrophin transgene. The 5′ cassette ends within exon 53 (approximate middle of R21) at nucleotide 7,980 of the human dystrophin cDNA sequence. The 3′ cassette begins within exon 51 (approximate middle of H3) at nucleotide 7,608 and terminates within exon 79 at nucleotide 11,564 of the human dystrophin complementary DNA sequence. Following coadministration in vivo, the two vectors assemble through a homologous recombination mechanism (×), allowing formation of an mRNA that encodes a larger and nearly fully functional minidystrophin where the correctly recombined genome is ~7.3 kb. Note that basic repeats are shaded white. CMV, cytomegalovirus; CR, cysteine-rich domain; CT, carboxy-terminal domain; H1–4, hinges 1–4; NT, amino-terminus; R1–24; spectrin-like repeats 1–24.

Molecular evidence for minidystrophinΔH2–R19 recombination

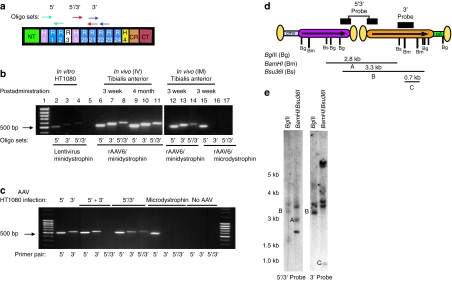

To detect minidystrophinΔH2–R19 recombination events, total DNA was isolated from tibialis anterior (TA) muscles. PCR analysis was performed using three primer pairs that annealed to the upstream and downstream rAAV vectors or the recombination region, enabling detection of starting genomes and recombined minidystrophinΔH2–R19 genomes (Figure 2a). PCR products obtained from intravenously transduced [2 × 1012 vector genomes (vg)/mouse] muscles are shown at 3 weeks (lanes 6–8) and 4 months (lanes 9–11) postadministration (Figure 2b). The recombined minidystrophinΔH2–R19 genome was easily detected at both time points. Similarly, PCR products obtained from TA muscles 3 weeks following intramuscular administration of 1 × 1010 vg of either the dual rAAV6/minidystrophin vectors (lanes 12–14) or the single rAAV6/µ-dys vector (lanes 15–17) to mdx4cv mice are also shown in Figure 2b. Muscles injected with the dual recombination vectors clearly showed the presence of the recombined genome (lane 14), whereas muscle injected only with the microdystrophin vector failed to yield a PCR product with either the 3′-primer pair or the recombination region primer pair (lanes 16–17). Similarly, DNA from muscles injected with only one of the dual minidystrophin vectors were only PCR positive for the primer pair complementary to the input vector (data not shown). In a control experiment (Figure 2c), we infected HT1080 cells with either single and/or dual rAAV/minidystrophin virions followed by DNA extraction and PCR amplification. Importantly, we did not detect bridged PCR products when using DNA template derived from cells infected with either the upstream or downstream vectors when added into the PCR reaction (Figure 2c, lane 6).

Figure 2.

Molecular analysis of rAAV6/minidystrophin genomes. (a) Oligonucleotide primer pairs used for the detection of individual rAAV6/minidystrophin vector genomes (vg). The 5′oligo pair (green arrows) was designed to amplify the 5′ rAAV genome in the region encoding spectrin-like repeats 1–3 (R1–R3; see below); the 3′ oligo pair (blue arrows) amplifies the 3′ rAAV genome in the region encoding R21–R22; the 5′/3′oligo pair (red arrows) yields a product representative of the recombination junction, amplifying DNA encoding the region from H3–R21. (b) PCR analysis of vg using DNA extracted from the tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of mice administered the dual recombination vectors intravenously (i.v.; 2 × 1012 vg, lanes 6–11) or intramuscularly (i.m.; 1 × 1010 vg, lanes 12–14). As a negative control, some mice were also injected with the single rAAV6/microdystrophin vector (i.m.; 1 × 1010 vg, lanes 15–17). As a positive control, HT1080 cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 10 with a lentiviral vector expressing minidystrophin (lanes 2–4). (c) PCR analysis of vg obtained via DNA extracted from HT1080 cells infected with individual or dual rAAV-minidystrophin overlapping vectors. When mixing DNA obtained from cells infected independently with either AAV-5′ or AAV-3′ vectors (lanes marked 5′ + 3′) the 5′/3′ primer pair (lane 6) resulted in no amplification (i.e. no bridged, or recombinant PCR products were detected). Amplification of the 5′/3′ region was only detected when the two vectors were coinfected into the cells (lanes marked 5′/3′). (d) Diagram of rAAV6/minidystrophin recombination vg with restriction enzyme cut sites and representative probes used for Southern blot analysis as described for e. Dual-vector head-to-tail orientations are represented by arrows pointing in the same direction. Inverted terminal repeats are shown as oblong circles. The vector–vector junction may contain 0, 1, or 2 ITRs, and as a result the predicted sizes of hybridized genomes (Supplementary Table S1) are accurate to within ~160 base pairs. The probes utilized hybridize to sites indicated by the black bars shown above the vector genome diagram. (e) Southern blot analysis of total DNA from mdx4cv TA muscles harvested 5 months after i.v. injection of the dual rAAV6/minidystrophin recombination vectors. DNA was digested with BglII or in a separate reaction with BamHI plus Bsu36I followed by hybridization with each of the two probes as indicated. The positions of size standards (in kilobases) are shown on the left. In myofibers transduced with both of the minidystrophin vectors, the BamHI/Bsu36I-digested DNA, when hybridized with the 5′/3′ probe, displayed a band of 2.3 kb in size representing reconstituted minidystrophinΔR4–R23/ΔCT genomes (a). Similarly the BglII-digested DNA when hybridized with either the 5′/3′ or the 3′ probe revealed a 3.3-kb band, diagnostic for the 5′/3′—minidystrophin genomes arranged head–tail (b). The 3′ probe also revealed a 0.7-kb band representing total 3′-minidystrophin monomeric genomes as a result of detecting the BamHI-digested DNA (c). CMV, cytomegalovirus; rAAV, recombinant adeno-associated virus.

To identify the types of recombination that had occurred (head to tail, tail to tail, etc.) and more importantly to confirm proper assembly of the 6.2-kb minidystrophin genome, we performed Southern blot analysis on DNA extracted from transduced mdx4cv muscles. Figure 2d shows a schematic of the probes used and the location of restriction sites present in the starting vectors. Figure 2e shows blots obtained with the two probes following digestion of muscle DNA with either BglII or with BamHI plus Bsu36I, the details of which are denoted in Supplementary Table S1. Importantly, we confirmed the presence of fully constituted minidystrophin genomes by detection of a diagnostic 2.3-kb Bsu36I fragment with the 5′/3′ probe (Figure 2e, band A). Similarly, a 3.3-kb BglII fragment was detected with either the 5′/3′ or 3′ probes, again representing reconstituted minidystrophin genomes (Figure 2e, band B). Other restriction fragments were not diagnostic as they were not able to distinguish different forms of the vg. For example, a 0.7-kb BamHI fragment that was not diagnostic of vector genome orientation was detected when using the 3′ probe (Figure 2e, band C). Despite the clear presence of properly oriented 5′–3′ vectors arranged head to tail several of the detected restriction fragments indicated that other concatamerized vector forms were also formed. For example, hybridization with the 3′ probe showed evidence that some of the 3′ vg were arranged in a head-to-tail formation, as indicated by the 3.6-kb BglII fragment (Figure 2e and Supplementary Table S1). As well, additional fragments could not be attributed to a single population of recombination events such as fragments seen at 2.7 or 3.6 kb (Figure 2e and Supplementary Table S1).

Intravenous administration of rAAV6/minidystrophinΔH2–R19 recombination vectors into 1-month-old mdx mice yields broad dystrophin expression within striated muscles

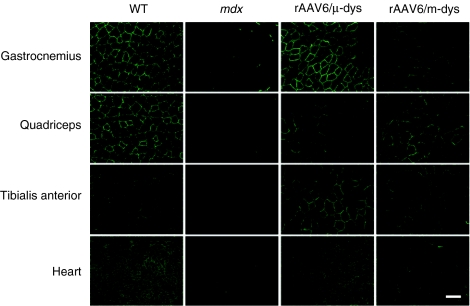

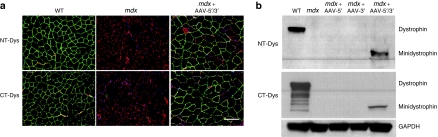

In order to evaluate the transduction potential of the minidystrophinΔH2–R19 recombination vectors using a systemic delivery approach, we administered a suboptimal dose of 2 × 1012 vg intravascularly to 3-week-old mdx4cv mice. Similarly, within a second cohort of mdx4cv mice, we administered an equivalent dose of rAAV6/microdystrophin. Twenty weeks after the administration of vectors, we evaluated dystrophin expression within striated muscle by immunofluorescent staining of cryosections using a dystrophin antibody that recognized the amino-terminus of the protein (Figure 3). As we have previously reported with rAAV6/microdystrophin, the vast majority of the muscle fibers were found to be transgene-product positive (gastrocnemius, TA, quadriceps, and heart).28 Similarly, we found considerable expression within these same muscles when using the rAAV6/minidystrophin recombination vectors. However, larger differences in expression were noted within the heart with minidystrophin as compared to microdystrophin. In addition, limited expression was found within the diaphragm after administering the rAAV6/minidystrophin recombination vectors, perhaps due to the somewhat low dose (data not shown). In turn, we evaluated protein expression using both N- and C-terminal antibodies to ensure detection of the full-length protein (Figure 4a,b). As demonstrated by either immunofluorescent staining or immunoblotting, we show the generation of full-length minidystrophin following the administration of AAV-minidystrophin recombination vectors in vivo. To determine whether the minidystrophin vectors led to restoration of dystrophin-interacting proteins, we evaluated several components of the DGC. Immunofluorescent staining of TA muscle showed a direct correlation between dystrophin-positive myofibers and DGC components when either the mini- or microdystrophin vectors were used (Figure 5a). In view of the considerable forces imposed on the myotendinous junction and the contribution of dystrophin at this location, we also evaluated dystrophin expression within longitudinally sectioned gastrocnemius muscles by immunostaining and confocal microscopy using wild-type, mdx4cv, and mdx4cv mice treated with microdystrophin or the minidystrophin recombination vectors (Figure 5b). There was a qualitatively high level of enrichment of minidystrophin at the myotendinous junctions, suggesting a considerable contribution toward the reduction in shear stress across myofibers.29

Figure 3.

Mini- and microdystrophin generated in vivo following delivery of rAAV6 vectors both properly localized to the sarcolemma of striated muscles in treated mdx mice. Administration consisted of injecting 2 × 1012 vector genomes i.v. in a 0.3 ml total volume. Analysis was at 4 months postinjection. Green fluorescence represents dystrophin staining as detected by a polyclonal antibody to the amino-terminal domain.46 Bar = 100 µm. rAAV, recombinant adeno-associated virus; WT, wild type.

Figure 4.

Minidystrophin protein expression detection as revealed by immunofluorescence and immunoblotting using either an N- (NT) or C-terminal (CT) dystrophin antibody. (a) Cryosections of tibialis anterior muscle treated with rAAV-minidystrophin overlapping vectors demonstrate proper localization at the sarcolemma when detected by NT or CT antidystrophin antibody. (b) Similarly immunoblotting of whole muscle lysates from tibialis anterior muscle demonstrate detection of the 222 kd protein with either the NT or CT antidystrophin antibody. rAAV, recombinant adeno-associated virus; WT, wild type.

Figure 5.

Intravenous delivery of rAAV6/ microdystrophin or dual rAAV6/minidystrophin recombination vectors results in the proper localization of cytoplasmic peripheral and integral membrane protein components of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex and concentration at the myotendinous junctions of treated mdx mice. (a) TA muscles from treated and untreated mice were cryosectioned followed by immunofluorescence staining for α-dystrobrevin-2 (αDb2) and δ-sarcoglycan (δSg), shown as green labeling, with nuclei seen as blue. Bar = 100 µm. (b) An amino-terminal dystrophin antibody was used for immunofluorescent staining of longitudinally cryosectioned gastrocnemius muscles from wild-type, mdx4cv, and mdx4cv treated with either rAAV6/ microdystrophin or rAAV6/ minidystrophin recombination vectors. Bar = 40 µm. rAAV, recombinant adeno-associated virus; WT, wild type.

rAAV6 delivery of minidystrophinΔH2–R19 improves muscle histopathology in mdx mice

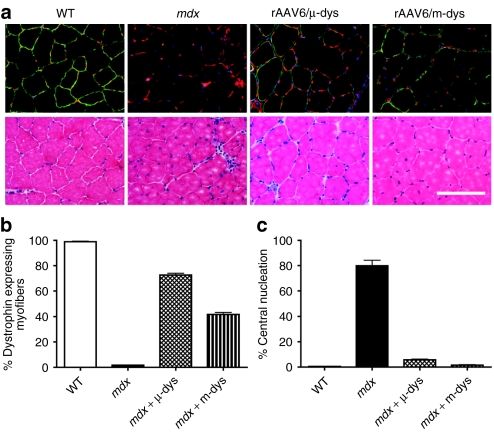

The TA muscle was studied to evaluate therapeutic efficacy within the mdx4cv mouse model. In mice that received intravenous administration of either rAAV6/microdystrophin or the dual rAAV6/minidystrophin vectors, there was a considerable reduction of inflammatory infiltrates as revealed by hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 6a). A transduction efficiency of 72.6% (±2.8) was observed in mice that received AAV6/microdystrophin compared to 41.7% (±3.1) in mice that received the rAAV6/minidystrophin recombination vectors (Figure 6b). Consistent with these results, we observed a reduction in the percentage of centrally nucleated myofibers, an indicator of degeneration and regeneration. In dystrophin-positive myofibers, we observed 5.8% (±1.2) centrally nucleated fibers in microdystrophin-expressing muscles, compared with 1.6% (±0.7) in muscles expressing minidystrophin (Figure 6c). Similar to mdx4cv control mice, ~80% of the myofibers not expressing dystrophin displayed central nucleation in both treatment groups. The ability of both microdystrophinΔR4–R23/ΔCT or minidystrophinΔH2–R19 to prevent features of muscle degeneration as presented here agrees well with previous transgenic mouse data generated in our laboratory.16

Figure 6.

rAAV6-mediated transduction with minidystrophin improves muscle histopathology in mdx mice. (a) Upper panel shows immunofluorescent staining of tibialis anterior muscle for B2 laminin (red), dystrophin (green), and nuclei (blue). The lower panel shows adjacent sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (b) Shows the percentage of dystrophin-positive fibers in the different experimental groups while c shows the percentage of myofibers with centrally located nuclei in the TA muscles. Bar = 100 µm. Bars represent SEM. rAAV, recombinant adeno-associated virus; WT, wild type.

Intravenous administration of rAAV6/minidystrophinΔH2–R19 to mdx mice results in increased muscle function

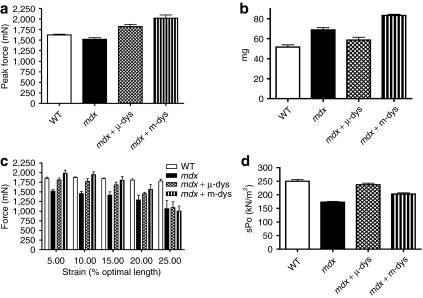

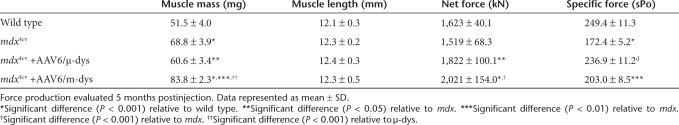

We measured the physiological properties of TA muscles 20 weeks after the administration of 2 × 1012 vg of rAAV6/microdystrophin or the dual rAAV6/minidystrophin vectors. Specific force, representing net force production normalized to the cross-sectional area of the muscle, was reduced by 31% in mdx4cv TA muscles when compared with wild-type muscles (N = 4; P < 0.001; Figure 7a, Table 1). The specific force was improved in TA muscles by ~40 and ~18% relative to untreated muscles for the microdystrophin and minidystrophin cohorts, respectively (N = 4; P < 0.001, P < 0.01). Although the specific force generation was greater in muscles expressing microdystrophin compared to minidystrophin, we note that minidystrophin-expressing muscles generated greater peak force and were larger than microdystrophin-expressing muscles (Figure 7a,b). Thus, the reduction in specific force may be a consequence of the larger overall size of the minidystrophin-expressing muscles. We further tested the ability of either treatment (mini- versus microdystrophin vectors) to protect skeletal muscles from eccentric contraction-induced injury (Figure 7b). In this case, we implemented an in situ protocol that strains the TA muscle in a series of 5% incremental increases above the optimal length during muscle contraction.30 We observed an improvement in protection from contraction-induced injury when comparing untreated mdx4cv muscles to muscles from either treated cohort of mdx mice. When comparing to wild-type muscles at 20% stretch beyond optimal length, contractile force of the treated muscle was reduced by 20 and 13% in the microdystrophin and minidystrophin-expressing muscles, respectively, while untreated muscles displayed a 29% reduction.

Figure 7.

Intravenous administration of rAAV6/minidystrophin recombination vectors to mdx mice results in increased muscle function. In comparison to mdx4cv tibialis anterior (TA) muscles expressing minidystrophin, the TA muscles of untreated mdx4cv mice exhibited (a) reduced force generating capacity; (b) decreased mass; (c) an increased susceptibility to eccentric contraction-induced injury, and (d) decreased force generation per cross-sectional area (specific force). Bars represent the SEM. sPo, specific force; WT, wild type.

Table 1. Contractile properties of tibialis anterior muscle.

Discussion

Numerous investigators have shown the exceptional promise of rAAV vectors for muscle-directed gene therapy. In a recent study, considering key rAAV serotypes with potential to transduce musculature, rAAV6 was found to be superior for cardiac transduction in the canine animal model, being further suggested as the serotype of choice for future clinical trials.31 To address the size constraints of rAAV, several serotypes such as rAAV5 have been studied in an effort to package larger genomes.32 However, the actual packaging capacity of rAAV/5 is somewhat controversial in light of recent evidence regarding the inability to package or express several oversized reporter genes, or an 8.7-kb minidystrophin transgene.33,34,35 It was proposed that reconstitution of an oversized transgene may be generated through the packaging of truncated gene products followed by recombination in vivo. Indeed, each AAV serotype likely binds with distinct cell surface receptors effecting different levels of transduction in different tissue types. Transduction is also influenced by specific host intracellular factors in ways that affect capsid uncoating,36 trafficking, and ultimately conversion of vg to transcriptionally active forms.37 Therefore, future studies may benefit most from choosing a vector serotype that displays maximal tissue-specific targeting while employing alternate mechanisms to increase the ability to deliver larger transgenes (such as recombination approaches). Recently, it has been shown that adverse architectural alterations can be found in some mdx4cv mouse muscles expressing the commonly used microdystrophinΔR4–R23/ΔCT, which may limit the usefulness of this transgene compared with larger isoforms.18 Indeed, this limitation was not observed in muscles expressing a larger minidystrophinΔH2–R19, nor has it been found with some modified microdystrophins.18,38

Although recombinant AAV6 vectors display a high tropism for striated muscle tissues, the physical constraints of the capsid limit the size of transgenes that can be packaged into transducing virions. To further address the size limitation of rAAV-mediated gene delivery, trans-splicing and recombination approaches have emerged, both of which divide the transgene into relatively equal portions for reconstitution of a larger gene in vivo. Recently, systemic delivery was investigated utilizing the trans-splicing approach with rAAV9 and the alkaline phosphatase reporter transgene.39 Unexpectedly, in this study, the authors observed a reasonable degree of transduction in cardiac tissue but very little in skeletal muscle. This study was conducted to investigate the potential for intravenous administration of rAAV6 recombination vectors to generate a highly functional minidystrophinΔH2–R19 protein body-wide in mdx4cv mouse striated muscles.

Upon evaluation of skeletal musculature of mice treated with the dual recombination vectors, we found considerable transduction of gastrocnemius, quadriceps, and TA muscles approaching that obtained with a single vector expressing microdystrophinΔR4–R23/ΔCT (Figure 3). Although it is difficult to compare relative levels of expression amongst micro-, mini-, and full-length dystrophin-expressing muscles due to enormous differences in western blot gel transfer efficiencies, the immunofluorescence data suggest that the dual-vector approach leads to somewhat lower levels of expression compared with wild-type muscles. The amount of dystrophin generated from rAAV transduced muscles also varied from one muscle type to another, in part due to the relative transduction efficiencies displayed by different muscle groups.28 Because physiological improvements were observed in many aspects of muscle function, we conclude that overall expression levels were in the ranges previously shown to be needed for dystrophin replacement.16 In cardiac tissue, we found the recombination vectors to be somewhat less efficient at transduction compared with the single vector, although this may well be dose dependent. The dual and single vectors were also equally effective at restoring expression of the DGC components α-dystrobrevin-2 and Δ-sarcoglycan (Figure 5a). In the TA muscles, minidystrophinΔH2–R19 expression was observed in ~42% of the myofibers compared with ~73% for microdystrophinΔR4–R23/ΔCT at the dose used. Consistent with these results, dual-vector-generated minidystrophinΔH2–R19 expression protected myofibers from degeneration as indicated by an extremely low level of centrally located nuclei in transduced myofibers (Figure 6c). This level of transduction led to increased peak force generation and muscle mass in the dual-vector-treated muscles relative to that in untreated and microdystrophin-vector-treated muscles (Figure 7a). Interestingly, the minidystrophin-expressing muscles performed better by these assays than did the microdystrophin-expressing muscles despite a lower transduction level, further showing the increased functionality of minidystrophin relative to microdystrophin. This lower transduction level may account for the increased TA muscle mass relative to what we have observed previously in transgenic mdx mice expressing minidystrophin in a uniform manner, although this difference might also be explained by initiation of minidystrophin expression pre- versus postnatally.16 The increased muscle mass in minidystrophin-expressing muscles actually led to a lower specific force generating capacity relative to microdystrophin-expressing muscles. However, the overall increase in peak force coupled with the larger muscle size indicates that the minidystrophin-expressing muscles are relatively more robust. Indeed, mdx4cv muscles expressing minidystrophin were more resistant to contraction-induced injury than either microdystrophin-expressing mdx4cv or mdx4cv muscles (Figure 7c).

Classical HR requires a break or nick in DNA followed by the single-stranded DNA invasion of a homologous double-stranded DNA molecule, annealing of complementary sequences, formation of a Holliday junction via branch migration, and adjacent sequence isomerization. Further, HR can be defined based on the location of the homologous sequences that interact with each other, such as allelic positions on homologous chromosomes, on sister chromatids, within the same chromatid, or on heterologous chromosomes—all mediated by XRCC2, XRCC3, the Mre11/Rad50/NBS1 complex, Rad51, DNA polymerases, ligases, etc.40 In eukaryotes, genetic recombination is essential for proper chromosome segregation during meiosis and to provide a pathway for the repair of damaged DNA. It is thought that rAAV with its ability to induce DNA damage responses upon infection41 could be exploited to facilitate intermolecular recombination events between input viral genomes. Here, the recombination processing of rAAV genomes in skeletal muscle was assessed by Southern analysis using total DNA obtained from TA muscles of mice injected with rAAV6/minidystrophinΔH2–R19 recombination vectors. The analysis revealed a variety of molecular forms along with strong diagnostic bands derived from recombination of the input minidystrophinΔH2–R19 sequences (Figure 2e, A and B) consistent with the transduction efficiency observed in the TA muscles (Figure 6b). In addition to double-stranded HR, previous studies have suggested a role of single-stranded annealing, as an alternative mechanism toward rAAV genome intermediates.13 In this study, given the single-stranded genome packaging of either polarity, we cannot exclude the possibility of single-stranded annealing occurring prior to the conversion of single- to double-stranded rAAV genomes, and thus influencing minidystrophin reconstitution. Likewise, it is not definitively known whether generation of reconstituted genomes forms circular or linear products. As is often the case with rAAV, we suggest it likely that both linear and circular concatameric products exist. However, rAAV genome circularization via HR has several advantages. For example, within muscle, double-stranded circular rAAV genomes display persistent transcriptional activity; as well they do not result in significant chromosomal integrants. Previous efforts have shown an enhancement of directional intermolecular rAAV genome recombination with the use of nonhomologous ITRs.42 This observation suggests a competition between ITR:ITR recombination and intergenic recombination, which is an area of future research that could be exploited to enhance intravascular methods of dual-vector gene delivery.

There are likely to be a number of methodological enhancements to these delivery strategies that can increase the efficiency of recombination events between co-delivered rAAV genomes. Nonetheless, this study has shown that a modest intravenous dose of rAAV6/minidystrophinΔH2–R19 recombination vectors resulted in improving myofiber stability and physiological performance within limb muscles similar to that obtained with an equivalent dose of rAAV6/microdystrophinΔR4–R23/ΔCT. Thus, we have demonstrated the legitimacy of systemic delivery for the dual rAAV vector approach to generate a highly functional minidystrophinΔH2–R19 transgene using rAAV6, which in turn may facilitate the development of improved delivery protocols and therapeutic transgene cassettes useful for DMD gene therapy.

Materials and Methods

MinidystrophinΔH2–R19 recombination vector cloning and virus production. The minidystrophinΔH2–R19 transgene was engineered to be divided approximately equally between two rAAV vg with a 372 base pair region of sequence overlap. Briefly, within the ITRs the first recombination vector contained the cytomegalovirus promoter/enhancer region followed by the upstream portion of the minidystrophinΔH2–R19 transgene encoding the amino-terminal actin-binding domain, hinge-1, the first three spectrin-like repeats, hinge-3, spectrin-like repeat 20 with conclusion in exon 53 at nucleotide 7,980 of the human dystrophin complementary DNA (cDNA) sequence (base 1 of our cDNA is nucleotide 209 of GenBank accession #M18533.1). The genome in this vector is 3.9 kb. The second or downstream vector was designed to initiate within exon 51 (coding for hinge-3) at nucleotide position 7,608 of our human dystrophin cDNA including spectrin-like repeats 20–24 followed by the cysteine-rich (β-dystroglycan binding) domain and terminating within exon 79 precisely at nucleotide 11,564 allowing the inclusion of the full carboxy-terminal domain. Following the transgene is the short rabbit β-globin polyadenylation signal.43 The genome in this vector is 4.8 kb. This design allows for a separation of transcriptional initiation and processing events, ensuring that only those genomes having undergone the correct intermolecular recombination event will yield the desired protein. The final genome size of a correctly recombined vector is predicted to be 7.3 kb. The production of the dual rAAV6 vectors to generate minidystrophinΔH2–R19 and microdystrophinΔR4–R23/ΔC vectors was as previously described.44

Animal experiments. Male wild-type C57Bl/6J and mdx4cv mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME; n = 4) were utilized for all studies except for the intramuscular injections studies, which had n = 3. All animals were experimentally manipulated in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Washington. To address “proof of principle” for minidystrophinΔH2–R19 reconstitution in early pilot experiments, 3-week-old dystrophic mdx4cv mice received either 1 × 1010 vg of each rAAV6 vector in 30 µl (total volume, whether one or two vectors were administered) by intramuscular administration of the TA or 2 × 1012 vg intravenously via the tail vein (300 µl total volume), and were evaluated at 6 weeks of age.

These experiments were then followed by treatment of a larger cohort of 3-week-old dystrophic mdx4cv mice that received 2 × 1012 vg of the dual rAAV6 vectors or the microdystrophin vector, in a single 300 µl bolus delivered intravenously. The TA muscles of these mice were evaluated in situ at 5 months of age for physiological performance subsequent to the mice being terminated for sample collection and further assay evaluation.

PCR recombination analysis of HT1080 cells following AAV infection. To analyze the efficiency of rAAV-minidystrophin overlapping vectors in vitro, we used the human fibrosarcoma cell line HT1080. Briefly, cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 µg/ml). Cells were plated at a density of 5 × 105 cells per 60-mm plate on the day of infection. Immediately before the infection, cells were washed with serum-free medium. AAV infection was then performed in serum-free medium at a multiplicity of infection of 10,000 viral genomes/cell for each virus. At 1 hour postinfection, the final concentration of fetal bovine serum was increased to 10% by the addition of serum. Cell cultures were collected by trypsinization and standard phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) washing 48 hours postinfection. DNA was extracted followed by PCR amplification of 200 ng of total DNA for each sample using the oligonucleotides previously described to allow distinction of recombined products. As an additional control, we included DNA samples obtained from single overlapping vectors and adding these together in a PCR reaction (5′ + 3′).

DNA analysis for detection of rAAV6/minidystrophinΔH2–R19 recombinant genomes in vivo. Total genomic DNA was extracted from muscle tissue by a standard phenol–chloroform method. PCR analysis was performed using primers that hybridized to regions upstream (5′), downstream (3′), and within the homology region (5′/3′). The upstream primer pair annealed to human dystrophin in the context of the full-length cDNA at positions 1,180−1,199 (5′-GGCCGGGTTGGTAATATTCT-3′) and 1,688–1,669 (5′-CGTTGCCATTTGAGAAGGAT-3′). The downstream primer pair was designed to anneal to minidystrophinΔH2–R19 located at positions 8,023−8,042 (5′-AAAAGGGTGAGTGAGCGAGA-3′) and 8,563–8,544 (5′-ATTCCCTCTTGAAGGCCCTA-3′) of the full-length cDNA sequence. Lastly, a recombination primer pair specific to the region of homology, because of the unique junction (R3–H3), anneals to minidystrophinΔH2–R19 cDNA at positions 1,993–2,000 (R3-specific sequence), and 7,269–7,280 (H3-specific sequence) (5′-ATTTCACAGCAGCCTGACCT-3′, where the underlined portion is the H3 region) and 7,825–7,806 (5′-CCTCCTTCCATGACTCAAGC-3′). Thus, a 564 base pair product would be generated if recombination occurred between the two rAAV vectors at the region of homology to yield the minidystrophinΔH2–R19 product found in the parental minidystrophin plasmid. The PCR reaction contained 5 pmol/l of each primer and 20 ng of DNA extracted from one TA. PCR amplification was conducted for 30 cycles under standard conditions (denaturation at 94 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 55 °C for 30 seconds, and elongation at 72 °C for 1 minutes). As a positive control, we used DNA extracted from HT1080 cells infected with a lentivirus encoding minidystrophinΔH2–R19 at a multiplicity of infection of 10.

Southern blot analysis was performed as previously described45 to allow molecular characterization of rAAV vg in transduced muscle tissue. Briefly, 10 µg of total DNA was digested overnight with Bsu36I and BamHI. This enzyme pair cleaves the recombined minidystrophinΔH2–R19 vector genome twice (once in each independent rAAV vector) for Bsu36I or once within the upstream vector followed by twice in the downstream vector when using BamHI. An additional separate digestion with BglII resulted in cleaving the upstream and downstream vectors three and two times, respectively. Digestion in this manner allows evaluation of a multitude of circular and linear concatamerized rAAV forms present in skeletal muscle (Figure 1b). Digested DNA was separated on 0.9% agarose gel and transferred onto nylon membrane (ZetaProbe; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Blots were hybridized with radioactive minidystrophinΔH2–R19 sequence-specific probes to allow detection of viral genomes consisting of either the downstream vector or to the region of homology between the two individual vectors. The minidystrophin probes were prepared by PCR amplification of the minidystrophinΔH2–R19 cDNA sequence spanning nucleotides 8,626–9,526 for the 3′-downstream probe, and 7,608–7,980 for the 5′/3′-recombined probe. Standard methods were used for random-primed DNA synthesis probe generation (Rediprime II; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Signals were detected by radioautograph (2-day exposure shown).

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and western blots. Snap frozen TA muscles previously injected intramuscularly with minidystrophin overlapping vectors (either individually or in tandem) at 1 × 1010 vg were used for western analysis. Muscles were homogenized in standard radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer with the inclusion of 1%/volume protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Protein concentration was determined (BCA assay; Pierce, Rockford, IL) and samples were immediately suspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer containing dithiothreitol (100 mmol/l), sodium dodecyl sulfate (2%), Tris-base (80 mmol/l; pH 6.8), glycerol (12.5%), and bromophenol blue (0.025%) and were stored at −80 °C. Samples containing 25 µg of total protein were loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel (4–20% gradient) and run at constantly at 160 V. Gels were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane using standard 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid buffer (350 mA, 2 hours), which was then blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline-Tween followed by immunoblotting with appropriate antibodies against dystrophin and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (used as a loading control). Dystrophin (MANEX1011b clone 1C7, DSHB, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa), a dystrophin polyclonal antibody against the C-terminal domain46 and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Sigma Aldrich) antibodies were applied at dilutions of 1:20, 1:1,500, and 1:50,000, respectively. Detection was performed with the ECL kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) using either a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated donkey anti-mouse or donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody 1:30,000; (The Jackson Laboratory). All gels contained muscle samples from normal age-matched control mice and untreated mdx4cv mice.

Histological analyses. Following functional analyses, mice were killed by cervical dislocation and a necropsy was performed. Muscles were frozen in liquid-nitrogen-cooled isopentane embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT medium (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA), and sectioned transversely in a cryostat at 10 µm thickness. For immunofluorescence studies, sections were blocked in 4% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% Tween-20 in 1× Dulbecco's PBS (Invitrogen GIBCO, Grand Island, NY). Sections were then washed three times in 1× PBS for 5 minutes. The slides were then followed with an incubation of 60 minutes using rabbit antidystrophin polyclonal antibody (1:700), and rat anti-B2 laminin (1:800) (Sigma Aldrich) in PBS containing 2% goat serum. The sections were rinsed three times in PBS and incubated for 45 minutes with goat anti-rabbit-alexa-488 (1:1,200) and goat anti-rat-alexa-540 (1:800) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The sections were then mounted in antifade mounting media containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Fluorescent sections were imaged using a Nikon eclipse E1000 fluorescent microscope (Nikon, New York, NY). Immunofluorescence detection of representative components of the DGC was performed on TA muscles with primary rabbit polyclonal antibodies to α-dystrobrevin-2 (1:200) and δ-sarcoglycan (1:5,000) (kindly provided by Stan Froehner, University of Washington and Vincenzo Nigro, University of Milan, respectively). For localization of minidystrophinΔH2–R19 and microdystrophinΔR4–R23/ΔCT at myotendinous junctions confocal microscopy was performed on longitudinal gastrocnemius cryosections with immunofluorescent labeling of dystrophin as described above with the exception of utilizing 50% glycerol in PBS as mounting media. Visualization was performed on a Zeiss 510 Meta using ×40 magnification. Images were taken with the same settings and were processed in an identical way. Limits were placed and maintained throughout image processing on the image “gain” to ensure avoidance of immunofluorescence saturation of the images. For bright-field microscopy, sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and mounted with Permount (Fisher Scientific, Fairlong, NJ). Images were captured using a QIcam digital camera and processed using Qcapture Pro (Qimaging, Surrey, British Columbia, Canada).

Myofibers with centrally located nuclei were quantified from dystrophin-positive myofibers in TA muscles by counting fibers in a minimum of four random fields (~800 myofibers/cohort). The mean number of centrally nucleated fibers was compared between treated and untreated mdx4cv mice using an unpaired Student's t-test.

Contractility assays. Mice were anesthetized with 2,2,2-tribromoethanol (Sigma Aldrich) with the TA muscle assayed in situ 20 weeks following intravenous vector administration for force generation and susceptibility to eccentric contraction-induced injury using equipment and protocols described previously.28,44 Wild-type and mdx4cv mice at 5 months of age were used as controls. The conditions established with this assay occur over a broad range of physiological operating conditions with the potential to produce injurious overload of the contractile apparatus.47 The maximum isometric force-producing capacity at optimal muscle fiber length was determined followed by the TA muscle being subjected to a series of progressively greater (5%) length changes under maximum stimulation (lengthening contractions) at 20-second intervals. The impact of each lengthening contraction upon force production was recorded from the peak isometric force generated just prior to the initiation of the subsequent lengthening contraction.

Statistics. All results are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise stated. Differences identified between cohorts were determined using one-way analysis of variance with a Tukey post-test that compares all data sets with a Student's t-test. All data analyses were performed using the PRISM software (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Table S1. Summary of the expected sizes (kb) of bands in Southern blot analysis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AR40864 and AG033610 to J.S.C.). G.L.O. was supported by a National Institutes of Health National Research Service Award (T32 HL07828) and a Development Grant from the Muscular Dystrophy Association (USA). P.G. was supported by a Development Grant from the Muscular Dystrophy Association (USA).

Supplementary Material

Summary of the expected sizes (kb) of bands in Southern blot analysis.

REFERENCES

- Berns KI. Parvovirus replication. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:316–329. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.3.316-329.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiorini JA, Wiener SM, Owens RA, Kyöstió SR, Kotin RM., and, Safer B. Sequence requirements for stable binding and function of Rep68 on the adeno-associated virus type 2 inverted terminal repeats. J Virol. 1994;68:7448–7457. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7448-7457.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JH, Zolotukhin S., and, Muzyczka N. Sequence requirements for binding of Rep68 to the adeno-associated virus terminal repeats. J Virol. 1996;70:1542–1553. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1542-1553.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder RO, Im DS, Ni T, Xiao X, Samulski RJ., and, Muzyczka N. Features of the adeno-associated virus origin involved in substrate recognition by the viral Rep protein. J Virol. 1993;67:6096–6104. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6096-6104.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzyczka N. Use of adeno-associated virus as a general transduction vector for mammalian cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;158:97–129. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-75608-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samulski RJ, Chang LS., and, Shenk T. Helper-free stocks of recombinant adeno-associated viruses: normal integration does not require viral gene expression. J Virol. 1989;63:3822–3828. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3822-3828.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Yue Y, Yan Z, McCray PB., Jr, and, Engelhardt JF. Polarity influences the efficiency of recombinant adenoassociated virus infection in differentiated airway epithelia. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2761–2776. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.18-2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Sharma P, Yang J, Yue Y, Dudus L, Zhang Y, et al. Circular intermediates of recombinant adeno-associated virus have defined structural characteristics responsible for long-term episomal persistence in muscle tissue. J Virol. 1998;72:8568–8577. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8568-8577.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Yan Z, Yue Y., and, Engelhardt JF. Structural analysis of adeno-associated virus transduction circular intermediates. Virology. 1999;261:8–14. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent-Lacaze N, Snyder RO, Gluzman R, Bohl D, Lagarde C., and, Danos O. Structure of adeno-associated virus vector DNA following transduction of the skeletal muscle. J Virol. 1999;73:1949–1955. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1949-1955.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Yue Y., and, Engelhardt JF. Consequences of DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit deficiency on recombinant adeno-associated virus genome circularization and heterodimerization in muscle tissue. J Virol. 2003;77:4751–4759. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4751-4759.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Laipis PJ, Berns KI., and, Flotte TR. Effect of DNA-dependent protein kinase on the molecular fate of the rAAV2 genome in skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4084–4088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061014598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi VW, McCarty DM., and, Samulski RJ. Host cell DNA repair pathways in adeno-associated viral genome processing. J Virol. 2006;80:10346–10356. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00841-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki K, Ma C, Storm TA, Kay MA., and, Nakai H. The role of DNA-PKcs and artemis in opening viral DNA hairpin termini in various tissues in mice. J Virol. 2007;81:11304–11321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01225-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donsante A, Miller DG, Li Y, Vogler C, Brunt EM, Russell DW, et al. AAV vector integration sites in mouse hepatocellular carcinoma. Science. 2007;317:477. doi: 10.1126/science.1142658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper SQ, Hauser MA, DelloRusso C, Duan D, Crawford RW, Phelps SF, et al. Modular flexibility of dystrophin: implications for gene therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Med. 2002;8:253–261. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Lillicrap D, Patarroyo-White S, Liu T, Qian X, Scallan CD, et al. Multiyear therapeutic benefit of AAV serotypes 2, 6, and 8 delivering factor VIII to hemophilia A mice and dogs. Blood. 2006;108:107–115. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-5115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks GB, Combs AC, Chamberlain JR., and, Chamberlain JS. Molecular and cellular adaptations to chronic myotendinous strain injury in mdx mice expressing a truncated dystrophin. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3975–3986. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England SB, Nicholson LV, Johnson MA, Forrest SM, Love DR, Zubrzycka-Gaarn EE, et al. Very mild muscular dystrophy associated with the deletion of 46% of dystrophin. Nature. 1990;343:180–182. doi: 10.1038/343180a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Yue Y., and, Engelhardt JF. Expanding AAV packaging capacity with trans-splicing or overlapping vectors: a quantitative comparison. Mol Ther. 2001;4:383–391. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Yue Y., and, Engelhardt JF. Dual vector expansion of the recombinant AAV packaging capacity. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;219:29–51. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-350-x:29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Yue Y, Yan Z., and, Engelhardt JF. A new dual-vector approach to enhance recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated gene expression through intermolecular cis activation. Nat Med. 2000;6:595–598. doi: 10.1038/75080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Yue Y, Yan Z., and, Engelhardt JF. Trans-splicing vectors expand the packaging limits of adeno-associated virus for gene therapy applications. Methods Mol Med. 2003;76:287–307. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-304-6:287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Yue Y., and, Duan D. Viral serotype and the transgene sequence influence overlapping adeno-associated viral (AAV) vector-mediated gene transfer in skeletal muscle. J Gene Med. 2006;8:298–305. doi: 10.1002/jgm.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Yue Y, Lai Y., and, Duan D. A hybrid vector system expands adeno-associated viral vector packaging capacity in a transgene-independent manner. Mol Ther. 2008;16:124–130. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Yue Y, Long C, Bostick B., and, Duan D. Efficient whole-body transduction with trans-splicing adeno-associated viral vectors. Mol Ther. 2007;15:750–755. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbert CL, Allen JM., and, Miller AD. Efficient mouse airway transduction following recombination between AAV vectors carrying parts of a larger gene. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:697–701. doi: 10.1038/nbt0702-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorevic P, Blankinship MJ, Allen JM, Crawford RW, Meuse L, Miller DG, et al. Systemic delivery of genes to striated muscles using adeno-associated viral vectors. Nat Med. 2004;10:828–834. doi: 10.1038/nm1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidball JG. Myotendinous junction injury in relation to junction structure and molecular composition. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1991;19:419–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorevic P, Allen JM, Minami E, Blankinship MJ, Haraguchi M, Meuse L, et al. rAAV6-microdystrophin preserves muscle function and extends lifespan in severely dystrophic mice. Nat Med. 2006;12:787–789. doi: 10.1038/nm1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bish LT, Sleeper MM, Brainard B, Cole S, Russell N, Withnall E, et al. Percutaneous transendocardial delivery of self-complementary adeno-associated virus 6 achieves global cardiac gene transfer in canines. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1953–1959. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allocca M, Doria M, Petrillo M, Colella P, Garcia-Hoyos M, Gibbs D, et al. Serotype-dependent packaging of large genes in adeno-associated viral vectors results in effective gene delivery in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1955–1964. doi: 10.1172/JCI34316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y, Yue Y., and, Duan D. Evidence for the failure of adeno-associated virus serotype 5 to package a viral genome > or = 8.2 kb. Mol Ther. 2010;18:75–79. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B, Nakai H., and, Xiao W. Characterization of genome integrity for oversized recombinant AAV vector. Mol Ther. 2010;18:87–92. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Yang H., and, Colosi P. Effect of genome size on AAV vector packaging. Mol Ther. 2010;18:80–86. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CE, Storm TA, Huang Z., and, Kay MA. Rapid uncoating of vector genomes is the key to efficient liver transduction with pseudotyped adeno-associated virus vectors. J Virol. 2004;78:3110–3122. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.3110-3122.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz BR., and, Chamberlain JS. Recombinant adeno-associated virus transduction and integration. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1189–1199. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks GB, Judge LM, Allen JM., and, Chamberlain JS. The polyproline site in hinge 2 influences the functional capacity of truncated dystrophins. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Yue Y, Shin JH., and, Duan D. Systemic trans-splicing adeno-associated viral delivery efficiently transduces the heart of adult mdx mouse, a model for duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:1319–1328. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Driscoll M., and, Jeggo PA. The role of double-strand break repair—insights from human genetics. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:45–54. doi: 10.1038/nrg1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurvansuu J, Raj K, Stasiak A., and, Beard P. Viral transport of DNA damage that mimics a stalled replication fork. J Virol. 2005;79:569–580. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.569-580.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Lei-Butters DC, Zhang Y, Zak R., and, Engelhardt JF. Hybrid adeno-associated virus bearing nonhomologous inverted terminal repeats enhances dual-vector reconstruction of minigenes in vivo. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:81–87. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil A., and, Proudfoot NJ. Position-dependent sequence elements downstream of AAUAAA are required for efficient rabbit β-globin mRNA 3′ end formation. Cell. 1987;49:399–406. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankinship MJ, Gregorevic P, Allen JM, Harper SQ, Harper H, Halbert CL, et al. Efficient transduction of skeletal muscle using vectors based on adeno-associated virus serotype 6. Mol Ther. 2004;10:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue N., and, Russell DW. Packaging cells based on inducible gene amplification for the production of adeno-associated virus vectors. J Virol. 1998;72:7024–7031. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7024-7031.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafael JA, Cox GA, Corrado K, Jung D, Campbell KP., and, Chamberlain JS. Forced expression of dystrophin deletion constructs reveals structure-function correlations. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:93–102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafael JA, Tinsley JM, Potter AC, Deconinck AE., and, Davies KE. Skeletal muscle-specific expression of a utrophin transgene rescues utrophin-dystrophin deficient mice. Nat Genet. 1998;19:79–82. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Summary of the expected sizes (kb) of bands in Southern blot analysis.