Abstract

Background

Although COPD is a common cause of death and disability, little is known about the effects of socioeconomic status (SES) and race-ethnicity on health outcomes.

Methods

We aimed to determine the independent impacts of SES and race-ethnicity on COPD severity status, functional limitations, and acute exacerbations of COPD among patients with access to health care. Data were used from the FLOW cohort study of 1,202 Kaiser Permanente Northern California Medical Care Plan members with COPD.

Results

Lower educational attainment and household income were consistently related to greater disease severity, poorer lung function, and greater physical functional limitations in cross-sectional analysis. Black race was associated with greater COPD severity, but these differences were no longer apparent after controlling for SES variables and other covariates (comorbidities, smoking, body mass index, and occupational exposures). Both lower education and income were independently related to a greater prospective risk of acute COPD exacerbation (HR 1.5; 95% CI 1.01 to 2.1; and HR 2.1; 95% CI 1.4 to 3.4, respectively).

Conclusion

Low SES is a risk factor for a broad array of adverse COPD health outcomes. Clinicians and disease management programs should consider SES as a key patient-level marker of risk for poor outcomes.

Socioeconomic status (SES) has a profound impact on health and longevity.[1] Studying this question, especially in the U.S. context, has been complicated by the potential interrelationships between SES and race-ethnicity. In pulmonary medicine, numerous studies have shown that lower SES and black race are both associated with worse outcomes in asthma, including respiratory symptoms, hospitalizations, and mortality.[2–7] Although COPD is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States, much less is known about the impact of SES and race-ethnicity on health outcomes.[8–17]

The interplay between race-ethnicity, SES, and COPD health outcomes remains poorly characterized.[8–17] Studies have examined the association between race and health-related quality of life, hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and mortality in COPD with mixed results.[12–18] We have previously found that lower socioeconomic status is associated with a lower use of tiotropium for COPD, whereas race was not.[19] Our study aims to elucidate the impacts of race-ethnicity and SES on COPD health outcomes.

A major factor that can confound the relationships among SES, race-ethnicity, and health outcomes is access to health care. The FLOW (Function, Living, Outcomes, and Work) cohort study of COPD, which recruited Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Plan members, provides an opportunity to study how SES and race-ethnicity influence health outcomes among patients with broad access to health care. In this study, we elucidated the independent and combined impacts of SES and race-ethnicity on COPD severity, physical functional limitations, and acute exacerbations of COPD.

METHODS

Overview

The FLOW study of COPD is an ongoing prospective cohort study of adult members of an integrated health care delivery system with a physician’s diagnosis of COPD. The long-term goal is to determine what factors are responsible for the development of disability in COPD. At baseline assessment, we conducted structured telephone interviews that ascertained COPD-related health status, clinical history, and sociodemographic characteristics (conducted between 1/27/2005 and 2/3/2007). Research clinic visits included spirometry and other physical assessments (conducted between 2/3/2005 and 3/31/2007). In this report, we evaluated the cross-sectional impact of race and SES on COPD severity and physical functional limitations and the longitudinal impact on the risk of COPD exacerbation. The study was approved both by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research and the Kaiser Foundation Research Institute’s institutional review board and all participants provided written informed consent.

Subject recruitment

We studied adult members of Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program (KPMCP), the nation’s largest non-profit managed care organization. In Northern California, the KPMCP provides the full spectrum of primary-to-tertiary care to approximately 3.2 million members. In Northern California, KPMCP’s share of the regional population ranges from 25 to 30%.[20] The demographic characteristics of KPMCP members are similar to the overall Northern California population, except for the extremes of income distribution.[21]

Recruitment methods have been previously reported in detail.[22, 23] We used KPMCP databases to identify all adult KPMCP members who were recently treated for COPD using a previously described approach. The age range was restricted to 40–65 years because a key study outcome includes work disability.[24] Using KPMCP computerized databases, we identified all subjects who met both of two criteria: one based on health care utilization and the second based on medication prescribing. The health care utilization criterion was one or more ambulatory visits, emergency department visits, or hospitalizations with a principal International Classification of Disease (ICD-9) diagnosis code for COPD (chronic bronchitis [491], emphysema [492], or COPD [496] during a recent 12 month time period. The medication criterion was two or more prescriptions for a COPD-related medication during a 12 month window beginning 6 months before the index utilization date and ending 6 months after index date. Based on medical record review, we demonstrated that this algorithm is a valid method for identifying adults with COPD.[24]

A total of 5,800 subjects were initially identified using the computerized algorithm. Of these, 298 died before they could be recruited into the study. Another 1,011 did not meet study inclusion criteria or were excluded at the time of interview contact as noted above. The completion rate for structured telephone interviews was 2,310 out of a remaining eligible group of 4,491 (51%). This is comparable to our earlier cohort study of adult asthma conducted at KPMCP and compares favorably to other survey-based epidemiologic studies conducted in the U.S.[25, 26] Among the 2,310 respondents, 112 were not eligible for the clinic visit and 1,216 completed the research clinic visit (55% of those interviewed and eligible). An additional 10 subjects were excluded because they did not meet the GOLD criteria for COPD after interviews and spirometry were performed.[27] Four additional subjects were excluded from this analysis because they could not perform spirometry due to previous tracheostomy placement. Ultimately, there were 1,202 subjects with COPD who completed both interviews and research clinic visits.

We compared interviewed to non-interviewed subjects using demographic information obtained from Kaiser computerized databases for subjects who did not complete interviews. Compared to subjects who were eligible but not interviewed, interviewed subjects were slightly older (by 0.7 years on average), more likely to be female (59 vs. 51%), and more likely to be white (69 vs. 56%). In terms of race-ethnicity, the two largest minority subgroups were slightly over-represented among those who completed interviews: (Black / African American 14% vs. 11%, Hispanic 9% vs. 4%). Most of the differences in race were driven by limitations inherent in the Kaiser computerized databases: the prevalence of unknown race was much higher among those who did not complete interviews (17% vs 0.3%).

We also compared characteristics of subjects who did and did not complete the research clinic visit. Compared to subjects who completed interviews but not the clinic visit, clinic visit attendees were similar in age (mean difference 0.3 years), gender (58% vs. 55% female), and race-ethnicity (67 vs. 61% white). We were highly successful recruiting persons of Black or Hispanic background for the research clinic visit (17% completed vs. 11% not completed and 9 vs. 5%, respectively).

Socioeconomic status and race-ethnicity

Each subject underwent a 30–40 minute structured telephone interview that used customized computer-assisted telephone interview software. Based on our previous work and consistent with standard approaches, we defined SES using both educational attainment and annual household income. Educational attainment was defined as high school or less, some college, or college / graduate degree.[22, 23, 28] Using cut-off points consistent with the study population, annual household income was defined as low (<$20,000), medium ($20–80,000), high (>$80,000), or not reported. [22, 23] Race-ethnicity was defined based on self-report as a series of categories: white / non-Hispanic, Black, Asian or Pacific Islander, Hispanic or Latino, and other. The “other” group includes groups with very small numbers, such as Native American, and persons who declined to report their race-ethnicity. This race-ethnicity scheme was defined to be consistent with the United States Census Bureau, which conceptualizes race and ethnicity as separate entities.

Study outcomes: COPD severity

We used a combined approach to measure COPD severity. We used a disease-specific COPD severity score that we had previously developed and validated for use in epidemiologic and outcomes research.[29] Based on survey responses, the COPD severity score is comprised of five overall aspects of COPD severity: respiratory symptoms, systemic corticosteroid use, other COPD medication use, previous hospitalization or intubation for respiratory disease, and home oxygen use. Each item was weighted based on clinical aspects of the disease and its expected contribution to overall COPD severity. Possible total scores range from 0 to 35, with higher scores reflecting more severe COPD.

We also used the validated BODE Index, which is a multi-modal measure of disease severity.[30] The BODE Index is based on the body-mass index (B), the degree of airflow obstruction (O) measured by Forced Expiratory Volume in one second (FEV1), grade of dyspnea (D) assessed by the modified Medical Research Council (MRC) Dyspnea Scale , and exercise capacity (E) measured by the six-minute-walk test. Each component is assigned a specific score and the total score ranges from 0 to 10 points (higher scores indicate greater severity). The BODE index predicts death and other poor outcomes in COPD.[30–32] We have shown elsewhere that the BODE and COPD severity score instruments provide independent explanatory power in relation to disease status.[33]

Study outcomes: pulmonary function impairment

To assess respiratory impairment, we conducted spirometry according to American Thoracic Society (ATS) Guidelines.[34, 35] We used the EasyOne™ Frontline spirometer (ndd Medical Technologies, Chelmsford, MA), which is known for its reliability, accuracy, and durability.[36, 37] Percent predicted values were calculated using the race-ethnicity specific predictive equations derived from NHANES III.[38] We also report the ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity because it indicates the degree of airflow obstruction.

Study outcomes: physical functional limitations

We examined two physical functional limitations, which are basic decrements in basic physical actions (e.g., mobility or strength). Submaximal exercise performance was measured using the Six Minute Walk Test, which was developed by Guyatt and has been widely used in studies of COPD.[39, 40] We used a standardized flat, straight course of 30 meters in accordance with American Thoracic Society (ATS) Guidelines.[41] Subjects who routinely used home oxygen or who had a resting oxygen saturation < 90% were supplied with supplemental oxygen during the test. Every two minutes, the technician used standardized phrases to encourage effort, as recommended by the ATS guidelines. The primary outcome was the total distance walked in 6 minutes.

Lower extremity function was measured using the validated Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).[42–44] The battery includes 3 performance measures, each scored from 0 to 4 points. The standing balance test asks subjects to maintain their feet in a side-by-side, semi-tandem stand (heel of one foot next to the big toe of the other foot), or tandem stand (heel of one foot directly in front of the other foot) for 10 seconds. The maximum score of 4 is assigned for maintaining the tandem stand for 10 seconds; a low score of 1 is assigned for side-by-side standing for 10 seconds, with inability to hold a semi-tandem position for 10 seconds. A test of walking speed requires subjects to walk 4 meters at their normal pace. Participants are assigned a score from 1 to 4 based on the quartile of length of time needed to complete the test. The chair stand test, which reflects lower extremity extensor muscle strength, measures the time required for the subject to stand up and sit down from a chair 5 times with arms folded across the chest. The chair height is standardized for all subjects. Scores from 1 to 4 are assigned based on quartile of length of time to complete the task. A summary performance score integrates the 3 performance measures, ranging from 0 to 12. Previous work indicates that the battery has excellent inter-observer reliability, test-retest reliability, and predictive validity.[42–44]

Longitudinal outcomes: acute exacerbation of COPD

We used emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalization for COPD as proxy measures of acute COPD exacerbation. These outcomes were ascertained during prospective follow-up, after completion of baseline interviews. COPD-related hospitalization was defined as those with a principal ICD-9 discharge diagnosis code for COPD (491.xx,492.xx, or 496.xx). COPD-related emergency department (ED) visits were identified as those with an ICD-9 code for COPD. In contrast to hospital discharge diagnoses, ED visits do not distinguish primary or secondary diagnoses in the Kaiser system. A composite outcome for hospital-based care was defined as either an ED visit or hospitalization for COPD. The median duration of follow-up was 2.1 years (25th–75th interquartile range 1.7 to 2.6 years). During the follow-up period, there were 76 hospitalizations and 244 ED visits for COPD.

Covariates

We selected covariates that may be related to race-ethnicity / SES and health outcomes in COPD.[45, 46] These included cigarette smoking, which was measured using questions developed for the National Health Interview Survey.[47] Body mass index was also determined from height and weight measured at the research clinic visit (weight in kilograms / height in meters2). Height was measured by a wall stadiometer in subjects without shoes; weight was measured by a digital scale. Body mass index was categorized into 4 groups using the standard National Heart Lung and Blood Institute / World Health Organization criteria: underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (>30 kg/m2).[48]

Occupational exposures to vapors, gases, dusts, or fumes during the longest held job was ascertained using a validated question derived from the baseline European Community Respiratory Health Survey(ECRHS I). [49, 50] We assessed a series of comorbid health conditions that were related either to COPD or disability using survey items modified from the National Health Interview Survey.[51] These include a reported physician’s diagnosis of sleep apnea, allergic rhinitis, lung cancer, diabetes, arthritis, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease or myocardial infarction, stroke, hypertension, and low back pain. Because there is no consensus for how to measure comorbidity in COPD, we chose to calculate a simple summary score ranging from 0–10 was created from these items. This approach is consistent with earlier work showing that a summary count of comorbidities is more related to physical function than measures such as the Charlson Index, which was designed to predict mortality.[52]

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). The relationship between race-ethnicity category and SES indicators was examined using the chi-square test for categorical variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables.

Our analytic goal was to examine the independent and joint impacts of race-ethnicity and SES on COPD-related health outcomes. We used multivariable linear regression analysis to elucidate the association between race, SES, and health outcomes (COPD severity, pulmonary function impairment, and functional limitations). In the first analysis, we examined the impact of race-ethnicity on severity indicators, controlling for age and sex. In the second model, we included both race-ethnicity and SES indicators to study the independent impacts of each set of variables. Finally, we examined the ‘residual’ impact of race-ethnicity and SES after accounting for personal characteristics and exposures that could be related to both race / SES and COPD outcomes: cigarette smoking, occupational exposures, comorbidities, and body mass index. We conceive of these covariates as easily measured exposures (e.g., cigarette smoking, occupational exposures) or personal characteristics (e.g., body mass index, comorbidities) that may account, in part, for the association between race-ethnicity (or SES) and COPD outcomes.

We used Cox proportional hazards regression to elucidate the impact of race, SES, and other covariates on the prospective risk of COPD exacerbations as defined by hospital-based care for COPD (i.e., composite of ED visits and hospitalizations). The analytic strategy was analogous to the one used above. The proportional hazards assumption was examined by evaluating interaction terms between time and race-ethnicity and SES (p>0.20 in all cases, indicating no violation).

In our theoretical framework, COPD severity, which is measured by the COPD Severity Score and the BODE Index, is on the causal pathway between race-ethnicity, SES, and COPD health outcomes. Therefore, we have not adjusted for COPD severity in analyses that evaluate the impact of race-ethnicity and SES on COPD health outcomes because it would bias the estimates of these parameters.

As a sensitivity analysis, we re-defined smoking history as pack-years of smoking and repeated the analysis. Compared to the primary analysis, there were no substantive differences and, consequently, these data are not reported.

RESULTS

SES and Race-ethnicity

There were marked differences in SES by race-ethnicity category (Table 1). Hispanic subjects were the most likely to have the lowest level of educational attainment, whereas Asian subjects had the highest educational status (Table 1). Black subjects were most likely to have the lowest income category, whereas Asian persons were most likely to be in the highest income category. There were also differences in age and smoking history (Table 1).

Table 1.

Race and socioeconomic status among 1,202 adults with COPD

| White (non-Hispanic) | Black | Hispanic | Asian / Pacific Islander | Other | P value for comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=810 | N=206 | N=111 | N=35 | N=40 | ||

| Age (years) | 58.7 (6.1) | 56.9 (6.2) | 58.6 (6.1) | 56.1 (6.8) | 57.3 (7.0) | 0.001 |

| Female gender | 461 (57%) | 128 (62%) | 59 (53%) | 18 (51%) | 25 (63%) | 0.44 |

| EDUCATION | <0.0001 | |||||

| Less than HS | 237 (29%) | 52 (25%) | 47 (42%) | 3 (9%) | 13 (33%) | |

| Some college | 332 (41%) | 113 (55%) | 45 (41%) | 13 (37%) | 21 (53%) | |

| College degree+ | 241 (30%) | 41 (20%) | 19 (17%) | 19 (54%) | 6 (15%) | |

| INCOME | <0.0001 | |||||

| Low | 65 (8%) | 42 (20%) | 14 (13%) | 1 (3%) | 7 (18%) | |

| Medium | 470 (58%) | 123 (60%) | 69 (62%) | 16 (46%) | 21 (53%) | |

| High | 207 (26%) | 28 (14%) | 8 (7%) | 17 (49%) | 4 (10%) | |

| Missing | 68 (8%) | 13 (6%) | 8 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 8 (20%) | |

| SMOKING | 0.0005 | |||||

| Never smoked | 96 (12%) | 27 (13%) | 20 (18%) | 16 (46%) | 6 (15%) | |

| Current smoker | 269 (33%) | 72 (35%) | 30 (27%) | 6 (17%) | 16 (40%) | |

| Past smoker | 445 (55%) | 107 (52%) | 61 (55%) | 13 (37%) | 18 (45%) |

Proportions are column percentages. All data are n(%) except for age which is mean (standard deviation)

SES, Race-ethnicity, and COPD severity

Lower educational attainment and household income were consistently related to greater COPD severity scores and BODE scores, even after controlling for race-ethnicity and other covariates (comorbidities, smoking, body mass index, and occupational exposures) (Table 2). Black race was associated with greater disease severity, but these differences were no longer apparent after controlling for SES variables and additional covariates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socioeconomic status, race-ethnicity, and COPD severity

| SES Indicator | COPD Severity Score | BODE Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| RACE | ||||||

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Black | 1.5 (0.5,2.4) | 1.0 (0.04,1.9) | 0.7 (−0.2,1.6) | 0.4 (0.03,0.8) | 0.1 (−0.2,0.5) | 0.07 (−0.3,0.4) |

| Asian | −1.5 (−3.5,0.6) | −0.5 (−2.5,1.5) | −0.5 (−2.5,1.5) | −0.2 (−1.1,0.6) | 0.3 (−0.5,1.1) | 0.5 (−0.3,1.2) |

| Hispanic | −0.5 (−1.7,0.7) | −0.9 (−2.1,0.2) | −1.1 (−2.2,0.1) | −0.1 (−0.6,0.4) | −0.3 (−0.8,0.1) | −0.3 (−0.8,0.1) |

| Other | 0.4 (−1.6,2.3) | −0.2 (−2.1,1.6) | −0.4 −2.3,1.4) | 0.4 (−0.3,1.2) | 0.08 (−0.6,0.8) | 0.06 (−0.7,0.8) |

| EDUCATION | ||||||

| Less than HS | N/A | 2.0 (1.0,2.9) | 1.8 (0.9,2.7) | N/A | 1.1 (0.7,1.4) | 1.0 (0.6,1.3) |

| Some college | N/A | 1.4 (0.6,2.3) | 1.3 (0.4,2.0) | N/A | 0.7 (0.4,1.0) | 0.6 (0.3,1.0) |

| College degree+ | N/A | Referent | Referent | N/A | Referent | Referent |

| INCOME | ||||||

| Low | N/A | 3.6 (2.3,4.9) | 3.4 (2.1,4.7) | N/A | 1.9 (1.4,2.4) | 1.7 (1.2,2.2) |

| Medium | N/A | 1.4 (0.5,2.3) | 1.4 (0.5,2.2) | N/A | 0.8 (0.4,1.1) | 0.7 (0.4,1.0) |

| High | N/A | Referent | Referent | N/A | Referent | Referent |

Educational attainment categories are less than high school, some college, college degree or graduate school; income categories are low (<$20,000), medium ($20,000–$80,000), high (>$80,000), and missing.

-Higher COPD severity scores and BODE scores = poorer status

-Multivariable linear regression analysis–all results are mean difference compared to referent group (95% confidence intervals); results with p<0.05 are shown in bold font.

Model 1 = impact of race, adjusting for age and sex

Model 2 = impact of race, educational attainment, and household income, adjusting for age and sex

Model 3= race, educational attainment, and household income, adjusting for age and sex; also including additional covariates (smoking history, occupational exposures on longest held job, body mass index, and co-morbidities–see Methods)

SES, race-ethnicity, and pulmonary function impairment

There was a strong gradient between SES and FEV1% predicted. Lower levels of education and income were related to progressively poorer FEV1% (Table 3). SES was also associated with the degree of airflow obstruction, as measured by FEV1/FVC, but only at the lowest levels of education and income.

Table 3.

Socioeconomic status, race-ethnicity, and pulmonary function impairment in COPD

| SES Indicator | Forced expiratory volume in 1 second % (percent of predicted value) | Forced expiratory volume in 1 second / forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) × 100 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| RACE | ||||||

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Black | 3.5 (−0.03,7.0) | 5.0 (1.5,8.5) | 4.3 (0.8,7.7) | 1.8 (−0.5,4.0) | 2.2 (−0.07,4.5) | 1.2 (−1.0,3.3) |

| Asian | −3.1 (−10.8,4.6) | −5.8 (−14,1.9) | −6.6 (−14.3,1.2) | 3.2 (−1.7,8.2) | 2.1 (−2.9,7.1) | 2.8 (−1.9,7.6) |

| Hispanic | 1.6 (−2.9,6.1) | 3.3 (−1.2,7.8) | 2.5 (−2.0,7.0) | 2.0 (−0.9,4.8) | 2.7 (−0.2,5.7) | 1.8 (−1.0,4.5) |

| Other | 4.3 (−2.9,11.6) | 6.1 (−1.1,13.2) | 4.6 (−2.5,11.7) | 4.3 (−0.3,9.0) | 5.0 (0.4,9.6) | 3.2 (−1.1,7.6) |

| EDUCATION | ||||||

| Less than HS | N/A | −6.2 (−9.8,−2.7) | −5.6 (−9.2,−2.0) | N/A | −3.7 (−6.0,−1.4) | −3.4 (−5.6,−1.2) |

| Some college | N/A | −3.8 (−7.1,−0.6) | −3.7 (−6.9,−0.4) | N/A | −1.4 (−3.4,0.7) | −1.6 (−3.6,0.4) |

| College degree+ | N/A | Referent | Referent | N/A | Referent | Referent |

| INCOME | ||||||

| Low | N/A | −11.3 (−16.2,−6.4) | −12.4 (−17.3,−7.4) | N/A | −3.8 (−0.6,7.0) | −5.9 (−9.0,−2.9) |

| Medium | N/A | −4.7 (−8.0,−1.4) | −4.9 (−8.2,−1.7) | N/A | −0.8 (−3.0,1.3) | −1.5 (−3.5,0.5) |

| High | N/A | Referent | Referent | N/A | Referent | Referent |

Educational attainment categories are less than high school, some college, college degree or graduate school; income categories are low (<$20,000), medium ($20,000–$80,000), high (>$80,000), and missing.

-Respiratory impairment was measured by spirometry (FEV1% is the percent predicted value).

-Multivariable linear regression analysis–all results are mean difference compared to referent group (95% confidence intervals); results with p<0.05 are shown in bold font.

Model 1 = impact of race, adjusting for age, sex, and height

Model 2 = impact of race, educational attainment, and household income, adjusting for age, sex, and height

Model 3= race, educational attainment, and household income, adjusting for age, sex, and height; also including additional covariates (smoking history, occupational exposures on longest held job, body mass index, and co-morbidities)

Black race was associated with higher FEV1% predicted compared to white subjects, even after controlling for SES variables and other covariates (mean increment 4.3%; 95% CI 0.8 to 7.7%) (Table 3). When residuals were calculated for FEV1 based on age, sex, race-ethnicity, and height (observed minus expected values), black race remained associated with higher lung function compared to white subjects (mean residual value for black vs. white = 270 ml; 95% CI 168 to 372 ml). There was no association, however, between race and ratio of FEV1/FVC in the fully adjusted model.

SES, race-ethnicity, and physical functional limitations

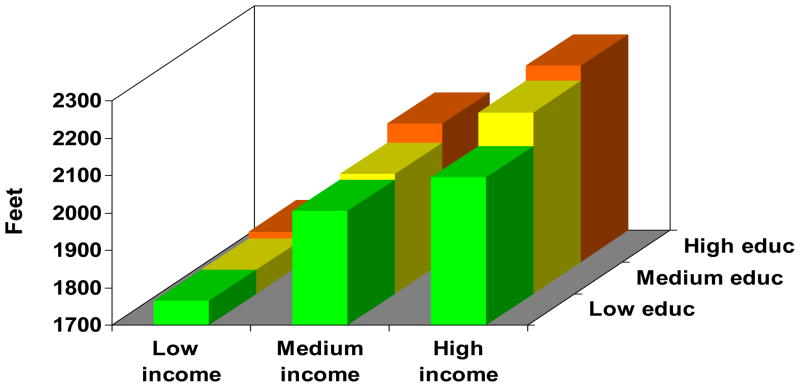

Educational attainment and lower income were consistently and substantively related to poorer distance walked in six minutes and poorer lower extremity function (Table 4). In particular, the lowest income category was associated with a lower distance walked, equivalent to more than one football field in length (−303 feet; 95% CI −380 to −227 feet).

Table 4.

Socioeconomic status, race-ethnicity, and physical functional limitations

| SES Indicator | Distance walked in 6 minutes (feet) | Lower extremity function (points) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| RACE | ||||||

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Black | −126 (−185, −66) | −78 (−136, −21) | −55 (−109, −1) | −0.7 (−1, −0.4) | −0.5 (−0.9, −0.2) | −0.4 (−0.7, −0.1) |

| Asian | 105 (−26,236) | 29 (−97,155) | −34 (−152,85) | 0.5 (−0.2,1.3) | 0.3 (−0.4,1) | 0.1 (−0.6,0.8) |

| Hispanic | 20 (−58,98) | 51 (−24,155) | 56 (−14,126) | 0.1 (−0.3,0.5) | 0.2 (−0.2,0.6) | 0.3 (−0.1,0.6) |

| Other | −147 (−269,−25) | −93 (−209,24) | −57 (−166,52) | −0.3 (−0.1,0.3) | −0.1 (−0.8,0.6) | 0 (−0.6,0.6) |

| EDUCATION | ||||||

| Less than HS | N/A | −108 (−166,−50) | −80 (−135,−25) | N/A | −0.4 (−0.8,−0.1) | −0.4 (−0.7,−0.1) |

| Some college | N/A | −72 (−125,−20) | −40 (−90,10) | N/A | −0.2 (−0.5,0.13) | −0.1 (−0.4,0.2) |

| College degree+ | N/A | Referent | Referent | N/A | Referent | Referent |

| INCOME | ||||||

| Low | N/A | −385 (−466,−304) | −303 (−380,−227) | N/A | −1.5 (−1.9,−1.0) | −1.1 (−1.6,−0.7) |

| Medium | N/A | −136 (−189,−82) | −106 (−156,−66) | N/A | −0.2 (−0.5,0.06) | −0.1 (−0.4,0.1) |

| High | N/A | Referent | Referent | N/A | Referent | Referent |

- Distance walked in 6 minutes was measured by the Six Minute Walk Test; lower extremity function was measured by the Short Physical Performance Battery

-Multivariable linear regression analysis–all results are mean difference compared to referent group (95% confidence intervals); results with p<0.05 are shown in bold font.

Model 1 = impact of race, adjusting for age, sex, and height

Model 2 = impact of race, educational attainment, and household income, adjusting for age, sex, and height

Model 3= race, educational attainment, and household income, adjusting for age, sex, and height; also including additional covariates (smoking history, occupational exposures on longest held job, body mass index, and co-morbidities)

Despite the lung function findings showing relatively greater FEV1%, black race was related to poorer distance walked in 6 minutes (−55 feet; 95% CI −109 to −1 feet) and lower extremity function (−0.4 points; 95% CI −0.7 to −0.1 point) (Table 4). Moreover, controlling for FEV1% increased the decrement in distance walked in 6 minutes for blacks versus whites (−77 feet; 95% CI −128 to −26 feet). The results for race and lower extremity function were unchanged after additional adjustment for lung function.

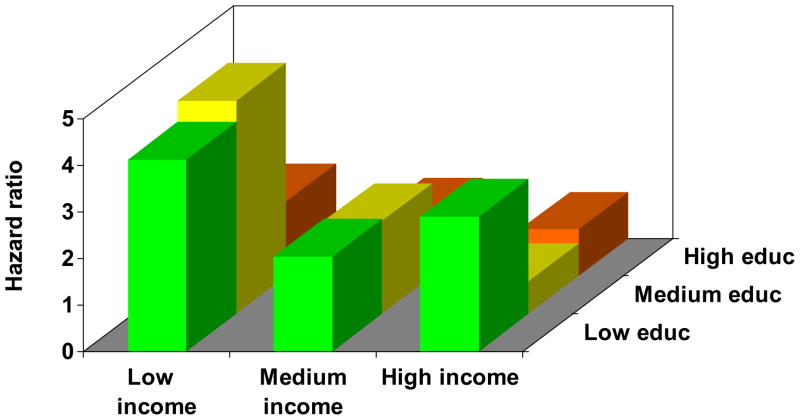

SES, race-ethnicity, and longitudinal risk of acute COPD exacerbations

Low income and educational attainment were independently related to a greater longitudinal risk of acute COPD exacerbation (Table 5). The lowest education category (HR 1.5; 95% CI 1.01 to 2.1) and lowest income class (HR 2.1; 95% CI 1.4 to 3.4) were associated with a greater risk of hospital-based care. Although black race was also associated with a greater prospective risk of acute COPD exacerbations, this no longer persisted after controlling for SES variables and additional covariates (Table 5). A further analysis was conducted to evaluate whether the association between lower SES and the longitudinal risk of COPD exacerbation could be accounted for by the mediating effect of COPD severity. After the COPD Severity Score and BODE score were added to the model, SES was no longer statistically related to COPD exacerbations consistent with a mediating effect of COPD severity.

Table 5.

Prospective impact of socioeconomic indicators on acute exacerbations of COPD requiring hospital-based care

| SES Indicator | Risk of Hospital-based care for COPD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 (mediation model) | |

| RACE | ||||

| White | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Black | 1.4 (1.04,1.9) | 1.2 (0.9,1.7) | 1.2 (0.9,1.6) | 1.2 (0.8,1.6) |

| Asian | 0.4 (0.1,1.2) | 0.5 (0.2,1.5) | 0.6 (0.2,1.9) | 0.5 (0.2,1.5) |

| Hispanic | 0.9 (0.6,1.4) | 0.8 (0.5,1.2) | 0.9 (0.5,1.3) | 1.0 (0.6,1.6) |

| Other | 1.5 (0.8,2.8) | 1.2 (0.6,2.3) | 1.2 (0.6,2.3) | 1.2 (0.6,2.2) |

| EDUCATION | ||||

| Less than high school | N/A | 1.9 (1.3,2.7) | 1.5 (1.01,2.1) | 1.1 (0.7,1.6) |

| Some college | N/A | 1.5 (1.1,2.1) | 1.2 (0.9,1.7) | 1.0 (0.7,1.4) |

| College degree or some graduate school | N/A | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| INCOME | ||||

| Low (<$20k) | N/A | 2.9 (1.8,4.5) | 2.1 (1.4,3.4) | 1.5 (0.9,2.4) |

| Medium ($20–80k) | N/A | 1.4 (0.96,2.0)* | 1.2 (0.9,1.8) | 1.0 (0.7,1.5) |

| High (>$80k) | N/A | Referent | Referent | Referent |

p=0.084

Hospital-based care = emergency department visit or hospitalization for COPD from Kaiser Permanente Northern California computerized databases (see Methods)

-Multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis - all results are hazard ratios compared to referent group (95% confidence intervals); results with p<0.05 are shown in bold font.

Model 1 = impact of race, adjusting for age and sex

Model 2 = impact of race, educational attainment, and household income, adjusting for age and sex

Model 3= race, educational attainment, and household income, adjusting for age and sex; also including additional covariates (smoking history, occupational exposures on longest held job, body mass index, and co-morbidities–see Methods)

Model 4 = age, sex, race, educational attainment, household income, additional covariates (smoking history, occupational exposures on longest held job, body mass index, and co-morbidities), and COPD severity (COPD Severity Score and BODE Score)

Joint impact of educational attainment and annual household income

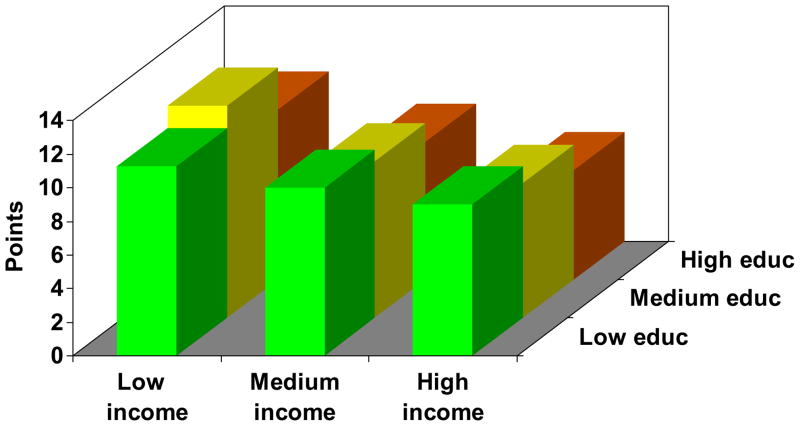

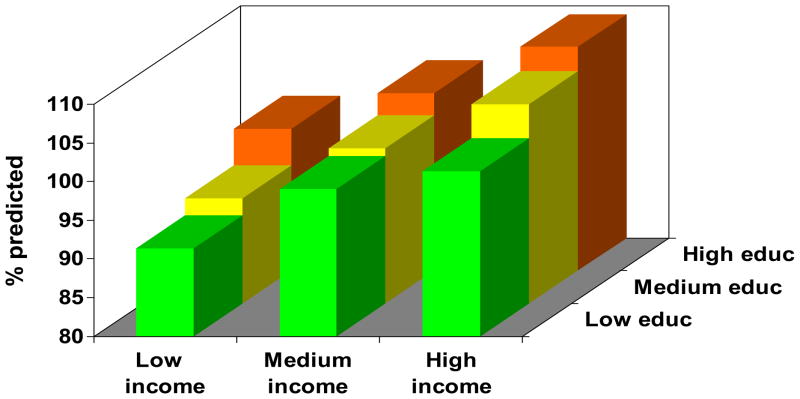

Figure 1 demonstrates a clear gradient between annual household income and each outcome measure for all levels of educational attainment, in which progressively lower income categories are associated with increasingly poor health status. Moreover, there was a clear gradient between educational attainment and each outcome measure, in which lower education categories were related to poorer health status. The education gradient was attenuated in the low income category for some outcomes (COPD severity score and distance walked in six minutes), although it had a clear impact in the medium and high income categories. In all cases, the p value for the overall joint effect of income and education was <0.0001.

Figure 1.

Joint impact of educational attainment and household income on health status in COPD. The figure depicts each education-income category, controlling for age, sex, and race. Results were derived from multivariable linear regression analysis. Low education = high school or less, medium education = some college, high education = college graduate or higher. Low income (<$20,000), medium income ($20–80,000), and high income (>$80,000). One outcome measure was selected from each category for illustrative purposes.

Figure 1a. COPD severity.

Figure 1b. FEV1%

Figure 1c. Distance walked in six minutes (Six Minute Walk Test)

Figure 1d. Acute COPD exacerbations.

DISCUSSION

Lower SES was consistently and strongly linked with poorer COPD outcomes across all measured domains among subjects who had broad access to health care. In contrast, black race was associated with greater disease severity and a higher risk of acute exacerbations, but this was entirely explained by differences in SES and other covariates (comorbidities, smoking history, body mass index, and occupational exposures). Although there was less pulmonary function impairment among black subjects (on the basis of FEV1), this subgroup manifested poorer exercise performance and lower extremity function relative to white, non-Hispanic subjects. This was attenuated, but not eliminated, by controlling for SES and potential cofactors. Other race-ethnicity groups had no consistent association with any of the COPD health outcomes studied.

The effects SES and race-ethnicity on health outcomes in COPD has not been well characterized. There have been few studies that have provided conflicting results.[8–17] In particular, studies have been mixed about the effects of SES on COPD outcomes such as HRQL and mortality.[13–16] Studies also conflict about whether black race increases the risk of COPD hospitalization.[12, 17]A study of patients admitted to the ICU for acute respiratory failure showed no impact of black race on mortality.[18] Consequently, our paper adds substantively to the literature by elucidating the clear gradient between SES and a broad array of health outcomes in COPD. Moreover, educational attainment and household income have independent impacts on COPD-related outcomes.

SES may influence COPD health outcomes through a variety of pathways. Because all FLOW subjects are members of a managed care organization, overall access to health care is not a likely mechanism. There may, however, be more subtle barriers to health care that could vary by SES, such as travel distance, work schedule flexibility, availability of pharmacies in the neighborhood, or effectiveness of patient-provider communication. Moreover, lower SES could be related to a delay in COPD diagnosis, although this was not suggested by our data (there was an inverse relationship between SES and age at cohort inception). Nonetheless, it remains possible that patients with lower SES are diagnosed with COPD later in the course of their disease, which could be an explanation for the observed association between lower SES and poorer COPD health outcomes.

The longitudinal analysis suggested that COPD severity mediates the impact of lower SES on subsequent risk of COPD exacerbations. Consequently, the impact of SES on the physical or social environment could increase disease severity and result in poorer health outcomes. In particular, SES may affect the physical environment, including region of residence, exposure to traffic and other outdoor air pollution, indoor air quality and pollution, and other factors. In particular, particulate air pollution (PM10 and PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide have been linked with a greater risk of emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and death from COPD.[53–62] Indoor fine particulate pollution (PM2.5) has also been associated with greater respiratory symptoms in COPD.[63] Recent data indicate that other indoor factors, such as home temperature, may be an important determinant of respiratory health status in COPD patients.[64] Workplace exposures to dusts or other agents may also adversely affect COPD outcomes, but we controlled for occupational exposures in our analysis.[65] In future follow-up of the cohort, we plan to assess these environmental exposures.

SES may also influence the social environment, which, in turn, could affect COPD outcomes. Neighborhood problems, social support and networks, and social capital have all been proposed as potential mediators between the effects of SES and health.[66–68] Among adults with COPD, greater social support has been associated with less dyspnea and better physical functioning.[69, 70] The effects of social environment on COPD, and the extent to which it mediates SES effects on outcomes, requires further study.

Black race had no impact on COPD severity and acute exacerbation of COPD among subjects with access to the full range of health care. Conversely, black race was adversely associated with submaximal exercise performance and lower extremity function, which was not explained by SES or lung function. For a given level of COPD severity, black patients appear to suffer more functional limitation. These findings were not explained by body mass index, height, or the other cofactors considered. They were also not explained by body composition (lean mass and fat mass from bioelectric impedance), lower extremity strength (hip flexors, hip abductors, quadriceps by dynamometry), balance (functional reach test), or depression (geriatric depression scale) (data not shown). Further research is needed to understand the impact of black race of functional limitations in COPD. Our results may also have important implications for clinical trials and epidemiologic studies, because different study endpoints may be differentially influenced by race.

A significant study strength is the large cohort of COPD patients who have a broad spectrum of disease severity, ranging from mild to severe. The cohort is also diverse in terms of SES, as well as age, gender, and race-ethnicity. Recruitment from a large health plan helps to ensure generalizability to patients who are being treated for COPD in clinical practice. Our results may not pertain to undiagnosed COPD cases or persons who do not seek medical care.

Our study is also subject to several other limitations. Although the inclusion criteria required health care utilization for COPD, misclassification of COPD could have occurred. Our COPD definition required concomitant treatment with COPD medications to increase the specificity of our definition. In addition, all patients had a physician diagnosis of COPD and reported having the condition. The observed lifetime smoking prevalence was similar to that in other population-based epidemiologic studies of COPD, supporting the diagnosis of COPD rather than asthma.[71, 72] We also previously demonstrated the validity of our approach using medical record review.[24] Nonetheless, we acknowledge this potential limitation. Because the FLOW cohort comprised subjects with established COPD, we also did not evaluate the impact of race-ethnicity and SES on the incidence of COPD (as opposed to the impact on established disease).

Selection bias could have been introduced by non-participation in the study. There were some differences among subjects who did and did not participate in interviews and clinic visits, but these were modest in scope. We were highly successful in recruiting minority subjects into the study, which would attenuate selection bias. Because we cannot know the joint distribution of race-ethnicity and SES among non-respondents, however, the potential for selection bias remains. For example, if subjects with black race and lower SES were less likely to participate, our results may reflect an overly optimistic view of the relationship between black race and COPD-related health outcomes (i.e., underestimate the impact on COPD severity). Moreover, we cannot completely exclude the role of chance as a possible explanation for the observed associations with black race.

We did have a substantive subset of subjects who declined to provide household income. Moreover, we did not have an independent method of income verification, such a tax records. This is a standard study limitation for U.S.-based analyses as compared to epidemiological studies of SES in some other locations, such as certain Scandinavian countries.

In sum, SES has important effects on a broad array of health outcomes in COPD. Black race appears to negatively affect physical functional limitations, even after accounting for SES. Regardless of the mechanism, low SES is a marker for poor outcomes and could be used by clinicians or health plans to target these high risk patients for more intensive disease management to prevent adverse outcomes. Addressing risk factors such as smoking, occupational exposures, and obesity may be important for reducing the health disparities, but further research is needed to explain the residual impact of black race on poorer COPD-related outcomes after accounting for SES and other covariates. Additional research to elucidate the pathways for SES- and race-effects in COPD will be important to effectively address the growing burden of COPD-related morbidity.

What this paper adds.

What is known

Socioeconomic status (SES) has an important influence on health and longevity

Studies indicate that race-ethnicity and SES have important impacts on adult asthma outcomes

The effects of race-ethnicity and SES on health outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), however, have not been well characterized

What this paper adds

Lower SES was strongly linked with poorer COPD outcomes across all measured domains among subjects who had broad access to health care

Black race was related to greater COPD severity, but this was entirely explained by SES and other covariates

Black race was associated with poorer exercise performance and lower extremity function, even after controlling for SES

Clinicians, researchers, and public health professionals should consider race-ethnicity as an important factor in COPD

Acknowledgments

Funded by: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute / National Institutes of Health R01HL077618

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

None declared.

References

- 1.Marmot MG, Smith GD, Stansfeld S, et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 1991;337:1387–93. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erickson SE, Iribarren C, Tolstykh IV, et al. Effect of race on asthma management and outcomes in a large, integrated managed care organization. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1846–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanc PD, Yen IH, Chen H, et al. Area-level socio-economic status and health status among adults with asthma and rhinitis. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:85–94. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00061205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisner MD, Katz PP, Yelin EH, et al. Risk factors for hospitalization among adults with asthma: the influence of sociodemographic factors and asthma severity. Resp Res. 2001;2:53–60. doi: 10.1186/rr37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omachi TA, Iribarren C, Sarkar U, et al. Risk factors for death in adults with severe asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:130–6. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60200-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang DM, Polansky M. Patterns of asthma mortality in Philadelphia from 1969 to 1991. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1542–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412083312302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, et al. Surveillance for asthma--United States, 1980–1999. MMWR Morb Mort Wkly Rpt. 2002;51:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lederer DJ, Benn EK, Barr RG, et al. Racial differences in waiting list outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:450–4. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1260OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGhan R, Radcliff T, Fish R, et al. Predictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2007;132:1748–55. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howard DL, Hakeem FB, Njue C, et al. Racially disproportionate admission rates for ambulatory care sensitive conditions in North Carolina. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:362–72. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dransfield MT, Bailey WC. COPD: racial disparities in susceptibility, treatment, and outcomes. Clin Chest Med. 2006;27:463–71. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laditka JN, Laditka SB. Race, ethnicity and hospitalization for six chronic ambulatory care sensitive conditions in the USA. Ethn Health. 2006;11:247–63. doi: 10.1080/13557850600565640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Power C, Hypponen E, Smith GD. Socioeconomic position in childhood and early adult life and risk of mortality: a prospective study of the mothers of the 1958 British birth cohort. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1396–402. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prescott E, Godtfredsen N, Vestbo J, et al. Social position and mortality from respiratory diseases in males and females. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:821–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00047502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ketelaars CA, Schlosser MA, Mostert R, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1996;51:39–43. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanner RE, Renzetti AD, Jr, Stanish WM, et al. Predictors of survival in subjects with chronic airflow limitation. Am J Med. 1983;74:249–55. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90623-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prescott E, Lange P, Vestbo J. Socioeconomic status, lung function and admission to hospital for COPD: results from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:1109–14. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13e28.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afessa B, Morales IJ, Scanlon PD, et al. Prognostic factors, clinical course, and hospital outcome of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease admitted to an intensive care unit for acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1610–5. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200207000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanc PD, Eisner MD, Yelin EH, et al. Socioeconomic gradients in tiotropium use among adults with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:483–90. doi: 10.2147/copd.s3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karter AJ, Ferrara A, Liu JY, et al. Ethnic disparities in diabetic complications in an insured population. JAMA. 2002;287:2519–27. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.19.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:703–10. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Yelin EH, et al. COPD as a systemic disease: impact on physical functional limitations. Am J Med. 2008;121:789–96. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisner MD, Iribarren C, Yelin EH, et al. Pulmonary function and the risk of functional limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:1090–101. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sidney S, Sorel M, Quesenberry CP, Jr, et al. COPD and incident cardiovascular disease hospitalizations and mortality: Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program. Chest. 2005;128:2068–75. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calfee CS, Katz PP, Yelin EH, et al. The influence of perceived control of asthma on health outcomes. Chest. 2006;130:1312–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.5.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisner MD, Yelin EH, Katz PP, et al. Risk factors for work disability in severe adult asthma. Am J Med. 2006;119:884–91. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1256–76. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2101039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eisner MD, Yelin EH, Trupin L, et al. The Influence of Chronic Respiratory Conditions on Health Status and Work Disability. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1506–13. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisner MD, Trupin L, Katz PP, et al. Development and validation of a survey-based COPD severity score. Chest. 2005;127:1890–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, et al. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1005–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez FJ, Han MK, Andrei AC, et al. Longitudinal change in the BODE index predicts mortality in severe emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:491–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200709-1383OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ong KC, Lu SJ, Soh CS. Does the multidimensional grading system (BODE) correspond to differences in health status of patients with COPD? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2006;1:91–6. doi: 10.2147/copd.2006.1.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisner MD, Iribarren C, Yelin E, et al. The BODE index and COPD severity score offer complementary assessment of COPD status. 2008;177:A399. [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Thoracic Society. Standardization of spirometry--1987 update. Statement of the American Thoracic Society. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:1285–98. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.5.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1107–36. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walters JA, Wood-Baker R, Walls J, et al. Stability of the EasyOne ultrasonic spirometer for use in general practice. Respirology. 2006;11:306–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perez-Padilla R, Vazquez-Garcia JC, Marquez MN, et al. The long-term stability of portable spirometers used in a multinational study of the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Care. 2006;51:1167–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179–87. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guyatt GH, Sullivan MJ, Thompson PJ, et al. The 6-minute walk: a new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can Med Assoc J. 1985;132:919–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sciurba F, Criner GJ, Lee SM, et al. Six-minute walk distance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: reproducibility and effect of walking course layout and length. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1522–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200203-166OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, et al. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:556–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M221–31. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M85–94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blanc PD, Iribarren C, Trupin L, et al. Occupational exposures and the risk of COPD: dusty trades revisited. Thorax. 2008 doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.099390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Sidney S, et al. Body composition and functional limitation in COPD. Respir Res. 2007;8:7. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 1997. MMWR Morb Mortl Wkly Rep. 1999;48:993–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flegal KM. Epidemiologic aspects of overweight and obesity in the United States. Physiol Behav. 2005;86:599–602. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.ECRHS Investigators. Protocol for the European Community Respiratory Health Survey. London: United Medical and Dental Schools of Guy's and St. Thomas' Hospitals, Department of Public Health Medicine; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quinlan PJ, Earnest G, Eisner MD, et al. Performance of self-reported occupational exposure compared to a job exposure matrix approach in asthma and chronic rhinitis. Occup Environ Med. 2008 doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.040022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Groll DL, To T, Bombardier C, et al. The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halonen JI, Lanki T, Yli-Tuomi T, et al. Urban Air Pollution And Asthma And Copd Hospital Emergency Room Visits. Thorax. 2008 doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.091371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dominici F, Peng RD, Bell ML, et al. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. JAMA. 2006;295:1127–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moolgavkar SH. Air pollution and hospital admissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in three metropolitan areas in the United States. Inhal Toxicol. 2000;12 (Suppl 4):75–90. doi: 10.1080/089583700750019512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ostro B, Feng WY, Broadwin R, et al. The effects of components of fine particulate air pollution on mortality in california: results from CALFINE. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:13–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee IM, Tsai SS, Chang CC, et al. Air pollution and hospital admissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a tropical city: Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Inhal Toxicol. 2007;19:393–8. doi: 10.1080/08958370601174818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ko FW, Tam W, Wong TW, et al. Temporal relationship between air pollutants and hospital admissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Hong Kong. Thorax. 2007;62:780–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.076166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naess O, Nafstad P, Aamodt G, et al. Relation between concentration of air pollution and cause-specific mortality: four-year exposures to nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter pollutants in 470 neighborhoods in Oslo, Norway. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:435–43. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang Q, Chen Y, Krewski D, et al. Effect of short-term exposure to low levels of gaseous pollutants on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations. Environ Res. 2005;99:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simpson R, Williams G, Petroeschevsky A, et al. The short-term effects of air pollution on hospital admissions in four Australian cities. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2005;29:213–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peel JL, Tolbert PE, Klein M, et al. Ambient air pollution and respiratory emergency department visits. Epidemiol. 2005;16:164–74. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000152905.42113.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Osman LM, Douglas JG, Garden C, et al. Indoor air quality in homes of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:465–72. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-589OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Osman LM, Ayres JG, Garden C, et al. Home warmth and health status of COPD patients. Eur J Public Health. 2008 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckn015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blanc PD, Eisner MD, Trupin L, et al. The association between occupational factors and adverse health outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:661–7. doi: 10.1136/oem.2003.010058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yen IH, Yelin EH, Katz P, et al. Perceived neighborhood problems and quality of life, physical functioning, and depressive symptoms among adults with asthma. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:873–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Glass R. Social capital and self-rated health: a contextual analysis. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1187–93. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. Income inequality and health: pathways and mechanisms. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:215–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Graydon JE, Ross E. Influence of symptoms, lung function, mood, and social support on level of functioning of patients with COPD. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18:525–33. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Janson-Bjerklie S, Carrieri VK, Hudes M. The sensations of pulmonary dyspnea. Nurs Res. 1986;35:154–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eisner MD, Balmes J, Katz PP, et al. Lifetime environmental tobacco smoke exposure and the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Environ Health. 2005;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance--United States, 1971–2000. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]