Abstract

Because of their large size compared to small molecules, and their multi-functionality, nanoparticles (NPs) hold promise as biomedical imaging, diagnostic, and theragnostic agents. However, the key to their success hinges on a detailed understanding of their behavior after administration into the body. NP biodistribution, target binding, and clearance are a complex function of their physicochemical properties in serum, which include hydrodynamic diameter, solubility, stability, shape and flexibility, surface charge, composition, and formulation. Moreover, many materials used to construct NPs have real or potential toxicity, or may interfere with other medical tests. In this review, we discuss the design considerations that mediate NP behavior in the body and the fundamental principles that govern clinical translation. By analyzing those nanomaterials that have already received regulatory approval, most of which are actually therapeutic agents, we attempt to predict which types of NPs hold potential as diagnostic agents for biomedical imaging. Finally, using quantum dots as an example, we provide a framework for deciding whether an NP-based agent is the best choice for a particular clinical application.

Keywords: Nanotechnology, Nanomedicine, Nanoparticles, Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging, Optical Imaging, Biodistribution, Clearance

INTRODUCTION

The Definition of Nanotechnology

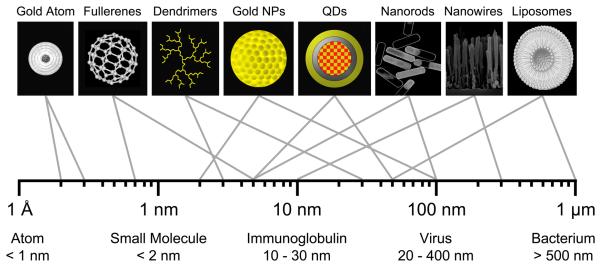

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not established its own formal definition of “nanotechnology,” and currently relies on definitions provided by the National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI).1 When determining whether a new diagnostic or therapeutic agent should be considered a “nanomaterial,” the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) within the FDA applies the following three NNI criteria: 1) Research and technology development at the atomic, molecular or macromolecular levels, in the length scale of approximately 1-100 nanometer range; 2) creating and using structures, devices and systems that have novel properties and functions because of their small and/or intermediate size; and 3) ability to control or manipulate at the atomic scale.2 Meeting these criteria is a variety of nanoparticle (NP) systems that span the range from a few nanometers to hundreds of nanometers (Figure 1). In many cases, new physical, chemical, and biological properties emerge at this nano-scale as compared to bulk materials or single atoms.1 When such NPs are applied to clinical problem solving, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) often utilizes the term “nanomedicine.”3-14

Figure 1. Relative Sizes of Nanoparticles.

Hydrodynamic diameter (HD) ranges for nano-scale materials useful for biomedical imaging (top row) and naturally-occurring materials (bottom row).

It should be emphasized, though, that from the FDA's perspective, nanomaterials are regulated like any other new diagnostic or therapeutic agent. Clinical translation of NPs must adhere to the same principles of biodistribution, clearance, and toxicology that mediate small molecules and biological agents, as well as satisfy additional concerns as described below. Unfortunately, many fundamental questions about NPs delineated in 2005 by Whitesides15 remain unanswered, including how NPs enter the body, how they are taken up by the cell, how they are distributed and eliminated in the body, and how they effect human health.

NPs and Nanotechnology in Molecular Imaging

Certain features of NPs, such as multi-functionality, multivalency, and the ability to carry large payloads have made them the subject of intense research. The term “effect size” refers to the “signal strength” of a diagnostic, therapeutic, or theragnostic agent.5,16 Unlike small molecules, which often have limited effect size, NPs can produce high signal-to-background ratios (SBR)s, can provide simultaneous contrast for multiple imaging modalities, and can carry a therapeutic payload along with contrast agents (i.e., theragnostics).17 It is precisely the large size of NPs, though, and the relationship between size and normal physiology, which makes clinical translation of NPs so difficult. In this review, we focused on the design considerations of NPs for biomedical imaging and diagnostics, but the principles apply equally to therapeutic agents and theragnostics.

In general, NPs fall into two distinct classes, those that are purely organic and those that are composed of an inorganic core (and sometimes shell) then encased with a biocompatible organic coating (Table 1). This all-important organic coating renders the NP soluble and stable in serum, determines its final hydrodynamic diameter (HD), as well as its final surface charge.

Table 1.

Classes of Nanoparticles for Multimodality Biomedical Imaging and Theragnostics.

| Class | Imaging Modality |

NP Type | Composition | Shape | HD (nm) |

Overall Charge [Core] Surface |

Pros | Cons | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic / Organic Hybrid NPs |

MRI / Multimodal Imaging |

MION, CLIO, and SPIO |

Ion oxide with polymer coating |

Globular | 5 - 200 | [None] +, − |

Conventional MRI contrast agents; EPR* |

Interference in imaging; EPR*; difficulty in Rx payload; opsonization; potential toxicity |

7,11,21 |

| Gold Nanorods & Nanoshells |

Gold-containing nanostructures |

Rod or Sphere |

2 - 100 | [None] +, − |

Size tunability; photothermal therapy; sensitivity; NIR; EPR |

67,71-74 | |||

| Optical / Multimodal Imaging |

QDs | Semiconductor core/shell arrays |

Globular | 5 - 50 | [None] +, −, +/- |

Broadband absorption; size tunability; photostability; photoefficiency; targetability |

UV decomposition; aggregation; RES uptake; high potential for toxicity |

8,77-82 | |

| Silica NPs | Ceramic silica photosensitizers |

Globular | 5 - 100 | [None] +, − |

Facile synthesis; solubility; photostability; size tunability; biocompatibility; targetability |

Need contrast agents; aggregation; mechanical stability |

95-97,154 | ||

| Molecular Dots | Calcium phosphate nanocolloids |

Globular | 20 - 100 | [−] +, − |

Facile synthesis; photostability; photoefficiency biodegradability; targetability |

Need contrast agents; EPR; difficulty in Dx and Rx payload |

101,102 | ||

| Multimodal Imaging |

Fullerenes | Carbon- containing hollow structures |

Sphere | 1 - 5 | [None] +, − |

Thermal strength; electrical properties; antimicrobial ability |

Poor water-solubility; aggregation; difficulty in purification, surface modification, and Dx and Rx payload; high potential for toxicity |

55,56,106,15 5 | |

| Carbon Nanotubes |

Carbon- containing tubes |

Cylinder | 3 - 100 | [None] +, − |

Size tunability; mechanical strength; electrical properties |

55,56,106,155 | |||

| Nanoshells and Nanowires |

Metallic semiconductors |

Sphere or Linear |

10 - 300 | [None] +, − |

Size tunability; electrical properties; high-throughput screening; thermal ablation |

108,109,111, 156 | |||

| Organic NPs |

Multimodal Imaging |

Biological NPs | Naturally derived polymers and lipoprotein conjugates |

Linear, Branched, Globular |

10 - 300 | [All] +, −, +/− |

Biocompatibility; flexibility; biodegradability; targetability |

Mechanical weakness; difficulty in size and degradability control |

24,85,116-119 |

| Polymer Nanospheres |

Repeatedly linear or branched units |

Linear or Branched |

1 - 1000 | [All] +, −, +/− |

Biodegradability; flexibility; size tunability; targetability |

Need contrast agents; Dx and Rx payload |

120,123-125 | ||

| Dendrimers | Repeatedly branched macromolecules |

Branched or Globular |

3 - 30 | [All] +, −, +/− |

Hydrophilicity; flexibility; size tunability; targetability; biocompatibility; renal clearance |

Limited synthesis; need contrast agents; Dx and Rx payload |

127-131 | ||

| Liposomes | Phospholipid bilayers |

Spherical | 50 - 1000 |

[All] +, −, +/− |

Conventional drug delivery vehicles; large Dx and Rx payload; EPR |

Need contrast agents; poor stability; EPR; opsonization |

24,51,116,132-136 |

Dx: Diagnostic; EPR: Enhanced permeability and retention; HD: Hydrodynamic diameter; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; NIR: Near-infrared; Rx: Therapeutic.

EPR is desired for passive targeting systems, but undesirable for active targeting systems.

DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF HUMAN PHYSIOLOGY

Key Design Parameters for In Vivo Imaging

Like any contrast agent used for biomedical imaging, NPs must be designed to have a reasonable blood half-life, minimal non-specific binding and uptake, selective binding to desired epitopes, such as cell surface receptors, effective elimination from the body (when NP components have any potential for toxicity), high SBR, and little or no toxicity.5,10,17 In general, the physiological behavior and pharmacokinetic parameters of NPs can be optimized by adjusting their HD, composition, shape, and surface characteristics such as charge and hydrophobicity, which are also key mediators of potential cytotoxicity and in vivo toxicity.18-22 The contribution of each is described below.

Routes of Administration and NP Biodistribution

Over the past decade, multifunctional NPs have been investigated for use in oral delivery, pulmonary delivery, ocular delivery, transdermal delivery, and traversing the blood-brain barrier (BBB).23 Oral delivery of proteins, peptides, genes, and vaccines is traditionally difficult due to poor permeability and stability in the gastrointestinal tract. However, by encapsulating these biological materials in a protective, ligand-targeted, site-specific NP carrier, they can be delivered to the intestine or the colon where an external stimulus, such as temperature or pH, can trigger the release of the diagnostic or therapeutic agent.24 In addition, increased surface area and decreased particle size can lead to increased muco-adhesion, which can increase gastrointestinal transit time and lead to increased bioavailability.25,26 Pulmonary delivery of nebulized NPs carrying immunosuppressants, either through inhalation or direct instillation into the trachea, has shown a greater therapeutic efficacy in preventing acute lung transplant rejection.27,28 However, the mechanisms underlying transpulmonary transport of NPs are only now being understood.29 Because of the tight blood-retinal barrier, systemic delivery of drugs to the retina is inefficient. However, direct administration of sustained-release NPs improves ocular residency and treatment efficacy.30 Similarly, transdermal delivery of membrane permeable NPs help control the release pattern and rate of delivery of drugs into skin and hair folicles.31 Finally, certain NPs appear to cross the BBB by either passive diffusion or carrier-mediated transcytosis.32 On one hand, this observation can be exploited to help solve the longstanding problem of drug delivery to the central nervous system (CNS) using receptor-specific, monoclonal antibody-conjugated NPs.33 On the other hand, it increases the potential for CNS toxicity after NP administration (see below).

For biomedical imaging, the preferred route of delivery is intravenous (IV) injection. However, the average size of capillary pores in normal tissues is only ≈ 5 nm.34,35 Thus, small molecules equilibrate rapidly between intravascular and extravascular spaces, but NPs do not. As a frame of reference, an IgG molecule, which has an HD in its long dimensions of ≈ 10 nm, can take up 24 hours to equilibrate between the blood and extracellular space, and up to 4 days to adequately clear after binding its target.36,37 These same principles mediate the intravascular/extravascular equilibration of NPs.38 And, when the organic coating is inadequate, NPs circulating in the blood will be removed rapidly by the reticuloendothelial system (RES; see below).39 Depending on the organic coating surrounding the NPs, nonspecific adsorption of plasma proteins, mostly albumin, can also increase effective HD, and thus extravasation.9,20 Only certain hydrophilic (i.e., zwitterionic) and neutral surfaces can prevent plasma protein adsoprtion.18,20,40 In summary, IV injection ensures that an NP can potentially have access to the entire body, but normal vascular physiology will restrict NP biodistribution, and significantly lengthen the time required for intravascular/extravascular equilibration.

Renal and Hepatic Clearance of NPs

Although some small molecules and salts can be excreted (i.e., eliminated) from the body through salivary glands and sweat, the majority of clearance for small molecules and NPs injected into the bloodstream is through either renal (urine) or hepatic (bile to feces) routes.

Renal filtration of the blood is mediated by the slit structure of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). The slit diaphragm is approximately 43 nm in diameter, but the physiologic pore size is significantly smaller, ≈ 5 nm in diameter.41,42 The physicochemical properties of NPs in serum, such as HD, dispersity, shape, flexibility, and surface charge will determine whether an NP can be renally filtered.20,39,43 Globular NPs with an HD < 6 nm are typically filtered and are eliminated from the body in urine, while those with an HD > 8 nm are not filtered at all.20 Flexible and linear-structured NPs show higher size thresholds compared to rigid and globular-structured NPs because of rectangular shape of GBM slits. NPs larger than the renal filtration threshold will exhibit long blood half-lives (often desired), but have only three possible fates: metabolism to clearable components (desired), excretion by the liver into bile (desired), or uptake in the RES resulting in long residence times in the body (undesired).38,44

NP metabolism is an area of investigation that is only now beginning to receive the attention it deserves. In general, though, a key feature of most NP systems is their extreme physicochemical stability.22 Thus in many cases, NP metabolism in the body is extremely slow, resulting in large “exposure times.” It should also be noted that the human body does not have cellular transporters for many elements used in NPs, such as cadmium,45 which means that such elements are essentially “stuck” in the body after intravenous injection. The long residence time in the body for certain elements comprising NPs is a paramount concern of many regulatory agencies concerned with human health and the environment (see below).

Large NPs with a long blood half-life eventually undergo some level of hepatic uptake by either Kupffer cells (macrophages located in the liver) and/or hepatocytes. Depending on their chemical composition, some NPs can be metabolized in the liver to components that will undergo excretion into bile. In rare cases, hydrophilic, intact NPs > 8 nm in HD are capable of biliary excretion into bile,18 although the efficiency of elimination is much lower than for renal filtration and the chemical rules mediating the process are not understood fully.

Reticuloendothelial System (RES) and Immune-Mediated Metabolism/Elimination

In general, large NPs (> 8 nm in HD) suffer from the problem of inevitable uptake by the RES, composed of phagocytic cells, primarily monocytes and macrophages, located in the reticular connective tissue of the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.39,43 In addition to size, surface charge plays a key role in RES uptake because the filtration barrier is covered with a layer of polyanionic glycoproteins, which repel most large anions.39 Surface charge and hydrophobicity promote adsorption or opsonization by serum proteins present in the blood, which bind to foreign particles, such as some NPs, and increase recognition by phagocytic cells.39 Serum protein binding also results in an effective increase in HD and can preclude renal clearance of NPs even if HD would otherwise be small enough to permit it.20 Depending on the chemical composition of the NPs, immune-mediated clearance can be a rapid or slow process.46 In general, surface modification of NPs using biologically inert, hydrophilic and neutral polymers such as poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) will slow the rate of clearance from the blood and retention in the RES.12

Tumor-Targeting Strategies

There are essentially two ways to target an NP to malignant cells: active targeting using tumor-specific ligands and clearable NPs, and passive targeting that relies on enhanced permeability and retention (EPR).47,48 We would argue that the former is difficult, but effective, and the latter is easy but essentially worthless.

Active targeting requires creating an NP that has biodistribution to the extracellular space of every tissue (both normal and tumor) and organ in the body, high affinity binding to the malignant cell, significant clearance from non-tumor tissue, and elimination from the body of that fraction of NP that doesn't bind to malignant cells. Based on what is presently known about NPs, ultra-small agents with rapid renal clearance meet these criteria,40 but are difficult to construct and nullify most of the advantages of NPs (i.e., large size).

EPR exploits the fact that tumors large enough to recruit a neovasculature (typically > 1 mm diameter) also have a dysfunctional lymphatic drainage system, and will non-specifically accumulate NPs injected into the bloodstream.9 Unfortunately, the field of nanotechnology is doing itself a grave disservice, and wasting valuable grant dollars and time, by focusing on EPR over active targeting. First, EPR requires a tumor neovasculature, which doesn't appear until tumor size exceeds ≈ 1 mm in diameter. This precludes targeting malignant cells in micrometastases, which will grow and ultimately kill the patient. Requiring tumors to grow to a size where angiogenesis has occurred, but before NP diagnosis or therapy is effective, is nonsensical. Second, we already have a large body of clinical data from nano-sized chemotherapeutics (see below) that prove the EPR “effect size” is minimal in vivo. In fact, the main reason liposomal formulations of chemotherapeutics were approved is because of reduced toxicity, due to altered biodistribution, and not because of improved efficacy.49 And, third, retention in tumors via EPR necessarily means poor elimination from the body (due to large HD and/or surface charge), resulting in eventual uptake by the RES, long body retention times, and a higher likelihood of NP toxicity.

Although EPR may play a role in limited clinical scenarios in which identification of a primary tumor, or large vascularized metastases, is desired, relying on it as a tumor targeting strategy simply avoids the inevitable conclusion: most NPs cannot be used for active targeting of micrometastases,50 and therefore, will play a minimal role in cancer diagnosis and therapy.

Interference with Other Biomedical Imaging Modalities

In the context of clinical translation, care must be taken to ensure that NPs do not themselves interfere with other, unrelated imaging modalities. For example, a large, dense NP that provides contrast for MRI might introduce a reflection that alters the interpretation of ultrasound.51,52 Similarly, a NP that provides optical contrast may alter tissue radiodensity, and ultimately the interpretation of computed tomography (CT).53

Potential Toxicity of NPs

Safety is the paramount concern for any diagnostic or therapeutic agent administered to the human body. However, NPs generate chemical, biological, and environmental concerns above and beyond those of conventional agents. Many NPs contain elements, such as gadolinium, cadmium, selenium, tellurium, arsenic, and lead, or their complexes, which are known to have acute or chronic toxicity in vertebrates.45 Particularly concerning are reproductive risks, immunotoxicity, and carcinogenicity, which are manifested only after long periods of time.54 Even when containing only carbon, the unique geometry of certain NPs have been shown to introduce unexpected biological toxicity.55-58 Finally, disposal of certain NPs may be problematic, since their remarkable chemical stability could lead to entrance into the water tables.22,59 Thus, even before the proposed advantages of nanotechnology are fully realized,15,60 increased public attention and concerns over short- and long-term toxicity abound.58,59,61

CLASSES OF NPs FOR BIOMEDICAL IMAGING, DIAGNOSTICS, THERAPEUTICS, and THERAGNOSTICS

The literature is replete with multi-functional metal-based, carbon-based, polymer-based, biological-based, and lipid-based NPs that have been proposed for biomedical imaging, diagnostics, and/or therapeutics. NP classes described to date, along with their key advantages and disadvantages, are listed in Table 1 and are described in detail as follows.

Metal Oxide NPs

Spherical ferromagnetic NPs consisting of an iron (Fe) core and a polymeric coating have been used in biomedical imaging, cell tracking, and monitoring of drug delivery.7,11 Iron oxide NPs, synthesized from ferrites composed of maghemite (Fe2O3) and magnetite (Fe3O4) metal ions, are often classified according to their effective size and coating: monocrystalline iron oxide nanocolloid (MION, 5-30 nm), cross-linked iron oxide (CLIO, 10-50 nm), and superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO, >50 nm). These NPs have been utilized extensively as contrast-enhancing probes for MRI.21 Iron oxide NPs are primarily cleared from the blood by the RES, and taken up by monocytes and macrophages, which limits their utility to the diagnosis of inflammatory and degenerative disorders associated with high macrophage activity,62 or the replacement of normal lymph node architecture with metastatic cells.63 In order to avoid opsonization, and to effect adequate biodistribution and clearance for the desired clinical indication, the physicochemical properties of these NPs require optimization.64

Gold-Containing Nanostructures

Unique NP geometries created from gold include nanorods (a nano-object with two similar external dimensions in the nano-scale and the third dimension significantly larger than the other two external dimensions), nanofibers (flexible nanorods), nanoshells (hollow NPs), and nanocages (porous wall-covered nanoshell structures).65 Gold-containing nanostructures have been explored for various biomedical applications such as drug delivery,66 imaging,67 tumor therapy,66,68 radiation sensitization,69 and sentinel lymph node mapping.70 By adjusting the core and shell thickness, gold-containing NPs offer significant flexibility in tuning the wavelengths of optical absorption and scatter, from the visible to the near-infrared (NIR; 700 to 900 nm).71-73 They also provide the ability to permit noninvasive photothermal ablation of tumors using ultrasound and microwaves, in cases where surgery would be difficult.67,74 However, care must be taken to minimize damage to surrounding normal tissue, and because of their unique geometry, penetration into skin and other organs can cause dermatitis and irritation.75 In addition, accumulation of gold salts in the body may cause other toxicity.76

Quantum Dots (QDs)

Fluorescent semiconductor nanocrystals, or QDs, contain an inorganic core, and sometimes shell, and an organic, biocompatible coating. Final HDs range from 5 to 50 nm. QDs have been used extensively in in vivo imaging as a replacement for small molecule organic fluorophores, and have been used to track biochemical processes and cancer metastases in living animals.8,77,78 Compared to conventional small molecule organic fluorophores, QDs often exhibit higher photostability, extinction coefficient, and quantum yield, and can also provide broadband absorption, narrow and tunable emission spectra, and multivalent ligand conjugation.8,79,80 Many QD chemical compositions have been shown to reach NIR emission, including InAs/ZnS,18 InAsxP1-x/InP/ZnSe,81 CdTe/CdSe,79 and Cu-In-Se.82 Because of their appropriate size (10-30 nm) and fluorescence, NIR QDs have extensively been used for sentinel lymph node mapping.79,81,83-92 After surface functionalization using small molecules, peptides, proteins, or antibodies, NIR QDs are capable of detecting targets of interest in living animals.10,77,93 Because of the need for at least one potentially toxic element to reach NIR wavelengths (e.g., In, As, Cd, or Te), and their extreme in vivo stability if not cleared adequately,94 clinical translation of NIR QDs remains stalled (discussed below).

Silica NPs

Silica is a popular component for developing biodegradable and biocompatible core-shell hybrid structured NPs because of its chemical and biological inertness and thermal stability.95-97 The crystallization and condensation reactions can be performed in aqueous systems at room temperature, which makes these NPs compatible with various heat-sensitive biomolecules that need to be incorporated into them. The charged surface permits silica colloids to be stable at high concentrations, and further modification of the surface can be accomplished using siloxane-based cross-linkers. In addition, the mesoporous silica structures permit reactants to perfuse through the shell and enter/leave the core based on their high surface area and tunable pore sizes.98 Gold, silver, platinum, and many other metals can be used to compose silica-based nanoshells for use as biosensors, biomarkers, and other biomedical detectors.99 For example, fluorophore-encapsulated silica NPs are being used as optical imaging agents with high fluorescence emission intensity, excellent photostability, and water solubility.96 Questions regarding the elimination of silica-based NPs from the body, and their potential toxicity remain unanswered.21,100

Molecular Dots

Calcium phosphate NPs are small, biocompatible, multilayer nanocomposites that are more rigid than larger liposomal structures. Calcium phosphate core-shell NPs can be synthesized via robust and reproducible methods based on biomineralization of calcium phosphate around precipitated amphiphiles. NP formation can also be controlled using ion and surfactant concentrations, pH, ionic strength, and temperature.101,102 Because of their composition, calcium phosphate NPs have a lower likelihood of toxicity compared to other types of NPs. Because they are bioresorbable and biodegradable, and diagnostic and therapeutic agents can be trapped in them during synthesis, they could potentially be used as universal carriers. Like most NPs, though, final HD is large, in the range of 20 to 100 nm, and surface modifications can be difficult.

Carbon-Based NPs

C60 buckyballs and cylindrical single-walled (SWNT) or multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNT) are hollow containers that can readily accommodate a payload of diagnostic and/or therapeutic agents. The diameter of carbon nanotubes is between 3 to 100 nm, but the length-to-diameter ratio can be as high as 2.8 × 107 to 1.103 Fullerenes and carbon nanotubes are composed solely of carbon atoms and are thus extremely hydrophobic, resulting in aggregation and nonspecific binding to plasma proteins. Efforts have been made to solubilize them in water via surface modification, including oxidation or conjugation to hydrophilic organic molecules.104 After surface modification and purification, these water-soluble cylindrical nanostructures show potential for biological research because they retain their extraordinary strength, electrical properties, and thermal conductivities. Clinical translation, however, will be slowed by concerns over their potential toxicity and difficulties in chemical modification of their surface.55,57 Carbon nanotubes, in particular, have been difficult to evaluate because of heterogeneity in size, agglomeration, and sample purity.105 Recent reports suggest that carbon nanotubes that cross the cell membrane or are retained in organs for long periods of time result in cell death and inflammation, including epithelioid granulomas and fibrotic reactions.56,106 Other reports suggest relatively low toxicity when samples are pure and used at a low dose.107

Nanowires

Metal-based semiconductor nanowires composed of silicon, carbon, and other materials are widely used as chemical and biological sensors for high-throughput detection of proteins and DNA,108,109 as well as for the potential delivery of contrast agents into living cells.110 For example, single-crystal structured silicon nanowires can be prepared as both p- and n-type materials as small as 2 to 5 nm, which perform better than planar silicon microelectronics.111 However, the diameter of nanowires significantly increases up to 10 to 300 nm when a water-soluble coating is applied for in vivo compatability.108 The needle-like shape of nanowires and carbon nanotubes, which are similar to asbestos fibers that cause mesothelioma, requires extreme caution if clinical translation is considered.112

Biological NPs

Biological NPs include nano-scale materials derived from biological components such as peptides, proteins, enzymes, antibodies, lipoproteins, viruses, and natural polymers. Naturally derived NPs frequently demonstrate high biocompatibility and biodegradability, while man-made NPs often illicit undesired bodily responses.113 Collagen and hyaluronate, the main components of extracellular matrices, are the most widely used tissue-derived natural polymers. Because they result in minimal inflammation, they can be used as biodegradable imaging probes after surface modification.114 On the other hand, NIR fluorophoreconjugated proteins and antibodies also have potential as targeting probes for the evaluation of disease progress.115 Additionally, owing to their long blood half-lives, albumin, lipoproteins, chitosan, dextran (a-1,6 polyglucose), and dextrin (a-1,4 polyglucose) have been also used as templates for carrying drugs and contrast agents after chemical or physical adsorption.24,85,116-119 Alginate and agarose are also well-known biomaterials obtained from algae polysaccharide, and are widely used in drug delivery and tissue engineering due to their biocompatibility and low toxicity. In general, biological polymers suffer from poor physical strength, difficulty in controlling size and shape of NPs, difficulty in controlling degradation, and in some cases, immunogenicity.24 Physicochemical properties can be improved by chemical cross-linking or by using chemically-modified polymers, but then the materials become non-natural chemical entities.

Polymer Nanospheres

Biodegradable and biocompatible synthetic polymers such as poly(lactic acid) (PLA), poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), poly(vinyl alcohol), poly(acrylic acid), poly(vinyl pyrrolidone), poly(ethyleneimine), poly(amino acids), poly(L-lysine), poly(glutamic acid), poly(malic acid), poly(aspartamides), poly(methyl methacrylate), poly(methylcyanoacrylate), poly(ethylcyanoacrylate), poly(isobutylcyanoacrylate), poly(isohexylcyanoacrylate), and their copolymers have been extensively used to fabricate nanospheres for the delivery and controlled-release of water-insoluble, hydrophobic drugs to sites of disease.24,120-123 By coating these polymers with other functional polymers such as PEG, poloxamines, poloxamers, or polysaccharides, “smart” polymer NPs can be produced, which release their payload only after application of a stimulus, such as pH, temperature, light, ionic strength, or chemical environment.123-125 Coating inorganic-based NPs, such as Au, QDs, silica, and carbon nanotubes, with biocompatible polymers increases stability and blood half-life, while minimizing and/or delaying RES uptake.126

Dendrimers

Dendrimers are spherical macromolecular NPs with highly branched (tree-like) internal structures. The interaction of dendrimers with the physiological environment is mainly controlled by their terminal groups. Due to their globular shape and internal cavities, dendrimers can encapsulate therapeutic agents either in their interior or on their surface. Over the last decade, poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendrimers from a 1,2-diaminoethane core and poly(propyleneimine) dendrimers have been used in a wide variety of diagnostic and therapeutic applications because they are biocompatible, have high water solubility (hydrophilicity) and flexibility, have well-defined structures, and can be easily conjugated with targeting ligands or payload.127-131 The HD of dendrimers can be controlled during chemical synthesis, and importantly, some small-sized (≤ 5 nm) dendrimers can be cleared from the blood through renal excretion.21,66,131 In general, though, dendrimers can be more expensive to produce than conventional polymers, require complex repetitive steps for synthesis, and can be difficult to scale-up for production.

Liposomes

Because of their large payload capacity and straightforward synthesis, liposomes have long been used as delivery vehicles for hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs, diagnostic agents, peptides, antibodies, hormones, and macromolecules after encapsulation by their lipid membranes.24,51,116,132-136 Although the synthesis of phospholipid bilayers does not require organic solvents, final products typically suffer from poor mechanical stability and burst leakage.39,43 By introducing inert, biodegradable coatings such as PEG, lipid membranes can be stabilized and further functionalized with various targeting/therapeutic moieties, including peptides, oligonucleotides, and proteins.24,116 However, every chemical addition to the original liposome increases HD even further, and increases the likelihood of eventual RES uptake.

FUNDAMENTALS OF CLINICAL TRANSLATION

The Regulation of Nanomaterial-Based Products

Due to ongoing safety concerns with the use of nanomaterials, the National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI) launched the Nanotechnology Environmental and Health Implications Working Group (NEHIWG) to manage the potential risks associated with nanotechnology.137 In order to help efficiently regulate potential nanotechnology research, the NEHIWG prepared the report “NNI-Strategy for nanotechnology related environmental, health and safety research” in 2008.138 The strategy identified five priority areas for Environmental Health and Safety (EHS) research and for coordination of interested agencies:139

Instrumentation, metrology and analytical methods: National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST)

Nanomaterials and human health: National Institutes of Health (NIH)

Nanomaterials and the environment: Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Human and environmental exposure assessment: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)

Risk management methods: FDA and EPA

To regulate nano-related materials, products, and processes, the FDA, EPA, NIOSH, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) have summarized EHS implications, risks and possible needs for regulations.140 Among the federally funded institutions, the FDA is authorized to regulate a wide range of products, such as drugs and devices for humans and animals, and biological products for humans under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) and the Public Health Service Act (PHS Act).

The key point to understand is that the clinical translation of NPs requires a complete understanding of the relationship between the human body and particle size, composition, formulation, supramolecular structure, chemical reactivity, and biomechanical strength and stability, as detailed in Table 2. It is also important to recognize that the FDA performs their regulatory role on a “product-by-product” basis, and that their approach to a particular product depends on the type of approval required: 1) Products subjected to pre-market approval (pharmaceuticals, high-risk medical devices, food additives, colors, and biological products), 2) products subjected to post-market surveillance (such as foods, cosmetics, radiation-emitting electronic products, and materials such as food additives and food packaging), and 3) a third mixed category of products subject to pre-market “acceptance”. In virtually all cases, NPs fall under category 1.141

Table 2.

| Category | Issue | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesis and Physicochemical Characterization |

Structure, morphology, and formulation |

Solubility, size and size distribution, morphology, structural arrangement, spatial distribution, density, geometric features, composition (organic vs. inorganic), shape (nanoemulsions, nanocrystal colloid dispersions, or liposomes), surface charge, and drug combination (drug-device, drug-biologic, drug-device-biologic) |

| Stability | Short- and long-term stability in various environments such as in serum, under different pH, temperature, and salt concentrations | |

| cGMP synthesis | Residual solvents, processing variables, impurities, and excipients | |

| Scale-up process | Critical steps in the scale-up and manufacturing process for NP products | |

| Tools | Standard characterization tools of NP properties such as NMR, MS, DLS, SEC, CE, SEM, TEM, AFM, DSC, and XRD | |

| Safety and Toxicity |

Size-specific effects on activity |

1) Will NPs gain access to tissues and cells that normally would be bypassed by larger particles? 2) Once NPs enter tissues, how long do they remain there? 3) How are they cleared from blood, tissues, and body? 4) If NPs enter cells, what effects do they have on cellular and tissue functions (transient and/or permanent)? 5) Do different cell types exhibit different effects? |

| Route-specificity | 1) Inhalation: local respiratory toxicity and bioavailability 2) Subcutaneous: sensitization 3) Dermal: bioavailability, follicular retention, local lymph nodes, and phototoxicity 4) IV: hemocompatibility, sterility, different tissue distribution and half-life of API (with targeted delivery and liposomes) 5) Oral: bioavailability 6) Ocular: intravitreal retention |

|

| ADME | 1) Absorption: how readily can the NP cross biological barriers (e.g., skin, cell membranes, and BBB)? 2) Distribution: how easy is it for the NP to travel to other locations, and what organs do the NPs tend to target? 3) Metabolism: does the nanomaterial get degraded into further constituents? 4) Excretion: do the particles get excreted or do they accumulate in various tissues? This ADME framework provides a structure that can be used to address the potential biological effects of nanomaterials. 5) What are the differences in the ADME profile for NPs versus larger particles of the same drug? 6) Are current methods used for measuring drug levels in blood and tissues adequate for assessing levels of NPs? 7) How accurate are mass balance studies, especially if levels of drug administered are very low; i.e. can 100% of the amount of drug administered be accounted for? 8) If NPs concentrate in a particular tissue, how will clearance be assessed accurately? 9) Can NPs be successfully labeled for ADME studies? |

|

| Blood tests | CBC, electrolytes, hemolysis, platelet aggregation, coagulation time, complement activation, and leukocyte proliferation | |

| Toxicity | 1) Developmental and reproductive toxicity 2) (Sub)chronic toxicology 3) Immunotoxicity 4) Neurotoxicity 5) Genotoxicity 6) Respiratory toxicity 7) Carcinogenicity 8) Histopathology |

|

| Environmental | Toxicity and elimination |

1) Can NPs be released into the environment following human or animal use? 2) What methodologies would identify the nature, and quantify the extent of NP release into the environment? 3) What might be the environmental impact on other species (animals, fish, plants, or microorganisms)? |

| Future Testing | Safety evaluation | 1) What is the role of new technologies to help identify potential toxicities? 2) What is the role of modeling (in predicting exposure, safety concerns, and design of personalized therapies)? |

AFM: Atomic force microscopy; API: Active pharmaceutical ingredient; BBB: Blood-brain barrier; CBC: Complete blood count; CE: Capillary electrophoresis; DLS: Dynamic light scattering; DSC: Differential scanning calorimetry; MS: Mass spectroscopy; NMR: Nuclear magnetic resonance; SEC: Size exclusion chromatography; SEM: Scanning electron microscopy; TEM: Transmission electron microscopy; XRD: X-ray diffraction.

FDA-Approved Nanomaterial-Based Diagnostic and Therapeutic Agents

There is much to learn from those nanomaterial-based agents already approved by the FDA (Table 3). The first is that regulatory approvals for nanomaterial-based agents are infrequent, averaging less than one per year over the last two decades, with no trend towards an increasing frequency. Second, each of the approved agents offered some quantifiable advantage over the non-nanomaterial that they sought to replace. Third, virtually all of the materials are organic. The only metal-based agent not administered as a microdose is composed of Fe, an element that in moderate quantities is required for red blood cell production and therefore acceptable if not eliminated (excreted) completely from the body. Finally, given the costs associated with regulatory approval, all but one of the agents are therapeutics, where market sizes are larger and repeated dosing guarantees an extended cash flow.

Table 3.

Currently FDA-Approved Diagnostic and Therapeutic Agents Containing Nanomaterials.158

| Year of Approval |

Product Name |

Description and Advantages | HD (nm) | Form | Route | Dx/Rx | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990/ 1995 |

Sandimmune/ Neoral |

Microemulsion-forming oral capsule including cyclosporine (cyclic polypeptide immunosuppressant agent). Prolonged survival in allogeneic transplants |

50-100 | Capsule Solution |

Oral | Rx | Novartis |

| 1994 | Oncaspar | Polymer-protein conjugate (PEGylated asparaginase); PEG-L-asparaginase conjugate for sustained release of drug to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

10-20 | Suspension | IV | Rx | Enzon |

| 1995 | Caelyx/Doxil | Doxorubicin (chemotherapeutic) encapsulated in liposomes (DSPC:PEG-DSPE:Chol) sterically stabilized by PEG. Controlled release over 60 days |

70-100 | Liposome | IV | Rx | Ortho Biotech |

| 1996 | DaunoXome/ Myocet |

Daunorubicin (chemotherapeutic) encapsulated in a closed lipid sphere (DSPC:Chol) for advanced Kaposi's sarcoma associated with HIV |

70-100 | Liposome | IV | Rx | Diatos |

| 1996 | Feridex* | Dextran-coated ultra-small iron oxide nanoparticles (ferumoxides) for MRI. Diagnosis of lymph node metastases and liver lesions |

50-250 | Suspension | IV | Dx | Amag Pharms |

| 1999 | DepoCyt | Cytarabine-encapsulated multivesicular liposomal suspension (DOPC:Chol:DPPG) | >1000 | Liposome | IV | Rx | Pacira Pharms |

| 2000 | Mylotarg | Chemo-immunoconjugate (GemtuzumAb Ozogamicin); Anti-CD33 antibody conjugated to calicheamicin for treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia |

10-20 | Suspension | IV | Rx | Wyeth Pharms |

| 2000 | Rapamune | Nanocrystallized rapamycin (immunosuppressant) in a tablet. Enhanced dissolution rate and bioavailability |

10-20 | Tablet | Oral | Rx | Wyeth Pharms |

| 2000 | Visudyne | Liposomal suspension encapsulating the drug verteporfin for photodynamic therapy (ophthalmic preparation for macular degeneration) |

100-200 | Suspension | IV | Rx | QLT |

| 2002 | Neulasta | PEGylated filgrastim; PEG-granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) for prolonged release for prevention of chemotherapy-associated neutropenia |

10-20 | Suspension | IV | Rx | Amgen |

| 2002 | Zevalin | Radio-immunoconjugate (tositumomAb and 111I/90Y); Anti-CD20 conjugated to indium-111 (dosing) or yttrium-90 (treatment) for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas |

10-20 | Suspension | IV | Rx | Spectrum Pharms |

| 2003 | Bexxar | Radio-immunoconjugate (tositumomAb and 131I); Anti-CD20 conjugated to iodine-131 (dosing/treatment) for relapsed, follicular, or transformed non-Hodgkin's lymphomas |

10-20 | Suspension | IV | Rx | Smithkline Beecham |

| 2003 | Emend | Nanocrystallized anti-emetic in an oral capsule. Enhanced dissolution rate and bioavailability |

< 1000 | Capsule | Oral | Rx | Merck |

| 2003 | Rexin-G | Pathotropic retroviral vector carrying a cytocidal gene construct. Orphan drug approval for treatment of pancreatic cancer, osteosarcoma, and soft tissue sarcoma |

100 | Suspension | IV | Rx | Epeius Biotechnology |

| 2005 | Abraxane | Paclitaxel (chemotherapeutic)-bound albumin particles. Enhanced dose tolerance and effect. Elimination of solvent-associated toxicity |

100-130 | Suspension | IV | Rx | Abraxis Bioscience |

Chol: Cholesterol; DOPC: Dioleoyl phosphatidylcholine; DPPG: Dipalmitoyl phosphatidylglycerol; DSPC: Distearoyl phosphatidylcholine; DSPE: Distearoyl phosphatidylethanolamine; Dx: Diagnostic agent; HD: Hydrodynamic diameter; IV: Intravenous; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; PEG: Poly(ethylene glycol); Pharms: Pharmaceuticals; Rx: Therapeutic agent

Discontinued.

Even though approved, none of these NPs is ideal. Lipid-based carriers pose several challenges, such as instability of the carrier, initial burst drug release, and rapid blood clearance by the RES, mostly liver and spleen, in a short period of time.24,123,142 To improve the stability and prevent opsonization by the liver, the surface of liposomes have been coated with hydrophilic and inert polymers, mostly PEG. Caelyx/Doxil and DaunoXome/Myocet, for example, are PEGylated liposome formulation to deliver doxorubicin showing enhanced circulation times and EPR effect for sustained drug release to the target. Overall, the HD of currently approved agents is extremely large, and precludes elimination through renal filtration. Feridex, for example, an FDA-approved diagnostic agent composed of ion oxide NPs (SPIO), has a diameter of 15 nm by TEM and a final HD of ≈ 50 nm due to the organic coating required for blood solubility and biocompatibility.

An added complexity when trying to translate new chemical entities to the clinic is that the FDA classifies certain combinations of conventional drugs as NPs. Bexxar (mAb-I-131), Mylotarg (mAb-chemotherapeutic), Zevalin (mAb-I-111), and even the small molecule Gd-DTPA all meet the FDA's definition of NPs because they are composed of two different components that together create a new functionality. The same is true for coating a conventional therapeutic with an inert polymer, such as PEG. Classification as an NP can become quite costly if it triggers additional pre-clinical testing that wasn't required for the individual components themselves.

NP Structural Considerations for Clinical Translation

Although the unusually small size of NPs renders their in vivo behavior unique, it is this same small size that can make them potentially dangerous to human health. NPs are not only able to evade detection by the body's immune system, but under rare circumstances have the ability to cross the BBB.32,143 The most common route of NP administration is intravenous. Once in the bloodstream, foreign substances, such as NPs, are often recognized by phagocytes of the RES. However, some NPs <100 nm in HD are not efficiently absorbed by phagocytes, thus can move freely throughout the body.143 The surface reactivity of such NPs can also cause chemical damage to surrounding tissues. When inhaled, micron-sized particles deposit in the central airways, however inhaled NPs deposit in the lung periphery causing much greater inflammation.112 Finally, just possessing nano-scale dimensions may, in and of itself, be toxic. Needle-shaped carbon nanotubes, nanowires, and nanofibers, for example, resemble the geometry of crocidolite asbestos, which can cause fibrotic lung disease and rare tumors, such as mesothelioma.112,144

Thus, a comprehensive analysis of any new nanomaterial to be administered to the human body must be undertaken in order to avoid unintended side effects. Biodistribution and clearance profiles are of paramount importance for such side effects.143 In particular, non-biodegradable NPs that accumulate in certain organs, mostly in the RES, can cause potential harm including immune-mediated toxicity, teratogenicity and carcinogenicity. The key considerations for NP interaction with the human body are provided in Table 2.

Government-Sponsored Resources Available to Assist with NP Clinical Translation

Given the complexities associated with clinical translation of NPs, investigators are fortunate to have a variety of government-sponsored resources available to them.

FDA

The FDA is a member of the Nano-scale Science and Engineering Technology (NSET) subcommittee of the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) Committee on Technology, and co-chairs with NIOSH the NSET Working Group on Nanomaterials Environmental and Health Implications (NEHI) to define new test methods to assess the safety of these products.145 The FDA also assists with the evaluation of nanomaterial toxicity studies supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and the National Toxicology Program (NTP).146 Presently, there are no testing requirements specific to nanotechnology products; however, CDER/FDA consider that existing regulatory requirements may be adequate for most nanotechnology products that they currently regulate.147 If research identifies toxicological risks that are unique to certain nanomaterials, additional testing requirements may become necessary.145

National Cancer Institute (NCI)

In 2004, the NCI initiated the Alliance for Nanotechnology in Cancer to develop and translate cancer-related nanotechnology research into clinical practice.148 To guide the implementation of the NCI Alliance, a Cancer Nanotechnology Plan (CNP) has been developed by establishing four major programs:

Centers of Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence to design and test nanomaterials and nanodevices and translate their use into clinical research.

Multidisciplinary Research Training and Team Development to create incentives to integrate nanotechnology into the mainstream of basic and applied cancer research.

Nanotechnology Platforms for Cancer Research to focus on translational research in the following 6 major challenge areas where nanotechnology can have the greatest impact: molecular imaging and early detection; in vivo nanotechnology imaging systems; reporters of efficacy; multifunctional therapeutics; prevention and control; and research enablers.

Nanotechnology Characterization Laboratory (NCL)149 to perform and standardize the preclinical characterization (pharmacology, toxicology and efficacy testing) of nanodevices (in conjunction with the FDA) to allow accelerated regulatory review and translation of basic research into the clinical domain. The NCL is also conducting material characterization and toxicology assessment for the development of cancer therapeutic drugs, and will provide the eventual drug sponsor with data to understand the toxicological risk which could be included as part of a New Drug Application (NDA) to the FDA.

National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI)

NNI reports to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), and informs the President and Congress through the OSTP regarding the investment in nanotechnology to (a) keep the U.S. at the forefront of this important and emerging industry, and (b) reduce duplication of efforts across the many U.S. Agencies.150 The NNI identified areas of health-related research that are ongoing in the U.S. government, and recommends areas where additional resources should be invested (National Nanotechnology Initiative, 2006).138 Identification of the potential toxicological hazards of nanomaterials within the U.S. government is being funded within, and through, the following agencies:

NTP-funded toxicological studies. Examples include: (a) inhalation toxicology of carbon nanotubes (conducted through an interagency agency agreement (IAG) with NIOSH), (b) fullerene toxicity (conducted through the NTP contract mechanism), (c) topical penetration and phototoxicity of TiO2 and ZnO (conducted through an IAG with the National Center for Toxicological Research (NCTR)/FDA), and (d) NCL/NCI (characterization and toxicity of cancer therapeutics; through an IAG with NTP regarding in vitro toxicity methods).

National Science Foundation (NSF) grant program

NIH extramural grant program

Environmental Protection Agency grants program (STAR)

National Toxicology Program (NTP)

Initial parameters of greatest concern to the NTP are size, shape, surface chemistry, and composition.146 Ongoing research activities are focusing initially on 4 classes of nano-scale materials: 1) metal oxides; 2) fluorescent crystalline semiconductors (QDs); 3) fullerenes; and 4) carbon nanotubes.146 NTP-published studies on the inhalation of nanomaterials suggest that particle size and distribution can impact toxicity equally, if not more so, than chemical composition.146 Surface properties can be changed by coating NPs with different materials such as PEG or zwitterionic organic materials, but such a chemical modification also influences the size of the particle.20 The interaction of surface area and particle composition in eliciting biological responses adds an extra dimension of complexity in evaluating potential adverse events that may result from exposure to nanomaterials. These engineered NPs actually distribute in the body in unpredictable ways.147

The FDA is taking significant steps to address the safety of nanomaterials as a function of their size, surface chemistry, surface physics, route of administration, and ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination).150,151 The FDA is also concerned that the current assays and tests that the agency requires sponsors to conduct in support of product safety are adequate to detect adverse biological and toxicological events. Because of these issues, the FDA is in the process of submitting the following Scientific Issues Nomination to the NTP: 1) examine the role of nano-scale size and surface coating on the fate (ADME) of nanomaterials in a rodent animal model; 2) examine the ability of nanomaterials to pass through the BBB and enter the CNS; 3) examine a select set of required test to determine their ability to detect adverse biological or toxicological effects when challenged with nanomaterials; and 4) utilize colloidal gold and silver NPs as test agent nanomaterials.150

CHALLENGES AND PERSPECTIVE

The fundamental question that one must answer before exploring any NP-based idea is whether the “nano-scale” is actually needed to solve the clinical problem at hand. Given their relatively large size, high retention in the body, and potential toxicity, many classes of NPs introduce more complexity than they may be worth. In addition, intellectual property constraints surrounding certain NPs (discussed below for QDs) often preclude efficient clinical translation.

Take, for example, a NP containing the atom gold. Gold is a potent immunotoxin, which has been used for almost a century in small amounts to treat rheumatoid arthritis. It is concerning, therefore, that gold-based nanoparticles could decompose and release gold atoms in an immunotoxic form. Moreover, gold has a linear attenuation coefficient that is 250-times higher than soft tissue. Thus, even a small fraction of gold deposited in normal organs could alter radiodensity and render CT uninterpretable. If the clinical benefits provided by gold-based NPs outweigh these clinical harms, then gold-based NPs might be viable for clinical translation. However, if there were a technology that accomplishes the same result without employing NPs, then it would be difficult to justify clinical translation.

Design Considerations of NPs Destined for Clinical Translation

The translation of many NPs into the clinic is presently being stymied by the (reasonable) mandate of the FDA that metal-containing NPs not be retained in the body. The longer a NP is retained in the body, the larger the area under the concentration-time curve, and the higher the likelihood of potential toxicity. This was one of the primary motivators for our group to develop ultra-small QDs that are cleared rapidly by renal filtration and eliminated in urine, and to develop organic surface coatings that minimize non-specific uptake and retention of NPs after intravenous injection.20,40 In the context of the current regulatory framework, and based on what is now known about how NPs interact with the human body, we propose three simple criteria to help guide clinical translation of NPs (Table 4). We would argue that an ideal NP, with a high likelihood of clinical translation, would meet all three criteria, whereas NPs meeting only one or two criteria might eventually encounter prohibitive regulatory hurdles. Of note, the third criterion concerning complete elimination from the body through renal clearance is not satisfied by some currently FDA-approved agents such as iron oxide NPs, liposomes, etc., since their components are relatively non-toxic. However, one must wonder whether the performance of these NPs (i.e., lower background) could be improved by engineering them for efficient renal clearance.

Table 4.

| Criterion | Consideration |

|---|---|

| Formulation | Composed of completely non-toxic materials and/or biodegradability to clearable (renal or hepatic) components |

| and | |

| Surface Charge | Zwitterionic or neutral organic surface coatings to minimize penetration of cellular membranes, non-specific tissue/organ uptake, and binding to serum proteins (unless only EPR-based uptake is desired) |

| and, preferably, | |

| Size and Shape | Hydrodynamic diameter of NPs or degradation products ≤ 5.5 nm to facilitate complete renal elimination in a short period of time |

An Objective Assessment of QDs and Their Viability for Clinical Translation

In order to summarize and synthesize the key points discussed in this review, consider the case of QDs. When first developed, there was huge excitement in the biomedical imaging community. Their broadband absorbance in the blue, high photostability and chemical stability, extraordinary quantum yields, and tunability from the UV to the IR were all touted as being revolutionary. However, after about a decade of investigation, many of these “features” of QDs are now classifiable as reality, myth, or indeterminate (Table 5).

Table 5.

| QD Property | Status | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Emission tunability from UV to IR | Reality | 160,161 |

| High photostability and photoefficiency | Reality | 160,161 |

| Improved total photon yield | Reality | 161 |

| Conjugation to targeting ligands | Reality | 162 |

| Potential toxicity to normal tissues/organs and/or reproductive system | Reality | 22,163 |

| All emission and material combinations are possible | Myth | 153,160,161,164 |

| Straightforward chemical synthesis without unusual explosive risks | Myth | 81,93,161,164,165 |

| Broadband absorption in scattering tissue | Myth | 153,159,166 |

| Outperform organic fluorophores as a function of molecular volume | Myth | 153,159 |

| Ultra-thin, biocompatible organic coatings widely available | +/− | 92,153,165 |

| Small enough hydrodynamic diameter for complete elimination from the body | +/− | 18,20 |

| High quantum yields in aqueous solvents and serum | +/− | 18,20 |

| High chemical stability (coating dependent) in aqueous solvents and serum | +/− | 18,153,159 |

Reality = validated by the literature. Myth = commonly accepted but not validated by the literature. +/− = examples and counter-examples available in the literature.

Although the tunability of emission wavelength is a major advantage over small molecule fluorophores, redder wavelengths require larger structures, which negatively affect biodistribution and clearance.18 Not all emission wavelengths are achievable with non-toxic elements. NIR wavelengths, in particular, suffer from the requirement for one or more toxic elements, and some syntheses are so dangerous that they should be attempted only by expert chemists. Although QD photostability is a nice feature, the excitation fluence rates that can actually be used in a clinical environment are orders of magnitude lower than QD limits, and in fact are so low that photobleaching of most small molecule fluorophores can be avoided.152 Broadband absorption of QDs is actually nullified by Rayleigh scattering tissue, causing the excitation profile to resemble a small molecule fluorophore.153 And, as a function of molecular volume, QDs underperform small molecules with respect to extinction coefficient and total photon yield.153

Finally, most QDs do not achieve a final HD compatible with renal filtration, their quantum yield in serum tends to be one-quarter that obtained in organic solvent, and their stability in warm serum is often variable. When even a 5.5 nm QD is compared directly to a 1 kDa small molecule NIR fluorophore (Figure 2), it becomes apparent that the optical performance of QDs comes at a steep price that may, or may not, be worth the added complexity. Nevertheless, if careful attention is paid to formulation, final HD, and surface charge, it is possible to develop QDs that are capable of targeting tumors efficiently after intravenous injection while being eliminated completely from the body through renal filtration (Figure 3).40

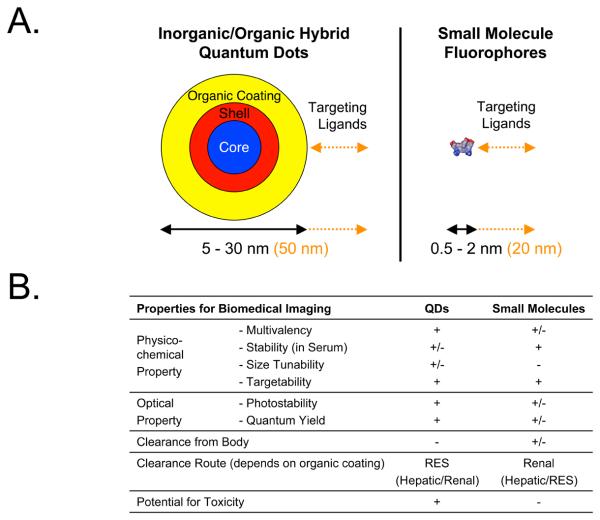

Figure 2. Physicochemical and Optical Properties of Quantum Dots (QDs) vs. Small Molecules.

A. Relative size differences between a 5.5 nm QD (left) and a typical 1 kDa heptamethine indocyanine small molecule NIR fluorophore (right). Shown below each are the ranges in hydrodynamic diameters (HDs) of non-targeted derivatives described in the literature. To the right of each (in orange) are shown the contribution of various targeting ligands, described in the literature, to final HD.

B. Summary comparison of key physicochemical and optical properties of inorganic/organic hybrid QDs vs. organic small molecule fluorophores. RES = reticuloendothelial system.

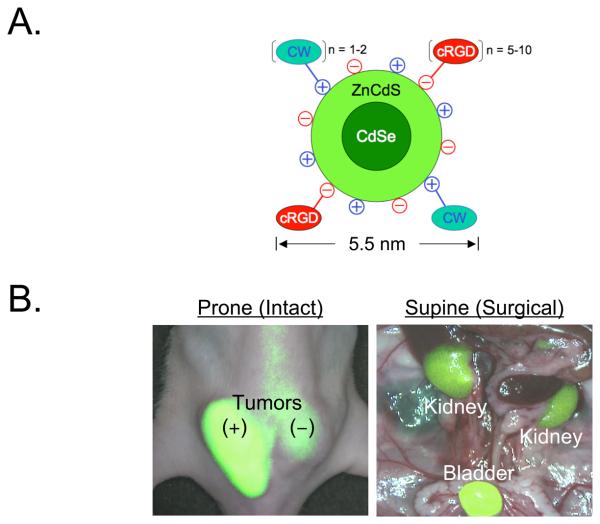

Figure 3. Ultrasmall Zwitterionic Nanoparticles and Their Rapid Renal Clearance after Effective Tumor Targeting40.

A. Chemical composition of quantum dot QD-CW-cRGD (CW800-conjugated CdSe(CdZnS) QDs with cyclic RGDyK peptide targeting ligands).

B. 10 pmol/g of QD-CW-cRGD was injected into tumor-bearing mice and observed at 4 h post-injection. Shown are merged images of color video and NIR fluorescence (pseudo-colored in lime green) acquired using the FLARE™ imaging system.167 An αvβ3-positive M21 tumor (T+) and an αvβ3-negative M21-L tumor (T−) are indicated, as are the kidneys and bladder after surgical exposure.

So, if one already has a renally-cleared, high performing QD that permits image-guided surgery of malignant tumors, why not translate it to the clinic? The first problem is one of intellectual property. A single patent in the field precludes “freedom to practice” such an invention without permission and cooperation from a certain for-profit company. Second, in order to satisfy regulatory requirements of complete elimination from the body, the QD is necessarily small. Thus, its extinction coefficient isn't significantly different from a well-designed small molecule fluorophore, and the same (or better) imaging can be achieved using such a small molecule. Third, Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP) synthesis of the QD shown in Figure 3 would be significantly more difficult than an equivalent small molecule. And, finally, regulatory scrutiny of a metal-containing QD, and the long-term toxicology tests that would undoubtedly be required, would add significant cost to clinical translation. The alternative is a class of small molecule NIR fluorophores, the heptamethine indocyanines, whose prototype indocyanine green has an extraordinary, 50+ year safety record in humans, and a facile cGMP synthesis.

CONCLUSION

Like any new technology, nanotechnology has experienced the typical sequence of unbridled excitement, relentless criticism, and now careful introspection. Is it the answer to all, or even many problems in biomedical imaging? Absolutely not. Might it play a role in the diagnosis and/or treatment of certain human conditions and diseases? It already has. As discussed in this review, the clinical translation of many types of NPs will be impeded by fundamental limitations of human physiology (i.e., vessel pore size, renal and hepatic clearance, RES), potential toxicity, and/or interference with other medical tests. At the very least, we suggest that NPs considered for clinical translation in biomedical imaging should meet as many of the “Choi Criteria” (Table 4) as are needed for the particular application. But, prior to beginning any investigation, we urge careful thought about whether the solution can't actually be found as well, well enough, or better, using atomic-scale rather than nano-scale molecules.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Professor Moungi Bawendi from MIT for many years of fruitful collaboration in the field of quantum dots, and Drs. Ingrid Markovic and Rafel Rieves from the FDA for many helpful discussions. This study was supported by Bioengineering Research Partnership grant #R01-CA-115296 to JVF from the National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute). We thank Lorissa A. Moffitt for editing, and Eugenia Trabucchi for administrative assistance.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: All intellectual property surrounding FLARE™ imaging technology is owned by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. As inventor, Dr. Frangioni may someday receive royalties if products are ever commercialized.

REFERENCES

- 1.What is nanotechnology? National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI); http://www.nano.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Approaches to safe nanotechnology: managing the health and safety concerns associated with engineered nanomaterials. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frangioni JV. Translating in vivo diagnostics into clinical reality. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(8):909–13. doi: 10.1038/nbt0806-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frangioni JV. A new approach to drug development. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(19):2046. author reply 2046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frangioni JV. New technologies for human cancer imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(24):4012–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy JR, Weissleder R. Multifunctional magnetic nanoparticles for targeted imaging and therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60(11):1241–51. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy JR, Kelly KA, Sun EY, Weissleder R. Targeted delivery of multifunctional magnetic nanoparticles. Nanomed. 2007;2(2):153–67. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao X, Cui Y, Levenson RM, et al. In vivo cancer targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22(8):969–76. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gil PR, Parak WJ. Composite nanoparticles take aim at cancer. ACS Nano. 2008;2(11):2200–5. doi: 10.1021/nn800716j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nie S, Xing Y, Kim GJ, Simons JW. Nanotechnology applications in cancer. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2007;9:257–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.152025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weissleder R, Kelly K, Sun EY, et al. Cell-specific targeting of nanoparticles by multivalent attachment of small molecules. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(11):1418–23. doi: 10.1038/nbt1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schipper ML, Iyer G, Koh AL, et al. Particle size, surface coating, and PEGylation influence the biodistribution of quantum dots in living mice. Small. 2009;5(1):126–34. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de la Zerda A, Gambhir SS. Drug delivery: keeping tabs on nanocarriers. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2(12):745–6. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai W, Chen K, Mohamedali KA, et al. PET of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor expression. J Nucl Med. 2006;47(12):2048–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitesides GM. Nanoscience, nanotechnology, and chemistry. Small. 2005;1(2):172–9. doi: 10.1002/smll.200400130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frangioni JV. The impact of greed on academic medicine and patient care. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(5):503–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt0508-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Debbage P, Jaschke W. Molecular imaging with nanoparticles: giant roles for dwarf actors. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130(5):845–75. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0511-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi HS, Ipe BI, Misra P, et al. Tissue- and organ-selective biodistribution of NIR fluorescent quantum dots. Nano Lett. 2009;9(6):2354–9. doi: 10.1021/nl900872r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu W, Choi HS, Zimmer JP, et al. Compact cysteine-coated CdSe(ZnCdS) quantum dots for in vivo applications. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(47):14530–1. doi: 10.1021/ja073790m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi HS, Liu W, Misra P, et al. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(10):1165–70. doi: 10.1038/nbt1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longmire M, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Clearance properties of nano-sized particles and molecules as imaging agents: considerations and caveats. Nanomed. 2008;3(5):703–17. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardman R. A toxicologic review of quantum dots: toxicity depends on physicochemical and environmental factors. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(2):165–72. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain KK. Drug delivery systems - an overview. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;437:1–50. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-210-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langer R. Drug delivery and targeting. Nature. 1998;392(6679 Suppl):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin S, Ye K. Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery and gene therapy. Biotechnol Prog. 2007;23(1):32–41. doi: 10.1021/bp060348j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emerich DF, Thanos CG. Nanotechnology and medicine. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2003;3(4):655–63. doi: 10.1517/14712598.3.4.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zenati M, Duncan AJ, Burckart GJ, et al. Immunosuppression with aerosolized cyclosporine for prevention of lung rejection in a rat model. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1991;5(5):266–71. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(91)90175-j. discussion 272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taljanski W, Pierzynowski SG, Lundin PD, et al. Pulmonary delivery of intratracheally instilled and aerosolized cyclosporine A to young and adult rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25(8):917–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi HS, Ashitate Y, Lee JH, et al. The complete cycle of nanoparticle trafficking from the environment, through the body, and back to the environment. 2010 in review. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vandervoort J, Ludwig A. Ocular drug delivery: nanomedicine applications. Nanomed. 2007;2(1):11–21. doi: 10.2217/17435889.2.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cappel MJ, Kreuter J. Effect of nanoparticles on transdermal drug delivery. J Microencapsul. 1991;8(3):369–74. doi: 10.3109/02652049109069563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agarwal A, Lariya N, Saraogi G, et al. Nanoparticles as novel carrier for brain delivery: a review. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(8):917–25. doi: 10.2174/138161209787582057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huwyler J, Wu D, Pardridge WM. Brain drug delivery of small molecules using immunoliposomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(24):14164–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pappenheimer JR, Renkin EM, Borrero LM. Filtration, diffusion and molecular sieving through peripheral capillary membranes; a contribution to the pore theory of capillary permeability. Am J Physiol. 1951;167(1):13–46. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1951.167.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vink H, Duling BR. Capillary endothelial surface layer selectively reduces plasma solute distribution volume. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278(1):H285–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.1.H285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bell DR, Mullins RJ. Effects of increased venous pressure on albumin- and IgG-excluded volumes in muscle. Am J Physiol. 1982;242(6):H1044–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.6.H1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goel A, Colcher D, Baranowska-Kortylewicz J, et al. Genetically engineered tetravalent single-chain Fv of the pancarcinoma monoclonal antibody CC49: improved biodistribution and potential for therapeutic application. Cancer Res. 2000;60(24):6964–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ballou B, Lagerholm BC, Ernst LA, et al. Noninvasive imaging of quantum dots in mice. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15(1):79–86. doi: 10.1021/bc034153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Murray JC. Long-circulating and target-specific nanoparticles: theory to practice. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53(2):283–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi HS, Liu W, Liu F, et al. Design considerations for tumour-targeted nanoparticles. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5(1):42–7. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deen WM, Lazzara MJ, Myers BD. Structural determinants of glomerular permeability. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281(4):F579–96. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.4.F579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohlson M, Sorensson J, Haraldsson B. A gel-membrane model of glomerular charge and size selectivity in series. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280(3):F396–405. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.3.F396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moghimi SM, Porter CJ, Muir IS, et al. Non-phagocytic uptake of intravenously injected microspheres in rat spleen: influence of particle size and hydrophilic coating. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;177(2):861–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91869-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fitzpatrick JA, Andreko SK, Ernst LA, et al. Long-term persistence and spectral blue shifting of quantum dots in vivo. Nano Lett. 2009;9(7):2736–41. doi: 10.1021/nl901534q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klaassen CD. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. Casarett & Doull's Toxicology: The Basic Science of Poisons. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gwinn MR, Vallyathan V. Nanoparticles: health effects--pros and cons. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(12):1818–25. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maeda H, Matsumura Y. Tumoritropic and lymphotropic principles of macromolecular drugs. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 1989;6(3):193–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsumura Y, Oda T, Maeda H. General mechanism of intratumor accumulation of macromolecules: advantage of macromolecular therapeutics. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1987;14(3 Pt 2):821–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rifkin RM, Gregory SA, Mohrbacher A, Hussein MA. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, vincristine, and dexamethasone provide significant reduction in toxicity compared with doxorubicin, vincristine, and dexamethasone in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a Phase III multicenter randomized trial. Cancer. 2006;106(4):848–58. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang H, Yee D, Wang C. Quantum dots for cancer diagnosis and therapy: biological and clinical perspectives. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2008;3(1):83–91. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caruthers SD, Winter PM, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Targeted magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Methods Mol Med. 2006;124:387–400. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-010-3:387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaneda MM, Caruthers S, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Perfluorocarbon nanoemulsions for quantitative molecular imaging and targeted therapeutics. Ann Biomed Eng. 2009;37(10):1922–33. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9643-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim D, Park S, Lee JH, et al. Antibiofouling polymer-coated gold nanoparticles as a contrast agent for in vivo X-ray computed tomography imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(24):7661–5. doi: 10.1021/ja071471p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oberdorster G. Pulmonary effects of inhaled ultrafine particles. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2001;74(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s004200000185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Warheit DB, Laurence BR, Reed KL, et al. Comparative pulmonary toxicity assessment of single-wall carbon nanotubes in rats. Toxicol Sci. 2004;77(1):117–25. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kolosnjaj J, Szwarc H, Moussa F. Toxicity studies of carbon nanotubes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;620:181–204. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-76713-0_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Firme CP, 3rd, Bandaru PR. Toxicity issues in the application of carbon nanotubes to biological systems. Nanomedicine. 2010;6(2):245–56. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stern ST, McNeil SE. Nanotechnology safety concerns revisited. Toxicol Sci. 2008;101(1):4–21. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt CW. Nanotechnology-related environment, health, and safety research: examining the national strategy. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(4):A158–61. doi: 10.1289/ehp.117-a158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whitesides GM. The ‘right’ size in nanobiotechnology. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(10):1161–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gilbert N. Nanoparticle safety in doubt. Nature. 2009;460(7258):937. doi: 10.1038/460937a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]