Abstract

The scale-invariant property of the cytoplasmic membrane of biological cells is examined by applying the Minkowski–Bouligand method to digitized scanning electron microscopy images of the cell surface. The membrane is found to exhibit fractal behavior, and the derived fractal dimension gives a good description of its morphological complexity. Furthermore, we found that this fractal dimension correlates well with the specific membrane dielectric capacitance derived from the electrorotation measurements. Based on these findings, we propose a new fractal single-shell model to describe the dielectrics of mammalian cells, and compare it with the conventional single-shell model (SSM). We found that while both models fit with experimental data well, the new model is able to eliminate the discrepancy between the measured dielectric property of cells and that predicted by the SSM.

Biological tissues often exhibit scale-invariant properties, namely, the structure are self-similar across multiple physical scales. Such properties can be captured in a geometric measure: the fractal dimension. During disease process the fractal dimension is often modified, and the change has been utilized in disease diagnosis and prognosis. Linking such geometric characteristics to other biophysical properties offers insights to the mechanism and the nonlinear dynamic process that leads to the formation of the fractal structure. In this study, utilizing several cell lines we show that cell membrane is close to scale invariant, and the fractal dimension captures its morphological complexity and correlates with the specific membrane capacitance. Based on these findings, we propose a new fractal single-shell model in place of the conventional single-shell model to describe the dielectric property of cells. When applied to the dielectrophoresis and electrorotation studies, the new model simulates the experimental data well, and largely resolves a long time problem of the old model, i.e., the discrepancy between the measured and the model predicted crossover frequency. In summary, this study demonstrates that cell membrane is fractal, and a mathematical model of cell dielectrics that incorporates the consideration of the fractal geometry improves the agreement with experimental data. The results suggest that the fractal geometry may play an important role in shaping cell biophysical properties.

INTRODUCTION

The structural complexity of most objects observed in nature cannot be described by the Euclidean geometry completely, their structure are complex, irregular in shape, with rough surfaces, biological cells being good examples. The structure often possesses an invariance under changes of the scale of magnification, which can be captured well by the fractal geometry.1, 2 Fractal geometry is an extension of the conventional Euclidean geometry that allows the measures to change in a noninteger or fractional way when the unit of measurement changes. This characteristic can be described by assigning a fractional number—the fractal dimension—to the dimension of the object. Fractal analysis has proven to be a useful tool in quantifying the structure of a wide range of both idealized and naturally occurring objects, extending from pure and applied mathematics, physics and chemistry, to biology and medicine. A line of study has demonstrated that scale invariance is a common characteristic of biological systems,3, 4 ranging from tissues5 to cultured cells,6, 7, 8 nucleus9 and chromatin.10, 11 Many aspects of tissue morphology considered by pathologists, such as the shapes of cell membranes7, 8 and nuclear membranes,10, 12 and the morphology of tissues,5, 13 can be described by fractal geometry. Fractal analysis can characterize the apparently irregular and complex structures in terms of a single parameter, the fractal dimension, which in turn can be related to the overall functional, pathological, or physiological status of the tissue or cells under study. For instance, it has been shown retrospectively that the composite fractal dimension of malignant mammographic cell nuclei is less than that of benign cell nuclei, suggesting the potential in developing objective and accurate cytologic diagnostic methods of breast cancer.10, 11 To our knowledge, most fractal studies until now focus on tissue, nuclear membrane, the collective surface structural behavior of cells growing in culture,7 or the perimeter of the cell surface.8 Relatively little work has been done to characterize the fractal behavior of the cytoplasmic membrane of individual cells, or correlate it to other biophysical properties of the membrane.

Dielectrophoresis (DEP) is the movement of particles in a nonuniform ac electrical field.14, 15 Up to now the dielectric response of biological cells has most frequently been described by a single-shell model (SSM).16, 17, 18 In this model, a cell is considered to have a conductive interior (a perfect sphere or ellipsoid) enclosed by a poorly conducting, perfectly concentric, and uniform membrane shell. In the frequency range of 1 kHz–10 MHz that is typically used in DEP studies, the cellular dielectric properties are dominated by the plasma membrane capacitance and conductivity. Using the SSM, cell membrane capacitance and conductivity can be determined at individual cell level from the cellular DEP responses as a function of the frequency of the applied electrical field. It has been shown that the membrane dielectric properties of different cells are highly characteristic of, and rapidly affected by, alterations in cell physiological activities or the induction of pathologic states.19, 20, 21, 22

While the SSM has achieved great success and has been widely used in the dielectrophoresis studies of biological cells,20, 23, 24, 25, 26 there are several unsolved problems. First, although it has been shown that variation in membrane morphology is a major reason for the difference in specific membrane capacitance Cmem, and several studies have used scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to show qualitatively that cells with more surface features such as microvilli, blebs, and folds tend to have larger Cmem,21, 22, 27, 28 there has been no quantitative description of the membrane morphological complexity, nor its relationship to Cmem. Second, there is a discrepancy between the measured dielectrophoretic responses and those predicted by SSM based on dielectric parameters inferred from the electrorotation measurements. The dielectric response of biological cells in an ac electric field is described well by a complex number, the Claussius–Mossotti factor, fCM.16, 17, 18 Cell rotational movement in a rotating electric field is defined by the imaginary part of fCM, and from the measurement of such movement as a function of field frequency one can derive the real part of fCM, which describes cell responses in a linear field. In practice, the crossover frequency fcrossover [the frequency at which Re(fCM)=0, and hence the cell changes direction of motion] predicted from the electrorotation spectra using the SSM is on average higher than that directly measured. The nonrandom nature of the discrepancy suggests that the SSM may have missed some aspect of the dielectric properties of biological cells.

Studies of small blocking electrodes having rough interfaces that exhibit scale-invariant characteristics have shown that their impedance shows fractional power dependence on field frequency;29, 30 existing evidence indicates that structural complexity of biological tissues can be described by the fractal geometry; our own findings suggest that the variation in cell dielectric properties is largely determined by the differences in cell membrane morphological complexity.21, 22, 27, 28 Together, these prompt the following questions: Is the cell membrane fractal? Whether∕how does its dielectric property depend on the fractal dimension? Would a model that incorporates the fractal geometry consideration resolve the discrepancy between the predicted and the measured crossover frequency?

To answer these questions, direct characterization of the relationship between DEP measurements and membrane fractal dimension of the same cells would be ideal. However, this is technically not possible. The evaluation of cell membrane fractal geometry requires high-resolution high-magnification images such as those obtained from SEM.21, 22, 27, 28 Such imaging and DEP cannot be performed on the same cells. To overcome this limitation, we adopted the following strategy. First, using a genistein (GEN) induced cell apoptosis model, where there is significant change in cell membrane morphological complexity and in Cmem at different time points,28 we compare groups of cells measured by SEM and electrorotation at the same time points to show the correlation between fractal dimension and Cmem. Based on the results, next we propose a new fractal single-shell model (FSSM) to describe cell dielectrics and apply it to analyze the DEP data of cells. We examine how well the new model fits the data, and show that it removes the systematic bias between SSM predicted and measured fcrossover. Lastly, we compare the model derived fractal dimension with the measured Cmem to indirectly validate the agreement between the measured and the model derived fractal dimension. Cmem is used to represent the measured fractal dimension since it is possible to obtain its value of the same cells, and we have demonstrated a positive correlation between measured fractal dimension and Cmem.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Image acquisition

In this study, we used HL-60, MDA-468, and MDA-361 cells. SEM imaging was performed as previously described.21, 22, 27, 28 Briefly, harvested cells were washed first and then fixed in modified Karnovsky’s fixative (280 mOs∕kg, pH 7.5) for at least 30 min. Cell specimens were examined using a Hitachi Model S520 scanning electron microscope (Hitachi Denshi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Each specimen was first scanned to evaluate the cell size and morphological distribution. Then images of representative cells were recorded at a direct magnification of 4000× onto Polaroid films (Polaroid Corp., Medical Products, Cambridge, MA). For each cell image, a center area of 300×300 pixels (6 μm×6 μm) that had little illumination variation was chosen for fractal analysis. Only images taken at the same time under identical conditions were used for comparison.

Fractal dimension calculation

Fractal dimension of cell plasma membrane is determined from the 2D gray tone SEM image. Ideally, fractal dimension of a rough surface is derived from its 3D profiles. In biological tissues this is most often not feasible. Instead, gray tone 2D images from optical6, 7, 9, 10, 11 or electron microscopy including SEM are used.8, 31 In several studies of rough surfaces, it was found that fractal dimension derived from 2D SEM images correlated well with that derived from the contact profilometry.31, 32 The SEM images were translated into 8 bit intensity (i.e., in 256 gray levels; black=0, white=255) level pictures. We adopted the Minkowski–Bouligand definition of fractal dimension.10 Through the analysis of the dependence of the intensity variation Vf versus length scale ε in log scale, the fractal dimension DMB is determined by

| (1) |

For the images analyzed here, we calculated Vf for 70 values of ε, ranging from 1 pixel (0.02 μm) to 250 pixels (5 μm). Analysis was accomplished by the algorithms implemented in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA).

Membrane capacitance and crossover frequency measurements

Cell membrane capacitance was measured using the electrorotation method as described previously.27 Briefly, cells suspended in 8.5% sucrose 2 mg∕ml dextrose were subjected to a rotating electric field. The rotation rate of cells was measured as a function of the electric field frequency. From the rotation spectrum, the capacitance and conductance of cell membrane and interior can be derived using the SSM.27, 33 The crossover frequency (fcrossover) for individual cells was determined by visually observing the cell movement toward or away from high field regions of the electrode.

RESULTS

Cell plasma membrane morphology exhibits fractal behavior

Figure 1 shows a plot of log Vf(ε) versus log ε for the gray-scale image of a typical cell. We have consistently found good linearity in the range 10≤ε≤250 (corresponding to 0.2–5 μm size scale) in all the cells we examined, suggesting that cell surface structure is self-similar within this range. This is consistent with the line of studies that found fractal geometry suitable to describe the structural complexity of biological biomaterials ranging from tissues to cells and intracellular organelles.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 31

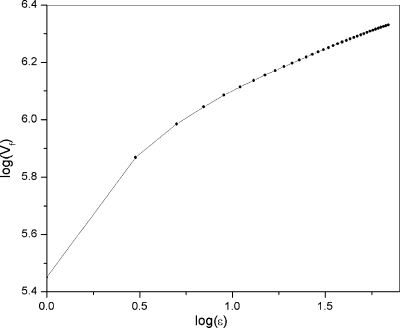

Figure 1.

The plot of log(Vf) vs log(ε) of a typical cell. Good linear dependence is observed with r2=0.998 for 2<ε<250, indicating that cell membrane surface is self-similar within this range.

For all the cells studied in this paper, we calculate DMB values using a linear fit to the log Vf(ε)−log ε plot in this range. It is known that universal self-similarity exists only in mathematical formulas or in computer algorithms, natural fractals are only self-similar in a statistical sense and usually have well-defined fractal dimensions over a limited range of scales.4 Therefore, we do not consider it surprising that good linearity was found for just part of the length scale range we studied.

Figure 1 also reveals that a concavity exists in the correlation between log(ε) and log(Vf). This was true for all of the cells we examined. Naturally occurring fractals often exhibit such concavities,6 and they may be explained by accepting that natural objects consist of fractals of different dimensions and the contributions from them change with scale.1, 6 Random processes can also generate fractal structures whose log-log plots exhibit curvature, providing an alternative mechanism to account for the concave log-log plots.34 Considering the complexity of the surface features of typical biological cells, including the microvilli, blebs, ridge-like features, folds, ruffles, and so on, likely both mechanisms play a role. Namely, the surface may contain more than one fractal, and random processes are involved in their generation.

Fractal dimension of cell membrane DMB correlates with morphological complexity

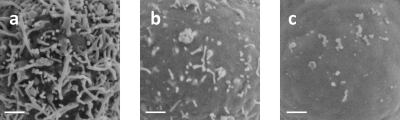

For all the three cell types studied, we found that cells with more complex, compact membrane morphological features tended to have larger DMB values and vice versa. In our previous study of HL-60 cells treated with GEN,28 we have shown that when introduced into HL-60 cell cultures at a concentration of 100 μg∕ml, GEN induces progressive loss of membrane features within hours, and that by 4 h, most cell surfaces were smooth with few villi.28 Figure 2 shows the SEM pictures of a typical cell at 0, 2, and 4 h after addition of GEN. Clearly, these three cells exhibit significant differences in membrane morphological complexity, with the cell at 0 h post-treatment showing the most complex surface and the cell at 4 h exhibiting the least membrane features. The DMB for these three cells are found to be 2.89, 2.79, and 2.59, respectively, decreasing with time and correlate well with the amount of membrane features each cell possesses. We calculated DMB for 5 cells under each condition, and the results are listed in Table 1. We conclude that the membrane fractal dimension may serve as a good objective quantifier of membrane morphological complexity.

Figure 2.

SEM pictures of cells after (a) 0 h, (b) 2 h, and (c) 4 h. GEN treatment. White bar=1 μm. A loss over time of the complexity in their membrane morphological features is evident. Their fractal dimension DMB is found to be (a) 2.89, (b) 2.79, and (c) 2.59.

Table 1.

Fractal dimension of GEN treated HL-60 cells that correlate with membrane capacitance measurements.

| Condition | DMB | Cmem (mF∕m2) a |

|---|---|---|

| (GEN, 0 h) | 2.87±0.03 | 17.6±0.9 |

| (GEN, 2 h) | 2.78±0.05 | 13.1±0.8 |

| (GEN, 4 h) | 2.66±0.05 | 9.1±0.5 |

Data in the last column are from Ref. 28.

Cell membrane fractal dimension DMB correlates with membrane capacitance

In Table 1 we also listed the membrane capacitance values of the HL-60 cells that we obtained in the previous work.28 Clearly, Cmem correlated well with the membrane fractal dimension DMB. When DMB is higher, the membrane capacitance is larger, and vice versa. This finding suggests that we may be able to give a quantitative explanation for the difference in cell membrane capacitance and cell dielectric response based on an objective measure of cell membrane structure.

NEW FSSM

Problems with the single-shell model

Presently, the SSM is commonly used to describe the dielectric responses of biological cells in an ac electric field.16, 17, 18 In this model, the Claussius–Mossotti factor fCM of the cell, which characterizes its dielectric response, is given by

| (2) |

where and are the complex permittivity of the cell and the medium, respectively, which take the form ε*=ε+σ∕jω. The real part of the Claussius–Mossotti factor describes the dielectrophoretic force on a cell, whereas the imaginary part gives the electrorotational torque on the cell. The cell interior is regarded as a smooth sphere and the membrane as a smooth, concentric shell. The cell complex permittivity is given by

| (3) |

where r is the cell radius, d is the membrane thickness, and and are the (effective) complex permittivities of cell membrane and cell interior, respectively. The surface area of a smooth sphere is 4πr2. In reality, however, a biological cell has a larger surface area than this because of surface features such as microvilli, folds, ruffles, and blebs. To accommodate this, a folding factor ϕ was introduced into the SSM23, 27, 35 so that the effective cell complex permittivity was written as

| (4) |

where εmem and σmem are the average permittivity and conductivity of the entire membrane if it were smooth, andϕ=A∕4πr2 (>1) is the so-called membrane folding factor,27 which is the ratio of the true membrane area A to the area of a cell of the same diameter with a perfectly smooth membrane.15 The specific membrane capacitance is then given by Cmem=(εmem∕d)ϕ. It has been shown that the difference in membrane dielectric properties of different cell lines mainly results from differences in the membrane morphology-dependent folding factor ϕ.27

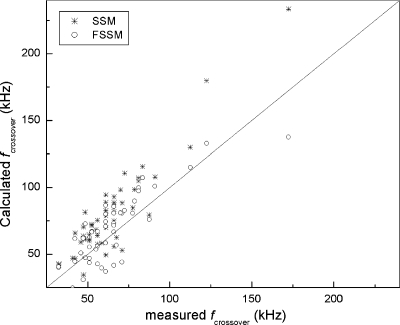

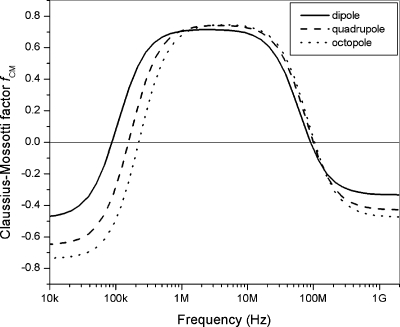

While this model has achieved great success since being introduced, it leads to several unsolved problems. Most importantly, the discrepancy between the measured DEP responses and those predicted based on the cell dielectric parameters derived from electrorotation measurements. This problem is illustrated in Fig. 3 where the DEP crossover frequency, fcrossover, the frequency at which Re(fCM)=0, predicted from the electrorotation measurement using the SSM is plotted against the measured values of fcrossover for 25 MDA-468 cells and 25 MDA-361 cells. Evidently, in most cases the predicted values are about 10–50 kHz higher than that measured by DEP (most data points are above the 45° line). The average difference (15.6±15.6 kHz) is significant with p<1×10−10 (Table 2, paired t-test). Nonlinear dielectric effects cannot account for these discrepancies. Figure 4 plots the real part of Claussius–Mossotti factor for a typical cell including contributions up to dipole, quadrupole, and octopole terms, using the formula given in Ref. 18. Clearly, higher order nonlinear terms actually work against resolving the observed discrepancies.

Figure 3.

DEP crossover frequency fcrossover derived from electrorotation measurement, using SSM or FSSM, vs that directly measured. The values predicted by the SSM are consistently higher than the measured values.

Table 2.

Crossover frequency predicted using the FSSM is closer to the measured values as compared with the predictions made using the SSM.

| fcrossover (kHz) | fcrossover,fit−fcrossover,exp (kHz) | Significance of difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured | 64.9±23.8 | ||

| SSM | 80.5±34.3 | 15.6±15.6 | p<1×10−10 |

| FSSM | 68.1±25.1 | 3.2±13.8 | n.s.(p∼0.43) |

Figure 4.

The dipole, quadrupole, and octopole contributions to Re(fCM) for a typical cell.

FSSM

With new knowledge of the fractal characteristics of the cell membrane, we propose an alternative way to take into account the complexity of cell surface features in analyzing cell dielectric responses. It is known that for small blocking electrodes having rough interfaces that exhibit scale-invariant characteristics, the impedance often shows fractional power dependence on field frequency.29, 30 Specifically, it is found that the frequency response of impedance can be described in terms of a fractal dimension Df,

| (5) |

where a=1∕(Df−1), and a=1 for a smooth surface. Studies of biological tissues where there is scale-invariant behavior in structure have also demonstrated fractal behavior in dielectric responses.36, 37 In an analogous fashion, we propose an alternative expression for the effective complex permittivity of a fractal membrane surface as

| (6) |

where α depends on the fractal dimension DMB of the cell membrane surface. Compared with the SSM, FSSM uses a parameter α to describe the contribution of cell membrane morphological complexity to its dielectrics, instead of the folding factor ϕ.

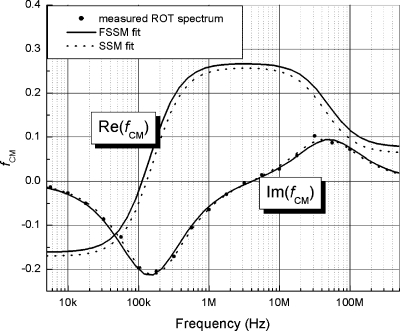

Comparison with SSM

Figure 5 shows the electrorotation spectrum of a MDA468 cell fitted using both the SSM and the FSSM, and the corresponding DEP responses derived from the fits. Both models provide good fits, and predict fairly similar DEP responses. However, close inspection reveals that the DEP crossover frequency, fcrossover, predicted by the FSSM is lower than that by the SSM. We have since applied FSSM to the analysis of several hundreds of cells and found FSSM consistently predicted a lower crossover frequency than the SSM. In Fig. 3, we included the fcrossover values predicted by the FSSM for the same 50 cells. Evidently, all data points are more randomly distributed around the 45° line. Table 2 summarizes the average fcrossover for measured data and that derived using the two models. The discrepancy between predicted and measured fcrossover is largely corrected using the FSSM model, the difference is no longer significant with p>∼0.43 (paired t-test). These results indicate that the FSSM offers a more accurate description of cell dielectric responses.

Figure 5.

The electrorotation spectrum of a typical cell, fitted using SSM and FSSM, together with the corresponding derived Re(fCM). Both models fit the data well, but the FSSM predicts lower fcrossover than SSM.

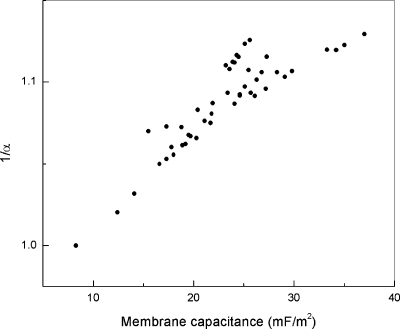

Cell membrane fractal dimension DMB and α

In the FSSM, we assume that α is a fractional number that depends on the membrane fractal dimension. It would be desirable to compare directly on the same cells, if feasible, the α values (derived from electrorotation spectra) with DMB (calculated from SEM pictures) to see if a relationship holds similar to the observations made of electrodes with fractal surfaces29, 30 [see Eq. 5]. Unfortunately, it is not possible to perform electrorotation measurements and SEM on the same cells. We instead compared α values with Cmem, which correlates positively with the fractal dimension DMB (Table 1). Figure 6 shows the plot of 1+1∕α versus the specific membrane capacitance Cmem for the same 50 cells presented in Fig. 3. A linear relationship is evident. This suggests that it is highly probably that α is inversely related to DMB. Finding the exact relationship between them requires further work.

Figure 6.

(1∕α+1) correlate well with the specific membrane capacitance.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that the cell cytoplasmic membrane morphology exhibits fractal behavior, and the fractal dimension correlates with cell membrane specific capacitance. Utilizing this knowledge, we developed a new FSSM to describe cell dielectric properties and to predict cell kinetics in dielectrophoresis manipulation. We demonstrated that it fitted well with experimental data, and resolved the disagreement between DEP and electrorotation. It is known that membrane structural complexity affects its dielectric properties.23, 27, 35 FSSM offers an alternative description of the complexity to the folding factor ϕ.

The results in Figs. 35 suggest that the predictions between FSSM and SSM are not remarkably different. The conventionally used SSM is not a bad model, it captures the bulk part properties of the cell dielectric behavior, and until now has been extensively utilized in dielectrophoretic studies.16, 17, 18 Therefore, we do not expect a huge difference between the new model and the SSM. However, we do want to emphasize that despite the success of the SSM, the fcrossover it predicts is systematically higher than the measured value (p<1×10−10 in our data). This indicates that the SSM overlooked a certain aspect of the dielectric properties of biological cells. In contrast, the difference between the measured fcrossover and that predicted by FSSM is more of a random nature, and on average not significant.

Fractal dimensions of biological cells and tissues are useful morphological descriptors in establishing links between structure and function. Cell membrane is crucial in maintaining cell homeostasis, and changes in homeostasis are known to result in alterations of membrane structure and function. For instance, cells that undergo programmed cell death exhibit reductions in membrane structural features;38 malignant cells tend to have more abundant surface structural features as compared with benign cells, which is believed to be important in enabling the malignant cells to cope with the enhanced demand of metabolites uptake, and contribute to their hyperactivity and heterogeneity.39 The work presented here demonstrated that cell membrane exhibits scale-invariant behavior and that the fractal dimension may be a good measure of the complexity of membrane features. We believe that further analysis of cell surfaces, such as a mathematical classification to identify the dynamical processes that give rise to the surface structures observed, will not only be valuable in understanding the mechanisms involved in maintaining normal cell homeostasis, but may also lead to diagnostic and prognostic markers for disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jamileh Noshari and Celine Joyce for tissue culture. We are grateful to Kenneth Dunner, Jr. and the High Resolution Microscopy Facility at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center for SEM, and Dr. Jun Yang for help in electrorotation measurements. We thank Justin Carter for careful reading of the manuscript. This work is supported by the National Institute for Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Grant No. 5RO1 DK51065-6. SEM was made possible by NIH Core, Grant No. P30-CA16672.

References

- Mandelbrot B. B., The Fractal Geometry of Nature (Freeman, New York, 1983). [Google Scholar]

- Pentland A. P., “Fractal-based description of natural scenes,” IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 6, 661 (1984). 10.1109/TPAMI.1984.4767591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross S. S., “Fractals in pathology,” J. Pathol. 182, 1 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- T. G.Smith, Jr., Lange G. D., and Marks W. B., “Fractal methods and results in cellular morphology—Dimensions, lacunarity and multifractals,” J. Neurosci. Methods 69, 123 (1996). 10.1016/S0165-0270(96)00080-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazit Y., Baish J. W., Safabakhsh N., Leunig M., Baxter L. T., and Jain R. K., “Fractal characteristics of tumor vascular architecture during tumor growth and regression,” Microcirculation (Philadelphia) 4, 395 (1997). 10.3109/10739689709146803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaut J. P., Schoevaert-Brossault D., Downs A. M., and Landini G., “Asymptotic fractals in the context of grey-scale images,” J. Microsc. 189, 57 (1998). 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1998.00284.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilela M. J., Martins M. L., and Boschetti S. R., “Fractal patterns for cells in culture,” J. Pathol. 177, 103 (1995). 10.1002/path.1711770115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keough K. M., Hyam P., Pink D. A., and Quinn B., “Cell surfaces and fractal dimensions,” J. Microsc. 163, 95 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo H. R., Lapidus A., and Lambert W. C., “Identification of early apoptosis in Feulgen-stained cultured cells in situ by computerized image analysis,” Cytometry 33, 420 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein A. J., Wu H. -S., and Gil J., “Self-affinity and lacunarity of chromatin texture in benign and malignant breast epithelial cell nuclei,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 397 (1998). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein A. J., Wu H. S., Sanchez M., and Gil J., “Fractal characterization of chromatin appearance for diagnosis in breast cytology,” J. Pathol. 185, 366 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landini G. and Rippin J. W., “An “asymptotic fractal” approach to the morphology of malignant cell nuclei,” Fractals 1, 326 (1993). 10.1142/S0218348X93000356 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson I. H. and Fazzalari N. L., “Methodological principles for fractal analysis of trabecular bone,” J. Microsc. 198, 134 (2000). 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2000.00684.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias F. J., Santamaria C., Asencor F. J., and Dominguez A., “Dielectrophoresis: Effect of nonuniform electrical fields on cell movements,” in Electrical Manipulation of Cells, edited by Lynch P. T. and Davey M. R. (Chapman and Hall, New York, 1996), pp. 71–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann U. and Neil G. A., Electromanipulation of cells (CRC, Boca Raton, FL, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Irimajiri A., Hanai T., and Inouye A., “A dielectric theory of “multi-stratified shell” model with its application to a lymphoma cell,” J. Theor. Biol. 78, 251 (1979). 10.1016/0022-5193(79)90268-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. B., Electromechanics of Particles (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Wang X. -B., and Gascoyne P. R. C., “General expression for dielectrophoretic force and electrorotational torque derived using the Maxwell stress tensor method,” J. Electrost. 39, 277 (1997). 10.1016/S0304-3886(97)00126-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Arnold W. M., and Zimmermann U., “Alterations in the electrical properties of T and B lymphocyte membranes induced by mitogenic stimulation. Activation monitored by electro-rotation of single cells,” Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1021, 191 (1990). 10.1016/0005-2736(90)90033-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascoyne P. R. C. J., Noshari B. F. F., and Pethig R., “Use of dielectrophoretic collection spectra for characterizing differences between normal and cancerous cells,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 30, 829 (1994). 10.1109/28.297896 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Wang X. B., Becker F. F., and Gascoyne P. R., “Membrane changes associated with the temperature-sensitive P85gag-mos-dependent transformation of rat kidney cells as determined by dielectrophoresis and electrorotation,” Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1282, 76 (1996). 10.1016/0005-2736(96)00047-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Huang Y., Wang X., Wang X. B., Becker F. F., and Gascoyne P. R., “Dielectric properties of human leukocyte subpopulations determined by electrorotation as a cell separation criterion,” Biophys. J. 76, 3307 (1999). 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77483-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascoyne P. R., Wang X. B., Huang Y., and Becker F. F., “Dielectrophoretic separation of cancer cells from blood,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 33, 670 (1997). 10.1109/28.585856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pethig R. and Markx G. H., “Applications of dielectrophoresis in biotechnology,” Trends Biotechnol. 15, 426 (1997). 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01096-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Huang Y., Wang X. B., Becker F. F., and Gascoyne P. R., “Differential analysis of human leukocytes by dielectrophoretic field-flow-fractionation,” Biophys. J. 78, 2680 (2000). 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76812-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Huang Y., Wang X. -B., Becker F. F., and Gascoyne P. R. C., “Cell separation on microfabricated electrodes using dielectrophoretic/gravitational field-flow fractionation,” Anal. Chem. 71, 911–918 (1999). 10.1021/ac981250p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. B., Huang Y., Gascoyne P. R., Becker F. F., Holzel R., and Pethig R., “Changes in Friend murine erythroleukaemia cell membranes during induced differentiation determined by electrorotation,” Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1193, 330 (1994). 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90170-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Becker F. F., and Gascoyne P. R., “Membrane dielectric changes indicate induced apoptosis in HL-60 cells more sensitively than surface phosphatidylserine expression or DNA fragmentation,” Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1564, 412 (2002). 10.1016/S0005-2736(02)00495-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan T. and Gray L. J., “Effect of disorder on a fractal model for the ac response of a rough interface,” Phys. Rev. B 32, 7360 (1985). 10.1103/PhysRevB.32.7360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyikos L. and Pajkossy T., “Fractal dimension and fractional power frequency-dependent impedance of blocking electrodes,” Electrochim. Acta 30, 1533 (1985). 10.1016/0013-4686(85)80016-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chappard D., Degasne I., Hure G., Legrand E., Audran M., and Basle M. F., “Image analysis measurements of roughness by texture and fractal analysis correlate with contact profilometry,” Biomaterials 24, 1399 (2003). 10.1016/S0142-9612(02)00524-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiqiang W., Skands U., and Conradsen K., “Evaluation of fracture roughness using two kinds of fractal dimension measurements,” Acta Stereol. 14, 45 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Gimsa J., Glaser R., and Fuhr G., “Theory and application of the rotation of biological cells in rotation electric fields (electrorotation),” in Physical Characterization of Biological Cells, edited by Schütt W., Klinkmann H., Lamprecht I., and Wilson T. (Verlag Gesundheit, Berlin, 1991), pp. 295–323. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger D., Biham O., and Avnir D., “Apparent fractality emerging from models of random distributions,” Phys. Rev. E 53, 3342 (1996). 10.1103/PhysRevE.53.3342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhorukov V. L., Arnold W. M., and Zimmermann U., “Hypotonically induced changes in the plasma membrane of cultured mammalian cells,” J. Membr. Biol. 132, 27 (1993). 10.1007/BF00233049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissado L. A., “A fractal interpretation of the dielectric response of animal tissues,” Phys. Med. Biol. 35, 1487 (1990). 10.1088/0031-9155/35/11/005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart F. X. and Dunfee W. R., “In vivo measurement of the low-frequency dielectric spectra of frog skeletal muscle,” Phys. Med. Biol. 38, 1099 (1993). 10.1088/0031-9155/38/8/008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie A. H., “Apoptosis (The 1992 Frank Rose memorial lecture),” Br. J. Cancer 7, 205 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follett E. A. and Goldman R. D., “The occurrence of microvilli during spreading and growth of BHK21-C13 fibroblasts,” Exp. Cell Res. 59, 124 (1970). 10.1016/0014-4827(70)90631-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]