Abstract

Myeloid elf-1-like factor (MEF) or Elf4 is an E-twenty-six (ETS)-related transcription factor with strong transcriptional activity that influences cellular senescence by affecting tumor suppressor p53. MEF downregulates p53 expression and inhibits p53-mediated cellular senescence by transcriptionally activating MDM2. However, whether p53 reciprocally opposes MEF remains unex-plored. Here, we show that MEF is modulated by p53 in human cells and mice tissues. MEF expression and promoter activity were suppressed by p53. While we found that MEF promoter does not contain p53 response elements, intriguingly, it contains E2F consensus sites. Subsequently, we determined that E2F1 specifically binds to MEF promoter and transactivates MEF. Nevertheless, E2F1 DNA binding and transactivation of MEF promoter was inhibited by p53 through the association between p53 and E2F1. Furthermore, we showed that activation of p53 in doxorubicin-induced senescent cells increased E2F1 and p53 interaction, diminished E2F1 recruitment to MEF promoter and reduced MEF expression. These observations suggest that p53 downregulates MEF by associating with and inhibiting the binding activity of E2F1, a novel transcriptional activator of MEF. Together with previous findings, our present results indicate that a negative regulatory mechanism exists between p53 and MEF.

INTRODUCTION

MEF/ELF4 is a member of the E-twenty -six (ETS) family of transcription factors, which function as transcriptional activators or repressors and regulate critical aspects of cellular differentiation, proliferation and transformation (1). MEF was originally isolated from human megakaryocytic leukemia cell line, and is known to activate the expression of a variety of cytokine genes, such as interleukin (IL)-3 and IL-8 (2,3) and antibacterial peptides, such as lysozyme and human β-defensin and the cytolytic molecule perforin (4–6). MEF expression and activity are regulated by its post-translational modification, protein–protein interaction and by transcription. MEF expression is highest at G1 phase; and at G1 to S-phase transition, MEF is phosphorylated by cyclinA–cdk2 complex, ubiquitinated by SCFskp2 and degraded by proteasome (7,8). SUMOylation of MEF inhibits its transcriptional activity (9), whereas translocation of MEF into promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear bodies induces interaction with PML and increases MEF transcriptional activator function (10,11). Sp1 was previously determined to positively influence the transcription of MEF (12). Epigenetic regulation, promoter methylation and histone deacetylation mediate MEF gene silencing (our unpublished data) (13).

Besides its function as an activator of cytokines and innate immune molecules, MEF also impacts on cell-cycle progression by promoting the transition of cells from G1 to S phase (7). The loss of MEF was shown to increase tumor suppressor p53 protein and enhance hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) quiescence in murine embryonic fibroblasts, implicating MEF in driving HSC from quiescence to G1 phase by opposing p53 function (14,15). A study previously demonstrated that MEF upregulates the transcription of MDM2, the E3 ubiquitin ligase of p53, thereby suppressing p53 protein stability that led to the inhibition of p53-dependent oncogene-induced cellular senescence (16). Considering that MEF contributes to driving cell-cycle progression and that MEF suppresses p53, which is known for promoting cell-cycle arrest and senescence, we hypothesized that p53, in turn, affects MEF expression. Here, we present evidence that p53 downregulates MEF expression. p53 overexpression or activation of endogenous p53 repressed MEF levels, whereas in the absence of p53 in human epithelial cells and mice tissues, higher MEF expression level was observed. By investigating the mechanism of this downregulation, we found that p53 inhibits the promoter-binding activity of E2F1, which we also show here as a novel transcriptional activator of MEF. Exogenous addition of E2F1 upregulated MEF expression and promoter activity; conversely, E2F1 knockdown reduced MEF transcription. Furthermore, p53 inhibited the DNA binding of E2F1 to MEF promoter by associating with E2F1, which led to the suppression of MEF levels. These findings describe the direct positive regulation of MEF by E2F1 and the suppression of MEF by p53.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies

Nutlin-3 was from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA, USA). Doxorubicin was from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). Antibody for MEF was obtained from Transgenic Inc. (Kumamoto, Japan). Mouse anti-p53 (DO-1), rabbit anti-E2F1 (C-20), mouse IgG (sc-2025), rabbit IgG (sc-2027) and γ-tubulin (sc-7396) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies used in this study were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. (West Grove, PA, USA).

Cell culture, treatment and transfection

Human colorectal cancer cell line, HCT116 p53+/+ and HCT116 p53−/− cells were kindly provided by Dr. B. Vogelstein from Johns Hopkins University. These cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/Ham’s F-12 (DMEM/F12) medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Human bronchial epithelial cells, 16HBE14o-, were donated by Dr. D. Gruenert from the California Pacific Medical Center (San Francisco, CA, USA). 16HBE14o- cells were cultured in Minimum Essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics, and grown in fibronectin-coated dishes. Lung adenocarcinoma, A549, and human embryonic kidney, HEK293, were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS and antibiotics. Human hepatoma cells, HepG2, were maintained in MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. A549, HEK293 and HepG2 cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. All cell lines were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Treatment of cells with nutlin-3 or DMSO (control) was carried out for 24 h (HCT116 cells) or 48 h (HepG2 cells). Transient transfections of plasmids were performed using Hilymax (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) following the manufacturer’s recommendation. Specifically, Hilymax diluted in Opti-MEM (Gibco) was mixed with total DNA in a ratio of 1:4 (DNA/Hilymax) and applied to subconfluent cells. Small-interfering RNA (siRNA) for p53 or E2F1 was transfected into cells using Trans-IT TKO (Mirus, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. p53 or E2F1 siRNA duplex (50 nM) complexed with Trans-IT TKO (1:4; siRNA/TKO ratio) was transfected into 70% confluent cells. GL2-luc siRNA duplex was used as control. The cells were harvested 48 h after transfection. The siRNA oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

siRNA oligonucleotide sequences

| Gene | Sense | Antisense |

|---|---|---|

| p53 siRNA | 5′-GACUCCAGUGGUAAUCUACTT-3′ | 5′-GUAGAUUACCACUGGAGUCTT-3′ |

| E2F1 siRNA | 5′-AAGUCACGCUAUGAGACCUCATT-3′ | 5′-UGAGGUCUCAUAGCGUGACUUTT-3′ |

| GL2 siRNA | 5′-CGUACGCGGAAUACUUCGATT-3′ | 5′-UCGAAGUAUUCCGCGUACGTT-3′ |

Real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA was isolated from cells and mice tissues using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbard, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) analyses for human or mouse MEF and internal controls GAPDH or 18S ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA) were carried out with SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbard, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR amplifications were performed as described previously (17). The Ct values for each gene amplification were normalized by subtracting the Ct value calculated for GAPDH or 18S rRNA. The normalized gene expression values were expressed as the relative quantity of MEF gene-specific messenger RNA (mRNA). The oligonucleotide primers used in the real-time quantitative PCR amplifications are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers used for real-time quantitative RT-PCR

| Gene | Sense | Antisense |

|---|---|---|

| Human MEF | 5′-TGGAAGGCAGTTTTTTGCTGA-3′ | 5′-GACTTCCGCGGTTGACATG-3′ |

| Human GAPDH | 5′-CGGGAAGCTTGTGATCAATGG-3′ | 5′-GGCAGTGATGGCATGGACTG-3′ |

| Human 18S rRNA | 5′-CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA-3′ | 5′-GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT-3′ |

| Mouse MEF | 5′-TCCTGGATGAGAAGCAGATCTTCA-3′ | 5′-ATGGTGCTGCCTTTGCCATC-3′ |

| Mouse 18S rRNA | 5′-GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT-3′ | 5′-CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG-3′ |

Plasmids and luciferase assay

The cloning of MEF promoter constructs (–849/+181; −384/+181; −204/+181 bp) in luciferase reporter vector, pGL3 basic vector, (pGL3b; Promega Corp. Madison, WI, USA) was described previously (12). MEF promoter constructs containing mutation/s in E2F binding sites (MT1, MT2 and MT1&2) were prepared using QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene. La Jolla, CA, USA) following the recommended protocol. The primers used for generating MEF mutant promoters are listed in Table 3. The p53 expression plasmid was cloned in pCDM8 expression vector as described in (18). The E2F1 expression plasmid (Addgene plasmid 10736) was purchased from Addgene.

Table 3.

Primers used for the generation of mutant MEF promoter constructs

| Gene | Sequence |

|---|---|

| MEF prom MT1_sense | 5′-GACCGGGCGCCCGTGGATCCTTCCACTTCTC-3′ |

| MEF prom MT1_antisense | 5′-GAGAAGTGGAAGGATCCACGGGCGCCCGGTC-3′ |

| MEF prom MT2_sense | 5′-CTTGCCATTGGCGGCACCTAGGGTGGGAGAGC-3′ |

| MEF prom MT2_antisense | 5′-GCTCTCCCACCCTAGGTGCCGCCAATGGCAAG-3′ |

For luciferase assays, HCT116 and HEK293 cells seeded onto 12-well plates were transfected with 0.2 µg of MEF-luc promoter construct, together with 20 ng of Renilla luciferase plasmid (phRG-TK; Promega), p53, E2F1 expression plasmids and/or pcDNA3.1 empty vector (control). Luciferase activity was determined using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay system (Promega) as described previously (19).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

To determine E2F1 binding to MEF promoter, nuclear extracts from HCT116 and HEK293 cells were used for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay following the protocol described previously (20). Two micrograms of anti-E2F1 antibody or normal rabbit IgG was incubated with pre-cleared chromatin. Samples were analyzed by PCR using LA Taq Polymerase (TaKaRa) according to the recommended protocol. The primers used (Table 4) recognize a fragment of the human MEF promoter, CDC6 promoter or GAPDH promoter.

Table 4.

Primers used for ChIP assay

| Gene | Sense | Antisense |

|---|---|---|

| MEF promoter | 5′-CTCGAGCCTCCAACTTCCCATTGG-3′ | 5′-CTCGAGGCTCAACTTCCACTTCTCC-3′ |

| CDC6 promoter | 5′-AAAGGCTCTGTGACTACAGCCA-3′ | 5′-GATCCTTCTCACGTCTCTCACA-3′ |

| GAPDH promoter | 5′-AAAAGCGGGGAGAAAGTAGG-3′ | 5′-CTAGCCTCCCGGGTTTCTCT-3′ |

Immunoprecipitation and western blotting

To analyze the interaction between p53 and E2F1, transfected or doxorubicin-treated HCT116 cells were lysed with nuclear extraction buffer as previously described in ref. 5. Nuclear extracts were incubated for 12 hr at 4°C with 2 μg anti-p53 or anti-E2F1 antibodies or control IgG immobilized in protein G Sepharose beads (Amersham Bioscience, Sweden). Immunoprecipitates were washed, eluted and subjected to immunoblotting, following essentially our protocol reported previously (20). Blots of IP samples or input fraction were probed with anti-p53 and anti-E2F1 antibodies or anti-γ-tubulin antibody (for input fraction). For western blotting analysis of MEF, p53 and E2F1, we used nuclear extracts of control, transfected or treated cells. After blocking, the membranes were probed with the appropriate antibodies, and blots were visualized using SuperSignal (PIERCE, Rockford, IL, USA).

Senescence induction and senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining

To induce DNA damage-associated cellular senescence, HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells were treated with 100 nM doxorubicin (dox) for 24 h and re-incubated in normal medium for 3 days (for PCR analysis) or 5 days (for staining and protein analyses) according to the protocol reported previously (21). Cells were fixed with 2% formaldehyde/0.2% glutaraldehyde and stained for senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactoside (X-gal) at pH 6.0 as described before (22). SA-β-gal-positive cells were detected by bright-field microscopy.

Animals

The p53 knockout (p53−/−) mice were kindly provided by Dr. Shin Aizawa from RIKEN (Kobe, Japan). The p53-deficient mice were produced through an ordinary knockout (KO) strategy for p53 gene in C57BL/6 mice as described earlier (23). RNA isolates from different tissues of 12-week-old p53−/− mice and age-matched controls were used for Q-PCR analyses. The mice used in this study were housed in a vivarium in accordance with the guidelines of the animal facility center of Kumamoto University. The animals were fed with chow ad libitum. All experiments were performed according to the protocols approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of Kumamoto University (#A19-115).

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, the data were analyzed by Student’s t-test or by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test (JMP software, SAS Institute, NC, USA) as indicated in each figure legend. A P-value of <0.05 is considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

p53 negatively regulates MEF expression in human cell lines and mice tissues

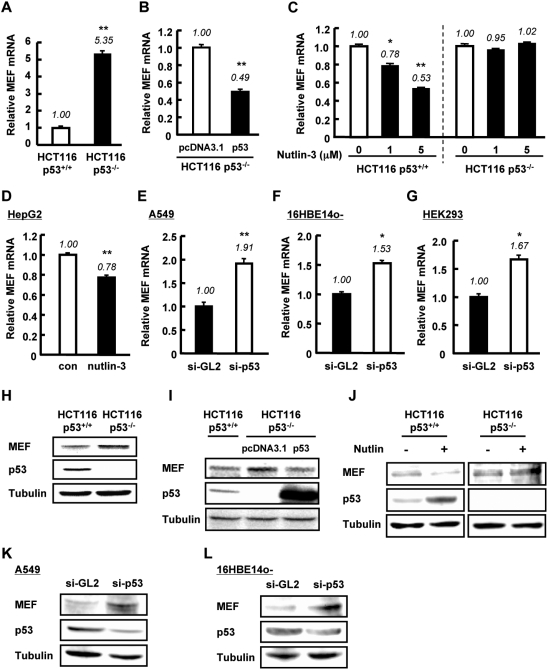

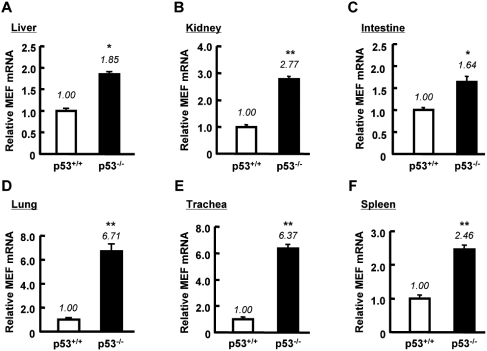

MEF has been implicated in the suppression of p53 expression (16), but it is unknown whether this regulation is reciprocal. To address this question, we first compared the basal level of MEF mRNA in HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells. Interestingly, quantification of mRNA showed that the amount of MEF in HCT116 p53+/+ cells was ∼5-fold lower than in p53−/− cells (Figure 1A). Conventional PCR analysis also showed lower expression of MEF in HCT116 p53+/+ cells than in p53−/− cells (Supplementary Figure S1A). Consistent with these observations, transfection of p53 plasmid in HCT116 p53−/− cells downregulated MEF mRNA level (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure S1B). Treatment with nutlin-3, a specific activator of p53, resulted in a drop in MEF mRNA expression level in p53+/+ cells but not in p53−/− cells (Figure 1C). Treatment of HepG2 cells with nutlin-3 also decreased MEF mRNA level (Figure 1D). Conversely, knockdown of p53 by siRNA in A549, 16HBE14o- and HEK293 cells up–regulated the mRNA expression of MEF (Figure 1E–G). These observations implied that p53 suppresses MEF transcription. To assess whether this decrease also occurs at the protein level, we examined MEF expression in nuclear extracts of HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells. Basal MEF protein level in HCT116 p53+/+ cells was lower than in p53−/− cells (Figure 1H). Exogenous addition of p53 in HCT116 p53−/− cells decreased the expression of MEF (Figure 1I). Moreover, activation of endogenous p53 by nutlin-3, reduced MEF expression in HCT116 p53+/+ cells but had no effect on MEF in p53−/− cells (Figure 1J). Knockdown of p53 by si-RNA in A549 and 16HBE14o- cells increased MEF protein expression (Figure 1K and L). In addition, by using tissues of p53−/− mice, we confirmed the effect of p53 on MEF mRNA expression in vivo. Consistent with the results in human cell lines, MEF mRNA level was higher in various tissues of p53-deficient mice than in those of p53 wild-type mice (Figure 2A–F). These data collectively indicated that p53 downregulates MEF expression.

Figure 1.

p53 downregulates MEF expression in human cell lines. (A) Relative amount of MEF mRNA was examined in HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells. (B) HCT116 p53−/− cells were transfected with control pcDNA3.1 empty vector or p53 plasmid. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, MEF mRNA level was analyzed. (C) HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells were untreated or treated with nutlin-3 for 24 h. Total RNA was isolated for analysis. (D) HepG2 cells were treated with 20 µM nutlin-3 for 48 h then total RNA was recovered. (E–G) A549, 16HBE14o- and HEK293 cells were transfected with si-GL2 (control) or si-p53 as described in ‘Materials and Methods’ section. Total RNA was isolated and analyzed for MEF mRNA. For (A–G) MEF mRNA level, assessed by quantitative RT-PCR, was normalized to GAPDH or 18S rRNA, which served as internal controls. Values are mean ± SD of triplicate measurements. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 versus control cells, assessed by Student’s t-test or ANOVA with Tukey–Kramer test (for (C)). (H) Endogenous MEF and p53 protein expressions in nuclear extracts of HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells were examined by western blotting. (I) HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells were transfected with control pcDNA3.1 empty vector, or p53 plasmid for p53−/− cells. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, nuclear extracts were isolated. (J) HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells were untreated or treated with Nutlin-3 (5 µM) for 24 h, then the nuclear extracts were isolated. (K and L) A549 and 16HBE cells were transfected with si-GL2 (control) or si-p53. Forty-eight hours after transfection, nuclear extracts were isolated. For (H–L), protein levels of MEF and p53 were analyzed by western blotting. γ-tubulin was used as internal control in these experiments.

Figure 2.

MEF mRNA level is upregulated in p53−/− mice tissues. (A–F) Total RNA isolated from the indicated tissues of p53+/+ and p53−/− mice was analyzed for the expression of MEF by real-time quantitative RT–PCR. MEF mRNA level was normalized to mouse 18S rRNA (internal control). Results represent mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 against p53 wild-type mice assessed by Student’s t-test.

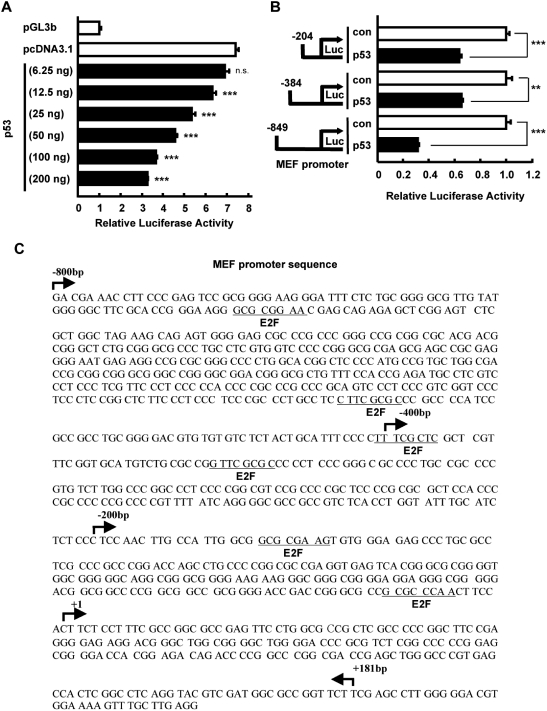

p53 suppresses MEF promoter activity

The effect of p53 on MEF expression was observed at the mRNA level; thus, we focused on MEF promoter to ascertain how p53 downregulates MEF. To establish the influence of p53 on MEF promoter activity, we co-transfected in HCT116 p53−/− cells increasing amounts of p53 expression plasmid and MEF promoter (–849/+181 bp). We found that increased levels of p53 caused a concomitant decline in MEF promoter activity (Figure 3A). Next, to identify the region of MEF promoter that is important for its response to p53, we used three promoter constructs with varying lengths, labeled: −800 bp (–849/+181), −400 bp (–384/+181) and −200 bp (–204/+181) (Figure 3B). These constructs and p53 expression plasmid were co-transfected in p53−/− cells. Reporter assays revealed that activity for all three constructs was downregulated by p53, suggesting that p53 suppresses MEF transcriptional activity by affecting at least the −200 bp proximal region of MEF promoter (Figure 3B). However, in silico analysis of MEF promoter did not reveal any p53 response element within the −800 bp region upstream from the transcription start site. Intriguingly, we found E2F consensus binding sites in this promoter region (Figure 3C). Because it was previously demonstrated that p53 physically interacts with and inhibits the transcriptional activity of E2F1 (24), we hypothesized that p53 indirectly suppresses MEF transcription by affecting E2F1, which could be a novel transcriptional activator of MEF. To assess this possibility, we first investigated the effect of E2F1 on MEF expression and promoter activity.

Figure 3.

p53 suppresses MEF promoter activity. (A) HCT116 p53−/− cells were transiently transfected with MEF (–849/+181 bp) promoter construct or pGL3b vector (0.2 µg) and the indicated amount of p53 plasmid or pcDNA3.1 empty vector. Luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection of plasmids and is expressed as fold activation over the pGL3b vector. Values are the mean ± SE of triplicate platings. ***P < 0.001 versus pcDNA3.1, determined by ANOVA with Tukey–Kramer test. n.s, not significant. (B) HCT116 p53−/− cells were transiently transfected with the indicated MEF promoter constructs (0.2 µg) and p53 plasmid (0.1 µg) or pcDNA3.1 empty vector (as control). Luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection of plasmids and is expressed as fold activation over the pcDNA3.1 vector (con) in each promoter construct. Values are mean ± SE of triplicate platings. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus control, assessed by Student’s t-test. (C) The –849 bp 5′-flanking region of MEF. Nucleotide sequence of 5′-flanking region of human MEF gene is shown. The site indicated (+1) denotes the start site of the first exon. The predicted binding sites for E2F1 are marked on the sequence.

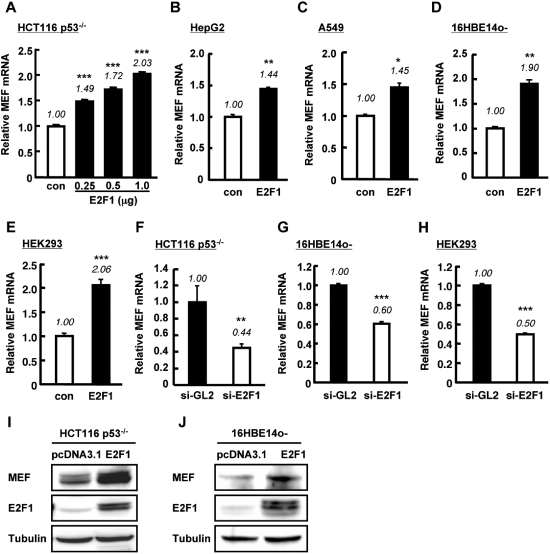

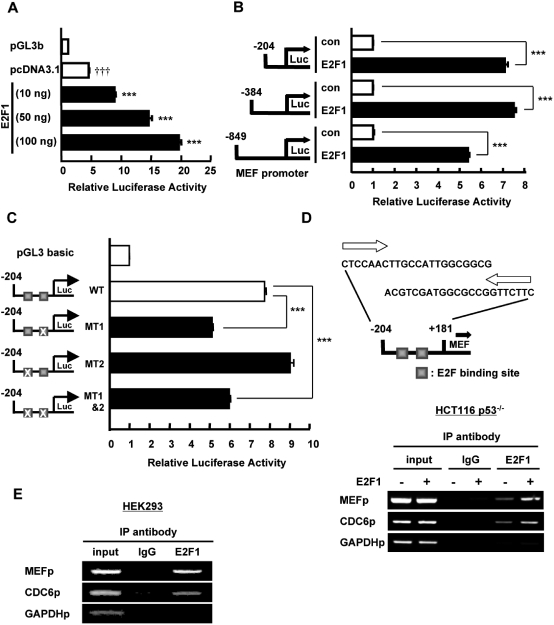

E2F1 is a novel MEF transcriptional activator

Introduction of E2F1 in HCT116 p53−/− cells resulted in dose-dependent increase of MEF mRNA level as determined by Q-PCR (Figure 4A). Similarly, the relative amount of MEF mRNA was upregulated by overexpression of E2F1 in other cell lines tested (Figure 4B–E). In contrast to E2F1 overexpression, siRNA targeting E2F1 induced a drop in basal MEF mRNA level in human epithelial cells (Figure 4F–H). The upregulation of MEF mRNA by E2F1 translated to an increase in MEF protein level as determined by western blotting of nuclear extracts of cells transfected with E2F1 (Figure 4I and J).

Figure 4.

E2F1 upregulates MEF expression in human cell lines. (A–E) Cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3.1 vector (con) or the indicated amount of E2F1 (A) or 1.0 µg E2F1 (B–E). Forty-eight hours after transfection, total RNA was extracted and analyzed for MEF mRNA expression. (F–H) si-GL2 or si-E2F1 (50 nM) was transfected into the indicated cell lines and MEF mRNA expression was assessed 48 h post-transfection. For (A–H) MEF mRNA level, determined by quantitative RT–PCR, was normalized to GAPDH or 18S rRNA (internal control) and expressed as relative amount of mRNA. Values are mean ± SD of triplicate measurements. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 versus control, assessed by ANOVA with Tukey–Kramer (A) or Student’s t-test (B–H). (I–J) MEF and E2F1 protein expressions were examined by western blotting in nuclear extracts of HCT116 p53−/− (I) or 16HBE14o- cells (J) transiently transfected with E2F1 or pcDNA3.1 empty vector. γ-tubulin was used as internal control.

To analyze the effect of E2F1 on MEF transactivation, we co-transfected increasing amounts of E2F1 with MEF promoter (–849/+181 bp) in HCT116 p53−/− cells. E2F1 clearly stimulated MEF transcriptional activity in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5A). To define the region of MEF promoter that is controlled by E2F1, we assessed the effect of E2F1 on three different lengths of MEF promoter construct [as used above (–800 bp, −400 bp and −200 bp)]. These constructs were transfected in HCT116 p53−/− cells together with E2F1 expression vector. Reporter assays revealed that the minimal region of MEF that is activated by E2F1 is at −200 bp upstream from transcription start site (Figure 5B). The −200 bp proximal region contains two E2F binding sites (Figure 3C). Mutation of the E2F site nearest to the start site (MT1) abrogated the basal transcriptional activity of MEF compared to wild-type promoter while mutation of the second E2F site (MT2) did not suppress the basal transactivation of MEF (Figure 5C). Mutation of both sites (MT1&2) diminished the basal promoter activity of MEF in comparison with wild-type to a level similar to that of MT1 (Figure 5C), indicating that E2F binding site 1 in the −200 bp proximal region is important for efficient up-regulation of MEF basal transcription. The residual activity that was not suppressed by the mutation of E2F site could be attributed to the effect of Sp1, which we previously showed as a basal transcriptional activator of MEF that binds to −91/–82 and −63/–54 bp in MEF promoter (12). To establish the association of E2F1 on MEF promoter, we analyzed E2F1 recruitment to MEF promoter by ChIP assay of nuclear lysates from HCT116 p53−/− cells transfected with E2F1 or pcDNA3.1 using ChIP primers that recognize MEF promoter region at −204/+181 bp. Immunoprecipitation with E2F1 antibody but not with control IgG and subsequent PCR reactions revealed the recruitment of endogenous and overexpressed E2F1 to the promoter region of MEF (Figure 5D). In addition, we verified the binding of endogenous E2F1 to MEF promoter in HEK293 cells (Figure 5E). Taken together, we substantiated that E2F1 is a novel MEF transcriptional activator that binds to E2F consensus site in MEF proximal promoter region.

Figure 5.

E2F1 increases MEF promoter activity by binding to E2F site. (A) HCT116 p53−/− cells were transiently transfected with MEF (–849/+181 bp) promoter construct or pGL3b vector (0.2 µg) and the indicated amounts of E2F1 plasmid or pcDNA3.1 empty vector. Luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection and is expressed as fold activation over the pGL3b vector. Values are the mean ± SE of triplicate platings. †††P < 0.001 versus pGL3b; ***P < 0.001 versus pcDNA3.1, determined by ANOVA with Tukey–Kramer. (B) HCT116 p53−/− cells were transiently transfected with the indicated MEF promoter constructs (0.2 µg) and E2F1 plasmid or pcDNA3.1 vector (0.1 µg). Luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection and is expressed as fold activation over the pcDNA3.1 vector in each promoter construct. Values are mean ± SE of triplicate platings. ***P < 0.001 versus control, assessed by Student’s t-test. (C) HCT116 p53−/− cells were transfected with 0.2 µg pGL3b vector or MEF (–200/+181 bp) promoter wild-type (WT), MT1, MT2 or MT1&2. (Left) MT1, MT2 represent MEF (–200/+181 bp) promoter containing mutated E2F site. Luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection and is expressed as fold activation over pGL3b vector. Values are mean ± SE of triplicate platings. ***P < 0.001 versus WT, assessed by ANOVA with Tukey–Kramer test. (D) E2F1 binding on MEF promoter was determined by ChIP assay using nuclear extracts of HCT116 p53−/− cells transiently transfected with E2F1 or pcDNA3.1 vector (1.0 µg). CDC6 promoter was used as positive control and GAPDH promoter was used as negative control for E2F1 binding. Upper panel illustrates the MEF promoter region (–204 bp/+181 bp) in which binding was assessed. (E) Nuclear extract from HEK293 cells was used to assess the endogenous binding of E2F1 on MEF promoter. CDC6 and GAPDH promoters were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

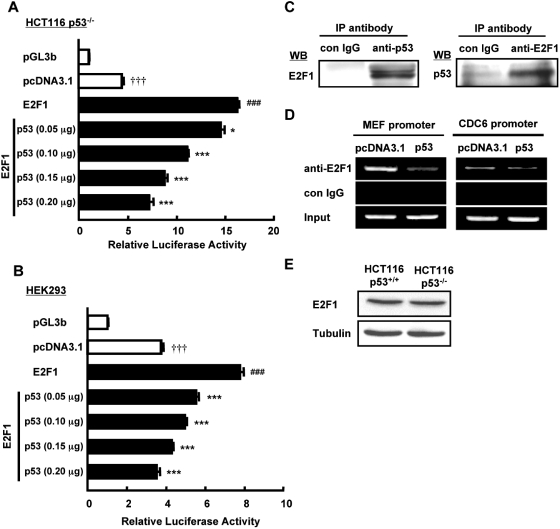

p53 inhibits E2F1 binding to MEF promoter

It has been demonstrated previously that the association of p53 with E2F1 blocks the ability of E2F1 to bind to DNA and transactivate gene expression (25). Having shown that E2F1 binds and activates MEF promoter, we next assessed whether p53 abrogates these effects. Congruent with the above observations, E2F1 significantly stimulated MEF transcriptional activity when E2F1 was co-transfected with MEF promoter (–204/+181 bp) in HCT116 p53−/− and HEK293 cells (Figure 6A and B). However, this positive regulation was titrated away by increasing amounts of co-transfected p53 (Figure 6A and B). To verify the physical interaction between p53 and E2F1, we performed immunoprecipitation (IP) using nuclear extracts of HCT116 p53−/− transfected with p53 and E2F1. Consistent with previous reports (24,26), we confirmed that p53 associates with E2F1 (Figure 6C). To assess the functional consequence of this interaction, we studied its effect on E2F1 binding on MEF promoter. As expected, addition of p53 in HCT116 p53−/− cells substantially lessened the steady-state association of E2F1 on MEF promoter region as detected by ChIP analysis of nuclear extracts (Figure 6D, left). Similar effect of p53 was also observed on CDC6 promoter (Figure 6D, right). Because the expression level of E2F1 is relatively similar in cells with or without p53 (Figure 6E), we ruled out the possibility that the lack of E2F1 binding to promoters in the presence of p53 was due to reduced level of E2F1. Collectively, these data indicated that p53 downregulates MEF transcription by diminishing the recruitment of E2F1 to MEF promoter.

Figure 6.

p53 inhibits E2F1 binding to MEF promoter and reduces E2F1-induced MEF promoter activation. (A and B) HCT116 p53−/− and HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with MEF (–204/+181 bp) promoter construct or pGL3b vector (0.2 µg), pcDNA3.1 or E2F1 (0.1 µg) and the indicated amounts of p53 plasmid. Luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection and is expressed as fold activation over the pGL3b vector. Values are the mean ± SE of triplicate platings. †††P < 0.001 versus pGL3b; ###P < 0.001 versus pcDNA3.1; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001 versus E2F1, determined by ANOVA with Tukey–Kramer. (C) HCT116 p53−/− cells were transiently transfected with p53 and E2F1 plasmids. Nuclear extracts were analyzed for p53-E2F1 association by IP using antibody specific to p53, E2F1 or control mouse IgG. Immunoprecipitates were loaded onto SDS–PAGE gel, blotted and probed with E2F1 or p53 antibodies. (D) HCT116 p53−/− cells were transiently transfected with E2F1 and p53 plasmid or pcDNA3.1 empty vector. Nuclear extracts were isolated and used for ChIP assay to determine E2F1 binding on MEF promoter and CDC6 promoter in the presence or absence of p53. (E) Endogenous protein level of E2F1 was examined in nuclear extracts of HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells. γ-Tubulin was used as internal control.

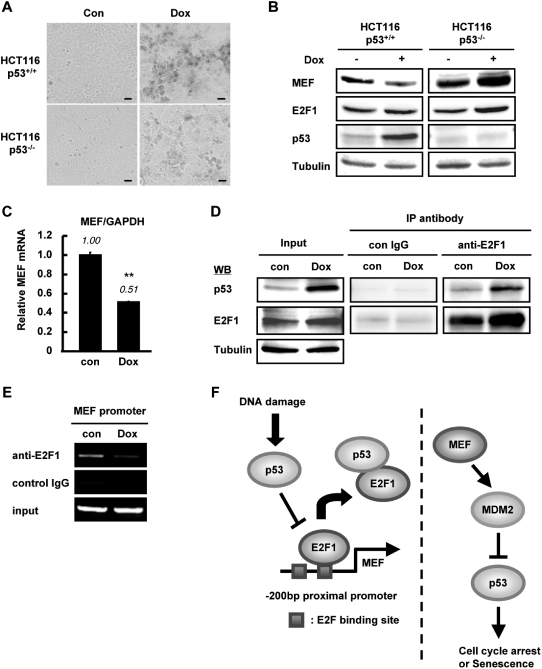

Cellular senescence-induced p53 activation downregulates MEF expression via inhibition of E2F1 binding to MEF promoter

We next asked whether the regulation of MEF by p53 via E2F1 occurs under physiologically relevant setting. Given that MEF has been linked to p53 in the context of cellular senescence (16) and considering our data above, we looked into the possibility that senescence-activated p53 can suppress the expression of MEF. We induced cellular senescence by treating cells with DNA-damaging reagent doxorubicin (dox). Treatment with moderate dose (100 nM) of dox for 24 h and additional incubation for ∼5 days was reported to induce cellular senescence in HCT116 wild-type cells (21). Intense SA-β-gal staining was observed in HCT116 p53+/+ cells while faint staining was seen in p53−/− cells (Figure 7A), consistent with the results obtained by Chang et al. (21). Interestingly, under senescent condition, concomitant with an enhanced level of p53, MEF protein expression was reduced compared with control in HCT116 p53+/+ cells (Figure 7B). On the other hand, dox treatment did not suppress MEF in HCT116 p53−/− cells (Figure 7B), arguing for p53-dependency of MEF downregulation during senescence. MEF mRNA expression in HCT116 p53+/+ cells was also downregulated upon senescence induction (Figure 7C). Next, we assessed the association between E2F1 and p53 during cellular senescence by performing IP analysis. IP using antibody specific to E2F1 and probing with p53 antibody revealed that cellular senescence augmented the physical interaction between E2F1 and p53 (Figure 7D). Notably, we detected by ChIP assay that steady-state binding of E2F1 to MEF promoter was abolished in HCT116 p53+/+ senescent cells (Figure 7E). Taken together, these results suggested that under cellular senescence condition, activated p53 downregulates MEF expression by associating with E2F1 and inhibiting E2F1 binding to MEF promoter.

Figure 7.

p53 suppresses MEF expression during cellular senescence. (A and B) HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells were treated with doxorubicin (Dox) for 24 h and incubated for 5 days to induce cellular senescence. Cells were fixed and stained with X-gal to detect SA-β-gal activity. Stained cells were photographed at phase contrast with 20-fold magnification (Scale bar, 100 µm) (A). The nuclear extracts from Dox-treated or untreated cells were subjected to immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. γ-tubulin was used as internal control (B). (C) HCT116 p53+/+ cells were untreated or treated with Dox for 24 h and incubated for 3 days. Total RNA was recovered and MEF mRNA expression was examined by Q-PCR. Amount of MEF mRNA was normalized to GAPDH and expressed as relative amount compared to control cells. Values are mean ± SD of triplicate platings. **P < 0.01, determined by Student’s t-test. (D) Cellular senescence was induced in HCT116 p53+/+ cells by doxorubicin treatment similar to (A). p53 binding to E2F1 was examined by immunoprecipitation of nuclear extracts. (E) E2F1 binding on MEF promoter was examined by ChIP assay using nuclear extracts of control or Dox-induced senescent HCT116 p53+/+ cells. (F) Negative regulatory mechanism between p53 and MEF. (Left) DNA damage stimulates p53 that enhances its binding to E2F1. This leads to reduced recruitment of E2F1 to the MEF promoter and the suppression of MEF transcription. (Right) MEF upregulates MDM2 (described in ref. 16), which inhibits p53.

DISCUSSION

We have identified a dual, opposing transcriptional regulation mechanism of MEF by E2F1 and p53. E2F1 activates MEF transcription by binding to E2F consensus site in MEF promoter while p53 antagonizes this positive interaction by associating with E2F1 and reducing its DNA-binding activity. The extensive crosstalk between p53 and E2F pathways is well documented (27). It was described earlier by O’Connor et al. (24) that E2F1 and p53 reciprocally inhibit each other’s transcriptional activity through their physical association, probably forming a protein–protein complex and thereby preventing DNA binding. E2F1 and p53 are also known to control genes that influence cell cycle progression (24,27). Indeed, we found here that their interaction (Figures 6C and 7D) affects the regulation of MEF, a molecule that is involved in the transition of cells from G1 to S phase (7) and in driving quiescent hematopoietic stem cells to G1 phase (14). We also noted that exogenous addition of p53 slightly lessened the recruitment of E2F1 to the promoter of CDC6 (Figure 6D), an E2F1 target gene that regulates the early steps of DNA replication (28–30), raising the possibility that p53 interferes with the transcription of genes other than MEF that are targeted by E2F1. Being two pivotal regulators of cell proliferation, the functional interaction between E2F1 and p53 most likely affects cell fate.

Sashida et al. (16) has demonstrated that MEF decreases p53 protein stability by inducing the transcription of MDM2, and MEF also downregulates Rb, an endogenous inhibitor of E2F1. Because the loss of MEF substantially enhanced the senescent phenotype of murine embryonic fibroblasts and activated the p53 function, it was evident that MEF inhibits cellular senescence by suppressing p53 pathway (16) (Figure 7F, right diagram). However, whether this occurs at steady state or induced by pathogenic/pathological condition is still unclear (16). The previous study showing that MEF downregulates p53 combined with our data here showing that MEF mRNA and protein levels were suppressed by p53 implies that a negative regulatory mechanism exists between MEF and p53 pathways. We propose that during DNA damage, p53 is activated and interacts with E2F1, which minimizes E2F1 recruitment to MEF promoter (Figure 7F, left diagram). The lessening of MEF levels may partly contribute to the modulation of cell cycle progression. We showed here that p53 affects MEF transcription indirectly, but the possibility that p53 can also directly affect MEF at the post-translational level cannot be fully ruled out.

Until now, the regulation of MEF protein stability mediated by cyclin A is the only known molecular event by which MEF is controlled especially during cell cycle (7). Our data here indicated that MEF transcription is also influenced by E2F1, an activator E2F family member that affects the cell cycle (31,32). Thus, mechanisms of controlling MEF exist at both transcriptional and post-translational levels. Because E2F1 binds to MEF promoter and mutation of E2F binding site inhibited basal MEF promoter activity, MEF may be considered a target of E2F1 transcription factor. While it is possible that E2F2 and E2F3, which are also trans-activating E2Fs, can affect MEF, we found that specific silencing of E2F1 efficiently suppressed endogenous MEF mRNA level, suggesting a considerable specificity of E2F1 where transactivation is concerned. However, although we observed that MEF transcription was reduced by p53 at the organismal level (Figure 2), the effect of E2F1 on MEF in vivo still awaits verification. As far as we know, MEF is the first member of the Ets transcription factor family to be identified as a direct E2F target gene despite the fact that Ets transcription factors are notable for their roles in cellular growth and proliferation (1). It might not be surprising that future research efforts will unveil direct molecular links between members of E2F and Ets families. Interestingly, it was reported that p53 downregulates Ets1 and Ets2 at transcriptional level, although the molecular mechanism for this downregulation has not been elucidated (33). As our transcription factor search yielded a few E2F consensus sites in their promoter regions (data not shown), E2F might participate in the regulation of Ets1 and Ets2—this possibility remains to be explored.

MEF has been proposed to be a tumor suppressor (13,34) and an oncogene (35). This conundrum has remained unresolved. The differences in the observed functions of MEF may be due to different tumor tissues used and the context on which the activities of MEF were identified. In tumor tissues wherein constitutive activation of E2Fs occurs due to dysregulation in the Rb pathway (36), MEF may contribute to amplify the proliferative function of E2F1 likely by inhibiting p53. However, this supposition may not necessarily mean that MEF is an oncogene (in terms of E2F1 regulation) because E2F1−/− mice have increased susceptibility to tumorigenesis in different tissues (37,38). Being caught in between the complex crosstalk of E2F/Rb and p53 pathways, defining the role of MEF either as tumor suppressor or as oncogene requires further extensive study.

In conclusion, we identified E2F1 as a novel MEF transcriptional activator and p53 as a modulator of this activation. Especially in the context of cellular senescence, as MEF was previously shown to inhibit p53, we have now shown that p53 reciprocally opposes MEF transactivation.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR online.

FUNDING

The Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture (MEXT) of Japan (Grant # 19390045); and the Global COE Program (Cell Fate Regulation Research and Education Unit), MEXT, Japan. Funding for open access charge: The Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

HCT116 p53+/+ and HCT116 p53−/− cell lines were provided by Dr. Bert Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University). 16HBE14o- cells were donated by Dr. Dieter C. Gruenert (California Pacific Medical Center). Wild-type p53 plasmid was supplied by Dr. Hideyuki Saya (Keio University). p53−/− mice were made available by Dr. Shin Aizawa (Laboratory for Animal Resources and Genetic Engineering, Center for Developmental Biology, RIKEN).

REFERENCES

- 1.Sharrocks AD. The ETS-domain transcription factor family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:827–837. doi: 10.1038/35099076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyazaki Y, Sun X, Uchida H, Zhang J, Nimer S. MEF, a novel transcription factor with an Elf-1 like DNA binding domain but distinct transcriptional activating properties. Oncogene. 1996;13:1721–1729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedvat CV, Yao J, Sokolic RA, Nimer SD. Myeloid ELF1-like factor is a potent activator of interleukin-8 expression in hematopoietic cells. [erratum appears in J. Biol. Chem., 2006, 281, 8996] J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:6395–6400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kai H, Hisatsune A, Chihara T, Uto A, Kokusho A, Miyata T, Basbaum C. Myeloid ELF-1-like factor up-regulates lysozyme transcription in epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:20098–20102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu Z, Kim KA, Suico MA, Shuto T, Li JD, Kai H. MEF up-regulates human beta-defensin 2 expression in epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 2004;561:117–121. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacorazza HD, Miyazaki Y, Di Cristofano A, Deblasio A, Hedvat C, Zhang J, Cordon-Cardo C, Mao S, Pandolfi PP, Nimer SD. The ETS protein MEF plays a critical role in perforin gene expression and the development of natural killer and NK-T cells. Immunity. 2002;17:437–449. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00422-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Hedvat CV, Mao S, Zhu XH, Yao J, Nguyen H, Koff A, Nimer SD. The ETS protein MEF is regulated by phosphorylation-dependent proteolysis via the protein-ubiquitin ligase SCFSkp2. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:3114–3123. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3114-3123.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyazaki Y, Boccuni P, Mao S, Zhang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Kiyokawa H, Nimer SD. Cyclin A-dependent phosphorylation of the ETS-related protein, MEF, restricts its activity to the G1 phase of the cell cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:40528–40536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suico MA, Nakamura H, Lu Z, Saitoh H, Shuto T, Nakao M, Kai H. SUMO down-regulates the activity of Elf4/myeloid Elf-1-like factor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2006;348:880–888. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suico MA, Yoshida H, Seki Y, Uchikawa T, Lu Z, Shuto T, Matsuzaki K, Nakao M, Li JD, Kai H. Myeloid Elf-1-like factor, an ETS transcription factor, up-regulates lysozyme transcription in epithelial cells through interaction with promyelocytic leukemia protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:19091–19098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suico MA, Lu Z, Shuto T, Koga T, Uchikawa T, Yoshida H, Matsuzaki K, Nakao M, Li JD, Kai H. The regulation of human beta-defensin 2 by the ETS transcription factor MEF (myeloid Elf-1-like factor) is enhanced by promyelocytic leukemia protein. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;95:466–470. doi: 10.1254/jphs.sc0040077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koga T, Suico MA, Nakamura H, Taura M, Lu Z, Shuto T, Okiyoneda T, Kai H. Sp1-dependent regulation of Myeloid Elf-1 like factor in human epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2811–2816. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seki Y, Suico MA, Uto A, Hisatsune A, Shuto T, Isohama Y, Kai H. The ETS transcription factor MEF is a candidate tumor suppressor gene on the X chromosome. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6579–6586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacorazza HD, Yamada T, Liu Y, Miyata Y, Sivina M, Nunes J, Nimer SD. The transcription factor MEF/ELF4 regulates the quiescence of primitive hematopoietic cells. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Elf SE, Miyata Y, Sashida G, Huang G, Di Giandomenico S, Lee JM, Deblasio A, Menendez S, Antipin J, et al. p53 regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sashida G, Liu Y, Elf S, Miyata Y, Ohyashiki K, Izumi M, Menendez S, Nimer SD. ELF4/MEF activates MDM2 expression and blocks oncogene-induced p16 activation to promote transformation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;29:3687–3699. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01551-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuto T, Furuta T, Oba M, Xu H, Li JD, Cheung J, Gruenert DC, Uehara A, Suico MA, Okiyoneda T, et al. Promoter hypomethylation of Toll-like receptor-2 gene is associated with increased proinflammatory response toward bacterial peptidoglycan in cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2006;20:782–784. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4934fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamura T, Aoyama N, Saya H, Haga H, Futami S, Miyamoto M, Koh T, Ariyasu T, Tachi M, Kasuga M, et al. Induction of Fas-mediated apoptosis in p53-transfected human colon carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 1995;11:1939–1946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koga T, Lim JH, Jono H, Ha UH, Xu H, Ishinaga H, Morino S, Xu X, Yan C, Kai H, et al. Tumor suppressor cylindromatosis acts as a negative regulator for Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced NFAT signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:12546–12554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710518200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taura M, Eguma A, Suico MA, Shuto T, Koga T, Komatsu K, Komune T, Sato T, Saya H, Li JD, et al. p53 regulates Toll-like receptor 3 expression and function in human epithelial cell lines. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01202-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang BD, Xuan Y, Broude EV, Zhu H, Schott B, Fang J, Roninson IB. Role of p53 and p21waf1/cip1 in senescence-like terminal proliferation arrest induced in human tumor cells by chemotherapeutic drugs. Oncogene. 1999;18:4808–4818. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, Medrano EE, Linskens M, Rubelj I, Pereira-Smith O, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsukada T, Tomooka Y, Takai S, Ueda Y, Nishikawa S, Yagi T, Tokunaga T, Takeda N, Suda Y, Abe S, et al. Enhanced proliferative potential in culture of cells from p53-deficient mice. Oncogene. 1993;8:3313–3322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Connor DJ, Lam EW, Griffin S, Zhong S, Leighton LC, Burbidge SA, Lu X. Physical and functional interactions between p53 and cell cycle co-operating transcription factors, E2F1 and DP1. EMBO J. 1995;14:6184–6192. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorensen TS, Girling R, Lee CW, Gannon J, Bandara LR, La Thangue NB. Functional interaction between DP-1 and p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:5888–5895. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nip J, Strom DK, Eischen CM, Cleveland JL, Zambetti GP, Hiebert SW. E2F-1 induces the stabilization of p53 but blocks p53-mediated transactivation. Oncogene. 2001;20:910–920. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polager S, Ginsberg D. p53 and E2f: partners in life and death. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:738–748. doi: 10.1038/nrc2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan Z, DeGregori J, Shohet R, Leone G, Stillman B, Nevins JR, Williams RS. Cdc6 is regulated by E2F and is essential for DNA replication in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:3603–3608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hateboer G, Wobst A, Petersen BO, Le Cam L, Vigo E, Sardet C, Helin K. Cell cycle-regulated expression of mammalian CDC6 is dependent on E2F. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:6679–6697. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohtani K, Tsujimoto A, Ikeda M, Nakamura M. Regulation of cell growth-dependent expression of mammalian CDC6 gene by the cell cycle transcription factor E2F. Oncogene. 1998;17:1777–1785. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iaquinta PJ, Lees JA. Life and death decisions by the E2F transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2007;19:649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Attwooll C, Lazzerini Denchi E, Helin K. The E2F family: specific functions and overlapping interests. EMBO J. 2004;23:4709–4716. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iotsova V, Crepieux P, Montpellier C, Laudet V, Stehelin D. TATA-less promoters of some Ets-family genes are efficiently repressed by wild-type p53. Oncogene. 1996;13:2331–2337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mao S, Frank RC, Zhang J, Miyazaki Y, Nimer SD. Functional and physical interactions between AML1 proteins and an ETS protein, MEF: implications for the pathogenesis of t(8;21)-positive leukemias. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:3635–3644. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao JJ, Liu Y, Lacorazza HD, Soslow RA, Scandura JM, Nimer SD, Hedvat CV. Tumor promoting properties of the ETS protein MEF in ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:4032–4037. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen HZ, Tsai SY, Leone G. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: an exit from cell cycle control. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:785–797. doi: 10.1038/nrc2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamasaki L, Jacks T, Bronson R, Goillot E, Harlow E, Dyson NJ. Tumor induction and tissue atrophy in mice lacking E2F-1. Cell. 1996;85:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Field SJ, Tsai FY, Kuo F, Zubiaga AM, Kaelin WG, Jr, Livingston DM, Orkin SH, Greenberg ME. E2F-1 functions in mice to promote apoptosis and suppress proliferation. Cell. 1996;85:549–561. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.