Abstract

Rationale

Cardiomyocytes switch substrate utilization from fatty acid to glucose under ischemic conditions, however, it is unknown how perturbations in glycolytic enzymes affect cardiac response to ischemia-reperfusion (I/R). Hexokinase (HK) II is a HK isoform that is expressed in the heart and it can bind to the mitochondrial outer membrane.

Objective

We sought to define how HKII and its binding to mitochondria play a role in cardiac response and remodeling after I/R.

Methods and Results

We first showed that HKII levels and its binding to mitochondria are reduced 2 days after I/R. We then subjected the hearts of wild type and heterozygote HKII knockout (HKII+/−) mice to I/R by coronary ligation. At baseline, HKII+/− mice have normal cardiac function, however, they display lower systolic function after I/R compared to wild type animals. The mechanism appears to be through an increase in cardiomyocyte death and fibrosis and a reduction in angiogenesis, the latter is through a decrease in HIF-dependent pathway signaling in cardiomyocytes. HKII mitochondrial binding is also critical for cardiomyocyte survival, as its displacement in tissue culture with a synthetic peptide increases cell death. Our results also suggest that HKII may be important for the remodeling of the viable cardiac tissue as its modulation in vitro alters cellular energy levels, O2 consumption and contractility.

Conclusions

These results suggest that reduction in HKII levels causes altered remodeling of the heart in I/R by increasing cell death and fibrosis and reducing angiogenesis, and that mitochondrial binding is needed for protection of cardiomyocytes.

Keywords: Hexokinase, Ischemia-reperfusion, Mitochondria, Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), Apoptosis

The process of glycolysis starts with glucose uptake by glucose transporters (GLUTs), and phosphorylation by hexokinases (HK). The reaction catalyzed by HKs maintains the concentration gradient required for GLUTs to facilitate the transport of glucose into the cell.1–4 The major GLUTs in the heart are GLUT1 and GLUT4. GLUT1 transgenic mice are resistant to heart failure from pressure overload,5,6 and GLUT4 knockout mice display an increase in hypertrophy.5 However, it is not known how alterations of HKs would affect cardiac response to ischemia-reperfusion (I/R). There are four mammalian HK isozymes: HKI, HKII, HKIII, and HKIV, which is also known as glucokinase.7,8 While HKI is ubiquitously expressed, HKII is primarily expressed in skeletal and cardiac muscle and fat tissue.9 The expression of HKII is regulated by insulin at transcriptional level, and its overexpression in tissue culture results in protection against oxidant-induced cell death.10,11

HKII contains an N-terminal, 21-amino-acid sequence that forms a hydrophobic α helix,12,13 and enables HKII to bind to the outer mitochondrial membrane.14–17 HKII mitochondrial translocation increases in response to insulin and ischemia; a phenomenon also observed with cardioprotective treatments such as ischemia preconditioning (IPC) and morphine.18,19 When the endogenous HKII is displaced from the mitochondria, cells become more susceptible to an injurious insult.11,20,21 Furthermore, overexpression of full length HKII leads to greater protection than a mutant construct that lacks the mitochondrial binding domain.11 The binding to mitochondria may also allow preferable access of HKII to mitochondrially-generated ATP,22 and reduce cellular production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).11,23 This latter function may potentially contribute to the protective effects of HKII.

Although it is well demonstrated that cardiomyocytes switch substrates under ischemic conditions, it is unknown how a reduction in glycolytic enzymes alters cardiac function in response to I/R. We chose to study the effects of a reduction in HKII on cardiac response to I/R injury in intact hearts, and to characterize the mechanism for this process. We first showed that the levels of HKII and its binding to mitochondria are decreased in response to I/R. HKII+/− hearts have normal cardiac function at baseline, however, when they are subjected to I/R, they display increased cardiac dysfunction both in vivo and ex vivo. The mechanism for the lower systolic function appears to be mediated by an increase in cell death and cardiac fibrosis and a reduction in angiogenesis. The decrease in angiogenesis is through a reduction in hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production. HKII binding to mitochondria is important for cardiomyocyte survival, as its displacement in vitro results in an increase in cell death at baseline and in the absence of any injurious agents. Furthermore, modulation of HKII expression in isolated cardiomyocytes results in changes in ATP production, O2 consumption and contractility, suggesting that HKII may be an important player in cardiac remodeling by improving energetic and contractility of the viable cells. These results suggest that HKII and its mitochondrial binding play a role in cardiomyocyte survival and that a decrease in HKII levels in the heart worsens cardiac function after I/R by increasing cardiomyocyte death and fibrosis and reducing angiogenesis.

Methods

HKII+/− mice were mated with wild type (C57BL/6J) to generate HKII+/+ and HKII+/− mice. Experiments were performed on 10 to 12 week-old female and male mice weighing 20–25 g. All mice were maintained and handled in accordance with the Northwestern Animal Care and Use Committee and by the animal ethics committee of the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Animals were initially bred with wild-type C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratories) and subsequently with wild-type offspring, and were backcrossed with C57BL/6J for at least 10 generations. The genomic DNA was prepared using the PureGene DNA isolation kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Gentra Systems, USA). Approximately 10 ng of the genomic DNA was used for PCR using primers against the HKII genomic DNA. The offspring carrying disrupted HKII alleles was identified by PCR amplification with forward primer HK2KO-F2 (5′-ACTCTCCTGCCGCCCTGC-3′) and reverse primers Neo-R1(5′-GTGCCCAGTCATAGCCGAATAGC-3′) and HK2KO-R1 (5′-CCC-CTC-ATC-GCC-ACC-GC-3′).

Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCM) were prepared from 1- to 2-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats and cultured, as described previously.24 Statistical significance was assessed with Anova and the unpaired Student’s t-test. An expanded Methods section is available in the Online Data Supplement at http://circres.ahajournals.org.

Results

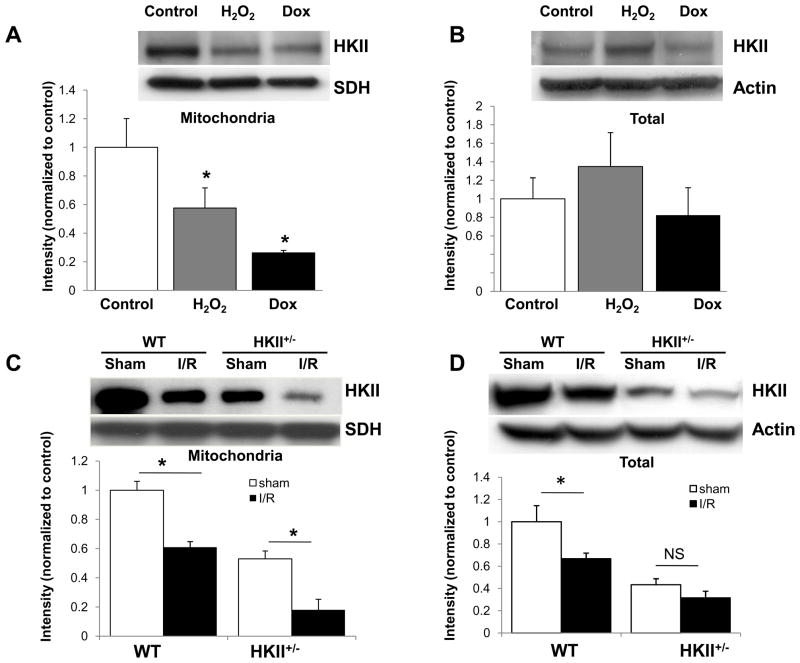

Total and mitochondrial bound HKII levels are reduced in response to I/R

To assess the effects of ischemia and oxidant stress on the total and mitochondrial-bound HKII levels, we exposed NRCM to H2O2 (20 μM, 6h) or doxorubicin (1 μM, 24h). Total HKII levels did not change significantly, but the mitochondrial bound HKII levels were reduced in response to both H2O2 and doxorubicin (Figure 1A and B). We also measured the total and mitochondrial-bound HKII levels in the hearts of wild type and HKII+/− mice subjected to sham or I/R surgery. Consistent with results obtained in vitro, mitochondrial-bound HKII levels were significantly reduced in response to I/R in both wild type and HKII+/− mice (Figure 1C). Furthermore, total HKII levels were also reduced in wild type mice 2 days after I/R, but did not reach statistical significance in HKII+/− mice (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Oxidative stress and I/R reduce HKII-mitochondrial binding. Mitochondria-bound (A) and total HKII levels (B) in NRCM treated with and without H2O2 or doxorubicin. n = 3 independent experiments. (C and D) Mitochondria-bound and total HKII levels in wild type and HKII+/− mice 2 days after I/R injury and in sham-operated mice. *P < 0.05, n = 4–6 samples. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

HKII+/− mice have reduced cardiac function after I/R

To determine the role of HKII in cardiac response to I/R, we studied heterozygote HKII deficient mice. Homozygote deletion of HKII is embryonically lethal, but HKII+/− mice are viable.25,26 As expected, HKII protein levels were significantly reduced in the hearts of HKII+/− mice (Online Figure IA and B). Total HK activity in the heart (which represents both HKI and HKII activity) was also significantly reduced in total cellular extracts and mitochondrial fractions of HKII+/− hearts both at baseline and in response to I/R (Online Figure IC-F). HKI levels were not changed in HKII+/− mice (Online Figure II).

We first assessed cardiac function in WT and HKII+/− mice at baseline using echocardiography and by measurement of hemodynamics. HKII+/− mice displayed similar cardiac size and function compared to WT animals (Online Figure III), suggesting that a reduction in the total and mitochondrial HK activity does not alter cardiac function at baseline.

We then subjected the hearts of WT and HKII+/− mice to I/R by coronary ligation for 45 minutes followed by reperfusion. A summary of the echo results of WT and HKII+/− hearts at baseline and 2, 14, and 28 days after I/R is shown in Table 1. HKII+/− mice had a significantly lower cardiac function after I/R as assessed by ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), and cardiac output (CO) compared to WT animals (Table 1, PFigure 2A). We also assessed cardiac function by invasive hemodynamics. d/dt, a marker of cardiac contractility, was significantly lower in HKII+/− mice compared to WT animals 28 days after I/R (Figure 2B). Consistently, left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP) was higher in HKII+/− mice in response to IR after 28 days (Figure 2C). However, −dP/dt (which represents cardiac relaxation) was similar between HKII+/− and WT mice after I/R (Figure 2D). These data collectively suggest that a reduction in HKII protein results in a more prominent reduction in cardiac contractility compared to WT animals in response to I/R.

Table 1.

Echocardiographic analysis in mice at baseline and 2, 14 and 28 days after I/R.

| parameter | baseline | IR-2 days | IR-14 days | IR-28 days | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (n=9) | HKII+/− (n=9) | WT (n=10) | HKII+/− (n=10) | WT (n=10) | HKII+/− (n=10) | WT (n=10) | HKII+/− (n=10) | |

| HR, min | 417 ± 18.6 | 430 ± 14.1 | 387 ± 16.1 | 390 ± 21.3 | 388 ± 22.2 | 411 ± 18.3 | 382 ± 10.3 | 410 ± 14.4 |

| EF% | 65.31 ± 2.81 | 59.39 ± 2.18 | 44.80 ± 4.88& | 39.25 ± 1.53& | 49.33 ± 2.31& | 38.97 ± 3.55&# | 48.96 ± 1.41& | 35.6 ± 0.46&# |

| FS% | 35.33 ± 2.17 | 32.53 ± 1.36 | 25.60 ± 2.25* | 19.87 ± 1.14&# | 26.16 ± 0.14* | 22.81 ± 3.35& | 24.41 ± 0.79* | 17.77 ± 1.51&# |

| CO, ml/min | 14,69 ± 0.72 | 13.94 ± 1.15 | 12.14 ± 1.14& | 9.18 ± 0.05& | 13.53 ± 0.6 | 9.54 ± 1.76&# | 12.14 ± 1.12 | 7.51 ± 0.52&# |

| IVS, mm | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 0.67 ± 0.07 | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 0.51 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.04 |

| LVPW, mm | 0.55 ± 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.07 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.57 ± 0.03 | 0.57 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.05 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.05* |

| LVID, mm | 3.33 ± 0.28 | 3.56 ± 0.04 | 3.98 ± 0.11* | 4.01 ± 0.15* | 3.91 ± 0.10* | 3.97 ± 0.11* | 3.96 ± 0.16* | 4.14 ± 0.08* |

| Doppler measurement of aortic valve | ||||||||

| P Vel, mm/s | 985.8 ± 25.3 | 971.0 ± 22.8 | 713.6 ± 32.6& | 761.8 ± 44.8& | 811.83 ± 33.04& | 777.8 ± 25.8& | 791.2 ± 35.9& | 678.5 ± 28.9&# |

All measurements were performed at baseline, 2, 14 and 28 days after IR. HR, heart rate; EF%, ejection fraction; FS%, fractional shorting; CO, cardiac output; IVS, end-systolic interventricular septum thickness; LVPW, end-diastolic posterior wall thickness; LVID-s, left ventricular systolic internal diameter; LVID, left ventricular diastolic internal diameter; P Vel, peak velocity. Data are means ± SEM

P < 0.01 vs baseline;

P < 0.05 vs baseline;

P < 0.05 (WT vs HKII+/−).

Figure 2.

HKII+/− mice display lower cardiac function after I/R. Cardiac function was assessed via Doppler echocardiography and by hemodynamic analysis. (A) Summary of FS measurements in WT and HKII+/− mice at baseline and 2, 14, and 28 days after I/R. (B) dP/dt after sham operation or 28 days after I/R based on hemodynamic measurements from a pressure-volume loop in WT and HKII+/− mice. (C) Left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP) in WT and HKII+/− mice 28 days after I/R. (D) −dP/dt in WT and HKII+/− mice. *P < 0.05. n = 8–10 animals. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

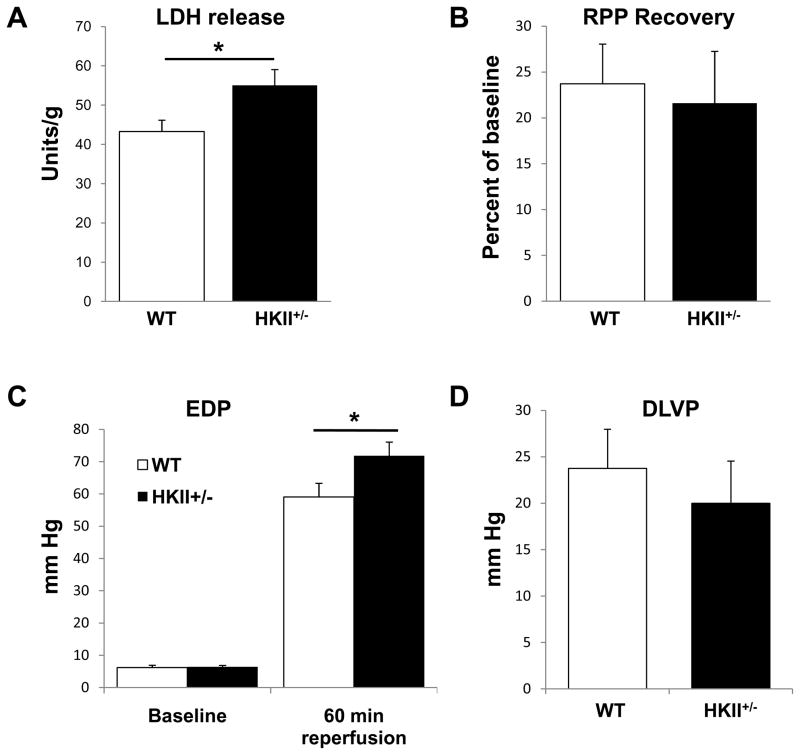

HKII+/− hearts display altered cardiac function in response to I/R ex vivo

To confirm our results, we also performed studies in an ex vivo system. The baseline cardiac characteristics were similar in the WT and HKII+/− mice (Online Table I). When these hearts were subjected to 40 min of ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion, the hearts from the HKII+/− mice demonstrated more injury compared to WT, as measured by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release (Figure 3A). The recovery of the rate-pressure product following I/R was similar between the two groups (Figure 3B), and the development of end-diastolic pressure during ischemia showed a trend of increased contracture for HKII+/− hearts as compared to WT (data not shown). During reperfusion, end-diastolic pressure (EDP) was significantly elevated at 1 h reperfusion for HKII+/− hearts (Figure 3C), while the developed left ventricular pressure (DLVP, peak systolic pressure – EDP) was not changed (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

HKII+/− hearts have lower function and increased cell death after I/R ex vivo. HKII+/− hearts display a higher degree of LDH release and cell injury (A), no change in the rate pressure product (B), a higher end diastolic pressu re (C), and no change in DLVP (D). LDH release and RPP were measured during 60 min reperfusion following 40 min ischemia. EDP was assessed at baseline and after 60 minutes of reperfusion. *P < 0.05, n = 6. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

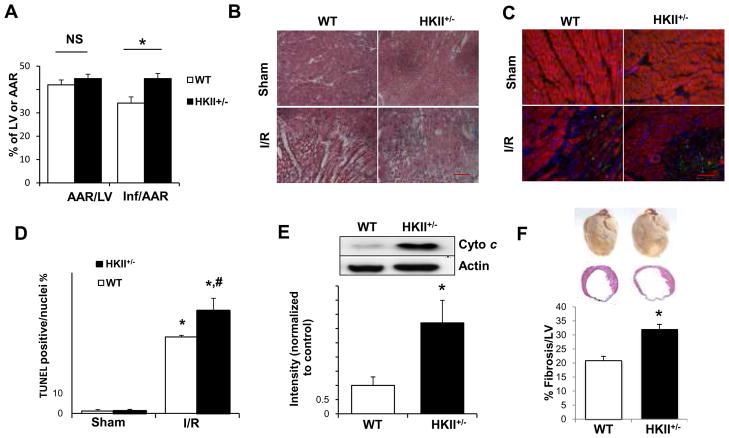

HKII+/− mice display increased cell death and fibrosis and reduced angiogenesis

Since HKII is protective against cell death and the levels of HKII are reduced in HKII+/− hearts, we hypothesized that the reduction in cardiac function in HKII+/− mice is partially due to an increase in cardiomyocyte death. To test this hypothesis, we first assessed the degree of cardiac damage with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC)/thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) staining for the whole heart, and Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining in the peri-infarct zone of the WT and HKII+/− hearts 2 days after I/R. HKII+/− mice had higher degree of damage to their heart compared to WT (Figure 4A and B). To assess if there is an increase in cardiomyocyte apoptosis, we used terminal transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) and measured cytochrome c release into the cytoplasm. HKII+/− mice displayed a significantly higher degree of apoptosis compared to WT mice based on both of these measurements (Figure 4C–E). Furthermore, fibrosis, as assessed by Masson trichrome stain, was significantly higher in HKII+/− mice (Figure 4F). These results all demonstrate an increase in cardiac damage and cell death in HKII+/− mice compared to WT in response to I/R.

Figure 4.

HKII+/− mice display increased cell death and fibrosis after I/R. (A) Summary of area at risk (AAR) per left ventricle (LV) and infarct area (Inf) per AAR 2 days after I/R in WT and HKII+/− hearts. (B) H&E stain of the peri-infarct area demonstrates more cellular damage in the HKII+/− than WT hearts 2 days after I/R. (C) Histological images stained with TUNEL (green), phalloidin-Alexa for actin antibody (red), and DAPI for nuclei (blue) of the peri-infarct zone 2 days after I/R or sham operation in hearts from WT and HKII+/− mice. (D) Summary of TUNEL stain studies. * P < 0.05 vs sham; # P < 0.05 vs WT I/R group. (E) Western blot of cytosolic cytochrome c levels 2 days after I/R in the WT and HKII+/− hearts. A summary of the results is shown below the western blot. (F) Upper panel shows gross examination of WT and HKII+/− hearts 28 days after coronary ligation, and the middle panel shows histological images stained with Masson’s Trichrome. Analysis of fibrosis determined by the ratio of fibrosis length over left ventricle (LV) circumference is shown in the lower panel. *P < 0.05, n = 6. Scale bar = 100 μM. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

In addition to cell death and fibrosis, angiogenesis in the ischemic border zone may affect the remodeling process.27 HKII+/− mice displayed a significantly lower capillary density in the border zone compared to WT animals 28 days after I/R, as assessed by lectin-GSL-1, a marker for endothelium (Figure 5A).28,29 The reduction in angiogenesis was associated with decreased VEGF mRNA levels in the HKII+/− hearts compared to WT animals after I/R (Figure 5B). To confirm that a reduction in HKII leads to a decrease in VEGF levels, we performed in vitro studies and by using RNA interference to reduce HKII levels in NRCM and H9c2 cells (Online Figure IV). Treatment of NRCM with HKII siRNA resulted in a significant decrease in VEGF mRNA and protein levels in the media under hypoxic conditions (Online Figure VA and B).

Figure 5.

HKII+/− mice have less angiogenesis in the peri-infarct zone. (A) Angiogenesis, as assessed by lectin antibody staining, is significantly reduced in the border zone of HKII+/− hearts 28 days after I/R. Green areas represent lectin-positive cells and blue is DAPI for nuclei. Summary of the angiogenesis data is shown next to the images. Five representative high power fields (x40) from the peri-infarctarea of each section were examined, and the number of capillaries was calculated. (B) VEGF mRNA levels in WT and HKII+/− mouse heart 28 days after I/R or sham operation. (C) HIF1α protein levels in WT and HKII+/− mouse heart 2 days after I/R. Band intensity was normalized to tubulin first and then to WT. (D) Western blot of HIF1α in NRCM treated with control or HKII siRNA under hypoxic conditions. The bar graph below the blot represents a summary of the results. Band intensities were normalized to control siRNA. (E) Luciferase assay results on H9c2 cells transfetced with HRE-luciferase or control vector and treated with control or HKII siRNA and then cultured under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n ≥ 3 in each group. Scale bar = 100 μM. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

The mechanism for the decrease in VEGF levels in response to HKII reduction is not clear. Since HIF1α activity and levels are influenced by cellular glucose availability and metabolism,30,31 we hypothesized that the decrease in VEGF in response to a reduction in HKII is through a HIF-dependent pathway. To test this hypothesis, we measured HIF1α protein levels in WT and HKII+/− hearts 2 days after I/R injury. The levels of HIF1α were significantly lower in HKII+/− mice (Figure 5C). Similar results were obtained in NRCM, where treatment with HKII siRNA and hypoxia resulted in a significant decrease in HIF1α protein (Figure 5D) and mRNA levels (Online Figure VC) compared to control siRNA. Furthermore, the mRNA levels of another target of HIF (GLUT1) were also reduced with HKII siRNA treatment in response to hypoxia (Online Figure VD). We also transfected H9c2 cells with a construct containing three sequences of HIF response elements (HRE) attached to a luciferase reporter sequence or a control vector, followed by treatment with HKII siRNA. HKII knockdown resulted in a reduction in HIF activity in normoxia and hypoxia (Figure 5E), further supporting that HKII can influence HIF activity. Overall, these results suggest that a reduction in HKII reduces angiogenesis and VEGF levels likely through a HIF dependent pathway.

Displacement of HKII from mitochondria increases cardiomyocyte death

We next studied the mechanism for the increase in cell death in HKII+/− mice in response to I/R. HKII mitochondrial binding is important for cell survival, and the displacement of the protein from the mitochondria makes cancer cells susceptible to cell injury.20,21 We thus assessed the role of HKII binding to the mitochondria in cardiomyocyte death. HKII was displaced from the mitochondria in NRCM using a cell permeable peptide (n-HKII) against its N-terminal hydrophobic domain. Treatment with 5 μM of the peptide resulted in a small but non-significant reduction in the mitochondrial bound HKII; while the 20 μM concentration of the peptide resulted in almost complete displacement of HKII from the mitochondria (Figure 6A). Consistent with the levels of displacement, the 20 μM dose resulted in a significant reduction in the mitochondrial membrane potential, as assessed by TMRE fluorescence (Figure 6B). Treatment with the HKII peptide also resulted in a dose dependent increase in cell death as assessed by trypan blue and propidium exclusion (Figure 6C and Online Figure VIA, respectively). Treatment with HKII peptide did not results in changes in the levels of mitochondrial HKI (Online Figure VIB). These results are in contrast to those obtained in cancer cells, where treatment with HKII peptide does not increase cell death but makes the cells more susceptible to injury.20,32 Thus, we conclude that HKII binding to mitochondria is important for cardiomyocyte viability, and decreased mitochondrially bound HKII in HKII+/− mice could explain the higher degree of cell death in those mice in response to I/R.

Figure 6.

Displacement of endogenous HKII from mitochondria increases cell death. (A) Compared to a control peptide, 2 hour treatment with 5 μM of an HKII-competing peptide (n-HKII) resulted in a non-significant reduction in the amount of mitochondrially bound HKII in NRCM (left), while20 μM concentration resulted in almost complete displacement of HKII from the mitochondria (right). (B) Treatment with the n-HKII peptide for 2 hours leads to a dose dependent decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential, as measured by flow analysis of TMRE fluorescence. (C) Treatment with the n-HKII peptide for 2 hours leads to a dose dependent increase in cell death compared to control, as assessed by trypan blue exclusion studies. *P < 0.05 vs control peptide, n = 3 in each group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Modulation of HKII levels alter cardiomyocyte energy levels and contractility

To better characterize the mechanism for the reduction in cardiac function in HKII+/− mice, we assessed the role of HKII in cardiomyocyte energy production and contractility. We hypothesized that since HKII is a rate limiting enzyme in glucose metabolism, it plays a major role in cellular ATP production, O2 consumption and cardiac contractility, and a reduction in its levels results in decreased contractility of the viable cells and altered remodeling after I/R. To test this hypothesis, we overexpressed or downregulated HKII in NRCM using adenoviral and RNA interference techniques and assessed ATP levels and O2 consumption. Overexpression of HKII resulted in an increase in both ATP levels and O2 consumption in NRCM (Figure 7A and C), while its downregulation reduced both of these parameters (Figures 7B and D). We then assessed cellular contractility by measuring Ca2+ transients. HKII overexpression was associated with greater transient amplitude, duration at 50% recovery, integral, fall time, and half width (Online Figure VII). These data suggest that HKII plays an important role in cardiomyocyte cellular energy production and contractility and that the reduction in cardiac function in HKII+/− mice after I/R may be partly due to lower energy production and cellular contractility of the viable cells.

Figure 7.

HKII overexpression increases ATP production and O2 consumption, while its downregulation has the opposite effect. (A) HKII was overexpressed in NRCM using an adenovirus and ATP levels were measured. Cells overexpressing HKII displayed significantly higher ATP levels compared to cells overexpressing GFP alone. (B) NRCM were treated with control or HKII siRNA and ATP levels were measured after 48 hours. HKII downregulation resulted in a reduction in cellular ATP levels when normalized to cell number. (C) Summary of baseline and maximal O2 consumption in NRCM treated with GFP and HKII adenovirus. HKII overexpression resulted in a higher maximal O2 consumption in NRCM compared to GFP transfected live cells. (D) HKII downregulation resulted in a decrease in both basal and maximal O2 consumption. *P < 0.05, n ≥ 3 experiments. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Discussion

In this paper, we examined the hearts of HKII+/− mice in response to I/R. We hypothesized that since glucose becomes the major substrate for energy production in hypoxic conditions, a perturbation in its phosphorylation would lead to a more exacerbated damage from I/R. HKII is of particular interest because: 1) it becomes the rate limiting enzyme in glucose metabolism in the heart under hyperinsulinemic conditions, 2) its overexpression is protective against cell death in tissue culture, 3) it can bind to the mitochondria and this binding contributes to the protective effects of the enzyme, 4) it has been shown to reduce the cellular levels of ROS, and 5) cardioprotection by ischemic preconditioning increases HKII binding to mitochondria.19,33

Our results demonstrated that hearts from HKII+/− mice display lower systolic function after I/R. We then showed that HKII+/− animals display: 1) an increase in cell death, suggesting that a reduction in HKII leads to more cardiomyocyte injury in response to ischemia, 2) an increase in fibrosis, and 3) a reduction in angiogenesis. For the latter process, we demonstrated that the mechanism appears to be through a reduction in a HIF-dependent production of VEGF in cardiomyocytes. We further show that the HKII binding to mitochondria is required for survival of cardiomyocytes and that a reduction in the mitochondrially-bound HKII in HKII+/− mice is possibly a major contributor to cell death after I/R. Finally, our results demonstrate that modulation of HKII in NRCM leads to a change in cardiomyocyte ATP production, O2 consumption, and contractility, suggesting that HKII may play a role in cardiac remodeling likely by providing more energy and altering the contractility of viable cardiomyocytes. These results suggest that stimulation of HKII may lead to an increase in glucose metabolism and energy production, a decrease in cardiomyocyte cell death and fibrosis, and an increase in angiogenesis in response to I/R. Collectively, these changes would all lead to an improvement in cardiac function and remodeling of the heart after I/R. Although this study focuses on HKII in the heart, it is possible that defects in HKI could have similar effects as HKII.

The product of glucose phosphorylation, i.e., glucose-6-phosphate, can undergo glycolysis or glycogen synthesis, or alternatively enter the pentose phosphate or hexosamine pathways. Thus, one may argue that a reduction in HKII activity in HKII+/− mice results in reduced substrate availability for at least four different pathways, and our data do not differentiate which one of these pathways plays a role in the phenotypic abnormality of HKII+/− mice in response to I/R. Cardiac glucose uptake, glycogen content and glucose metabolism in HKII+/− mice have been studied in the past and shown to be similar to wild type animals at baseline.25,34 However, HKII+/− mice display lower glucose metabolism in response to stress conditions such as exercise, while glycogen content may actually be increased under these conditions.25,34 Thus, we propose that the attenuated cardiac function in response to I/R in HKII+/− mice is due to decreased glucose metabolism that may occur in these mice in response to low oxygen, in addition to decreased mitochondrial-bound HKII. Our results along with those reported before argue against reduced glycogen content to contribute to the worsened cardiac function in HKII+/− mice in response to I/R.

HKII+/− mice displayed lower angiogenesis in response to I/R than WT mice. Since the animals have HKII knockout in every tissue, it is difficult to determine whether the reduction in HKII levels in cardiomyocytes versus endothelial cells is responsible for the decrease in angiogenesis. To better define the role of cardiomyocytes in the reduction of angiogenesis in HKII+/− mice, we studied the effects of HKII knockdown in isolated cardiomyocytes on VEGF production. Our results showed that HKII knockdown results in a decrease in VEGF levels under hypoxic conditions. We then studied the mechanism for a reduction in VEGF production in response to HKII knockdown. Previous studies had shown that a reduction in glucose results in a decrease in the expression of HIF-dependent genes and the HIF1α response to hypoxia,31 and that glucose metabolites like pyruvate inactivate HIF1α decay.30 We thus hypothesized that a reduction in VEGF and angiogenesis in response to HKII knockdown is through a HIF-dependent pathway. Our results demonstrate that treatment of cells with HKII siRNA results in reduced HIF levels and activity. Thus, we conclude that decreased angiogenesis in HKII+/− mice may be through a reduction in HIF activity and VEGF production.

Cardiomyocyte contractility is highly dependent on the ATP levels within the cell. Thus, a reduction in HKII levels may hinder the ability of cardiomyocytes in the remote area to increase their contractility and overall remodeling of the heart. We assessed this possibility by overexpressing and downregulating HKII in isolated cardiomyocytes. The downregulation of HKII in NRCM resulted in lower ATP levels and O2 consumption, while HKII overexpression had the opposite effect and increased cardiomyocyte contractility. Thus, the decrease in cardiac function in HKII+/− mice after I/R could be partially due to a reduction in cardiomyocyte contractility from a decrease in energy production. It is important to mention that although our data suggest an association between cardiac contractility and bioenergetic compromise through reductions in HKII, it does not establish a direct cause-and-effect relationship.

In summary, our results indicate that the HKII+/− mice are more susceptible to ischemic injury to their heart. This is due to an increase in cell death and fibrosis, a decrease in angiogenesis and possibly a reduction in the contractility of the viable cardiomyocytes due to reduced energy production. Furthermore, the binding of HKII to mitochondria plays an important role in cardiomyocyte survival and protection against cell death. Our results provide the first description of the role of HKII and its mitochondrial binding in acute cardiac I/R injury and subsequent remodeling of the intact heart. Thus, in addition to their role in cancer, HKII and its mitochondrial binding play a prominent role in the pathogenesis of ischemic heart disease. These data suggest that targeting HKII and its cellular distribution may provide a novel therapeutic option in ischemic heart disease.

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Cardiomyocytes switch substrate utilization from fatty acid to glucose under stress conditions, such as ischemia and hypertrophy.

Hexokinases II (HKII) carries out the first step in glycolysis by phosphorylating glucose in muscle and fat tissue, and can bind to the outer mitochondrial membrane.

Overexpression of HKII or increasing its mitochondrial binding protects against cell death.

Homozygote deletion of HKII is embryonically lethal, but HKII+/− mice are viable and have minimal abnormalities.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Mice with heterozygote deletion of HKII have normal cardiac function at baseline, but display lower systolic function after ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) compared with wild type animals.

Following I/R, HKII+/− mice display a reduction in angiogenesis through a decrease in HIF-dependent pathway signaling, and an increase in cell death and fibrosis.

Displacing HKII from mitochondria in tissue culture increases cell death, suggesting that the binding of HKII to the mitochondria is critical for cardiomyocyte survival.

It is well accepted that cardiomyocytes switch substrate preference from fatty acid to glucose in ischemia. However, the effects of alterations in glycolytic enzymes on cardiac response to ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) are not known. Hexokinase (HK)-II is the major isoform expressed in the heart and can bind to the mitochondrial outer membrane. This study shows that HKII+/− mice display lower systolic function after I/R compared to wild type animals. They show a reduction in angiogenesis via reduced HIF signaling, as well as an increase in cardiomyocyte death and fibrosis. Additionally, binding of HKII to the mitochondria appears to be critical for cardiomyocyte survival, because dissociation of the protein from the mitochondria in tissue culture increased cell death. HKII may also be important for the remodeling of the viable cardiac tissue as its modulation in vitro altered cellular energy levels and contractility. Our results suggest that targeting HKII or its cellular distribution may provide a novel therapeutic option for treating ischemic heart disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Navdeep Chandel (Northwestern University) for the HRE-luciferase construct.

Sources of Funding

H.A. is supported by NIH grant K08 HL079387, R01 HL087149, and the American Heart Association. R.W. and E.W. are supported by the American Heart Association.

Abbreviations

- HK

hexokinase

- GLUT

glucose transporter

- I/R

ischemia-reperfusion

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- HKII+/−

heterozygote HKII deficient mice

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- NRCM

neonatal rat cardiomyocytes

- WT

wild type

- EF

ejection fraction

- FS

fractional shortening

- CO

cardiac output

- LVEDP

left ventricular end diastolic pressure

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase LDH

- EDP

end-diastolic pressure

- TUNEL

terminal transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- HRE

HIF response elements

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Bell GI, Burant CF, Takeda J, Gould GW. Structure and function of mammalian facilitative sugar transporters. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19161–19164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gould GW, Holman GD. The glucose transporter family: structure, function and tissue-specific expression. Biochem J. 1993;295 (Pt 2):329–341. doi: 10.1042/bj2950329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueckler M. Facilitative glucose transporters. Eur J Biochem. 1994;219:713–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Printz RL, Osawa H, Ardehali H, Koch S, Granner DK. Hexokinase II gene: structure, regulation and promoter organization. Biochem Soc Trans. 1997;25:107–112. doi: 10.1042/bst0250107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abel ED, Kaulbach HC, Tian R, Hopkins JC, Duffy J, Doetschman T, Minnemann T, Boers ME, Hadro E, Oberste-Berghaus C, Quist W, Lowell BB, Ingwall JS, Kahn BB. Cardiac hypertrophy with preserved contractile function after selective deletion of GLUT4 from the heart. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1703–1714. doi: 10.1172/JCI7605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao R, Jain M, Cui L, D’Agostino J, Aiello F, Luptak I, Ngoy S, Mortensen RM, Tian R. Cardiac-specific overexpression of GLUT1 prevents the development of heart failure attributable to pressure overload in mice. Circulation. 2002;106:2125–2131. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034049.61181.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Middleton RJ. Hexokinases and glucokinases. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990;18:180–183. doi: 10.1042/bst0180180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ureta T. The comparative isozymology of vertebrate hexokinases. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1982;71:549–555. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(82)90461-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson JE. Isozymes of mammalian hexokinase: structure, subcellular localization and metabolic function. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:2049–2057. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad A, Ahmad S, Schneider BK, Allen CB, Chang LY, White CW. Elevated expression of hexokinase II protects human lung epithelial-like A549 cells against oxidative injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;283:L573–584. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00410.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun L, Shukair S, Naik TJ, Moazed F, Ardehali H. Glucose phosphorylation and mitochondrial binding are required for the protective effects of hexokinases I and II. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1007–1017. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00224-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sui D, Wilson JE. Structural determinants for the intracellular localization of the isozymes of mammalian hexokinase: intracellular localization of fusion constructs incorporating structural elements from the hexokinase isozymes and the green fluorescent protein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;345:111–125. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie GC, Wilson JE. Rat brain hexokinase: the hydrophobic N-terminus of the mitochondrially bound enzyme is inserted in the lipid bilayer. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;267:803–810. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aflalo C, Azoulay H. Binding of rat brain hexokinase to recombinant yeast mitochondria: effect of environmental factors and the source of porin. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1998;30:245–255. doi: 10.1023/a:1020544803475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azoulay-Zohar H, Israelson A, Abu-Hamad S, Shoshan-Barmatz V. In self-defence: hexokinase promotes voltage-dependent anion channel closure and prevents mitochondria-mediated apoptotic cell death. Biochem J. 2004;377:347–355. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiek C, Benz R, Roos N, Brdiczka D. Evidence for identity between the hexokinase-binding protein and the mitochondrial porin in the outer membrane of rat liver mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;688:429–440. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(82)90354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linden M, Gellerfors P, Nelson BD. Pore protein and the hexokinase-binding protein from the outer membrane of rat liver mitochondria are identical. FEBS Lett. 1982;141:189–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Southworth R, Davey KA, Warley A, Garlick PB. A re-evaluation of the roles of hexokinase I and II in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00664.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zuurbier CJ, Eerbeek O, Meijer AJ. Ischemic preconditioning, insulin, and morphine all cause hexokinase redistribution. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H496–499. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01182.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Majewski N, Nogueira V, Bhaskar P, Coy PE, Skeen JE, Gottlob K, Chandel NS, Thompson CB, Robey RB, Hay N. Hexokinase-mitochondria interaction mediated by Akt is required to inhibit apoptosis in the presence or absence of Bax and Bak. Mol Cell. 2004;16:819–830. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pastorino JG, Shulga N, Hoek JB. Mitochondrial binding of hexokinase II inhibits Bax-induced cytochrome c release and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7610–7618. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pastorino JG, Hoek JB. Hexokinase II: the integration of energy metabolism and control of apoptosis. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:1535–1551. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.da-Silva WS, Gomez-Puyou A, de Gomez-Puyou MT, Moreno-Sanchez R, De Felice FG, de Meis L, Oliveira MF, Galina A. Mitochondrial bound hexokinase activity as a preventive antioxidant defense: steady-state ADP formation as a regulatory mechanism of membrane potential and reactive oxygen species generation in mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39846–39855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403835200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ardehali H, O’Rourke B, Marban E. Cardioprotective role of the mitochondrial ATP-binding cassette protein 1. Circ Res. 2005;97:740–742. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000186277.12336.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fueger PT, Lee-Young RS, Shearer J, Bracy DP, Heikkinen S, Laakso M, Rottman JN, Wasserman DH. Phosphorylation barriers to skeletal and cardiac muscle glucose uptakes in high-fat fed mice: studies in mice with a 50% reduction of hexokinase II. Diabetes. 2007;56:2476–2484. doi: 10.2337/db07-0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heikkinen S, Pietila M, Halmekyto M, Suppola S, Pirinen E, Deeb SS, Janne J, Laakso M. Hexokinase II-deficient mice. Prenatal death of homozygotes without disturbances in glucose tolerance in heterozygotes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22517–22523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kocher AA, Schuster MD, Szabolcs MJ, Takuma S, Burkhoff D, Wang J, Homma S, Edwards NM, Itescu S. Neovascularization of ischemic myocardium by human bone-marrow-derived angioblasts prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis, reduces remodeling and improves cardiac function. Nat Med. 2001;7:430–436. doi: 10.1038/86498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Renault MA, Roncalli J, Tongers J, Misener S, Thorne T, Jujo K, Ito A, Clarke T, Fung C, Millay M, Kamide C, Scarpelli A, Klyachko E, Losordo DW. The Hedgehog transcription factor Gli3 modulates angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2009;105:818–826. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers MS, Birsner AE, D’Amato RJ. The mouse cornea micropocket angiogenesis assay. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2545–2550. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu H, Dalgard CL, Mohyeldin A, McFate T, Tait AS, Verma A. Reversible inactivation of HIF-1 prolyl hydroxylases allows cell metabolism to control basal HIF-1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41928–41939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508718200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou J, Hara K, Inoue M, Hamada S, Yasuda H, Moriyama H, Endo H, Hirota K, Yonezawa K, Nagata M, Yokono K. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 by glucose availability under hypoxic conditions. Kobe J Med Sci. 2008;53:283–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pastorino JG, Hoek JB, Shulga N. Activation of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta disrupts the binding of hexokinase II to mitochondria by phosphorylating voltage-dependent anion channel and potentiates chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10545–10554. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurel E, Smeele KM, Eerbeek O, Koeman A, Demirci C, Hollmann MW, Zuurbier CJ. Ischemic preconditioning affects hexokinase activity and HKII in different subcellular compartments throughout cardiac ischemia-reperfusion. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1909–1916. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90537.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fueger PT, Heikkinen S, Bracy DP, Malabanan CM, Pencek RR, Laakso M, Wasserman DH. Hexokinase II partial knockout impairs exercise-stimulated glucose uptake in oxidative muscles of mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E958–963. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00190.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.