Abstract

Purpose

A new strain of the H1N1 subtype of influenza A virus resulted in a pandemic outbreak. In South Korea, cases of pandemic influenza have increased. Therefore, we explored perception or preventive behaviors for this virus in hospital employees and outpatients.

Materials and Methods

Data was collected from hospital employees and outpatients at three university hospitals located in Daegu, Gyeongju in South Korea between the 21st and 30th of September, 2009 using a self-administrated questionnaire. We estimated perception by components of The Health Belief Model (HBM), preventive behaviors consisted of avoidance behaviors, and the recommended behaviors by the Korea Center of Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC). Desire for vaccination was identified.

Results

The 1,837 participants comprised hospital employees (n = 880, 47.9%) and outpatients (n = 957, 52.1%). Of all hospital employees, 491 (55.8%) and 708 (80.5%) perceived susceptibility of the pandemic influenza and benefits of the preventive behaviors, respectively. Among all outpatients, 490 (51.2%) and 651 (68.0%) perceived susceptibility of the pandemic influenza and benefits of the preventive behaviors, respectively. Recommended preventative behaviors were adopted by 674 (76.6%) of hospital employees and 631 (65.9%) of outpatients. Vaccination was desired by 479 (54.4%) of hospital employees and 484 (50.6%) of outpatients. Factors influencing preventative behaviors included gender, economic status (for hospital employees) and educational level (for outpatients). All HBM components except perception of barriers were associated with the preventive behaviors in both groups.

Conclusion

The majority of the surveyed hospital employees and outpatients perceived the benefits of preventive behaviors for pandemic influenza and performed them.

Keywords: Influenza A virus, H1NI subtype, perception, behavior

INTRODUCTION

A new strain of influenza A virus, H1N1 subtype as "Pandemic H1N1 influenza", is a highly infectious virus. The World Health Organization (WHO) raised pandemic alerts level for this virus to phase 6 in June 2009.1 In South Korea, The Korea Center of Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) has recommended preventive behaviors for the pandemic influenza such as washing hands, using a tissue when coughing or sneezing, and reducing outings when respiratory symptoms or febrile sensations have developed. Nevertheless, the first mortality due to H1N1 was reported in South Korea in August 2009, followed within a month by hundreds of reported cases.2

During the WHO phase 5, less than half of the public responders had anxiety for pandemic influenza or thought that pandemic influenza seriously affected their health.3,4 The performing rate of recommendation action for preventing the pandemic influenza was below 40%.3 Any studies about perception or preventive behaviors for pandemic influenza have not been reported in South Korea. Therefore, we explored perception and performance of preventive behaviors for pandemic influenza in WHO phase 6, including the desire of pandemic influenza vaccination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data was collected using self-administered questionnaires from hospital employees and outpatients at three university hospitals located in Daegu, Gyeongju in South Korea between the 21st and 30th of September, 2009. We conveniently selected participants who were over the age of 18, and regarded hospital employees as doctors, nurses, hospital administrators, and technicians of radiology or laboratory.

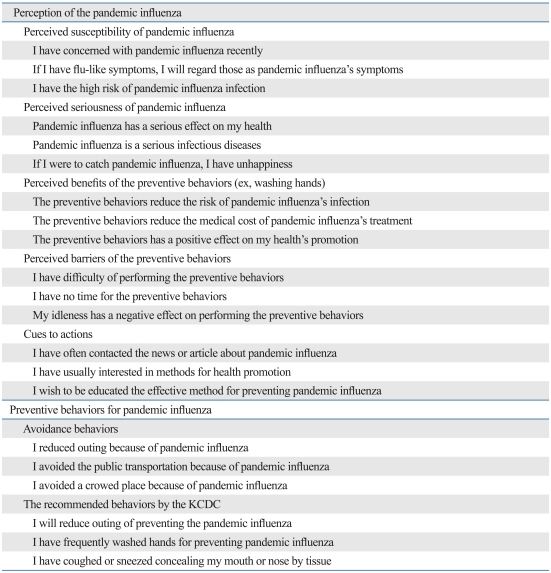

The questionnaire included general characteristics (gender, sex, married state, education state, and economic state), perceptions, preventive behaviors, and vaccination's desire for the pandemic influenza. We estimated perception of pandemic influenza using components of the Health Belief Model (HBM). The HBM consisted of five components: susceptibility, seriousness, perceived benefit of action, perceived barriers of action, and cues of action.5 We selected three questions per component among the Korean translation form of the HBM identified reliability and validity,6 modified contents to assess the perception of the pandemic influenza. Preventative behaviors were assessed by six questions that addressed avoidance behaviors and KCDC recommended behaviors.2 We measured these questions with a 5 point Likert scale marked from "not agree" as 1 to "strongly agree" as 5 (Table 1). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dongguk University Gyeongju Hospital.

Table 1.

Survey Items for Perceptions and Preventive Behaviors

KCDC, Korea Center of Disease Control and Prevention.

All participants were classified as hospital employees and outpatients. Each group of respondents was calculated frequency and percentage. The Crohnbach alpha scores of the questions concerning perception and preventive behaviors were calculated to identify reliability of HBM. To estimate respondent's perception of pandemic influenza, the points of three of the relevant questions were combined. When the total exceeded 9 points, the respondent was judged to comply with the HBM. The same approach was used to assess avoidance behaviors and compliance with KCDC recommendations. A respondent was judged to desire vaccination when the response to the pertinent question exceeded 4 points. Factors related to the performance of preventative behaviors in each group of respondents were identified by multivariable logistic regression analysis using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The significance level was 0.05.

RESULTS

During the study period, 11 deaths due to H1N1 pandemic influenza were reported, with a weekly incidence of 7 cases per 1,000 people reported. At the time of the pandemic, a vaccination program has not yet been implemented in Korea.2

Of the 2,132 participants recruited for the study, 295 were excluded due to incomplete data. The final participant total was 1,837, and comprised 880 hospital employees (47.9% of total) and 957 outpatients (52.1%).

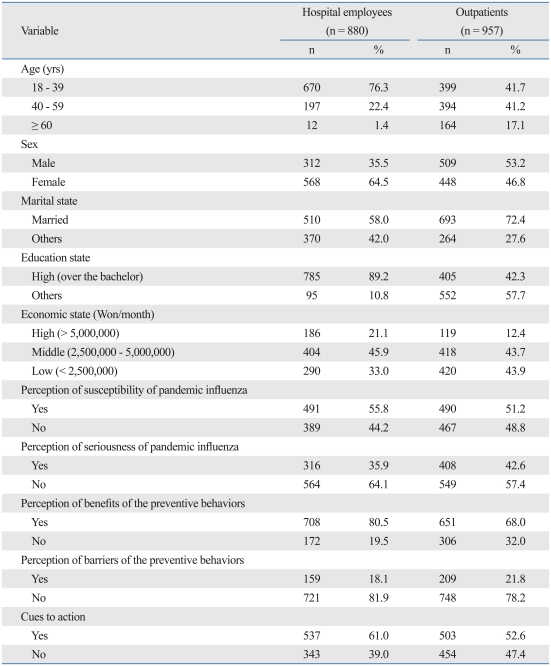

Of the hospital employees, 670 (76.3%) were below 40 years old. Of the hospital employees, females were more prevalent than males (64.5% versus 35.5%, respectively). The majority of the respondents were married (n = 510, 58.0%) and had attained advanced education (n = 785, 89.2%). A minority of respondents had a high economic status (n = 186, 21.1%).

Of the outpatients, 399 (41.7%) were below 40 years old, 394 (41.2%) were 40-59-years-of-age and 164 (17.1%) were over 60 years old. Males and females comprised 53.2% and 46.8% of the respondents, respectively. The majority were married (72.4%). A minority had an advanced level of education (n = 405, 42.3%) and a high economic standing (n = 119, 12.4%).

The reliability of the questions were verified by a Cronbach alpha scores of 0.79 for total HBM components, 0.67 for avoidance behaviors and 0.75 for KCDC recommended behaviors.

Of the hospital employee participants, 491 (55.8%) perceived their susceptibility to the pandemic influenza, 316 (35.9%) regarded pandemic influenza as a serious health threat and 708 (80.5%) perceived the preventative measures as beneficial. One hundred fifty nine of the hospital employee respondents (18.1%) perceived the barrier concerning preventative behaviors and 537 (61.0%) had assimilated cues concerning preventative behavior.

Of the outpatients, 490 (51.2%) and 408 (42.6%) perceived their susceptibility to the pandemic and the seriousness of pandemic influenza, respectively. Six hundred fifty one of the respondents (68.0%) perceived the preventative measures as beneficial and 209 (21.8%) perceived the barrier concerning preventative behaviors. Five hundred three respondents (52.6%) had assimilated cues concerning preventative behavior (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic Data and Perceptions of the Pandemic Influenza in All Participants

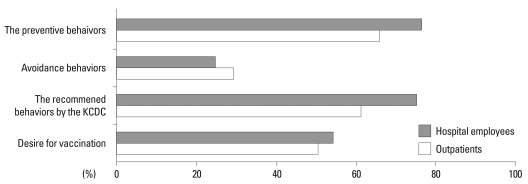

Concerning the performance of preventative behaviors, 674 of the hospital employees (76.6%) performed the preventative behaviors, that comprised avoidance behaviors (n = 218, 24.8%) and the KCDC-recommended preventative behaviors (n = 661, 75.1%). Four hundred seventy nine of the hospital employees (54.4%) desired vaccination. Of the outpatients, 631 (65.9%) performed the preventative behaviors. Among those, 586 (61.2%) performed the KCDC-recommended behaviors, while 280 (29.3%) performed avoidance behaviors. Four hundred and eighty-four of the outpatients (50.6%) desired vaccination (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Proportions of the preventive behaviors and desire of vaccination for pandemic influenza between hospital employees and outpatients. The preventive behaviors consisted of avoidance behaviors or the recommended behaviors by the KCDC. KCDC, Korea Center of Disease Control and Prevention.

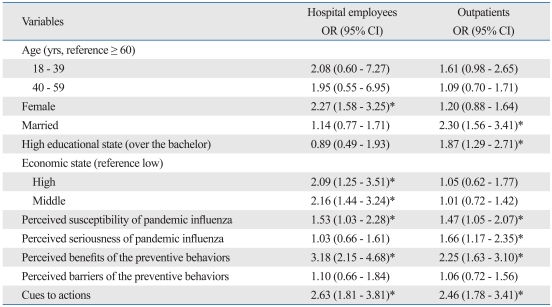

In all hospital employees, the statistically significant factors related to the preventive behaviors included female gender [odds ratio (OR) 2.27, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.58-3.25], high and middle economic state (OR 2.09, CI 1.25-3.51 and OR 2.16, CI 1.44-3.24, respectively), perceived susceptibility of the pandemic influenza (OR 1.53, CI 1.03-2.28), perceived benefits of the preventive behaviors (OR 3.18, CI 2.15-4.68), and cues to actions (OR 2.63, CI 1.81-3.81). Among the outpatients, the statistically significant factors related to the preventive behaviors included marital state (OR 2.30, CI 1.56-3.41), advanced education (OR 1.87, CI 1.29-2.71), perception of susceptibility (OR 1.47, CI 1.05-2.07), recognition of seriousness of health threat (OR 1.66, CI 1.17-2.35), perception of benefits (OR 2.25, CI 1.63-3.10), and cues to action (OR 2.46, CI 1.78-3.41) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factors Related to Performance of Preventive Behaviors for Pandemic Influenza in Hospital Employees and Outpatients

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

p value was calculated by multivariable logistic regression.

*p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Since the first case of H1N1 pandemic influenza was reported from Mexico in April 2009,7 many countries have sought to curb the global transmission of the disease. In Korea, the government and the media have disseminated information concerning preventative behaviors.2 We had expected that this information campaign would have instilled a high degree of knowledge regarding H1N1 and preventative actions.

However, a half of both hospital employees and outpatients felt that they were easily infected by pandemic influenza, while less than half thought that pandemic influenza was a serious disease. At the time of the WHO phase 5 alert, only 20-30% of respondents perceived that pandemic influenza was serious.3,4 These figures could have reflected the lower incidence of the disease, relative to the United States, which experienced many more cases in September, 2009.2 This speculation is difficult to assess, since no studies have been published concerning the public perception of H1N1 in the US at that time. Prior to the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), a similarly low recognition of the threat posed by the disease was reported.8 Efforts to bolster public awareness and recognition of infectious health threats prior to an actual outbreak are needed.

More 70% of hospital employee participants regarded the preventive behaviors, like avoidance behaviors or the recommended behaviors by KCDC, as beneficial and performed these behaviors in preventing pandemic influenza. But among outpatients, less 70% perceived and performed them. The higher perception and performance in hospital employees may have reflected the occupational environment, especially that of health care workers, in which the risk of contracting influenza and health care workers may be transmission vectors of influenza unfortunately.9 Therefore, health care workers must have an effort on the prevention of influenza by basic infection control options including hand washing and use of protective equipment (e.g., N95 mask or gloves).10,11 The outpatient data differed from those of a previous study in the UK, which reported that more than half of the general population perceived the efficacy of hand washing, while only 37% performed the recommended behaviors.2 This difference may reflect a selection bias due to the convenience sampling adopted. Another bias was the study period. In this study, the WHO alert pandemic influenza alert was phase 6, in contrast to phase 5 in the UK study.1,3 Death had occurred in Korea before this study period, but had not occurred in the UK before that study.2,3 Vaccination for pandemic influenza was not an option during the period of the Korean study. Thus, preventative measures were the only option.

Participants who were female or in a higher economic state among the hospital employees, and who were married or highly educated among the outpatients, were likely to adopt the preventive behaviors. This difference may be due to the heterogeneity between the two groups. Participants among the hospital employees were mostly young, female, highly educated, and in a middle-to-high economic state, perhaps reflecting the proportion of nurses and doctors in the respondent sample. Compared to the present results from the outpatients, previous studies conducted with the general population reported that females, those who are more elderly, or the parents of young children tend to be more receptive to the benefits of options such as hand washing, while a variable level of education may lead to variable avoidance behaviors.3,8

HBM components, especially the perception of personal susceptibility, seriousness, benefits of preventative behaviors, and cues to action were related to preventive behaviors. The HBM was a useful model in the interpretation of community response to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).8 In the UK study, preventive actions related to perceptions that pandemic influenza is severe, that the risk of acquisition is high, and that hand washing was associated with perceived efficacy,4 echo the present results.

Half of hospital employees and outpatients desired vaccination for H1N1 pandemic influenza. In the general population, the vaccination rate of seasonal influenza vaccination is approximately 50%.12 This rate was low in health care workers, in contrast to our results, and high in those afflicted with chronic diseases such as asthma,13,14 but lack of data prevented us from assessing the vaccination rate in those at high risk.

Our study has some limitations. First, the generalization of the results is limited due to non-random sampling. To generalize beyond this study, further studies will be required. Second, the spread of the pandemic influenza is now underway, so these results may change, especially the desire for vaccination. Third, hospital employees consisted of doctors, nurses, technicians and hospital administrators, so the results may reflect the views of the predominant group. In addition, we did not estimate the high risk group for pandemic influenza in outpatient participants.

In summary, more than 75% of hospital employees and 65% of outpatients perceived the benefits of preventive behaviors for H1N1 pandemic influenza and performed them. Factors related to the preventive behaviors were gender, economic state in hospital employees, and marital and educational state in outpatients. All components of the HBM except perception of barriers were associated with the preventive behaviors in both groups. We encourage performance of preventive behaviors continuously, considering these factors.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. [accessed on October 2009]. Available at http://www.euro.who.int/influenza/AH1N1/20090611_11.

- 2.Korea Center of Disease Control and Prevention. [access on October 2009]. Available at http://cdc.go.kr/

- 3.Rubin GJ, Amlôt R, Page L, Wessely S. Public perceptions, anxiety, and behaviour change in relation to the swine flu outbreak: cross sectional telephone survey. BMJ. 2009;339:b2651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seale H, McLaws ML, Heywood AE, Ward KF, Lowbridge CP, Van D, et al. The community's attitude towards swine flu and pandemic influenza. Med J Aust. 2009;191:267–269. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mckenzie JF, Neifer BL, Smeltzer JL. Theories and models commonly used for health promotion intervention. Boston: Pearson education INC; 2005. Planning, Implementing and Evaluating health promotion program; pp. 156–158. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moon JS. A study of instrument development for health belief of Korean adults [dissertation] Seoul: Yonsei Univ; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. [access on October 2009]. Available at http://www.euro.who.int/influenza/NewsEventsb.

- 8.Lau JT, Yang X, Tsui H, Kim JH. Monitoring community responses to the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: from day 10 to day 62. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:864–870. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.11.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichol KL, Hauge M. Influenza vaccination of health care workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1997;18:189–194. doi: 10.1086/647585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jefferson T, Foxlee R, Del Mar C, Dooley L, Ferroni E, Hewak B, et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory virues: systematic review. BMJ. 2008;336:77–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39393.510347.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sansom GW. Emergency department personal protective equipment requirements following out-of-hospital chemical biological or radiological events in Australasia. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:86–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.00927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mok E, Yeung SH, Chan MF. Prevalence of influenza vaccination and correlates of intention to be vaccinated among Hong Kong Chinese. Public Health Nurs. 2006;23:506–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hollmeyer HG, Hayden F, Poland G, Buchholz U. Influenza vaccination of health care workers in hospitals--a review of studies on attitudes and predictors. Vaccine. 2009;27:3935–3944. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyn-Cook R, Halm EA, Wisnivesky JP. Determinants of adherence to influenza vaccination among inner-city adults with persistent asthma. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16:229–235. doi: 10.3132/pcrj.2007.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]