Abstract

Background

The complexity of the wheat genome has resulted from waves of retrotransposable element insertions. Gene deletions and disruptions generated by the fast replacement of repetitive elements in wheat have resulted in disruption of colinearity at a micro (sub-megabase) level among the cereals. In view of genomic changes that are possible within a given time span, conservation of genes between species tends to imply an important functional or regional constraint that does not permit a change in genomic structure. The ctg1034 contig completed in this paper was initially studied because it was assigned to the Sr2 resistance locus region, but detailed mapping studies subsequently assigned it to the long arm of 3B and revealed its unusual features.

Results

BAC shotgun sequencing of the hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum cv. Chinese Spring) genome has been used to assemble a group of 15 wheat BACs from the chromosome 3B physical map FPC contig ctg1034 into a 783,553 bp genomic sequence. This ctg1034 sequence was annotated for biological features such as genes and transposable elements. A three-gene island was identified among >80% repetitive DNA sequence. Using bioinformatics analysis there were no observable similarity in their gene functions. The ctg1034 gene island also displayed complete conservation of gene order and orientation with syntenic gene islands found in publicly available genome sequences of Brachypodium distachyon, Oryza sativa, Sorghum bicolor and Zea mays, even though the intergenic space and introns were divergent.

Conclusion

We propose that ctg1034 is located within the heterochromatic C-band region of deletion bin 3BL7 based on the identification of heterochromatic tandem repeats and presence of significant matches to chromodomain-containing gypsy LTR retrotransposable elements. We also speculate that this location, among other highly repetitive sequences, may account for the relative stability in gene order and orientation within the gene island.

Sequence data from this article have been deposited with the GenBank Data Libraries under accession no. GQ422824

Background

Wheat (Triticum aestivum) is one of the major food crops in the world, providing 20% of the total food calories and protein in human nutrition [1] but its large genome size (~16000 Mb) and complexity (~80% repetitive sequences) has hindered genome sequencing studies [2]. To date, the largest sequenced, assembled and annotated genomic sequence from BAC clones from Triticeae genomes is 439 kb [3]. The recent publication of the physical map of the largest wheat chromosome 3B [4], along with other mapping projects initiated within the international wheat genome sequencing consortium (IWGSC), has established a platform for more extensive sequencing studies.

The high complexity of the wheat genome produced by such factors as retrotransposable element insertion [5] and polyploidy, has complicated comparisons between the genomes of closely related species. Gene deletions and disruptions generated by the fast replacement of repetitive elements in wheat [6-8], have resulted in loss of colinearity at a micro (sub-megabase) level [9-12]. In view of genomic changes that are possible within a given time span, conservation of gene structure, order and orientation between species tends to imply an important functional or regional constraint that does not permit a change in genomic structure [13]. The ctg1034 sequence characterized in the present study is a good example of such high conservation of structure.

The availability of finished, whole genome sequences for rice (Oryza sativa) [14] and Sorghum bicolor [15], as well as extensive sequencing of the maize (Zea mays; http://www.maizesequence.org) and Brachypodium (Brachypodium distachyon http://www.brachypodium.org) genomes, has provided a basis for a detailed analysis of colinearity. Due to a lack of whole genome sequence data for wheat, micro-colinearity has been confirmed on individual sequenced genetic loci of agronomically important genes [16,17] but little work has been carried out to identify any detailed relationships in regions of low gene density.

Gene islands exist in grass genomes [18-21] and gene-densities of over one gene every 20 kb have been reported [7,22]. On wheat chromosome 3B, Charles et al. [5] carried out random BAC sequencing to identify transposable element distribution and annotated the very few active genes within distal regions of the long-arm of the chromosome. Only one gene island (containing two active genes) was identified out of the 10 annotated BAC clones.

In this study we report on the sequencing of a group of 15 BACs located within FPC ctg1034 from the hexaploid wheat chromosome 3B physical map [4], and their assembly into a 783,553 bp genomic sequence. This large genomic sequence is among the first reported for the long arm of chromosome 3B and is also one of the largest and most complete genomic sequences described for wheat. The 783,553 bp genomic sequence was initially studied because it was assigned to the Sr2 resistance locus region, however detailed mapping studies subsequently assigned it to the long arm of 3B and revealed its unusual features. Annotation of ctg1034 through bioinformatics analysis identified a conserved gene island containing three genes of different gene function. Comparative analysis with five other cereal genomes revealed the highly conserved nature of the gene island despite no apparent co-expression or other shared functional attributes being identified.

Results

Ctg1034 sequence assembly and chromosome 3B mapping

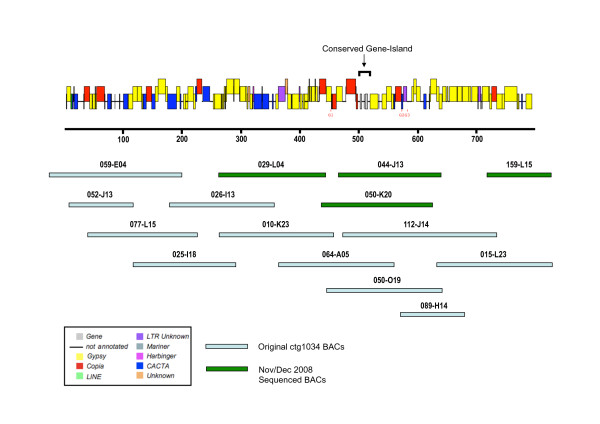

The sequencing of chromosome 3B-ctg1034 from Triticum aestivum cv. Chinese Spring was initially carried out using a BAC-by-BAC shotgun method at a 6× sequencing coverage. Twelve BACs (026-I13, 025-I18, 077-L15, 059-E04, 052-J13, 010-K23, 111-P10, 064-A05, 050-O19, 112-J14, 089-H14 and 015-L23) were originally selected from the chromosome 3B physical map generated by FPC mapping [4] (Figure 1). Gap closure was carried out by identifying sequence read pairs and designing primers to extend the genomic sequence. A second set of four BAC clones (029-L04, 044-J13, 159-L15 and 050-K20) was sequenced at 10× coverage in an attempt to close all remaining genomic sequence gaps (Figure 1). The sixteen wheat BACs were assembled using the Phred/Phrap sequence assembly package [23]. BAC contigs were ordered and assembled into a scaffold sequence by using target site duplications (TSDs) located at the ends of transposable elements (T. Wicker et al manuscript in preparation). TSDs associated with a particular transposable element allowed this element to be annotated even if nested insertions had occurred within it to complicate its internal structure.

Figure 1.

Genome sequence annotation of ctg1034 showing the wheat BAC clones that were used in the assembly of the genomic sequence. The retrotransposable elements have been color coded as indicated in the insert.

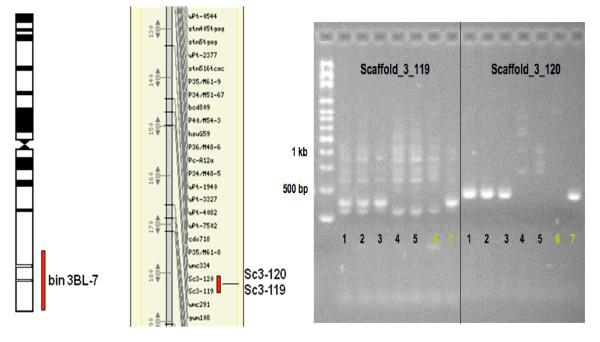

The BAC contigs sequenced in this study were initially linked to BACs located in the region of the Sr2 locus (Mago et al. in preparation) of chromosome 3BS and the contig was of interest because of the identification of a defensin gene within the gene island. However, when no overlap could be found within assembled contigs, markers were tested to re-examine the chromosome location of the BACs. Two insertion site based polymorphism (ISBP) markers [7,24,25] were identified in the sequence and used to screen the Cranbrook × Halberd mapping population [26] to find the chromosomal location of ctg1034 on chromosome 3B. Figure 2(A) shows the genetic mapping analysis results on the Cranbrook × Halberd mapping population which confirmed earlier indications from studies using a French (INRA) mapping population that contig 1034 was co-located with molecular markers previously assigned to bin 3BL-7, on the long arm of 3B. Confirmation of the location in bin 3BL7 is provided in Figure 2B using the same ISBP markers used for the genetic mapping. The ISBP Sc3-119 marker primers (predicted PCR band size of 158 bp) showed multiple PCR bands with the band of the expected size missing from lanes 4 and 5. For ISBP Sc3-120, the PCR showed a single band of the expected size (190 bp) and this band was missing in lanes 4 and 5. Since lanes 3 and 4 are deletion lines 3BL10 and 3BL7 the analysis indicated that the locus containing the ISBP is located on 3BL7 [4].

Figure 2.

Location of ctg1034. A (left panel). Genetic mapping using two ISBP markers, Sc3-119 and Sc3-120 on the Cranbrook × Halberd population [26] demonstrated a co-location with markers assigned to bin3BL-7 on the long arm location on 3B [72]. The genetic map shows a small part of the map (complete map, Cran*Hal 3B Feb09, is available at http://ccg.murdoch.edu.au/cmap/ccg-live/). B (right panel). The bin 3BL-7 region of chromosome 3B is characterized by the SSRs Xgwm299, Xgwm2152, Xgwm547, Xgwm247, Xgwm340, Xgwm181, Xfwm4, Xcfa2170, Xbarc84, Xpsr170, XksuG62 [72] and the two ISBP markers (Sc3-119 and Sc3-120) could be assigned to this deletion bin. Lane 1-8 on the electrophoresis gel on the left-hand panel of the figure indicates the analysis of Sc3-119 and Sc3-120 with the deletion bins of chromosome 3B (lane 1: 3BS-8, lane 2: 3BS-9, lane 3: 3BS-1, lane 4: 3BL-10, lane 5: 3BL-7, lane 6: Halberd and lane 7: Cranbrook).

Transposable element annotation of ctg1034

Transposable elements (TEs) were annotated in this study using BLASTN and BLASTX [27] sequence homology searches against the non-redundant nucleotide (e-value < 1e-30) and protein (e-value < 1e-10) sets of the Triticeae repetitive element (TREP) database. Alignments to TEs located within ctg1034 were confirmed using the DOTTER dot-matrix program [28] and were used to identify target site duplications (TSDs) at either end of the element. Table 1 lists the TE families that are distributed within ctg1034 and their sequence proportions compared to the rest of the assembled contig.

Table 1.

Transposable element Annotation of Chromosome 3B ctg1034

| Class | Order | Family | Code | Elements | Complete TSD | Nested | Length (bp) | % TEs | % Contig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I (Retrotransposable elements) |

|||||||||

| LINE | Unknown | RIX | 1 | 1 | 2962 | 0.46% | 0.38% | ||

| LTR | Copia | RLC | 9 | 9 | 1 | 93966 | 14.66% | 11.99% | |

| Gypsy | RLG | 55 | 39 | 19 | 401485 | 62.64% | 51.24% | ||

| Unknown | RLX | 6 | 3 | 2 | 29915 | 4.67% | 3.82% | ||

| Total | 71 | 51 | 23 | 528328 | 82.42% | 67.43% | |||

| Class II (DNA Transposons) | TIR | CACTA | DTC | 9 | 5 | 5 | 100864 | 15.74% | 12.87% |

| Harbinger | DTH | 1 | 1838 | 0.29% | 0.23% | ||||

| Mutator | DTM | 1 | 802 | 0.13% | 0.10% | ||||

| Tc1- mariner | DTT | 1 | 693 | 0.11% | 0.09% | ||||

| Unknown | DXX | 1 | 730 | 0.11% | 0.09% | ||||

| Total | 13 | 5 | 5 | 104927 | 16.37% | 13.39% | |||

| Unknown | XXX | 2 | 7733 | 1.21% | 0.99% | ||||

| Total Transposable elements | 86 | 56 | 28 | 640988 | 81.81% |

Overall, TEs made up 81.8% of the entire ctg1034 chromosome 3B sequence. The repetitive element content was dominated by retrotransposable elements (class I TEs, 82.42% of all TEs and 67.43% of the entire contig), considered to transpose through the action of a RNA intermediate. This was compared to the DNA transposons (class II), which comprised only 16.37% of all TEs (13.39% of the total contig). The gypsy family of long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposable elements were by far the most abundant type of class I-TE, with 71 out of the 86 transposons found (51 of which were complete with intact TSDs) and occupying more than half the total sequence of ctg1034 (51.24%).

Two gypsy elements, Romani located at 698,865 - 709732 bp and Latidu located at 510,556 - 523623 bp in ctg1034, were also found to contain significant matches to chromodomains, which are located in the C-terminal region of the integrase (IN) protein domain of the gypsy internal polyprotein (gag-pol) domain [29]. A profile HMM [30] constructed using consensus sequences of reverse transcriptase (RT) and IN domains in [31] was used to identify potential chromodomain matches (e-values of 5.7e-307 and 1.5e-303 for Romani and Latidu respectively). Chromodomains were originally identified in the centromeric heterochromatin proteins of Drosophila [32,33] and have been argued to target heterochromatin by recognizing histone modifications [31]. The internal regions of both the Romani and Latidu LTR gypsy elements were also searched using BLASTX against the characterised internal domains of the gypsy mobile genetic element database (GyDB) [34]. Both elements contained significant matches (evalue of 1e-149) to the integrase domain of the O.sativa LTR gypsy element Retrosat-2.

The CACTA DNA transposons and copia LTR families were also well represented with 12.87% and 11.99% of the total ctg1034 sequence respectively. The CACTA DNA transposons had a high proportion of elements (5 out of the 9 elements found) that contained nested insertions. Gypsy LTR retrotransposons had a slightly lower proportion of nested elements (19 out of 55). The copia LTR elements were found to be the most intact with only one element containing a nested insertion and all identified to be complete with TSDs.

Tandem repeats considered to be located within heterochromatic regions in Triticeae genomes were also assayed to identify matches to ctg1034. Two matches were genome specific' Aegilops squarrosa repetitive DNA sequence (GenBank accession: D30736) [35] and the other being an Aegilops tauschii so-called centromeric-specific tandem repeat from clone 6C6-3 (Genbank accession: AY249982) [36]. The well-studied D30736 repeat [35] is from the Afa1 family of tandem repeats (based on the restriction enzyme site) and is made up of 240 bp units, only one of which was located in the ctg1034 sequence between 72,048 and 72,279 bp (89% nucleotide identity over 233 bp). The AY249982 repeat was almost a perfect match (92% nucleotide identity over 1018 bp) between 40,882 and 41,898 bp. Both these representatives of tandem repeat families were located within TEs, with the D30736 repetitive DNA sequence found within the CACTA DNA transposon Conan and the AY249982 tandem repeat found within the gypsy LTR retrotransposon Cereba.

Gene content annotation of ctg1034

The 783,553 bp ctg1034 sequence was masked for repetitive elements with the repeat masking program Repeatmasker http://www.repeatmasker.org run using the triticeae repetitive element (TREP) database http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/ITMI/Repeats. The masked sequence was then passed through gene prediction programs FGENESH http://linux1.softberry.com/berry.phtml and GlimmerHMM [37]. Predicted gene models from both programs were screened against the Michigan State University (MSU) O. sativa annotation project's http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/ protein database and NCBI non-redundant amino-acid database using BLASTP to identify non-redundant gene matches. A database of 11,902 full-length wheat cDNA sequences from the KOMUGI Wheat Genetic Resource http://www.shigen.nig.ac.jp/wheat/komugi/ was also screened to identify any direct matches to wheat cDNAs. All annotated genes followed the standard GT-AG eukaryotic intron splice site model.

Four gene models of significant homology to characterised protein matches in NCBI non-redundant amino acid and MSU rice protein database were all found within a 16 kb window between 491,000-507,000 bp of the ctg1034 contig. The first gene model found at the very beginning of the 16 kb region was identified to be a fragment (28% coverage) of the MSU rice gene hit, LOC_Os05 g35160 (Clathrin assembly protein) with no significant wheat EST or cDNA match and was not considered further. The other three gene models were annotated as gene-coding sequences and all had hits to the NCBI non-redundant protein database. All three genes were annotated using BLASTX alignments to the MSU rice protein annotations [38] and their intron-exon structure was confirmed using both a wheat subset of Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs) from NCBI and rice full-length cDNA information [39]. The overall gene-density of the ctg1034 sequence was 1 gene per 261,184 bp.

The first of the three genes, named TaEP1, was identified to be 2,489 bp in length and encoded a predicted protein of 551 amino acids over 2 exons (Table 2). The gene has a high similarity at the amino acid level (85% identity) to an expressed protein in rice (LOC_Os01 g68830) as well as a catalytic domain-containing protein in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; At3 g07210) (49% identity). The gene was supported by multiple wheat full-length ESTs (CJ799192, BE500656, BG263254, BQ170023) all with a greater than 95% nucleotide identity. The second gene (TaCRP1) was quite small at only 436 bp in length and encoded a predicted protein of 118 amino acids over 2 exons (Table 2). The gene was well supported by multiple full-length ESTs (CA636856, BQ806045, CA702257 and CA707955), which all had a greater than 95% nucleotide identity. The predicted protein of the gene was found to have homology (60% aminoacid identity)to an expressed protein in rice (LOC_Os01 g68840), which appears in the MSU rice community annotation as a small, cysteine-rich protein named CRP6[40]. In previous work involving legumes [41], small cysteine rich peptides (CRPs) were classified as different classes of defensins, proteins that are active in conferring resistance to bacteria, fungi and viruses. The Cx(2)-CxCCx(6)-Cx(4)-CCx(4)-Cx(9)-Cx(6)-CxCx(2) (Figure 3b) arrangement of the cysteine domain in TaCRP1corresponds to the ma ternally expressed gene (MEG) family.

Table 2.

Gene and EST analysis of the ctg1034'gene -island' genes

| Gene | Position | Size (bp) | Number of exons | Number of amino acids | Wheat EST (>80% coverage) | E-value | Gene coverage | Wheat Unigene set |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaEP1 | 493556-496044 | 2489 | 2 | 551 | CJ799192 (667 bp) | 0.0 | 27% (over 1 exon) | Ta.11404 |

| TaCRP1 | 500300-500735 | 436 | 2 | 118 | BQ806045 (623 bp) | 0.0 | 73% (over 2 exons) | Ta.14062 |

| TaZFN1 | 502241-506766 | 4526 | 7 | 435 | CK209603 (1147 bp) | 7e-144 | 21% (over 5 exons) | Ta.11131 |

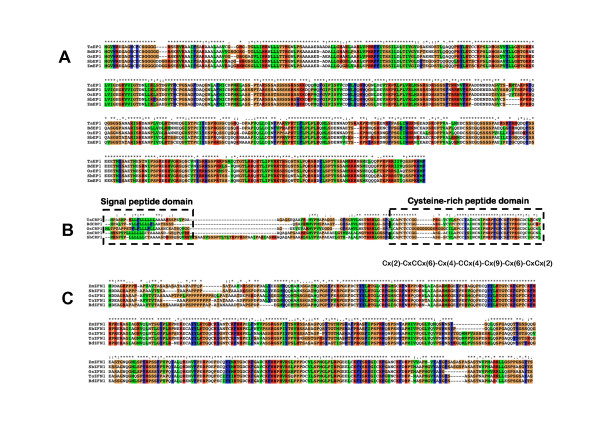

Figure 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of three collinear gene island genes (TaEP1 (A), TaCRP1 (B) and TaZFN1(C)) using CLUSTALX [78]. Each of the wheat, Brachypodium and maize genes were annotated in this study, while the S. bicolor (v1.0 annotations from http://www.phytozome.net/sorghum) and rice annotations [38]. Annotated on the TaCRP1 alignment is the signal peptide and cysteine-rich domain structures outlined in [40]. Colors found on the figure are determined by the CLUSTAL color scheme, which is based on amino acid types.

The last gene matched the NCBI non-redundant amino acid database was annotated as a zinc finger protein (TaZFN1). This gene was 4,525 bp, has a 7-exon gene structure and encodes a predicted protein of 430 amino acids (Table 2). The gene was shown to have high homology (82% identity) to the rice zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein ZFN-like 2 (Q5JLB5) and well supported by wheat ESTs (Table 2) and a full-length wheat cDNA taken from the KOMUGI Wheat Genetic Resources Resource http://www.shigen.nig.ac.jp/wheat/komugi/. TaZFN1 was the only one of the four identified gene models that had a match to a full-length wheat cDNA; the cDNA match to the coding sequence of TaZFN1 was almost 100%, with only 2 base differences.

The NCBI Unigene EST profiles http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/unigene of each of the genes were compared in Table 3, showing the expression of each of the genes in wheat, barley (Hordeum vulgare) and rice tissue-specific EST pools. There was a low-level of transcription of the EP1 gene and no tissue specificity could be inferred from the data across all species. While there was a low-level of transcription found from the EST data for the CRP1 gene, there was clear seed-tissue specificity across all species relative to the expression in leaf and root tissues. The ZFN1 gene displayed much higher transcription levels than the previous two genes but like EP1 showed no tissue-specificity could be inferred.

Table 3.

Wheat and Rice UniGene EST expression profiles of the three genes located within the ctg1034 gene island.

| UniGene Accession | Seed* | Leaf* | Root* | Stem* | Callus* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP1 | ||||||

| Wheat | Ta.11404 | 2 (21) | 0 | 2 (11) | 0 | 0 |

| EST pool sizes | 161877 | 57503 | 166795 | 93580 | 10594 | |

| Barley** | Hv.27853 | 0 | 1 (17) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EST pool sizes | 88535 | 111884 | 32853 | 65681 | 16046 | |

| Rice | Os.42759 | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 3 (23) | 1 (6) |

| EST pool sizes | 32419 | 171897 | 68247 | 126907 | 164917 | |

| CRP1 | ||||||

| Wheat | Ta.14062 | 4 (24) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Barley | Hv.19960 | 1 (11) | 0 | 0 | 1 (15) | 1 (62) |

| Rice | Os.65102 | 3 (92) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (48) |

| ZFN1 | ||||||

| Wheat | Ta.11131 | 34 (210) | 8 (139) | 6 (35) | 11 (117) | 1 (94) |

| Barley | Hv.8311 | 4 (45) | 11 (98) | 2 (60) | 2 (30) | 0 |

| Rice | Os.19086 | 3 (92) | 5 (29) | 0 | 3 (23) | 12 (2) |

*The number of tissue-specific ESTs is shown and the extrapolated transcripts per million (TPM) are shown in brackets

**Barley EST profiles are also shown on the basis of BLASTN homology searches against the NCBI EST dataset.

Comparative analysis using the gene-island-coding sequences from cereal genomes

The three genes found as a small cluster or island within the wheat ctg1034 region of chromosome 3B were used to search against the rice (O. sativa ssp. japonica) and Sorghum bicolor genome sequences and each genome was found to be syntenic over the region, showing both conserved gene order and orientation. The rice MSU version 6 annotation of chromosome 1 between 39,898,000 to 40,011,000 bp (Table 2) in the rice genome was used along with the Sorghum Sbi1.4 annotation models (from MIPS/PASA on v1.0 assembly preliminary Genome-scan annotation of assembly sbi0 http://www.phytozome.net) from chromosome 3 of Sorghum bicolor from between 71,051,000 and 71,068,000 bp (17 kb region).

The three genes from ctg1034 were also searched against the Brachypodium (Brachypodium distachyon) line Bd21 and maize (Zea mays cv B73) genome sequences using BLASTN and the top hits of all three were once again found to have conserved gene order and orientation. The equivalent of the wheat 16 kb region in the draft Brachypodium super13 scaffold sequence (1311-1327 kb) contained the conserved colinear genes and was annotated using the same protocol used to annotate the ctg1034 wheat genome sequence. The three genes were named BdEP1, BdCRP1 and BdZFN1 based on their rice protein matches in the MSU version 6 annotations (same as the wheat gene annotation, Table 4). A small genomic sequence gap within the draft sequence (4× sequence coverage) located inside exon 6 and intron 5 of BdZFN1 was filled on request to the Brachypodium genome-sequencing project (Bevan, M., pers. comm.) and reduced the size of the syntenic gene island sequence to 14 kb. A syntenic region containing the TaEP1, TaCRP1 and TaZFN1 genes in maize was located within the ctg131 FPC contig on maize chromosome 3. The maize genomic BAC clone containing all three genes (AC217295.3) was accessed from the maize genome sequence project website http://maizesequence.org/ and were annotated for all genes (Additional file 1) based on alignments to Sorghum bicolor gene annotations http://www.phytozome.net/sorghum with intron-exon structures confirmed using NCBI maize ESTs. The three genes were named ZmEP1, ZmCRP1 and ZmZFN1. Transposable elements were annotated using BLASTN against the TIGR Zea repeat database [42](Figure S2 in Additional file 2).

Table 4.

Characteristics of three wheat genes identified to be syntenic and colinear genome sequences to the rice, Brachypodium and S. bicolor genome sequences.

| Rice Genome | S. bicolor Genome | Maize Genome | Brachypodium Genome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Description | Gene Match | Chr1 position (strand) | Gene Match | Chr3 position (strand) | Gene Match* | AC217295.3 Position (strand) | Gene Match* | Super_13 position (strand) |

| TaEP1 | Expressed Protein | LOC_Os01 g68830 | 39991137-39993669 (+) | Sb03 g043790 | 71051976-71055103 (+) | ZmEP1 | 65318-67814 (+) | BdEP1 | 1312106-1314592 (+) |

| TaCRP1 | Expressed Protein | LOC_Os01 g68840 | 39997846-39997379(-) | Sb03 g043800 | 71059536-71060101(-) | ZmCRP1 | 117899-118353 (-) | BdCRP1 | 1317872-1318293 (-) |

| TaZFN1 | Putative zinc finger CCCH type domain- containing protein |

LOC_Os01 g68860 | 40009733-40005685 (-) | Sb03 g043810 | 71062164-71067135 (-) | ZmZFN1 | 119558-125029 (-) | BdZFN1 | 1319767-1324280 (-) |

*denotes the Brachypodium and maize genes that were annotated along with wheat in this study.

TaEP1 showed the highest level of amino-acid conservation (Figure 3a) among the EP1 genes in the cereal genomes. The highest similarity was with Brachypodium BdEP1 (88% identity at the amino acid level), followed by rice LOC_Os01 g68830 (85%), S. bicolor Sb03 g043790 and maize ZmEP1 (both 81% identity). TaEP1 also had 49% amino acid identity to a peptidase protein AT3G07210 in Arabidopsis. The Brachypodium BdEP1 also had a good conservation of non-coding nucleotide sequence within the intron of TaEP1. The intron sequence of BdEP1 was 70% identical over 836 nucleotides with 85% sequence coverage compared to the rice comparison, which had only 16% coverage over the 826 nucleotides. There was a small region of 110 bp near the start of the intron that did not show any homology. The intron sequence of maize ZmEP1 compared to S. bicolor Sb03 g043790 was also highly conserved (78% identical over 821 nucleotides with 99% coverage).

The large 7-exon TaZFN1 gene, much like TaEP1, showed significant homology to its Brachypodium orthologous sequence. The amino acid sequences of both genes showed 89% identity over 387 amino acids, with only a small section located within the first exon lacking homology. Both S. bicolor (403 amino acids) and rice (443 amino acids) showed 82% identity compared to TaZFN1, with maize showing the least similarity at amino acid level (77% over 429 amino acids). The amino acids from the first exon (1-80 amino acids in Figure 3c) seemed to contain the most sequence divergence when compared to the rest of the genome sequences. As was found in TaEP1, there was a significant conservation of the non-coding sequence between TaZFN1 and BdZFN1, especially in introns 3, 5 and 6 which all have a nucleotide sequence coverage of >62%. The ZFN1 gene sequence between maize and S. bicolor was also well conserved (84% identity over 4915 nucleotides) except for two small inserts contained within the fifth intron of ZmZFN1, one insert of 1,166 bp and another of 118 bp. The larger 1,166 bp insert contained two small transposable elements CASINE (63 bp) and F524 (91 bp) classified as SINE elements from the non-LTR retrotransposable element group.

By comparison, the TaCRP1 showed the least amount of homology across the genomes when analysed at the amino acid level (Figure 3b) relative to TaEP1 and TaZFN1. Once again, Brachypodium had the highest amino acid homology (85% identity), followed by rice (66%), S. bicolor (62%) and maize (60%). The low amino acid identity was due to insertions within the rice, maize and S. bicolor amino acid sequences. S. bicolorSb03 g043800 had a 33 amino acid insertion located just after the signal peptide and before the cysteine domain. It is also the only CRP1 sequence out of the five syntenic gene copies that had only one exon (no intron). The cysteine domain located in the last 50 amino acids of the gene was conserved in all genomes (~75% identity). The only significant difference in the cysteine-rich domain across all genomes was a six amino acid insertion (all glycine residues) within the rice LOC_Os01 g68840 sequence. Exon 1 in all sequences that contained multiple exons showed little nucleotide and amino acid sequence homology and exon 2 was the only region found to have significant sequence conservation. Exon 2 contained the coding sequence of the cysteine-rich domain. No significant intron sequence similarity could be identified across the genomes.

The syntenic gene island region across five genomes

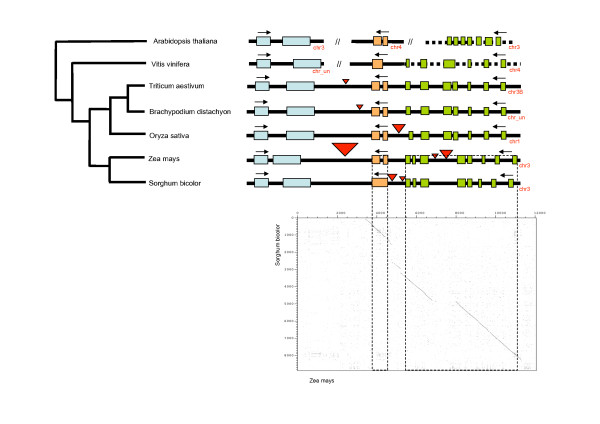

The ctg1034 14 kb gene island was analysed across the available genomic sequences including Arabidopsis genome sequence [43], the grapevine (Vitis vinifera) genome sequence [44] and the wheat, Brachypodium, S. bicolor, rice and maize genome sequences. The 14 kb, three-gene region containing TaEP1, TaCRP1 and TaZFN1 did not show any conservation of colinearity in the Arabidopsis genome sequence. Chromosome 4 of the grapevine genome did have homologs of TaCRP1 and TaZFN1 located within a 17 kb window (in the same relative orientation as in wheat) but also contained a small (65 predicted amino acid) gene found in between. This small gene coding for a 65 aa protein has no rice or Arabidopsis BLASTX hit and could possibly be within a transposable element.

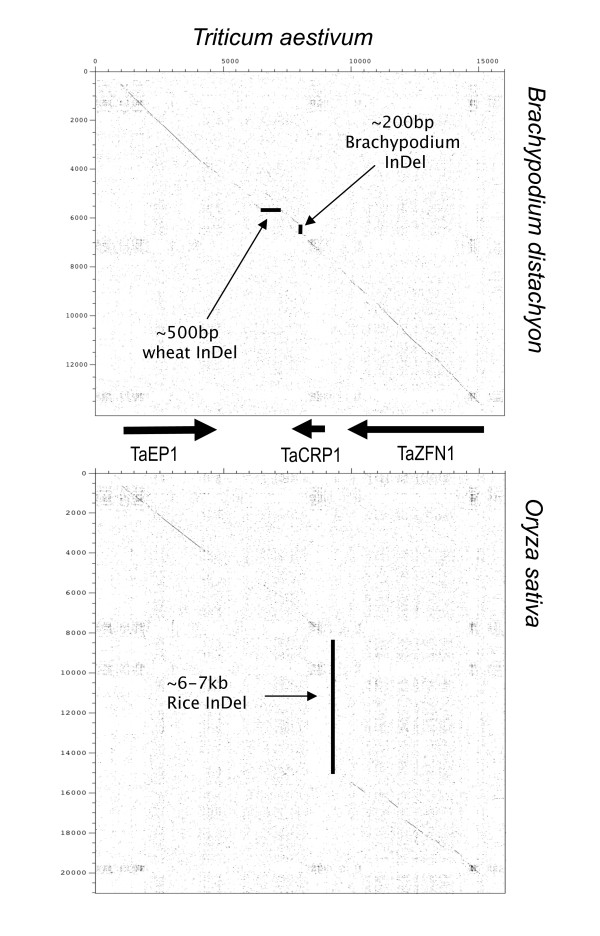

There are large size differences of the gene-island regions between wheat (16 kb) and both maize (63 kb) and rice (22 kb) resulted from an insertion-deletion event (InDel) in both cases. Comparing the genome sequences of rice against the wheat gene island region shows a 6-7 kb sequence variation (InDel) between the OsCRP1 and OsZFN1 genes (Figure 4). The proposed InDel within the rice genome contains a hypothetical protein annotation LOC_Os01 g68850 and contained many MITE and DNA transposons found in the TIGR Oryza Repeat Database v3.1 (repeat_212948; 230577; 212949; 205504; 216962) including a MULE or Mutator-like element (BPM2_1011). The LOC_Os01 g68850 open-reading frame was identified using FGENESH and contained a high amount of repetitive elements. Furthermore, the match to sequences in the EST databases of rice indicated the largest region of significant homology (94% identity to rice EST CK043734) was only 208 bp and thus it seems unlikely to be an active entity.

Figure 4.

Pair-wise sequence comparison of wheat and Brachypodium gene island regions against the wheat and rice gene island regions. The wheat genes (TaEP1, TaCRP1 and TaZFN1) are annotated on the figure and the arrows indicate the proposed insertion-deletion (InDel) events resulting in sequence movement between the species. Wheat contained a ~500 bp InDel, while Brachypodium and rice showed ~200 bp and ~6-7 kb InDels respectively.

Overall, in five of the genome sequences used in this study, there was a highly conserved gene sequence, order and orientation, when compared to the wheat ctg1034 gene island (Figure 5), even though the size of the region differed considerably; greatest in the maize genome (63 kb), followed by rice (22 kb), S. bicolor (17 kb) and Brachypodium (14 kb) (Figure 5). The 4× draft Brachypodium super13 scaffold sequence showed the highest nucleotide coverage (53% coverage), followed by rice (31%), S. bicolor (29%) and maize (23%) when each sequence was compared to the 16 kb gene island wheat genomic sequence using NCBI BLAST 2 Sequences (BLASTN) [45]. A detailed analysis of the differences in length in this region between the genomes analysed (Figure 4 and the red triangles in Figure 5) is provided in the Additional file 2.

Figure 5.

A gene island sequence summary figure next to a deduced evolutionary tree from analysed genome sequences homologous to the wheat chromosome 3BL ctg1034 gene island. The red triangles indicate proposed insertion-deletion (InDel) events identified in this study. An example of a dot plot indicating the occurrence of InDels is shown beneath the pair-wise sequence comparison between the maize and S. bicolor. The analysis demonstrates the location of the InDels between the start of the cysteine-rich peptide gene (CRP1) to the end of the Zinc finger protein (ZFN1) region. A detailed analysis of the differences in length in this region between the genomes analysed (red triangles) is provided in the Additional file 2.

Discussion

In this study a group of twelve hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum cv Chinese Spring) BAC clones from chromosome 3B were assembled into a 783,553 bp genomic sequence (called ctg1034) that was then analysed for biological features.

Diverse gene functions in a conserved gene-island

The three gene-coding sequences on ctg1034 (TaEP1, TaCRP1 and TaZFN1), located within a 14 kb sequence, all show different sequence characteristics and a range of expression patterns and functions based on rice annotations. TaEP1 is highly conserved in plant genomes (even in Arabidopsis) but does not show any distinct characterised function in sequenced genomes such as S. bicolor and rice. TaCRP1, on the other hand, is a small cysteine-rich protein, a protein from a diverse, well characterised protein family that is involved in pathogen defence [40]. TaZFN1 was like TaCRP1, a well-characterised protein from a large family of transcription factors that have been extensively studied. Furthermore multiple full-length cDNA sequences of TaZFN1 in rice indicate alternative splicing forms of the gene product (LOC_Os01 g68860.1, LOC_Os01 g68860.2 and LOC_Os01 g68860.3) exist. EST expression profiles from 3 did not provide any clear indication of co-expression of the three genes; TaZFN1 was striking in its relatively high levels of expression in a range of tissue compared to TaEP1 and TaCRP1. This is consistent with the genes being involved in independent pathways within cells.

Gene island structure is maintained over the evolution of plant genomes despite the occurrence of InDels

Conservation of colinearity between grass species has been reported extensively at a micro-level [17,46] but even in colinear regions, gene order and orientation may not be conserved [6,9,17,46-48]. The conserved gene-islands described between wheat and other major crop species such as rice [11], have been limited because of the use of EST and single BAC sequences (unlike the large assembled sequences created in this study), with the associated lack resolution making it difficult to reach definitive conclusions about the level of conservation. While conserved gene islands at gene-rich orthologous loci have been shown, small genetic rearrangements were found to dramatically change gene order in maize and S. bicolor [48] and a mosaic of rearrangements between rice and wheat were also reported, with the conservation of gene orientation only limited to local duplications in one species [49].

The gene island provides a contrast to the concepts developing from mammalian genome studies that repeat sequence regions may be hot-spots for structural change in gene regions [50]. While the relative order and orientation of the genes within the ctg1034 gene island has been maintained, the intergenic region was not immune to changes during the course of its evolution. Figure 5 shows a summary evolutionary tree deduced from colinearity and sequence similarity seen in this study over the ctg1034 gene island. This evolutionary tree is consistent with taxonomic relationships [51].

Despite the large amount of repetitive elements that surround the island, only the rice and maize genome (Figure 5 and Additional file 2) sequences showed post-divergence TE insertions. An insert within maize is not unusual, as [52] has shown that even maize inbred lines can show intra-specific variation in genetic colinearity. High sequence diversity in maize can be caused by TEs such as Helitrons [52-54]. The 6-7 kb rice insertion mostly contained miniature inverted TEs (MITEs), known to insert into and be associated with gene-containing regions [23,55,56] and [36] suggested that these small TEs might also have a role in modification of expression in neighbouring genes. Another TE found within the insert was a MULE transposon. So called Pack-MULEs are extremely common in the rice genome [57] and have been implicated in the evolution of genes within higher plant genomes through their ability to capture and carry fragments of genomic DNA to create new open reading frames.

Gene island location on chromosome 3BL

The gene density in this study was identified to be quite low at 1 gene per 260 kb. In contrast, gene densities in Triticeae genomes (most notably barley and wheat) have been reported to be much higher (1 gene per 9 kb [58] and 1 gene per 4-5 kb [19]), possibly reflecting the initial targeting of important agronomic genes in distal regions of chromosomes [59] rather than a random representation of the genome sequence. Random wheat BAC sequencing [7] indicated that even in gene-rich regions of wheat, the gene density is considerably lower than previously thought (approximately 1 gene per 75 kb). Genetic mapping studies showed Sc3-119 and Sc3-120 ISBP markers from ctg1034 were located within the terminal deletion bin 3BL-7 on chromosome 3B (Figure 2), a deletion bin known to contain two major C-bands [59]. Previous cytogenetic studies of the wheat chromosomes suggested a large variation of gene-density over the entire length of chromosomes [60,61] and it is feasible that particularly low gene densities occur within C band regions. The low gene density found in this study is more consistent with studies in Triticeae genomes of more proximal regions of chromosome arms (1 gene per 518 kb [62]) and regions of low recombination (1 gene per 175 kb [63]).

The two representatives of tandem repeat families located within the first 75 kb of the ctg1034 sequence also indicate a relationship to heterochromatin, with one (AY249982) being previously identified to be a D-genome centromeric heterochromatin tandem repeat sequence [35,36]. The presence of a representative of this D-genome specific repeat in the chromosome 3B sequence suggest specific amplification of the sequence family must have occurred in the D genome even though single copy representatives were located elsewhere. The presence of representatives of sequences normally located as tandem arrays in heterochromatin and the presence of high gypsy LTR content support our proposal that this ctg1034 genomic sequence is located within a C-banding region in deletion bin 7 of chromosome 3BL.

The highly repetitive element content in ctg1034 (81.81%) was not unusual in wheat sequences, as studies have shown repetitive element contents of greater than 70% [21,56,64], however the high content of the gypsy-like LTR retrotransposon is significant in this study (>50% of the entire contig). A previously sequenced wheat BAC clone from the same chromosome 3BL-7 deletion bin [5] also found a similar high proportion of gypsy-like LTR-retrotransposons. In the present study, chromodomains were shown to be located within the internal polyprotein domain of two gypsy-LTR retrotransposons, and are thus potentially key components defining the condensed nature of heterochromatin [29,65]. One of the potential chromodomains (Latidu LTR gypsy retrotransposon) was located immediately adjacent to the gene island in ctg1034.

The unusual properties of heterochromatin that would contribute to the unique conservation of both the gene order and relative gene orientation found in this study include: (a) the low levels of recombination and gene activity associated with heterochromatin [33,66]; (b) the high level of transcript processing by the RNAi machinery that mediates chromatin structure [67-71]. These properties could contribute to the relative isolation of the gene island from the normal processes that lead to genome rearrangements.

Conclusion

BAC shotgun sequencing of the FPC physical map contig ctg1034 from the genome of chromosome 3B has provided the largest assembly of a wheat genome region to date (783,553 bp). Annotation and comparative analysis with four other plant genomes of (B. distachyon, O. sativa, S. bicolor and Zea mays) identified an island of three genes showing complete conservation of gene order and orientation. This conservation could not be readily accounted for by shared functions between the genes and it is proposed that ctg1034 is located within a heterochromatic C-band region of deletion bin 3BL7 based on the identification of representatives of heterochromatin tandem repeats and presence of significant matches to chromodomain-containing gypsy LTR retrotransposable elements. We speculate that this location, among other highly repetitive sequences, may account for the relative stability of the gene island through insulating the gene island from normal recombination processes.

Methods

Mapping of selected BAC clones

Selected clones were mapped to chromosome 3B using insertion site based polymorphism (ISBP) markers [7,23]. Two ISBPs (Sc3-119 and Sc3-120) from ctg1034 were located on the long arm of chromosome 3B using standard deletion stocks of wheat [2]. The Sc3-119 primer 5'-TCCAAGACGTTTCTTCCACC-3' and 5'-GAGGTGACGTGGCATCATTA-3' generated a 158 bp product and was located at 510,455 bp within the ctg1034 sequence. The second ISBP used, Sc3-120 with primer '5-GCCCCTGGCTTGTATTATGA-3' and 5'-TCAGCTGAAGGGTCGTTTTT-3' giving a 190 bp specific fragment located at 523,485 bp. The PCRs carried out on genome DNA from the standard 3B deletion stocks and the 162 double haploid lines from the cross Cranbook × Halberd followed standard reaction conditions [25,72].

BAC shotgun sequencing

E. coli-freed DNA from BAC clones was extracted with Qiagen Large-Construct Kit (QIAGEN, Cat. No. 20021) and mechanically sheared with HydroShear as recommended by ABI applied biosystems https://products.appliedbiosystems.com/ab/en/US/adirect/ab?cmd=catNavigate2&catID = 604432, generating a concentrated smear ~3-5 kb in length. The sheared fragments were blunt ended with mung bean nuclease and dephosphorylated with Shrimp Alkaline Phosphatase (SAP). The short fragments were then tailed with A by PCR using standard procedures.. Fragments ranging from 3-5 kb in size were isolated and ligated into a pCR4-TOPO vector and transformed into TOP10 electrocompetent cells (Invitrogen, Cat. No. K4580-01). The clones were sequenced from both directions with T3 and T7 primers using BigDye3.1 termination chemistry and run on an ABI Prism 3730 XL capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif., USA). Base calling, quality assessment and sequence assembly were done using the PHRED/PHRAP software package [23]. Gaps were filled by primer walking using adding dGTP mix and DMSO in the sequencing reaction system.

Sequence Analysis and Annotation

Repetitive DNA analysis was carried out using Repeatmasker (Smit et al. 1996-2004, http://www.repeatmasker.org) and BLAST local alignment searching [26] against the Triticeae repetitive element (TREP) database http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/ITMI/Repeats/ and the gypsy mobile elements database (GyDB) [34]. Open reading frames were identified by the use of FGENESH http://www.softberry.com/, GENSCAN [73] and GlimmerHMM [37]. Sequence homology searching was carried out by BLAST programs with a cut-off E-value of 1e-30 for nucleotide sequences and 1e-10 for amino acid sequences. All EST matches to genes were required to have >80% coverage over the EST sequence. Protein domains were identified by searching the Pfam protein family database [74], as well as the conserved domains database (CDD) at NCBI [75]. InterProScan [76] was run against the InterPro protein domain database [77], which also includes a signal peptide and Trans-membrane search. Pair-wise sequence comparisons were carried out using DOTTER [27] and multiple sequence comparisons were carried out using the CLUSTALX [78]. The hidden markov model search program HMMer [30] was also used. Graphical display of the sequence map was produced with WICKERsoft™ scripts.

Comparative Sequence analysis

Genome sequence annotations used in this study include release 5 of the TIGR rice pseudomolecules [38], the 4× draft genome sequence of B.distachyon http://www.brachypodium.org/, the 2a.50 release of the Maize (Z. mays) genome sequence http://www.maizesequence.org and release 1 of the S. bicolor genome http://www.phytozome.net/sorghum. Multipipmaker [79] and Multidotter [80] were used for nucleotide sequence comparisons. CLUSTALX was used to compare amino acid sequences and Multidotter, Mauve [81] and ACT [82] was used to compare multiple genome sequences at one time.

Authors' contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

JB, TW, MB, RAs: Assembly of the genome sequence and annotation of genes and TEs

EP, CF: Cloning and assembly of BACs from chromosome 3B

XK, JZ: Sequencing of BAC clones

WM: Mapping of ISBPs to wheat genetic map

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1. Gene Annotation of Maize Chromosome 3 BAC AC217295.3.

Supplementary INDELs file. Detailed of the InDels shown as red triangles in Figures 4 and 5 of the main manuscript.

Contributor Information

James Breen, Email: jbreen@ccg.murdoch.edu.au.

Thomas Wicker, Email: wicker@botinst.unizh.ch.

Xiuying Kong, Email: xykong@mail.caas.net.cn.

Juncheng Zhang, Email: jczhang2008@163.com.

Wujun Ma, Email: W.Ma@murdoch.edu.au.

Etienne Paux, Email: etienne.paux@clermont.inra.fr.

Catherine Feuillet, Email: catherine.feuillet@clermont.inra.fr.

Rudi Appels, Email: rappels@ccg.murdoch.edu.au.

Matthew Bellgard, Email: mbellgard@ccg.murdoch.edu.au.

Acknowledgements

The BAC clones used in this study derived from the Minimal Tiling Path of ctg1034 in the chromosome 3B physical map of hexaploid wheat project within the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC). The authors thank Fred Choulet provided the Perl scripts for identifying ISBP markers. Thanks to Yasunari Ogihara(Kihara Institute for Biological Research and Graduate School of Integrated Science, Yokohama City University, Japan) for advanced access to full-length cDNAs for wheat and Junhong Ma (SABC, Murdoch University, Australia) for laboratory work. The authors appreciated the help provided by Prof M Bevan to fill-in a gap in the Brachypodium genome sequence. Finally, thanks to David Dunn, Paula Moolhuijzen and all technical staff at the CCG for Bioinformatics support. Molecular Plant Breeding Co-operative Research Centre (MPBCRC) and Murdoch University generously supported funding for this work.

References

- Gupta PK, Mir RR, Mohan A, Kumar J. Wheat genomics: present status and future prospects. International journal of plant genomics. p. 896451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gill BS, Appels R, Botha-Oberholster AM, Buell CR, Bennetzen JL, Chalhoub B, Chumley F, Dvorak J, Iwanaga M, Keller B. et al. A workshop report on wheat genome sequencing: International Genome Research on Wheat Consortium. Genetics. 2004;168:1087–1096. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.034769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker T, Zimmermann W, Perovic D, Paterson AH, Ganal M, Graner A, Stein N. A detailed look at 7 million years of genome evolution in a 439 kb contiguous sequence at the barley Hv-eIF4E locus: recombination, rearrangements and repeats. Plant J. 2005;41:184–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paux E, Sourdille P, Salse J, Saintenac C, Choulet F, Leroy P, Korol A, Michalak M, Kianian S, Spielmeyer W. et al. A physical map of the 1-gigabase bread wheat chromosome 3B. Science. 2008;322:101–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1161847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles M, Belcram H, Just J, Huneau C, Viollet A, Couloux A, Segurens B, Carter M, Huteau V, Coriton O. et al. Dynamics and differential proliferation of transposable elements during the evolution of the B and A genomes of wheat. Genetics. 2008;180:1071–1086. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.092304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubcovsky J, Ramakrishna W, SanMiguel PJ, Busso CS, Yan L, Shiloff BA, Bennetzen JL. Comparative sequence analysis of colinear barley and rice bacterial artificial chromosomes. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1342–1353. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.3.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos KM, Ma J, Pontaroli AC, Pratt LH, Bennetzen JL. Analysis and mapping of randomly chosen bacterial artificial chromosome clones from hexaploid bread wheat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:19243–19248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509473102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubcovsky J, Dvorak J. Genome plasticity a key factor in the success of polyploid wheat under domestication. Science. 2007;316:1862–1866. doi: 10.1126/science.1143986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appels R, Francki M, Chibbar R. Advances in cereal functional genomics. Funct Integr Genomics. 2003;3:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s10142-002-0073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Loukoianov A, Tranquilli G, Helguera M, Fahima T, Dubcovsky J. Positional cloning of the wheat vernalization gene VRN1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6263–6268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937399100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrells ME, La Rota M, Bermudez-Kandianis CE, Greene RA, Kantety R, Munkvold JD, Miftahudin, Mahmoud A, Ma X, Gustafson PJ. et al. Comparative DNA sequence analysis of wheat and rice genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:1818–1827. doi: 10.1101/gr.1113003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francki M, Carter M, Ryan K, Hunter A, Bellgard M, Appels R. Comparative organization of wheat homoeologous group 3S and 7L using wheat-rice synteny and identification of potential markers for genes controlling xanthophyll content in wheat. Funct Integr Genomics. 2004;4:118–130. doi: 10.1007/s10142-004-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd AE, Orengo CA, Thornton JM. Evolution of function in protein superfamilies, from a structural perspective. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:1113–1143. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Rice Genome Sequencing Project. The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature. 2005;436:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nature03895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Bruggmann R, Dubchak I, Grimwood J, Gundlach H, Haberer G, Hellsten U, Mitros T, Poliakov A. et al. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature. 2009;457:551–556. doi: 10.1038/nature07723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantret N, Cenci A, Sabot F, Anderson OD, Dubcovsky J. Sequencing of the Triticum monococcum hardness locus reveals good microcolinearity with rice. Mol Genet Genomics. 2004;271:377–386. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-0991-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faris JD, Zhang Z, Fellers JP, Gill BS. Micro-colinearity between rice, Brachypodium, and Triticum monococcum at the wheat domestication locus Q. Funct Integr Genomics. 2008;8:149–164. doi: 10.1007/s10142-008-0073-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel P, Tikhonov A, Jin YK, Motchoulskaia N, Zakharov D, Melake-Berhan A, Springer PS, Edwards KJ, Lee M, Avramova Z. et al. Nested retrotransposons in the intergenic regions of the maize genome. Science. 1996;274:765–768. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuillet C, Keller B. High gene density is conserved at syntenic loci of small and large grass genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8265–8270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonov AP, SanMiguel PJ, Nakajima Y, Gorenstein NM, Bennetzen JL, Avramova Z. Colinearity and its exceptions in orthologous adh regions of maize and sorghum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7409–7414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker T, Stein N, Albar L, Feuillet C, Schlagenhauf E, Keller B. Analysis of a contiguous 211 kb sequence in diploid wheat (Triticum monococcum L.) reveals multiple mechanisms of genome evolution. Plant J. 2001;26:307–316. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell KS, Langridge P, Powell W. Comparative sequence analysis of the region harboring the hardness locus in barley and its colinear region in rice. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:3177–3190. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.044081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 1998;8:186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paux E, Roger D, Badaeva E, Gay G, Bernard M, Sourdille P, Feuillet C. Characterizing the composition and evolution of homoeologous genomes in hexaploid wheat through BAC-end sequencing on chromosome 3B. Plant J. 2006;48:463–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos J, Paux E, Kofler R, Havrankova M, Kopecky D, Suchankova P, Safar J, Simkova H, Town CD, Lelley T. et al. A first survey of the rye (Secale cereale) genome composition through BAC end sequencing of the short arm of chromosome 1R. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmensiek A, Eckermann PJ, Verbyla AP, Appels R, Sutherland MW, Daggard GE. Curation of wheat maps to improve map accuracy and QTL detection. Aus J Agric Res. 2005;56:1347–1354. doi: 10.1071/AR05126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnhammer EL, Durbin R. A dot-matrix program with dynamic threshold control suited for genomic DNA and protein sequence analysis. Gene. 1995;167:GC1–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novikova O. Chromodomains and LTR retrotransposons in plants. Commun Integr Biol. 2009;2:158–162. doi: 10.4161/cib.7702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy SR. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:755–763. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novikova O, Mayorov V, Smyshlyaev G, Fursov M, Adkison L, Pisarenko O, Blinov A. Novel clades of chromodomain-containing Gypsy LTR retrotransposons from mosses (Bryophyta) Plant J. 2008;56:562–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paro R, Hogness DS. The Polycomb protein shares a homologous domain with a heterochromatin-associated protein of Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:263–267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgin SC. Heterochromatin and gene regulation in Drosophila. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:193–202. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(96)80050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloréns C, Futami R, Bezemer D, Moya A. The Gypsy Database (GyDB) of mobile genetic elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D38–46. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaki K, Tsujimoto H, Isono K, Sasakuma T. Molecular characterization of a tandem repeat, Afa family, and its distribution among Triticeae. Genome. 1995;38:479–486. doi: 10.1139/g95-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Arbuckle J, Wessler SR. Recent, extensive, and preferential insertion of members of the miniature inverted-repeat transposable element family Heartbreaker into genic regions of maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1160–1165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majoros WH, Pertea M, Salzberg SL. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2878–2879. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang S, Zhu W, Hamilton J, Lin H, Campbell M, Childs K, Thibaud-Nissen F, Malek RL, Lee Y, Zheng L. et al. The TIGR Rice Genome Annotation Resource: improvements and new features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D883–887. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi S, Satoh K, Nagata T, Kawagashira N, Doi K, Kishimoto N, Yazaki J, Ishikawa M. Rice Full-Length cDNA Consortium, National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences Rice Full-Length cDNA Project Team et al. Collection, mapping, and annotation of over 28,000 cDNA clones from japonica rice. Science. 2003;301:376–379. doi: 10.1126/science.1081288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein KA, Moskal WA, Wu HC, Underwood BA, Graham MA, Town CD, VandenBosch KA. Small cysteine-rich peptides resembling antimicrobial peptides have been under-predicted in plants. Plant J. 2007;51:262–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham MA, Silverstein KA, Cannon SB, VandenBosch KA. Computational identification and characterization of novel genes from legumes. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1179–1197. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.037531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang S, Buell CR. The TIGR Plant Repeat Databases: a collective resource for the identification of repetitive sequences in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D360–363. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000;408:796–815. doi: 10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillon O, Aury JM, Noel B, Policriti A, Clepet C, Casagrande A, Choisne N, Aubourg S, Vitulo N, Jubin C. et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature. 2007;449:463–467. doi: 10.1038/nature06148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusova TA, Madden TL. BLAST 2 Sequences, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:247–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantret N, Salse J, Sabot F, Bellec A, Laubin B, Dubois I, Dossat C, Sourdille P, Joudrier P, Gautier MF. et al. Contrasted microcolinearity and gene evolution within a homoeologous region of wheat and barley species. J Mol Evol. 2008;66:138–150. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SA, Huang L, Herbel MN, Gill BS, Brown-Guedira G, Fellers JP. Structural variation and evolution of a defense-gene cluster in natural populations of Aegilops tauschii. Theor Appl Genet. 2006;112:618–626. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen JL, Ramakrishna W. Numerous small rearrangements of gene content, order and orientation differentiate grass genomes. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;48(5-6):821–7. doi: 10.1023/A:1014841515249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyot R, Yahiaoui N, Feuillet C, Keller B. In silico comparative analysis reveals a mosaic conservation of genes within a novel colinear region in wheat chromosome 1AS and rice chromosome 5S. Funct Integr Genomics. 2004;4(1):47–58. doi: 10.1007/s10142-004-0103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mefford H, Sharp A, Baker C, Itsara A, Jiang Z, Buysse K, Huang S, Maloney V, Crolla J, Baralle D, Collins A. et al. Recurrent Rearrangements of Chromosome 1q21.1 and Variable Pediatric Phenotypes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(16):1685–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg EA. Evolutionary history of the grasses. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1198–1205. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.3.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J, Li Y, Messing J, Dooner HK. Gene movement by Helitron transposons contributes to the haplotype variability of maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9068–9073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502923102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal SK, Hannah LC. Plant genomes: massive changes of the maize genome are caused by Helitrons. Heredity. 2005;95:421–422. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckler ES, Gaut BS, McMullen MD. Molecular and functional diversity of maize. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker T, Guyot R, Yahiaoui N, Keller B. CACTA transposons in Triticeae. A diverse family of high-copy repetitive elements. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:52–63. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.015743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabot F, Guyot R, Wicker T, Chantret N, Laubin B, Chalhoub B, Leroy P, Sourdille P, Bernard M. Updating of transposable element annotations from large wheat genomic sequences reveals diverse activities and gene associations. Mol Genet Genomics. 2005;274:119–130. doi: 10.1007/s00438-005-0012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Bao Z, Zhang X, Eddy SR, Wessler SR. Pack-MULE transposable elements mediate gene evolution in plants. Nature. 2004;431:569–573. doi: 10.1038/nature02953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SA, Huang L, Gill BS, Fellers JP. Analysis of 106 kb of contiguous DNA sequence from the D genome of wheat reveals high gene density and a complex arrangement of genes related to disease resistance. Genome. 2002;45:963–972. doi: 10.1139/g02-049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L, Echalier B, Friebe B, Gill BS. Molecular characterization of a set of wheat deletion stocks for use in chromosome bin mapping of ESTs. Funct Integr Genomics. 2003;3:39–55. doi: 10.1007/s10142-002-0063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill KS, Gill BS, Endo TR, Taylor T. Identification and high-density mapping of gene-rich regions in chromosome group 1 of wheat. Genetics. 1996;144:1883–1891. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faris JD, Haen KM, Gill BS. Saturation mapping of a gene-rich recombination hot spot region in wheat. Genetics. 2000;154:823–835. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.2.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsuda T, Pourkheirandish M, He C, Azhaguvel P, Kanamori H, Perovic D, Stein N, Graner A, Wicker T, Tagiri A. et al. Six-rowed barley originated from a mutation in a homeodomain-leucine zipper I-class homeobox gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1424–1429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608580104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak J, Akhunov ED, Akhunov AR, Deal KR, Luo MC. Molecular characterization of a diagnostic DNA marker for domesticated tetraploid wheat provides evidence for gene flow from wild tetraploid wheat to hexaploid wheat. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:1386–1396. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel PJ, Ramakrishna W, Bennetzen JL, Busso CS, Dubcovsky J. Transposable elements, genes and recombination in a 215-kb contig from wheat chromosome 5A(m) Funct Integr Genomics. 2002;2:70–80. doi: 10.1007/s10142-002-0056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Hou Y, Ebina H, Levin HL, Voytas DF. Chromodomains direct integration of retrotransposons to heterochromatin. Genome Res. 2008;18:359–369. doi: 10.1101/gr.7146408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künzel G, Korzun L, Meister A. Cytologically integrated physical restriction fragment length polymorphism maps for the barley genome based on translocation breakpoints. Genetics. 2000;154:397–412. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.1.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler VL, Alleman M. Paramutation: Epigenetic Instructions Passed Across Generations. Genetics. 2008;178(4):1839–4. doi: 10.1093/genetics/178.4.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe T, Schramke V, Hamilton GL, White S, Teng G, Martienssen RA, Allshire RC. RNA interference is required for normal centromere function in fission yeast. Chromosome Res. 2003;11:137–146. doi: 10.1023/A:1022815931524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May BP, Lippman ZB, Fang Y, Spector DL, Martienssen RA. Differential regulation of strand-specific transcripts from Arabidopsis centromeric satellite repeats. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin VV, Sigova A, Li C, Seitz H, Gvozdev V, Zamore PD. A distinct small RNA pathway silences selfish genetic elements in the germline. Science. 2006;313:320–324. doi: 10.1126/science.1129333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Vasiljeva L, Rando OJ, Zhelkovsky A, Moore C, Buratowski S. Distinct pathways for snoRNA and mRNA termination. Mol Cell. 2006;24:723–734. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sourdille P, Singh S, Cadalen T, Brown-Guedira GL, Gay G, Qi L, Gill BS, Dufour P, Murigneux A, Bernard M. Microsatellite-based deletion bin system for the establishment of genetic-physical map relationships in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Funct Integr Genomics. 2004;4:12–25. doi: 10.1007/s10142-004-0106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge C, Karlin S. Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J Mol Biol. 1997;268(1):78–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, Tate J, Mistry J, Coggill PC, Sammut SJ, Hotz HR, Ceric G, Forslund K, Eddy SR, Sonnhammer EL. et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D281–288. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hao L, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD. et al. CDD: a conserved domain database for interactive domain family analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D237–240. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N, Apweiler R, Lopez R. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W116–120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apweiler R, Attwood TK, Bairoch A, Bateman A, Birney E, Biswas M, Bucher P, Cerutti L, Corpet F, Croning MD. et al. The InterPro database, an integrated documentation resource for protein families, domains and functional sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:37–40. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Current protocols in bioinformatics/editoral board, Andreas D Baxevanis [et al] 2002;Chapter 2(Unit 2.3) doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0203s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Elnitski L, Li M, Weirauch M, Riemer C, Smit A, Program NCS, Green ED, Hardison RC, Miller W. MultiPipMaker and supporting tools: Alignments and analysis of multiple genomic DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3518–3524. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki Y, Macgregor A, Smith C, Hunter A, Bellgard M. Multidotter: Dot-Matrix Program for Multiple Sequences. The 2005 International Conference on Mathematics and Engineering Techniques in Medicine and Biological Sciences (METMBS'05), Las Vegas, USA. 2005.

- Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver TJ, Rutherford KM, Berriman M, Rajandream MA, Barrell BG, Parkhill J. ACT: the Artemis Comparison Tool. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3422–3423. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1. Gene Annotation of Maize Chromosome 3 BAC AC217295.3.

Supplementary INDELs file. Detailed of the InDels shown as red triangles in Figures 4 and 5 of the main manuscript.