Abstract

AIMS

Infliximab, an anti-TNF biologic agent, is currently indicated and reimbursed for rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn's disease (both adult and paediatric), ulcerative colitis, psoriatic arthritis and plaque psoriasis. Development of national and international guidelines for rheumatology, gastroenterology and dermatology, was mostly based on clinical studies and expert opinion. The aim of this study was to compare available guidelines and local protocols for rheumatology, dermatology and gastroenterology, regarding dosage of infliximab, synergy of infliximab with concomitant medication and monitoring of vital signs during infliximab administration, for achieving optimal care.

METHODS

Current international, national and local guidelines on the use of infliximab were reviewed and compared, differences and shortcomings were identified, and optimal treatment schedules discussed during a meeting (July 2008) of clinical experts and researchers from three departments of a Dutch university hospital.

RESULTS

Recommended dosages of infliximab are not equal for different indications. Loss of response to infliximab is a common problem encountered within the three medical specialties, but indications for adjustments in treatment schedules are lacking in all of the guidelines. Monitoring of vital signs (blood pressure, pulse, temperature) during infusion with infliximab is common practice and recommended by some guidelines. Routine measurement of vital signs is not of any value in predicting or recognizing acute infusion reactions, in our experience, and this is confirmed by literature on inflammatory bowel disease.

CONCLUSION

Different indications encompass different dosing schedules. National and internal guidelines do not provide advice regarding loss of response. Routine measurement of vital signs during infusion is not valuable in detecting acute infusion reactions and should only be performed in case of an acute infusion reaction. These topics need to be studied in future studies and covered in future guidelines.

Keywords: ankylosing spondylitis, guidelines, inflammatory bowel disease, infliximab, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study is the first study which compared current international, national and local guidelines from the medical specialties involved in the treatment with infliximab on the following topics: indication, dosage, synergy and monitoring of vital signs.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Infliximab is an effective treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn's disease (both adult and paediatric), ulcerative colitis, psoriatic arthritis and plaque psoriasis and national and international guidelines have been developed for each indication.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and psoriasis are chronic inflammatory diseases. Although the exact causes of these diseases remain unknown, over the past two decades major advances have been made in understanding the inflammatory processes. It is likely that in each of these diseases the innate and adaptive immune system are activated, with subsequent production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, like tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [1–3]. Antibodies against TNF-α have been developed for the treatment of several chronic inflammatory diseases, including the monoclonal antibodies infliximab and adalimumab. Infliximab, a chimeric (partly human, partly murine) monoclonal antibody (biological), is the only intravenously administered anti-TNF antibody indicated and reimbursed for all of the following diseases: rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn's disease (both adult and paediatric), ulcerative colitis, psoriatic arthritis and plaque psoriasis.

National and international guidelines and consensus statements on the use of infliximab have been developed for each of the three medical specialties involved in treatment with infliximab (i.e. gastroenterology, rheumatology and dermatology) and reflect current use in clinical practice.

In many centres like ours, the care for patients receiving infliximab is combined for patients with auto-inflammatory disorders. This emphasizes the need for a combination of guidelines for the treatment with infliximab for patients with these disorders within the involved medical specialities.

Methods

This paper is the product of an expert panel meeting, held by the authors in July 2008.

The purposes of this meeting were as follows:

-

To identify similarities and differences within international, national and local guidelines and additional consensus statements from the medical specialties currently using infliximab as anti-TNF therapy, with regards to:

Indications for infliximab

Dosage for initial and maintenance therapy

Monitoring of vital signs during infusion with infliximab

Synergistic effects with concomitant medication use

To discuss the following topics: optimal dosage of infliximab, monitoring of vital signs and use of concomitant medication.

To discuss the optimal strategy in patients who have lost response to infliximab.

Members of the panel were selected, based on each member's clinical and/or research experience with use of infliximab, from the departments of rheumatology, gastroenterology and dermatology from our university hospital. Members from each medical field performed a literature search in their own discipline by searching the MEDLINE database until July 2008, using the keyword ‘infliximab’, limiting their search to practical guidelines and consensus statements. Additionally, the National Guideline Clearinghouse, a public resource for evidence-based clinical practice guidelines of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in the United States (http://www.guideline.gov) was searched on guidelines related to infliximab. In addition (local) Dutch guidelines from the medical specialties not accessible by MEDLINE but used in clinical practice were reviewed (for an overview of the reviewed guidelines and consensus statements see Table 1). Regarding these guidelines and consensus statements, we limited ourselves to the previously identified topics, namely indication, dosage, monitoring, synergy and loss of response (i.e. secondary inefficacy). Results were presented and discussed during the panel meeting. Additionally, hiatuses within guidelines and consensus statements were discussed.

Table 1.

Summary of reviewed consensus statements and guidelines regarding the use of infliximab

| Medical specialty | Study, year published (reference) | Paper | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastroenterology | Consensus statement | ||

| ECCO, 2006 [6] | European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: current management | Europe | |

| AGA, 2007 [4] | American Gastroenterological Association Consensus Development Conference on the use of biologics in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease | International | |

| Guidelines | |||

| Hommes et al., 2006 [7] | Guidelines for treatment with infliximab for Crohn's disease | The Netherlands | |

| Panaccione et al., 2004 [8] | Canadian Association of Gastroenterology clinical practice guidelines: The use of infliximab in Crohn's disease | Canada | |

| Rheumatology | Consensus statement | ||

| Furst et al., 2008 [9] | Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases | International | |

| Braun et al., 2006 [18] | First update of the international ASAS consensus statement for the use of anti-TNF agents in patients with ankylosing spondylitis | International | |

| NVR, 2004 [19] | Statement on the application of TNF-blockade in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis | The Netherlands | |

| CRA, 2003 [57] | Canadian rheumatology association consensus on the use of anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha directed therapies in the treatment of spondyloarthritis | Canada | |

| Guidelines | |||

| NICE, 2007 [11] | NICE technology appraisal guidance 130. Adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis | UK | |

| NVR, 2003 [12] | Guideline: Application of anti-TNF blockers in the treatment of rheumatoid arthtritis | The Netherlands | |

| FSR, 2007 [13] | Recommendations of the French Society for Rheumatology regarding TNFalpha antagonist therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis | France | |

| JCR, 2007 [14] | Update on the Japanese guidelines for the use of infliximab and etanercept in rheumatoid arthritis | Japan | |

| ACR, 2008 [17] | American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis | USA | |

| NICE, 2008 [23] | NICE technology appraisal guidance 143. Adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for ankylosing spondylitis | UK | |

| NICE, 2007 [24] | NICE technology appraisal guidance 104. Etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of adults with psoriatic arthritis | UK | |

| BSR, 2005 [16] | Update on the British Society for Rheumatology guidelines for prescribing TNFalpha blockers in adults with rheumatoid arthritis (update of previous guidelines of April 2001) | UK | |

| BSR, 2005 [21] | BSR guidelines for prescribing TNF-alpha blockers in adults with ankylosing spondylitis. Report of a working party of the British Society for Rheumatology | UK | |

| FSR, 2007 [22] | Recommendations of the French Society for Rheumatology regarding TNF alpha antagonist therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis or psoriatic arthritis: 2007 update | France | |

| Dermatology | Consensus statement | ||

| Reich et al., 2008 [25] | Recommendations for the long-term treatment of psoriasis with infliximab: A dermatology expert group consensus | Europe and Canada | |

| Sterry et al., 2004 [58] | Biological therapies in the systemic management of psoriasis: International Consensus Conference | International | |

| Guidelines | |||

| BAD, 2005 [26] | British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for use of biological interventions in psoriasis 2005 | UK | |

| NVDV, 2005 [27] | Guideline: Application of biologicals in the treatment of psoriasis | The Netherlands | |

| AAD, 2008 [36] | Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis – Section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. | USA | |

| NICE, 2008 [59] | Infliximab for the treatment of adults with psoriasis | UK | |

| AAD, 2008 [60] | Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis – Section 2. Psoriatic arthritis: Overview and guidelines of care for treatment with an emphasis on the biologics | USA |

AAD, American Academy of Dermatology; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; AGA, American Gastroenterological Association; BAD, British Association of Dermatologists; BSR, The British Society for Rheumatology; CRA, Canadian Rheumatology Association; ECCO, European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation; FSR, French Society of Rheumatology; JCR, Japan College of Rheumatology; NICE, National Institute for Clinical Excellence; NVDV, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Dermatologie en Verenologie; NVR, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Reumatologie.

Results

Indication

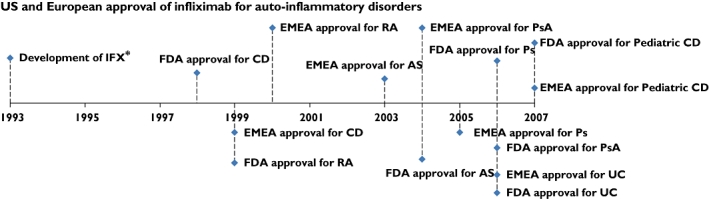

Infliximab was first approved for patients with Crohn's disease in 1998. Approval for other indications followed in the subsequent years (Figure 1). In general, patients not responding to conventional therapy and having a moderate to high level of disease activity are eligible for treatment with a biological like infliximab.

Figure 1.

Approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) of infliximab (IFX). AS, ankylosing spondylitis; CD, Crohn's disease; RA, rheumatoid arthritis, UC, ulcerative colitis; Ps, psoriasis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis. * Knight et al. [62]

Gastroenterology

Crohn's disease patients with extra-intestinal manifestations and fistulizing disease are especially eligible for treatment with infliximab [4, 5]. Both the international consensus statements of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and the European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) as well as national guidelines agree that treatment with infliximab is appropriate for patients with inflammatory bowel disease experiencing corticosteroid dependency, glucocorticoid and/or immunomodulative treatment refractoriness or active fistula associated with Crohn's disease [4, 6–8].

Rheumatology

In rheumatoid arthritis, the international consensus statement on biologicals for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, which is updated nearly every year, does not provide criteria on which patients should be treated with antibodies against TNF-α, like infliximab [9]. National guidelines, however, do provide such criteria. Patients should have failed on at least one (Swedish, French and Japanese guidelines) or two (British and Dutch guidelines) disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), including methotrexate in an adequate dosage and have a disease activity measured by the Disease Activity Score using 28 joint counts (DAS28) [10] of >5.1 (British guidelines) [11–16]. However, according to the Swedish guidelines no specific disease activity is required for starting with biologicals [15]. The consensus statement of The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommends starting with anti-TNF therapy like infliximab in cases with 1) high disease activity (DAS28 > 5.1) for 3–6 months, or 2) less than 3 months in combination with features of a poor prognosis (e.g. functional limitation, extra articular disease, rheumatoid factor positivity, bony erosions by radiography) or 3) moderate disease activity (DAS28 > 3.2 and <5.1) for >6 months and inadequate response to monotherapy with methotrexate in combination with features of poor prognosis [17].

Ankylosing spondylitis

The international consensus statement from Furst et al. does not provide criteria for treatment with infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis [9]. However, another international consensus statement from the ASsessment in Ankylosing Spondylitis (ASAS) working group [18], as well as a statement from the Dutch Society for Rheumatology [19] gives clear criteria on the use of infliximab in patients who fulfilled the modified New York criteria for the diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis [20], including active disease for >4 weeks,(Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) >4 (0–10) and an expert opinion (the expert should consider clinical features (history and examination), serum acute phase reactant levels and/or imaging results, such as radiographs demonstrating rapid progression or MRI indicating ongoing inflammation). Furthermore, all patients should have had adequate therapeutic trials of at least two NSAIDs, which is defined as:

Treatment for at least 3 months at maximum recommended or tolerated anti-inflammatory dose unless contraindicated

Treatment for <3 months where treatment was withdrawn because of intolerance, toxicity or contraindications

The guideline from the French Society for Rheumatology (FSR) is more strict regarding co-medication, stating that patients should have failed at least three NSAIDs used for 3 consecutive months while according to the guidelines from the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) there should be a failure of conventional treatment with two or more NSAIDs, each taken sequentially at maximum tolerated/recommended dosage for 4 weeks [21, 22]. Although the guidelines from the BSR recommend treatment with infliximab, the British guidelines from the National Health Service (NHS) state that infliximab is not recommended for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis [23].

Psoriatic arthritis

As for rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, the international consensus statement from Furst et al. does not provide criteria for treatment with infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis [9]. According to the NHS guidelines, patients with psoriatic arthritis are eligible for treatment with infliximab in case of peripheral arthritis with three or more tender joints and three or more swollen joints and the psoriatic arthritis has not responded to adequate trials of at least two standard DMARDs, administered either individually or in combination and the patient has been shown to be intolerant of, or have contraindications to, treatment with etanercept or has major difficulties with self administered injections [24]. The FSR guideline is more specific, indicating that the patient must have active and predominantly peripheral disease documented on two occasions at least 4 weeks apart, with both a tender joint count and a swollen joint count of ≥3 on a total of 76/78 joints and have an overall assessment of disease activity by the physician of ≥4 on a 10 point scale. Furthermore there should be persistent evidence of active disease after at least 4 months treatment with MTX in a dosage of ≥15 mg week−1, leflunomide ≥20 mg day−1, or sulfasalazine ≥2 g day−1[22].

Dermatology

Few guidelines and consensus statements on the use of infliximab exist for patients with plaque psoriasis. According to the international consensus statement by Reich et al. patients with psoriatic arthritis in association with skin symptoms or moderate to severe psoriasis who have failed two or more systemic therapies are eligible for treatment with infliximab [25]. Furthermore, patients with a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) of ≥20 or patients with an improvement of less than 50% on this scale with previous (non) biological treatment, were eligible for treatment with infliximab [25]. The guideline of the British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) states that patients should have severe disease, defined as a PASI of 10 or more (or a body surface area of 10% or greater where PASI is not applicable) and a Dermatology Life Quality Index >10. Secondly, patients should be unresponsive or intolerant to standard therapy [26]. In the Netherlands, patients are eligible for biological therapies if they have a PASI of ≥10, and have failed to respond to phototherapy, methotrexate and ciclosporin in the past, or have a contraindication to, or are intolerant of these treatments [27].

Dosage

The first randomized clinical trial with infliximab (at that time called cA2), in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, randomized patients over a single dose of 1 mg kg−1 bodyweight, 10 mg kg−1 bodyweight and placebo [28]. In this study, a dosage dependent response was observed. A subsequent study comparing the effect of multiple infusions with infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared 1 mg to 3 mg and 10 mg kg-1 bodyweight, showing the best results with the latter two [29]. Furthermore it was shown that the median duration of response to the lowest dosage (i.e. 1 mg kg−1 bodyweight) lasted 3 weeks, compared with 5 and 8 weeks with dosages of 3 and 10 mg kg−1 bodyweight, respectively [30].

Additional studies, performed in patients with Crohn's disease, compared a single dose of 5 mg, 10 mg or 20 mg kg−1 bodyweight, administered over a 2 h period. In this trial, patients receiving 5 mg kg−1 had the best response to infliximab [31]. An open-label trial in Crohn's disease patients, which was performed earlier, compared doses of 1 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg and 20 mg kg−1. The group receiving 1 mg kg−1 had a more transient response than the groups given the higher doses [32].

One of the first case reports of psoriasis patients treated with infliximab reported a significant response with 5 mg kg−1 bodyweight and the first randomized trial in patients with psoriasis showed significant responses to 5 mg kg−1 and 10 mg kg−1 bodyweight [33, 34].

Gastroenterology

With regard to dosing of infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease, as can be seen in Table 2, international and national consensus statement/guidelines recommend a dosage of 5 mg kg−1 body weight given in a 0-2-6-weeks induction regimen and followed by maintenance dosing every 8 weeks [4, 7]. The ECCO statement recommends the same dosage, since 5 mg kg−1 body weight has been shown effective in large placebo controlled trials [6, 35]. However, this consensus statement gives no information regarding any induction regimen. According to the AGA consensus, primary non response can be determined after two doses [4]. However, the Dutch guidelines recommend assessment of the treatment effect 8 weeks after the third infusion, when infliximab is combined with an immunosuppressant since immunosuppressants such as azathioprine and methotrexate only become effective after about 3 months [7]. When the response is attenuated in patients, dosage can be increased to 10 mg kg−1 body weight or the interval between infusions can be shortened up to 4 weeks [6, 7].

Table 2.

Statements from guidelines and consensus statements for different auto-inflammatory disorders on issues related to the use of infliximab: dosage regimen, induction therapy, loss of response, loss of response and the use of concomitant medication

| Indication | Study, year (reference) | Dosage (mg kg−1) | Induction therapy (weeks) | Maintenance intervals (in weeks) | Determination of (non) response* | Advice regarding loss of response in patients who initially responded to IFX | Recommended co-medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | Centocor, 2009 [61] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 8 | Active Crohn's disease: after two doses Fistulizing disease: after three doses | Some patients may regain response with dose escalation. | NA |

| ECCO, 2006 [6] | 5 | NA | 8 | NA | Most try increasing the dose to 10 mg kg−1 | AZA, MP or MTX | |

| AGA, 2007 [4] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 8 | After two doses | Patients who have attenuated response may be given - higher dose infusions up to 10 mg kg−1 at 8-week intervals, or - 5 mg kg−1 at shortened intervals as frequently as every 4 weeks. | Initiated in advance of biologic therapy | |

| Hommes et al., 2006 [7] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 8 | 4 weeks after the second infusion | Increase to 10 mg kg−1 on strict verified indication. | Use of an immunosuppressant. | |

| Panaccione et al., 2004 [8] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 8 | After three doses | Dosage increasement to 10 mg kg−1 or shortening of infusion intervals | Concomitant immunosuppressive therapy (eg, 6-MP, AZA or MTX) | |

| UC | Centocor, 2009 [61] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 8 | After three doses | NA | NA |

| AGA, 2007 [4]*** | |||||||

| RA | Centocor, 2009 [61] | 3 | 0,2,6 | 8 | 12 weeks | Options: - Increase the dose step-wise by approximately 1.5 mg kg−1, up to a maximum of 7.5 mg kg−1 every 8 weeks or - Administration of 3 mg kg−1 as often as every 4 weeks may be considered. | MTX |

| Furst et al., 2008 [9] | NA | NA | NA | Within 12–24 weeks | Increasing the dose or reducing the dosing intervals may provide additional benefit in RA, as may the addition or substitution of other DMARDs. | MTX | |

| NICE, 2007 [11] | 3 | 0,2,6 | 8 | 6 months | Options: - Increase the dose step-wise by approximately 1.5 mg kg−1, up to a maximum of 7.5 mg kg−1 every 8 weeks or - Administration of 3 mg kg−1 as often as every 4 weeks may be considered. | MTX | |

| NVR, 2003 [12] | NA | NA | NA | 12 weeks | Increasing dose or reducing the infusion intervals | NA | |

| FSR, 2007 [13] | 3 | 0,2,6 | 8 | 12 weeks | Changes can be made in the dosing interval (every 6 to 8 weeks) or dosage (3 to 5 mg kg−1), or the patient can be switched to another TNFα antagonist | MTX or another DMARD | |

| JCR, 2007 [14] | 3 | 0,2,6 | 8 | NA | Increment of dosage or shortening of interval is not allowed | MTX at a dose of 6–8mg week−1 | |

| ACR, 2008 [17] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | MTX | |

| BSR, 2005 [16] | NA | NA | NA | 3 months | NA | MTX | |

| AS | Centocor, 2009 [61] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 6 to 8 | After two doses | NA | NA |

| Furst et al., 2008 [9] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 6 to 8 | 6–12 weeks | NA | None | |

| NICE, 2008 [23] | Infliximab is not recommended for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis | ||||||

| FSR, 2007 [22] | NA | NA | NA | 6–12 weeks | Changes in dosage or dosing interval or the the patient can be switched to another TNFα antagonist | None | |

| Braun et al., 2006 [18] | 5 | NA | 6 to 8 | 6–12 weeks | NA | None | |

| BSR, 2005 [21] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 6 to 8 | 12 weeks and every 3 months thereafter | NA | NA | |

| NVR, 2005 [19] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 6 | 6–12 weeks and every 6 months thereafter | NA | None | |

| CRA, 2002 [57] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 8 | NA | NA | None | |

| PsA | Centocor, 2009 [61] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 8 | NA | NA | MTX |

| AAD, 2008 [60] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 6 to 8 | NA | Dose and interval of infusion may be adjusted as needed. | NA | |

| FSR, 2007 [22] | NA | NA | NA | 6–12 weeks | Changes in dosage or dosing interval or the the patient can be switched to another TNFα antagonist | None | |

| NICE, 2007 [24] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 8 | 12 weeks | NA | MTX**** | |

| Furst et al., 2008 [9] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Ps | Centocor, 2009 [61] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 8 | 14 weeks (four doses) | NA | None |

| Reich et al., 2008 [25] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 8 | 12 weeks (or three doses) | Decreasing the interval between infusions (e.g. from every 8 weeks to every 6 weeks), increasing the dose of drug administered and/or introducing a supplementary therapy such as a topical treatment or MTX. | None | |

| BAD, 2005 [26] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 8 | NA | NA | ***** | |

| NVDV, 2005 [27] | 3–10 mg kg−1** | 0,2,6 | 8 | 8 weeks | NA | None | |

| AAD, 2008 [36] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 6 to 8 | NA | Dose and interval of infusion may be adjusted as needed. | NA | |

| Sterry et al. 2004 [58] | 5 or 10 | 0,2,6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| NICE, 2008 [59] | 5 | 0,2,6 | 8 | 10 weeks | NA | NA | |

Period after which treatment with IFX should be stopped in case of non-response.

A definitive recommended dose has not been determined yet.

See section on Crohn's disease. No distinction is made in the AGA consensus statement between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.

Following the Summary of Product Characteristics.

Concomitant systemic therapies may be indicated for some patients with very severe unstable psoriasis, although doses of these should be minimized. AZA, azathioprine; MP, mercaptopurine; MTX, methotrexate; NA, no advice given.

Rheumatology

In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the standard dosage of infliximab administered recommended by most guidelines is 3 mg kg−1 bodyweight in an induction regimen at 0, 2 and 6, and thereafter every 8 weeks [11, 13, 14]. Some of the national and international guidelines do not explicitly state that infliximab should be administered at 3 mg kg−1 bodyweight, but rather assume that clinicians will administer this ‘standard dosage’[9, 12, 17]. As for patients with inflammatory bowel disease, if guidelines refer to attenuation of response, the dosage should be increased or the dosing interval shortened, together with the addition or substitution of another DMARD [9]. The Japanese guideline, however, does not allow any increment of dosage or shortening of interval, and some guidelines do not give recommendations regarding this topic [12, 14, 17]. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline is most explicit in its recommendation, recommending increasing the dose of infliximab stepwise by approximately 1.5 mg kg−1, up to a maximum of 7.5 mg kg−1 every 8 weeks, or alternatively administering of 3 mg kg−1 as often as every 4 weeks [11]. Recommended dosages from the reviewed guidelines and consensus statements regarding the specific diseases as well as the recommended dosage from the manufacturer are given in Table 2.

Dermatology

The guidelines on the treatment of psoriasis with biologicals from the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD), BAD and the international consensus panel of dermatology experts advises dosing infliximab in a 5 mg kg−1 infusion schedule at 0, 2 and 6 weeks, followed by maintenance treatment every 6–8 weeks (Table 2) [25, 26, 36]. The British guidelines however, state that no studies have been performed to establish the optimal dose or frequency of repeated infusions required in order to achieve disease control [26]. The dermatology guidelines give no clear recommendation regarding how to manage attenuated response to infliximab (Table 2).

Synergy

Repeated administration of infliximab has been associated with immunogenicity, i.e. the formation of antibodies to infliximab (ATI also known as HACA; human anti-chimeric antibodies). The concomitant use of immunosuppressants may increase the efficacy of infliximab, partly because it prevents the development of immunogenicity, and partially by other mechanisms currently unknown [37–39].

Gastroenterology

The international ECCO guideline has been very clear and advocates that every patient receiving infliximab should receive an immunomodulator (i.e. azathioprine, methotrexate or 6-mercaptopurine) in order to prevent development of antibodies against infliximab that in turn may reduce efficacy and increase side effects [6]. The consensus statement of the AGA strongly recommends co-administration with immunosuppressive therapy as well [4]. The Canadian guidelines are most clear by recommending that all patients, even if they failed to respond to immunomodulators in the past, should receive concomitant immunosuppressants [8]. The Dutch national guideline recommends initiation of immunosuppressants prior to infliximab in order to reduce the formation of antibodies [7].

Rheumatology

Nearly all efficacy studies with infliximab in rheumatoid arthritis patients have been performed in patients receiving concomitant methotrexate [29]. Therefore, all international, national and local guidelines recommend concomitant treatment with methotrexate in case of starting treatment with any anti-TNFα agent, including infliximab [13, 17].

Dermatology

The AAD does not recommend concomitant prescription of low-dose methotrexate, although some dermatologists do so to decrease the formation of antibodies [36]. The international consensus statement on the treatment of psoriasis with infliximab does not provide guidelines on the use of concomitant medication and the British guideline states that concomitant systemic therapies may be indicated for some patients with very severe or unstable psoriasis, although doses should be minimized [25, 26].

Monitoring of vital signs

As a foreign protein-derived agent administered intravenously over a 2 h infusion period, infliximab can cause infusion reactions. Formation of antibodies to infliximab may increase the risk of infusion reactions [37, 39]. These infusion reactions can be categorized as acute or delayed. An acute infusion reaction is defined as any adverse event occurring during infusion or within a period of 24 h after infusion [37, 40]. Severity can vary from mild to severe life threatening, and symptoms may include nausea, flushing, dizziness, dyspnoea, chest pain and hypotension or hypertension. Delayed infusion reactions are defined as reactions occurring from 24 h to 14 days after treatment with infliximab and symptoms may include arthralgia, rash, myalgia and fatigue [37, 40].

In randomized controlled trials with infliximab, vital signs (blood pressure, body temperature and pulse) were monitored vigorously. Monitoring body temperature at baseline is performed to rule out fever possibly based on infection and monitoring during infusion is performed while concerns exist about developing fever during an acute infusion reaction. The monitoring of blood pressure and pulse is based on the concern that during infusion with infliximab an anaphylactic shock could develop with typical hypotension.

Gastroenterology

Study protocols with infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease patients and some experts state that 30 min prior to, every 30 min during infusion and up till 2 h after infusion, vital signs (blood pressure, body temperature and pulse) should be monitored [41]. Randomized controlled trials in patients with inflammatory bowel disease reported incidences of acute infusion reactions ranging from 9–17% [35, 42]. In clinical practice the overall incidence of acute infusion reactions with infliximab is approximately 4–10% [40, 43]. None of the international or national guidelines state that during infusion, vital signs should be monitored. However, in general it is common practice to monitor vital signs during infusion with infliximab.

Rheumatology and dermatology

As in gastroenterology, current practice in rheumatology and dermatology is to monitor vital signs of patients during infusion with infliximab. However, none of the guidelines give specific recommendations regarding monitoring of vital signs.

Interpretation

With the exception of patients treated for rheumatoid arthritis who are treated with a dosage of 3 mg kg−1 bodyweight, all patients who are treated with infliximab receive a dosage of 5 mg kg−1 bodyweight (Table 2). To our knowledge, however, randomized controlled trials comparing response rates between 3 mg kg−1 or 5 mg kg−1 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis or psoriasis have not been performed. Klotz et al. reviewed the current knowledge on clinical pharmacokinetics of infliximab and stated that little detailed information was available yet and was solely based on measurements of serum concentrations by ELISA using monoclonal antibodies [44]. Indeed, several studies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis and psoriasis have shown that there is an inter-individual variability of infliximab pharmacokinetics associated with an increase in clinical response with infliximab trough serum concentrations [45–49]. In these studies, however, some patients showed good clinical response to infliximab with undetectable serum concentrations of infliximab, indicating that the correlation between serum concentrations and clinical response is still imprecise. On the other hand, a small observational open label study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis routinely treated with infliximab, showed that the measurement of trough infliximab concentration modified the therapeutic decision for half of their patients and led to improved control of disease activity for patients for whom infliximab dosage was increased [50]. Furthermore with regards to the pharmacokinetics of infliximab, the presence of ATI or HACA, which is associated with an increased risk of infusion reactions and a reduced duration of response, alter the pharmacokinetics of infliximab by an approximately 2.7 fold increase in systemic clearance [51]. Taken together, these findings indicate that further investigations regarding the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of infliximab are warranted in order to individualize the dosage, based on at least the trough serum concentration and the existence of ATI, thereby optimizing clinical response and cost effectiveness.

Regarding attenuation of response, the guidelines of each specialty recommend dosage increase or interval shortening or changing to another biological therapy. However, there is no clear recommendation which option should be chosen in which subset of patients. Pharmacokinetic modelling of infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed that interval reduction might be more effective in raising serum infliximab concentrations than dosage increase [46]. Flendrie et al. observed in an open-label study a more pronounced efficacy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving interval reduction, compared with patients receiving a dosage increase [52]. These observations need to be studied in large randomized trials.

With the exception of ankylosing spondylitis, the need for concomitant administration of immunosuppressants during treatment with infliximab has been stressed by most of the guidelines throughout the different specialties, since it appears to prevent the development of antibodies against infliximab [37–39]. However, benefits and risks of combined strategies should be balanced carefully as the evidence for increased risks of combined therapies is growing. This is most established for serious infections, which is observed in patients with inflammatory bowel disease [53, 54].

Monitoring of vital signs during infusion with infliximab is based on strict regulations during clinical trials and still advocated in some treatment algorithms and guidelines [8, 41]. We recently showed that scheduled monitoring of vital signs during infusion did neither indicate nor predict development of acute infusion reactions [55]. When baseline vital signs from patients with and without acute infusion reactions were compared, no significant differences were observed. Furthermore, during an acute infusion reaction, vital signs did not show a significant change compared with baseline [55].

In conclusion, by reviewing current guidelines and consensus statements within the medical specialties of rheumatology, gastroenterology and dermatology on the use of infliximab for auto-inflammatory disorders, several topics (i.e. dosage of infliximab, monitoring of vital signs, use of concomitant medication and loss of response) were discussed and shortcomings in guidelines and consensus statements regarding these topics were identified. Based on this discussion, several recommendations have been made, as can be seen in Table 3. Finally, as stressed by a recent quality appraisal of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements on the use of biological agents in rheumatoid arthritis, guidelines should be explicit in their guidance [56], which has implications for the development of future guidelines.

Table 3.

Conclusions and recommendations

| Topics | Conclusions and recommendations |

|---|---|

| Dosage of infliximab | Based on several controlled clinical studies, certain standard dosage regimens for infliximab have been defined which probably need some re-evaluation in terms of improving benefit : risk ratios [44]. |

| Future studies are needed to study the pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic relationship of infliximab as a necessary step before therapeutic drug monitoring can be recommended in guidelines. | |

| Monitoring vital signs | Routine scheduled measurement of vital signs during infusion is not valuable in detecting acute infusion reactions and should only be performed in the case of an acute infusion reaction |

| We recommend to administer infliximab at an infusion unit under supervision of trained personnel. This approach enables direct interventions in case a patient reports symptoms. Baseline assessment of patients, including vital signs, should still be performed as normal clinical practice to rule out possible infections or other contraindications for infusion with infliximab. | |

| Use of concomitant medication | Efforts should be made to establish a reasonable time interval in which concomitant medication should be decreased. |

| Loss of response to infliximab | Although some evidence exists that interval reduction might be more effective in raising serum infliximab concentrations than dosage increase, large randomized trials are needed to observe whether or not interval reduction is superior to dosage increase and in which subset of patients, in order to be able to give guidance regarding loss of response in clinical guidelines. |

Conflicts of interest

Authors H.S. de Vries, W. Kievit and M.C.W. Creemers declare no conflicts of interest. M.G.H. van Oijen has received an unrestricted research grant from Abbott. D.J. de Jong has received fees for speaking, organizing education, consultancy and research from Abbott Nederland, Schering Plough, Falk Pharma GmbH, UCB Pharma, Ferring BV, Nycomed, Synthon Nijmegen, Vifor Pharma, Tramedico Weesp and Shire pharmaceuticals. R.J.B. Driessen has received funding from Merck Serono and Wyeth for research, carried out clinical trials for Wyeth, Schering-Plough, Centocor, Abbott, Merck Serono and Barrier Therapeutics and has received speaking and consulting fees from Wyeth and Schering-Plough and received reimbursement for attending a symposium from Merck Serono, Janssen-Cilag and Wyeth. E.M.G.J. de Jong serves as consultant for Biogen, Merck Serono, Wyeth, and Abbott and receives research grants from Schering-Plough, Abbott, Merck Serono, Wyeth, and Centocor.

Funding: Schering Plough provided an educational grant to independently facilitate this consensus meeting.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lowes MA, Bowcock AM, Krueger JG. Pathogenesis and therapy of psoriasis. Nature. 2007;445:866–73. doi: 10.1038/nature05663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott DL, Kingsley GH. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:704–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct055183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–34. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark M, Colombel JF, Feagan BC, Fedorak KN, Hanauer SB, Kamm MA, Mayer L, Regueiro C, Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Sands BE, Schreiber S, Targan S, Travis S, Vermeire S. American Gastroenterological Association Consensus Development Conference on the use of biologics in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease, June 21–23, 2006. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:312–39. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenstein GR, Yan SK, Bala M, Blank M, Sands BE. Infliximab maintenance treatment reduces hospitalizations, surgeries, and procedures in fistulizing Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:862–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Travis SPL, Stange EF, Lemann M, Oresland T, Chowers Y, Forbes A, D'Haens G, Kitis G, Cortot A, Prantera C, Marteau P, Colombel JF, Gionchetti P, Bouhnik Y, Tiret E, Kroesen J, Starlinger M, Mortensen NJ. European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: current management. Gut. 2006;55:i16–i35. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.081950b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hommes DW, Oldenburg B, van Bodegraven AA, van Hogezand RA, De Jong DJ, Romberg-Camps MJL, van der Woude J, Dijkstra G. Guidelines for treatment with infliximab for Crohn's disease. Neth J Med. 2006;64:219–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panaccione R, Fedorak RN, Aumais G, Bernstein CN, Bitton A, Croitoru K, Enns R, Feagan B, Fishman M, Greenberg G, Griffiths A, Marshall JK, Rasul I, Sadowski D, Seidman E, Steinhart H, Sutherland L, Walli E, Wild G, Williams CN, Zachos M. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology clinical practice guidelines: the use of infliximab in Crohn's disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18:503–8. doi: 10.1155/2004/670161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furst DE, Keystone EC, Kirkham B, Kavanaugh A, Fleischmann R, Mease P, Breedveld FC, Smolen JS, Kalden JR, Burmester GR, Braun J, Emery P, Winthrop K, Bresnihan B, De Benedetti F, Dörner T, Gibofsky A, Schiff MH, Sieper J, Singer N, Van Riel PL, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH. Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2008. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:2–25. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.100834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prevoo MLL, Vanthof MA, Kuper HH, Vanleeuwen MA, Vandeputte LBA, Vanriel PLCM. Modified disease-activity scores that include 28-joint counts – development and validation in a prospective longitudinal-study of patients with rheumatoid-arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:44–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillon A, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of Rheumatoid arthritis. October 2007. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA130guidance.pdf (last accessed 17 August 2010)

- 12.Medicijnen: Het toepassen van TNF blokkade in de behandeling van reumatoide arthritis. November 2003. Available at http://www.nvr.nl/uploads/51/320/NVR_Medicijnen_richtlijn_TNF-RA.pdf (last accessed 17 August 2010)

- 13.Fautrel B, Pham T, Mouterde G, Le Loët X, Goupille P, Guillemin F, Ravaud P, Cantagrel A, Dougados M, Puéchal X, Sibilia J, Soubrier M, Mariette X, Combe B. Recommendations of the French Society for Rheumatology regarding TNFalpha antagonist therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:627–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koike R, Takeuchi T, Eguchi K, Miyasaka N. Update on the Japanese guidelines for the use of infliximab and etanercept in rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol. 2007;17:451–8. doi: 10.1007/s10165-007-0626-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soderlin MK, Geborek P. Changing pattern in the prescription of biological treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. A 7-year follow-up of 1839 patients in southern Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:37–42. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.070714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ledingham J, Deighton C. Update on the British Society for Rheumatology guidelines for prescribing TNF alpha blockers in adults with rheumatoid arthritis (update of previous guidelines of April 2001) Rheumatology. 2005;44:157–63. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J, Finney C, Curtis JR, Paulus HE, Mudano A, Pisu M, Elkins-Melton M, Outman R, Allison JJ, Suarez Almazor M, Bridges SL, Jr, Chatham WW, Hochberg M, MacLean C, Mikuls T, Moreland LW, O'Dell J, Turkiewicz AM, Furst DE, American College of Rheumatology American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:762–84. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun J, Davis J, Dougados M, Sieper J, van der Linden S, van der Heijde D. First update of the international ASAS consensus statement for the use of anti-TNF agents in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:316–20. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.040758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, Franssen MJAM, Oostveen JCM, van Denderen JC, Leijsma MK, de Sonnaville PBJ, Nurmohamed MT, van der Linden Sj. Richtlijn voor de diagnostiek en behandeling van spondylitis ankylopoetica. 2009. Available at http://www.nvr.nl/uploads/237/131/NVR_Reumatische_ziekten_richtlijn_Bechterew.pdf (last accessed 17 August 2010)

- 20.Vanderlinden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis – A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keat A, Barkham N, Bhalla A, Gaffney K, Marzo-Ortega H, Paul S, Rogers F, Somerville M, Sturrock R, Wordsworth P, BSR Standards, Guidelines and Audit Working group BSR guidelines for prescribing TNF-alpha blockers in adults with ankylosing spondylitis. Report of a working party of the British Society for Rheumatology. Rheumatology. 2005;44:939–47. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pham T, Fautrel B, Dernis E, Goupille P, Guillemin F, Le Loët X, Ravaud P, Claudepierre P, Miceli-Richard C, de Bandt M, Breban M, Maillefert JF, Masson C, Saraux A, Schaeverbeke T, Wendling D, Mariette X, Combe B, Club Rhumatismes et Inflammation (CRI/SFR) Recommendations of the French Society for Rheumatology regarding TNF alpha antagonist therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis or psoriatic arthritis: 2007 update. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:638–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dillon A, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for ankylosing spondylitis. May 2008. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11992/40761/40761.pdf (last accessed 17 August 2010)

- 24.Dillon A, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of adults with psoriatric arthritis. 2007. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11582/33404/33404.pdf (last accessed 17 August 2010)

- 25.Reich K, Griffiths C, Barker J, Chimenti S, Daudén E, Giannetti A, Gniadecki R, Katsambas A, Langley R, Mrowietz U, Ogilvie A, Ortonne JP, Reider N, Saurat JH. Recommendations for the long-term treatment of psoriasis with infliximab: a dermatology expert group consensus. Dermatology. 2008;217:268–75. doi: 10.1159/000149970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith CH, Anstey AV, Barker JN, Burden AD, Chalmers RJ, Chandler D, Finlay AY, Griffiths CE, Jackson K, McHugh NJ, McKenna KE, Reynolds NJ, Ormerod AD, British Association of Dermatologists British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for use of biological interventions in psoriasis 2005. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:486–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nederlandse vereniging voor dermatologie en venereologie. Het toepassen van biologicals in de behandeling van patiënten met plaque psoriasis. December 2004. Available at http://www.huidziekten.nl/richtlijnen/nvdvbiologicals2005concept.doc (last accessed 17 August 2010)

- 28.Elliott MJ, Maini RN, Feldmann M, Kalden JR, Antoni C, Smolen JS, Leeb B, Breedveld FC, Macfarlane JD, Bijl H, Woody JN. Randomized double-blind comparison of chimeric monoclonal-antibody to tumor-necrosis-factor-alpha (Ca2) versus placebo in rheumatoid-arthritis. Lancet. 1994;344:1105–10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90628-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, Smolen JS, Davis D, Macfarlane JD, Antoni C, Leeb B, Elliott MJ, Woody JN, Schaible TF, Feldmann M. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1552–63. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199809)41:9<1552::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maini RN, Elliot MJ, Longfox A, Feldmann M, Kalden JR, Antonio C, Smolen JS, Leeb B, Breedveld FC, MacFarlane JD, Bijl H, Woody JN. Clinical-response of rheumatoid arthritis (Ra) to anti-TNF-alpha (Ca2) monoclonal antibody (Mab) is related to administered dose and persistence of circulating antibody. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:200. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, Mayer L, Present DH, Braakman T, DeWoody KL, Schaible TF, Rutgeerts PJ. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1029–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710093371502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCabe RP, Woody J, van Deventer S, Targan SR, Mayer L, van Hogezand R, Rutgeerts P, Hanauer SB, Podolsky D, Elson CO. A multicenter trial of cA2 anti-TNF chimeric monoclonal antibody in patients with active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:A962. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh CJ, Das KM, Gottlieb AB. Treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) monoclonal antibody dramatically decreases the clinical activity of psoriasis lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:829–30. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.105948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaudhari U, Romano P, Mulcahy LD, Dooley LT, Baker DG, Gottlieb AB. Efficacy and safety of infliximab monotherapy for plaque-type psoriasis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1842–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W, Rutgeerts P, ACCENT I Study Group Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menter A, Gottlieb A, Feldman SR, Van Voorhees AS, Leonardi CL, Gordon KB, Lebwohl M, Koo JY, Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Beutner KR, Bhushan R. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis – Section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Haens G, Carbonez A, Rutgeerts P. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:601–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolbink GJ, Vis M, Lems W, Voskuyl AE, de Groot E, Nurmohamed MT, Stapel S, Tak PP, Aarden L, Dijkmans B. Development of antiinfliximab antibodies and relationship to clinical response in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:711–5. doi: 10.1002/art.21671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Vries MK, Wolbink GJ, Stapel SO, de Groot ER, Dijkmans BA, Aarden LA, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE. Inefficacy of infliximab in ankylosing spondylitis is correlated with antibody formation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:133–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.057745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheifetz A, Smedley M, Martin S, Reiter M, Leone G, Mayer L, Plevy S. The incidence and management of infusion reactions to infliximab: a large center experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1315–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandborn WJ, Hanauer SB. Infliximab in the treatment of Crohn's disease: a user's guide for clinicians. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2962–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, de Villiers WJ, Present D, Sands BE, Colombel JF. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colombel JF, Loftus EV, Jr, Tremaine WJ, Egan LJ, Harmsen WS, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The safety profile of infliximab in patients with Crohn's disease: the Mayo Clinic experience in 500 patients. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:19–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klotz U, Teml A, Schwab M. Clinical pharmacokinetics and use of infliximab. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2007;46:645–60. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200746080-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seow CH, Newman A, Irwin SP, Steinhart AH, Silverberg MS, Greenberg GR. Trough serum infliximab: a predictive factor of clinical outcome for infliximab treatment in acute ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2010;59:49–54. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.183095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.St Clair EW, Wagner CL, Fasanmade AA, Wang B, Schaible T, Kavanaugh A, Keystone EC. The relationship of serum infliximab concentrations to clinical improvement in rheumatoid arthritis – Results from ATTRACT, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1451–9. doi: 10.1002/art.10302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maser EA, Villela R, Silverberg MS, Greenberg GR. Association of trough serum infliximab to clinical outcome after scheduled maintenance treatment for Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1248–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reich K, Nestle FO, Papp K, Ortonne JP, Evans R, Guzzo C, Li S, Dooley LT, Griffiths CE, EXPRESS study investigators Infliximab induction and maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a phase III, multicentre, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1367–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67566-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Vries MK, Wolbink GJ, Stapel SO, de Vrieze H, van Denderen JC, Dijkmans BA, Aarden LA, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE. Decreased clinical response to infliximab in ankylosing spondylitis is correlated with anti-infliximab formation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1252–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.072397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mulleman D, Méric JC, Paintaud G, Ducourau E, Magdelaine-Beuzelin C, Valat JP, Goupille P. Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique UMR 6239 GICC. Infliximab concentration monitoring improves the control of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R178. doi: 10.1186/ar2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ternant D, Aubourg A, Magdelaine-Beuzelin C, Degenne D, Watier H, Picon L, Paintaud G. Infliximab pharmacokinetics in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Ther Drug Monit. 2008;30:523–9. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e318180e300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flendrie M, Creemers MCW, Van Riel PLCM. Titration of infliximab treatment in rheumatoid arthritis patients based on response patterns. Rheumatology. 2007;46:146–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, Salzberg BA, Diamond RH, Chen DM, Pritchard ML, Sandborn WJ. Serious infections and mortality in association with therapies for Crohn's disease: TREAT registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:621–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fidder H, Schnitzler F, Ferrante M, Noman M, Katsanos K, Segaert S, Henckaerts L, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P. Long-term safety of infliximab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a single-centre cohort study. Gut. 2009;58:501–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.163642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Vries HS, Van Oijen MGH, van Hoven-van Loo KEJ, De Jong DJ. Monitoring vital signs during infusion with infliximab does neither indicate nor predict development of acute infusion reactions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:387–8. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318178d938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lopez-Olivo MA, Kallen MA, Ortiz Z, Skidmore B, Suarez-Almazor ME. Quality appraisal of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements on the use of biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum-Arthritis Care Res. 2008;59:1625–38. doi: 10.1002/art.24207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maksymowych WP, Inman RD, Gladman D, Thomson G, Stone M, Karsh J, Russell AS, Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) Canadian Rheumatology Association consensus on the use of anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha directed therapies in the treatment of spondyloarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1356–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sterry W, Barker J, Boehncke WH, Bos JD, Chimenti S, Christophers E, De La Brassinne M, Ferrandiz C, Griffiths C, Katsambas A, Kragballe K, Lynde C, Menter A, Ortonne JP, Papp K, Prinz J, Rzany B, Ronnevig J, Saurat JH, Stahle M, Stengel FM, Van De Kerkhof P, Voorhees J. Biological therapies in the systemic management of psoriasis: international consensus conference. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:3–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dillon A, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Infliximab for the treatment of adults with psoriasis. January 2008. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11910/38954/38954.pdf (last accessed 17 August 2010)

- 60.Gottlieb A, Korman NJ, Gordon KB, Feldman SR, Lebwohl M, Koo JY, Van Voorhees AS, Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Beutner KR, Bhushan R, Menter A. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis – Section 2. Psoriatic arthritis: Overview and guidelines of care for treatment with an emphasis on the biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:851–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Centocor Product Information. 2009. Availalble at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000240/WC500050888.pdf (last accessed 17 August 2010)

- 62.Knight DM, Trinh H, Le J, Siegel S, Shealy D, McDonough M, Scallon B, Moore MA, Vilcek J, Daddona P, Ghrayeb J. Construction and initial characterization of a mouse-human chimeric anti-TNF antibody. Mol Immunol. 1993;30:1443–1453. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(93)90106-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]