Abstract

AIM

To characterize the pattern of use and discontinuation of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in women with myocardial infarction (MI) before and after 2002, where the general use of HRT dropped drastically subsequent to the results of the Women's Health Initiative trial.

METHODS

All Danish women aged ≥40 years hospitalized with MI in the period 1997 to 2005 and their use of HRT were identified by individual-level-linkage of nationwide registers of hospitalization and drug dispensing from pharmacies. Characteristics associated with HRT use at time of MI and subsequent HRT discontinuation were analysed by multivariable logistic regression.

RESULTS

In the study period, 34 778 women were discharged after MI. Of these, 3979 (11.4%) received HRT at the time of MI and their most used categories of HRT were vaginal oestrogen and oral oestrogen alone (46.6% and 28.7%, respectively). The percentage of women who continued HRT during the first year after discharge was 85.0% in the period 2000–2002 and had decreased to 79.6% in the period 2003–2005. Vaginal oestrogen use was associated with overall discontinuation of HRT (odds ratio [OR] 1.37, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.10, 1.72), whereas use of oral oestrogen alone and use of oral cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen were associated with change of HRT after MI (OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.10, 4.93 and OR 2.94, 95% CI 1.35, 6.39, respectively).

CONCLUSION

The majority of women experiencing an MI during ongoing HRT continued HRT after discharge and this pattern of HRT use did not change markedly after 2002.

Keywords: discontinuation, hormone replacement therapy, myocardial infarction, postmenopausal

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Women who use HRT when they experience their MI generally continue using HRT.

We found a remarkably low increase in discontinuation after 2002, in contrast to the general drop in use of HRT.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

General use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) dropped drastically after 2002 when pivotal randomized trials showed increased risk of coronary artery disease and other complications with HRT.

HRT is not recommended for primary or secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and guidelines recommend discontinuation of HRT after myocardial infarction (MI).

It is unknown whether women actually discontinue HRT after MI.

Introduction

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was widely used for primary and secondary prevention of coronary artery disease in postmenopausal women until the late 1990s because several observational studies had shown cardioprotective effects [1]. In 1998, however, the randomized Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) reported that HRT did not reduce the overall rate of cardiovascular events in women with established coronary artery disease [2]. A few years later the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) trial compared HRT with placebo in women with no previous heart disease and was terminated prematurely in 2002, because women in the HRT group had increased risk of coronary artery disease, cardiovascular disease, venous thromboembolism, stroke and breast cancer [3]. Following the results of these two trials, HRT has not been recommended for primary or secondary prevention of coronary artery disease and current international treatment guidelines have recommended discontinuation of HRT in women after acute myocardial infarction (MI) [4–6]. General use of HRT dropped drastically after intense public focus on the WHI results, e.g. in Denmark the use of HRT subsequently more than halved [7–10]. Nevertheless, it is unknown whether women experiencing an MI during ongoing HRT have followed the same pattern of treatment discontinuation. The aim of our study was therefore to describe the nationwide pattern of use and discontinuation of HRT in a population of women discharged after MI before and after publication of the WHI results. We used nationwide registers of hospitalization to identify women with MI and registers of drug dispensing from pharmacies to identify their claimed prescriptions for HRT before and after MI.

Methods

All Danish citizens have a unique and permanent civil registration number which can be used to link information from different registers on the individual level. The Danish National Patient Register contains detailed information about all admissions to Danish hospitals since 1978. Each hospitalization is registered by one primary and, if appropriate, one or more secondary diagnoses according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), i.e. ICD-8 until 1994 and ICD-10 from 1994. Operations are classified according to the Danish Classification of Operations until 1996 and after that the Nordic Classification of Surgical Procedures [11].

The Danish Register of Medicinal Product Statistics holds information about all prescribed medication (classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] system) dispensed from pharmacies in Denmark since 1995. Pharmacies are required to register all prescriptions dispensed because all residents in Denmark are covered by a national health security system and have the cost of drugs partially reimbursed [12]. All deaths are registered within 14 days of occurrence in the Central Population Register.

Population

All women 40 years or older on 1 January 1997 who were admitted with a diagnosis of MI (ICD-10 I21–I22) in the period 1997 to 2005 were identified in the National Patient Register and included in the study. The MI diagnosis in the National Patient Register has previously been validated with a sensitivity of 91% and a positive predictive value of 93% [13]. Concomitant pharmacotherapy was defined as claimed prescriptions for β-adrenoceptor blockers (ATC code C07), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blockers (ATC code C09), statins (ATC code C10AA), clopidogrel (ATC code B01AC04), vitamin K antagonists (ATC code B01AA) and antidepressants (ATC code N06A) during the 180 days prior to admission for MI. Co-morbidity was defined according to the modified Ontario Acute Myocardial Infarction Mortality Prediction Rules by diagnosis from the index admission and 1 year prior to admission [14, 15]. The national registers do not contain information about left ventricular ejection fraction and their sensitivity for heart failure diagnosis is low [16]. We therefore used prescription of loop diuretics (ATC code C03C) as a proxy for heart failure, as done by Gislason et al.[17]. In a similar way, we used prescribed glucose-lowering medication (ATC code A10) as a proxy for pharmacologically treated diabetes mellitus. All patients who had suffered at least one prior MI (ICD-8 code 410 and ICD-10 codes I21–I22) or had a diagnosis of breast or genital cancers (ICD-8 codes 174 or 182–184 and ICD-10 codes C50 or C54–57) in the period from 1978 to the end of 1996 were identified. Information about coronary revascularizations, i.e. percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI, code KFNG) and coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG, codes KFNA-KFNE), as well as hysterectomies (codes 61000–61100 and KLCC-KLDE) was also obtained.

Use of hormone replacement therapy

For the period 1997 to 2006, we identified all claimed prescriptions for HRT in the Danish Register of Medicinal Product Statistics (ATC codes G03C, G03D, G03F, G03XC, and G02BA03). We did not include drugs usually used for contraceptive purposes except for a progesterone intrauterine device (IUD) which is commonly used in postmenopausal women. HRT covers a broad spectrum of chemical compounds, formulations, routes of administration and dosages. We organized this pharmacological multiplicity into six categories (Table 1): (i) oral oestrogen alone, (ii) oral continuous combined oestrogen/progestogen, (iii) oral cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen, (iv) transdermal oestrogen or oestrogen/progestogen (transdermal HRT), (v) vaginal oestrogen and (vi) ‘other HRT’. These categories were mutually exclusive, but some women used HRT of more than one category. Women who received concomitant prescriptions for both an oral oestrogen and a progestogen were classified as receiving oral cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen. The Danish Register of Medicinal Product Statistics includes information about the dispensing date of the prescription, strength and quantity of the medication. Daily drug dosage is not included in the register, but was estimated by calculating average dosage from up to three consecutive prescriptions prior to and after the actual prescription, constituting a treatment interval. This method allowed daily dosages to change from one treatment interval to another. The IUD was considered viable for up to 5 years.

Table 1.

Categories of hormone replacement therapy

| Hormone type | ATC codes |

|---|---|

| 1. Oral oestrogen alone | G03C A03, G03C A04, G03C A53, G03C A57 |

| 2. Oral continuous oestrogen /progestogen | G03F A01, G03FA11, G03F A12, G03F A15, G0F A17 |

| 3. Oral cyclic oestrogen/progestogen | G03F B05, G03F B06, G03F B01, G03F B09, G03H B01, or category 1 + progestogen from category 6 |

| 4. Transdermal oestrogen or oestrogen/ progestogen (Transdermal HRT) | G03C A03, G03F A01, G03F B05 |

| 5. Vaginal oestrogen | G03C A03, G03C A04, G03C A57, G03C B01 |

| 6. Other HRT: Oestrogen injection, progestogen intrauterine device, raloxifene, tibolone, progestogen alone | G03C A03, G02B A03, G03X C01, G03D C05, G03D A02, G03D A04, G03D C02, G03D C03 |

ATC Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical system, HRT hormone replacement therapy. Oral continuous oestrogen/progestogen: daily doses of both oestrogen and progestogen. Oral cyclic oestrogen/progestogen: daily doses of oestrogen and intermittent periods with daily doses of progestogen.

On the basis of these assumptions, we calculated whether or not HRT was available to patients and we defined women as receiving HRT if treatment was available. Discontinuation of HRT was determined when the women had no treatment available and there were no future prescription claims of HRT in that particular HRT category. This method has previously been described in details elsewhere [17]. Use of HRT after MI was defined for women who claimed an HRT prescription after discharge.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics and baseline variables are given as number and percentages or medians with inter-quartile range (IQR). Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to identify covariates associated with use of HRT at the time of MI, category of HRT, and discontinuation and change of category of HRT after MI. The models were adjusted for year of MI (the period 2000–2002 as reference), age (≥80 years as reference), concomitant pharmacotherapy (no pharmacotherapy as reference), and co-morbidity (no co-morbidity as reference). A level of 5% was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics

The Danish Data Protection Agency approved the study (No. 2007-41-1667). Retrospective register studies do not require ethical approval in Denmark. Data are available in such a way that no individuals can be identified.

Results

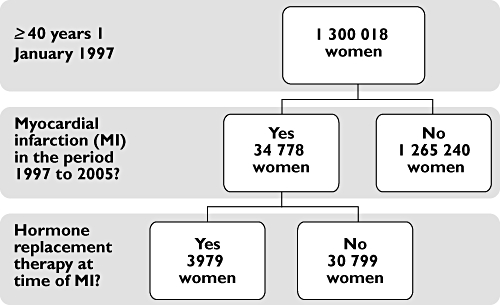

Out of the 1 300 018 Danish women who were 40 years or older on 1 January 1997, a total of 34 778 (2.7%) were admitted with an MI in the period 1997 to 2005 and were included in the study. The selection of the study population is illustrated in Figure 1. The two groups, i.e. the HRT group (3979 women [11.4%] who were treated with HRT at the time of admission for MI) and the non-HRT group (30 799 women who were not treated with HRT at the time of admission for MI), constituted the subgroups examined in this study and their baseline characteristics at the time of admission are shown in Table 2. Women in the HRT group were younger (71 years) than women in the non-HRT group (77 years).

Figure 1.

Study population

Table 2.

Baseline: women admitted with myocardial infarction from 1997 to 2005

| HRT group | Non-HRT group | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of women (%) | 3979 (11.4) | 30 799 (88.6) |

| Age, median, years (IQR) | 71 (62–79) | 77 (69–84) |

| Age group (years), n (%) | ||

| 40–59 | 780 (19.6) | 2 913 (9.5) |

| 60–69 | 1044 (26.2) | 5 110 (16.6) |

| 70–79 | 1195 (30.0) | 9 922 (32.2) |

| 80– | 960 (24.1) | 12 854 (41.7) |

| Year of MI, n (%) | ||

| 1997–1999 | 1142 (28.7) | 9 828 (31.9) |

| 2000–2002 | 1481 (37.2) | 10 853 (35.2) |

| 2003–2005 | 1356 (34.1) | 10 118 (32.9) |

| Co-morbidity, n (%) | ||

| Prior MI | 390 (9.8) | 3 495 (11.4) |

| Prior hysterectomy | 621 (15.6) | 1 889 (6.1) |

| Prior CABG | 76 (1.9) | 472 (1.5) |

| Prior PCI | 81 (2.0) | 307 (1.0) |

| Prior breast cancer | 86 (2.2) | 1 146 (3.7) |

| Prior genital cancer | 88 (2.2) | 562 (1.8) |

| Cerebrovascular disease* | 124 (3.1) | 1 167 (3.8) |

| Congestive heart failure* | 137 (3.4) | 1 520 (4.9) |

| Malignancy* | 79 (2.0) | 699 (2.3) |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias* | 165 (4.2) | 1 384 (4.5) |

| Chronic renal failure* | 18 (0.5) | 233 (0.8) |

| Acute renal failure* | 14 (0.4) | 146 (0.5) |

| Diabetes with complications* | 34 (0.9) | 432 (1.4) |

| Pulmonary oedema* | 15 (0.4) | 120 (0.4) |

| Shock* | 20 (0.5) | 142 (0.5) |

| Concomitant pharmacotherapy, n (%) | ||

| β-adrenoceptor blocker | 872 (21.9) | 6 245 (20.3) |

| ACE inhibitor | 942 (23.7) | 7 092 (23.0) |

| Statins | 398 (10.0) | 2 590 (8.4) |

| Loop diuretics | 857 (21.5) | 8 781 (28.5) |

| Clopidogrel | 48 (1.2) | 201 (0.7) |

| Glucose-lowering medication | 355 (8.9) | 4 015 (13.0) |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 126 (3.2) | 1 028 (3.3) |

| Antidepressants | 798 (20.1) | 4 730 (15.4) |

ACE inhibitor angiotensin-converting enzyme-inhibitor, CABG coronary arterial bypass graft, CI confidence interval, HRT hormone replacement therapy, IQR inter-quartile range, MI myocardial infarction, OR odds ratio, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention.

Co-morbidity according to the modified Ontario Acute Myocardial Infarction Mortality Prediction Rules.

Use of HRT at the time of MI

Results from a multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with use of HRT at time of MI are shown in Table 3. Women having a MI in the period 2000–2002 did not have a higher probability of using HRT at the time of MI than women experiencing MI in the period 2003–2005, but younger age was associated with HRT use. Prior hysterectomy or PCI (odds ratio [OR] 2.48, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.23, 2.76, and OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.23, 2.09, respectively), and use of β-adrenoceptor blockers, ACE inhibitors and antidepressants (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.05, 1.25, OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.05, 1.25, and OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.39, 1.65, respectively), were associated with HRT use, while loop diuretics (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.77, 0.92), glucose-lowering medication (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.56, 0.71) and prior breast and genital cancer (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.45, 0.70 and OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.51, 0.95, respectively) were associated with absence of HRT use.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with use of hormone replacement therapy at time of myocardial infarction

| Variable | HRT use | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age group (years) | ||

| 40–59 | 3.19 (2.86, 3.55) | <0.001 |

| 60–69 | 2.55 (2.32, 2.82) | <0.001 |

| 70–79 | 1.58 (1.44, 1.73) | <0.001 |

| 80– | 1.00 | – |

| Year of MI | ||

| 1997–1999 | 0.85 (0.78, 0.92) | <0.001 |

| 2000–2002 | 1.00 | – |

| 2003–2005 | 0.95 (0.88, 1.03) | NS |

| Co-morbidity | ||

| Hysterectomy | 2.48 (2.23, 2.76) | <0.001 |

| Prior MI | 1.00 (0.89, 1.13) | NS |

| Prior CABG | 1.03 (0.79, 1.34) | NS |

| Prior PCI | 1.61 (1.23, 2.09) | <0.001 |

| Malignancy | 0.90 (0.71, 1.05) | NS |

| Prior breast cancer | 0.56 (0.45, 0.70) | <0.001 |

| Prior genital cancer | 0.71 (0.51, 0.95) | 0.007 |

| Concomitant pharmacotherapy | ||

| β-adrenoceptor blocker | 1.14 (1.05, 1.25) | 0.002 |

| ACE inhibitor | 1.15 (1.05, 1.25) | 0.002 |

| Statins | 0.94 (0.83, 1.07) | NS |

| Loop diuretics | 0.84 (0.77, 0.92) | <0.001 |

| Glucose-lowering medication | 0.63 (0.56, 0.71) | <0.001 |

| Antidepressants | 1.52 (1.39, 1.65) | <0.001 |

ACE angiotensin converting enzyme, CABG coronary arterial bypass graft, CI confidence interval, HRT hormone replacement therapy, MI myocardial infarction, OR odds ratio, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention. Analysis of all 34 778 women with MI. Reference for concomitant pharmacotherapy and co-morbidity is no concomitant pharmacotherapy and no co-morbidity, respectively. A value of P > 0.05 is considered to be non-significant (NS).

Of the 34 778 women with MI, 8168 (23.5%) had claimed a prescription for HRT in the years from 1997 to their admission for MI (Table 4). The percentages of women receiving HRT at the time of MI in the periods 1997–99, 2000–2002 and 2003–2005 were 10.4%, 12.0% and 11.8%, respectively. In the HRT group, 3112 out of the 3979 women were alive after 365 days, and of these 2721 (87.4%) claimed HRT prescriptions in the years following discharge. Table 4 also shows information on the prescription pattern for women in the non-HRT group.

Table 4.

Use of hormone replacement therapy

| HRT group | Non-HRT group | |

|---|---|---|

| Women in the groups, n (%) | 3979 (100) | 30 799 (100) |

| Women alive 1 year after MI | 3112 (78.2) | 19 421 (63.1) |

| Women with HRT prescriptions 1997–2007, n (%) | ||

| Ever | 3979 (100) | 6 175 (20.0) |

| Before MI | 3979 (100) | 4 189 (13.6) |

| After MI | 2915 (73.3) | 2 914 (9.5) |

| Before and after MI | 2915 (73.3) | 928 (3.0) |

| Only before MI | 1064 (26.8) | 3 261 (11.7) |

| Only after MI | 0 | 1 986 (7.5) |

| Prescriptions for women alive 1 year after MI | ||

| Before MI | 3112 (100) | 2 869 (14.8) |

| After MI | 2721 (87.4) | 2 840 (14.6) |

| Before and after | 2721 (87.4) | 898 (4.6) |

| Only after MI | 0 | 1 942 (10.0) |

| Use of HRT categories before MI, n (%) | ||

| HRT overall | 3979 (100) | 4 189 (100) |

| Oral oestrogen alone | 1196 (30.1) | 662 (15.8) |

| Continuous combined oestrogen/progestogen | 841 (21.1) | 453 (10.8) |

| Cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen | 744 (18.7) | 414 (9.8) |

| Transdermal HRT | 242 (6.1) | 208 (5.0) |

| Vaginal oestrogen | 1644 (41.3) | 2 798 (66.8) |

| Other HT | 398 (10.0) | 297 (7.1) |

| Use of HRT categories at time of MI, n (%) | ||

| HRT overall | 3979 (100) | – |

| Oral oestrogen alone | 1123 (28.2) | – |

| Continuous combined oestrogen/progestogen | 720 (18.1) | – |

| Cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen | 440 (11.1) | – |

| Transdermal HRT | 132 (3.3) | – |

| Vaginal oestrogen | 1382 (34.7) | – |

| Other HRT | 320 (8.0) | – |

| Overall use of HRT categories after MI, n (%) | ||

| HRT overall | 2915 (100) | 2 914 (100) |

| Oral oestrogen alone | 836 (28.7) | 211 (7.2) |

| Continuous combined oestrogen/progestogen | 689 (23.6) | 156 (5.3) |

| Cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen | 362 (12.4) | 114 (3.9) |

| Transdermal HRT | 149 (5.1) | 57 (2.0) |

| Vaginal oestrogen | 1358 (46.6) | 2 464 (84.6) |

| Other HRT | 271 (9.3) | 164 (5.6) |

HRT hormone replacement therapy, MI myocardial infarction. Some women used HRT from more than one category, which is why the sum of use of the different HRT categories is >100%.

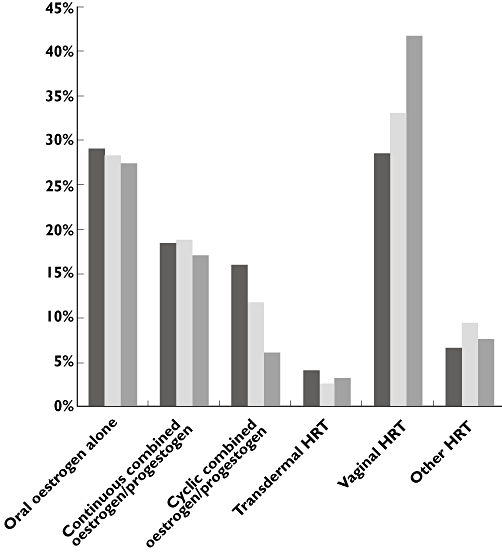

Category of HRT

In both the HRT group and the non-HRT group, vaginal oestrogen was the most widely used category of HRT, followed by oral oestrogen alone and continuous combined oestrogen/progestogen (Table 4 and Figure 2). Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with use of the six different categories of HRT in women who used only one category of HRT at the time of MI (n = 3 842) showed that younger age increased the chance of receiving oral continuous combined or cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen, transdermal HRT or ‘other HRT’, whereas older age was associated with use of oral oestrogen alone and vaginal oestrogen (Table 5). Hysterectomy was associated with use of oral oestrogen and transdermal HRT (OR 11.50, 95% CI 9.25, 14.31 and OR 2.87, 95% CI 1.86, 4.42, respectively), but lowered the chance of receiving the other categories of HRT. Women experiencing MI in the period 1997–1999 were more likely to use oral cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen and transdermal HRT and less likely to use ‘other HRT’, whereas women with MI in the period 2003–2005 were more likely to use vaginal oestrogen and less likely to use oral cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.15, 1.64 and OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.41, 0.76, respectively). Prior breast or genital cancers lowered the likelihood of receiving oral oestrogen (OR 0.27, 95% CI 0.13, 0.55, and OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.22, 0.61, respectively), but prior breast cancer was associated with use of transdermal HRT and vaginal oestrogen (OR 4.35, 95% CI 1.57, 12.07 and OR 3.38, 95% CI 2.04, 5.60, respectively).

Figure 2.

Hormone replacement therapy categories used at time of myocardial infarction. HRT hormone replacement therapy. 1997–1999 ( ); 2000–2002 (

); 2000–2002 ( ); 2003–2005 (

); 2003–2005 ( )

)

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with use of the different categories of hormone replacement therapy at the time of myocardial infarction

| Variable | Oral oestrogen alone | Oral continuous combined oestrogen/progestogen | Oral cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen | Transdermal oestrogen | Vaginal oestrogen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | Other | P value | |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||||

| 40–59 | 0.47 (0.36, 0.61) | <0.001 | 8.06 (5.69, 11.42) | <0.001 | 18.39 (11.40, 29.64) | <0.001 | 8.74 (3.59, 21.24) | <0.001 | 0.06 (0.04, 0.08) | <0.001 | 2.33 (1.55, 3.51) | <0.001 |

| 60–69 | 0.68 (0.54, 0.86) | 0.001 | 9.21 (6.61, 12.82) | <0.001 | 6.87 (4.25, 11.11) | <0.001 | 4.10 (1.67, 10.10) | 0.002 | 0.19 (0.15, 0.23) | <0.001 | 1.62 (1.08, 2.42) | 0.02 |

| 70–79 | 1.10 (0.89, 1.35) | NS | 3.81 (2.73, 5.31) | <0.001 | 2.46 (1.48, 4.09) | <0.001 | 1.38 (0.51, 3.73) | NS | 0.42 (0.35, 0.50) | <0.001 | 1.78 (1.23, 2.59) | 0.002 |

| 80– | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | |

| Year of MI | ||||||||||||

| 1997–1999 | 1.21 (0.99, 1.46) | NS | 0.82 (0.66, 1.01) | NS | 1.30 (1.02, 1.66) | 0.03 | 1.75 (1.04, 2.94) | 0.03 | 0.94 (0.78, 1.14) | NS | 0.58 (0.42, 0.80) | <0.001 |

| 2000–2002 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| 2003–2005 | 0.88 (0.73, 1.06) | NS | 1.04 (0.84, 1.29) | NS | 0.56 (0.41, 0.75) | <0.001 | 1.61 (0.96, 2.71) | NS | 1.37 (1.15, 1.64) | 0.005 | 0.84 (0.63, 1.13) | NS |

| Co-morbidity | ||||||||||||

| Hysterectomy | 11.50 (9.25, 14.31) | <0.001 | 0.12 (0.08, 0.18) | <0.001 | 0.17 (0.11, 0.27) | <0.001 | 2.87 (1.86, 4.42) | <0.001 | 0.32 (0.24, 0.42) | <0.001 | 0.35 (0.22, 0.57) | <0.001 |

| Prior MI | 1.06 (0.81, 1.39) | NS | 0.77 (0.61, 1.22) | NS | 0.90 (0.59, 1.38) | NS | 1.09 (0.50, 2.39) | NS | 1.00 (0.77, 1.29) | NS | 1.16 (0.74, 1.82) | NS |

| Prior CABG | 0.83 (0.45, 1.51) | NS | 0.91 (0.44, 1.88) | NS | 1.19 (0.53, 2.69) | NS | 0.38 (0.05, 3.01) | NS | 1.42 (0.82, 2.47) | NS | 0.79 (0.27, 2.27) | NS |

| Prior PCI | 3.47 (2.05, 5.86) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.37, 1.47) | NS | 0.95 (0.45, 2.02) | NS | No observations | – | 0.48 (0.25, 0.90) | 0.02 | 0.97 (0.37, 2.54) | NS |

| Malignancy | 0.64 (0.35, 1.19) | NS | 1.36 (0.70, 2.63) | NS | 1.30 (0.55, 3.10) | NS | 0.92 (0.20, 4.20) | NS | 1.01 (0.59, 1.72) | NS | 1.13 (0.47, 2.71) | NS |

| Prior breast cancer | 0.27 (0.13, 0.55) | 0.003 | 0.53 (0.25, 1.15) | NS | 0.15 (0.02, 1.09) | NS | 4.35 (1.57, 12.07) | 0.005 | 3.38 (2.04, 5.60) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.34, 2.18) | NS |

| Prior genital cancer | 0.37 (0.22, 0.61) | <0.001 | 1.23 (0.50, 3.06) | NS | 1.76 (0.59, 5.21) | NS | 0.96 (0.28, 3.34) | NS | 1.49 (0.88, 2.53) | NS | 2.69 (1.19, 6.07) | 0.02 |

| Concomitant pharmacotherapy | ||||||||||||

| β-adrenoceptor blocker | 0.92 (0.76, 1.12) | NS | 1.03 (0.82, 1.29) | NS | 0.89 (0.66, 1.20) | NS | 1.07 (0.63, 1.80) | NS | 1.09 (0.91, 1.31) | NS | 0.95 (0.69, 1.31) | NS |

| ACE inhibitor | 1.07 (0.89, 1.30) | NS | 0.98 (0.78, 1.22) | NS | 0.75 (0.56, 1.02) | NS | 1.74 (1.07, 2.81) | 0.02 | 1.02 (0.86, 1.23) | NS | 0.89 (0.65, 1.23) | NS |

| Statins | 0.89 (0.67, 1.19) | NS | 0.60 (0.42, 0.84) | 0.003 | 1.16 (0.78, 1.72) | NS | 1.46 (0.79, 2.73) | NS | 1.52 (1.17, 1.99) | 0.002 | 0.76 (0.47, 1.24) | NS |

| Loop diuretics | 1.21 (0.99, 1.47) | NS | 1.06 (0.83, 1.36) | NS | 0.99 (0.72, 1.38) | NS | 0.53 (0.25, 1.09) | NS | 0.86 (0.71, 1.04) | NS | 1.06 (0.76, 1.48) | NS |

| Glucose-lowering medication | 0.75 (0.57, 1.01) | NS | 0.67 (0.48, 0.96) | 0.03 | 0.86 (0.56, 1.32) | NS | 0.67 (0.28, 1.59) | NS | 1.88 (1.46, 2.43) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.53, 1.38) | NS |

| Antidepressants | 1.02 (0.84, 1.24) | NS | 1.25 (1.00, 1.54) | <0.05 | 1.02 (0.76, 1.35) | NS | 0.36 (0.17, 0.76) | 0.01 | 0.98 (0.81, 1, 18) | NS | 0.84 (0.61, 1.17) | NS |

ACE angiotensin converting enzyme, CABG coronary arterial bypass graft, CI confidence interval, HRT hormone replacement therapy, MI myocardial infarction, OR odds ratio, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention. This analysis including only the 3842 women who used only one category of HRT at the time of MI. Reference for concomitant pharmacotherapy and co-morbidity is no concomitant pharmacotherapy and no co-morbidity, respectively. A value of P > 0.05 is considered to be non-significant (NS).

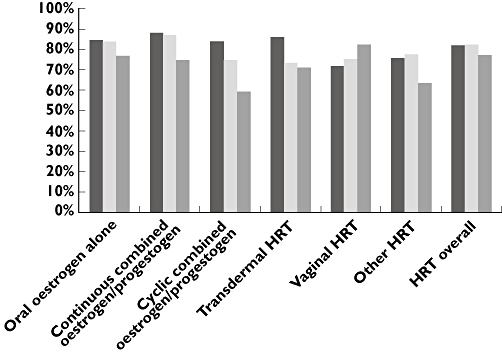

Discontinuation and change of HRT

In the periods 1997–1999 and 2000–2002 the proportion of women in the HRT group who were alive 1 year after MI and claimed any HRT prescription during the first 365 days after discharge was 85.2% and 85.0%, respectively. This percentage had dropped to 79.6% in 2003–2005 (not shown). Figure 3 shows the percentage of women alive 1 year after MI who claimed at least one prescription for the same category of HRT they used at the time of MI. Overall there was a small increase in HRT discontinuation from 2000–2002 to 2003–2005 as the percentage of women who continued same category of HRT decreased from 82.5% to 77.3%. HRT discontinuation varied considerably between categories of HRT and increased for all categories in the period 2003–2005, except for vaginal oestrogen. Especially oral cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen showed a large increase in discontinuation from 25% to 41%.

Figure 3.

Proportion of women continuing use of same category of hormone replacement therapy the first year after MI, out of women still alive. HRT hormone replacement therapy, MI myocardial infarction. 1997–1999 ( ); 2000–2002 (

); 2000–2002 ( ); 2003–2005 (

); 2003–2005 ( )

)

As seen in Table 6, the multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with change from one HRT category to another after MI showed that use of oral oestrogen alone and use of oral cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen were associated with change of HRT (OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.10, 4.93 and OR 2.94, 95% CI 1.35, 6.39, respectively) and that use of vaginal oestrogen was associated with a lower likelihood of HRT change (OR 0.11, 95% CI 0.02, 0.50). MI in the period 2003–2005 as well as higher age and malignancy in the year prior to MI were associated with overall discontinuation of HRT after MI. The same was seen for use of vaginal oestrogen (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.10, 1.72), ‘other HRT’ (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.20, 2.23), loop diuretics (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.21, 1.72), glucose-lowering medication (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.06, 1.72) and antidepressants (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.11, 1.57), whereas hysterectomy and prior PCI lowered the likelihood of discontinuation of HRT (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.57, 0.93 and OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.24, 0.90, respectively). The same pattern was seen for discontinuation of the respective category of HRT used at the time of MI, which was also associated with use of oral oestrogen alone.

Table 6.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with discontinuation or change of hormone replacement therapy after myocardial infarction

| Discontinuation of category of HRT that was used at time of MI | Discontinuation of all categories of HRT | Change of HRT after MI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 40–59 | 0.49 (0.38, 0.62) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.36, 0.60) | <0.001 | 1.60 (0.63, 4.10) | NS |

| 60–69 | 0.53 (0.43, 0.66) | <0.001 | 0.50 (0.41, 0.63) | <0.001 | 1.99 (0.83, 4.76) | NS |

| 70–79 | 0.72 (0.59, 0.86) | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.58, 0.84) | <0.001 | 1.70 (0.73, 3.95) | NS |

| 80– | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Year of MI | ||||||

| 1997–1999 | 1.13 (0.95, 1.34) | NS | 1.13 (0.94, 1.35) | NS | 1.07 (0.59, 1.93) | NS |

| 2000–2002 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| 2003–2005 | 1.22 (1.03, 1.44) | 0.02 | 1.20 (1.01, 1.42) | 0.04 | 1.46 (0.81, 2.62) | NS |

| Co-morbidity | ||||||

| Hysterectomy | 0.71 (0.56, 0.90) | 0.004 | 0.73 (0.57, 0.93) | 0.01 | 0.67 (0.33, 1.38) | NS |

| Prior MI | 0.91 (0.71, 1.16) | NS | 0.88 (0.68, 1.13) | NS | 1.41 (0.63, 3.17) | NS |

| Prior CABG | 0.97 (0.56, 1.68) | NS | 0.99 (0.57, 1.73) | NS | 0.79 (0.10, 6.44) | NS |

| Prior PCI | 0.51 (0.28, 0.95) | 0.03 | 0.47 (0.24, 0.90) | 0.02 | 1.29 (0.28, 6.00) | NS |

| Malignancy | 2.55 (1.57, 4.13) | <0.001 | 2.47 (1.52, 4.00) | <0.001 | 1.67 (0.37, 7.42) | NS |

| Prior breast cancer | 0.80 (0.49, 1.30) | NS | 0.79 (0.48, 1.28) | NS | 1.28 (0.16, 10.28) | NS |

| Prior genital cancer | 1.47 (0.92, 2.37) | NS | 1.36 (0.84, 2.20) | NS | 2.45 (0.67, 8.98) | NS |

| Concomitant pharmacotherapy | ||||||

| β-adrenoceptor blocker | 0.91 (0.77, 1.09) | NS | 0.93 (0.78, 1.11) | NS | 0.81 (0.42, 1.55) | NS |

| ACE inhibitor | 0.81 (0.68, 0.96) | 0.02 | 0.82 (0.69, 0.97) | 0.02 | 0.79 (0.42, 1.50) | NS |

| Statins | 0.96 (0.75, 1.24) | NS | 1.00 (0.77, 1.30) | NS | 0.59 (0.21, 1.63) | NS |

| Loop diuretics | 1.43 (1.20, 1.70) | <0.001 | 1.44 (1.21, 1.72) | <0.001 | 1.03 (0.54, 1.96) | NS |

| Glucose-lowering medication | 1.42 (1.12, 1.80) | 0.004 | 1.35 (1.06, 1.72) | 0.02 | 2.12 (1.00, 4.53) | NS |

| Antidepressants | 1.28 (1.08, 1.52) | 0.004 | 1.32 (1.11, 1.57) | 0.002 | 0.75 (0.39, 1.45) | NS |

| Type of HRT | ||||||

| Oral oestrogen alone | 1.26 (1.00, 1.60) | <0.05 | 1.17 (0.92, 1.48) | NS | 2.33 (1.10, 4.93) | 0.03 |

| Continuous combined oestrogen/progestogen | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Cyclic combined oestrogen/progestogen | 1.16 (0.88, 1.54) | NS | 1.00 (0.75, 1.35) | NS | 2.94 (1.35, 6.39) | 0.007 |

| Transdermal HRT | 1.26 (0.77, 2.06) | NS | 1.23 (0.74, 2.03) | NS | 1.42 (0.30, 6.69) | NS |

| Vaginal oestrogen | 1.29 (1.03, 1.62) | 0.02 | 1.37 (1.10, 1.72) | 0.006 | 0.11 (0.02, 0.50) | 0.005 |

| Other HRT | 1.67 (1.23, 2.26) | 0.001 | 1.64 (1.20, 2.23) | 0.002 | 1.47 (0.53, 4.06) | NS |

ACE angiotensin converting enzyme, CABG coronary arterial bypass graft, CI confidence interval, HRT hormone replacement therapy, MI myocardial infarction, OR odds ratio, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention. This analysis including only the 3842 women who used only one category of HRT at the time of MI. Reference for concomitant pharmacotherapy and co-morbidity is no concomitant pharmacotherapy and no co-morbidity, respectively. Discontinuation: No prescription claims first 365 days after MI. Change of HRT: Discontinuation of the category of HRT used at the time of MI, but new prescription for different category of HRT first 365 days after MI. A value of P > 0.05 is considered to be non-significant (NS).

Discussion

The present study is to our knowledge the first to address the use of HRT and its discontinuation in a nationwide cohort of women with MI. The main findings were: (i) the proportion of Danish women using HRT at the time of their MI was largely unaffected by the 2002 publication of the WHI results in spite of the general drop in HRT use, (ii) the most used category of HRT at the time of MI was vaginal oestrogen, followed by oral oestrogen alone and continuous combined oestrogen/progestogen, both before and after 2002, (iii) the vast majority of women did not discontinue overall HRT after MI, although variations of discontinuation rates were observed between different categories of HRT and a slight increase in discontinuation was seen after 2002 and (iv) discontinuation of overall HRT after MI was associated with higher age, MI in the period 2003–2005, malignancy in the year prior to MI and use of vaginal or ‘other’ HRT, while hysterectomy and prior PCI lowered the likelihood of HRT discontinuation.

In our population of women ≥40 years, women who used HRT at the time of MI were younger than women who did not. This was probably due to the fact that it is mainly women of younger age who use HRT, as previously observed in the Danish population [7]. Other explanations may be that women taking HRT may have increased risk of MI due to HRT in itself or women with severe menopausal symptoms requiring HRT for symptom relief may have increased biological risk of MI when compared with women without menopausal symptoms [2, 3]. The latter explanation is supported by the finding that women with menopausal symptoms have more aortic calcification and lower flow-mediated vasodilatation than women without menopausal symptoms, indicating a higher risk of coronary artery disease [18]. We found that a total of 23.5% of women with MI had claimed prescriptions of HRT in the years prior to MI. This figure is undoubtedly underestimated, since it does not include the women claiming HRT prescriptions prior to the beginning of our study period and the median age of the women was >70 years. The average age of reaching menopause in Denmark is 51 years [19]. Our decision to include women ≥40 years on 1 January 1997 in our study therefore lead to inclusion of women who had not reached menopause, but ensured inclusion of all women that were close to menopause, and we observed that approximately 20% of women aged 40–49 years at the time of MI were in fact receiving HRT (not shown). The results of the multivariable logistic regression analysis of factors associated with use of HRT at time of MI show some important differences between the HRT and the non-HRT group (Table 3). For instance, women in the HRT group were more likely to have undergone a previous PCI and use antihypertensive therapy such as β-adrenoceptor blockers and ACE inhibitors and they were less likely to use glucose-lowering medication. This uneven distribution of risk factors between the groups is likely to have influenced the individual prescription of HRT.

The preferred types of HRT differ between countries and in Denmark the use of combined conjugated equine oestrogen and medroxyprogesterone acetate has never been as common as in, for example, the US where both HERS and WHI studied the effects of these specific hormones. Indeed, only 0.3% of claimed prescriptions from 1997 to 2006 in our study were for conjugated equine oestrogen (data not shown) and a previous study found that the most widely used types of oestrogen and progestogen in Denmark were 17-β-oestradiol and norethisterone acetate [7]. Hysterectomy was associated with use of oral and transdermal oestrogen alone and with low use of cyclic and continuous combined oestrogen/progestogen in agreement with the notion that hysterectomized women do not need progestogen to prevent endometrial hyperplasia, but may need to be treated with oestrogen if they have also had their ovaries removed.

In our study most women used vaginal oestrogen. We recognize that although the guideline recommendation of HRT discontinuation does not differentiate between HRT formulations it was based on results with conjugated equine oestrogens, and it remains to be established whether different routes of administration and types of HRT carry different risks of MI, since no randomized study has addressed this issue in detail. In this context, however, a recent study of vaginal oestrogen administration found a fivefold increase in serum oestradiol and thus it seems unlikely that the effects of vaginal oestrogen are limited to the vagina [20]. The large proportion of women in this study using vaginal HRT and changing to vaginal oestrogen after MI might indicate awareness among prescribers of the potential cardiovascular risk associated with HRT after MI and a perception that in this situation vaginal oestrogen is safer than other routes of HRT administration. Currently, however, this perception is only supported by a recent observational study [19].

In the years following publication of the WHI results in 2002, we found that around 80% of the women alive 1 year after MI had claimed a new prescription for HRT. Earlier in the study period the percentages of continued HRT use were even higher, e.g. >87% in 2000 (not shown). The proportions of women who after MI received the same category of HRT they used at the time of MI were somewhat lower, i.e. 82.5% in 2000–2002 and 77.3% in 2003–2005. These proportions were influenced by the extensive use of vaginal oestrogen in our population (>40% in 2002–2005), and vaginal oestrogen was the only category of HRT that showed a decreasing discontinuation rate throughout the study period. There was therefore little apparent effect of the WHI and HERS study results on the overall HRT use at time of admission and overall HRT discontinuation rate after MI in our population compared with the rapid and drastic decline in the general use of HRT in Denmark, which more than halved during the same period [7]. In the year following publication of the WHI results, use of the WHI HRT regimens, i.e. oral continuous combined conjugated equine oestrogen and medroxyprogesterone acetate and conjugated equine oestrogen alone, dropped 66% and 33% in the US, respectively, and in an Australian survey 64% of women using HRT in 2002 subsequently discontinued HRT mostly in response to media reports of the WHI result [10, 21]. On the other hand, a recent study from the UK found that in women on long-term HRT who felt well-informed about the WHI results, only three out of 100 were willing to give up HRT [22].

There are several reasons why women may choose to continue HRT after MI and not follow the guideline recommendations for HRT discontinuation. First, women may continue for fear of recurrent menopausal symptoms as vasomotor symptoms are likely to reappear in approximately half of patients when HRT is discontinued and the women's perceived value of symptomatic relief with HRT may outweigh the potentially increased risk of adverse cardiovascular effects and breast cancer [23, 24]. Second, perceptions of the prescribing physicians are likely to influence the decision to stop or continue HRT. A recent survey among US and European gynaecologists, obstetricians and general practitioners experienced in treating women with climacteric symptoms found that 96% of physicians would prescribe HRT to themselves, spouse or family members, and 78% of the interviewed physicians considered that the recent negative media coverage of HRT was unjustified [25]. Similar results have been found in Scandinavia [26]. Third, a reason for continuing HRT could be that HRT may improve other less defined aspects of health, e.g. general quality of life, sleep, body aches and sexual function [27]. Finally, current MI care is highly specialized and involves complex pharmacological and invasive treatment, which may unintentionally diminish the attention of cardiologists to the patients' use of HRT, although Danish cardiologists in the same period followed other guidelines for post-MI medical management closely [17]. In view of the treatment complexity and acknowledging that discontinuation may result in additional patient discomfort, the women's usual HRT prescribers may be reluctant to address discontinuation of HRT following MI or they may expect that the treating cardiologists would have already done so if this was clinically important.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of our study is the complete and nationwide information about use of HRT, co-morbidities and concomitant pharmacotherapy. To our knowledge this study is the first to investigate the use of HRT in women with MI and the first to assess whether women discontinue HRT thereafter. The required registration by the Danish pharmacies and the reimbursement of medical expenses ensure that all social classes and women both in and out of the labour market are represented, thereby preventing selection bias. This is supported by the fact that a healthy user bias has not been found in a prior study of HRT in Denmark [28]. Moreover, we were able to study women of all age groups using all formulations of HRT available on the market, thereby truly reflecting clinical practice in 1997 to 2006. The study limitations are inherent to the observational nature of the study. There may be unmeasured confounding and the HRT doses and treatment durations were calculated approximations. This means that the exact dates of beginning and ending a treatment may vary from the dates we have calculated. Also, we do not know the precise indications or contraindications for use of HRT and have no information about menopausal symptom severity, which may be a confounder since hot flashes may be a marker of increased cardiovascular risk [29]. Also, we lack clinical data on risk factors and the study does not account for geographic and ethnic variations in the use of HRT.

We used multivariable logistic regression to identify covariates associated with HRT use at time of MI, category of HRT, and discontinuation and change of HRT. This should be done with caution if the incidence of the outcome of interest in the study population is >10%, as it is in our population [30]. The more frequent the outcome, the more the odds ratio overestimates the risk ratio when it is more than 1 or underestimates it when it is less than 1. This means that the odds ratios in this study should not be interpreted as risk ratios, but instead should be interpreted as identifiers of whether or not an association is present.

In conclusion, in contrast to current treatment recommendations, we found that the majority of Danish women using HRT at the time of MI continue HRT thereafter. If HRT discontinuation is found to be impossible in these women after careful consideration, we believe that they should be advised to continue HRT for the shortest possible period of time and at the lowest possible doses [31]. There are currently no results from randomized clinical trials on the relative risks of different HRT regimens, although recent data have indicated higher risk of first-time MI with oral continuous combined treatment as compared with other HRT regimens [19]. Whether the same risk profile of HRT regimens exists in the post-MI setting is unknown. We conclude that a majority of Danish women experiencing an MI during ongoing HRT continue HRT after discharge. The HRT treatment pattern in the MI setting did not change markedly after pivotal randomized trials showed increased risk of coronary artery disease and other complications with HRT.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge The Lundbeck Foundation, Denmark (No. R31-A2566) and The Danish Heart Foundation; Denmark (No. 08-4-R65-A1904-B844-22440F).

Dr Gislason has a research fellowship from the Danish Agency for Science, Technology and Innovation, Denmark (No. 271-08-0944).

Competing interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE, Joffe M, Rosner B, Fuchs C, Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and mortality. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1769–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706193362501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, Furberg C, Herrington D, Riggs B, Vittinghoff E. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosca L, Banka CL, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bushnell C, Dolor RJ, Ganiats TG, Gomes AS, Gornik HL, Gracia C, Gulati M, Haan CK, Judelson DR, Keenan N, Kelepouris E, Michos ED, Newby LK, Oparil S, Ouyang P, Oz MC, Petitti D, Pinn VW, Redberg RF, Scott R, Sherif K, Smith SC, Jr, Sopko G, Steinhorn RH, Stone NJ, Taubert KA, Todd BA, Urbina E, Wenger NK. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115:1481–501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE, Jr, Chavey WE, 2nd, Fesmire FM, Hochman JS, Levin TN, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Wright RS, Smith SC, Jr, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Hunt SA, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lytle BW, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons: endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Circulation. 2007;116:e148–304. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amended report from the NAMS Advisory Panel on Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy. Menopause. 2003;10:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lokkegaard E, Lidegaard O, Moller LN, Agger C, Andreasen AH, Jorgensen T. Hormone replacement therapy in Denmark, 1995–2004. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:1342–51. doi: 10.1080/00016340701505523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guay MP, Dragomir A, Pilon D, Moride Y, Perreault S. Changes in pattern of use, clinical characteristics and persistence rate of hormone replacement therapy among postmenopausal women after the WHI publication. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:17–27. doi: 10.1002/pds.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mishra G, Kok H, Ecob R, Cooper R, Hardy R, Kuh D. Cessation of hormone replacement therapy after reports of adverse findings from randomized controlled trials: evidence from a British Birth Cohort. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1219–25. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hersh AL, Stefanick ML, Stafford RS. National use of postmenopausal hormone therapy: annual trends and response to recent evidence. JAMA. 2004;291:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Available at http://www.nordclass.uu.se/index_e.htm (last assessed April 2010)

- 12.Gaist D, Sorensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish prescription registries. Dan Med Bull. 1997;44:445–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madsen M, Davidsen M, Rasmussen S, Abildstrom SZ, Osler M. The validity of the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction in routine statistics: a comparison of mortality and hospital discharge data with the Danish MONICA registry. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:124–30. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tu JV, Austin PC, Walld R, Roos L, Agras J, McDonald KM. Development and validation of the Ontario acute myocardial infarction mortality prediction rules. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:992–7. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vermeulen MJ, Tu JV, Schull MJ. ICD-10 adaptations of the Ontario acute myocardial infarction mortality prediction rules performed as well as the original versions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:971–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumler T, Gislason GH, Kirk V, Bay M, Nielsen OW, Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C. Accuracy of a heart failure diagnosis in administrative registers. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:658–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ, Gadsboll N, Buch P, Friberg J, Rasmussen S, Kober L, Stender S, Madsen M, Torp-Pedersen C. Long-term compliance with beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins after acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1153–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thurston RC, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Everson-Rose SA, Hess R, Matthews KA. Hot flashes and subclinical cardiovascular disease: findings from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;118:1234–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.776823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lokkegaard E, Andreasen AH, Jacobsen RK, Nielsen LH, Agger C, Lidegaard O. Hormone therapy and risk of myocardial infarction: a national register study. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2660–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labrie F, Cusan L, Gomez JL, Cote I, Berube R, Belanger P, Martel C, Labrie C. Effect of one-week treatment with vaginal estrogen preparations on serum estrogen levels in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2009;16:30–6. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31817b6132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacLennan AH, Taylor AW, Wilson DH. Hormone therapy use after the Women's Health Initiative. Climacteric. 2004;7:138–42. doi: 10.1080/13697130410001713733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horner E, Fleming J, Studd J. A study of women on long-term hormone replacement therapy and their attitude to suggested cessation. Climacteric. 2006;9:459–63. doi: 10.1080/13697130601024629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Utian WH, Archer DF, Bachmann GA, Gallagher C, Grodstein F, Heiman JR, Henderson VW, Hodis HN, Karas RH, Lobo RA, Manson JE, Reid RL, Schmidt PJ, Stuenkel CA. Estrogen and progestogen use in postmenopausal women: July 2008 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2008;15:584–602. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31817b076a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grady D, Sawaya GF. Discontinuation of postmenopausal hormone therapy. Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 12B):163–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birkhauser MH, Reinecke I. Current trends in hormone replacement therapy: perceptions and usage. Climacteric. 2008;11:192–200. doi: 10.1080/13697130802060455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen AT, Iversen OE, Lokkegaard E, Mattsson LA, Milsom I, Nilsen ST, Ottesen B, Moen MH. Impact of recent studies on attitudes and use of hormone therapy among Scandinavian gynaecologists. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:1490–5. doi: 10.1080/00016340701745418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welton AJ, Vickers MR, Kim J, Ford D, Lawton BA, MacLennan AH, Meredith SK, Martin J, Meade TW. Health related quality of life after combined hormone replacement therapy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a1190. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lokkegaard E, Pedersen AT, Heitmann BL, Jovanovic Z, Keiding N, Hundrup YA, Obel EB, Ottesen B. Relation between hormone replacement therapy and ischaemic heart disease in women: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2003;326:426. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7386.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorodeski EZ. Are hot flashes linked to cardiovascular risk? It is too early to tell. Menopause. 2010;17:443–4. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181d0edaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. 1998/12/01 Edition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grady D, Barrett-Connor E. Postmenopausal hormone therapy. BMJ. 2007;334:860–1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39188.594282.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]