Abstract

Background

The introduction of new technology has increased the hospital cost of THA. Considering the impending epidemic of hip osteoarthritis in the United States, the projections of THA prevalence, and national cost-containment initiatives, we are concerned about the decreasing economic feasibility of hospitals providing THA.

Questions/purposes

We compared the hospital cost, reimbursement, and profit/loss of THA over the 1990 to 2008 time period.

Methods

We reviewed the hospital accounting records of 104 patients in 1990 and 269 patients in 2008 who underwent a unilateral primary THA. Hospital revenue, hospital expenses, and hospital profit (loss) for THA were evaluated and compared in 1990, 1995, and 2008.

Results

From 1990 to 2008, hospital payment for primary THA increased 29% in actual dollars, whereas inflation increased 58%. Lahey Clinic converted a $3848 loss per case on Medicare fee for service, primary THA in 1990 to a $2486 profit per case in 1995 to a $2359 profit per case in 2008. This improvement was associated with a decrease in inflation-adjusted revenue from 1995 to 2008 and implementation of cost control programs that reduced hospital expenses. Reduction of length of stay and implant costs were the most important drivers of expense reduction. In addition, the managed Medicare patient subgroup reported a per case profit of only $650 in 2008.

Conclusions

If hospital revenue for THA decreases to managed Medicare levels, it will be difficult to make a profit on THA. The use of technologic enhancements for THA add to the cost problem in this era of healthcare reform. Hospitals and surgeons should collaborate to deliver THA at a profit so it will be available to all patients. Government healthcare administrators and health insurance payers should provide adequate reimbursement for hospitals and surgeons to continue delivery of high-quality THAs.

Level of Evidence

Level III, economic and decision analysis. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

The prevalence of THA in the United States increased each year between 1990 and 2008, and demand for primary THA is projected to grow to 572,000 procedures by 2030 [9]. However, although demand for THA increased, Medicare hospital payment for primary THA increased only 29% (actual dollars; $8500 in 1990 and $11,080 in 2008) [13]. During this 18-year time interval, the rate of inflation was 58%, or double the increase in reimbursement [17]. In the 1990s, hospital expenses were controlled through utilization review, decreased length of stay, and implant cost reduction programs [6–8]. Increased labor costs and the cost of technology introduction in the new millennium threaten to offset the control of hospital expenses achieved in the 1990 s. The decreased relative revenue, coupled with rising hospital expenses for THA, presents a serious challenge for a hospital and its ability to break even or profit on THA.

The use of alternative bearing surfaces such as highly crosslinked polyethylene, highly polished metals, and ceramics has increased considerably over the past decade, especially in the younger, more active patient population. These materials may offer clinical advantages, but they are expensive, and alternative bearing surfaces contribute to rising costs for THA. Advocates for these bearing surfaces state they offer the potential for reduced implant failures secondary to decreased bearing surface wear [16]. However, evidence of improved long-term clinical outcomes in terms of superior implant survival has not yet been demonstrated [5].

We compared the hospital economics of primary THA at Lahey Clinic from 1990 to 2008. The differences in reimbursement by health insurance payers were analyzed. Hospital expenses were analyzed to determine if the cost associated with hospital service centers had changed from 1990 to 2008. Finally, we determined whether the use of alternative bearing surfaces alter a hospital’s ability to profit or break even for THA.

Patients and Methods

We reviewed the hospital accounting records of 104 patients in 1990 and 269 patients in 2008 who underwent a unilateral primary THA. In 2008, 282 patients underwent primary THA at Lahey Clinic. Patients who had femoral head resurfacing, bilateral THA, revision THA, complications related to THA, and a secondary operative procedure during the same hospitalization were excluded from the study. Patients for whom there were insufficient billing data were excluded (Table 1). For 2008, we excluded 13 patients because they were part of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) MS-DRG 469 (major joint replacement of lower extremity with major comorbidities). This group has a reimbursement for THA different from that of MS-DRG 470 (major joint replacement of lower extremity without major comorbidities) (Table 1). The exclusions left 269 patients for 2008.

Table 1.

THA demographics

| Variable | 1990 | 2008 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicare only | All patients | Medicare only | Managed Medicare | Major private health plans | Other | |

| Primary unilateral THA | 104 | 282 | 122 | 42 | 78 | 40 |

| Without major comorbidities | 269 (95%) | 115 (94%) | 38 (94.8%) | 76 (98.9%) | 40 (94.1%) | |

| With major comorbidities | 13 (5%) | 7 (6%) | 4 (5.2%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0 (5.9%) | |

| Study patients | 104 | 269 | 115 | 38 | 76 | 40 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Median | 68 | 69 | 76 | 76 | 60 | 56 |

| Range | 53–87 | 18–93 | 42–93 | 66–89 | 18–89 | 18–91 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Osteoarthritis | 85 (82%) | 237 (88%) | 101 (87%) | 34 (90%) | 71 (93%) | 31 (78%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3 (3%) | 7 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (5%) |

| Osteonecrosis | 5 (5%) | 12 (5%) | 3 (3%) | 3 (7%) | 2 (3%) | 4 (10%) |

| Other | 11 (10%) | 13 (5%) | 8 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (8%) |

| Operating surgeons | 2 | 6 | ||||

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | 9.3 | 4.09 | 3.83 | 3.86 | 4.29 | 4.73 |

The average age of the 104 study patients in 1990 was 68 years (range, 53–87 years). The primary diagnosis was osteoarthritis for 85 patients (82%), rheumatoid arthritis for three patients (3%), osteonecrosis for five patients (5%), and other for 11 patients (10%). The average age of the 269 study patients in 2008 was 69 years (range, 18–93 years). The primary diagnosis was osteoarthritis for 237 patients (88%), rheumatoid arthritis for seven patients (2%), osteonecrosis for 12 patients (5%), and other for 13 patients (5%) (Table 1).

All patients had a primary THA at Lahey Clinic. Two surgeons performed the operations in 1990, and six surgeons (including the previous two surgeons) performed the operations in 2008. From 1995 to the present, the management of all patients undergoing THA was standardized according to a clinical pathway [6–8]. All procedures involved arthroplasty of both the acetabulum and femur. The average hospital stay was 9.3 days in 1990 and 4.1 days in 2008 (Table 1).

Hospital revenue, hospital expenses, and hospital profit (loss) for THA were evaluated and compared in 1990, 1995, and 2008. To compare data from 1990 and 1995 with data from 2008, 1990, and 1995, US dollars were converted to inflation-adjusted 2008 US dollars with the consumer price index for all urban consumers obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics [16].

In 1990 and 1995, hospital revenue for THA for all 104 patients was provided through the Medicare DRG system administered by the Health Care Financing Administration (DRG-209; major joint replacement of lower extremity). In 2008, hospital revenue for THA for these 269 patients is reported in four payer categories: Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) (115), managed Medicare (38), major private health plans (76), and other payers (40). Hospital payment for Medicare FFS patients was provided through the Medicare MS-DRG system administered by CMS (MS-DRG 470; major joint replacement of lower extremity without major comorbidities).

Hospital expenses for THA were determined by different methods in 1990, 1995, and 2008. In 1990, hospital cost data were established using government-mandated, hospital-specific, cost-to-charge ratios. This method of determining hospital cost was generally accepted in 1990. In 1995 and 2008, a resource-based hospital accounting system (TSI Inc, Cambridge, MA) provided actual hospital cost data for each procedure. The 17 service center breakdown was not available for the 1995 cohort. Direct and indirect costs were assigned to hospital services based on cost data within the system.

In 1990, hospital expenses were allocated to six service centers. The major areas of comparison were the operating room, the hospital room, and supplies. Hospital expenses were allocated to 17 service centers in 2008 such as the laboratory, operating room (OR), or radiology department, for which charges and costs are available. The anesthesiology service center included operative anesthetics and the technical costs used for each case. The blood bank service center included blood type tests and transfusion costs. The electrocardiology service center included perioperative electrocardiograms. The hospital room service center included all hospital floor-related costs during a patient’s stay from nursing to meals to dressing change supplies. Intravenous therapy included intravenous and peripherally inserted central catheter placement costs. Daily phlebotomy draws and laboratory work such as complete blood count, international normalized ratio, and basic metabolic profile were included in the laboratory service center. The OR service center included staff and administrative expenses. The orthopaedic appliance service center included abduction pillows. Pathology included pathologic evaluation of OR specimens. The pharmacy service center included perioperative medications such as antibiotics, analgesics, anticoagulants, etc, administered during a patient’s hospital course. The initial physical therapy/occupational therapy (PT/OT) evaluation and daily gait training and therapeutic activities were all included in the PT/OT service center. Perioperative chest radiographs and postoperative hip radiographs were among the costs included in the radiology service center. The recovery room cost included staff and administrative expenses. Postoperative ventilatory support, continuous positive airway pressure, and pulse oximetry were included in the respiratory therapy service center. Supplies (medical and operative) included specific products with variable cost purchased by the hospital for THA. The cost of hip implants was included in this service center. Specific implant prices are not provided as a result of purchasing agreements with implant manufacturers. Noninvasive scans of the lower extremity to evaluate for thromboembolic disease accounted for the vascular laboratory service center. The other service center included miscellaneous services/testing performed postoperatively (Tables 2, 3).

Table 2.

Cost analysis

| Service center | Actual cost | Inflation-adjusted cost (2008 dollars) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2008 | Change from 1990 to 2008 | 1990 | Change from 1990 to 2008 | |

| Medicare only | All patients | All patients | Medicare only | All patients | |

| Anesthesiology | $514 | ||||

| Blood bank | $616 | ||||

| Electrocardiography | $12 | ||||

| Hospital room | $4541 | $3739 | −18% | $7480 | −50% |

| Intravenous therapy | $62 | ||||

| Laboratory | $249 | ||||

| Operating room | $2099 | $2267 | 8% | $3458 | −34% |

| Orthopaedic appliances | $1 | ||||

| Pathology | $13 | ||||

| Pharmacy | $104 | ||||

| Physical/occupational therapy | $371 | $406 | 10% | $610 | −33% |

| Radiology | $238 | ||||

| Recovery room | $494 | $894 | 81% | $814 | 10% |

| Respiratory therapy | $10 | ||||

| Supplies (medical and operative) | $2947 | $2506 | −15% | $4855 | −48% |

| Vascular laboratory | $3 | ||||

| Other | $1897 | $55 | |||

| Total hospital cost | $12,348 | $11,688 | −5% | $18,695 | −42% |

Table 3.

THA hospital expense allocation

| Service center | Allocation of hospital cost for THA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2008 | Change from 1990 to 2008 | |

| Anesthesiology | 4.40% | ||

| Blood bank | 5.27% | ||

| Electrocardiography | 0.11% | ||

| Hospital room | 36.78% | 31.99% | −4.78% |

| Intravenous therapy | 0.53% | ||

| Laboratory | 2.13% | ||

| Operating room | 17.00% | 19.39% | 2.40% |

| Orthopaedic appliances | 0.01% | ||

| Pathology | 0.11% | ||

| Pharmacy | 0.89% | ||

| Physical/occupational therapy | 3.00% | 3.48% | 0.48% |

| Radiology | 2.03% | ||

| Recovery room | 4.00% | 7.65% | 3.65%– |

| Respiratory therapy | 0.08% | ||

| Supplies (medical and operative) | 23.87% | 21.44% | −2.43% |

| Vascular laboratory | 0.03% | ||

| Other | 15.36% | 0.47% | −14.90% |

Results

In 1990, hospital revenue per case for 104 primary THAs was $8500 in actual cost dollars and $14,002 in inflation-adjusted dollars. In 1995, hospital revenue per case was $13,590 in actual dollars and $19,199 in inflation-adjusted dollars. In 2008, hospital revenue for 269 primary THAs was $15,789 per case (Table 4). From 1990 to 1995, hospital revenue per case for primary THA increased 60% in actual dollars. However, from 1995 to 2008, hospital revenue per case increased only 16% in actual dollars, whereas it decreased 18% in inflation-adjusted dollars. During this period, inflation increased 37% (Table 4). In 1990, hospital cost per case was $12,348 in actual dollars and $20,341 in inflation-adjusted dollars. In 1995, hospital expense per case was $11,104 in actual dollars and $15,687 in inflation-adjusted dollars. In 2008, hospital expense per case was $11,688 (Table 4).

Table 4.

THA hospital revenue/expense/profit (loss) data

| Variable | 1990 | 1995 | 2008 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients Medicare Only | All patients Medicare Only | All patients | Medicare FFS only | Managed Medicare | Major private health plans | Other | |||

| $(1990) | $(2008) | $(1995) | $(2008) | $(2008) | $(2008) | $(2008) | $(2008) | $(2008) | |

| Number of patients | 104 | 269 | 115 | 38 | 76 | 40 | |||

| Total hospital revenue | $884,000 | $1,456,213 | $4,247,322 | $1,613,761 | $433,382 | $1,496,898 | $502,602 | ||

| Base payment | $884,000 | $1,456,213 | $3,691,595 | $1,258,713 | $433,382 | $1,496,898 | $502,602 | ||

| IME payment | $363,640 | $232,325 | |||||||

| Capital payment | $192,087 | $122,722 | |||||||

| Hospital revenue per case | $8500 | $14,002 | $13,590 | $19,199 | $15,789 | $14,033 | $11,405 | $19,696 | $12,565 |

| Base payment per case | $8500 | $14,002 | $13,590 | $19,199 | $13,723 | $10,945 | $11,405 | $19,696 | $12,565 |

| IME payment per case | $1352 | $2020 | |||||||

| Capital payment per case | $714 | $1067 | |||||||

| Hospital expense | $1,284,192 | $2,115,449 | $3,144,145 | $1,342,540 | $408,679 | $855,802 | $537,119 | ||

| Hospital expense per case | $12,348 | $20,341 | $11,104 | $15,687 | $11,688 | $11,674 | $10,755 | $11,261 | $13,428 |

| Hospital profit (loss) | ($400,192) | ($659,236) | $1,103,177 | $271,221 | $24,703 | $641,096 | ($34,517) | ||

| Hospital profit (loss) per case | ($3848) | ($6339) | $2486 | $3512 | $4101 | $2358 | $650 | $8435 | ($863) |

| Without IME payment | $2749 | $338 | $650 | $8435 | ($863) | ||||

| Without IME + capital payment | $2035 | ($729) | $650 | $8435 | ($863) | ||||

FFS = fee for service; IME = indirect medical education.

From 1990 to 1995, hospital expense per case for primary THA decreased 10% in actual dollars and decreased 23% in inflation-adjusted dollars. From 1995 to 2008, hospital expense per case for primary THA increased 5% in actual dollars and decreased 25% in inflation-adjusted dollars (Table 4). Primary THA at Lahey Clinic was not profitable in 1990. The hospital lost $3848 per case in actual dollars. The hospital lost $6339 per case in inflation-adjusted dollars. In contrast, in 1995, the hospital earned $2486 per case for THA in the Medicare subgroup. However, this increase in profit did not continue from 1995 to 2008 in the Medicare subgroup. In 2008, the hospital earned $4101 per case for all THAs. In 2008, when looking at Medicare FFS patients (115 of 269 patients), the hospital earned $2358 per case. Additionally, when looking at the managed Medicare patients (38 of 269 patients) in 2008, the hospital earned only $650 per case (Table 4). Major private payer insurers were the most profitable subgroup in 2008, $8,435 per case; however, this subgroup (76 of 269 [28.2%]) is made up of a small number of the youngest, most active patients who may be candidates for alternative bearing surfaces and other newer technologic innovations. At Lahey Clinic in 2008, all patients received implants at one price under a single price/case price purchasing program [6], which minimized the impact of new technology on the cost of implants and preserved the hospital profits in this non-Medicare subgroup (Table 4).

When hospital expenses were allocated to the 17 service centers, the hospital room, OR, and supplies (medical and operative) service centers represented the largest percentage of hospital expense. These three service centers accounted for 77.6% of hospital cost in 1990 and 72.8% in 2008. The hospital room service center accounted for $4541 (36.8%) in 1990 and $3739 (32.0%) in 2008, a decrease of 5% in actual dollars (Tables 2, 3). The reduction in cost for the hospital room service center was associated with the reduction in length of stay. The OR service center for THA accounted for $2099 (17.0%) in 1990 and $2267 (19.4%) in 2008, an increase of 2.4% in actual dollars (Tables 2, 3, 5).The supplies (medical and operative) service center for THA accounted for $2947 (23.9%) in 1990 and $2506 (21.4%) in 2008, a decrease of 2.4% in actual dollars. The reduction in cost for the supplies service center was associated with reduction of hip implant cost (Tables 2–4).

Table 5.

THA economic trends from 1990 to 2008

| Year | Actual dollars | Inflation-adjusted dollars | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | Expense | Profit | Revenue | Expense | Profit | |

| 1990 (Medicare only) | $8500 | $12,348 | −$3848 | $14,002 | $20,341 | −$6339 |

| 1995 [6] (Medicare only) | $13,590 | $11,104 | $2486 | $19,199 | $15,687 | $3512 |

| 1996 [7] (All patients) | $13,446 | $9600 | $3846 | $18,451 | $13,173 | $5278 |

| 2004 [10] (All patients) | $12,769 | $9855 | $2914 | $14,554 | $11,232 | $3321 |

| 2007 [11] (All patients) | $14,305 | $11,445 | $2860 | $14,854 | $11,884 | $2969 |

| 2008 (All patients) | $15,789 | $11,688 | $4101 | $15,789 | $11,688 | $4101 |

| 2008 (Medicare FFS patients) | $14,033 | $11,674 | $2359 | $14,033 | $11,674 | $2359 |

| 2008 (managed Medicare patients) | $11,405 | $10,755 | $650 | $11,405 | $10,755 | $650 |

FFS = fee for service.

Our economic results for THA for 38 managed Medicare patients presented an unfavorable comparison with our Medicare FFS patients. Hospital revenue per case was 19% less ($11,405 versus $14,003); hospital expense per case was similar ($10,755 versus $11,674); and hospital profitability per case was 72% less ($650 versus $2,358) than Medicare FFS patients in 2008. The primary reason for less profitability among managed Medicare patients is less revenue per case. Lahey Clinic did not receive an indirect medical education (IME) payment or a capital expense payment for managed Medicare patients.

Discussion

Hospital reimbursement for THA has lagged behind inflation, and expenses have increased primarily as a result of increased labor costs and increased implant costs. This trend is concerning; given the increasing prevalence of THA, which is projected to grow to 572,000 procedures by 2030 [10]. It has been reported that some hospitals cannot make a profit when delivering medical and surgical services with current Medicare payment schedules [9, 15]. We evaluated and compared the hospital economics of primary THA at Lahey Clinic in 1990, 1995, and 2008. In addition, we reviewed the use of alternative bearing surfaces and how their use alters a hospital’s ability to profit or break even for THA.

Our study is subject to certain limitations. First, our sample size was small in 1990 and was limited to the Medicare DRG cohort. The 1995 cohort also was limited to the Medicare DRG group. In the 2008 patient group, all insurers are reported and it has been broken out so that appropriate comparisons can be made with the prior patient groups. Second, the resource-based accounting system, which was used for the 2008 cohort service center breakdown, was not available in 1990 and was not archived for the 1995 cohort. The major service centers of comparison, however, OR, patient room, and supplies (surgical and medical), were supplied for the 2008 and 1990 cohorts. Third, patients in the MS-DRG 469 (major joint replacement of lower extremity with major comorbidity) were eliminated from this study to standardize the comparison with the cohort from 1990 where outliers had also been eliminated. Fourth, a strength and weakness of this study was that all operations were performed in one hospital, by one group of surgeons within one group practice, using a standardized clinical pathway and all implants were purchased from one vendor in each year studied. All surgeons were salaried employees of Lahey Clinic and had an interest in preserving the economic health of their hospital. This is a distinct difference from private hospitals where surgeons are not salaried members of the staff and have less incentive to work with their hospitals to control the hospital cost of THA. The major strength of this study is the quality of the data from the Lahey Clinic Finance Department. The resource-based accounting system reported actual cost data for 17 service centers and enabled us to report where the expenses had increased and decreased over an 18-year examination of hospital costs.

In response to the losses on THA operation in 1990, orthopaedic surgeons and administrators at Lahey Clinic [6–8] developed and implemented several cost control strategies for THA. The efficacy of these strategies can be seen in 1995 when the hospital earned a profit of $2486 per case for Medicare FFS THA patients. However, this increase in profitability did not continue from 1995 to 2008 and profit decreased 5% in actual dollars from $2486 to $2358 and by 33% in inflation-adjusted dollars from $3512 to $2358 for Medicare FFS patients. Between 1990 and 2008, Lahey Clinic converted a $3848 loss per case for all primary THA operations into a $4101 profit per case when all payers were considered. That is the good news. However, when looking at the time period between 1995 and 2008 and examining the Medicare FFS patients, a different trend is noted. Hospital revenue in actual dollars increased only 3% ($13,590 to $14,033), hospital revenue in inflation-adjusted dollars decreased 27% ($19,199 to $14,033), and hospital profit has decreased 5.1% ($2486 to $2358) in actual dollars and decreased 32.8% ($3512 to $2358) in inflation-adjusted dollars.

Lahey Clinic is a teaching hospital and therefore receives IME payments for Medicare FFS patients. In 2008, if Lahey Clinic were not a teaching hospital, hospital revenue for THA would have been $1352 (33%) less per case for all patients and $2020 (86%) less per case for Medicare FFS patients (Table 4). All hospitals receive capital expense payments for Medicare FFS patients; however, all hospitals do not include capital expense payments in their hospital revenue for services. In 2008, if Lahey Clinic did not include capital payments, hospital revenue per case for THA would have been $714 (17%) less for all patients and $1067 (45%) less for Medicare FFS patients (Table 4). Managed Medicare hospital profit for primary THA was 84% less per case. In a healthcare environment with increasing demand for THA, decreasing hospital reimbursement, and increasing labor and supply expenses, this current dynamic is unsustainable.

Evaluations of hospital economics for THA should include a discussion of alternative joint bearing surfaces. Several studies have suggested alternative bearing surfaces reduce wear rates [1, 3, 4]. However, there are no studies demonstrating the long-term clinical benefits from these bearing surfaces [5]. Bozic et al. [2] evaluated the theoretical benefits of alternative bearing surfaces and found the cost-effectiveness of their use is highly dependent on the age of the patient at the time of surgery, the cost of the implant, and the associated reduction in the probability of revision relative to conventional bearing surfaces. Prior studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of new technologies for use in THA. Vale et al. [18] used clinical effectiveness data and cost data to estimate the cost-effectiveness of metal-on-metal resurfacing for treating patients 65 years and older. The authors concluded metal-on-metal resurfacing could be cost-effective versus conventional THA if revision rates were 20% lower.

In 2008, the market share of alternative bearings was 27% with metal-on-metal accounting for 24% of the market and ceramic-on-ceramic accounting for 3% of the market [13]. For 2008, if the average selling price of a ceramic-on-ceramic hip implant of $7754 was substituted for all patients, Lahey Clinic would have lost $1147 per patient [13, 14]. For Medicare FFS patients, Lahey Clinic would have lost $1971 and for managed Medicare patients, Lahey Clinic would have lost $4599. If the 2008 average selling price of a metal-on-metal hip implant of $7141 was substituted for all patients, Lahey Clinic would have lost $534 per patient.

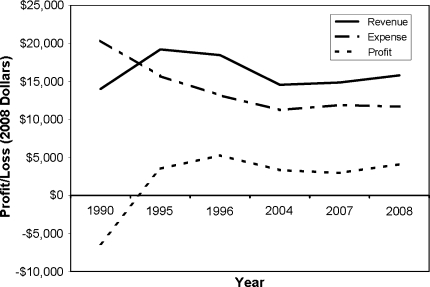

To better understand the trend of hospital economic results for THA, we examined our revenue, expense, and profit (loss) at six time points from 1990 to 2008. All the information is from our hospital [7, 8, 11, 12] (Fig. 1). In inflation-adjusted dollars, comparing Medicare FFS patients, hospital profit increased from 1990 to 1996 and then decreased from 1996 to 2008. In inflation-adjusted dollars, hospital expense for THA decreased from 1990 to 2008. Hospital cost has been actively managed since the early 1990s and facilitated the increase in profit between 1990 and 1995. However, despite effective cost control strategies, our hospital profit for THA peaked with hospital revenue in 1996, and profit decreased from 1996 to 2008 in inflation-adjusted dollars.

Fig. 1.

A graph shows Lahey Clinic THA economic trends from 1990 to 2008.

If hospital revenue for THA decreases to managed Medicare levels, it will be difficult to make a profit on THA. To maintain access for our patients, hospitals and surgeons should collaborate to deliver THA at a profit so it will be available to all patients with painful arthritic hips. Government healthcare administrators and health insurance payers should provide adequate reimbursement for hospitals and surgeons to continue the delivery of high-quality THAs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christopher Lucchesi, Lahey Clinic Finance, and John Garfi, Orthopaedic Clinical Research Specialist, who made valuable contributions to this project.

Footnotes

One of the authors (WLH) has a product development agreement with DePuy Orthopaedics, Inc (Warsaw, IN).

References

- 1.Anissian HL, Stark A, Gustafson A, Good V, Clarke IC. Metal-on-metal bearing in hip prosthesis generates 100-fold less wear debris than metal-on-polyethylene. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70:578–582. doi: 10.3109/17453679908997845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bozic KJ, Morshed S, Silverstein MD, Rubash HE, Kahn JG. Use of cost-effectiveness analysis to evaluate new technologies in orthopaedics: the case of alternative bearing surfaces in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:706–714. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Antonio J, Capello W, Manley M. Alumina ceramic bearings for total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2003;26:39–46. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20030101-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Digas G, Karrholm J, Thanner J, Malchau H, Herberts P. Highly cross-linked polyethylene in cemented THA: randomized study of 61 hips. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;417:126–138. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000096802.78689.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumbleton JH, Manley MT. Metal-on-metal total hip replacement: what does the literature say? J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:174–188. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healy WL, Iorio R, Lemos MJ, Patch DA, Pfeifer BA, Smiley PM, Wilk RM. Single price/case price purchasing in orthopaedic surgery: experience at the Lahey Clinic. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:607–612. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200005000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healy WL, Iorio R, Richards JA. Comparison of the hospital cost of primary and revision total hip arthroplasty after cost containment. Orthopedics. 1999;22:185–189. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19990201-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Healy WL, Iorio R, Richards JA, Lucchesi C. Opportunities for control of hospital costs for total joint arthroplasty after initial cost containment. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:504–507. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(98)90048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacoby J. Medicare and the Mayo Clinic. Boston Globe. January 6, 2010.

- 10.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lahey Clinic Finance. Total Joint Arthroplasty Margin Analysis, 2004. Burlington, MA: Lahey Clinic; 2004.

- 12.Lahey Clinic Finance. Total Joint Arthroplasty Margin Analysis, 2007. Burlington, MA: Lahey Clinic; 2007.

- 13.Mendenhall S. Hip and knee implants list prices rise 5.6% Orthop Network News. 2009;20:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendenhall, S. Hospital resources and implant cost management—a 2008 update. Orthop Network News. 2009;20:17.

- 15.Olmos D. Mayo Clinic in Arizona to stop treating some Medicare patients. December 31, 2009. Available at: www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?p…d=aHoYSI84VdL0. Accessed March 17, 2010.

- 16.Santavirta S, Bohler M, Harris WH, Konttinen YT, Lappalainen R, Muratoglu O, Rieker C, Salzer M. Alternative materials to improve total hip replacement tribology. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:380–388. doi: 10.1080/00016470310017668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. CPI inflation calculator. Available at: www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed March 17, 2010.

- 18.Vale L, Wyness L, McCormack K, McKenzie L, Brazzelli M, Stearns SC. A systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty for treatment of hip disease. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6:1–109. doi: 10.3310/hta6150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]