Abstract

Background

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) provides high functional scores and long-term survivorship. However, differences in function and disability between men and women before and after arthroplasty are not well understood.

Questions/purposes

We determined if there was a gender difference in patient-perceived functional measures and range of motion in primary THA.

Methods

We retrospectively studied 532 patients (658 hips) undergoing primary THA. A total of 59% were women and 41% were men. Patients were assessed preoperatively and at minimum 2 years using Quality of Well-being, SF-36, WOMAC, and Harris hip score. We determined if differences existed between genders before and at followup for all dependent measures. Independent t-tests were also used to determine differences between genders concerning the change (Δ) scores and hip range of motion. The time course of perceived functional recovery was also documented.

Results

Males were on average 5 years (58) younger than females (63). Before surgery, females scored worse than males on the Harris hip score, WOMAC function, WOMAC pain, and WOMAC total scores. All scores improved at followup in both groups. Regardless of time, females had lower scores than males. However, females had greater improvement over males for WOMAC function (39 versus 35), WOMAC pain (11 versus 10), and WOMAC total (53 versus 48).

Conclusions

Substantial gender functional differences exist before treatment. However, women reported greater improvement as a result of the intervention when compared with men.

Level of Evidence

Level III, prognostic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis is among the most prevalent chronic conditions and leading causes of long-term disability among the elderly [9]. The prevalence of osteoarthritis-related disability is greater among women than among men [28]. Arthritis is a major health problem for women. Joint arthroplasty is a viable treatment for advanced arthritis of the hip and knee that relieves pain and reduces functional disability [5].

The effect of patient-related factors on outcomes after hip arthroplasty remains unclear [26]. In 2005, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the National Institute of Health stressed the importance of achieving a better understanding of the role of gender in orthopaedic treatments and outcomes [31].

We therefore (1) compared perceived measures of well-being, function, and pain between females and males before THA and on average 5 years; (2) compared the improvement in perceived measures of well-being, function, pain, and ROM between females and males at followup; and (3) determined the time course of perceived functional recovery in females and males by presenting the results graphically over time.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively reviewed prospectively collected data on 568 patients (693 hips) with primary or secondary osteoarthritis who underwent primary THA performed from April 1993 to March 2007. Twenty-seven patients (27 THAs) did not complete the preoperative evaluation and therefore were excluded from the study. Nine patients (nine THAs) were lost to followup. Five hundred thirty-two patients (658 hips) were included in the study. Sociodemographic information was obtained from questionnaires administered to patients at their first office visit and at their preoperative evaluation. The average age of the cohort was 61 ± 15 years (mean ± SD). Of the total number of patients, 316 (59%) were females and 216 were male. Females were older than males (64 ± 14, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 62–66 years versus 59 ± 16, 95% CI: 57–62, respectively). Females had a lower Charlson score [7] (0.8 ± 1.2, 95% CI 0.6–0.9) compared with males (1.2 ± 1.6; 95% CI: 0.2–1.4, respectively). Females had a lower body mass index (weight [kg]/height [m2]) compared with males (28 ± 7, 95% CI: 27–29 versus 30 ± 6, 95% CI: 28–31, respectively). The minimum followup was 2 years (mean, 5.6 years; range, 2–16 years). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained before starting this study and all patients gave written consent.

Perioperative antibiotics were used for prophylaxis, and a standard protocol of postoperative warfarin was used for thromboembolism prophylaxis.

All surgeries were performed by a single surgeon (CJL). The surgical technique used in all cases was a modified direct lateral approach (Hardinge). All patients received a tapered stem and a press-fit technique was used for the femoral and the acetabular components. Screws were used in the acetabular component for supplemental fixation in all patients. Full weightbearing was permitted as tolerated on postoperative Day 1. An abduction pillow was indicated at all times whenever in bed.

Physical therapy was initiated in the afternoon if the patient was operated on in the morning or the next day if the patient was operated on after midday. Physical therapy was supervised by a licensed professional and patients received treatments two times per day on 30-minute sessions as tolerated. Physical therapy consisted of transfer training, gait training with the use of a standard walker, bed mobility education, and general therapeutic exercises such as ROM and manual resistive exercises. Most patients were discharged to home within 3 to 4 days in the absence of complications.

All followup tests were completed at 1-year intervals. We studied preoperative and postoperative outcomes using the Quality of Well-being [14, 15], SF-36 [1, 22], WOMAC [3], Harris hip score [12, 23], and Merle d’Aubigné-Postel [11]. ROM was assessed using a standard handheld goniometer for hip abduction, adduction, flexion, and internal and external rotation.

A multivariate analysis of covariance was used to determine if differences existed between genders before and at followup for all dependent measures. Age and body mass index were used as covariates in the model. Independent t-tests were used to determine differences between genders concerning the change (Δ) scores from before surgery to followup for each dependent measure. Independent t-tests were also used to determine differences between genders for ROM assessments before and after surgery. We created four time intervals based on postoperative followup so we could visually present the time course of perceived recovery of well-being, pain, and physical function in both females and males. The four time intervals were 2 to 3 years, 4 to 5 years, 6 to 7 years, and 8 years and longer. Although not part of our initial intent, we compared length of hospital stay between genders using an independent t-test. A phi coefficient was used to determine the association between gender and type of complication. The Patient Analysis and Tracking System (V6.0; Portland, OR) was used to maintain the joint registry of all data. Excel (Microsoft Office 2007; Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) was used to create initial statistical spreadsheets and SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

Before surgery, females presented with worse scores for all dependent measures (Table 1). By postoperative followup, there was no difference between females and males for all dependent measures (Table 2). Pertaining to change scores, females had greater change in WOMAC physical function, pain, and stiffness dimensions (Table 3). Before surgery, there was no difference between genders for all ranges assessed (Table 4). However, females presented with greater hip abduction and internal rotation ROM by postoperative followup (Table 5).

Table 1.

Preoperative outcome measures for gender

| Outcome measures | Gender | Mean ± SD | p | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| QWB | F | 0.516 ± 0.05 | < 0.0001 | 0.509 | 0.524 |

| M | 0.539 ± 0.05 | 0.529 | 0.548 | ||

| SF-36 Physical Function | F | 14.2 ± 17.7 | < 0.0001 | 11.97 | 16.53 |

| M | 23.1 ± 20.7 | 19.76 | 26.48 | ||

| SF-36 Bodily Pain | F | 31.3 ± 21.5 | < 0.0001 | 28.56 | 34.11 |

| M | 38.6 ± 21.4 | 35.13 | 42.07 | ||

| SF-36 Social Function | F | 42.5 ± 33.4 | 0.001 | 38.24 | 46.84 |

| M | 53.7 ± 31.2 | 48.69 | 58.8 | ||

| SF-36 Physical Component | F | 25.7 ± 7.39 | 0.001 | 24.79 | 26.7 |

| M | 28.3 ± 7.21 | 27.15 | 29.49 | ||

| WOMAC Function | F | 46.5 ± 12.7 | < 0.0001 | 44.94 | 48.23 |

| M | 41.9 ± 11.6 | 40.03 | 43.8 | ||

| WOMAC Pain | F | 12.5 ± 4.17 | 0.001 | 12.02 | 13.1 |

| M | 11.2 ± 3.65 | 10.62 | 11.8 | ||

| WOMAC Stiffness | F | 3.81 ± 2.46 | 0.038 | 3.49 | 4.13 |

| M | 3.34 ± 2.41 | 2.95 | 3.73 | ||

| Harris hip score | F | 36.5 ± 14.8 | 0.02 | 34.68 | 38.5 |

| M | 40.1 ± 14.4 | 37.73 | 42.41 | ||

| Postel D’Abigne hip score | F | 9.37 ± 3.05 | 0.001 | 8.97 | 9.76 |

| M | 10.4 ± 3.03 | 9.93 | 10.91 | ||

QWB = Quality of Well-being; F = female; M = male.

Table 2.

Postoperative outcome measures for gender

| Outcome measures | Gender | Mean ± SD | p | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| QWB | F | 0.608 ± 0.11 | 0.99 | 0.595 | 0.621 |

| M | 0.611 ± 0.10 | 0.597 | 0.626 | ||

| SF-36 Physical Function | F | 53.6 ± 28.3 | 0.06 | 50.57 | 56.71 |

| M | 59.7 ± 27.1 | 56.04 | 63.39 | ||

| SF-36 Bodily Pain | F | 63.1 ± 27.9 | 0.12 | 60.16 | 66.2 |

| M | 67.0 ± 28.4 | 63.14 | 70.88 | ||

| SF-36 Social Function | F | 77.1 ± 26.8 | 0.37 | 74.27 | 80.07 |

| M | 79.2 ± 26.1 | 75.73 | 82.82 | ||

| SF-36 Physical Component | F | 40.8 ± 11.4 | 0.19 | 39.65 | 42.13 |

| M | 42.4 ± 10.9 | 40.95 | 43.93 | ||

| WOMAC Function | F | 8.24 ± 12.5 | 0.29 | 6.88 | 9.6 |

| M | 9.03 ± 12.9 | 7.28 | 10.79 | ||

| WOMAC Pain | F | 1.44 ± 3.19 | 0.41 | 1.09 | 1.78 |

| M | 1.90 ± 3.72 | 1.4 | 2.41 | ||

| WOMAC Stiffness | F | 0.62 ± 1.37 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.76 |

| M | 0.75 ± 1.40 | 0.56 | 0.94 | ||

| Harris hip score | F | 82.7 ± 13.3 | 0.24 | 81.29 | 84.18 |

| M | 84.3 ± 13.9 | 82.42 | 86.21 | ||

| Postel D’Aubigne hip score | F | 14.7 ± 4.51 | 0.66 | 14.28 | 15.25 |

| M | 14.4 ± 5.00 | 13.76 | 15.11 | ||

QWB = Quality of Well-being; F = female; M = male.

Table 3.

Delta change (Δ) score for all outcome measures for gender

| Outcome measures | Gender | Mean ± SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| QWB | F | 0.09 ± 0.12 | 0.47 |

| M | 0.09 ± 0.12 | ||

| SF-36 Physical Function | F | 40.0 ± 29.5 | 0.75 |

| M | 40.7 ± 27.8 | ||

| SF-36 Bodily Pain | F | 33.7 ± 33.0 | 0.7 |

| M | 34.7 ± 33.2 | ||

| SF-36 Social Function | F | 35.5 ± 39.1 | 0.07 |

| M | 29.7 ± 38.9 | ||

| SF-36 Physical Component | F | 13.7 ± 14.0 | 0.84 |

| M | 13.9 ± 14.7 | ||

| WOMAC Function | F | 36.39 ± 18.9 | 0.004 |

| M | 31.96 ± 19.6 | ||

| WOMAC Pain | F | 10.59 ± 5.47 | 0.003 |

| M | 9.28 ± 5.74 | ||

| WOMAC Stiffness | F | 3.23 ± 2.71 | 0.001 |

| M | 2.49 ± 2.72 | ||

| Harris hip score | F | 44.9 ± 32.1 | 0.38 |

| M | 42.5 ± 35.8 | ||

| Postel D’Aubigne hip score | F | 7.05 ± 7.61 | 0.13 |

| M | 6.10 ± 7.96 |

QWB = Quality of Well-being; F = female; M = male.

Table 4.

Preoperative ROM for gender

| Outcome measures | Gender | Mean ± SD | p | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| Hip abduction extension | F | 24.9 ± 13.1 | 0.28 | 23.5 | 26.2 |

| M | 25.6 ± 14.1 | 24.1 | 27.3 | ||

| Hip flexion | F | 76.8 ± 28.6 | 0.46 | 74 | 79.7 |

| M | 79.2 ± 26.9 | 76.1 | 82.4 | ||

| Hip adduction extension | F | 16.5 ± 10.7 | 0.05 | 15.4 | 17.6 |

| M | 18.2 ± 11.9 | 16.8 | 19.6 | ||

| Hip internal rotation | F | 7.74 ± 10.3 | 0.73 | 6.7 | 8.7 |

| M | 8.03 ± 10.9 | 6.7 | 9.3 | ||

| Hip external rotation | F | 20.4 ± 16.3 | 0.15 | 18.7 | 22.1 |

| M | 22.2 ± 16.5 | 20.3 | 24.2 | ||

F = female; M = male.

Table 5.

Postoperative ROM for gender

| Outcome measures | Gender | Mean ± SD | p | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| Hip abduction extension | F | 41.8 ± 8.67 | 0.04 | 40.9 | 42.7 |

| M | 40.4 ± 8.13 | 39.4 | 41.4 | ||

| Hip flexion | F | 99.1 ± 15.2 | 0.14 | 97.5 | 100.6 |

| M | 97.2 ± 16.2 | 95.2 | 99.1 | ||

| Hip adduction extension | F | 30.1 ± 9.86 | 0.14 | 29.1 | 31.1 |

| M | 28.9 ± 10.1 | 27.7 | 30.1 | ||

| Hip internal rotation | F | 23.2 ± 11.5 | < 0.0001 | 22.1 | 24.4 |

| M | 19.8 ± 11.5 | 18.4 | 21.2 | ||

| Hip external rotation | F | 41.3 ± 11.3 | 0.06 | 40.1 | 42.5 |

| M | 39.5 ± 12.6 | 38.1 | 41.1 | ||

F = female; M = male.

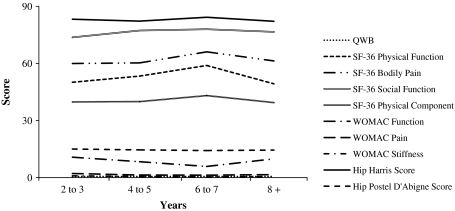

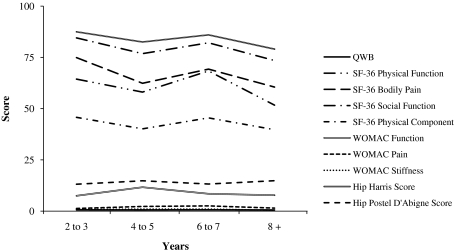

By 6 to 7 years, both females (Fig. 1) and males (Fig. 2) began to trend toward worse perceived functional recovery for a majority of outcome measures through 8 years thereafter. Beginning at the 2- to 3-year followup, males presented with a trend toward worse scores through the 4- to 5-year followup followed by a return of improved perceived outcome by 6 to 7 years (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

The distribution of outcome measures through time for females is shown. By 6 to 7 years, females began to trend toward worse perceived functional recovery for a majority of outcome measures through 8 years thereafter. QWB = Quality of Well-being.

Fig. 2.

The distribution of outcome measures through time for females is shown. By 6 to 7 years, males began to trend toward worse perceived functional recovery for a majority of outcome measures through 8 years thereafter. QWB = Quality of Well-being.

Females and males had similar (p = 0.15) hospital length of stay (4.6 days ± 1.9 SD) (5.0 days ± 2.2 SD. There was no relationship (phi = 0.29) between type of complication and whether being male or female (Table 6).

Table 6.

Complications

| Complication | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|

| Medical | ||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 5 | 7 |

| Pulmonary embolus | 1 | 1 |

| Clostridium difficile diarrhea | 1 | 1 |

| Orthopaedic | ||

| Superficial/deep infection | 5 | 11 |

| Fracture femur | 5 | 4 |

| Dislocation | 2 | 2 |

| Implant failure | 1 | – |

| Patellar fracture | – | 1 |

Discussion

While THA improves function with high long-term survivorship, differences in function and disability between men and women before and after arthroplasty are not well understood. Our initial goal of this study was to compare perceived measures of well-being, function, and pain between females and males before and after THA. We therefore (1) compared perceived measures of well-being, function, and pain between females and males before THA and on average 5 years; (2) compared the improvement in perceived measures of well-being, function, pain, and ROM between females and males at followup; and (3) determined the time course of perceived functional recovery in females and males by presenting the results graphically over time.

Limitations of this study include the following: First, we did not include other potential confounding factors such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or patient expectations. Such confounding factors could explain some of the differences independent of gender and we cannot ensure any differences we observed were not due to uncontrolled variables. However, we did have a fairly large number of participants and did account for age and body mass index covariates in our statistical model. Second, the differences between genders before surgery measured in our study and those previously reported could be differences in self-perception by gender. Women could perceive their pain and function as more limiting than what they really are or, alternatively, males could overestimate their pain relief and functional performance. Benyamini et al. found women’s perception of their self-assessed health ratings mostly responds to a wide range of nonhealth-related (dimensions that are not related to mortality) as well as health-related factors, whereas men’s tend to be more closely tied to their physical status when performing this assessment [4]. Under the same premise, Kennedy et al. reported low to moderate correlations between self-report and physical performance measures in patients awaiting THA and TKA [18]. These studies suggest objective evaluations should be included in future studies. Thus, we recommend that further investigations be completed that include both perceived and functional performance measures when evaluating differences between women and men after joint arthroplasty.

Two studies suggest most THAs are currently performed in women [2, 26]. In our cohort, 59% of THAs were performed on women. Our data showed women had worse preoperative scores for all dependent measures. Postoperatively, we found no difference in all outcome measures between women and men. Both genders had improvements in all outcome measures after surgery. Yet our data suggest women experienced larger postoperative improvements in the WOMAC physical function, pain, stiffness, and total scores. Similarly, Kostamo et al. reported greater change score for women than for men in the WOMAC pain score [20]. One possible explanation of our results is that women presented with worse scores preoperatively because they delayed or “waited too long” to have their surgery [21]. Previously, we reported on patients who presented for surgery with severe physical function impairment (as measured by the WOMAC function score) [21]. This cohort had poorer outcomes relative to patients who had more favorable preoperative physical function scores. These differences persisted even 3 years after joint arthroplasty. This could partially explain why women tended to have worse scores postoperatively (although not significant) and did not reach postoperative levels reported by men. Kennedy et al. [19] reported patients with better preoperative scores predicted quicker improvement in their walking distance postoperatively. In their model, although women began with worse function, their rate of recovery was similar to that of men [19]. Although their data are in agreement with ours in the presurgical evaluation, postoperatively, they did not report a difference in improvement rate between women and men. They only studied their subjects for a short time (4 months). Our data exclude that period of time and focuses on the longer followup (average 5 years 6 months).

We found women reported lower preoperative scores, and despite their greater improvements in certain measures of perceived function, women continue to have lower postoperative scores when compared with men 5 years 6 months after surgery. These findings suggest perhaps women tolerate pain and disability better than males and are able to perform their activities of daily living with a higher level of pain when compared with males. This difference is relatively small and its clinical importance remains questionable.

Specific anatomic differences between men and women have been described around the hip. On the femoral side, specific differences are reported in femoral offset and femoral head height [27, 30]. However, we found no difference in ROM between men and women at the preoperative assessment. At followup women had greater mean hip abduction and internal rotation compared with men (Table 7).

Table 7.

ROM literature review

| Outcome measures | Hip flexion | Hip abduction extension | Hip internal rotation | Hip external rotation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kendall and Wadsworth [17] | 125 | 45 | 45 | 45 | |

| Daniels and Worthingham [10] | 115–125 | 45 | 45 | 45 | |

| Hoppenfeld [13] | 120 | 45–50 | 35 | 45 | |

| Mohr [25] | 120 | 45 | 45 | 45 | |

| Cailliet [6] | 120 | 45 | 45 | 45 | |

| Cole [8] | 120 | – | 45 | 40 | |

| Lavernia et al. [currrent study] | F | 99.1 | 41.8 | 23.2 | 41.3 |

| M | 97.2 | 40.4 | 19.8 | 39.5 |

F = female; M = male.

Examining the time course of recovery, it appears that perceived well-being, pain, and physical function declines through 4 to 5 years after surgery in men; this decline was not observed in women.

Our data showed no difference in length of stay between females and males and a similar number and type of complications between genders. In agreement with our study, numerous reports have found no difference in complications between females and males after total joint arthroplasty [16, 24, 29].

Women do very well after primary THA in the areas of perceived clinical outcome and perceived pain relief. However, globally women presented to surgery with lower preoperative scores when compared with men. Women do have equal or better hip ROM 5 years 6 months after surgery and present with better perceived recovery than men through 7 years after THA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mercy Hospital, the Mercy Foundation, and the Arthritis Surgery Research Foundation Inc for the financial support received to perform this investigation.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at the Orthopaedic Institute at Mercy Hospital, Miami, FL, USA.

References

- 1.Arocho R, McMillan CA, Sutton-Wallace P. Construct validation of the USA-Spanish version of the SF-36 health survey in a Cuban-American population with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:121–126. doi: 10.1023/A:1008801308886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron JA, Barrett J, Katz JN, Liang MH. Total hip arthroplasty: use and select complications in the US Medicare population. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:70–72. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benyamini Y, Leventhal EA, Leventhal H. Gender differences in processing information for making self-assessments of health. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:354–364. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200005000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bozic KJ, Saleh KJ, Rosenberg AG, Rubash HE. Economic evaluation in total hip arthroplasty: analysis and review of the literature. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:180–189. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00456-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cailliet R. Soft Tissue Pain and Disability. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Co; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole T. Goniometry: The Measurement of Joint Motion. 2. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Ambrosia RD. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Orthopedics. 2005;28(Suppl):s201–s205. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20050202-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniels L, Worthingham C. Muscle Testing: Techniques of Manual Examination. 3. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 11.d’Aubigne RM, Postel M. The classic: functional results of hip arthroplasty with acrylic prosthesis. 1954. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:7–27. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0572-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoppenfeld S. Physical Examination of the Spine and Extremities. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan RM, Alcaraz JE, Anderson JP, Weisman M. Quality-adjusted life years lost to arthritis: effects of gender, race, and social class. Arthritis Care Res. 1996;9:473–482. doi: 10.1002/art.1790090609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan RM, Bush JW. Health-related quality of life measurement for evaluation research and policy analysis. Health Psychol. 1982:61–80.

- 16.Katz JN, Wright EA, Guadagnoli E, Liang MH, Karlson EW, Cleary PD. Differences between men and women undergoing major orthopedic surgery for degenerative arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:687–694. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kendall HO KF, Wadsworth GE. Muscles: Testing and Function. 2. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy D, Stratford PW, Pagura SM, Walsh M, Woodhouse LJ. Comparison of gender and group differences in self-report and physical performance measures in total hip and knee arthroplasty candidates. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:70–77. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.29324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy DM, Hanna SE, Stratford PW, Wessel J, Gollish JD. Preoperative function and gender predict pattern of functional recovery after hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kostamo T, Bourne RB, Whittaker JP, McCalden RW, MacDonald SJ. No difference in gender-specific hip replacement outcomes. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:135–140. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0466-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavernia C, D’Apuzzo M, Rossi MD, Lee D. Is postoperative function after hip or knee arthroplasty influenced by preoperative functional levels? J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:1033–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lieberman JR, Dorey F, Shekelle P, Schumacher L, Kilgus DJ, Thomas BJ, Finerman GA. Outcome after total hip arthroplasty. Comparison of a traditional disease-specific and a quality-of-life measurement of outcome. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:639–645. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(97)90136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marchetti P, Binazzi R, Vaccari V, Girolami M, Morici F, Impallomeni C, Commessatti M, Silvello L. Long-term results with cementless Fitek (or Fitmore) cups. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:730–737. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mesa-Ramos F, Mesa-Ramos M, Maquieira-Canosa C, Carpintero P. Predictors for blood transfusion following total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomised study. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohr T. Musculoeskeletal Analysis:TtheHip. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Co; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilsdotter AK, Lohmander LS. Age and waiting time as predictors of outcome after total hip replacement for osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:1261–1267. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.11.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noble PC, Box GG, Kamaric E, Fink MJ, Alexander JW, Tullos HS. The effect of aging on the shape of the proximal femur. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;316:31–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Connor MI. Osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: sex and gender differences. Orthop Clin North Am. 2006;37:559–568. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spirt AA, Assal M, Hansen ST., Jr Complications and failure after total ankle arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1172–1178. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200406000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugano N, Noble PC, Kamaric E. Predicting the position of the femoral head center. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:102–107. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(99)90210-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tosi LL, Boyan BD, Boskey AL. Does sex matter in musculoskeletal health? The influence of sex and gender on musculoskeletal health. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1631–1647. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]