Abstract

Proteolytic activity is important in the lifecycles of parasites and their interactions with hosts. Cysteine proteases have been best studied in Giardia, but other protease classes have been implicated in growth and/or differentiation. In this study, we employed bioinformatics to reveal the complete set of putative proteases in the Giardia genome. We identified 73 peptidase homologues distributed over 5 catalytic classes in the genome. Serial analysis of gene expression of the G. lamblia lifecycle found thirteen protease genes with significant transcriptional variation over the lifecycle, with only one serine protease transcript upregulated late in encystation. The translated gene sequence of this encystation-specific transcript was most similar to eukaryotic subtilisin-like proprotein convertases (SPC), although the typical catalytic triad was not identified. Epitope-tagged gSPC protein expressed in Giardia under its own promoter was upregulated during encystation with highest expression in cysts and it localized to encystation-specific secretory vesicles (ESV). Total gSPC from encysting cells produced proteolysis in gelatin gels that co-migrated with the epitope-tagged protease in immunoblots. Immuno-purified gSPC also had gelatinase activity. To test whether endogenous gSPC activity is involved in differentiation, trophozoites and cysts were exposed to the specific serine proteinase inhibitor 4-(2-Aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride (AEBSF). After 21 h encystation, a significant decrease in ESV was observed with 1 mM AEBSF and by 42 h the number of cysts was significantly reduced, but trophozoite growth was not inhibited. Concurrently, levels of cyst wall proteins 1 and 2, and AU1-tagged gSPC protein itself were decreased. Excystation of G. muris cysts was also significantly reduced in the presence of AEBSF. These results support the idea that serine protease activity is essential for Giardia encystation and excystation.

Keywords: Giardia lamblia, protease, subtilisin-like proprotein convertase, encystation, excystation, serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE)

1. Introduction

Giardia lamblia is a major cause of waterborne diarrheal disease worldwide [1, 2]. Giardia cycles between two developmental and morphological forms, the trophozoite and the cyst. Trophozoites colonize the upper small intestine by attaching to epithelial cells where they can cause disease. Infection with Giardia does not typically cause inflammation and parasites do not invade the host mucosa or damage intestinal tissues. When trophozoites descend through the small intestine, they generate a rigid extracellular matrix, or cyst wall (CW), that protects them from the external environment (Rev. [3]). The CW also protects the parasites from gastric acid as they pass through the stomach of a new host before reaching the small intestine where they excyst. Since cysts are the infective stage for mammalian hosts, these differentiations are key to Giardia’s survival and its success as a pathogen.

Formation of the resistant extracellular CW begins with intestinal signals that induce the transcriptional upregulation and expression of cyst wall proteins (CWP) [4–7] and the enzymes needed for their processing or post-transcriptional modifications [8–12]. Four structural CWPs have been identified, CWP1, 2, and 3, and high cysteine non-variant cyst protein (HCNCp). All CWPs are transported via encystation-specific secretory vesicles (ESV) and are released at the site of CW assembly. Each of these proteins contains cysteine residues that form extensive intermolecular disulfide bonds during maturation and transport. Additionally, CWP2 and HCNCp in the mature CW are proteolytically processed. It is not known which peptidase(s) cleave HCNCp, but cysteine proteinase 2 (CP2) [9] within the ESV and perhaps lysosomal encystation-specific cysteine protease (ESCP) [8] can cleave CWP-2 into its mature form. The physiological signal(s) that leads to autocatalytic activation of CP2 is not known. Export of mature CWP may be calcium dependent based on evidence provided by Touz and colleagues [13] who were able to show that knockdown of granule-specific calcium-binding protein (gGSP) prevents ESV from releasing CWP. Like CWP2 and HCNCp, gGSP is proteolytically processed during encystation; however, the pathways responsible have not been identified. The mature CW also contains fibrils of poly N-acetylgalactosamine or CW glycopolymer (CWG) [10, 14, 15] that contribute to the strength of the cyst wall, although its architecture is not well-understood.

Encystation must be tightly regulated to ensure the synthesis, trafficking, and processing of encystation-specific gene products, resulting in their deposition to the nascent CW matrix at the proper time and place [3]. Proteases play an essential role in these processes and may be drug targets to interfere with transmission or replication of parasites [16]. To date, CP2 [9], encystation-specific cysteine protease (ESCP) [8], and the bestatin-binding membrane-associated dipeptidyl [17] peptidases are the best- characterized proteases in Giardia. Unlike CP2 and ESCP, inhibition with the protease inhibitor bestatin causes a complete block of transcriptional activation of CWP1 and 2 during encystation. Activity of other protease types have been detected in the life cycle of Giardia (e.g. [18–23]), but the enzymes have yet to be identified. Notably, cysteine protease activity is also reported to be critical during excystation of Giardia [24].

Cysteine protease activity is the most abundant proteolytic activity detected in Giardia as in many other protozoan parasites [25–28]. Through transcriptome analyses of the Giardia life cycle [29] we identified a putative prohormone peptidase, gene ID GL50803_2897, with increased expression late in encystation. This protein was recently identified as one of the most abundant wheat germ agglutinin (WGA)-binding glycoproteins in encysting Giardia [30]. Sequence comparisons revealed that it is most similar to subtilisin-like proprotein convertases (SPC) of the serine protease family. SPCs are calcium dependent serine endopeptidases that cleave diverse pro-peptides into molecules that are frequently biologically active [31–33]. Cleavage of substrates typically occurs after a pair or series of basic residues. SPCs have conserved structural and functional regions, and the catalytic domain has positionally conserved amino acid residues. These regions are [31, 34, 35]: the N-terminal signal peptide for transport through the secretory system, the partially conserved pro-domain that assists in intramolecular chaperone folding within the ER and is usually autocatalytically cleaved [36, 37], the conserved subtilisin-like catalytic segment with three positional active site residues, and the highly conserved P-domain that stabilizes the catalytic domain and may regulate pH and calcium dependence [34, 38]. A variable carboxyl-terminal extension follows the P-domain of SPCs. Several subtilisin type serine proteases have been detected and characterized in protozoan parasites (e. g., [39–44]), however none of those can be classified as a SPC.

SPCs are critical in activating precursor proteins into biologically active forms through regulated proteolysis and are considered novel targets for drug design [32, 34]. We found a single SPC-like gene in the Giardia degradome, (GL50803_ 2897; gSPC), and we evaluated its role in the life cycle. We demonstrate that AU1-tagged gSPC protein is upregulated in encystation and follows traffic of CWPs to the ESV, but not to the CW. Exposure to the serine protease inhibitor AEBSF resulted in a dramatic block of encystation and excystation, although growth was not affected. The natural substrates for gSPC have not yet been defined. gSPC is catalytically active even though the classic catalytic triad is not readily apparent in this enzyme. Although gSPC was classified as a non-peptidase homologue in MEROPS we detected proteolytic activity. Because of the extensive divergence of many giardial sequences[45], we included other protease homologs considered as “non-peptidase” in our examination of the Giardia degradome.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Giardial cultivation and encystation

Giardia lamblia isolate WB clone C6 (ATCC 50803; [46]) was grown in modified TYI-S33 medium and encysted as described [47] with the modification that bovine bile (Ox gall, unfractionated; Sigma B3883) was substituted for porcine bile at a final concentration of 1.3 mg/ml.

2.2. Detection of G. lamblia peptidase homologs

To achieve maximum sensitivity for the detection of Giardia peptidases, the non-redundant library of peptidase units and inhibitor unit proteins (pepunit.lib; 120,595 annotated sequences) from the MEROPS Release 8.4 (April 3, 2009) [48] was used to query the GiardiaDB (Release 1.1, May 12, 2008) database (http://www.giardiadb.org/giardiadb/). The searches were restricted to only the peptidase and inhibitor units library to decrease the possibility of matches to false positives or non-peptidase domains. To assign current GiardiaDB sequence identifier to the existing MEROPS identifiers and to discover any new peptidases, BLASTP (cutoff E-value ≤ e-6) was used on locally installed WU-Blast2 [49] software. To confirm the presence of relevant peptidase functional domains, any peptidase homolog detected using BLASTP was tested locally using the hmmscan algorithm in HMMER3 [50] against the Pfam 23.0 (July 2008, 10,340 families) pro le HMM database [51]. Any putative Giardia peptidase not found in the current MEROPS release was assigned the Clan, Family or MEROPS identifiers using the highest hit from the MEROPS BLAST search engine. All results were cataloged in an Excel spreadsheet. MEROPS annotation is as defined previously [52, 53]. For example, a non-peptidase homologue is defined as similar in tertiary structure to a peptidase family gene product, but may lack one or more critical catalytic residues thought to be essential for peptide hydrolysis. A protein that is labeled as “unassigned peptidases” is structurally catalytic, but its species classification within a specific peptidase family could not be determined at the time of our analysis.

To obtain the nucleotide sequence of the GS gSPC homolog we first used BLASTn to search the Assemblage B GS genome, using the WB gSPC sequence as the query. The BLASTn search was done through the GiardiaDB website (http://giardiadb.org/giardiadb). The top hit was from contig ACGJ01002589, which contained the gSPC sequence from the start codon to position 2,217 of the nucleotide sequence (positions 1 to 2,217 of the contig) on the reverse strand. The second hit from contig ACGJ01002292 contained position 1,812 to the stop codon of the GS gSPC sequence (positions 35,222 to 35,733 of the contig). The overlapping sequence matched 100 percent. The resulting full length GS gSPC gene was 2,322 nucleotides, encoding a 773 amino acid protein. BLASTp was used to obtain the Assemblage E P15 gSPC homolog from the GiardiaDB website. The protein sequences of the gSPC homologs from WB, GS and P15 were aligned using CLUSTALW and the BLOSUM weight matrix.

2.3. Gene identification: mRNA expression patterns

SAGE libraries were constructed as described previously [54]. The unique tag sequences were mapped to all available Giardia genome assembly contigs (http://www.giardiadb.org/giardiadb/) to determine the identity of expressed genes. As mRNA transcripts can generate more than one SAGE tag due to incomplete Nla III digestion during SAGE library construction, abundance values for transcripts were the sum of all SAGE tags along the entire transcript. Transcripts were modeled [29] as the ORF plus a 15 bp 3 UTR, with correction using the 20,238 EST sequences released with the publication of the Giardia genome project. We used Stekel et al. s R-statistic [55] to in effect score transcripts on differential expression over the life cycle (more variable tags have higher R-values). We further used Stekel et al. s application of the Theory of Large Deviations [55] to identify tags with high log-likelihood values representing true variation not false positive results. Tags with R≥8 were considered significant. Initial examination of the SAGE results for genes upregulated during encystation led to discovery of GL50803_2897 (deposited to NCBI under accession number AY769361).

2.4. Protein characterization of gSPC

The amino acid sequence similarity of gSPC was queried using NCBI BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and conserved domains were identified using InterPro Scan (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/InterProScan/). The signal peptide prediction was evaluated using SignalP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/), and transmembrane helix prediction was determined using TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/).

2.5. Selectable transformation and epitope tagging of gSPC

The promoter and coding sequences for gSPC (GL50803_2897; genomic nucleotide position -197 to 2,325) were amplified from 200 ng of genomic DNA using the forward primer “gSPC-for” (5′-gagaattcgactttaccatcagagcc-3′; Proligo, Boulder, CO) and the reverse primer “gSPC-rev” (5′-atgggccccttgagcactagagca-3′; Proligo), or the forward primer “gSPC-HA-for” (5′-gggcccgactttaccatcagagccatc-3′; Operon, Huntsville, AL) and the reverse primer “gSPC-HA-rev” (5′-gatatccttgagcactagagcagctg-3′, Operon, Huntsville, AL) for HA-epitope tagging with Platinum® Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at a final concentration of 2 mM MgSO4 by standard methods. Conditions for PCR were an initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, 30 cycles of: 95 °C 30 sec, 53 °C 1 min, 72 °C 2 min 30 sec; and a final extension for 10 min at 72 °C (MJ Research, Waltham, MA). Approx. 1 μg each of the ~2.5 kb PCR products and AU1-epitope or HA-epitope tagging Giardia vectors [56, 57] were double digested for 1 h 37 °C Apa1 and EcoRI for AU1-epitope tagging or Apa1 and EcoRV for HA-epitope tagging and gel purified using QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The vectors were de-phosphorylated using shrimp alkaline phosphatase (Promega; Madison, WI) by standard methods and purified using QIAquick (Qiagen). The digested vectors and PCR fragments were ligated (T4 DNA ligase; Roche, Nutley, NJ) overnight at 4 °C, transformed into JM109 competent cells (Promega), and plasmids screened by size for automated sequencing of clones containing full-length gSPC. WB clone C6 trophozoites were electroporated with 50 μg of plasmid containing gSPC-AU1 or gSPC-HA and were selected and maintained by puromycin resistance [58].

2.6. Immunoblot analyses of gSPC

Trophozoite, encysting cells, and cyst antigens from Giardia stably expressing the AU1-tagged gSPC gene or non-transfected control cells were processed for Western analysis [59]. Protein lysates were also size fractionated on 6% gels and transferred to PVDF to determine timing of protease processing. Blotted proteins were blocked overnight in PBST (PBS + 0.05% Tween 20) containing 5% milk, probed in mouse anti-AU1 (1/1,000 in PBST/0.1% milk; Covance; Berkeley, CA) or anti-alpha tubulin (1/1,500 in PBST/0.3% milk; loading control; Sigma, clone 1A) antibodies for 1.5 h, washed 3X over 30 min in PBST, incubated in Zymax goat anti-mouse (GAM)-HRP (1/8,000; Zymed Laboratories/Invitrogen) for 1 h, washed 3X in PBST over 30 min, and developed in ECL Plus (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

2.7. Immunolocalization of gSPC

Trophozoites and encysting parasites stably expressing AU1-tagged gSPC or non-transfected control cells were prepared for immunofluorescence assay and imaged as described in Davids et al., 2006 [7]. For excystation, the protocol of Boucher and Gillin (1990; [60]) was utilized. Excyzoites were placed on SuperStickTM slides (Waterborne, Inc., New Orleans, LA) for 5 min at 37°C before fixation and processing for gSPC localization as above.

2.8. Zymography and inhibition of gSPC activity

Cell lysates from gSPC AU1-tagged trophozoites at 42h and cysts were made in 0.25 M sucrose containing 10 μM of the cysteine proteinase inhibitor E-64 [23]. Five μg of each crude protein lysate was separated on a 10 % gelatin gel (Zymogram; Invitrogen), renatured 30 min in 2.7% Triton X-100, developed overnight at 37°C in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris base, 40 mM HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, and 0.02% Brij 35, pH 7.6, and stained with Coomassie Blue. After development of the zymogram, proteins from the same gel were electrotransferred to nitrocellulose, probed with anti-AU1 and goat anti-mouse-HRP antibodies as above, and developed with the ECL substrate (Amersham).

A variety of serine protease inhibitors were used to inhibit the activity of endogenous gSPC. Five μg of 42 h encysting cell lysate was pre-incubated with 4-(2-Aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride (AEBSF; Sigma; ≤ 100 mM), phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF; Sigma; ≤ 5 mM), Bestatin (Sigma; ≤ 5 mM), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Sigma; ≤ 1 mM) or Benzamidine (Sigma; ≤ 100 mM) for 1 min at 37°C followed by 30 min RT. Treated lysates were separated on a gelatin gel and activity evaluated as described above.

2.9. Purification and assay of gSPC

Log phase WB (wild type; non-transfected) and gSPC-HA expressing cultures of G. lamblia (1.5L) were placed in encystation media for 21 hrs. The parasites were concentrated and washed twice in cold PBS and once in cold 25 mM Tris pH 7 and 100 mM NaCl. The pellets were diluted with lysis buffer (25 mM Tris pH 7, 100 mM NaCl, and 100 μM E-64; Roche) to a cell density of 1×108 cells/ml. The parasites were lysed by sonication and lysis was checked by light microscopy. The lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The cleared wild type and gSPC lysates were loaded twice onto separate 200 μL anti-HA agarose (Roche) gravity columns. The columns were washed with 10 ml of 25 mM Tris pH7, 1 M NaCl, and 100 μM E-64. The beads were then diluted in 1 column volume of elution buffer (lysis buffer with 1mg/ml HA-peptide; Abbiotec, San Diego, CA) and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min in 1.5 ml tubes. The mixtures were then centrifuged for 2 minutes at 2,000 rpm to collect the beads and the supernatant was transferred to new 1.5 ml tubes. This was repeated for a total of three elutions, which were subsequently combined and concentrated 10-fold with Amicon Ultra 10K centrifugal filter units (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Immuno-purified gSPC-HA was detected by Western (HRP labeled anti-HA 1:1500; Roche) and tested for activity by gelatin zymography as described above.

2.10. Effects of protease inhibitor AEBSF on giardial growth. encystation, and excystation

We determined whether endogenous gSPC is involved in G. lamblia growth. Log phase C6 trophozoites were inoculated into growth medium at a density of 1.5 X 104 cells/ml in 4.5 ml glass screw-cap vials in the absence (water control) or presence of AEBSF (1.0-3.0 mM final concentration). Following 48 h of culture, the number of parasites/ml was determined using a hemacytometer and viability was assessed by dye exclusion using trypan blue (Gibco Life Technologies/Invitrogen). Greater than 98.9% cell viability was maintained over the 42 h time period for all treatments.

The importance of gSPC in encystation was validated by encysting log phase trophozoites in the absence (water control) or presence of AEBSF (0.1-3 mM final concentration) as described above. At 21 h encystation, the numbers of ESV/parasite were counted microscopically in live cells using Nomarski differential interference contrast (DIC) optics. Following 42 h encystation, parasites were washed 3X in refrigerated double distilled water and the numbers of water-resistant cysts were enumerated using a hemacytometer.

Excystation in the presence of AEBSF was also tested. Because in vitro-derived G. lamblia cysts require trypsin to stimulate excystation and AEBSF inhibits trypsin activity [60], we used G. muris fecal cysts to test whether excystation is sensitive to AEBSF [61]. 2–8 X 105 cysts were pre-treated in water in the absence (control) or presence of 3 mM AEBSF for 30 min on ice. Excystation was induced in 0.1 M potassium phosphate (starting pH 7.0) containing 0.3 M sodium bicarbonate (−/+ 3 mM AEBSF) for 15 min at 37 °C. Cysts were washed 1X with 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (37 °C; −/+ 3 mM AEBSF) and resuspended in modified TYI-S33 medium (pre-warmed to 37 °C; −/+ 3 mM AEBSF). Following 60 min of incubation, excyzoites were counted in a hemacytometer.

All data generated by AEBSF inhibition assays were repeated at least three times and data were statistically analyzed by ANOVA (Prism GraphPad, version 4.0c). Means comparisons were made using Tukey-Kramer s multiple comparisons test. P values of ≤ 0.05 were considered significantly different.

2.11. Western and qPCR analyses of AEBSF-treated parasites

Protein extracts of non-transfected C6, AU1-tagged gSPC or CWP3 [4] Giardia were prepared after 21 and 42 h of encystation in the absence (water control) or presence of AEBSF (1–4 mM) as described above. During AEBSF treatment of encysting cells, the puromycin selection antibiotic was removed from epitope-tagged cell lines. Proteins were separated and transferred to PVDF and Western blots with antibodies against the epitope-tagged CWP3 and gSPC were processed as above. CWP1 and CWP2 were detected by the primary monoclonal antibodies anti-CWP1 (1/2,500; [6]) and -CWP2 (1/500; antibody 8C5; [62]).

To quantify possible changes in transcription induced by inhibition of endogenous gSPC, mRNA transcripts of the known CWP genes and gSPC were quantified by qPCR. C6 parasites were encysted as above in the absence or presence of 2 mM AEBSF. After 21 h encystation, total RNA was purified using the PureLinkTM Micro-to-Midi Total RNA Purification System (protocol: purifying RNA from animal and plant cells; Invitrogen). DNA was degraded on-column as described in the optional methods with RQ1 DNase1 (Promega). cDNA was prepared from 5 μg of total RNA and 50 μM oligo (dT)20 primer by standard methods of the SuperScriptTM III 1st-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). Control reactions were minus reverse transcriptase for each RNA sample. QPCR primers were designed using the Realtime PCR algorithm through the PerlPrimer program (http://perlprimer.sourceforge.net). Primers for target genes of interest were as follows: CWP1 (5′ GCTCTATCTCAACTGCAACC 3′, 5′ TGGCAAGGTTCCACAG 3′; NCBI accession XM_001704838, GL50803_5638), CWP2 (5′ CTCAGGACAGTGGTTAGG 3′, 5′ TAGCATTGCCAGTCACAG 3′; NCBI accession XM_001710190, GL50803_5435), CWP3 (5′ TTCTTACCTGCGAGTTCTG 3′, 5′ AGCGAATTATTGTCCAAGTG 3′; NCBI accession XM_001707589, GL50803_2421), HCNCp (5′ GATTCTTCCCTGCCTTTAGTG 3′, 5′ CTATACAAATGCGACAACCC 3′; NCBI accession DQ144994, GL50803_40376), gSPC (5′ CAGCCTATCTCAAGTACCTG 3′, 5′ CAACATCCACTAGAGCAACC 3′; NCBI accession AY769361, GL50803_2897), and Giardia GL50803_9148 (housekeeping gene; 5′ CGTCATCAACAGGTCCGA 3′, 5′ CCAGCTCTCCTTGAACAC 3′; NCBI accession XM_001708537) (Allele Biotechnology, San Diego, CA). GL50803_9148 (annotated as H-Shippo1) was used as the reference gene because it is the second most abundant constitutively expressed and annotated gene in the Giardia life-cycle transcriptome (R-value=2.03; [29]). Amplification reaction mixture included 40 ng template cDNA, 0.1 μM forward and reverse primers, and 1X SYBRR AdvantageR qPCR Premix (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Mountain View, CA). Reactions were done in triplicate on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied BioSystems), and cycle thresholds (CT) were set uniformly across all gene analyzed following manufacturer s recommendations. Gene expression was quantified using the 2-ΔΔCT method [63], normalizing CT values to the H-Shippo1 reference gene.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The Giardia degradome and its transcriptome

Protease activities from several catalytic families have been detected in Giardia species (e.g. [18–23]). Global protease identification in Giardia has been advanced by using protease inhibitors or sequence homology searches. Some Giardia proteases have important functions in encystation [8, 9, 17], excystation [24, 64], and mitosome protein processing [65]. To date, the most abundant family of protease activity documented in Giardia and other protozoa is the cysteine type [16, 26, 27]. In Giardia cysteine proteases are essential for encystation and excystation, while in other protozoa they also have important functions in tissue invasion, protein processing, general catabolism, and immune evasion (Reviewed in [25]). Therefore, many of these cysteine proteases can be considered virulence factors and some are being targeted for antiparasitic chemotherapy [16]. Because proteases have key functions in the biology of Giardia they may be appropriate targets to reduce colonization or transmission. We used bioinformatic and transcriptomic approaches to identify the complete set of protease homologs in Giardia s genome (defined as “degradome”) during its life cycle (transcriptome of the degradome).

Our genome analyses revealed that the Giardia WB/C6 degradome consists of 73 putative protease genes (Table S1). All proteasome alpha subunits, having no known catalytic activity in any organism to date [66], with predicted catalytic residues of a peptidase or genes just below our trusted threshold were placed into a separate table for reference (Table S2) and these have not been included in any of our degradomic analyses. We included all predicted peptidase and non-peptidase homologues found in our searches (Table S1). We retained the non-peptidase homologues of proteinases in our dataset because there is mounting evidence (including this study) that the products of some of these genes can hydrolyze peptide bonds [67, 68]. For example, three human ubiquitin-specific proteases with residue substitutions in their catalytic triad are able to cleave ubiquitin from protein substrates. Moreover, Giardia has many fully functional enzymatic and cellular pathways that do not contain all the requisite components of model higher eukaryotes [45, 65]. The most highly represented protease family in the Giardia degradome is the cysteine type (36 members; 49.3%) (Table S1). This is consistent with a previous analysis of peptidase gene classes in the Giardia genome which found the largest distribution of peptidase genes in the cysteine catalytic family (38.9%) [53, 69]. However, 37 additional genes not included in Page and DiCera s dataset [69] and 13 genes not included in the MEROPS database [53] were identified by our bioinformatic criteria combined with the inclusion of the non-peptidase homologues. The remaining proteases were classified as metallo (18 members; 24.7%), serine (10 members; 13.7%), threonine (7 members; 9.6%), aspartic (1 member; 1.35%) and unknown (1 member; 1.35%) catalytic types. Overall, 1.46% of the annotated Giardia genome is composed of putative active peptidases (1.06%) and their predicted inactive homologues (0.40%). This is within the range, from 1%–2% [48], of most genomes. For a unicellular organism, Giardia exhibits a diverse repertoire of proteases and the roles of some of these proteases have been documented (Table S1). Giardia has specifically adapted to survive in both reducing and anaerobic environments, while undergoing two very different transformations during its life cycle. It must continue replicating while catabolizing a variety of nutrients, and defending itself against host defense factors in the gut. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that a wide variety of proteases would be necessary to accomplish these crucial cellular functions.

A global comparison of the WB/C6 degradome with that of other available giardial genomes, P15 and GSM, revealed a generally high amino acid conservation for those genes that were analogous within the current assemblies (Table S3). Amino acid identity with corresponding protease homologs of WB/C6 ranged from 77.6% to 98.6% for the P15 (giardial assemblage E) genome compared with 47% to 97.1% for the GSM (giardial assemblage B) genome. Previous phylogenic analyses showed a closer sequence relatedness of assemblage E isololates to assemblage A, compared to assemblage B isolates [70, 71]. In addition a recent genome analysis also confirmed high sequence divergence in the GSM genome [72]. Our comparative data also suggest that WB/C6 proteases are more similar to P15 than to GSM homologs.

A possible way to regulate proteinase activity in Giardia may be by expressing the non-peptidase homologues found in 4 of the 5 classes of peptidases in our degradome (Table S1; grey colored boxes). While many of these homologues may be catalytically active, it is likely that some are inactive peptidases. The most abundant catalytic class with non-peptidase homologues in Giardia is the metallo family (7 members; 38.9%), several of which are annotated as nuclear ATP/GTP binding proteins. The other three catalytic families with non-peptidase homologues are serine (4 members; 40%), threonine (4 members; 57.1%), and cysteine (5 members; 13.9%). It has been speculated that the distribution of non-peptidase homologues may not be random and that they may have regulatory roles, such as sequestering natural/endogenous protease inhibitors via their inactive catalytic domains to prevent their interaction with other key proteases in the cell [68, 73]. Testing this hypothesis would be an interesting direction for future degradomic studies in Giardia.

Many giardial genes are transcriptionally regulated. Therefore, we profiled transcription expression of each protease in our degradome using SAGE throughout the life cycle [29]. Seven of the 73 protease ORFs did not have SAGE tag or data (Table S4). Lack of SAGE data may indicate mRNA expression of those ORFs was below the detection limits of SAGE. However, in one case (GL50803_1995) the gene does not have an NlaIII site needed to produce a SAGE tag. Moreover, GL50803_113303 SAGE tag expression likely represents the expression of three ORFs (together with GL50803_114165 and GL50803_119224) that share significant nucleic acid identity (R-value shown under GL50803_113303). The relationship among the 10 SAGE libraries was analyzed using hierarchical clustering software. Each gene was evaluated for significant variation in abundance in context of the entire life cycle and each ORF was assigned an R-value. Any gene having an R-value ≥ 8 was considered to exhibit significant variation in abundance somewhere within the life cycle. All other genes with R-values < 8 have lower degrees of variation over the life cycle or have statistical noise in their data which needs to be extended by other techniques (e.g. qPCR) to determine precise transcriptional profiles.

SAGE identified 13 protease ORFs having R-values ≥ 8 that were distributed over 4 protease classes, half of which were cysteine proteases (Table S5). R-values ≥ 8 are taken to show statistically significant changes in expression over the life cycle [29]. All seven significantly regulated cysteine proteases were glycosylated [30] and included CP2 that can process CWP2 [9]. The most striking data for the cysteine protease family is the high expression of transcripts for ORFs GL50803_29304 (R-value 123.32) and GL50803_113303 (R-value 137.84; see notes in Table S5) with highest abundance in cysts and S1 excystation, and moderate abundance throughout excystation. This extends pre-genomic data that reported the importance of cysteine protease activity in giardial excystation [24, 64]. GL50803_27059 (R-value 9.32) had a similar SAGE profile, but it is a putative proteasome β6 subunit in the threonine catalytic family. Three of the 4 metalloproteases having significant variation were ORFs GL50803_15832, GL50803_8407, GL50803_17327 (R-values, respectively, 9.61, 9.96, 10.71; Table S5). However, their expression was highest in trophozoites and decreased during encystation. These metalloproteases may be important for the digestion of host peptides for nutrition or other pathogenic roles (reviewed in [25, 74]) and may be novel targets for drug development. The only serine protease that had significant variation in the Giardia life cycle was GL50803_2897, and it was the only protease ORF that was upregulated during encystation (Table S5). GL50803_2897 also had the highest transcript abundance from 12–42 h encystation among the identified serine proteases (Table S4).

3.2. Characterization of ORF GL50803_2897or “gSPC”

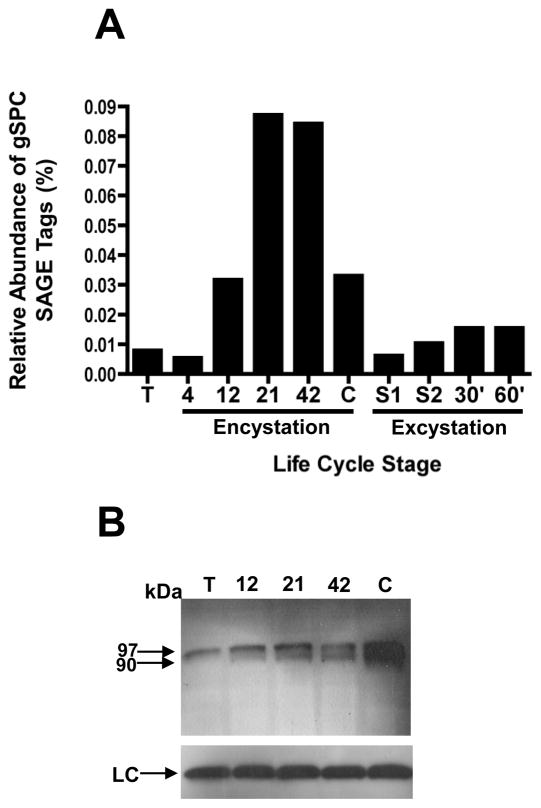

Transcriptome analysis (SAGE;[29]) revealed a number of genes whose expression was upregulated during encystation and whose roles in differentiation are not understood. As mentioned above, GL50803_2897 had a highly significant encystation-specific expression pattern that was highest at 21-42 h (Figure 1A; R-value=15.86). GL50803_2897 or “gSPC”(= Giardia Subtilisin-like Proprotein Convertase) encodes a putative proenzyme protease having a predicted mass of 83,317 kDa. Results of protein BLASTs against the non-redundant protein database with gSPC show sequence homology with SPCs. The highest sequence alignment was with an uncharacterized Trichomonas vaginalis putative SPC (e-value: 3e−27), followed by Acyrthosiphon pisum (pea aphid; e-value: 8e−21), Hydra magnipapillata (e-value: 9e−20), and Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (sea urchin; e-value: 1e−19) putative SPC genes. When compared to human genes, gSPC had the highest sequence homology to furin preproprotein (e-value: 5e−15). It is not unusual to have high sequence variability in the subtilisin-like serine proteases [75].

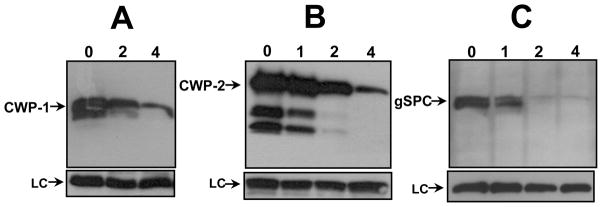

Figure 1.

gSPC mRNA transcripts and protein are upregulated during encystation. (A) An increase in the steady state abundance of gSPC transcripts was detected by SAGE beginning at “12” h through “42” h encystation compared to trophozoite (“T”) and “4” h encystation. A drop in gSPC transcript level was detected in cysts (“C”) through the excystation process (“S1, S2, 30 and 60 ). SAGE data is presented as percentage of all tags sampled at a given time point. (B) A 97 kDa AU1-tagged gSPC proprotein was detected in trophozoites (“T”), through encystation (“12”, “21”, and “42” h), and in water-resistant cysts (“C”) as detected in a Western. Beginning at 12 h encystation (“12”), the proprotein begins to be processed to the 90 kDa mature protease. Peak levels of protease, both proprotein and processed, were detected at the cyst (“C”) stage. The tubulin loading control is shown at the bottom of the figure (“LC”).

3.3. gSPC is up-regulated and proteolytically processed in encystation

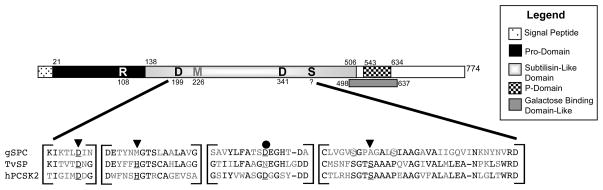

Since our transcriptome analyses indicated significant upregulation of gSPC transcripts in encystation, we epitope (AU1)-tagged GL50803_2897 and expressed it under its own promoter in Giardia. The expression levels of the AU1-tagged gSPC protein in stable transformants were similar to that of its mRNA levels, although water-resistant cysts had the highest amount of AU1-tagged gSPC protein (Fig. 1B). Full-length AU1-tagged gSPC was evident in trophozoites, encysting cells and cysts at an apparent Mr of 97 kDa. This size is larger than predicted, which may be in part due to GlcNAc2 and GlcNAc oligosaccharides that decorate the glycoprotein and alter its migration [30]. The 8 occupied Asn-linked glycosylation sites (or sequons) for endogenous gSPC can be viewed in supplemental file 1 of Ratner et al (2008; [30]). Cleavage of the proenzyme to Mr of ~90 kDa was apparent beginning at 12 h and increased during encystation. Active SPCs are classically cleaved from inactive pro-enzymes by an autocatalytic mechanism involving multiple steps in at least two compartments of the endoplasmic reticulum [36]. The first cleavage site for activation is usually a cluster of basic residues close to the boundary of the pro and catalytic domains. However, the only stretch of basic residues near this boundary is within the catalytic domain of gSPC (“K162KKIK167”; Fig. 2). Cleavage at this site would lead to an active product smaller than that we observe, suggesting that this is not the cleavage site. In some cases, activation of SPCs involves cleavage at a monobasic site in the pro domain, usually a single Arg residue [32]. There is only one Arg residue (Arg108; Fig. 2) in the pro domain of gSPC that might be a candidate. The active product would be approximately 87.4 kDa, depending on glycosylation, suggesting that Arg108 maybe the pro-peptide cleavage residue in gSPC. Comparisons of the GSM (GL50581_manual assembly; Fig. S1) and P15 (GLP15_3931) SPC homologs revealed that both genomes were conserved in this region and did not have alternative Arg residues, similar to gSPC.

Figure 2.

Diagram of structural organization of conserved domains of gSPC and sequence alignments of conserved regions around active site and oxyanion hole residues in the catalytic domain. Positioning of each domain is indicated with a different pattern (see legend box) and number indicates the amino acid start site of each domain and total protein length. Multiple amino acid sequence alignment of areas around the active site residues show that the position of Giardia s catalytic triad is divergent. Black text highlights at least two amino acid residues that are positionally identical among the three genes aligned. The position of the catalytic triad resides of the comparative sequences are indicated by the inverted triangles, the oxyanion hole residue is indicated by a solid black circle, and conserved residues are underlined. The two grey circles show the potential positions of the Ser reside that may be nucleophilic in catalysis for gSPC. Abbreviations: TvSP, Trichomonas vaginalis serine protease (XP_001304404); hPCSK2, human proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 2 (CAI20085).

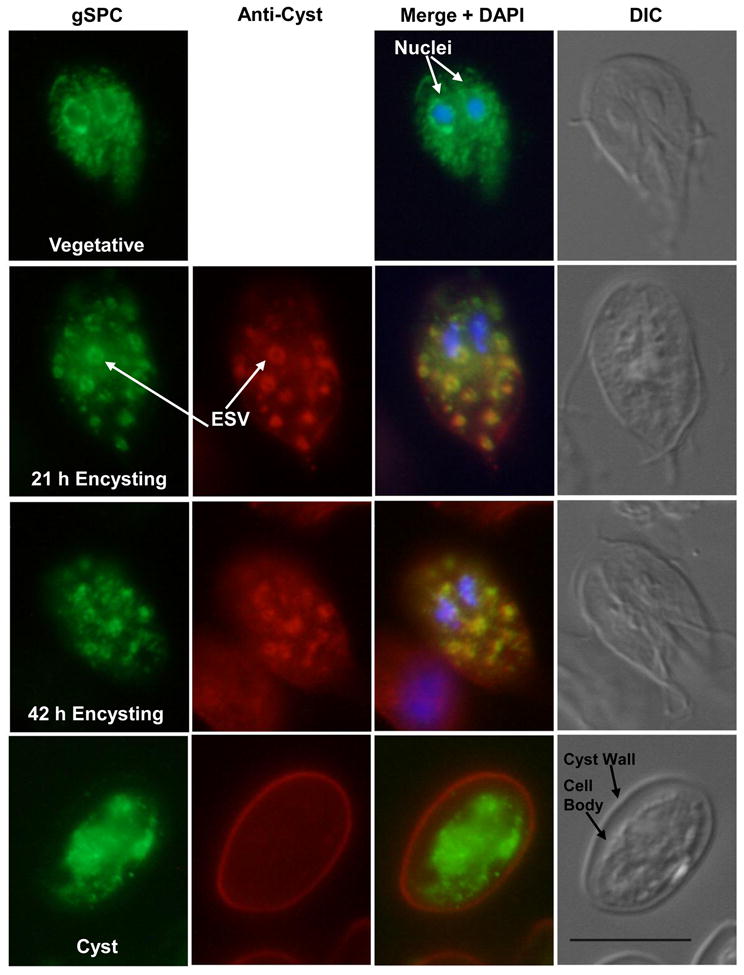

3.4. Localization of gSPC to the encystation pathway

In vegetative cells, we found AU1-tagged gSPC associated with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that extends from the nuclear envelope around both nuclei and throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 3, Vegetative). Co-staining with anti-PDI2 [76], an ER resident chaperone protein, confirmed this localization (not-shown). During encystation, gSPC co-localized with CWPs to the ESV (Fig. 3, 21 and 42 h Encysting panels). In contrast, in mature water-resistant cysts, the CWPs localized exclusively to the extracellular cyst wall (Fig. 3, Cyst panel) whereas gSPC was only detected in the cell body of the mature cyst and not in the cyst wall (Fig. 3, Cyst panel). Earlier, we evaluated the traffic of a variable surface protein (VSP)-like protein, HCNCp [7], that is also upregulated in encystation. In trophozoites it localized to the nuclei, while during encystation it co-localized with CWPs to the ESV, like AU1-tagged gSPC. In cysts, HCNCp largely localized to the cell body similar to AU1-tagged gSPC. However, some HCNCp was detected in the cyst wall, while gSPC was not. Thus, these proteins define two novel pathways for ESV-mediated transport that diverge from the better-studied CWP pathway. Perhaps the gSPC (and HCNCp) are stored in the cyst cell body for later use in excystation. We were unable to detect gSPC in excyzoites. This may indicate that AU1-tagged gSPC was degraded or released during the excystation process, or that the population of excyzoites we captured and viewed did not highly express the AU1- tagged gSPC, or that transformed cysts did not excyst well.

Figure 3.

Immunofluorescence assay showing traffic of AU1-tagged gSPC and cyst wall proteins during growth and differentiation. DIC images are shown to the right of each panel, AU1-tagged gSPC is shown in green (anti-AU1), anti-cyst proteins in red, and chromatin in blue (DAPI). In vegetative trophozoites, gSPC localized to the nuclear envelopes and ER (supported by co-staining with anti-PDI-2, not shown). During 21 and 42 h encystation, gSPC co-localized with cyst wall proteins in encystation-specific secretory vesicles (ESV) shown in yellow (“Merge”). In mature cysts, gSPC was only detected in the cell body and CWP in the cyst wall. Scale bar is 10 μM.

3.5. A potential galactose-binding domain in gSPC

Biosynthesis of the major cyst wall glycopolymer (CWG), poly b(1-3)-linked N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc), is specific to encystation [77, 78]. GalNAc is polymerized from UDP-GalNAc into insoluble cyst material by an unidentified “cyst wall synthase”. It is not known where the glycopolymer is assembled or how it is exported to the cyst wall or integrated with the protein components. Polymerization of CWG occurs in a particulate fraction, however, it is not known whether this corresponds to the ESV. One potential functional feature of gSPC is that it contains a predicted galactose-binding fold domain overlapping with the P-Domain in its carboxyl-terminal region (Fig. 2; IPR008979). This fold is found in at least 15 protein families whose roles primarily involve binding carbohydrate [79]. We speculate that endogenous gSPC may associate with CWG via this galactose-binding domain where it might assist in the transportation, polymerization, or processing of CW components. Interactions between gSPC, nascent CWG, and possibly other CW components could occur in the ESV prior to release from the cell because the protease does not localize to the cyst wall. Only one other ORF (GL50803_9948; Table S2) annotated as a hypothetical protein in the Giardia genome has a putative galactose-binding and subtilisin-like domains suggestive of a serine protease. However this was identified only by manual curation and was not detected by MEROPS (Table S2). This ~93.3 kDa protein has a transmembrane domain and is predicted to be catalytically inactive. It had increased mRNA expression at 21 h encystation in SAGE (Table S2), although its R-value was <8 and its translated glycoprotein was only found in Giardia cysts [30]. Pro-domains of subtilisins and SPCs can inhibit the proenzyme s activation by physically blocking the catalytic site [36, 80]. Additional studies are needed to evaluate whether the prodomains of gSPC or GL50803_9948 may serve a regulatory role in Giardia. Another function for this domain maybe to bind sugar residues in the intestine to assist newly excysted parasites in attachment. There is evidence that proteases secreted during excystation may aid in giardial adhesion [81].

3.6. gSPC proteolytic activity

gSPC has all the structural domains described for SPCs (Fig. 2). However, it is classified as a non-peptidase (catalytically inactive) homologue by MEROPS because one of the three positionally conserved active site residues in the catalytic domain is not evident [48]. This might change the dynamics of the charge relay system that the catalytic Ser-His-Asp triad typically uses for peptide bond hydrolysis. In gSPC, the Asp170 residue that is part of the catalytic triad and the Asp341 residue that forms the oxyanion hole during peptide hydrolysis are positionally conserved. However, the triad His residue is not apparent and appears to be replaced by a Met residue in gSPC (Fig. 2, lower alignment). The catalytic His residue is usually used to de-protonate the nucleophilic Ser during the acylation step of catalysis [35]. For gSPC, there are two possible nucleophilic Ser residues (Ser422, Ser429) in the vicinity where the conserved Ser residue is typically found in SPCs. Proteins lacking the catalytic triad are generally presumed to be proteolytically inactive, however, this has not always been proven [48, 67, 68]. At least three human cysteine proteases classified as non-peptidase homologues are active in hydrolyzing ubiquitin from substrate proteins. Since Giardia sequences are frequently highly divergent, gSPC may not conform to such predictions. Genomic analyses [45] show that giardial pathways are frequently reduced in complexity relative to other organisms, such as yeast. Therefore, we tested the proteolytic activity of endogenous gSPC in a zymogram under conditions favorable to SPCs.

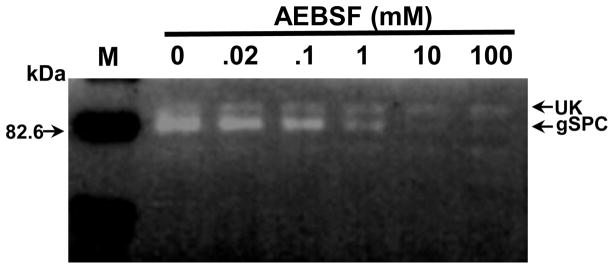

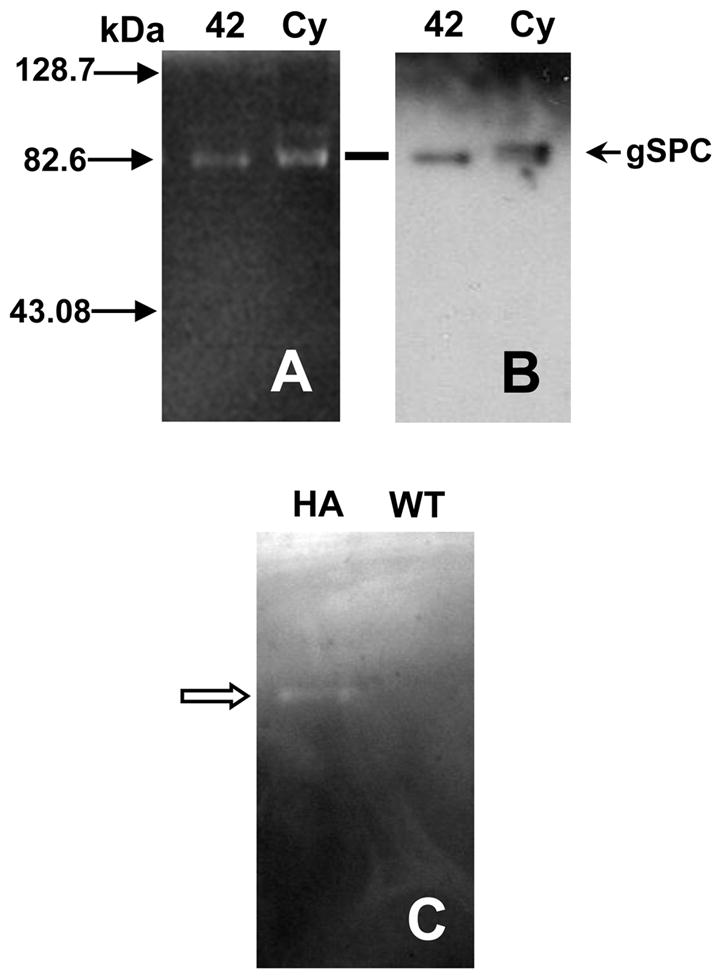

Analyses of crude extracts of encysting cells expressing AU1-tagged gSPC showed digestion of gelatin by only one major protease that migrated at the size of AU1-tagged gSPC (Fig. 4A) on a native 10% gelatin gel. A minor protease activity was several kDa larger (Fig. 4A, faint band above “gSPC”). The activities of these proteases were virtually non-detectable at acid pH (pH ≤ 5.2) or when Ca++ was limited (data not shown). Following in-gel zymogram development, the proteins were transferred to a membrane and probed with anti-AU1. We identified epitope-tagged gSPC in the major zone of proteolysis (Fig. 4B). Slightly more protein and activity were present in the cyst preparation. We were not able to determine whether the zone of proteolysis was due to the pro or processed gSPC, since they did not separate on a 10% gelatin gel. The ability of gSPC to cleave substrate was confirmed by immunopurification of HA-tagged gSPC (Fig. 4C). No gelatinase was detected following immunopurification of the non-transfected control (Fig. 4C). Our combined zymograms and immunoblots support catalytic activity of gSPC.

Figure 4.

Gelatinolytic activity of native, AU1-tagged, and immuno-purified HA-tagged gSPC. (A) Protease activity in lysates of encysting trophozoites “42” h encysting, and water-resistant cysts (“Cy”) was detected with gelatin as a substrate at pH 7.6 in presence of E-64 (cysteine protease inhibitor). (B) Following zymogram development, separated proteins in gels were electrotransferred to nitrocellulose and analyzed by Western for presence of the AU1 epitope tag. AU1-tagged gSPC was detected at the position of the lower zone of proteolytic activity (at line). Size markers are indicated by solid arrows on the left side of figure in kDa. (C) Anti-HA agarose immunopurified HA-tagged gSPC protein (“HA”) that showed gelatinolytic activity (see open arrowhead). This activity was absent in control wild type (“WT”; non-transfected) cell lysates purified by identical conditions.

3.7. gSPC is inhibited by serine protease inhibitors

As expected, endogenous gSPC was inhibited by several serine protease inhibitors. Our zymograms showed significant reduction of gelatin proteolysis by gSPC at 0.1 mM AEBSF and activity was virtually abolished at 10 mM (Fig. 5). We also saw partial inhibition of gSPC by PMSF (5 mM) and EDTA (1 mM), but no inhibition was apparent with inhibitors bestatin (metallo-aminopeptidase), benzamidine (trypsin-like), or E-64 (cysteine) (not shown). The minor protease (Fig. 5, labeled as “UK”) that is several kDa larger than gSPC was not sensitive to any of the protease inhibitors we tested, including AEBSF (Fig. 5) or 5 mM bestatin. Therefore, it is unlikely to be the membrane-associated dipeptidyl peptidase IV (GL50803_6148) described by Touz et al. (2002) [17] or another serine protease. It is also not a cysteine protease as E-64 is present in all of our preparations.

Figure 5.

Inhibition by AEBSF of gelatin degradation by total (endogenous and AU1-tagged) gSPC. For this assay, a constant amount of 42h encysting lysate (not live cells) was exposed to AEBSF. A dose dependent inhibition of gSPC was observed. The larger non-regulated unknown “UK” protease is unaffected by AEBSF and is not the precursor of gSPC. Endogenous and tagged-gSPC migrate at the same mass in 10% gelatin zymograms. A size marker (“M”) is indicated by an arrow on the left side of figure in kDa.

3.8. Giardial encystation and excystation are inhibited by AEBSF

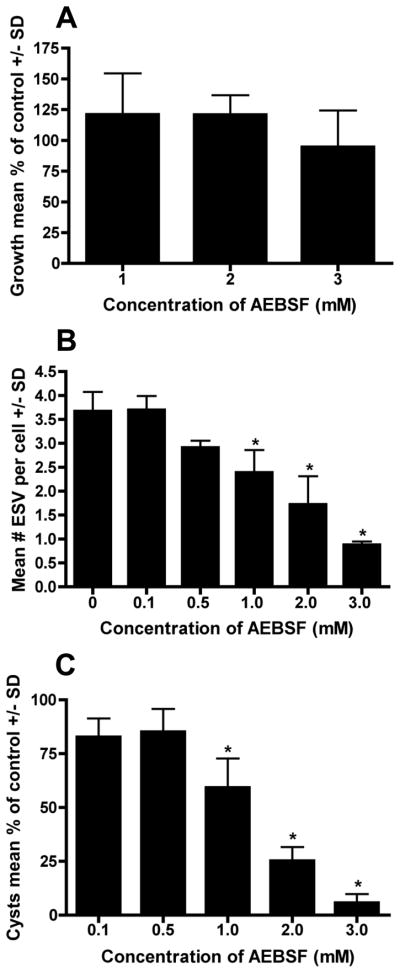

AEBSF is a sulfonyl fluoride broad-spectrum serine protease inhibitor that reacts irreversibly with the hydroxyl of the active site serine residue to form an inactive sulfonyl enzyme derivative [82]. The growth and/or host cell invasion of several protozoan parasites including Cryptosporidium parvum [41], Toxoplasma gondii [83], Sarcocystis neurona [43], and Plasmodium falciparum [44, 84] are sensitive to AEBSF in the 50 μM to 3 mM range. The filarial parasite Onchocerca volvulus has a true SPC, blisterase, which is inhibited by AEBSF and is speculated to be involved in adult cuticle maturation [85]. To test if serine proteinase activity is essential for growth or encystation, we exposed Giardia to up to 4 mM AEBSF. The viability of cells remained > 98.9% throughout all experiments. Exposure of trophozoites to increasing concentrations of AEBSF during 48 h did not significantly inhibit growth (P > 0.05 for all concentrations tested; Fig. 6A). This suggests that serine proteases sensitive to AEBSF are not crucial for cell division/growth and they would not be effective targets for anti-giardial chemotherapy.

Figure 6.

Effect of AEBSF on G. lamblia growth, ESV, and cyst formation. (A) Trophozoite growth was not significantly reduced over the 48 h culture period for all doses tested compared to the AEBSF-free control. Data are expressed as the mean percent control ± SD (N=4). (B) Exposure to ≥ 1 mM AEBSF resulted in a significant (*P<0.01 at 1 mM, P<0.001 for 2–3 mM) reduction in the number of ESV/trophozoite compared to the non-treated control at 21 h encystation. Data are expressed as the mean number of ESV/trophozoite ± SD (N=3). (C) When parasites were allowed to encyst for 42 h in ≥1 mM of AEBSF, a significant reduction (*P<0.001) in the formation of water-resistant cysts was detected. Data are expressed as the mean percentage of control ± SD (N=3).

In contrast, AEBSF was a potent inhibitor of Giardia encystation (Fig. 6B and C). Exposure of cells to 1-3 mM AEBSF in encystation resulted in 1.5 to 4.2-fold decrease in the mean number of ESV expressed per trophozoite (Fig. 6B) compared to the control. The same concentrations of AEBSF significantly reduced the ability of Giardia to differentiate into mature water-resistant cysts (Fig. 6C; P<0.001 for 1-3 mM). ESV package, process, and transport the known CWPs (CWP1-3, HCNCp) to form the final protective filamentous CW. Therefore, when insufficient numbers of ESV form and/or less proteins (CWP + other) are carried by ESV, it is likely that there will not be adequate amounts of CWP to form the cyst wall. This is similar to the effects of the transglutaminase inhibitor cystamine [59] and of other protease inhibitors [8, 17]. Inhibiting the early events of encystation amplifies the downstream defects in differentiation. This is reflected in the ~94% decreased cyst output for cells treated with 3 mM AEBSF (Fig. 6C). To date, SPC involvement in parasite encystation has not been reported, likely because SPCs are rare in protozoan parasite genomes [69]. However, a non-SPC protease in the same superfamily of subtilisin-like serine proteases [75] is essential for Acanthamoeba encystation [42]. Encystation-mediating serine protease (EMSP) was expressed only in Acanthamoeba encystation and PMSF or siRNA knockdown of EMSP transcripts substantially reduced the formation of mature cysts. The action of serine proteases also may be critical for other parasites that undergo encystation. AEBSF is also a non-selective inhibitor of proteasome serine protease activity [86]. In a recent proteomic study [87], two proteasome subunits (GL50803_15099 and GL50803_86683) were immunolocalized to the cytoplasmic side of the ESV membrane in early encystation and the authors proposed that they might assist in the development and maturation of ESV cargo via quality control. In this study, 80 μM AEBSF did not inhibit encystation. It is possible that higher concentrations of AEBSF may affect the Giardia proteasomes.

Giardia encystation is a complex and coordinated transformation that occurs gradually with both early and late phases (Rev. [88-90]). Early stages of encystation include the up-regulation of the known CWP (CWP1-3, HCNCp) transcripts, the increased translation and accumulation of the CWP proteins, and genesis of ESV where the CWPs are concentrated and mature until they are exported to form the cyst wall. CWP2 processing by CP2 [9] in the ESV is thought to occur just before deposition of the mature insoluble CW fibrils. ESCP also is reported to be involved [8] in CWP2 processing. Therefore, we asked if AEBSF affects transcription, translation, or processing of the CWPs. Immunoblots of CWP1 and 2 expressions following 42 h exposure of parasites to AEBSF showed a dose-dependent reduction in full-length CWP1 and 2 (Fig. 7A and B, respectively). However, we did not detect a specific defect in CWP2 processing (Fig. 7B), indicating that CP2 remains active during inhibition of the serine proteases. We also found that the abundance of CP2 and CWP3 proteins was not affected by AEBSF (not shown), suggesting that AEBSF targets a subset of giardial encystation proteins. Interestingly, expression of AU1-tagged gSPC protein itself was inhibited strongly by AEBSF (Fig. 7C). This inhibition of protein translation is likely not due to inhibition of transcription, which occurred during bestatin inhibition of Giardia encystation [17]. Our qPCR results did not detect any significant (>2-fold) decreases in the steady state levels of mRNA of the profiled encystation genes with AEBSF present in encysting media, including gSPC itself (1.07-fold for gSPC; 1.44-fold CWP1, 1.28-fold CWP2, 1.21-fold CWP3, 1.55-fold HCNCp). These results point to a selective process that either targets the translation machinery to reduce translation efficiency or one that enhances degradation of CWP1, CWP2, and gSPC proteins in the presence of AEBSF.

Figure 7.

AEBSF inhibits expression of encystation proteins CWP1, CWP2, and gSPC. Western blot analysis showed that both CWP1 (A) and full-length CWP2 (B) expression are reduced at 42 h encystation in the presence of 2 or 4 mM AEBSF (lanes “2”, “4”) compared to the inhibitor-free control (“0”). AEBSF concentrations as low as 2 mM (lane “2”) nearly abolish AU1-tagged gSPC expression (C) by 21 h encystation.

We also tested the role of AEBSF sensitive proteases during Giardia excystation. Since AEBSF inhibits the trypsin needed to excyst G. lamblia, we used a trypsin-free alternative protocol for excystation of fecal G. muris cysts [24, 61]. Excystation of G. muris cysts with 3 mM AEBSF was inhibited by 77.23 ± 12.96 % (SD; N=3) compared to the untreated control. This strongly suggests that at least one serine protease is required for giardial excystation. Additionally, since gSPC is the most abundant WGA-reactive glycosylated cyst protein [30] it is possible that the inhibition of excystation with the exogenous lectin WGA [91] may inactivate gSPC and consequently ablate excystation. Serine protease activity also has been documented to play a role in other protozoan parasite excystation [92, 93].

The target substrate(s) of endogenous gSPC in Giardia encystation remains elusive. Potential candidates include HCNCp [7] or gGSP [13], as well as gSPC itself, as they are all found within the ESV and are processed only in encystation. Although we could not detect the AU1-tagged gSPC after excystation, it remains possible that serine protease(s) may assist in degrading the cyst wall or possibly aiding in initial binding of excyzoites to mucus or enterocytes [81]. It is clear is that several classes of protease play different roles in giardial differentiation. While cysteine proteases are the most abundant catalytic family, it is now evident that they are not the only players in Giardia s life cycle and that serine proteases are crucial in encystation and excystation as well. Although AEBSF clearly inhibits giardial encystation and excystation, and we detected only a single sensitive enzyme, further studies are needed to determine whether gSPC is the specific target.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1. Giardia degradome. Peptidase families are color-coded: yellow: aspartic; light green: cysteine; lime: metallo; orange: serine; pink: threonine; light blue: unknown. Non-peptidase homologues are shaded in grey.

Supplemental Table 2. Other potential giardial protease genes with low confidence. Peptidase families are color-coded as in Table S1.

Supplemental Table 3. Comparison of the WB C6 degradome to GSM and P15 genomes.

Supplemental Table 4. Giardia transcriptome of the degradome. Peptidase families are color-coded as in Table S1.

Supplemental Table 5. Protease genes with significant variation in the Giardia life cycle (R-value ≥ 8). Peptidase families are color-coded as in Table S1.

Supplemental Figure 1. Amino acid alignment of WB/C6, P15, and GSM gSPC homologs.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Drs. Sharon Reed (UCSD) and Alex Strongin (Burnham Institute) for critically reading the manuscript and for their helpful suggestions. We thank Drs. Kelly DuBois, James McKerrow, and Mohammed Sajid (UCSF) for providing the anti-CP2 polyclonal antibody. Many thanks to Mattias Andersson and Christine Le from the L. Eckmann laboratory (UCSD) for G. muris fecal cysts for our studies. The authors are grateful to Sarah Williams (UCSD) for her skilled technical assistance and to Inge Van Hoven for her help with Blast searches. BJD, MAG, QL, DSR, TL, CL, and FDG were supported by NIH grants R01 AI042488, UAI075527, DK35108 and AI051687. AJS was supported by NIH training grant T32 DK007202. AGM was supported by NIH grant AI51089 and by the Marine Biological Laboratory s Program in Global Infectious Diseases, funded by the Ellison Medical Foundation. Computational resources were provided by the Josephine Bay Paul Center for Comparative Molecular Biology and Evolution (Marine Biological Laboratory) through funds provided by the W.M. Keck Foundation and the G. Unger Vetlesen Foundation to M. Sogin.

Abbreviations

- AEBSF

4-(2-Aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride

- CP2

cysteine protease 2

- CW

cyst wall

- CWG

cyst wall glycopolymer

- CWPs

cyst wall proteins

- ESVs

encystation-specific secretory vesicles

- gSPC

giardial subtilisin-like proprotein convertase

- HCNCp

high cysteine non-variant cyst protein

- SPC

subtilisin-like proprotein convertase

- SAGE

serial analysis of gene expression

- WGA

wheat germ agglutinin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adam RD. Biology of Giardia lamblia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:447–75. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.3.447-475.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang DB, White AC. An updated review on Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35:291–314. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lauwaet T, Davids BJ, Reiner DS, Gillin FD. Encystation of Giardia lamblia: a model for other parasites. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:554–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun CH, McCaffery JM, Reiner DS, Gillin FD. Mining the Giardia lamblia genome for new cyst wall proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21701–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mowatt MR, Lujan HD, Cotten DB, et al. Developmentally regulated expression of a Giardia lamblia cyst wall protein gene. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:955–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lujan HD, Mowatt MR, Conrad JT, et al. Identification of a novel Giardia lamblia cyst wall protein with leucine-rich repeats. Implications for secretory granule formation and protein assembly into the cyst wall. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29307–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davids BJ, Reiner DS, Birkeland SR, et al. A new family of giardial cysteine-rich non-VSP protein genes and a novel cyst protein. PLoS One. 2006;1:e44. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Touz MC, Nores MJ, Slavin I, et al. The activity of a developmentally regulated cysteine proteinase is required for cyst wall formation in the primitive eukaryote Giardia lamblia. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8474–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DuBois KN, Abodeely M, Sakanari J, et al. Identification of the major cysteine protease of Giardia and its role in encystation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18024–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802133200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karr CD, Jarroll EL. Cyst wall synthase: N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase activity is induced to form the novel N-acetylgalactosamine polysaccharide in the Giardia cyst wall. Microbiology. 2004;150:1237–43. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26922-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slavin I, Saura A, Carranza PG, et al. Dephosphorylation of cyst wall proteins by a secreted lysosomal acid phosphatase is essential for excystation of Giardia lamblia. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;122:95–8. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reiner DS, McCaffery JM, Gillin FD. Reversible interruption of Giardia lamblia cyst wall protein transport in a novel regulated secretory pathway. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:459–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Touz MC, Gottig N, Nash TE, Lujan HD. Identification and characterization of a novel secretory granule calcium-binding protein from the early branching eukaryote Giardia lamblia. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50557–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202558200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortega-Barria E, Ward HD, Evans JE, Pereira ME. N-acetyl-D-glucosamine is present in cysts and trophozoites of Giardia lamblia and serves as receptor for wheatgerm agglutinin. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1990;43:151–65. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(90)90141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarroll EL, Manning P, Lindmark DG, et al. Giardia cyst wall-specific carbohydrate: evidence for the presence of galactosamine. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;32:121–31. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKerrow JH, Rosenthal PJ, Swenerton R, Doyle P. Development of protease inhibitors for protozoan infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:668–72. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328315cca9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Touz MC, Nores MJ, Slavin I, et al. Membrane-associated dipeptidyl peptidase IV is involved in encystation-specific gene expression during Giardia differentiation. Biochem J. 2002;364:703–10. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Carvalho TB, David EB, Coradi ST, Guimaraes S. Protease activity in extracellular products secreted in vitro by trophozoites of Giardia duodenalis. Parasitol Res. 2008;104:185–90. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1185-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coradi ST, Guimaraes S. Giardia duodenalis: protein substrates degradation by trophozoite proteases. Parasitol Res. 2006;99:131–6. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-0124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jimenez JC, Uzcanga G, Zambrano A, et al. Identification and partial characterization of excretory/secretory products with proteolytic activity in Giardia intestinalis. J Parasitol. 2000;86:859–62. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0859:IAPCOE]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.David EB, Guimaraes S, Ribolla PE, et al. Partial characterization of proteolytic activity in Giardia duodenalis purified proteins. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2007;49:385–8. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652007000600009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hare DF, Jarroll EL, Lindmark DG. Giardia lamblia: characterization of proteinase activity in trophozoites. Exp Parasitol. 1989;68:168–75. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(89)90094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams AG, Coombs GH. Multiple protease activities in Giardia intestinalis trophozoites. Int J Parasitol. 1995;25:771–8. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(94)00201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward W, Alvarado L, Rawlings ND, et al. A primitive enzyme for a primitive cell: the protease required for excystation of Giardia. Cell. 1997;89:437–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKerrow JH, Caffrey C, Kelly B, et al. Proteases in parasitic diseases. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:497–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sajid M, McKerrow JH. Cysteine proteases of parasitic organisms. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;120:1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(01)00438-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DuBois KN, Abodeely M, Sajid M, et al. Giardia lamblia cysteine proteases. Parasitol Res. 2006;99:313–6. doi: 10.1007/s00436-006-0149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abodeely M, DuBois KN, Hehl A, et al. A contiguous compartment functions as endoplasmic reticulum and endosome/lysosome in Giardia lamblia. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:1665–76. doi: 10.1128/EC.00123-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birkeland SR, Preheim SP, Davids BJ, et al. Transcriptome analyses of the Giardia lamblia life cycle. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2010;174:62–5. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ratner DM, Cui J, Steffen M, et al. Changes in the N-glycome, glycoproteins with Asn-linked glycans, of Giardia lamblia with differentiation from trophozoites to cysts. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1930–40. doi: 10.1128/EC.00268-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seidah NG, Chretien M, Day R. The family of subtilisin/kexin like pro-protein and pro-hormone convertases: divergent or shared functions. Biochimie. 1994;76:197–209. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seidah NG, Day R, Marcinkiewicz M, Chretien M. Precursor convertases: an evolutionary ancient, cell-specific, combinatorial mechanism yielding diverse bioactive peptides and proteins. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;839:9–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seidah NG, Chretien M. Proprotein and prohormone convertases of the subtilisin family Recent developments and future perspectives. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1992;3:133–40. doi: 10.1016/1043-2760(92)90102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fugere M, Day R. Cutting back on pro-protein convertases: the latest approaches to pharmacological inhibition. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rockwell NC, Thorner JW. The kindest cuts of all: crystal structures of Kex2 and furin reveal secrets of precursor processing. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:80–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson ED, VanSlyke JK, Thulin CD, et al. Activation of the furin endoprotease is a multiple-step process: requirements for acidification and internal propeptide cleavage. Embo J. 1997;16:1508–18. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gawlik K, Shiryaev SA, Zhu W, et al. Autocatalytic activation of the furin zymogen requires removal of the emerging enzyme's N-terminus from the active site. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou A, Martin S, Lipkind G, et al. Regulatory roles of the P domain of the subtilisin-like prohormone convertases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11107–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Withers-Martinez C, Jean L, Blackman MJ. Subtilisin-like proteases of the malaria parasite. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wanyiri JW, Techasintana P, O'Connor RM, et al. Role of CpSUB1, a subtilisin-like protease, in Cryptosporidium parvum infection in vitro. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:470–7. doi: 10.1128/EC.00306-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng X, Akiyoshi DE, Widmer G, Tzipori S. Characterization of subtilase protease in Cryptosporidium parvum and C. hominis J Parasitol. 2007;93:619–26. doi: 10.1645/GE-622R1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moon EK, Chung DI, Hong YC, Kong HH. Characterization of a serine proteinase mediating encystation of Acanthamoeba. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1513–7. doi: 10.1128/EC.00068-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barr SC, Warner K. Characterization of a serine protease activity in Sarcocystis neurona merozoites. J Parasitol. 2003;89:385–8. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2003)089[0385:COASPA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yeoh S, O'Donnell RA, Koussis K, et al. Subcellular discharge of a serine protease mediates release of invasive malaria parasites from host erythrocytes. Cell. 2007;131:1072–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morrison HG, McArthur AG, Gillin FD, et al. Genomic minimalism in the early diverging intestinal parasite Giardia lamblia. Science. 2007;317:1921–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1143837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith PD, Gillin FD, Kaushal NA, Nash TE. Antigenic analysis of Giardia lamblia from Afghanistan, Puerto Rico, Ecuador, and Oregon. Infect Immun. 1982;36:714–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.2.714-719.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun CH, Palm D, McArthur AG, et al. A novel Myb-related protein involved in transcriptional activation of encystation genes in Giardia lamblia. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:971–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rawlings ND, Morton FR. The MEROPS batch BLAST: a tool to detect peptidases and their non-peptidase homologues in a genome. Biochimie. 2008;90:243–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lopez R, Silventoinen V, Robinson S, et al. WU-Blast2 server at the European Bioinformatics Institute. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3795–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eddy SR. A probabilistic model of local sequence alignment that simplifies statistical significance estimation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008;4:e1000069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Finn RD, Tate J, Mistry J, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D281–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barrett AJ, Rawlings ND. 'Species' of peptidases. Biol Chem. 2007;388:1151–7. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rawlings ND, Morton FR, Kok CY, et al. MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D320–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palm D, Weiland M, McArthur AG, et al. Developmental changes in the adhesive disk during Giardia differentiation. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;141:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stekel DJ, Git Y, Falciani F. The comparison of gene expression from multiple cDNA libraries. Genome Res. 2000;10:2055–61. doi: 10.1101/gr.gr-1325rr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weiland ME, Palm JE, Griffiths WJ, et al. Characterisation of alpha-1 giardin: an immunodominant Giardia lamblia annexin with glycosaminoglycan-binding activity. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33:1341–51. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Touz MC, Lujan HD, Hayes SF, Nash TE. Sorting of encystation-specific cysteine protease to lysosome-like peripheral vacuoles in Giardia lamblia requires a conserved tyrosine-based motif. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6420–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singer SM, Yee J, Nash TE. Episomal and integrated maintenance of foreign DNA in Giardia lamblia. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;92:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Davids BJ, Mehta K, Fesus L, et al. Dependence of Giardia lamblia encystation on novel transglutaminase activity. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;136:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boucher SE, Gillin FD. Excystation of in vitro-derived Giardia lamblia cysts. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3516–22. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3516-3522.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Feely DE, Gardner MD, Hardin EL. Excystation of Giardia muris induced by a phosphate-bicarbonate medium: localization of acid phosphatase. J Parasitol. 1991;77:441–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Campbell JD, Faubert GM. Recognition of Giardia lamblia cyst-specific antigens by monoclonal antibodies. Parasite Immunol. 1994;16:211–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1994.tb00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hussein EM, Dawoud HA, Salem AM, Atwa MM. Antiparasitic activity of cystine protease inhibitor E-64 against Giardia lamblia excystation in vitro and in vivo. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2009;39:111–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smid O, Matuskova A, Harris SR, et al. Reductive evolution of the mitochondrial processing peptidases of the unicellular parasites trichomonas vaginalis and giardia intestinalis. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000243. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marques AJ, Palanimurugan R, Matias AC, et al. Catalytic mechanism and assembly of the proteasome. Chem Rev. 2009;109:1509–36. doi: 10.1021/cr8004857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cai SY, Babbitt RW, Marchesi VT. A mutant deubiquitinating enzyme (Ubp-M) associates with mitotic chromosomes and blocks cell division. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2828–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Quesada V, Diaz-Perales A, Gutierrez-Fernandez A, et al. Cloning and enzymatic analysis of 22 novel human ubiquitin-specific proteases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Page MJ, Di Cera E. Evolution of peptidase diversity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30010–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804650200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Monis PT, Andrews RH, Mayrhofer G, Ey PL. Molecular systematics of the parasitic protozoan Giardia intestinalis. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:1135–44. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abe N, Read C, Thompson RC, Iseki M. Zoonotic genotype of Giardia intestinalis detected in a ferret. J Parasitol. 2005;91:179–82. doi: 10.1645/GE-3405RN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Franzen O, Jerlstrom-Hultqvist J, Castro E, et al. Draft genome sequencing of giardia intestinalis assemblage B isolate GS: is human giardiasis caused by two different species? PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000560. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tucker M, Han M. Muscle cell migrations of C. elegans are mediated by the alpha-integrin INA-1, Eph receptor VAB-1, and a novel peptidase homologue MNP-1. Dev Biol. 2008;318:215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Klemba M, Goldberg DE. Biological roles of proteases in parasitic protozoa. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:275–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.090501.145453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Siezen RJ, Leunissen JA. Subtilases: the superfamily of subtilisin-like serine proteases. Protein Sci. 1997;6:501–23. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Knodler LA, Noiva R, Mehta K, et al. Novel protein-disulfide isomerases from the early-diverging protist Giardia lamblia. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29805–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lopez AB, Sener K, Jarroll EL, van Keulen H. Transcription regulation is demonstrated for five key enzymes in Giardia intestinalis cyst wall polysaccharide biosynthesis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;128:51–7. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(03)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gerwig GJ, van Kuik JA, Leeflang BR, et al. The Giardia intestinalis filamentous cyst wall contains a novel beta(1-3)-N-acetyl-D-galactosamine polymer: a structural and conformational study. Glycobiology. 2002;12:499–505. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwf059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chandra NR, Prabu MM, Suguna K, Vijayan M. Structural similarity and functional diversity in proteins containing the legume lectin fold. Protein Eng. 2001;14:857–66. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.11.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fugere M, Limperis PC, Beaulieu-Audy V, et al. Inhibitory potency and specificity of subtilase-like pro-protein convertase (SPC) prodomains. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7648–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rodriguez-Fuentes GB, Cedillo-Rivera R, Fonseca-Linan R, et al. Giardia duodenalis: analysis of secreted proteases upon trophozoite-epithelial cell interaction in vitro. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;101:693–6. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762006000600020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Powers JC, Asgian JL, Ekici OD, James KE. Irreversible inhibitors of serine, cysteine, and threonine proteases. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4735–4736. doi: 10.1021/cr010182v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Conseil V, Soete M, Dubremetz JF. Serine protease inhibitors block invasion of host cells by Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1358–61. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Withers-Martinez C, Saldanha JW, Ely B, et al. Expression of recombinant Plasmodium falciparum subtilisin-like protease-1 in insect cells. Characterization, comparison with the parasite protease, and homology modeling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29698–709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Poole CB, Jin J, McReynolds LA. Cloning and biochemical characterization of blisterase, a subtilisin-like convertase from the filarial parasite, Onchocerca volvulus. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36183–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]