Abstract

Background

A specific diagnosis of a lower respiratory viral infection is often difficult despite frequent clinical suspicion. This low diagnostic yield may be improved by use of sensitive detection methods and biomarkers.

Methods

We investigated the prevalence, clinical predictors and inflammatory mediator profile of respiratory viral infection in serious acute respiratory illness. Sequential bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluids from all patients hospitalized with acute respiratory illness over 12 months (n=283) were tested for the presence of 17 respiratory viruses by multiplex PCR assay and for newly-discovered respiratory viruses (bocavirus, WU and KI polyomaviruses) by single-target PCR. BAL samples also underwent conventional testing (direct immunoflorescence and viral culture) for respiratory virus at the clinician’s discretion. 27 inflammatory mediators were measured in subset of the patients (n=64) using a multiplex immunoassay.

Results

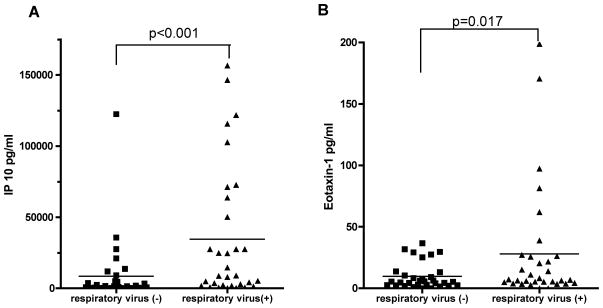

We detected 39 respiratory viruses in 37 (13.1% of total) patients by molecular testing, including rhinovirus (n=13), influenza virus (n=8), respiratory syncytial virus (n=6), human metapneumovirus (n=3), coronavirus NL63 (n=2), parainfluenza virus (n=2), adenovirus (n=1), and newly-discovered viruses (n=4). Molecular methods were 3.8-fold more sensitive than conventional methods. Clinical characteristics alone were insufficient to separate patients with and without respiratory virus. The presence of respiratory virus was associated with increased levels of interferon-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP -10)(p<0.001) and eotaxin-1 (p=0.017) in BAL.

Conclusions

Respiratory viruses can be found in patients with serious acute respiratory illness by use of PCR assays more frequently than previously appreciated. IP-10 may be a useful biomarker for respiratory viral infection.

Keywords: Respiratory virus infection, Bronchoalveolar Lavage, IP-10 (CXCL10), Biological Markers

Introduction

Lower respiratory tract infection is a leading cause of hospitalization 1 2. Because it can cause high morbidity and mortality, especially in immunocompromized hosts 3–5, prompt diagnosis is crucial for optimal clinical management and avoidance of unnecessary antibiotic use. Analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid is often used to assist the diagnosis in patients with unexplained acute respiratory illness. However, in current practice, an etiological agent is often not found 6 7, even in patients whose clinical presentation strongly suggest a viral etiology. Despite frequent clinical suspicion, a specific viral diagnosis is rarely made. The failure to detect viral etiologies could have multiple explanations, including difficulty in differentiating respiratory virus infection from other acute respiratory infections or diseases, lack of sensitivity of conventional detection methods (direct immunoflorescence and viral culture), and existence of unrecognized infectious agents. Moreover, even when respiratory viruses are detected in the respiratory tract, it may be difficult to define their contribution to the patient’s illness. Improvement in the diagnosis of acute respiratory viral infection may be achieved by the use of sensitive diagnostic methods or by the use of biomarkers associated with respiratory viral infection. Previous studies have shown that molecular-based methods may improve the sensitivity of respiratory virus detection 8–11. However, some of these studies were retrospective in design, reporting enhanced detection of respiratory viruses in BAL samples, without performing a comprehensive clinical evaluation to assess the accuracy of the diagnosis. Moreover, previous studies did not address simultaneously the potential diagnostic utility of measuring inflammatory mediators in BAL fluid. Accordingly, we hypothesized that respiratory viruses would be found commonly in BAL fluid, and that the profile of inflammatory mediators would also be useful for making a diagnosis of lower respiratory virus infection in hospitalized patients. Here we applied comprehensive molecular testing for respiratory viruses and a multiplex immunoassay to measure multiple inflammatory mediators in BAL fluid from patients hospitalized with acute respiratory illness to establish an improved diagnostic approach.

Methods

Patients and BAL collection

We included all adult patients hospitalized at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri who underwent bronchoscopy with microbiological assessment of their BAL for the diagnosis of acute respiratory illness from October 2005 to October 2006. A total of 283 sequential BAL samples were prospectively collected. Patients were excluded only for the following reasons: outpatient status, bronchoscopy performed immediately post surgery or trauma, and collection of only bronchial wash samples. For patients who underwent a repeat bronchoscopy within 3 weeks of a first procedure, only the earlier sample was included. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was performed by pulmonary or critical care physicians based on clinical judgment independent of this study. BAL was performed by instilling 100–150 ml of sterile saline into the distal airways either at the site of radiographic abnormality or the right middle lobe. BAL fluid samples were stored at 4°C in the Microbiology Laboratory after routine testing and were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. The study was approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office.

Respiratory virus detection

Viral RNA extraction

Viral nucleic acid extraction was performed with the Qiagen BioRobot M48 instrument using the MagAttract Virus Mini M48 kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). A 200μl aliquot of unprocessed BAL fluid was used and eluted to a final volume of 100μl. A fixed amount of inactivated mouse hepatitis virus was included in each BAL sample during the extraction process to assure quality of the nucleic acid extraction.

Conventional microbe and viral testing

All BAL samples underwent standard bacterial culture at the hospital Microbiology laboratory. Selected samples were submitted to the hospital virology lab for virus detection according to physician judgment independent of this study. Those samples (n = 197) underwent conventional viral testing (direct immunofluorescence assay and viral culture), as described previously 12.

Multiplex PCR for respiratory viruses

The Multicode-PLx Respiratory Virus Panel (Multicode-PLx RVP; EraGen, Madison, WI) was used for detection of influenza virus (type A and B), respiratory syncytial virus (type A and B), parainfluenza virus (types 1–4a,b), human metapneumovirus, adenovirus (groups B, C, E), coronavirus (OC43, NL 63, 229E), and rhinovirus as previously described 13 14.

Single target quantitative real-time PCR

Single target quantitative real-time PCR (RT-PCR) was used for detection of bocavirus, and the newly described human polyomaviruses KI virus (KIV) and WU virus (WUV). Further details are provided in the supplement.

Multiplex immunoassay for inflammatory mediators

We measured the levels of multiple inflammatory mediators in the 32 samples that were positive for a respiratory virus, excluding 3 samples positive solely for bocavirus, WUV, or KIV and 2 samples for which sample quality was suboptimal for this analysis. In addition, we randomly selected 32 BAL samples without a respiratory virus as a control group, using a computer based random selector (STATA, StataCorpLP, TX). The demographic characteristics of the patients who were randomly selected were not different from those who were not selected (data not shown). We analyzed cell-free supernatants in a multiplex flow cytometry-based assay (BioRad Bio-Plex Human 27 Panel) as previously described 15 16. Further details are provided in the online supplement.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data was expressed as mean±SD (SD: standard deviation), or median (IQR: interquartile range) for non-normally distributed data. Chi-square or the Fisher exact test were used to compare categorical variables. Continuous variables were compared using the unpaired t–test performed on raw values or on log-transformed data if log transformation produced approximately normal distribution. For non-normally distributed data, the Wilcoxon-rank-sum test (Mann-Whitney-U test) was used to compare two groups. Receiver operating curve analysis was performed to evaluate the optimal cutoff level of each inflammatory mediator to differentiate the groups with respiratory virus and without respiratory virus. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. These analyses were performed using the STATA version 9 for Macintosh (StataCorp, College station, TX).

Results

Patient characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 283 patients are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients had illness severe enough to require care in an intensive care unit (67.8%) with mechanical ventilation (67.1%) and the overall in-house mortality rate was 25% reflecting the severity of illness in our study population. Nearly half of the patients were immunosupressed, defined by the presence of one of the following: organ transplant recipient, on immunosuppressive medications (including systemic corticosteroids in a dose exceeding 10mg of prednisone per day, or other immunosuppressive medications), receipt of chemotherapy within 12 months or human immunodeficiency virus infection. Almost all were treated with antibiotics for the acute respiratory illness. Most of the patients had underlying conditions: solid organ malignancy was the most common followed by hematologic malignancy and lung transplantation. All patients had abnormal chest radiographs with over 60% showing multifocal or diffuse abnormality. The patient’s respiratory diagnoses assigned by the clinicians were highly variable with the most common diagnosis being pneumonia.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients (n=283)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Mean age (years ± SD) | 55±15 |

| Male | 161 (56.9) |

| ICU | 192 (67.8) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 190 (67.1) |

| Immunosuppressive state | 131 (46.3) |

| Antibiotic treatment | 271 (95.8) |

| Median hospital length of stay (median, iqr) | 19 (10,34) |

| In hospital mortality (%) | 71 (25.1) |

| Underlying disease/condition | |

| Solid organ malignancy | 40 (14.1) |

| Hematologic malignancy | 39 (13.8) |

| Lung transplantation | 37 (13.1) |

| Lung disease | 34 (12.0) |

| Other solid organ transplantation | 13 (4.6) |

| Autoimmune disease | 13 (4.6) |

| HIV | 11 (3.9) |

| Others | 78 (27.6) |

| No underlying disease | 14 (5.3) |

| Uncertain | 4 (1.4) |

| Chest radiograph | |

| Any abnormality | 283 (100) |

| Multifocal infiltrates or consolidation | 99 (35.0) |

| Diffuse infiltrates | 77 (27.2) |

| Respiratory diagnosis | |

| Pneumonia | 153 (54.1) |

| Interstitial lung diseases | 30 (10.6) |

| ARDS | 19 (6.7) |

| Lung Transplant complication/rejection | 13 (4.6) |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage | 9 (3.2) |

| Cardiac decompensation | 8 (2.8) |

| Malignancy | 8 (2.8) |

| Others | 43 (15.2) |

Definition of abbreviations: BAL=bronchoalveolar lavage, ICU=intensive care unit, HIV=human immunodeficiency virus, SD=standard deviation, iqr=interquartile range, ARDS=Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Detection of respiratory viruses by molecular testing

39 viruses were detected in 37 (13.1%) patients by molecular testing (Table 2). There were 2 cases of dual infection. Rhinovirus was the most frequently found virus, followed by influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and human metapneumovirus (MPV). KI virus was found in two samples and human bocavirus and WU virus were each found in one. Rhinovirus was found year-around, but the other viruses were found mainly during the winter and spring months (February to April). (Figure E1)

Table 2.

Respiratory viruses detected in BAL fluid

| Respiratory Virus | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Rhinovirus | 13 (4.6) |

| Influenza A or B | 8 (2.8) |

| RSV | 6 (2.1) |

| MPV | 3 (1.1) |

| Coronavirus NL63 | 2 (0.7) |

| Parainfluenza | 2 (0.7) |

| KI virus* | 2 (0.7) |

| Adenovirus | 1 (0.4) |

| Bocavirus* | 1 (0.4) |

| WU virus* | 1 (0.4) |

| Total | 39 (13.1)† |

Number is parentheses represent the percent of virus positive cases in the total study population (n=283). Definition of abbreviations: BAL=bronchoalveolar lavage, RSV=respiratory syncytial virus, MPV=metapneumovirus

2 cases of dual infection (parainfluenza and influenza B, rhinovirus and KI virus) were included in the total of each virus.

Detected by single target PCR. The rest of the viruses were detected by Multicode-PLX

Yield of respiratory virus detection by molecular testing

To directly compare molecular and conventional viral testing, we analyzed BAL samples for which both molecular and conventional methods were performed (n=197). A total of 31 respiratory viruses were found by either type of testing. Molecular testing detected all 31 viruses (100%), while conventional methods detected only 8 viruses (26%), corresponding to a 3.8-fold increase in yield by molecular testing. This increased yield resulted from both the detection of newly-discovered viruses not found by conventional testing (MPV, coronaviruses, KI virus and WU virus), and from enhanced sensitivity for “classic” respiratory viruses (Table 3).

Table 3.

Respiratory viruses detected in BAL samples (n = 197) tested by both molecular and conventional methods

| Virus | Detection method | Total detected | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular | DFA/culture | ||

| Rhinovirus | 10 | 2 | 10 |

| Influenza virus | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| RSV | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| MPV | 3 | not tested | 3 |

| Coronavirus NL63 | 2 | not tested | 2 |

| Parainfluenza virus | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| KI virus | 2 | not tested | 2 |

| Adenovirus | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| WU virus | 1 | not tested | 1 |

| Total (Yield%) | 31 (100%) | 8 (26%) | 31 |

Definition of abbreviations: DFA=direct immunoflorescence assay, BAL=bronchoalveolar lavage, RSV=respiratory syncytial virus, MPV=human metapneumovirus,

Clinical characteristics of the patients with respiratory virus

To determine if there were clinical features that could identify illnesses associated with a respiratory virus, we compared demographic features, clinical characteristics and disease severity measurements in cases with a respiratory virus (n=34) to those without a respiratory virus (n=246) (Table 4). 3 BALs with human bocavirus, WU, and KI virus alone were excluded from this analysis since the clinical role of these viruses was not established at the time of this manuscript submission. The overall proportions of immunosuppressed patients were not different, but there were significantly more lung transplant recipients in the respiratory virus-positive group (23.5% vs. 11.4%, p=0.047). Interestingly, the respiratory virus-positive group had multifocal infiltrates or consolidation more frequently (50.0% vs. 33.3%) and diffuse infiltrates less frequently (11.8% vs. 24.4%). Respiratory viruses were found significantly less frequently during the summer months (8.8% vs. 21.9%, p=0.042). No measures of severity were different between the two groups. The proportions of patients receiving antibacterial or anti-fungal agents were also similar. Overall, there were no clinically useful characteristics that distinguished patients with and without a respiratory virus.

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics and disease severity in patients with and without respiratory virus

| Clinical characteristics | Respiratory virus (+) n=34 | Respiratory virus (−) n=246 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline features | |||

| Mean age | 55.7±14.0 | 55.0±15.1 | 0.800 |

| Age>65 | 8 (23.5) | 63 (25.6) | 0.794 |

| Male, n (%) | 20 (58.8) | 139 (56.5) | 0.798 |

| Immunosuppressive state | 20 (58.8) | 110 (44.7) | 0.122 |

| Lung transplant recipient | 8 (23.5) | 28 (11.4) | 0.047 |

| Hematologic malignancy | 5 (14.7) | 34 (13.8) | 0.889 |

| Located Medical service | 28 (82.4) | 182 (74.0) | 0.291 |

| Chest Radiograph | |||

| Multifocal infiltrates or consolidation | 17 (50.0) | 82 (33.3) | 0.057 |

| Diffuse infiltrates | 4 (11.8) | 72 (29.3) | 0.032 |

| Focal findings | 4 (11.8) | 23 (9.4) | 0.655 |

| BAL testing | |||

| BAL done > 7 days after hospitalization | 8 (23.5) | 81 (32.9) | 0.270 |

| Sample sent for routine viral detection | 7 (20.6) | 78 (31.7) | 0.186 |

| Microbiological findings BAL fluid | |||

| No microorganism detected | 12 (35.3) | 107 (43.5) | 0.365 |

| Bacterial/fungal pathogen detected | 13 (38.2) | 84 (34.2) | 0.639 |

| Seasonality | |||

| Winter-spring season (Nov-April) | 24 (70.6) | 154 (62.6) | 0.364 |

| Summer months (Jun–Aug) | 3 (8.8) | 60 (24.4) | 0.042 |

| Severity | |||

| In hospital mortality | 7 (20.6) | 64 (26.0) | 0.495 |

| On mechanical ventilation | 21 (61.8) | 167 (68.2) | 0.456 |

| Requiring oxygen | 31 (91.2) | 230 (93.9) | 0.548 |

| Days of ICU stay (median, IQR) | 9 (0, 22) | 18 (0, 24) | 0.371 |

| Days of hospitalization (median, IQR) | 16 (99, 30) | 19.5 (11, 35) | 0.237 |

| Any use of antibiotics | 34 (100) | 236 (96.3) | 0.256 |

| Days of antibiotic use (median, IQR) | 13 (8, 28) | 15 (7, 28) | 0.655 |

| Any use of antifungal agents | 18 (52.9) | 121 (49.2) | 0.682 |

Values are number (percent of column total), mean ±SD, or median (IQR: interquartile range) for continuous variables.

Inflammatory mediator profile

Since clinical characteristics did not appear to be sufficient to identify patients with respiratory virus infection, we evaluated the inflammatory mediator profile in BAL fluid. As shown in Table 5, measurable levels were present for 20 out of 27 inflammatory mediators. Among these, interferon-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP -10) and eotaxin-1 were present at significantly higher levels in patients in whom a respiratory virus was detected (IP-10: p<0.001, eotaxin-1: p=0.017) (Figure 1). When examined by virus, no particular virus type was individually associated with high levels of IP-10 or eotaxin-1 (data not shown). A positive correlation was seen between eotaxin-1 and IP-10 concentrations (r=0.56, p<0.0001).

Table 5.

Inflammatory mediator concentration in BAL fluid

| Mediator (pg/ml) | Respiratory virus (+) n=32 | Respiratory virus (−) n=32 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1 | 6.35 (3.09, 31.22) | 6.58 (1.24, 36.65) | 0.552 |

| IL-1a | 534.55 (292.43, 1753.36) | 524.84 (326.94, 1040.44) | 0.501 |

| IL-2 | not detected | not detected | |

| IL-4 | not detected | not detected | |

| IL-5 | not detected | not detected | |

| IL-6 | 22.79 (4.09, 194.46) | 32.46 (5.16, 310.08) | 0.981 |

| IL-7 | 1.61 1.19, 2.10) | 1.66 (1.36, 2.78) | 0.390 |

| IL-8 | 360.61 (161.00, 1592.96) | 204.85 (68.92, 1264.6) | 0.464 |

| IL-9 | 7.98 (2.68, 14.44) | 3.24 (0.63, 9.61) | 0.085 |

| IL-10 | 4.00 (2.49, 7.91) | 2.945 (1.33, 4.64) | 0.170 |

| IL-12 | 5.45 (3.31, 9.45) | 4.25 (2.04, 5.94) | 0.065 |

| IL-13 | 1.856 (1.24, 3.18) | 1.75 (0.975, 2.85) | 0.435 |

| IL-15 | 1.82 (0.07, 8.94) | 0.915 (0.2, 2.88) | 0.363 |

| IL-17 | 6.20 (0, 24.48) | not detected | |

| Basic FGF | not detected | not detected | |

| Eotaxin-1 | 6.98 (4.71, 25.94) | 5.39 (2.44, 11.78) | 0.017 |

| G-CSF | 23.55 (7.85, 97.77) | 14.26 (6.45, 76.03) | 0.421 |

| GM-CSF | not detected | not detected | |

| IFN-g | 12.21 (2.95, 34.84) | 9.81 (0.99, 19.57) | 0.144 |

| IP-10 | 8902.33 (2059.07, 57015.20) | 1246.82 (305.73, 4811.82) | <0.001 |

| CCL2/MCP-1 | 259.50 (61.71, 1583.27) | 240.03 (19.33, 578.28) | 0.296 |

| CCL3/MIP-1a | not detected | not detected | |

| CCL4/MIP-1b | 60.55 (29.16, 179.11) | 44.00 (27.72, 87.79) | 0.115 |

| PDGF-BB | 12.94 (6.38, 20.60) | 11.80 (4.81, 19.00) | 0.838 |

| CCL5/RANTES | 66.39 (25.41, 119.57) | 31.59 (11.23, 97.15) | 0.385 |

| TNF-a | 9.98 (0, 24.57) | 1.63 (0, 7.07) | 0.108 |

| VEGF | 36.42 (15.13, 80.55) | 35.37 (12.25, 70.86) | 0.995 |

Values were expressed as median (25%IQR, 75%IQR). “not detected” indicates level beneath the lower limit of detection of the assay. Definition of abbreviations: IQR=interquartile range.

Figure 1. Levels of IP-10 and eotaxin-1 in BAL.

IP-10 (A) and eotaxin-1 (B) concentration in BAL sample in patients with respiratory virus (solid square) and without respiratory virus infection (solid triangle). IP-10 and eotaxin-1 were significantly increased in the respiratory virus-positive group among the 27 inflammatory mediators tested by multiplex flow-cytometry based assay. Horizontal lines indicate the mean levels in each group.

IP-10 and eotaxin-1 as predictors of respiratory virus detection

We next investigated whether the concentration of IP-10 or eotaxin-1 in BAL could be used to differentiate patients with respiratory virus from patients without respiratory virus in BAL in the subpopulation in which the inflammatory mediators were measured (n=64). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to determine the optimal cutoff values. The optimal cutoff value for IP-10 was 1700 pg/ml, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.76 (95%CI, 0.64–0.87). Defining an IP-10 level greater than or equal to this value as positive resulted in a sensitivity of 81.3% (95%CI, 71.7–90.7) and specificity of 59.4% (95%CI, 47.3–71.4), with a positive likelihood ratio (LR) of 2.00 and negative LR of 0.32. ROC analysis for eotaxin-1 concentration in BAL revealed that the optimal cutoff value was 5pg/ml, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.63 (95%CI, 0.50–0.77). Defining an eotaxin-1 level greater than or equal to this value as positive resulted in a sensitivity of 75.0% (95%CI, 64.4–85.6) and specificity of 46.9% (95%CI, 34.6–59.1), a positive LR of 1.41 and a negative LR of 0.53, indicating that eotaxin-1 level was less predictive of the presence of a respiratory virus compared to IP-10 level.

Discussion

In this study, we have made several important findings with regard to the role of respiratory viruses in adult patients with serious acute respiratory illness: 1) highly sensitive molecular testing detected a respiratory virus in 13% of hospitalized patients who underwent bronchoscopy for acute respiratory illness, 2) these patients could not be accurately identified by their clinical features alone and were usually not identified by conventional viral diagnostic testing, and 3) two inflammatory mediators, IP-10 and eotaxin-1 were present at elevated levels in BAL of patients with respiratory virus.

By using highly-sensitive molecular methods, we were able to assess the prevalence of lower respiratory virus infection in the inpatient adult hospital setting in a comprehensive manner. The frequency of respiratory viral infection in the present study was similar to that in a recent study of hospitalized adults in University hospitals in Switzerland, in which respiratory viruses were detected by molecular methods in 17% ofBAL samples 17. In that study, coronavirus was the most common virus detected, followed by rhinovirus and parainfluenza virus. In contrast, rhinovirus was the most common respiratory virus detected in our study and coronaviruses were detected infrequently. Rhinovirus has traditionally been thought to cause mainly upper airway disease, but our frequent recovery of rhinovirus from the lower respiratory tract is in agreement with recent studies that support the fact that rhinovirus is also an important lower respiratory tract pathogen 18 19. However, it is also important to note that in our population of hospitalized patients with serious acute respiratory illness, the clinical significance of rhinovirus infection appeared to be less clear than that of “traditional” respiratory viruses such as influenza virus and RSV. The differences in viruses detected between the present study and the Swiss study could be due to geographical or seasonal differences, or to the fact that our study was directed at hospitalized population with more severe disease. We also did not test for coronavirus HKU1. We did test for other newly described viruses including human bocavirus and the WU and KI polyomaviruses, and found that these viruses were uncommon in adults with serious respiratory illness.

Our careful review of the clinical courses of our patients revealed that clinical characteristics alone did not distinguish patients in whom respiratory virus was detected. Likewise, in the Swiss study, most clinical characteristics with the exception of lack of infiltrates on chest x-ray and lack of antibiotic treatment response also did not predict the presence of respiratory virus infection. This difficulty in predicting the presence of respiratory viral infection based on clinical characteristics led us to investigate the use of biomarkers. Recent advances in multiplex assay technology allowed us to simultaneously quantify 27 inflammatory mediators in an unbiased fashion. Using the BioPlex assay, we found that two mediators, IP-10 (also known as CXCL10) and eotaxin-1, were both associated with the presence of respiratory virus. This is the first study of which we are aware that evaluated the concentration of multiple inflammatory mediators in BAL from patients with respiratory virus infection.

IP-10 is a ligand for the CXCR3 receptor, and acts as a chemoattractant for activated Th1 cells, and natural killer cells 20–22. It has been shown to play an important role in the host response to a variety of viral infections including rhinovirus 23, RSV 24 25, herpes simplex virus 26, and hepatitis C virus 27 28. Previous studies have demonstrated that IP-10 is released from cultured human airway epithelial cells in response to rhinovirus 23 and H5N1 influenza infection 29 and is detected in respiratory samples of patients with rhinovirus upper airway infection 23 and RSV bronchiolitis 24. Moreover, recent studies suggest that serum IP-10 level may be an important biomarker for various virus infections. In patients with chronic hepatitis C infection, serum IP-10 level has been shown to predict treatment response 27 28 30. A study of patients with asthma exacerbations suggested that the serum IP-10 level could be a useful biomarker in differentiating virus-induced acute asthma from non virus-induced acute asthma 31. A recent study in patients with COPD showed that serum IP-10 level may be a useful biomarker for rhinovirus induced COPD exacerbation 32. Our study extends these observations to its potential use in the diagnosis of respiratory viral infection in adults with hospitalized with acute respiratory illness. We found that higher levels of IP-10 in BAL were associated with the presence of a respiratory virus indicating that measurement of IP-10 level may be useful to differentiate patients with respiratory virus in BAL, especially in the setting when the conventional methods for viral detection are unrevealing. The other inflammatory mediator that was elevated in patients with respiratory virus infection was eotaxin-1, which was less predictive of the presence of a respiratory virus than was IP-10 level. Eotaxin-1 is a selective chemoattractant for eosinophils, and is often implicated in allergic responses 33. Previous studies have demonstrated that eotaxin-1 is produced by bronchial epithelial cells in response to infection by respiratory viruses including influenza virus 34, and rhinovirus 35, but further investigation is needed to determine the overall role of eotaxin-1 and eosinophils in the host response to viral infection.

The major limitation of this study is that it was not possible to assess the clinical significance of the viruses that were detected. Most of the patients were very ill and had multiple possible explanations for their respiratory illness. Some of the viruses detected, such as influenza A and RSV appeared to be generally pathogenic. The clinical significance of others, such as rhinovirus and the coronaviruses were less certain. The inability to assess the clinical significance of the viruses detected also made it difficult to assess whether the levels of IP-10 and eotaxin-1 correlated with the severity of viral infection. In addition, we were able to measure the inflammatory mediators only in the subgroup of the study population. Most of the viral-positive samples were studied (n=32), but we only studied randomly selected samples (n=32) from the virus-negative group of 286. Even though the main clinical characteristics of the randomly selected population were not different than those who were not selected, the finding of the inflammatory mediators may not be generalizable to the whole study population. ROC analysis was also only performed in the subpopulation.

In summary, this study found that comprehensive molecular testing can detect respiratory viruses in BAL fluid frequently and much more effectively than conventional diagnostic methods in patients hospitalized with acute respiratory illness. Measurement of IP-10 may be a useful biomarker for viral infection although it does not appear that it can be used as a single marker. Further study is needed to confirm our findings and define an appropriate cutoff level for IP-10 in a larger population and also to evaluate its role in assessing the clinical importance in the diagnosis of viral infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David Misselhorn, Mike Henderson, Karen McBride and Jeanette Wipfler for assistance in providing information on bronchoscopic procedures performed, the staff of the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Microbiology Laboratory and St. Louis Children Hospital Virology Laboratory and Ngozi Erondeu for assistance with the collection and storage of BAL samples, Dave Marshall from EraGen Biosciences for performing the PLx Multicode testing, and Jie Zheng, Bill Shannon, Jia Wang for statistical advice.

Funding

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health grant U54 AI057160 to the Midwest Regional Centers of Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases Research (MRCE)

Footnotes

Competing interests

Gregory Storch received consultation fees from Idaho Technology, Diagnostic Hybrids Inc, and Roche Molecular Diagnostics and has received an honorarium from Abbott Laboratories. All other authors have no competing interests to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Copyright license statement

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive license (or non-exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Thorax and any other BMJPGL products and to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our license.

References

- 1.Blasi F, Aliberti S, Pappalettera M, et al. 100 years of respiratory medicine: pneumonia. Respir Med. 2007;101(5):875–81. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.File TM. The epidemiology of respiratory tract infections. Semin Respir Infect. 2000;15(3):184–94. doi: 10.1053/srin.2000.18059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabella N, Rodriguez P, Labeaga R, et al. Conventional respiratory viruses recovered from immunocompromised patients: clinical considerations. Clin Inf Dis. 1999;28:1043–1048. doi: 10.1086/514738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raboni SM, Nogueira MB, Tsuchiya LR, et al. Respiratory tract viral infections in bone marrow transplant patients. Transplantation. 2003;76(1):142–6. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000072012.26176.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garbino J, Gerbase MW, Wunderli W, et al. Respiratory viruses and severe lower respiratory tract complications in hospitalized patients. Chest. 2004;125(3):1033–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.3.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hohenadel IA, Kiworr M, Genitsariotis R, et al. Role of bronchoalveolar lavage in immunocompromised patients with pneumonia treated with a broad spectrum antibiotic and antifungal regimen. Thorax. 2001;56(2):115–20. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain P, Sandur S, Meli Y, et al. Role of flexible bronchoscopy in immunocompromised patients with lung infiltrates. Chest. 2004;125(2):712–22. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee BE, Robinson JL, Khurana V, et al. Enhanced identification of viral and atypical bacterial pathogens in lower respiratory tract samples with nucleic acid amplification tests. J Med Virol. 2006;78(5):702–10. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Elden LJ, van Kraaij MG, Nijhuis M, et al. Polymerase chain reaction is more sensitive than viral culture and antigen testing for the detection of respiratory viruses in adults with hematological cancer and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(2):177–83. doi: 10.1086/338238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Legoff J, Guerot E, Ndjoyi-Mbiguino A, et al. High prevalence of respiratory viral infections in patients hospitalized in an intensive care unit for acute respiratory infections as detected by nucleic acid-based assays. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(1):455–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.1.455-457.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garbino J, Gerbase MW, Wunderli W, et al. Lower respiratory viral illnesses: improved diagnosis by molecular methods and clinical impact. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(11):1197–203. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-781OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Storch GA. Respiratory Infections. In: Storch GA, editor. Essentials of Diagnostic Virology. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. pp. 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nolte FS, Marshall DJ, Rasberry C, et al. MultiCode-PLx system for multiplexed detection of seventeen respiratory viruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(9):2779–86. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00669-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall DJ, Reisdorf E, Harms G, et al. Evaluation of a multiplexed PCR assay for detection of respiratory viral pathogens in a public health laboratory setting. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(12):3875–82. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00838-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunsten S, Mikols CL, Grayson MH, et al. IL-12 p80-dependent macrophage recruitment primes the host for increased survival following a lethal respiratory viral infection. Immunology. 2009;126(4):500–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beigelman A, Gunsten S, Mikols CL, et al. Azithromycin Attenuates Airway Inflammation in a Noninfectious Mouse Model of Allergic Asthma. Chest. 2009 doi: 10.1378/chest.08-3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garbino J, Soccal PM, Aubert JD, et al. Respiratory viruses in bronchoalveolar lavage: a hospital-based cohort study in adults. Thorax. 2009;64(5):399–404. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.105155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wos M, Sanak M, Soja J, et al. The presence of rhinovirus in lower airways of patients with bronchial asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(10):1082–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-973OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayden FG. Rhinovirus and the lower respiratory tract. Rev Med Virol. 2004;14(1):17–31. doi: 10.1002/rmv.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neville LF, Mathiak G, Bagasra O. The immunobiology of interferon-gamma inducible protein 10 kD (IP-10): a novel, pleiotropic member of the C-X-C chemokine superfamily. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997;8(3):207–19. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(97)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonecchi R, Galliera E, Borroni EM, et al. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: an overview. Front Biosci. 2009;14:540–51. doi: 10.2741/3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charo IF, Ransohoff RM. The many roles of chemokines and chemokine receptors in inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):610–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spurrell JC, Wiehler S, Zaheer RS, et al. Human airway epithelial cells produce IP-10 (CXCL10) in vitro and in vivo upon rhinovirus infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289(1):L85–95. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00397.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNamara PS, Flanagan BF, Hart CA, et al. Production of chemokines in the lungs of infants with severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(8):1225–32. doi: 10.1086/428855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller AL, Bowlin TL, Lukacs NW. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced chemokine production: linking viral replication to chemokine production in vitro and in vivo. J Infect Dis. 2004;189(8):1419–30. doi: 10.1086/382958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wuest TR, Carr DJ. Dysregulation of CXCR3 signaling due to CXCL10 deficiency impairs the antiviral response to herpes simplex virus 1 infection. J Immunol. 2008;181(11):7985–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romero AI, Lagging M, Westin J, et al. Interferon (IFN)-gamma-inducible protein-10: association with histological results, viral kinetics, and outcome during treatment with pegylated IFN-alpha 2a and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(7):895–903. doi: 10.1086/507307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larrubia JR, Benito-Martinez S, Calvino M, et al. Role of chemokines and their receptors in viral persistence and liver damage during chronic hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(47):7149–59. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.7149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan MC, Cheung CY, Chui WH, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine responses induced by influenza A (H5N1) viruses in primary human alveolar and bronchial epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2005;6:135. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lagging M, Romero AI, Westin J, et al. IP-10 predicts viral response and therapeutic outcome in difficult-to-treat patients with HCV genotype 1 infection. Hepatology. 2006;44(6):1617–25. doi: 10.1002/hep.21407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wark PA, Bucchieri F, Johnston SL, et al. IFN-gamma-induced protein 10 is a novel biomarker of rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(3):586–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quint JK, Donaldson GC, Goldring JJ, et al. Serum IP-10 as a biomarker of human rhinovirus infection at exacerbation of COPD. Chest. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1541. Published online First: 16 October 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Zepeda EA, Rothenberg ME, Ownbey RT, et al. Human eotaxin is a specific chemoattractant for eosinophil cells and provides a new mechanism to explain tissue eosinophilia. Nat Med. 1996;2(4):449–56. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawaguchi M, Kokubu F, Kuga H, et al. Influenza virus A stimulates expression of eotaxin by nasal epithelial cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31(6):873–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papadopoulos NG, Papi A, Meyer J, et al. Rhinovirus infection up-regulates eotaxin and eotaxin-2 expression in bronchial epithelial cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31(7):1060–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.