Abstract

PURPOSE

The aim of this study was to compare the effects of a cardiac rehabilitation (CR) program tailored for women to a traditional program on perceptions of health among women with coronary heart disease.

METHODS

This 2-group randomized clinical trial compared the perceptions of health among 92 women completing a traditional 12-week CR program to 133 women completing a tailored program that included motivational interviewing guided by the Transtheoretical model of behavior change. Perceptions of health were measured using the SF-36 health survey at baseline, post-intervention, and at 6-month follow-up. ANOVA was used to compare changes in SF-36 subscale scores over time.

RESULTS

The group by time interaction was significant for the general health (F(2,446) = 3.80, P=.023), social functioning (F(2,446) = 4.85, P=.008), vitality (F(2,446) = 5.85, P=.003), and mental health (F(2,446) = 3.61, P=.028), subscales indicating that the pattern of change was different between the 2 groups. Of the 4 subscales on which there were significant group by time interactions, the tailored group demonstrated improved scores over time on all 4 while the traditional group improved on only the emotional role limitations and vitality subscales.

CONCLUSIONS

A tailored CR program improved general health perceptions, mental health, vitality, and social functioning in women when compared to traditional CR. To the extent that perceptions of health contribute to healthy behaviors fostered in CR programs, tailoring CR programs to alter perceptions of health may improve adherence.

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of death in American women.1 Multidisciplinary cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs of prescriptive exercise, health education, and psychological counseling are aimed at maximizing physical and psychosocial well-being.2–5 Despite international endorsement of CR as a model for secondary prevention4,6 and strong evidence of improved morbidity and mortality with participation,2–3,5 only about 15% to 20% of eligible women,7–10 compared to 22% to 30% of men,8,11–12 utilize these programs. Women particularly underrepresented in CR include the elderly, the obese, nonwhites, and those with greater co-morbidity, lower exercise capacity, less social support, lower education levels, competing family obligations, and incomplete medical insurance coverage.8,13–15 Women with CHD also report poorer perceptions of health than men both at entry and after completing secondary prevention programs,16 suggesting a possible programmatic gender issue that merits further investigation.

An important aspect of CR programs is the assessment of perceptions of health status at program entry to individualize patient treatment plans and after program completion to evaluate improvements gained from participation.4,17 The SF-36 health survey is frequently used to measure CR participant perceptions of health although the conceptual terms health-related quality of life, quality of life, and health perceptions are used interchangeably. Previous research has suggested that patient perceptions of health was modifiable and influenced the trajectory of their recovery and adherence to health behaviors including CR attendance.18–19 Improving patient perceptions of health, in addition to objective clinical health status, may foster long-term lifestyle behavior change and enhance their overall quality of life.20 Despite methodological limitations such as observational designs that include few women, CR appears to improve perceptions of health.13,21–25 Because CR is the standard of care for CHD patients, studies examining the effectiveness of these programs to a placebo control would be deemed unethical. The absence of a control group obscures extent of natural change in perceptions of health that may occur simply with the passage of time. McKee26 found significantly improved perceptions of health in a cohort of 187 CR patients (52 women) from baseline to program completion at 6 weeks with no further improvements by the 6 month follow-up. Yet, Grace et al27 found that women hospitalized for an acute cardiac event reported improved perceptions of health at 9 and 18 months after discharge regardless of whether or not they attended CR. Therefore, causal relationship between CR participation and improved perceptions of health is unclear and the question of clinical meaningful changes remains. Studies using experimental designs to compare efficacy of alternative CR models are generally less successful in showing group differences in perceptions of health.28–30

The current study was undertaken to address the underrepresentation of women in clinical trials,31 the higher mortality and morbidity of women with CHD compared to their male counterparts,32 the recognized unique psychosocial needs of women,9 and to improve their perceptions of health. Examining the effects of CR interventions designed for women is warranted given their generally poor perceptions of health and their unfavorable completion rates. The specific aim addressed here was to examine the effects of a tailored CR intervention compared to traditional CR for improving women's perceptions of their health. We hypothesized that women completing the tailored program would demonstrate greater improvements in perceptions of health compared with women completing traditional CR, and that these improvements would be sustain to a greater degree by the 6-month follow-up.

METHODS

This two-group randomized clinical trial examined physiological (eg, weight, lipid profile, cardiorespiratory fitness) and psychosocial outcomes (eg, anxiety, depression, social support) among women completing a traditional 12-week CR program to women completing a tailored program guided by the transtheoretical model (TTM) of behavior change delivered using motivational interviewing therapeutic methods. Details of the recruitment procedures, the interventions, and attendance are described elsewhere33–35 and summarized below. The Institutional Review Boards of the University of South Florida and the participating hospital approved the study protocol.

Participants, assessment, and randomization

We recruited participants, between January 2004 and March 2008, from those referred to an outpatient CR program in Florida. The inclusion criteria were women >21 years of age diagnosed with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI), angina, or having undergone coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within the last year; and able to read, write, and speak English. The exclusion criteria were health insurance coverage for less than 36 electrocardiogram-monitored exercise sessions, cognitive impairmentm or inability to ambulate. After receipt of the physician referral to CR, the study recruiter screened women for study eligibility and conducted individualized orientations for eligible women. The trained research assistant conducted the comprehensive evaluation and collected all baseline data in a private room in the CR facility after consent signing and before randomization. The statistician provided computer-generated random treatment allocation sequences that were placed in opaque envelopes that were sealed and delivered to the project director who opened the envelope to reveal the group assignment. A biased coin randomization algorithm36–37 was used to ensure balance between the interventions across time to accommodate a maximum of 8 electrocardiogram monitoring units per group. Outcome data were collected at 1 week and 6 months after completing CR by the same research assistant masked to group assignment.

Interventions

Traditional Intervention

The traditional CR program, nationally certified by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, was supervised by female nurses and exercise physiologists. The 12-week monitored exercise protocol involved aerobic exercise and resistance training 3 days per week. Exercise consisted of a 5-minute warm-up and 35–45 minutes of aerobic exercise with exercise heart rates maintained at 60–85% of maximal heart rate calculated from their baseline exercise tolerance test. Resistance training included wall-pulleys and hand weights followed by 5 minutes of cool-down exercises. Traditional group participants were free to choose any scheduled mixed-gender exercise session between 8 AM and 4 PM. Education classes on CHD risk factor modifications were provided by the CR personnel on 8 consecutive Mondays in the CR facility.

Tailored Intervention

The exercise protocol for this intervention was identical to that of the traditional CR program except for the exclusion of men. The multiple behavior change intervention, guided by the tenants of TTM38 and motivational interviewing39 was administered by female research nurses and exercise physiologists. At baseline and at 13 and 37 weeks women were assessed for their stage of motivational readiness to change healthy eating, physical activity, and stress management. The TTM computer-based expert system assessment,40 developed by Pro-Change Behavior Systems™ generated an individualized report tailored on TTM constructs. Participants received follow-up reports with feedback on TTM constructs being applied appropriately for each behavior and recommendations for stage-specific strategies to foster motivational stage progression. A clinical psychologist or a clinical nurse specialist, formally trained in motivational interviewing, conducted 60-minute individualized psychotherapeutic sessions at weeks 1, 6, and 12. The clinical nurse specialist and psychologist facilitated psychoeducational sessions on 10 consecutive Wednesdays.

Perceived Health Measures

The SF-36 Health Survey is the most widely used self-report measure of perceptions of health.41 The SF-36v2™ comprises 36 questions measuring perceptions of health on 8 subscales, 4 of which measure physical health (physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain and general health perceptions) and 4 that measure mental health (role limitations due to emotional problems, social functioning, vitality, and mental health). Subscale scores were summed and transformed to a 0–100 scale, with higher scores representing better perceptions of health. Internal consistency reliability estimates ranged from 0.78 to 0.93.

Baseline Physiological Measures

Blood pressure was measured with one automated oscillometric BP monitor (Datascope, Mahwah, NJ) according to established guidelines.43 Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). Body fat composition was determined using skinfold measurements taken at three sites (suprailium, triceps, and thigh) and percentage of body fat was calculated from standardized tables.44 Lipid profiles and serum glucose were measured after a 12-hour fast using the Cholestech LDX System. Using a modified Bruce protocol for the symptom limited exercise tolerance test, exercise capacity was expressed in units of metabolic equivalents.45

Attendance Measures

Exercise attendance, recorded at each session for hospital billing purposes, was calculated as the number of sessions attended out of a possible 36 prescribed sessions. Education attendance was expressed as a percentage of the number of sessions completed because the tailored intervention had 10 education sessions compared to 8 in the traditional program.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS, Version 17, for Windows (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Illinois). Descriptive baseline characteristics of the randomized groups were tabulated as means and standard deviations or as percentages. Primary analyses of perceptions of health are based on intent-to-treat principals. Analysis of variance was used to assess changes in perception of health scores among the 225 women with complete data at all 3 time-points. All tests were 2-tailed and evaluated for statistical significance using an alpha criterion of .05.

RESULTS

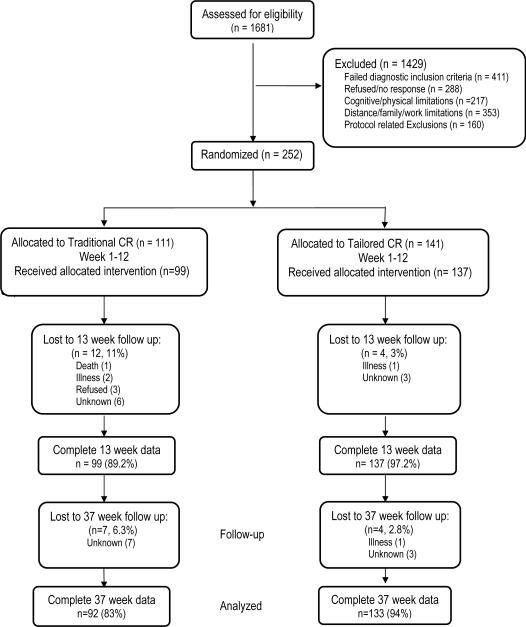

A total of 252 women were randomly allocated to either traditional CR or the tailored program with 225 women having complete SF-36 scores at all data-collection points. Figure 1 provides the flow of participants through each stage of the study. As shown in Table 1, baseline characteristics were not different by group. With a mean age of 63 years (SD=12, range, 31–87 years) most women were white (82%), married (53%), retired (47%), and a ≥high school education (92%). The inclusion criteria for CR included women who had undergone a PCI (50%) or CABG surgery (33.7%), treated medically for stable angina (11%), or sustaining an AMI (5%) within 3 months of CR enrollment. Baseline consumption of evidence-based medications did not differ between those in traditional CR compared to those in the tailored group. Participants were not different on measures of obesity, lipid profiles, or blood pressure (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow of Study Participants January 2004-March 2008 CR, cardiac rehabilitation

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Randomization Groupa

| Characteristic n (%) | Traditional CR n=92 | Tailored CR n=133 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD), y | 64±11 | 63±11 |

| Race or ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 56 (61) | 94 (71) |

| African American | 17 (18) | 20 (15) |

| Hispanic | 18 (20) | 18 (14) |

| Asian | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 38 (41) | 57 (43) |

| Some college | 40 (43) | 44 (33) |

| Baccalaureate degree | 8 (9) | 23 (17) |

| Graduate degree | 6 (7) | 9 (7) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 50 (54) | 73 (55) |

| Divorced/Separated | 20 (22) | 29 (22) |

| Widowed | 15 (16) | 26 (20) |

| Single never married | 7 (8) | 5 (4) |

| Work Status | ||

| Retired | 48 (52) | 66 (50) |

| Full-time/part-time | 28 (30) | 35 (26) |

| Disabled/unemployed | 16 (17) | 32 (24) |

| Diagnostic eligibility for cardiac rehabilitation | ||

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 39 (42) | 74 (56) |

| Coronary artery bypass graft surgery | 37 (40) | 39 (29) |

| Stable angina | 12 (13) | 13 (10) |

| Myocardial infarction | 4 (4) | 7 (5) |

CR, cardiac rehabilitation

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation; categorical variables are presented as number and (%).

Chi-square test and t test for discrete and continuous variables, respectively; P >.05 for all.

Table 2.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics by Randomization Groupa

| Characteristic | Traditional CR n = 92 | Tailored CR n = 133 |

|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 130 ± 17 | 125 ± 19 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 73 ± 11 | 71 ± 10 |

| Resting heart rate, bpm | 71 ± 10 | 71 ± 11 |

| Percent body fat | 37 ± 6 | 37 ± 6 |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 92 ± 32 | 90 ± 32 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 44 ± 14 | 46 ± 13 |

| Triglyceride level, mg/dL | 161 ± 79 | 146 ± 74 |

| Fasting glucose level, mg/dl | 106 ± 31 | 107 ± 37 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31 ± 7 | 31 ± 7 |

| Weight, lbs | 179 ± 41 | 180 ± 43 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 100 ± 15 | 100 ± 16 |

| Pack-years smoked | 16 ± 22 | 18 ± 25 |

| Peak exercise capacity, METS | 5 ± 2 | 6 ± 3 |

| Peak treadmill time, minutes | 8 ± 3 | 8 ± 4 |

| Medications, n (%) | ||

| Beta blockers | 77 (84) | 108 (81) |

| Statins | 83 (90) | 117 (88) |

| Aspirin | 81 (88) | 112 (84) |

| Clopidogrel | 53 (58) | 89 (67) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 27 (29) | 58 (44) |

| Antidepressant | 16 (17) | 31 (23) |

Abbreviations: CR, cardiac rehabilitation; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; METS, metabolic equivalents.

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation; categorical variables are number (%).

SF-36 Health Scores

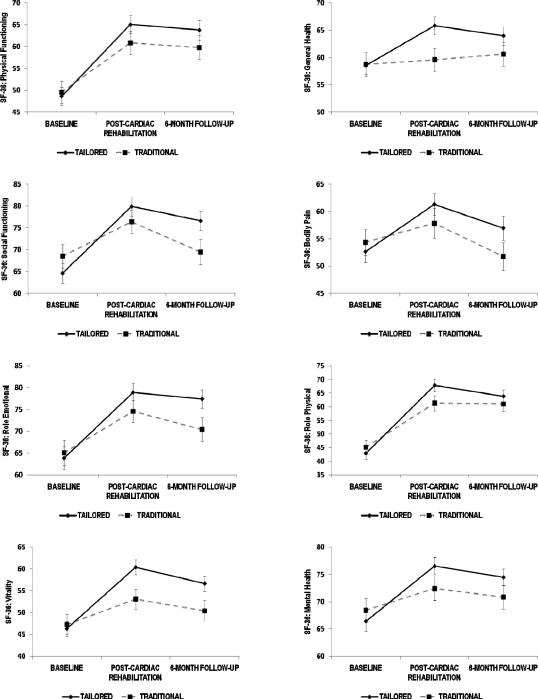

The SF-36 subscale profiles of the 2 groups are shown in Figure 2. Participants in both groups demonstrated improvement on all subscales by posttest with varying amount of decline by 6 months. Table 3 provides details of the data shown in Figure 2. The group by time interaction was significant for the general health, social functioning, vitality, and mental health subscales indicating that the pattern of change in scores over 3 time points differed significantly between the groups. The changes over time on the physical functioning, role limitations-physical, role limitations-emotional, and bodily pain subscales did not differ between the 2 groups. Of the 4 subscales on which there were significant group by time interactions, the tailored group demonstrated significantly improved scores over time on all four subscales while the traditional group improved on only the role limitations-emotional and vitality subscales.

Figure 2.

Group by Time Interaction Plots of 8 SF-36 Health Survey Subscale Mean Scores. Tests of interactions reveal significant effects for general health, social functioning, vitality, and mental health subscales only.

Table 3.

SF-36 Health Survey Scores by Intervention Group

| Variable | Traditional n=92 | Tailored n=133 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fa | (eta2) | Baseline | Post-CR | 6-month | Fb | (eta2) | Baseline | Post-CR | 6-month | Fc | (eta2) | |

| Physical Functioning | 2.11 | (.009) | 49.5±24.8 | 60.8±25.9 | 59.7±26.2 | 16.20e | (.068) | 48.6±24.1 | 65.0±24.8 | 63.7±25.5 | 50.51e | (.085) |

| Role Limitations-Physical | 2.66 | (.012) | 45.1±25.0 | 61.3±26.6 | 61.0±26.2 | 19.83e | (.082) | 42.8±23.6 | 67.8±26.5 | 63.8±26.8 | 60.00e | (.212) |

| Bodily Pain | 2.33 | (.010) | 54.3±22.6 | 57.8±26.1 | 51.7±24.4 | 2.82 | (.012) | 52.6±23.4 | 61.3±22.9 | 56.9±25.6 | 8.23e | (.036) |

| General Health | 3.80de | (.017) | 58.7±20.8 | 59.6±20.3 | 60.6±20.8 | <1 | (.002) | 58.5±18.9 | 65.8±18.8 | 64.0±19.5 | 12.84e | (.054) |

| Role Limitations-Emotional | 2.54 | (.011) | 65.0±27.6 | 74.5±24.5 | 70.4±25.9 | 5.61e | (.025) | 63.8±29.1 | 78.9±23.9 | 77.4±24.3 | 24.46e | (.099) |

| Social Functioning | 4.85e | (.011) | 68.5±25.9 | 76.4±25.3 | 69.4±27.9 | 4.76e | (.021) | 64.6±26.2 | 79.9±25.8 | 76.6±25.6 | 24.19e | (.098) |

| Vitality | 5.85de | (.026) | 47.2±21.8 | 53.0±22.0 | 50.3±23.4 | 4.18e | (.018) | 46.3±19.2 | 60.4±19.9 | 56.6±19.7 | 37.72e | (.145) |

| Mental Health | 3.61de | (.016) | 68.4±21.2 | 72.4±20.9 | 70.8±20.7 | 2.19 | (.010) | 66.4±20.9 | 76.5±18.0 | 74.4±17.9 | 22.03e | (.090) |

F test of group by time interaction (degrees of freedom (df) = 2, 446)

F test of simple main effect of time for traditional group (df = 2, 446)

F test of simple main effect of time for tailored group (df = 2, 446)

p<.05 adjusted for attendance

CR, cardiac rehabilitation

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

p<.05

We conducted detailed analyses to decompose the significant group by time interactions found for the mental health, vitality, general health and social functioning subscales. In all cases, the interaction from the baseline to the post-CR scores accounted for the overall interaction. While the 6-month follow-up scores were consistently higher in the tailored compared to the traditional group, the rates of decline on these scales from post-CR to the follow-up assessment were not different for the 2 groups. At the 6-month follow-up, the scores for both groups on these four scales remained above baseline levels.

Supplemental analyses to address the potential confounding influence of attendance on the subscale scores for which we found significant group by time interactions were conducted using analysis of covariance. Traditional group participants attended a mean of 30±10 of the 36 prescribed exercise sessions compared to 34±7.6 for the tailored group participants (F(1, 223) = 7.322, P=007). The mean percent attendance of the education sessions was also greater in the tailored group (89±21) than in the traditional group (62±30) (F(1, 223) = 63.843, P<001). Eleven percent (n=12) of the traditional group participants compared to 3% (n=4) of the tailored group failed to complete the post-CR assessment. Participants not completing the 6-month assessment included 2.8% (n=4) of the tailored compared to 6.3% (n=7) of traditional CR participants. Controlling for baseline scores and attendance, we found a significant group effect on the mental health (F(1,221) = 5.04, P=.026), the vitality (F(1,221) = 6.72, P=.010), and the general health subscales (F(1,221) = 5.92, P=.016) post-CR. The between group differences disappeared for the social functioning subscale when controlling for baseline scores and attendance (F(1,221) = 1.05, P=.307).

DISCUSSION

The study examined the effects of 2 different approaches to CR for women, a traditional contemporary program and a program tailored exclusively for women, on their perceptions of health. There were significant improvements on 4 dimensions of health, specifically, vitality, social functioning, mental health, and general health. Decomposition of the significant group by time interactions revealed that women in the tailored intervention exhibited more favorable improvements from baseline to post-CR than did women in the traditional group. Traditional CR was as successful as the tailored program at improving the scores on the physical functioning, role limitations-physical and role limitations-emotional subscales. The traditional program produced no change on the mental health, general health or bodily pain subscales. The tailored program produced significant improvements on all subscales. Furthermore, these improvements remained at the 6-month follow-up. The potential confounding effects of attendance on perceptions of health scores were also examined. Attendance accounted for some of these improvements. The tailored group effect remained significant for the mental health, vitality, and general health subscales but the effect on the social functioning subscale was attenuated when controlling for attendance.

While improved perceptions of health have been demonstrated in CR cohort studies, ours is the first experimental design to demonstrate the effects of different CR delivery models. This is also the first study to do so specifically for women. Women in the tailored program made greater gains (a change of at least 5 points or more) on all subscales than did women in traditional CR. Consensus on what constitutes a clinically important difference on the SF-36 has not been established. One expert panel defined a state change as the smallest amount that an individual score can shift by moving up or down 1 response choice on only 1 item on the scale while all other responses remain constant.46 Whether such differences are perceived as important to patients has not been determined.

Tingstrom et al28 examined health perceptions of 207 patients (54 women) randomized to either a problem-based learning CR or traditional CR and found no significant between group differences in improvements on any of the SF-36 subscales although both groups perceived better health at posttest. The Enhanced Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) trial evaluated the effects of a psychosocial intervention compared to traditional care for a subset of postmyocardial infarction patients (n=1,296; 557 women).29,47 While that intervention was ineffective in reducing risk of re-infarction or death, there were significantly greater improvements in the psychosocial group at 6 months on the mental health but not the physical health component of the SF-36.

In contrast to the current findings, Lie et al48 found no between group differences on the SF-36 for 185 CABG patients (19 women) randomized to either a home-based program or a control group 6 months post-surgery. However, both groups improved over time. Smith et al examined the rate of decline in perceptions of health of CABG patients (n=198, 36 women) 12 months after completion of a randomized trial comparing the effects of a home-based to a hospital-based CR.49 Participants in the home-based intervention demonstrated higher physical and mental health perception scores at baseline, at discharge after a 6-month CR program and 12 months after completing CR compared to the hospital-based group. One year after the intervention, there were no significant between-group differences. Observational designs without comparison conditions tend to produce effect sizes that are larger than in randomized trials. The improved perceptions of health typically observed in CR cohort studies with functionally debilitated patients at baseline might represent regression to the mean. The use of a comparison group would permit estimation of this type of artifact.

The current study demonstrates that tailoring CR for women can result in improvements in their perceptions of mental health, vitality, and general health to a greater degree than a traditional CR program. In comparison, Focht et al50 found that, compared to traditional CR, patients randomized to a group-based cognitive behavioral CR intervention significantly improved their scores only on the vitality subscale at 9 months post-CR. It is plausible that the gender-specific exercise, education and social interaction in the tailored program enhanced the perceptions of their health. Improved perceptions of health in women completing CR could potentially foster their informal endorsement of CR to other women who are ambivalent about attending CR.

Limitations

Caution is warranted when generalizing these results because participants were predominantly Caucasian women from a single institution in the southeastern United States. Second, it is not possible to know whether treatment effects observed would persist beyond 6 months. Finally, examining the efficacy of a bundled program such as ours is difficult; we cannot say which components had the greatest influence on perceptions of health. That the intervention used motivational interviewing, TTM tailoring, and gender-specific exercise, education, and social support may have synergistically led to improved perceptions of health.

Increasing the referral of eligible women to CR programs and raising awareness among physicians regarding the benefits of CR for women,51 could provide more women the opportunity to achieve optimum health following a cardiac event. Cardiac rehabilitation tailored for women has potential for improving their perceptions of health. Improving perceptions of health may positively influence CR adherence and foster healthy behaviors. Using the principles of comparative effectiveness research, such interventions need to be evaluated in more culturally diverse samples and in broader clinical contexts.52 A deeper understanding of the factors influencing patients' perceptions of health and how they are altered through CR and other interventions may provide clinicians with additional means to improve patient overall quality of life.

CONDENSED ABSTRACT

This randomized clinical trial found that compared to traditional cardiac rehabilitation (CR), women completing a motivationally-enhanced, gender-tailored CR program had significantly improved perceptions of health regarding their vitality, mental health, social functioning and general health. Improved perceptions of health may contribute to adherence to healthy behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study provided by the National Institute of Nursing Research (5R01 NR07678)

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2010 Update. A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;121:e1–e170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wenger NK. Current status of cardiac rehabilitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1619–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith SC, Jr., Allen J, Blair SN, et al. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update: endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2006;113:2363–2372. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balady GJ, Williams MA, Ades PA, et al. Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: 2007 update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee, the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Epidemiology and Prevention, and Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2007;27:121–129. doi: 10.1097/01.HCR.0000270696.01635.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suaya JA, Stason WB, Ades PA, Normand SL, Shepard DS. Cardiac rehabilitation and survival in older coronary patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piepoli MF, Corra U, Benzer W, et al. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: from knowledge to implementation. A position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Euro J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:1–17. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283313592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen JK, Scott LB, Stewart KJ, Young DR. Disparities in women's referral to and enrollment in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:747–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suaya JA, Shepard DS, Normand SL, Ades PA, Prottas J, Stason WB. Use of cardiac rehabilitation by Medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass surgery. Circulation. 2007;116:1653–1662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.701466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott LA, Ben-Or K, Allen JK. Why are women missing from outpatient cardiac rehabilitation programs? A review of multilevel factors affecting referral, enrollment, and completion. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2002;11:773–791. doi: 10.1089/15409990260430927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bethell H, Lewin R, Dalal H. Cardiac rehabilitation in the United Kingdom. Heart. 2009;95:271–275. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.134338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas RJ, King M, Lui K, et al. AACVPR/ACC/AHA 2007 performance measures on cardiac rehabilitation for referral to and delivery of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention services endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians, American College of Sports Medicine, American Physical Therapy Association, Canadian Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation, European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, Inter-American Heart Foundation, National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1400–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortes O, Arthur HM. Determinants of referral to cardiac rehabilitation programs in patients with coronary artery disease: a systematic review. Am Heart J. 2006;151:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanderson BK, Bittner V. Women in cardiac rehabilitation: outcomes and identifying risk for dropout. Am Heart J. 2005;150:1052–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casey E, Hughes JW, Waechter D, Josephson R, Rosneck J. Depression predicts failure to complete phase-II cardiac rehabilitation. J Behav Med. 2008;31:421–431. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanderson BK, Shewchuk RM, Bittner V. Cardiac rehabilitation and women: what keeps them away? J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2010;30:12–21. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181c85859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pischke CR, Weidner G, Elliott-Eller M, et al. Comparison of coronary risk factors and quality of life in coronary artery disease patients with versus without diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1267–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanderson BK, Southard D, Oldridge N. AACVPR consensus statement. Outcomes evaluation in cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: improving patient care and program effectiveness. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2004;24:68–79. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200403000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrie KJ, Cameron LD, Ellis CJ, Buick D, Weinman J. Changing illness perceptions after myocardial infarction: an early intervention randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:580–586. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broadbent E, Ellis CJ, Thomas J, Gamble G, Petrie KJ. Further development of an illness perception intervention for myocardial infarction patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau-Walker M. Importance of illness beliefs and self-efficacy for patients with coronary heart disease. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:187–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavie CJ, Milani RV. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training programs in patients > or = 75 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:675–677. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00393-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lavie CJ, Milani RV. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training on exercise capacity, coronary risk factors, behavioral characteristics, and quality of life in women. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:340–343. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80550-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jegier A, Szmigielska K, Bilinska M, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with coronary heart disease after residential vs ambulatory cardiac rehabilitation. Circ J. 2009;73:476–483. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavie CJ, Milani RV. Benefits of cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training in elderly women. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:664–666. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lavie CJ, Milani RV. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation, exercise training, and weight reduction on exercise capacity, coronary risk factors, behavioral characteristics, and quality of life in obese coronary patients. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:397–401. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89239-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKee G. Are there meaningful longitudinal changes in health related quality of life--SF36, in cardiac rehabilitation patients? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;8:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grace SL, Grewal K, Arthur HM, Abramson BL, Stewart DE. A prospective, controlled multisite study of psychosocial and behavioral change following women's cardiac rehabilitation participation. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:241–248. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tingstrom PR, Kamwendo K, Bergdahl B. Effects of a problem-based learning rehabilitation programme on quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;4:324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendes de Leon CF, Czajkowski SM, Freedland KE, et al. The effect of a psychosocial intervention and quality of life after acute myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) clinical trial. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2006;26:9–13. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carroll DL, Rankin SH. Comparing interventions in older unpartnered adults after myocardial infarction. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;5:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melloni C, Berger JS, Wang TY, et al. Representation of Women in Randomized Clinical Trials of Cardiovascular Disease Prevention. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:135–142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.868307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaccarino V. Ischemic Heart Disease in Women: Many Questions, Few Facts. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:111–115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.925313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beckie TM. A behavior change intervention for women in cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;21:146–153. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200603000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beckie TM, Mendonca MA, Fletcher GF, Schocken DD, Evans ME, Banks SM. Examining the challenges of recruiting women into a cardiac rehabilitation clinical trial. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2009;29:13–21. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31819276cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beckie TM, Beckstead JW. Predicting Cardiac Rehabilitation Attendance in a Gender-Tailored Randomized Clinical Trial. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2010;30:147–156. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181d0c2ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Efron B. Forcing a sequential experiment to be balanced. Biometrika. 1971;58:403–417. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofmeijer J, Anema PC, van der Tweel I. New algorithm for treatment allocation reduced selection bias and loss of power in small trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prochaska JO, Norcross JC, DiClemente CC. Changing for Good. HarperCollins; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Redding C, et al. Stage-based expert systems to guide a population of primary care patients to quit smoking, eat healthier, prevent skin cancer, and receive regular mammograms. Prev Med. 2005;41:406–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE. How to score version 2 of the SF-36 health survey. QualityMetric Incorporated; Lincoln, RI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 survey manual and interpretation guide. New England Medical Center, The Health Institute; Boston: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the subcommittee of professional and public education of the american heart association council on high blood pressure research. Circulation. 2005;111:697–716. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154900.76284.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jackson AS, Pollock ML, Ward A. Generalized equations for predicting body density of women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1980;12:175–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Bricker JT, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines) Circulation. 2002;106:1883–1892. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034670.06526.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wyrwich KW, Spertus JA, Kroenke K, Tierney WM, Babu AN, Wolinsky FD. Clinically important differences in health status for patients with heart disease: an expert consensus panel report. Am Heart J. 2004;147:615–622. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Froelicher ES, Miller NH, Buzaitis A, et al. The Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Trial (ENRICHD): strategies and techniques for enhancing retention of patients with acute myocardial infarction and depression or social isolation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003;23:269–280. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lie I, Arnesen H, Sandvik L, Hamilton G, Bunch EH. Health-related quality of life after coronary artery bypass grafting. The impact of a randomised controlled home-based intervention program. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9438-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith KM, Arthur HM, McKelvie RS, Kodis J. Differences in sustainability of exercise and health-related quality of life outcomes following home or hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11:313–319. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000136414.40017.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Focht BC, Brawley LR, Rejeski WJ, Ambrosius WT. Group-mediated activity counseling and traditional exercise therapy programs: effects on health-related quality of life among older adults in cardiac rehabilitation. Ann Behav Med. 2004;28:52–61. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2801_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scott LB, Allen JK. Providers' perceptions of factors affecting women's referral to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation programs: an exploratory study. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2004;24:387–391. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200411000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gibbons RJ, Gardner TJ, Anderson JL, et al. The American Heart Association's principles for comparative effectiveness research: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;119:2955–2962. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]