Abstract

Knockout of copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase (SOD1) and (or) cellular glutathione peroxidase (GPX1) has been reported to have dual impacts on coping with free radical-induced oxidative injury. Because bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS) triggers inflammatory responses involving the release of cytokines, nitric oxide and superoxide in targeted organs such as liver, in this study we used SOD1 knockout (SOD1-/-), GPX1 knockout (GPX1-/-), GPX1 and SOD1 double-knockout (DKO) and their wild-type (WT) mice to investigate the role of these two antioxidant enzymes in LPS-induced oxidative injury in liver. Mice of the four genotypes (2-month old) were killed at 0, 3, 6 or 12 h after an ip injection of saline or 5 mg LPS/kg body weight. The LPS injection caused similar increase in plasma alanine aminotransferase among the four genotypes. Hepatic total glutathione (GSH) was decreased (P < 0.05) compared with the initial values by the LPS injection at all time points in the WT mice, but only at 6 and 12 h in the other three genotypes. The GSH level in the DKO mice was higher (P < 0.05) than in the WT at 6 h. Although the LPS injection resulted in substantial increases in plasma NO in a time-dependent manner in all genotypes, the NO level in the DKO mice was lower (P < 0.05) at 3, 6, and 12 h than in the WT. The level in the GPX1-/- and SOD1-/- mice was also lower (P < 0.05) than in the WT at 3 h. The LPS-mediated hepatic protein nitration was detected in the WT and GPX1-/- mice at 3, 6 or 12 h, but not in the SOD1-/-. In conclusion, knockout of SOD1 and (or) GPX1 did not potentiate the LPS-induced liver injury, but delayed the induced hepatic GSH depletion and plasma NO production.

Keywords: Lipopolysaccharide, oxidative injury, glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase

Introduction

The Se-dependent glutathione peroxidase-1 (GPX1) and Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase (SOD1) are two major antioxidant enzymes in mammals. SOD1 converts superoxide anion to hydrogen peroxide, which is in turn degraded to water with the catalysis of GPX1. These two enzymes are both known to protect against oxidative stress, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) associated with acute paraquat and diquat toxicity, as well as ischemia reperfusion injury [1,2]. However, GPX1 and SOD1 may have different functions in coping with reactive nitrogen species such as peroxynitrite. Our laboratory has found that knockout of GPX1 had opposite impacts on diquat- and peroxynitrite-induced cell death in mouse primary hepatocytes [3]. Knockout of SOD1 was shown to attenuate acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity and hepatic protein nitration [4,5].

LPS, the glycolipid from the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, elicits inflammatory responses involving the release of various proinflammatory cytokines and contributes to systemic changes known as septic shock [6,7,8]. LPS is primarily cleared in the liver, and endotoxemia is frequently found in patients with liver failure [6]. It has been established that LPS induces the production of nitric oxide (NO), and subsequently the formation of peroxynitrite and protein nitration in various animals and cells [9,10,11,12]. Besides, LPS also induce the production of ROS in organs such as lung and liver [13,14]. ROS include oxygen free radicals such as superoxide anion, and non-radical but highly reactive molecules like hydrogen peroxide. Excessive generation of ROS results in the loss of balance between antioxidant system and prooxidants, and leads to the occurrence of oxidative injury in targeted organs.

Despite the free-radical generating nature of LPS and the alteration of GPX1 and SOD1 activities by LPS [15,16], the effect of knockout of GPX1 and (or) SOD1 on LPS-induced oxidative injury remains largely unknown. Previous reports were more focused on a pharmacological effect of natural additives [17,18]. In the present study, we used SOD1 knockout (SOD1-/-), GPX1 knockout (GPX1-/-), SOD1 and GPX1 double-knockout (DKO), and their wild-type (WT) mice to investigate the impact of knockout of these two enzymes on the LPS-induced hepatic oxidative injury in mice.

Materials and methods

Experimental mice

Our experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cornell University and conducted in accordance with the NIH guidelines for animal care. Wild type, GPX1-/-[19], and SOD1-/- [1] mice with the same genetic background (129/SVJ × C57BL/6), were initially provided by Dr. Y. S. Ho, Wayne State University (Detroit, MI) and were bred in our facility. Mice lacking both GPX1 and SOD1 (DKO) were generated in our laboratory by crossing the individual knockouts. Genotypes were confirmed by PCR and enzyme activity assays. Mice were fed a diet containing adequate levels of all required nutrients, given free access to feed and distilled water, and housed in shoebox cages in a constant (22 °C) animal room with a 12-h light:dark cycle.

LPS Treatment and sample collection

LPS was prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Four genotypes of mice (8-10 weeks old) were injected (i.p.) with LPS at 5 mg/kg body weight following an overnight (8 h) fast. The mice were euthanized for blood and liver sample collection at 3, 6 or 12 h post the injection. PBS injected mice were killed immediately after injection and were served as the control. All samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C before proceeding for analyses.

Biochemical analyses

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise indicated. Plasma ALT activity was determined spectrophotometrically following the method outlined by Sigma. Total glutathione concentration was determined by the glutathione recycling assay and was expressed as nmol/mg protein [20]. Cellular GPX1 activity was measured using the coupled assay of reduced NADPH oxidation using H2O2 as a substrate [20]. The enzyme activity was expressed as nmol of glutathione oxidized per minute per mg of protein. Total SOD activity was determined using a water-soluble formazan dye kit (Dojindo Molecular Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Plasma nitrate and nitrite was determined as previously described to monitor LPS-induced NO production [5,21].

Western blot

Liver samples were homogenized in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.8, containing 0.1% Triton X-100, 1.34 mM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid, 1 mM PMSF, 10 g peptstain A/ml, 10 g leupeptin/ml, and 10 g aprotinin/ml. The homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. Protein concentration was determined as described by Lowry et al. [22]. The supernatant (100 μg protein per lane) was loaded onto SDS-PAGE (12% gel), transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, which was blocked with 5% milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with mouse anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), followed by a secondary HRP-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for 1 hr at room temperature. Blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL)

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the GLM procedure in SAS (release 6.11, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) as a one-way ANOVA with time repeated measurements. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Effect of LPS on hepatic GPX1 and SOD activity

As expected, little hepatic GPX1 activity was detected in the GPX1-/- and DKO mice, and little total SOD activity was detected in the SOD1-/- and DKO mice. LPS treatment did not result in significant changes of GPX1 activity in the WT mice, although a slight decrease was found at 6 h. Baseline hepatic GPX1 activity was around 35% lower (P < 0.05) in the SOD1-/- mice compared with the WT. LPS administration led to the reduction of GPX1 activity by 16.5% (P < 0.05) at 12 h compared with the initial activity at 0 h in the liver of SOD1-/- mice (Table 1). Total SOD activity in the WT mice was 11.5% (P < 0.05) lower at 6 h than the initial activity (0 h). No significant decrease was detected at 9 h and 12 h in the WT. Over the course of treatment, LPS administration did not lead to significant changes of total SOD activity in the GPX1-/- mice (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effect of LPS on hepatic GPX1 and total SOD activity in different genotypesa

| Time post-injection | 0 h | 3 h | 6 h | 12 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular glutathione peroxidase (GPX1) nmol of glutathione oxidized per min per mg of protein | ||||

| WT | 752±20 | 705±28 | 736±19 | 751±10 |

| GPX1-/- | 7.4±0.8† | 8.5±0.5† | 8.1±0.2† | 8.9±0.5† |

| SOD1-/- | 486±31† | 483±41† | 452±17† | 406±4.2†* |

| DKO | 7.6±0.5† | 8.1±0.5† | 9.4±0.5† | 8.5±0.5† |

| Total superoxide dismutase (SOD) 50% formazan dye formation rate inhibition per mg of protein | ||||

| WT | 1405±10 | 1243±12* | 1361±73 | 1341±7.5 |

| GPX1-/- | 1280±42 | 1249±36 | 1261±7.6 | 1306±46 |

| SOD1-/- | 13±0.8† | 16±3.1† | 14±3.3† | 16±1.1† |

| DKO | 7.5±0.8† | 13±2.4† | 9.6±1.2† | 9.3±0.4† |

Mice were treated with 5 mg LPS / kg body weight for 0, 3, 6 or 12 h.

P < 0.05 vs. 0 h within genotypes

P ± 0.05 vs. WT within the same time. Values are means ± S.E. (n = 3-4). The LPS treatment caused GPX1 activity decrease in the SOD1-/- mice at 12 h, and caused SOD activity decrease in the WT mice at 6h.

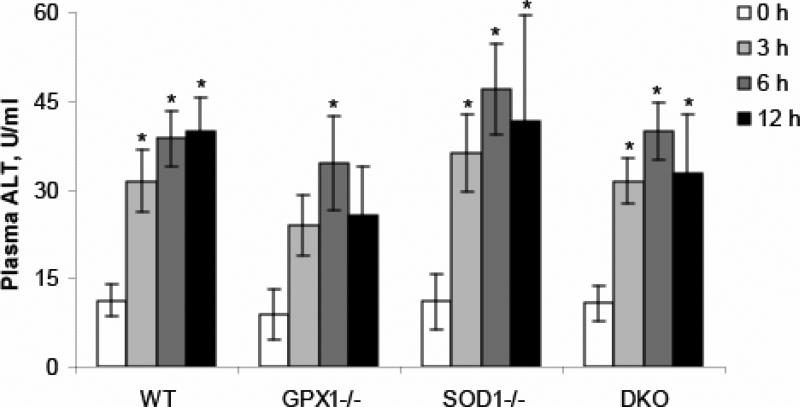

LPS resulted in similar liver injury in all genotypes

Plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity was elevated (P < 0.05) in all genotypes after LPS administration (Fig. 1). The fold of increase was 1.8, 2.5 and 2.6 times (P < 0.05), respectively, at 3, 6 and 9 h in the WT mice. The fold of increase in GPX1-/- mice was 1.7, 2.9 (P < 0.05) and 2.0 times, respectively. In the SOD1-/- mice, LPS exposure led to plasma ALT increase by 2.3, 3.3 and 3.8 times (P < 0.05), respectively, at 3, 6, and 9 h, while the LPS-induced increase of ALT activity in the DKO was 1.9, 2.7 and 2.1 times (P < 0.05), respectively. No significant difference of plasma ALT activities was detected between genotypes within the same time point (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of GPX1 or SOD1 knockout on the LPS-induced changes in plasma ALT activities. Values are means ± S.E. (n=5-8). * P < 0.05 vs. 0 h within genotypes.

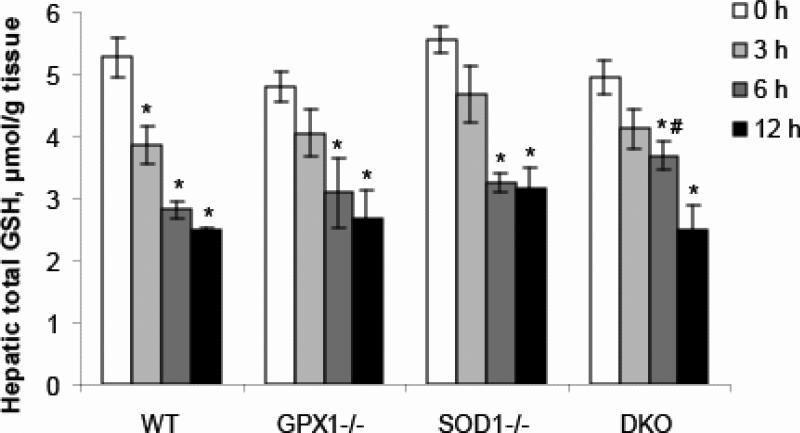

LPS caused reduction of hepatic glutathione (GSH) in all genotypes

LPS treatment led to decrease (P < 0.05) of hepatic total GSH in all genotypes (Fig. 2). In the WT mice, total GSH level was decreased by 27.1, 46.7 and 53.1% (P < 0.05), respectively, at 3, 6, and 9 h post LPS treatment. Total GSH level was reduced by 15.7, 35.7 (P < 0.05) and 44.3% (P < 0.05) in the GPX1-/- mice, 15.9, 41.5 (P < 0.05) and 43.0% (P < 0.05) in the SOD1-/- mice, and 16.8, 25.7 and 49.4% (P < 0.05) in the DKO mice, respectively, at 3, 6, and 9 h. Total GSH level at 6 h was higher (P < 0.05) in the DKO mice than in the WT. No significant difference of initial GSH levels was detected between genotypes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of GPX1 or SOD1 knockout on the LPS-induced changes in hepatic GSH concentrations. Values are means ± S.E. (n=3-4). * P < 0.05 vs. 0 h within genotypes; # P < 0.05 vs. WT within the same time.

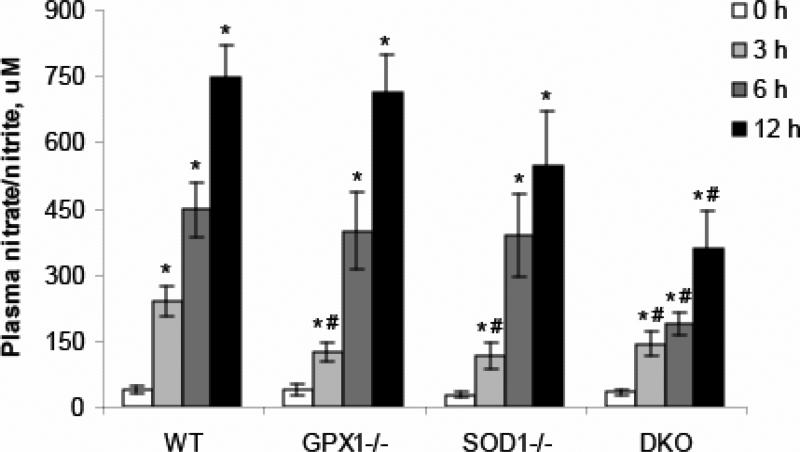

Effect of GPX1 and (or) SOD1 knockout on LPS- induced NO production

Plasma nitrite/nitrate was measured as an indicator of NO production. LPS treatment induced substantial increase in NO production in the WT mice, and the fold of increase was 5.5, 11.1 and 19.3 times (P < 0.05), respectively, at 3, 6 and 9 h (Fig. 3). LPS also induced significant increase of NO level in other three genotypes. The NO level was increased by 2.3, 9.5 and 17.8 times (P < 0.05) in the GPX1-/- mice, by 3.2, 13.0 and 18.7 times (P < 0.05) in the SOD1-/- mice, and by 3.2, 4.6 and 9.6 times (P < 0.05) in the DKO mice, respectively, at 3, 6 and 9 h post LPS treatment. Compared with the WT mice, the NO level at 3 h was significantly lower (P < 0.05) in the GPX1-/- and SOD1-/- mice. LPS administration resulted in lower (P < 0.05) NO production in the DKO mice than in the WT at all three time points 3, 6 and 9 h (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of GPX1 or SOD1 knockout on the LPS-induced plasma nitric oxide production. Values are means ± S.E. (n=5-8). * P < 0.05 vs. 0 h within genotypes; # P < 0.05 vs. WT within the same time.

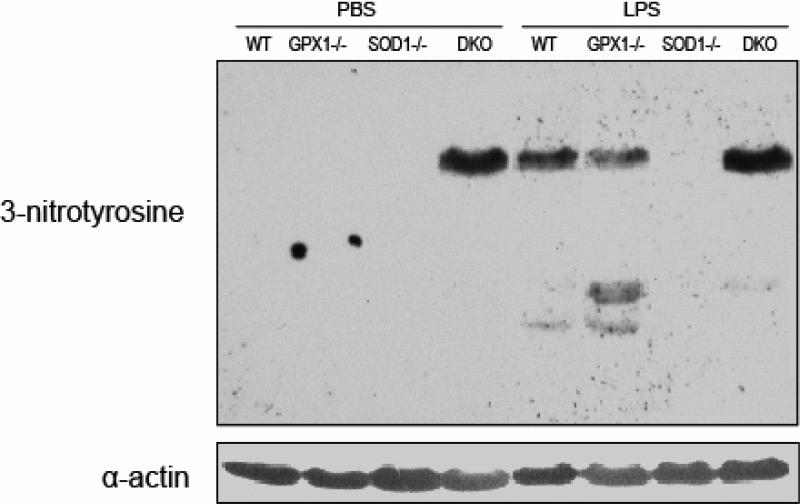

Effect of GPX1 and (or) SOD1 knockout on LPS- induced protein nitration

Protein nitration was assessed 6 h post LPS treatment. LPS induced the formation of protein nitrotyrosine in the liver of WT and GPX1-/- mice, but not in the SOD1-/- (Fig. 4). No background hepatic protein nitration was detected in the WT, GPX1-/- and SOD1-/- genotypes treated with PBS. However, there was a nitration band detected in the liver of PBS-treated DKO mice. The LPS treatment did not cause apparent additional hepatic protein nitration in the DKO mice (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A representative blot (n=3) shows the effect of knockout of GPX1 and/or SOD1 on the LPS-induced protein nitration at 6 h.

Discussion

There are a number of reports on role of free radicals in liver oxidative injury during endotoxemia. A few antioxidants including vitamin C and melatonin have been demonstrated to protect animals from LPS intoxication [23,24,25,26]. Unexpectedly, in the present study knockout of SOD1 and (or) GPX1 did not potentiate LPS-induced liver injury. Although being generally considered as antioxidant enzymes, SOD1 and GPX1 have been shown to have multiple functions in succession. Besides superoxide dismutase activity, SOD1 also possesses peroxidase activity, which cause generation of free radicals such as hydroxyl radical [27,28]. SOD1 has also been shown to catalyze the formation of protein nitrotyrosine from peroxynitrite [5,29]. Consequently, deleterious roles of SOD1 have been reported in some studies [30,31]. Constitutive overexpression of SOD1 promoted kainic acid-induced apoptosis of neurons, which was probably associated with free radical generating activity of this enzyme [32]. Knockout of SOD1 increased the resistance to APAP-induced hepatotoxicity, and the inhibition of SOD1-mediated protein nitration was suggested part of the protective mechanisms [4,5]. Compared with SOD1, there are fewer reports regarding the adverse role of GPX1. However, mice overexpressing GPX1 showed a decreased resistance to APAP hepatotoxicity [33]. On the other hand, knockout of GPX1 resulted in higher resistance to kainic acid-induced mortality and epileptic seizure in mouse brain [34]. These studies indicate that the previously reported protection from antioxidant molecules is more likely a pharmacological effect on LPS-induced liver injury. The physiological function of SOD1 and GPX1 seems more complicated and intoxication context dependent.

Numerous studies have been shown the activity regulation of antioxidant enzymes during endotoxemia. Despite the reported conflicted outcomes [16,35], more evidence has been in support of the notion of down-regulated GPX1 and SOD activity after LPS administration [17,36,37]. Indeed, LPS led to decrease of SOD and GPX1 activities, particularly at 6 h. As reported earlier [1,38], mice deficient in SOD1 exhibited lower baseline GPX1 activity. Knockout of SOD1 resulted in a delayed but larger decrease in GPX1 activity during endotoxemia compared with the wild-type. The presence of SOD1 in the wild-type mice likely helps the relief of oxidative stress from LPS administration, and sequentially protects GPX1 from the loss of enzymatic activity. Knockout of SOD1 might further increase the vulnerability of GPX1 to oxidative modification, as evidenced by the larger GPX1 activity reduction in the SOD1-/- mice. Interestingly, no such change of SOD activity was detected in the GPX1-/- mice, indicating differential impact of knockout of GPX1 on in vivo oxidative defense.

As a major intracellular antioxidant against varieties of intoxications, balance of GSH level is critical to maintain redox control of cellular biological functions, including the thiol moieties of proteins and the reduced form of biologically active molecules [39]. During endotoxemia, liver serves as the main source of plasma GSH and exhibited enhanced sinusoidal glutathione efflux [36,40]. The present study confirms the findings of previous reports which showed that LPS led to down-regulation of hepatic GSH [40,41]. It has been suggested the increased NO synthesis led to a decrease of hepatic GSH levels during endotoxemia, primarily through the inhibition of -glutamylcysteine ligase activity and expression [36,41]. Indeed, GSH levels in the WT mice exhibited a significant decrease at 3 h when higher NO was produced at this time point compared with the other three genotypes. Along with the less NO generation at 6 h, GSH level in the DKO mice was apparently higher at this time point. However, the NO level at 12 h might have surpassed the threshold in the DKO mice, leading to a substantial drop in GSH concentration. Our findings provided further evidence in support of the counteraction of NO and GSH during endotoxemia.

Compared with the WT, the DKO mice exhibited lower NO production during LPS intoxication. Although the underlying mechanism remains to be explored, the induced liver injury was similar between these two genotypes. Indeed, Sakaguchi et al. [42] suggested NO was not crucial for liver injury during endotoxemia. They reported administration of nitric oxide inhibitors did not affect lipid peroxide formation in liver caused by LPS challenge. Similarly, the formation of protein nitration was also not in line with the LPS-induced liver injury. Protein nitration, resulted from the reaction between peroxynitrite and protein tyrosine residues, is considered an event which alters or damages normal protein function. The absence of hepatic protein nitration in the SOD1-/- mice was consistent with our previous finding where SOD1 catalyzes the formation of protein nitration in murine liver [5]. Although we were unable to demonstrate how the nitration band appeared in control DKO mice, it is likely that double-knockout of SOD1 and GPX1 leads this specific protein to a higher susceptibility of spontaneous tyrosine modification.

In conclusion, knockout of SOD1 and (or) GPX1 did not potentiate the LPS-induced liver injury, but delayed the induced hepatic GSH depletion and plasma NO production. The generation of NO and protein nitration was not critical to LPS-induced liver injury. This study also provided alternative view of functions of antioxidant enzymes during endotoxemia.

-

◆

Knockout of antioxidant enzymes SOD1 or GPX1 did not potentiate the LPS-induced hepatic oxidative injury.

-

◆

Nitric oxide production and protein nitration were not critical to LPS-induced liver injury.

-

◆

The present study provided further evidence in support of the counteraction between nitric oxide and glutathione during endotoxemia.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health grant DK53108 to XGL.

Abbreviations

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- SOD1

copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase

- GPX1

cellular glutathione peroxidase 1

- DKO

double-knockout of SOD1 and GPX1

- WT

wild-type

- NO

nitric oxide

- GSH

glutathione

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ho YS, Gargano M, Cao J, Bronson RT, Heimler I, Hutz RJ. Reduced fertility in female mice lacking copper-zinc superoxide dismutase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:7765–7769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshida T, Maulik N, Engelman RM, Ho Y-S, Das DK. Targeted disruption of the mouse Sod1 gene makes the hearts vulnerable to ischemic reperfusion injury. Circ. Res. 2000;86:264–269. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu Y, Sies H, Lei XG. Opposite roles of selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase-1 in superoxide generator diquat- and peroxynitrite-induced apoptosis and signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43004–43009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106946200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lei XG, Zhu JH, McClung JP, Aregullin M, Roneker CA. Mice deficient in Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase are resistant to acetaminophen toxicity. Biochem. J. 2006;399:455–461. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu JH, Zhang X, Roneker CA, McClung JP, Zhang S, Thannhauser TW, Ripoll DR, Sun Q, Lei XG. Role of copper,zinc-superoxide dismutase in catalyzing nitrotyrosine formation in murine liver. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45:611–618. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su GL. Lipopolysaccharides in liver injury: molecular mechanisms of Kupffer cell activation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G256–G265. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00550.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayeux PR. Pathobiology of lipopolysaccharide. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. 1997;51:415–435. doi: 10.1080/00984109708984034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luster MI, Germolec DR, Yoshida T, Kayama F, Thompson M. Endotoxin-induced cytokine gene expression and excretion in the liver. Hepatology. 1994;19:480–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorg B, Wettstein M, Metzger S, Schliess F, Haussinger D. Lipopolysaccharide-induced tyrosine nitration and inactivation of hepatic glutamine synthetase in the rat. Hepatology. 2005;41:1065–1073. doi: 10.1002/hep.20662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elsasser TH, Kahl S, MacLeod C, Nicholson B, Sartin JL, Li C. Mechanisms underlying growth hormone effects in augmenting nitric oxide production and protein tyrosine nitration during endotoxin challenge. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3413–3423. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Y, Wang X, Cederbaum AI. Lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in rats treated with the CYP2E1 inducer pyrazole. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G308–G319. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00054.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fries DM, Paxinou E, Themistocleous M, Swanberg E, Griendling KK, Salvemini D, Slot JW, Heijnen HF, Hazen SL, Ischiropoulos H. Expression of inducible nitric-oxide synthase and intracellular protein tyrosine nitration in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:22901–22907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210806200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang C, Walker LM, Hinson JA, Mayeux PR. Oxidant stress in rat liver after lipopolysaccharide administration: effect of inducible nitric-oxide synthase inhibition. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;293:968–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bautista AP, Spitzer JJ. Superoxide anion generation by in situ perfused rat liver: effect of in vivo endotoxin. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;259:G907–G912. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.6.G907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iqbal M, Cohen RI, Marzouk K, Liu SF. Time course of nitric oxide, peroxynitrite, and antioxidants in the endotoxemic heart. Crit. Care Med. 2002;30:1291–1296. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200206000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ben-Shaul V, Sofer Y, Bergman M, Zurovsky Y, Grossman S. Lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative stress in the liver: comparison between rat and rabbit. Shock. 1999;12:288–293. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu DZ, Chiang PJ, Chien SP, Huang BM, Liu MY. Parenteral sesame oil attenuates oxidative stress after endotoxin intoxication in rats. Toxicology. 2004;196:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur G, Tirkey N, Chopra K. Beneficial effect of hesperidin on lipopolysaccharide-induced hepatotoxicity. Toxicology. 2006;226:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho YS, Magnenat JL, Bronson RT, Cao J, Gargano M, Sugawara M, Funk CD. Mice deficient in cellular glutathione peroxidase develop normally and show no increased sensitivity to hyperoxia. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:16644–16651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu JH, Lei XG. Double null of selenium-glutathione peroxidase-1 and copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase enhances resistance of mouse primary hepatocytes to acetaminophen toxicity. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2006;231:545–552. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollock JS, Forstermann U, Mitchell JA, Warner TD, Schmidt HH, Nakane M, Murad F. Purification and characterization of particulate endothelium-derived relaxing factor synthase from cultured and native bovine aortic endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:10480–10484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sewerynek E, Melchiorri D, Reiter RJ, Ortiz GG, Lewinski A. Lipopolysaccharide-induced hepatotoxicity is inhibited by the antioxidant melatonin. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;293:327–334. doi: 10.1016/0926-6917(95)90052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cadenas S, Rojas C, Barja G. Endotoxin increases oxidative injury to proteins in guinea pig liver: protection by dietary vitamin C. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1998;82:11–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1998.tb01391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uedono Y, Takeyama N, Yamagami K, Tanaka T. Lipopolysaccharide-mediated hepatic glutathione depletion and progressive mitochondrial damage in mice: protective effect of glutathione monoethyl ester. J. Surg. Res. 1997;70:49–54. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cadenas S, Cadenas AM. Fighting the stranger-antioxidant protection against endotoxin toxicity. Toxicology. 2002;180:45–63. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodgson EK, Fridovich I. The interaction of bovine erythrocyte superoxide dismutase with hydrogen peroxide: chemiluminescence and peroxidation. Biochemistry. 1975;14:5299–5303. doi: 10.1021/bi00695a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goss SP, Singh RJ, Kalyanaraman B. Bicarbonate enhances the peroxidase activity of Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase. Role of carbonate anion radical. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:28233–28239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ischiropoulos H, Zhu L, Chen J, Tsai M, Martin JC, Smith CD, Beckman JS. Peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration catalyzed by superoxide dismutase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992;298:431–437. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90431-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groner Y, Elroy-Stein O, Avraham KB, Schickler M, Knobler H, Minc-Golomb D, Bar-Peled O, Yarom R, Rotshenker S. Cell damage by excess CuZnSOD and Down's syndrome. Biomed. Pharmacother. 1994;48:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0753-3322(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott MD, Meshnick SR, Eaton JW. Superoxide dismutase amplifies organismal sensitivity to ionizing radiation. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:2498–2501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bar-Peled O, Korkotian E, Segal M, Groner Y. Constitutive overexpression of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase exacerbates kainic acid-induced apoptosis of transgenic Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:8530–8535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mirochnitchenko O, Weisbrot-Lefkowitz M, Reuhl K, Chen L, Yang C, Inouye M. Acetaminophen toxicity. Opposite effects of two forms of glutathione peroxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:10349–10355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang D, Akopian G, Ho Y-S, Walsh JP, Andersen JK. Chronic brain oxidation in a glutathione peroxidase knockout mouse model results in increased resistance to induced epileptic seizures. Exp. Neurol. 2000;164:257–268. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watson AM, Warren G, Howard G, Shedlofsky SI, Blouin RA. Activities of conjugating and antioxidant enzymes following endotoxin exposure. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 1999;13:63–69. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0461(1999)13:2<63::aid-jbt1>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Payabvash S, Ghahremani MH, Goliaei A, Mandegary A, Shafaroodi H, Amanlou M, Dehpour AR. Nitric oxide modulates glutathione synthesis during endotoxemia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;41:1817–1828. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balkan J, Parldar FH, Dogru-Abbasoglu S, Aykac-Toker G, Uysal M. The effect of taurine or betaine pretreatment on hepatotoxicity and prooxidant status induced by lipopolysaccharide treatment in the liver of rats. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005;17:917–921. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu JH, McClung JP, Zhang X, Aregullin M, Chen C, Gonzalez FJ, Kim TW, Lei XG. Comparative impacts of knockouts of two antioxidant enzymes on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2009;234:1477–1483. doi: 10.3181/0904-RM-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meister A. Glutathione, ascorbate, and cellular protection. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1969s–1975s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaeschke H. Enhanced sinusoidal glutathione efflux during endotoxin-induced oxidant stress in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:G60–G68. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.1.G60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minamiyama Y, Takemura S, Koyama K, Yu H, Miyamoto M, Inoue M. Dynamic aspects of glutathione and nitric oxide metabolism in endotoxemic rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:G575–G581. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.4.G575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakaguchi S, Furusawa S, Yokota K, Sasaki K, Takayanagi M, Takayanagi Y. Effect of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors on lipid peroxide formation in liver caused by endotoxin challenge. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2000;86:162–168. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2000.d01-30.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]