Abstract

The mammalian embryo represents a fundamental paradox in biology. Its location within the uterus, especially early during development when embryonic cardiovascular development and placental blood flow are not well-established, leads to an obligate hypoxic environment. Despite this hypoxia, the embryonic cells are able to undergo remarkable growth, morphogenesis, and differentiation. Recent evidence suggests that embryonic organ differentiation, including pancreatic β-cells, is tightly regulated by oxygen levels. Since a major determinant of oxygen tension in mammalian embryos after implantation is embryonic blood flow, here we used a novel survivable in utero intracardiac injection technique to deliver a vascular tracer to living mouse embryos. Once injected, the embryonic heart could be visualized to continue contracting normally, thereby distributing the tracer specifically to only those regions where embryonic blood was flowing. We found that the embryonic pancreas early in development shows a remarkable paucity of blood flow, and that the presence of blood flow correlates with the differentiation state of the developing pancreatic epithelial cells in the region of the blood flow.

INTRODUCTION

The embryonic mouse pancreas originates as two evaginations from the foregut. The early formation of the pancreas is thought to be under the control of multiple extracellular factors (Gittes, 2009). Commitment of endoderm to a pancreatic fate is thought to be controlled by notochord-derived FGF2 and activins (Hebrok et al., 1998). As development progresses, however, the paired dorsal aortae fuse in the midline, interposing themselves between the notochord and the dorsal pancreas. Interestingly, the aortic endothelial cells foster pdx1 and ptf1a expression (Lammert et al., 2001; Yoshitomi and Zaret, 2004), with subsequent insulin expression in the endoderm. These early embryonic recombination experiments of aortic endothelium and foregut were performed in vitro, without blood flow, suggesting that blood flow may be unnecessary for the endothelium-induced pancreatic differentiation. However, these in vitro experiments were performed in the presence of 21% oxygen and fully supplemented medium (serum, etc.), so a key in vivo constituent of blood flow might have been replaced by the culture conditions. Recent studies in vitro demonstrate that 21% oxygen (which may be a 4–6-fold higher oxygen tension than exists in the perfused regions of the embryo) may have supra-physiologic effects on pancreatic differentiation, and in particular enhanced endocrine differentiation (Fraker et al., 2007; Heinis et al., 2010).

Tissue oxygen tension in the early mammalian embryo represents a fascinating biological conundrum. The early mammalian embryo is located within the uterus, with a non-existant or immature cardiovascular system and blood supply. Despite this hypoxic enviroment, the embryo is still able to undergo rapid growth and organogenesis. It seems plausible that the inflow of blood, with the resulting increased oxygen tension, may be a control point for differentiation. Like the pancreas, many other developing tissues have been shown to use oxygen as a control point for differentiation (Fraker et al., 2007; Heinis et al., 2010). Thus, endothelial cells alone may not actually be sufficient to induce organ development in utero, but may be dependent on additional signals from blood flow and oxygen. Such a specific dependence of organ development on blood flow rather than just endothelial cells has been shown for the developing zebrafish kidney (Serluca et al., 2002).

In the developing pancreas, we and others have shown that there are abundant PECAM-positive and VEGFR2-positive endothelial cells throughout the early embryonic mesenchyme (Lammert et al., 2001). Despite these numerous endothelial cells, however, the early epithelium does not undergo diffuse differentiation, but rather shows a controlled, staged pattern of differentiation. In particular, between E9.5 and E13.5 there is mainly growth and branching of pdx1-positive pancreatic epithelium, with relatively little exocrine and endocrine differentiation (especially insulin-positive differentiation) (Gittes, 2009). Then, after 13.5 a transition occurs wherein there is a rapid expansion of acinar cells and insulin-positive beta cells (Rall et al., 1973).

Here, we developed a new technique of ultrasound backscatter microscopy-guided in utero intracardiac injection in early mouse embryos. Using the injection of vascular tracers, we are able to determine where the living embryonic mouse heart is pumping blood. We now present correlative evidence that enhanced blood flow and oxygenation in the developing mouse pancreas may underlie the normal changes in differentiation kinetics seen during mouse embryonic pancreatic development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Mice were maintained according to the Animal Research and Care Committee at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, and the University of Pittsburgh IACUC.

Tissue Preparation

For immunolabeling on cryopreserved sections, tissues were fixed, sectioned and stained as previously described (Esni et al., 1999).

Immunolabeling

The following antibodies were used at the indicated dilutions for immunofluorescence analysis: guinea pig anti-insulin 1:1000 (Linco); guinea pig anti-glucagon 1:1000 (Linco); rabbit anti-glucagon 1:1000 (Linco); goat anti-amylase 1:500 (Santa Cruz); rat anti-E-Cadherin 1:200 (Zymed); rat anti-PECAM 1:50 (BD Pharmigen); goat anti-Pdx1 1:10000;(AbCam); mouse anti-NGN3 1:2000 (Hybridoma Bank), chicken anti-β-galactosidase 1:1000 (Abcam), goat anti-vimentin 1:50 (Santa Cruz). The following reagents were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories: Biotin-conjugated anti-rabbit 1:500, anti-rat 1:500 anti-goat 1:250; Cy2- and Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-guinea pig 1:300, donkey anti-rabbit 1:300; donkey anti-rat 1:300, donkey anti-mouse 1:300; Cy2-conjugated streptavidin 1:300, Cy3-conjugated streptavidin, 1:1000; and Cy5-conjugated streptavidin 1:100. Images were collected on a Zeiss Imager Z1 microscope with a Zeiss AxioCam driven by Zeiss AxioVision Rel.4.7 software.

Whole-Mount immunohistochemistry

Tissue preparation and whole-mount immunohistochemistry on embryonic pancreas was performed as previously described (Esni et al., 2001).

Culture of pancreatic rudiments

Isolation and culture of E11.5 foregut containing pancreatic rudiments were carried out as previously described (Esni et al., 2001; Esni et al., 2005), with BrdU added for the last 2 days of culture.

In utero cardiac injection of mouse embryos

Briefly, pregnant mice were anesthetized and subjected to a laparotomy, the uterus exposed, and then a fenestrated dish was placed over the mouse and a single embryo (one uterine saccule) brought through the fenestration (Supplemental Fig. S1). The ultrasound microscope probe is used to guide the injection apparatus. A glass needle is used to inject the heart with fluorescein-conjugated tomato lectin (TL). The lectin is injected in a low volume and under low pressure to allow it to be passively carried in the blood wherever embryonic blood is normally flowing. Each embryonic heart was injected with 2.5 – 5.0 μl, depending on the age of the embryo. This procedure can be repeated for multiple embryos in the same pregnant mouse. The injected fluorescent-conjugated lectin is allowed to circulate for 10 minutes while it binds to the endothelial wall of the vasculature, after which the embryo is harvested, photographed and fixed in 4% PFA for immunofluorescent analyses.

Tissue Oxygenation measurement

Tissue oxygenation through oxidized thiol measurement was performed as described previously (Mastroberardino, et al., 2008). For tissue that was utilized for oxidized thiol detection, the free thiols in the harvested tissue were immediately blocked by performing all dissections in PBS with 100mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) and 100mM iodacetamide (IAM) (Sigma Aldrich). The isolated pancreas was then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde containing 100mM NEM and 100mM IAM for 4 hours. After embedding and sectioning the tissue, disulfides were reduced with 4mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) (Sigma Aldrich) in PBS for 30 minutes. Reduced thiols were then labeled with 7-diethylamino-3-(4’-maleimidylphenly)-4-methylcoumarin (CPM) (Sigma Aldrich) during a 30 minute incubation period. After this step, routine immunohistochemistry was carried out on the tissue samples.

RESULTS

Embryonic pancreatic vascularity and blood flow

Whole mount immunohistochemistry of E12.5–E17.5 pancreas for the endothelial marker Pecam showed a dense vasculature throughout (Fig. 1A–C). This dense vascularity would suggest that the developing pancreas is well-perfused with blood. However, in order to directly evaluate blood flow in the embryonic pancreas (as opposed to the mere presence of blood vessels and/or endothelium) we developed a method of survivable in utero embryonic mouse intracardiac injection. This embryonic intracardiac injection is guided by high resolution ultrasound biomicroscopy (Figs. 1D, Supplemental Figs. S1, S2 and Video S1) and can be performed as early as E9.5, the time when the embryonic pancreas first evaginates from the foregut. Previous techniques have been used to access the cardiovascular system of mouse embryos, but either later in gestation (E14.5) for survivable injections (Peranteau et al., 2007), or else early in gestation (E11.5) but ex vivo, with immediate sacrifice of the embryo (Sugiyama et al., 2003). In our system a midline laparotomy is performed on a pregnant mouse between gestational ages E9.5 and E17.5, and a single uterine saccule is exposed (Supplemental Fig. S1). Ultrasound biomicroscopy is then used to identify the embryonic heart through the uterine wall. A 30μm drawn-glass beveled capillary pipette is inserted into the left ventricle of the embryonic heart (the E11 heart has an end-diastolic left ventricular volume of 160 nanoliters) (Tanaka et al., 1997), and then the heart is injected with 0.2–5μl of a vascular tracer. We have used fluoresceine isothiocynate (FITC)-conjugated tomato lectin (volume depending on age of the embryo), an endothelial cell marker that labels vessels that are being perfused by the embryonic circulation (McDonald and Choyke, 2003), as well as FITC-labeled dextran. The embryonic heart then pumps the tracer throughout the embryo to delineate which vessels are being perfused with blood. After the injection the heart is observed for possible bleeding or contractile dysfunction. In some cases, the laparotomy is closed and the injected embryos are allowed to develop normally (Supplemental Fig. S3), even into adult life. Post-injection survival to birth is approximately 60–80%, depending on age (data not shown). The intracardiac injection of FITC-tomato lectin revealed a whole embryo “angiogram” of perfused vessels (Fig. 1E, Supplemental Fig. S2), with large vessels and secondary branches throughout the embryo well-visualized. By comparing FITC-tomato lectin-marked vessels (i.e., vessels receiving embryonic blood flow) with immunostaining for a general marker of vascular endothelium (Pecam), we identified numerous vessels early in gestation that were not receiving blood flow (non-perfused) (Figure 1F–J).

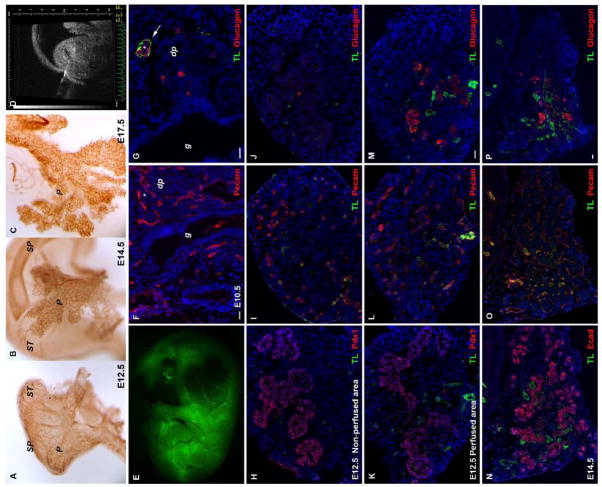

Figure 1. Embryonic pancreas is vascularized early during development.

Whole-mount immunohistochemistry analyses of E12.5 (A), E14.5 (B), and E17.5 (C) pancreas using antibodies against Pecam reveals that it is highly vascularized. (D) Ultrasound backscatter image of an E12.5 embryo with the echo-bright needle tip in the heart. (E) After in utero injection of the embryonic heart (at E12.5) with the endothelial tracer FITC-tomato lectin, a whole embryo “angiogram” of perfused vessels is demonstrated. (F,G) Histologic sections of an E10.5 embryo demonstrate that there is scant perfusion with tomato lectin (TL) in the region of the dorsal pancreas (dp) and gut (g), but there are numerous unperfused vessels (Pecam+). The arrow in (G) indicates a glucagon-positive area in the dorsal pancreas that has significant perfusion. (H–M) At E12.5 there is a regionalization within the pancreas, with areas that receive detectable blood flow and that also show glucagon+ differentiation (K–M), and then other unperfused areas (H–J) that lack glucagon+ differentiation. (N–P) Perfusion of an early E14 pancreas is more diffuse compared with the regional perfusion at E12.5, but still only a subset of the Pecam+ vessels are perfused (O,P). Again, glucagon-positive cells are only in the vicinity of the tomato-lectin perfused vessels (P), whereas numerous E-cadherin+ (Ecad) cells are in the vicinity of unperfused vessels (N,O).

In the early developing pancreas, there was a clear distinction between perfused vessels (FITC-tomato lectin+/Pecam+ double-positive) and non-perfused vessels (FITC-tomato lectin-negative/Pecam+) (Fig. 1). To confirm this regionalization of blood flow, with a general lack of flow to most of the mesenchyme, we injected 250,000MW FITC-tagged dextran (smaller-sized dextran molecules leaked out of the vessels, making interpretation of the images difficult), which showed a similar pattern as FITC-tagged lectin (Supplemental Fig. S4). The dextran signal was difficult to recover after fixation, and therefore we used lectin imaging for the remainder of the studies. At E10.5 the vast majority of the Pecam+ vascular endothelium was not double-stained with FITC-tomato lectin, and therefore was likely not perfused with a significant amount of blood (Figs. 1F,G). It is possible that trace amounts of blood are flowing to these tomato lectin-negative vascular regions, but this low level of flow would be below the sensitivity of our fluorescence imaging system. However, our system is definitely sensitive enough to detect normal capillary blood flow, since in other tissues (Supplemental Fig. S4) and in older embryos (E14–15) lectin-positive vessels, including capillaries, are seen throughout the vasculature (few Pecam+/lectin-negative blood vessels are present, see Figs. 2E–H).

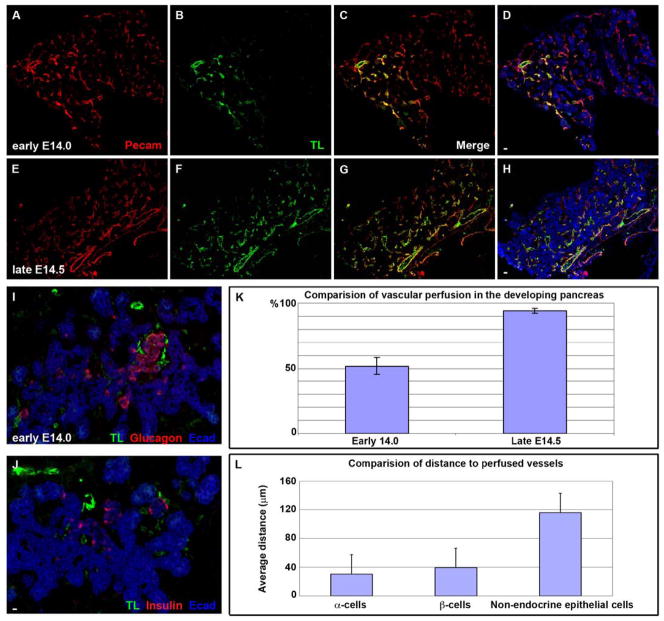

Figure 2. Pancreatic cell differentiation coincides with embryonic blood flow perfusion.

(A–H) A transition appears to occur between early E14 (A–D) and late E14 (E–H) wherein the percentage of vessels receiving blood flow increases substantially such that nearly all vessels become tomato lectin+ (compare A and B with E and F, quantified in K). (I,J) Confocal images of an early E14 pancreas demonstrate the specific regionalization of endocrine cells (both insulin+ and glucagon+ cells) to the vicinity of perfused vessels (tomato lectin+, TL+). Those epithelial regions in which FITC-tomato lectin−/Pecam+ (non-perfused) vessels predominate were notably endocrine-negative. E-cadherin staining in I and J demonstrates the large area of unperfused pancreatic epithelium. I and J represent adjacent sections of the same tissue sample. (K) Comparative linear quantification of the Pecam and tomato-lectin areas demonstrating the increase that occurs in the percentage of vessels that are perfused over this period of transition from early to late e14 (error bars SEM, N=10 pancreases, P<.001). (L) Morphometric analysis of the distance between differentiating endocrine cells (α-cells or β cells) and the nearest perfused vessel versus undifferentiated E-cadherin+ cells (error bars SEM, N=100 cells, P<.001 between either alpha or beta cells and non-endocrine epithelial cells). TL – FITC-tomato lectin, E-cad – E-cadherin.

To better visualize blood flow to the embryonic pancreas, we used confocal Z-stack imaging and morphometric software to create a three-dimensional image of an E11.5 pancreas after FITC-tomato lectin intracardiac injection (Supplemental Fig. S5, and Video S2). Staining for glucagon, Pecam, and a marker of embryonic pancreatic epithelium (Sox9) demonstrate that blood flow (FITC-tomato lectin) appears to enter on one side of the pancreas, and fans out to cover the epithelium. Most of this blood flow appears to be directed toward the epithelial region where glucagon is expressed (Supplemental Figs. S5, A–D). At this E11.5 age there are very few insulin-positive cells present. Despite the presence of a three-dimensional network of Pecam+ vessels, there appears to be minimal blood flow to the vessels in the vicinity of the mesenchyme (Sox9-negative/glucagon-negative) and the undifferentiated epithelium (Sox9+)(Supplemental Figs. S4, D–F and S5, E–H), and thus much of the pancreatic vasculature is not receiving blood flow at E11.5 (yellow-only Pecam+ cells in Supplemental Figs. S5, I–L).

Interestingly, the region of the early pancreas (E10.5–E11.5) that was clearly perfused with blood was in the vicinity of the few glucagon-positive cells that are normally present at this early stage of pancreatic development. Here, it is important to note that there was diffuse Pecam+ endothelium throughout the mesenchyme of the early embryonic pancreas, most of which was not receiving blood flow. Similarly, others have shown diffuse VEGFR2+ endothelium throughout the mesenchyme of the embryonic pancreas at this age as well (Lammert et al., 2001). This non-perfused endothelium did not, however, seem to induce the adjacent pancreatic epithelium to undergo differentiation. Between E10.5 and E14 the number of pancreatic vessels that were perfused with blood (FITC-tomato lectin+/Pecam+ double-positive vascular endothelium) slowly increased (Fig. 1H–P). During E12.5–E14 glucagon-positive cells tended to localize specifically near perfused blood vessels (Figs. 1M,P, and compare the non-perfused regions of the E12.5 pancreas in figure 1J with the perfused areas in Fig. 1M). By early E14 insulin-positive cells also tended to localize near blood flow, similar to the glucagon-positive cells (Fig. 2J).

As late as E14 the percentage of Pecam+ vessels that were perfused (FITC-tomato lectin+) was still only around 50% (Figs. 2A–D, K). Interestingly, just a short time later (late E14/early E15) there was a substantial increase such that over 90% of the pancreatic vascular endothelium became FITC-tomato lectin+ (compare Figs. 2A–D with 2E–H, and see Fig. 2K). Early E14 embryos can be distinguished from late E14 by well-defined external characteristics of the embryo. This relatively sudden transition from selective regional blood flow in the earlier developing pancreas (E10.5 through early E14), to global pancreatic perfusion (starting at late E14/early E15), corresponds approximately to a time of rapid increase in the amount of amylase-positive exocrine differentiation (Pictet et al., 1972; Rall, et al., 1973, Zhou et al., 2007).

To assess any correlation between regional blood flow and pancreatic epithelial cell differentiation, examination of intracardiac-injected embryos from E11.5 to E15.5 confirmed that prior to E14.5, glucagon+ or insulin+ cells were generally localized to regions of the developing pancreas where blood was flowing (Figs. 1H–P and 2I–L). Some areas that were receiving blood flow did not have adjacent endocrine-positive cells, which could represent new blood flow to regions that had not yet undergone endocrine differentiation. Regions of the developing pancreas that had FITC-tomato lectin−/Pecam+ (non-perfused) vessels were generally endocrine-negative, suggesting that the presence of endothelium alone, in the absence of blood flow, is insufficient to induce differentiation. Morphometric analyses of tissue sections showed that the distance between differentiated cells (endocrine-hormone positive) and the nearest perfused vessel at early E14.5 was 3-to-4-fold less than the distance between undifferentiated non-mesenchymal pancreatic cells (E-cadherin+/endocrine-negative cells) and the nearest perfused vessels (Fig. 2L).

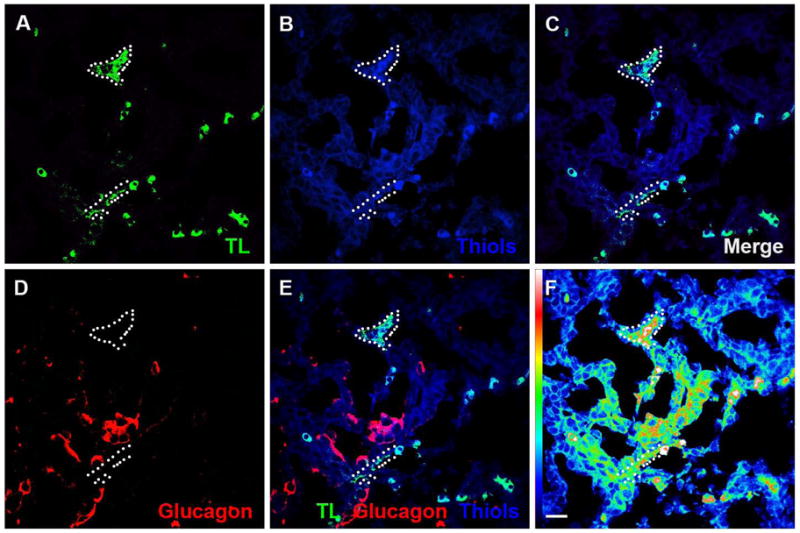

Oxygen is a key factor in orchestrating pancreatic cell differentiation

Enhanced oxygen delivery after the inflow of blood would seem a likely permissive factor for initiating differentiation. First, to confirm that tissue oxygenation is indeed enhanced in the vicinity of embryonic blood flow, we used a relatively new technique to detect oxidized thiols in histological samples (Mastroberardino et al., 2008). In states of higher tissue oxygenation thiols exist as oxidized disulfides (Yang et al., 2007). We found that the region around perfused (FITC-tomato lectin+) vessels had more oxidized thiols compared to the rest of the embryonic pancreas, representing a higher level of tissue oxygenation (Figs. 3A–F). These findings confirm that the region of the pancreatic epithelium that is adjacent to what we identified as “perfused” vessels in the developing embryo were in fact less hypoxic than regions further away from those perfused vessels, implying that the observed tomato lectin staining is indeed indicative of where blood is flowing. Similar to the discussion in the last section, while not all perfused and oxygenated areas are endocrine, the endocrine areas tended to be areas with flow and higher oxygenation, though exact quantification here would be difficult. Some endocrine-negative areas are well-oxygenated, again suggesting perhaps recent onset of blood flow to cells that are still early in the differentiation process.

Figure 3. Oxygenation and blood flow in the developing pancreas.

(A–C) Oxidized thiols were used to identify areas of higher tissue oxygenation. Regions with perfused FITC-tomato lectin+ (TL) vessels (A) showed higher levels of oxidized thiols (B,C). (D,E) Pancreatic epithelium, including glucagon-positive differentiated cells, adjacent to FITC-tomato lectin+ vessels also showed higher levels of oxidized thiols as compared to the surrounding embryonic pancreas. (F) An intensity “heat” map for oxidized thiol staining is a more sensitive method for assessing the gradient of tissue oxygenation, with decreasing oxygen tension seen with increasing distance from perfused vessels. TL – FITC-tomato lectin, Gluc – Glucagon, Thiols – Oxidized thiols.

Direct analysis of embryonic pancreatic differentiation in hypoxia

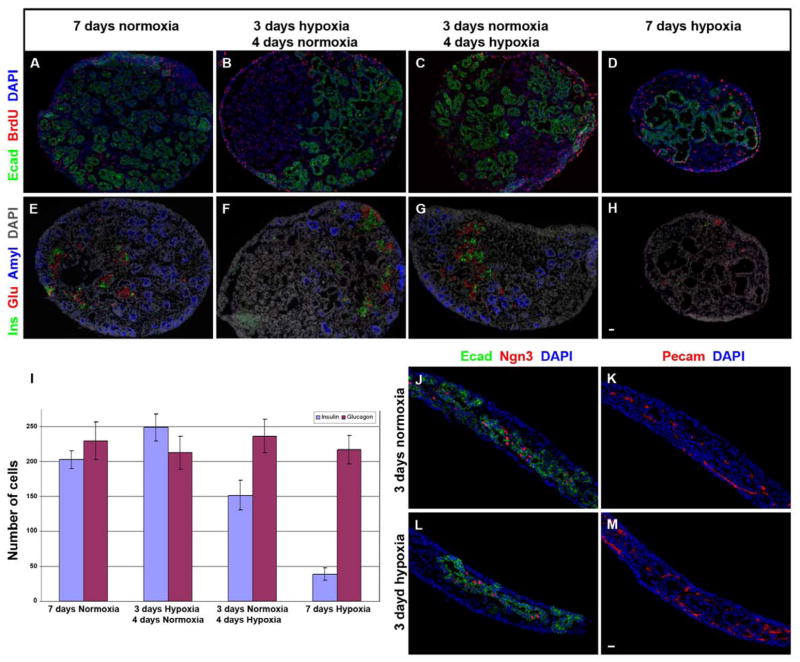

To directly study the effect of oxygen tension on pancreatic differentiation, we cultured E11.5 pancreatic explants in vitro in hypoxia (1% oxygen, a level we estimate would exist in unperfused regions of the embryonic pancreas (Meschia, 2004 and see Discussion section). Here, proliferation was maintained ( as measured by the fraction of BrdU+ cells, data not shown) in 1% oxygen compared with 21% oxygen (Fig. 4, compare A with D), but with little exocrine differentiation and little or no additional endocrine differentiation beyond the number of glucagon cells that were present at the start of the culture (Fig. 4, compare E with H, and J with L, and see 4I). The endocrine cells that were present after 7 days in hypoxia were essentially all glucagon-positive, and the number of glucagon-positive cells present after the 7-day culture period was roughly the same as had originally been present in the E11.5 pancreas at the time of harvesting and initiating the culture (data not shown). Very few insulin-positive cells developed in 1% oxygen. Thus, the robust growth of endocrine and exocrine cells that occurs in 21% oxygen cultures does not occur when grown in hypoxia. The poor differentiation in hypoxia occurs despite normal numbers of Pecam+ vessels (Fig. 4K,M), again suggesting that vascular endothelium by itself is not sufficient to induce pancreatic differentiation. In addition, the number of ngn3+ cells appears not to differ in the different oxygen concentrations, suggesting that there is not a loss of endocrine progenitors in hypoxia (Fig. 4J, L,).

Figure 4. Hypoxia allows maintained proliferation and an arrest of pancreatic differentiation.

A comparison of pancreas explants grown for 7 days in 21% oxygen culture conditions (A,E,I) or in hypoxia (1% oxygen) (D,H,L). Proliferation (BrdU staining) is maintained in hypoxia (A compared with D), but differentiation is blunted (E compared with H, L). In order to mimic the in utero increase in pancreatic blood flow that we observed at E14.5, E11.5 pancreases were cultured in 1% oxygen for 3 days, followed by 4 days of 21% oxygen (B,F), or with the reverse sequence as a control (C,G). By reproducing the in vivo blood flow transition and culturing the pancreas explants in three days of hypoxia followed by four days of 21% oxygen (B,F) endocrine and exocrine differentiation were rescued to the same or higher levels as in 21% oxygen-cultured explants (I). Quantification of these data is shown in (I) (error bars are SEM, N=5 explants for each group, no difference between any glucagon-positive cell groups, including the number of glucagon cells present at harvest (data not shown), all insulin-positive groups differ with a p value of less than 0.05). Comparable numbers of neurogenin3+ cells in either hypoxic or 21% oxygen-grown explants harvested after 3 days (J,L) suggest that simple toxic effects of hypoxia on endocrine progenitors is not the reason for less endocrine cells. Cell differentiation in explants cultured under hypoxic conditions was impaired despite the presence of equivalent amounts of Pecam+ vascular endothelium (K,M). Ecad: E-cadherin, Ins: insulin, Glu: glucagon, Amyl: amylase, Ngn3: neurogenin3.

We then altered the in vitro culture system to mimic the in utero changes in pancreatic tissue oxygenation that may occur during a transition from low or limited blood flow to more diffuse blood flow (which in the pancreas appears to occur at E14–E15). We first cultured E11.5 pancreatic explants for three days in hypoxic conditions (to mimic the period from E11.5 to E14.5 when there is no blood flow to the region of progenitor cells), followed by a switch to the supraphysiologic 21% oxygen for four days (to mimic the influx of blood flow that occurs at E14.5 (Fig. 4B,F,I)). Embryonic blood clearly does not reach a level of 21% oxygen, but since we currently do not know the exact concentration of oxygen in the flowing blood of the embryonic mouse pancreas, we wished to at least ensure that the tissues were not still hypoxic. In this transitional culture from low to high oxygen we saw recovery of insulin-positive and amylase-positive cell differentiation. In fact, this approach of using 3-days of initial hypoxia actually led to a higher number of insulin-positive cells than the explants grown in 21% oxygen conditions for the entire 7 days. This increased number of insulin-positive cells suggests that an increased proliferation of endocrine progenitor cells during the initial 3-day hypoxia exposure may have specifically generated a larger number of β–cell progenitors, and then these progenitors were able to give rise to a greater number of β–cells after transitioning the cultures to 21% oxygen.

DISCUSSION

There is a fundamental lack of understanding of how organs in early mammalian embryos are able to form despite receiving little or no blood flow. The early embryonic tissues are relatively hypoxic since the early embryonic cardiovascular system is immature, and is therefore presumably incapable of delivering high volumes of blood to all tissues. In addition, the embryonic blood only receives oxygen secondarily, by avidly removing oxygen from the mother’s placental blood, but clearly providing less oxygen to tissues than in the post-natal state (Meschia, 2004). Despite this apparent obligate hypoxia, mammalian embryonic tissues are well-known to be able to undergo rapid proliferation.

Recent evidence indicates that oxygen tension is an important regulator of the differentiation of many embryonic tissue types. In particular, pancreatic differentiation, especially β-cell differentiation, has been shown to be inhibited in vitro by hypoxia (Heinis et al., 2010). A specific pro-insulin inductive role was shown for endothelial cells by Lammert, et al. in which isolated early mouse endoderm, cultured in combination with structures containing endothelial cells (i.e., dorsal aortae or umbilical artery), led to Pdx1 expression and insulin-positive differentiation in the endoderm (Lammert et al., 2001). This inductive effect of endothelium on pancreatic differentiation was independent of embryonic blood flow since these inductive effects were seen in vitro in the absence of blood flow. However, since these in vitro studies were performed in normal culture media and 21% oxygen, a possible in vivo (in utero) need for blood flow to supply permissive factors (nutrients and oxygen) would not have been detected. Endothelial cells are clearly necessary for pancreatic differentiation in vivo. Yoshitomi and Zaret showed that dorsal endoderm, genetically depleted of endothelial cells (Flk1 null mutant embryonic mice) required recombination with endothelium-containing wild-type aortae to allow Ptf1a expression (Yoshitomi and Zaret, 2004). Although it is devoid of blood flow, the in vitro environment does provide oxygen and CO2 exchange, as well as other nutrients, so in the actual in utero environment both endothelium and nearby blood flow together may together be necessary for pancreatic differentiation.

Our findings suggest that blood flow plays an important permissive role in pancreatic differentiation in vivo, presumably by delivering oxygen and other nutrients, and that blood flow is not distributed evenly over the entire early embryonic pancreas. A role for blood-borne oxygen in regulating pancreatic differentiation (as opposed to vascular endothelium alone being sufficient to induce differentiation) is supported by findings in zebrafish where vascular endothelium was not necessary for pancreatic development (Serluca et al., 2002). Early developing zebrafish organs acquire oxygen by direct diffusion from the environment, without endothelium; in contrast, mammalian embryos require a functional cardiovascular system early in development to bring oxygen to the tissues (Baldessari and Mione, 2008; Zoeller et al., 2008). Our results also support the in vitro data from Heinis et al. in which higher oxygen tensions led to greater β–cell differentiation in embryonic pancreatic explant cultures in a collagen gel (Heinis et al., 2010).

One concern with our analysis of vascular perfusion in the embryos is that the in utero injection process may “stun” the embryonic cardiovascular system due to direct manipulation of the heart, hypothermia during the injection, varying hemodynamic properties of the injectate (e.g. hyperviscosity), etc. Such altered physiology could lead to inadequate perfusion pressure of the embryonic vessels, and thus a falsely low perceived level of perfusion. Thus, we performed high pressure embryonic intracardiac injections ex vivo with grossly supra-physiologic volumes of low viscosity injectate. Even with these supra-physiologic high pressure injections in the early embryos we were not able to achieve significant additional flow to the “unperfused” areas, despite inducing numerous punctate hemorrhages, presumably due to high pressure (data not shown). These results suggest that decreased embryonic perfusion pressure during the injection is less likely to be the cause of any perceived lack of perfusion of existing vessels. In addition, the oxidized thiol data (Figure 3) support that the regions demonstrating blood flow in our system were better oxygenated, implying that we were not seeing a “false-negative” for blood flow in other regions of the pancreas.

We found that in vitro the hypoxic embryonic pancreas is still proliferative, but does not differentiate. The recent findings by Heinis et al. that HIF1α is present and active in hypoxic tissues, and then is presumably degraded upon increased oxygenation, could be an additional pathway involved in pancreatic differentiation. Growth of embryonic pancreatic explants in 1% oxygen may have led to an expansion of progenitor cells, since subsequent transfer to 21% oxygen led to a greater number of β-cells than explants kept in 21% oxygen for the entire culture period. Unlike the previous study by Heinis, where 3% oxygen was used as hypoxia, 1% oxygen may be more representative of regions of the embryonic pancreas that are remote from blood flow. Normal oxygenated mammalian maternal blood is typically in the range of 12% oxygen (Meschia, 2004). However, at best in the fetus (“best” meaning a late-gestation fetus, which has a mature cardiovascular system) the peripheral fetal arterial blood oxygenation is only about one-fourth that of the maternal blood, or an approximate oxygen concentration of 3%. This step-down between maternal and fetal blood oxygenation is due first to the obvious step-down that must occur with the oxygen gradient across the placenta, and then secondly and more importantly, because of the normal fetal/embryonic anatomical mixing (only a fraction of the fetal cardiac output goes through the placenta, as opposed to post-natal circulation where almost all of the blood flows through the lungs). With a fetal or embryonic arterial oxygen content of 3% at the most (and likely lower in a more immature fetus or embryo because of an immature cardioplacental circulation), then there will be a further step-down in oxygen concentrations in the surrounding tissues, with tissues of course being more and more hypoxic as the distance of the tissue from the blood increases. Thus, we chose the 1% oxygen level as our best estimate of an unperfused area of the early embryonic mouse pancreas.

Interestingly, although insulin-positive cell numbers were greatly affected by oxygen tension in the explant culture experiments, the number of glucagon-positive cells was not, with no change in the number of glucagon-positive cells in the explant from the start of the culture period to the end, regardless of whether the explants were grown in 21% oxygen or 1% oxygen. These results suggest that our culture conditions are not conducive to new α-cell formation. In vivo, however, glucagon cells were primarily localized only to regions receiving blood flow, suggesting that new glucagon-positive cell formation in vivo, like β-cell formation, is dependent on oxygen.

The striking lack of perfusion of much of the vascular network in the early embryonic pancreas was unexpected. Several explanations are possible for the lack of perfusion of these vascular beds. First, early in development there may be no anatomical connection between the main embryonic vessels (which carry blood flow) and the numerous small vessels that do not have blood flow. In order for blood flow to reach these smaller vessels, connections (anastomoses) would need to develop between the larger main vessels and the smaller branches. A second possible explanation is that there is some restriction of blood flow to the vast network of small vessels, perhaps through a sphincteric mechanism. However, the ex vivo high pressure injections described above would suggest otherwise. A third possible explanation for not detecting flow to these vessels is that there actually is blood flow to these small vessels, but at a very low level that is not detectable by lectin (or FITC-labeled dextran) labeling. Late in gestation (E14–15), however, we did see that all vessels, including small capillaries, were well-demonstrated by lectin injections into the heart.

Teleologically, it makes sense that there are large vascular beds in the early embryo that are not receiving blood flow. Mammalian organogenesis has been shown to be closely coupled with vasculogenesis in several organs. This co-development of organ-specific cells and their accompanying vasculature would seem necessary for optimal alignment of the developing capillaries and epithelium to allow proper physiological function. For example, embryonic pulmonary capillaries develop in close association with the branching epithelium of the lung. This close association is critical for maximizing the interface of alveoli with pulmonary capillaries to optimize gas exchange. Similar to our findings in utero in the pancreas, dye injection studies have shown that the large embryonic pulmonary capillary network is, for the most part, unperfused until later in gestation (deMello et al., 1997). This lack of perfusion of capillary beds may be common to many developing organs in the embryo, which may be advantageous because of the immature early embryonic heart that presumably has limited cardiac output. Such a selective capillary bed perfusion system could reserve the limited cardiac output and blood flow for only those tissues where it is needed.

Our studies also demonstrate survivable access to the early mammalian embryonic vascular system in utero. We can now deliver large reagents (that would not otherwise cross the placenta, including viral and plasmid constructs, large proteins, etc.) directly and systemically to the early embryo, without relying on trans-placental transport from the mother (survivable injections can be done as early as E9.5). Such access may have important implications for future mammalian development studies, including direct manipulations of early organogenesis during or even before the actual process of organogenesis.

Our results show that vascular flow, rather than just vascular endothelium alone, may provide specific signals necessary for regional pancreatic differentiation in the early embryo. Vascular endothelium, blood flow, and blood-borne oxygen may also play a similar role in the development and differentiation of other organs.

Supplementary Material

A video of an in utero intracardiac injection in an E12.5 mouse is shown. The drawn-glass pipette is inserted through the outer uterine wall and advanced into the embryonic heart. The injectate (fluorescent tomato lectin in this example) is then injected directly into the embryonic vascular system and allowed to circulate by the embryo’s normal cardiac contractions.

Video of rotating three-dimensional image allows a better appreciation of the diffuse presence of the pecam+ blood vessels, but the specific association of the perfused vessels with the epithelium, and especially the endocrine cells (color scheme the same as Supplemental Figure 5)

Supplemental Figure S1. High resolution ultrasound biomicroscope and microinjection set-up. (A) During in utero embryonic mouse intracardiac injections a midline laparotomy is performed on the pregnant mouse and a single uterine saccule is brought out through the midline incision. (B) An ultrasound microscope probe is then placed over the saccule and a microinjection system is used to inject the embryonic heart.

Supplemental Figure S2. Higher resolution images of ultrasound image of the heart (A) with needle in the ventricle (arrow). B–D images of trunk, head, and limb (respectively) of E12.5 embryo 10 minutes after FITC-tomato lectin injections.

Supplemental Figure S3. In utero embryonic mouse intracardiac injection is survivable. After performing in utero embryonic mouse intracardiac injections the laparotomy can be closed and the injected embryos can develop normally. Here a mouse embryo was injected with 6μm fluorescein-incorporated microspheres at E12.5 and then allowed to develop normally, and harvested at E16.5. Numerous fluorescein-incorporated microspheres are seen distributed throughout the liver and in the intracardiac injection tract (arrow).

Supplemental Figure S4. (A–C): Cy3-Dextran (red) injections show a similar pattern as the tomato lectin in Supplemental Figure S2. (A) Whole E11.5 embryo; (B) Detail of E11.5 head vessels demonstrates fine vascular/capillary flow that is already established by E11.5; (C) Stomach shows well-perfused latticework of vessels/capillaries in the wall; (D–F): E11.5 pancreas shows perfusion focused to the region of the epithelium. (D): Phase contrast demonstrates the epithelium (e, outlined in white dashed line) and surrounding mesenchyme (m); (E, and overlay in F) FITC-Dextran (green) shows perfusion of the pancreas localized to the region of the pancreatic epithelium.

Supplemental Figure S5. Three-dimensional reconstruction of E11.5 pancreas after trans-uterine intracardiac injection of FITC-tomato lectin (See along with Video 2). Verticle columns represent sequential confocal sections through the pancreas stained for glucagon (red) and tomato lectin (green) in A–C, sox9 (dark blue) and pecam (light blue) in E–G, and a merge of glucagon (purple), pecam (yellow), sox9 (blue), and tomato lectin (green) in panels I–K. The three-dimensional image is shown for each at the bottom (D,H,L, and see Video S2). The blood appears to flow in from one side (arrow in A), and flows around the epithelium, with a relatively small amount of flow to the mesenchyme (arrow in D).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the NIH (GKG, RO1 DK064952, R01 DK083541-01), Pennsylvania State Tobacco Fund (GKG), and the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh for financial support. Thanks to Jessica Thomas, Sean-Paul Williams, and Chris Kalinyak for technical support. Csaba Galambos for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baldessari D, Mione M. How to create the vascular tree? (Latest) help from the zebrafish. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;118:206–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deMello DE, Sawyer D, Galvin N, Reid LM. Early fetal development of lung vasculature. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16:568–81. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.5.9160839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esni F, Johansson BR, Radice GL, Semb H. Dorsal pancreas agenesis in N-cadherin- deficient mice. Dev Biol. 2001;238:202–12. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esni F, Miyamoto Y, Leach SD, Ghosh B. Primary explant cultures of adult and embryonic pancreas. Methods Mol Med. 2005;103:259–71. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-780-7:259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esni F, Taljedal IB, Perl AK, Cremer H, Christofori G, Semb H. Neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) is required for cell type segregation and normal ultrastructure in pancreatic islets. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:325–37. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraker CA, Alvarez S, Papadopoulos P, Giraldo J, Gu W, Ricordi C, Inverardi L, Dominguez-Bendala J. Enhanced oxygenation promotes beta-cell differentiation in vitro. Stem Cells. 2007;25:3155–64. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittes GK. Developmental biology of the pancreas: a comprehensive review. Dev Biol. 2009;326:4–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebrok M, Kim SK, Melton DA. Notochord repression of endodermal Sonic hedgehog permits pancreas development. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1705–13. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinis M, Simon MT, Ilc K, Mazure NM, Pouyssegur J, Scharfmann R, Duvillie B. Oxygen tension regulates pancreatic beta-cell differentiation through hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Diabetes. 2010;59:662–9. doi: 10.2337/db09-0891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammert E, Cleaver O, Melton D. Induction of pancreatic differentiation by signals from blood vessels. Science. 2001;294:564–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1064344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastroberardino PG, Orr AL, Hu X, Na HM, Greenamyre JT. A FRET-based method to study protein thiol oxidation in histological preparations. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:971–81. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald DM, Choyke PL. Imaging of angiogenesis: from microscope to clinic. Nat Med. 2003;9:713–25. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peranteau WH, Endo M, Adibe OO, Flake AW. Evidence for an immune barrier after in utero hematopoietic–cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;109:1331–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-018606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pictet R, Rutter WJ. Development of the embryonic endocrine pancreas. Washington DC: Williams and Wilkins; 1972. pp. 25–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rall L, Pictet R, Williams R, Rutter WJ. Early differentiation of glucagon-producing cells in embryonic pancreas: a possible developmental role for glucagon. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1973;70:3478–3482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.12.3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meschia G. Placental respiratory gas exchange and fetal oxygenation. In: Creasy R, et al., editors. Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Elsevier; 2004. pp. 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Serluca FC, Drummond IA, Fishman MC. Endothelial signaling in kidney morphogenesis: a role for hemodynamic forces. Curr Biol. 2002;12:492–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00694-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama D, Ogawa M, Hirose I, Jaffredo T, Arai K, Tsuji K. Erythropoiesis from acetyl LDL incorporating endothelial cells at the preliver stage. Blood. 2003;101:4733–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Mao L, DeLano FA, Sentianin EM, Chien KR, Schmid-Schonbein GW, Ross J., Jr Left ventricular volumes and function in the embryonic mouse heart. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H1368–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.3.H1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Song Y, Loscalzo J. Regulation of the protein disulfide proteome by mitochondria in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10813–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702027104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshitomi H, Zaret KS. Endothelial cell interactions initiate dorsal pancreas development by selectively inducing the transcription factor Ptf1a. Development. 2004;131:807–17. doi: 10.1242/dev.00960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Law AC, Rajagopal J, Anderson WJ, Gray PA, Melton DA. A multipotent progenitor domain guides pancreatic organogenesis. Dev Cell. 2007;13:103–14. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoeller JJ, McQuillan A, Whitelock J, Ho SY, Iozzo RV. A central function for perlecan in skeletal muscle and cardiovascular development. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:381–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A video of an in utero intracardiac injection in an E12.5 mouse is shown. The drawn-glass pipette is inserted through the outer uterine wall and advanced into the embryonic heart. The injectate (fluorescent tomato lectin in this example) is then injected directly into the embryonic vascular system and allowed to circulate by the embryo’s normal cardiac contractions.

Video of rotating three-dimensional image allows a better appreciation of the diffuse presence of the pecam+ blood vessels, but the specific association of the perfused vessels with the epithelium, and especially the endocrine cells (color scheme the same as Supplemental Figure 5)

Supplemental Figure S1. High resolution ultrasound biomicroscope and microinjection set-up. (A) During in utero embryonic mouse intracardiac injections a midline laparotomy is performed on the pregnant mouse and a single uterine saccule is brought out through the midline incision. (B) An ultrasound microscope probe is then placed over the saccule and a microinjection system is used to inject the embryonic heart.

Supplemental Figure S2. Higher resolution images of ultrasound image of the heart (A) with needle in the ventricle (arrow). B–D images of trunk, head, and limb (respectively) of E12.5 embryo 10 minutes after FITC-tomato lectin injections.

Supplemental Figure S3. In utero embryonic mouse intracardiac injection is survivable. After performing in utero embryonic mouse intracardiac injections the laparotomy can be closed and the injected embryos can develop normally. Here a mouse embryo was injected with 6μm fluorescein-incorporated microspheres at E12.5 and then allowed to develop normally, and harvested at E16.5. Numerous fluorescein-incorporated microspheres are seen distributed throughout the liver and in the intracardiac injection tract (arrow).

Supplemental Figure S4. (A–C): Cy3-Dextran (red) injections show a similar pattern as the tomato lectin in Supplemental Figure S2. (A) Whole E11.5 embryo; (B) Detail of E11.5 head vessels demonstrates fine vascular/capillary flow that is already established by E11.5; (C) Stomach shows well-perfused latticework of vessels/capillaries in the wall; (D–F): E11.5 pancreas shows perfusion focused to the region of the epithelium. (D): Phase contrast demonstrates the epithelium (e, outlined in white dashed line) and surrounding mesenchyme (m); (E, and overlay in F) FITC-Dextran (green) shows perfusion of the pancreas localized to the region of the pancreatic epithelium.

Supplemental Figure S5. Three-dimensional reconstruction of E11.5 pancreas after trans-uterine intracardiac injection of FITC-tomato lectin (See along with Video 2). Verticle columns represent sequential confocal sections through the pancreas stained for glucagon (red) and tomato lectin (green) in A–C, sox9 (dark blue) and pecam (light blue) in E–G, and a merge of glucagon (purple), pecam (yellow), sox9 (blue), and tomato lectin (green) in panels I–K. The three-dimensional image is shown for each at the bottom (D,H,L, and see Video S2). The blood appears to flow in from one side (arrow in A), and flows around the epithelium, with a relatively small amount of flow to the mesenchyme (arrow in D).