Abstract

Mortality from stomach cancer has fallen steadily during the past decades. The aim of this paper is to assess the implication of a possible continuation of the decline in stomach cancer mortality until the year 2030. Annual rates of decline in stomach cancer mortality from 1980 to 2005 were determined for the Netherlands, United Kingdom, France, and four Nordic countries on the basis of regression analysis. Mortality rates were extrapolated until 2030, assuming the same rate of decline as in the past, using three possible scenarios. The absolute numbers of deaths were projected taking into account data on the ageing of national populations. Stomach cancer mortality rates declined between 1980 and 2005 at about the same rate (3.6–4.9% per year) for both men and women in all countries. The rate of decline did not level off in recent years, and it was not smaller in countries with lower overall mortality rates in 1980. If this decline were to continue into the future, stomach cancer mortality rates would decline with about 66% between 2005 and 2030 in most populations, while the absolute number of stomach cancer deaths would diminish by about 50%. Thus, in view of the strong, stable and consistent mortality declines in recent decades, and despite population ageing, stomach cancer is likely to become far less important as a cause of death in Europe in the future.

Keywords: Stomach cancer, Mortality, Trends, Europe, Projections

Introduction

Stomach cancer is the fourth most frequent cancer [1, 2] and the world’s second leading cause of cancer mortality [1]. However, it has been fallen throughout Europe during the past decades in terms of both incidence and mortality rates [3, 4], mainly as a result of remarkable improvement of living conditions in European societies [5–8]. Efforts to reduce global cancer disparities begin with an understanding of geographic patterns in cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence, by studies such as GLOBOCAN [9, 10], EUROCARE [11], and Five Continents databases [12]. Survival increased and mortality decreased through the combination of earlier detection, better access to care and improved treatment [13]. There has also been a concomitant change in lifestyle and environmental exposures over successive generations [14], including changes in exposures to risk factors in early life [15].

Several studies conducted projections of future trends in stomach cancer mortality in European countries [7, 12, 14–17]. Mortality rates were generally expected to decline further. Based on the cancer mortality trends in the European Union until 2000, one study projected a further fall by 11% in age-standardized cancer mortality from 2000 to 2015 [16]. A Dutch study also projected a substantial decline in stomach cancer mortality until 2015, based on trends until 2000 [17]. Similarly, an Irish study predicted mortality from stomach cancer to fall further in the near future, although at a slower rate than in the recent past [18].

European studies included projections of the absolute number of cancer deaths, thereby taking into account the rapid ageing of European populations in the forthcoming decades [14–16]. Population ageing alone may induce a strong increase in the absolute number of incident cases and deaths for many types of cancer. However, in the case of stomach cancer, this demographic effect may be offset by an opposite epidemiological effect if the recent decline in age-specific mortality rates were to continue in the future.

The aim of this study was to assess, for seven European countries, the implications of a possible continuation of the recent declines in stomach cancer rates. Future trends were evaluated in terms of not only mortality rates, but also absolute numbers of death, thereby taking into account the ageing of national populations.

Projections of future mortality trends should be based on a careful analysis of trends in the past [19, 20]. We therefore started the analysis with a description of trends in stomach cancer mortality over a long period, from 1980 up to 2005, in order to check whether mortality declines continued undiminished until recent years. In addition, we assessed whether the rate of decline was similar for all seven countries and both sexes, despite differences in overall levels of stomach mortality rates. We thus aimed to identify a stable and consistent long-term mortality trend that could serve as a basis for projections into the future. In addition, we formulated three scenarios to express uncertainties regarding future mortality trends.

Materials and methods

Data for Denmark, Finland, France metropolitan, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and England and Wales on the number of deaths from stomach cancer (ICD code 151 for ICD-8 and ICD-9, C16 for ICD-10 [21]) and corresponding numbers of population at risk, by sex and five-year age groups for the years 1980–2005 have been obtained from Eurostat (Denmark from 1999 to 2001, France from 1998–2005, and other countries from 2000 to 2005) and national data sources (1980–1999) [22]. The historical national data for England and Wales and France were transformed into data for United Kingdom and France metropolitan, by applying age and sex-specific correction factors, based on the comparison of stomach cancer mortality rates in 1995.

To describe trends in stomach cancer mortality between 1980 and 2005, sex-specific age-standardized mortality rates were calculated using direct standardization, taking the average national male and female populations by 5 year age groups over 2000–2005 (2000–2001 for Denmark) as the standard populations. In addition, we estimated sex- and country- specific annual mortality changes (%) over the period 1980–2005 by means of age-period log-linear regression analysis. The dependent variable was the number of deaths, with the person-years at risk (estimated by the midyear population) as offset variable. We used age by 5 year age groups (from 0 to 80 +) (categorical) and single calendar year (continuous) as independent variables. Annual mortality changes (%) were calculated by this formula: 100*(exp(b)-1), in which b is the parameter estimate of the calendar year variable.

To project age, sex, and country-specific mortality rates until 2030, we assumed that the mortality trends in the past 25 years (from 1980 to 2005) would continue for the coming 25 years. Therefore, we applied the estimated annual changes in mortality in the period 1980–2005 for all age groups combined to average national age-specific mortality rates in 2000–2005.

To express uncertainties regarding future mortality trends, we formulated three scenarios. In the reference scenario, the future rate of change was assumed to be equal for all countries and therefore was calculated as the unweighted average of the rates of change of the seven countries. In the pessimistic scenario, we assumed the future rate of change to be equal to the slowest observed rate of change observed among all countries. In the optimistic scenario, we took the highest rate of change observed in the past. All three scenarios distinguished men and women.

The formula used to make projections, per country and sex, was:  , where M denotes the mortality rate in the age interval x to x + n. De year t is expressed as the difference with the baseline year t0 (= 2005); thus t = 25 for the year 2030. The change factor c* is the observed annual decline (exp(b)-1) for all age groups combined, multiplied by a ratio expressing the annual decline in the age groups 40–59, 60–79, and 80 + relative to the annual decline for all age groups (unweighted average over all countries). In the reference scenario, the applied ratios for men were 0.92, 1.03, and 0.99 for the age groups 40–59, 60–79, and 80 and more, respectively; and the ratios for women were 0.85, 0.97, and 1.09, respectively.

, where M denotes the mortality rate in the age interval x to x + n. De year t is expressed as the difference with the baseline year t0 (= 2005); thus t = 25 for the year 2030. The change factor c* is the observed annual decline (exp(b)-1) for all age groups combined, multiplied by a ratio expressing the annual decline in the age groups 40–59, 60–79, and 80 + relative to the annual decline for all age groups (unweighted average over all countries). In the reference scenario, the applied ratios for men were 0.92, 1.03, and 0.99 for the age groups 40–59, 60–79, and 80 and more, respectively; and the ratios for women were 0.85, 0.97, and 1.09, respectively.

Future stomach cancer mortality numbers were estimated by applying the future sex and age-specific rates to the projected age-specific population sizes for the different countries up to 2030. These future population numbers have been obtained from Eurostat (baseline variant), except for Norway for which the data have been obtained from Statistics Norway (medium national Growth variant) (http://statbank.ssb.no/statistikkbanken). Looking into the projected mortality rates and absolute number of deaths in 2030, it can be measured if stomach cancer is a less important cause of death in the future.

Results

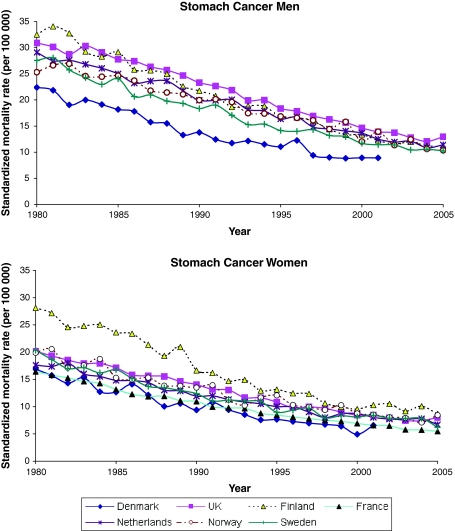

Figure 1 shows trends in age-standardized mortality rates between 1980 and 2005. In all countries, stomach cancer mortality rates declined steadily. The rate of decline is within a narrow range, from 3.61% per year for Norwegian men to 4.90% for Danish and Finnish women. The overall average rate of decline was 4.2% per year. The rate of decline remained similar over time for both sexes in most of these countries. There was no indication that the rate of decline (expressed in percent decline per year) had been levelling off in recent years. A main exception is the strong decline in mortality among Finnish women in the 1980s, when Finnish women were catching up with other countries.

Fig. 1.

Age-standardized stomach cancer mortality rates (per 100,000) in seven European countries by sex: 1980–2005 Corresponding estimates of annual declines (%) for men (women) are for Denmark 4.60 (4.90), United Kingdom 3.96 (4.16), Finland 4.68 (4.90), France Metropolitan 3.67 (4.32), Netherlands 3.92 (3.81), Norway 3.61 (3.90), and Sweden 4.06 (4.11)

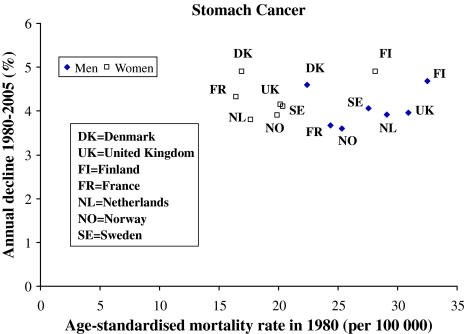

In Fig. 2, the rate of declines in stomach cancer mortality over the period 1980–2005 is plotted against the age-standardized mortality rates in 1980. The aim of this scatter plot is to assess whether the decline in stomach cancer mortality was higher in populations with higher initial mortality rates. However, both among men and women, no such positive association was found.

Fig. 2.

Annual declines (%) in stomach cancer mortality 1980–2005 against age-standardized mortality rates in 1980, by sex and country

Table 1 presents projections for 2030 of stomach cancer mortality rates. Values projected for 2030 are compared to values observed for 2005 by means of ratios with 2005 as reference. In all seven European countries, age-standardized mortality rates would have declined in 2030 compared to 2005 if past trends were to continue. This decline would be substantial in all populations. The average decline in mortality rates over the period 2005–2030 would for men amount to 66%, 59% and 75% for the reference, pessimistic, and optimistic scenarios, respectively. For women this would amount to 67%, 59% and 77% respectively.

Table 1.

Stomach cancer mortality rates (age standardized, per 100,000), by scenario, country and sex, for 2005 (observed) and 2030 (projected)

| Year | Country | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | United Kingdom | Finland | France | Netherlands | Norway | Sweden | ||

| Men | ||||||||

| Reference | 2005 | 7.40 | 12.95 | 11.09 | 9.87 | 11.40 | 10.37 | 10.27 |

| 2030 | 2.62 | 4.22 | 3.80 | 3.39 | 3.84 | 3.74 | 3.48 | |

| Scenario | 2030/2005a | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.34 |

| Pessimistic | 2030 | 3.21 | 5.06 | 4.60 | 4.10 | 4.62 | 4.52 | 4.21 |

| Scenario | 2030/2005a | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.41 |

| Optimistic | 2030 | 1.87 | 3.08 | 2.78 | 2.47 | 2.80 | 2.71 | 2.52 |

| Scenario | 2030/2005a | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.24 |

| Women | ||||||||

| Reference | 2005 | 4.73 | 8.02 | 8.69 | 5.49 | 6.70 | 8.44 | 6.22 |

| 2030 | 1.59 | 2.34 | 2.91 | 1.81 | 2.32 | 2.39 | 2.29 | |

| Scenario | 2030/2005a | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.37 |

| Pessimistic | 2030 | 2.00 | 2.90 | 3.62 | 2.26 | 2.89 | 2.99 | 2.85 |

| Scenario | 2030/2005a | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.46 |

| Optimistic | 2030 | 1.14 | 1.68 | 2.13 | 1.28 | 1.69 | 1.71 | 1.65 |

| Scenario | 2030/2005a | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.27 |

For Denmark, the values for 2005 are not observed but projected

Reference scenario = Equal future rate of change for all countries; Pessimistic scenario = Slowest observed rate of change for all countries; Optimistic scenario = Highest rate of change for all countries

aThe figure for 2030 divided by the related figure for 2005

Table 2 presents projections for 2030 of the absolute number of stomach cancer deaths. Values projected for 2030 are compared to values observed for 2005 by means of ratios with 2005 as reference. The decline in the absolute number of deaths would be substantial as well, although with more variability between countries. The average decline in deaths over the period 2005–2030 would for men amount to 43%, 32% and 59% for the reference, pessimistic, and optimistic scenarios, respectively. For women this would amount to 54%, 42% and 67% respectively.

Table 2.

Stomach cancer absolute numbers of deaths, by scenario, country and sex, for 2005 (observed) and 2030 (projected)

| Year | Country | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | United Kingdom | Finland | France | Netherlands | Norway | Sweden | ||

| Men | ||||||||

| Reference | 2005 | 209 | 3914 | 301 | 3045 | 963 | 242 | 470 |

| 2030 | 112 | 2050 | 186 | 1675 | 556 | 155 | 240 | |

| Scenario | 2030/2005a | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 0.51 |

| Pessimistic | 2030 | 137 | 2467 | 225 | 2090 | 667 | 186 | 291 |

| Scenario | 2030/2005a | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.62 |

| Optimistic | 2030 | 79 | 1480 | 133 | 1204 | 404 | 111 | 172 |

| Scenario | 2030/2005a | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.37 |

| Women | ||||||||

| Reference | 2005 | 131 | 2475 | 240 | 1789 | 566 | 196 | 284 |

| 2030 | 58 | 1021 | 119 | 877 | 290 | 81 | 138 | |

| Scenario | 2030/2005a | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.49 |

| Pessimistic | 2030 | 73 | 1266 | 148 | 1100 | 360 | 101 | 171 |

| Scenario | 2030/2005a | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.51 | 0.60 |

| Optimistic | 2030 | 41 | 725 | 84 | 606 | 209 | 58 | 98 |

| Scenario | 2030/2005a | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.37 | 0.30 | 0.35 |

For Denmark, the values for 2005 are not observed but projected

Reference scenario = Equal future rate of change for all countries; Pessimistic scenario = Slowest observed rate of change for all countries; Optimistic scenario = Highest rate of change for all countries

aThe figure for 2030 divided by the related figure for 2005

Discussion

The strong decline in stomach cancer mortality was found to continue at an undiminished rate until 2005 in each of the seven European countries. If this decline were to continue into the future, stomach cancer mortality rates would decline with about 66% between 2005 and 2030. The absolute number of stomach cancer deaths would diminish by about 50% despite the ageing of national populations. Even though weaker declines were predicted in the pessimistic scenario, this scenario as well implied that stomach cancer would become far less important as a cause of death in Europe in the next decades.

A key factor for the past declines in stomach cancer mortality is a decrease in the exposure to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection [23]. H. pylori prevalence had been found to decline in parallel with the decrease of incidence of stomach cancer [24]. However, H. Pylori infection may not be the only factor. It has been estimated to account for only half of the global total burden of stomach cancer because of synergistic or antagonistic roles of dietary and other exogenous factors [25]. Complementary explanations for the observed declines in stomach cancer mortality may include better food preservation and refrigeration, improvement in environmental conditions and lifestyle changes [26, 27]. Similarly, declines in the near future may still be largely driven by recent improvements in the living conditions that current generations had experienced during their childhood and adulthood.

Improved medical treatment may also have contributed to the decline in mortality from stomach cancer [26, 27] like it contributed to the observed differences in stomach cancer mortality between European countries [27]. Therefore, further advances in the treatment for stomach cancer and H. pylori infections may be important to maintain a strong decline in stomach cancer mortality rates in the future. This role is supported by the observation that, while the incidence of stomach cancer had declined as well, mortality rates seemed to have declined at faster rates, indicating a decline in case fatality rates [14]. However, we should note that different trends in incidence and mortality of cancer are found for most solid tumours, and may be a consequence of increased detection of early tumours with often good prognosis [28].

Empirical support for the expectation that the decline in mortality from stomach cancer will continue in the future comes from the trends that were observed for the past 25 years. Firstly, there is a strong consistency in the recent trends in stomach cancer mortality among both sexes and among each of the seven European countries. Second, these declines had persisted up to recent years in each of these populations, including those with the lowest initial mortality rates. Furthermore, steady declines in stomach cancer mortality were observed in the middle-aged and the young population as well, suggesting that they are likely to continue in the near future [4, 5, 16]. The latter observation is consistent with observations of cohort-wise patterns of decline in stomach cancer mortality in European countries [14, 29, 30], which may reflect the effects of improvement in living conditions in childhood [29].

It should be emphasized that, even though future declines may seem likely, our study was primarily aimed at exploring possible future trends by extrapolating past trends. This extrapolation provides a baseline scenario against which new studies may formulate more specific scenarios of future trends. For example, policy-based scenarios may focus on the potential effects of specific preventive policies or advancement in the treatment of stomach cancer. As stomach cancer may become ever less important in terms of mortality, scenario studies will need to also include measures of incidence, prognosis and prevalence of stomach cancer.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(3):354–362. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i3.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prinz C, Schwendy S, Voland P. H pylori and gastric cancer: shifting the global burden. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(34):5458–5464. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i34.5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelley JR, Duggan JM. Gastric cancer epidemiology and risk factors. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00534-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levi F, Lucchini F, Gonzalez JR, Fernandez E, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Monitoring falls in gastric cancer mortality in Europe. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(2):338–345. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosetti C, Bertuccio P, Levi F, Lucchini F, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Cancer mortality in the European Union, 1970–2003, with a joinpoint analysis. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(4):631–640. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lepage C, Remontet L, Launoy G, et al. Trends in incidence of digestive cancers in France. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17(1):13–17. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32809b4cba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levi F, Lucchini F, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Continuing declines in cancer mortality in the European Union. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(3):593–595. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(1):43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94(2):153–156. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francisci S, Capocaccia R, Grande E, et al. The cure of cancer: a European perspective. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(6):1067–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(14):2137–2150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karim-Kos HE, de Vries E, Soerjomataram I, Lemmens V, Siesling S, Coebergh JW. Recent trends of cancer in Europe: a combined approach of incidence, survival and mortality for 17 cancer sites since the 1990s. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(10):1345–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzsimmons D, Osmond C, George S, Johnson CD. Trends in stomach and pancreatic cancer incidence and mortality in England and Wales, 1951–2000. Br J Surg. 2007;94(9):1162–1171. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aragones N, Pollan M, Rodero I, Lopez-Abente G. Gastric cancer in the European Union (1968–1992): mortality trends and cohort effect. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7(4):294–303. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(97)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinn MJ, d’Onofrio A, Moller B, et al. Cancer mortality trends in the EU and acceding countries up to 2015. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(7):1148–1152. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coebergh JW. Kanker in Nederland: KWF kankerbestrijding; 2004: 88–94. Avalable from http://spitswww.uvt.nl/~Fmols/kanker_in_nederland.pdf.

- 18.O’Lorcain P, Deady S, Comber H. Mortality predictions for esophageal, stomach, and pancreatic cancer, Ireland, up to 2015. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2006;37(1):15–25. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:37:1:15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janssen F, Kunst A. The choice among past trends as a basis for the prediction of future trends in old-age mortality. Popul Stud (Camb) 2007;61(3):315–326. doi: 10.1080/00324720701571632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilmoth JR. Demography of longevity: past, present, and future trends. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35(9–10):1111–1129. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(00)00194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janssen F, Kunst AE. ICD coding changes and discontinuities in trends in cause-specific mortality in six European countries, 1950–99. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(12):904–913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janssen F, Mackenbach JP, Kunst AE. Trends in old-age mortality in seven European countries, 1950–1999. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(2):203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferlay J, Autier P, Boniol M, Heanue M, Colombet M, Boyle P. Estimates of the cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2006. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(3):581–592. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Axon A. Helicobacter pylori: what do we still need to know? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(1):15–19. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000190752.48621.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Key TJ, Schatzkin A, Willett WC, Allen NE, Spencer EA, Travis RC. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of cancer. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(1A):187–200. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corley DA, Kubo A. Influence of site classification on cancer incidence rates: an analysis of gastric cardia carcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(18):1383–1387. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verdecchia A, Corazziari I, Gatta G, Lisi D, Faivre J, Forman D. Explaining gastric cancer survival differences among European countries. Int J Cancer. 2004;109(5):737–741. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E. Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(4):765–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amiri M, Kunst AE, Janssen F, Mackenbach JP. Trends in stomach cancer mortality in relation to living conditions in childhood. A study among cohorts born between 1860 and 1939 in seven European countries. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(18):3212–3218. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.La Vecchia C, Negri E, Levi F, Decarli A, Boyle P. Cancer mortality in Europe: effects of age, cohort of birth and period of death. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(1):118–141. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)00335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]