Abstract

There is an intense interest in differentiating embryonic stem cells to engineer biological pacemakers as an alternative to electronic pacemakers for patients with cardiac pacemaker function deficiency. Embryonic stem cell-derived cardiocytes (ESCs), however, often exhibit dysrhythmic excitations. Using Ca2+ imaging and patch-clamp techniques, we studied requirements for generation of spontaneous rhythmic action potentials (APs) in late-stage mouse ESCs. Sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) of ESCs generates spontaneous, rhythmic, wavelet-like Local Ca2+Releases (LCRs)(inhibited by ryanodine, tetracaine, or thapsigargin). L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) induces a global Ca2+ release (CICR), depleting the Ca2+ content SR which resets the phases of LCR oscillators. Following a delay, SR then generates a highly synchronized spontaneous Ca2+ release of multiple LCRs throughout the cell. The LCRs generate an inward Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) current (absent in Na+-free solution) that ignites the next AP. Interfering with SR Ca2+ cycling (ryanodine, caffeine, thapsigargin, cyclopiazonic acid, BAPTA-AM), NCX (Na+-free solution), or ICaL (nifedipine) results in dysrhythmic excitations or cessation of automaticity. Inhibition of cAMP/PKA signaling by a specific PKA inhibitor, PKI, decreases SR Ca2+ loading, substantially reducing both spontaneous LCRs (number, size, and amplitude) and rhythmic AP firing. In contrast, enhancing PKA signaling by cAMP increases the LCRs (number, size, duration) and converts irregularly beating ESCs to rhythmic “pacemaker-like” cells. SR Ca2+ loading and LCR activity could be also increased with a selective activation of SR Ca2+ pumping by a phospholamban antibody.

Conclusions

SR Ca2+ loading and spontaneous rhythmic LCRs are driven by inherent cAMP/PKA activity. ICaL synchronizes multiple LCR oscillators resulting in strong, partially synchronized diastolic Ca2+ release and NCX current. Rhythmic ESC automaticity can be achieved by boosting “coupling” factors, such as cAMP/PKA signaling, that enhance interactions between SR and sarcolemma.

Keywords: Embryonic stem cells, cardiac differentiation, local Calcium release, ion currents, biological pacemaker, cAMP, Protein Kinase A

Introduction

Sick Sinus Syndrome is a disorder and/or a loss of sinoatrial node pacemaker function that causes symptomatic bradycardia, which can lead to syncope and even sudden death. While electronic pacemakers remain a satisfactory therapy for Sick Sinus Syndrome, they have many limitations and shortcomings, including size (in pediatric patients), need for replacement, possibility of infection, absence of the autonomic rate modulation, etc. (review [1]). Cell therapy is thus emerging as an alternative promising approach for repair of the hearts pacemaker [2]. Since embryonic stem (ES) cells can differentiate into any cell type of the body, including highly differentiated heart cells [3], ES cell-derived cardiocytes (ESCs) have been recently extensively explored as a valuable substrate for creating the biological pacemakers [2].

Since in vitro-grown ESCs generate spontaneous action potentials (APs), and functionally integrate with ventricular myocytes in vitro [4] and with the host myocardium in vivo [5], they can indeed pace hearts after their implantation (as reported in guinea pigs [4] and pigs [6]) and can even overcome complete atrioventricular block in animal models [6]. While these results provide proof-of-concept evidence for these cells to function as biological pacemakers, some fundamental problems of this approach still remain unresolved.

Although spontaneously beating ESCs express major cardiac ion currents [3] and Ca2+ cycling proteins [7,8], they are not true adult pacemaker cells. Accordingly, a major problem to directly use the ESCs as biological pacemakers is that they beat irregularly and can cause arrhythmia [9,10]. Presently there is no effective means to improve rhythm characteristics of spontaneously beating ESCs.

Here we demonstrate that rhythmic automaticity of ESCs requires a complex dynamic integration of electrogenic sarcolemmal proteins (ion channels and transporters) and Ca2+ cycling proteins (Suppl.Fig.S1), i.e. similar to that recently discovered in adult sinoatrial node cells (SANC), the primary cardiac pacemaker cells (recent reviews [11,12] and numerical studies [13,14]). Specifically, diastolic local Ca2+ releases (LCRs) from sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) activate Na+/Ca2+ exchanger current, but L-type Ca2+ current during AP synchronizes the phases of LCR oscillators. Based on this mechanism, the present paper suggests a new principle of how to convert dysrhythmic beating of ESCs to rhythmic beating, a characteristic of a robust biological pacemaker, by boosting “coupling” factors, such as cAMP/PKA signaling, that drive spontaneous LCRs and enhance interactions between SR and sarcolemma.

Material and Methods

Mouse ES cells of line R1 were differentiated into cardiocytes using the “hanging drop” technique [3,15,16]. Single ESCs were isolated from in vitro-grown embryoid bodies by microdissection followed by collagenase treatment [15,16] (see Online Supplement for details). Since this study explored the integration of subcellular and sarcolemmal mechanisms of ESC automaticity, we used only late-stage differentiated ESCs (“7+ 9 to 20” days) that reportedly express both major ion channels (ICaL, If, INa, Ito, IK)[3], exchangers (NCX)[17] and Ca2+ cycling proteins (RyR2, SERCA2A, calsequestrin and phospholamban)[7,8](Suppl.Fig.S1). The fact that our cells generate high amplitude APs and Ca2+ transients in current clamp and spontaneous Ca2+ releases under voltage clamp (Results) indicates that these cells express major cardiac ion channels and Ca2+ cycling proteins. Details of electrophysiology, confocal Ca2+ imaging, data analysis, and chemical skinning of ESCs are described in Online Supplement. Pharmacological tools, used here to target key components of the integrative mechanism of ESC rhythmic automaticity, are also described in the Online Supplement (Suppl.Fig.S1). Chemicals were purchased from Sigma and Invitrogen. Doses of drugs are shown in the figures. Data are presented as mean±SEM. The statistical significance was evaluated by Student's t test. The signals were stable for the duration of our experiments (tested in time-matched vehicle controls, Suppl.Fig.S3,S4).

Results

Substantial spread in rhythmicity of AP firing by ESCs

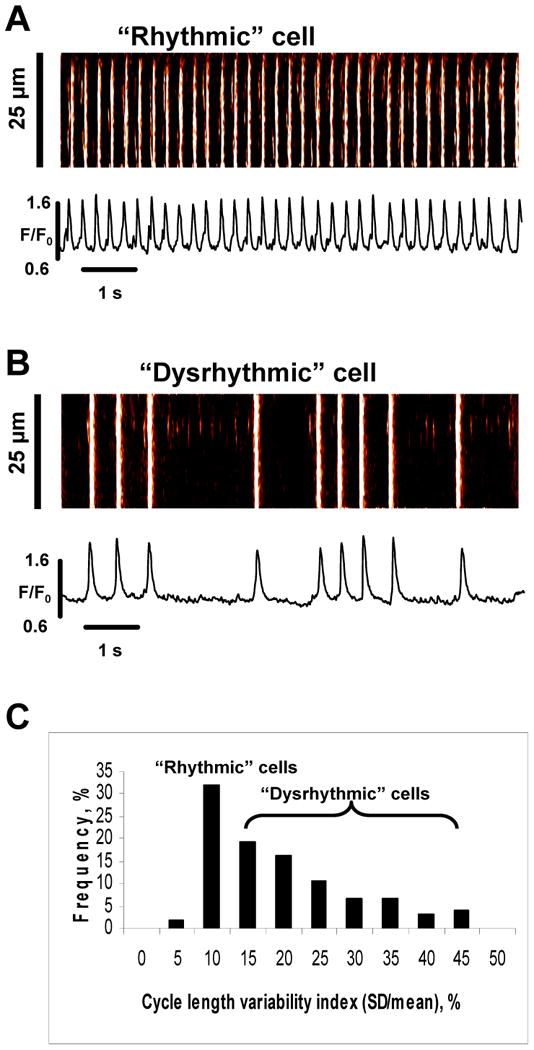

While many ESC exhibit spontaneous activity, the degree of regularity of spontaneous beating among different cells varies from rather regular (rhythmic) to very irregular (dysrhythmic) (Fig.1A,B). The rhythmicity of AP firing was assessed by calculating the cycle length (CL) variability index, also known as coefficient of variation [18], defined as 100%×CL standard deviation/CL mean. ESCs exhibit a broad range of CL variability index varying from about 5-12% (“rhythmic” cells) up to 45% (“dysrhythmic” cells) (Fig.1C). Correlation analysis of CL variability vs. basic electrophysiological parameters is presented in Suppl.Fig.S5.

Fig.1.

Broad variations of ESC intrinsic rhythm. A,B: Examples of Ca2+ transients in rhythmically and irregularly beating ESCs. C: Histogram of Cycle Length (CL) variability index (100%·SD/mean) measured in 21 ESCs.

ESCs possess Ca2+ clock similar to adult cardiac pacemaker cells

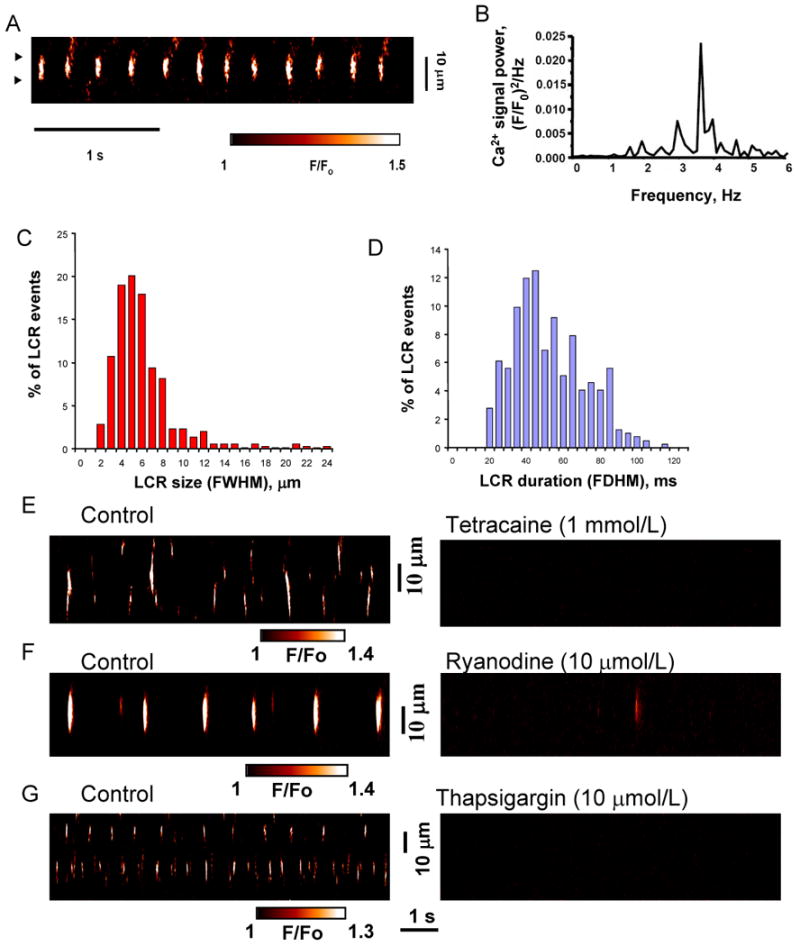

The major distinctive property of natural pacemakers, i.e. adult SANC, is its ability to spontaneously generate rhythmic wavelet-like LCRs (“Ca2+ clock”) independent of membrane function when activation of surface membrane ion channels is disabled in chemically skinned or voltage-clamped cells [12]. We experimentally tested whether ESCs, similar SANC, also possess the Ca2+ clock generating spontaneous LCRs under these conditions. Indeed, at a low bathing [Ca2+] of 150 nM and 35°C, chemically skinned ESCs produce wavelet-like LCRs (Fig.2A) that are rhythmic (see a power spectrum in Fig.2B) with a dominant frequency ranging from 1 to 6.5 Hz (3.9±0.5 Hz, n=10 cells). The LCRs range from 1.8 to 22 μm (5.58±0.12 μm, 747 LCRs, 17 cells) in size and from 20 to 110 ms in duration (49.2±0.9 ms) (Fig.2C,D). LCR size and duration are highly variable for any individual cell, with maximum and minimum differing at least in two times. The LCRs are likely produced by SR ryanodine receptors (RyRs) as they are inhibited by disabling either the RyRs (with ryanodine or tetracaine) or the SR Ca2+ pump (with thapsigargin) (Fig.2E-G).

Fig.2.

SR Ca2+ clock in “skinned” ES cell-derived cardiocytes. ESCs possess an intracellular, SR-based Ca2+ clock: spontaneous LCRs in saponin-“skinned” ESCs are rhythmic and linked to SR function (RyRs and SERCA). A: Confocal line-scan image of a representative “skinned” ESC. B, power spectrum of a continuous 27s-long recording of LCRs (for the average signal in a cell fragment between triangles in panel A). C,D: Histograms of LCR size and duration (747 LCRs, 17 cells). E-G: Confocal line-scan images of representative ESCs before (left) and after (right) superfusion with ryanodine, tetracaine, or thapsigargin (of 9, 9, and 5 cells tested, respectively). LCR spatial size was indexed as the full width at the half maximum amplitude (FWHM), and its duration characterized as the full duration at half maximum amplitude (FDHM).

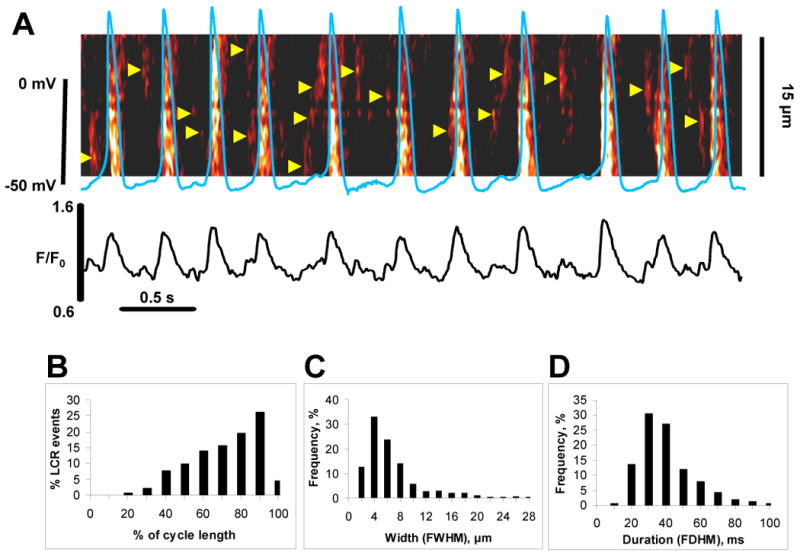

Also, similar to adult cardiac pacemaker cells [19,20], spontaneously beating ESCs generate LCRs (shown by triangles in Fig.3A) during the diastolic period, i.e. between APs or between global transients induced by the APs. The LCRs in intact cells range between 2 and 28 μm (5.94±0.24 μm, n=354) in size and 10 to 100 ms (35.98±0.84 ms, n=354) in duration (distributions in Fig.3C,D), i.e. similar to that in saponin-skinned ESCs (Fig.2C,D). The LCRs occur primarily in the second half of the cycle, with the occurrence rate increasing (i.e. becoming gradually more synchronous) before next excitation (distribution in Fig.3B for 423 LCRs measured in 21 cells).

Fig.3.

Local Ca2+ releases occur more frequently before excitations. LCRs emerge during diastole, with the rate of occurrence increasing with time, peaking just prior to the beginning of the next AP. A: Simultaneous recording of APs (blue line) and Ca2+ signals (confocal line-scan image) in an intact single spontaneously beating ESC. LCRs are shown with arrowheads. Also shown is the time course of the normalized fluorescence (F/F0) averaged along the scanline for the image above. B-D: Histograms of LCR phase, size, and duration (423 LCRs of 21 cells). The frequency of LCR occurrence within spontaneous cycles in panel B was measured by numerical comparison (in %) of each LCR period (a period of time from AP-induced Ca transient peak to the LCR peak) with the length of the spontaneous cycle, in which each LCR occurs.

LCRs generate spikes of inward NCX current that ignites action potentials

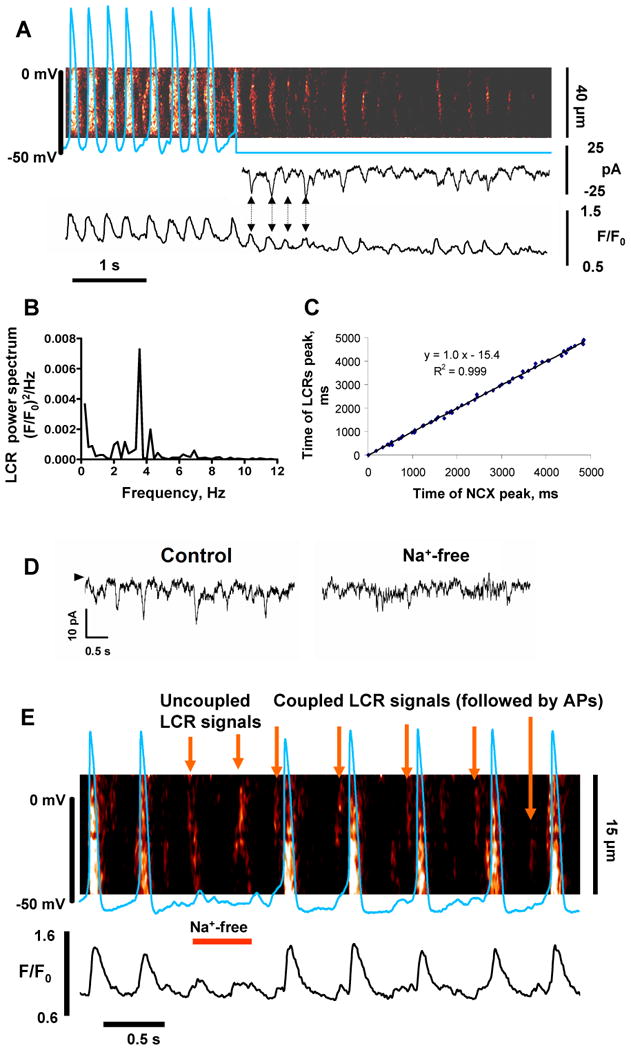

Next we tested the electrophysiological effects of LCRs. When activation of ion channels and APs are both disabled by voltage clamp at -50 mV, spontaneous LCRs occur for at least 5 s (see example in Fig.4A). Similar to the skinned cell configuration (Fig.2), the wavelet-like LCRs under voltage clamp are rhythmic with a dominant frequency of 2.3-5.2 Hz (3.95±0.19 Hz, n=4) (Fig.4B). Under voltage clamp, LCRs generate spikes of inward currents (Fig.4A, middle panel). The periodicity of the current spikes is identical to that of the LCR peaks (Fig.4C, and see also arrows connecting 4 first current peaks and 4 first Ca2+ signal peaks in Fig.4A). The almost coincident occurrence of LCRs and current spikes indicates a close cause-effect relationship between the two. LCRs likely cause the current spikes via NCX activation. The y-intercept in Fig.4C is the time delay between the NCX and LCR peaks. The negative value indicates that the LCR peak precedes the NCX peak by 15.4 ms. The delay is likely due to a propagation from the site of confocal measurement of the LCR to the NCX (membrane) location. The LCRs activate NCX current spikes because the high-amplitude current spikes (ranging 10 to 20 pA in control) disappear when NCX function is disabled in Na+-free medium (Na+ is substituted by Li+), and the residual small spikes (if any) become comparable to the current noise (within ∼5 pA) under these conditions (tested in 4 cells, see example in Fig.4D).

Fig.4.

Rhythmic, membrane-independent LCRs produce spikes of inward NCX current that ignite rhythmic APs. A: Simultaneous recordings of membrane potential or current and confocal line-scan image of Ca2+ release in a representative spontaneously beating ESC before and during voltage clamp to -50 mV. B: Power spectrum of LCRs during voltage clamp. C: Correlation plot between timing of LCRs and current spikes under voltage clamp. D: Inward currents in an ESC clamped at -50 mV (control) disappear after cell exposure to a rapid, brief Na+-free (Li+-containing) solution that disables NCX function. The arrowhead indicates the zero current level. E: Simultaneous recording of Ca2+ signals and APs in a spontaneously-active ESC which was exposed to a rapid and brief superfusion with a Na+-free solution (bar “Na+-free”) to inhibit NCX function. SR Ca2+ clock continues to generate LCRs, but the uncoupled LCR signals fail to ignite APs, until Na+ is restored and coupling re-established (“Coupled LCR signals”).

We performed “a first order estimate” for the total charge movement of one current spike and found that this charge can indeed substantially depolarize the cell membrane. The current spike shown in Fig 4D has a magnitude of about I=10 pA and lasts about t=100 ms, yielding a total charge movement of Q= I·t =10pA·0.1s=1pC. For a typical ESC with electrical membrane capacitance of C=50 pF, the respective voltage change ΔV is estimated to ΔV=Q/C=1pC/50pF=0.02V=20mV.

To test the importance of these LCR-activated currents for spontaneous beating, we shortly (for∼1 s) applied a Na+-free solution (“Na+-free spritz”) to spontaneously beating cells under zero-current perforated patch clamp and simultaneously imaged intracellular Ca2+ by confocal microscopy (Fig.4E). This Na+-free spritz resulted in acute, transient, partial inhibition of NCX (Na+ removal is incomplete during such short time). Under these conditions rhythmic LCRs continue (similarly to that in our voltage clamp experiments, Fig.4A) and produce partial depolarizations, insufficient to trigger APs.

We interpret this result to indicate that the LCR-initiated, NCX-mediated current spikes couple LCRs and the APs. Indeed, the excitation failure occurs because the cell is unable to depolarize to the threshold for firing of Ca2+ current and/or Na+ current (many ESCs express Na+ current [3]). Of note, since Na+ channels are highly permeable to Li+ (ionic permeability ratio PLi+/PNa+=0.93 [21], Na+ channel currents are expected to remain almost unchanged under these conditions. Importantly, as current spikes disappear in the Na+-free, Li+ solution, there was no remarkable change in the base current (i.e. the current offset vs. 0 level marked by arrow in Fig.4D), indicating that the net activity of all Na+-sensitive electrogenic mechanisms, other than NCX, is affected insignificantly by Li+ substitution for Na+.

Another possible effect of Na+ replacement might be related to If channel, which has a smaller conductance for Li+ vs. Na+ (although both minor vs. that for K+: PNa/PK = 0.11 and PLi/PK=0.03 [22]). To exclude the possibility that excitation failure in Fig.4E is linked to If, and also to test the importance of If in spontaneous beating of ESCs, we also examined effects of If inhibition. Specific blockade of If by 2 mM Cs2+ or by 7 μM UL-FS-49 (zatebradine) did not stop the spontaneous beating of ESCs, but moderately and reversibly reduced their beating rate (by ∼24 and 22%, n=16 and 15 cells, respectively, Suppl.Fig.S7,A-D). Our separate voltage clamp experiments insured that Cs+ and zatebradine indeed effectively suppressed If in ESCs (Suppl.Fig.S7,E,F).

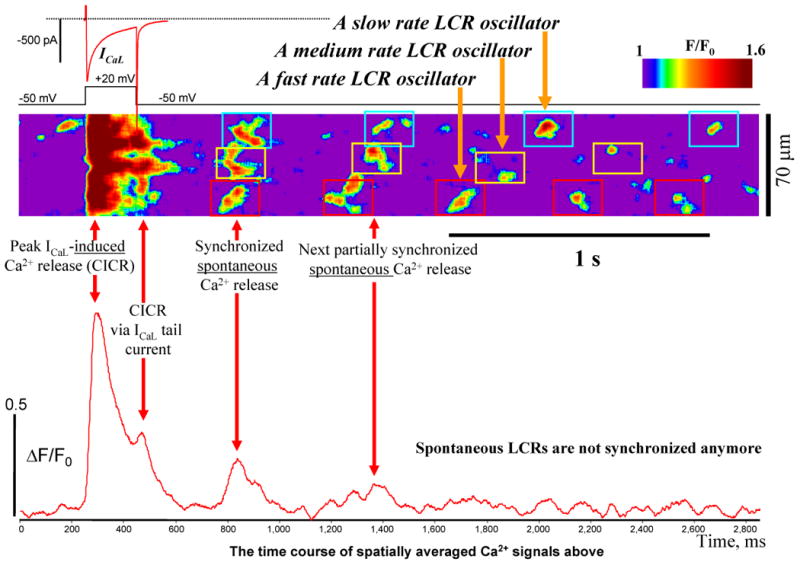

LCRs are synchronized by prior ICaL -triggered Ca2+ -induced Ca2+ release (CICR)

To record simultaneous activity of several local Ca2+ oscillators generating LCRs, the confocal line was extended over almost entire cell length (∼70 μm). It is important to note that this setting is different to that in our experiments in Fig.4, where the observation was limited to only one such Ca2+ oscillator within a span of 15-30 μm. Our voltage-clamp protocol included 5 preconditioning voltage pulses of 100 ms duration applied from -40 mV to 0 mV (1Hz rate). This pulse train was applied each time before a 200 ms testing pulse (Fig.5) in order to attain a standardized SR Ca2+ load (after the train) via the consecutive activation of ICaL (and Ca2+ influx).

Fig.5.

ICaL triggers CICR and thereby synchronizes phases of LCR oscillators. Shown is an example of simultaneous recordings of ICaL (voltage clamp) and Ca2+ dynamics (confocal line scan imaging over the entire cell length). ICaL was induced by a short voltage clamp pulse to 20 mV from a -50 mV holding potential. See text for details. To identify LCRs, our original confocal images were smoothed by spatiotemporal Gaussian filtering of 20×20 pixels (27.9ms × 4.76μm).

ICaL time course during the testing pulse had two peaks: the first peak activated by depolarization and the second peak (after 200 ms) in the form of the tail current (upper red trace in Fig.5). Thus, each testing voltage pulse activated CICR two times: first by the depolarization-induced ICaL peak and then, 200 ms later, by the ICaL current tail. (Of note, CICR via ICaL tail in cardiac cell under voltage clamp is well-known phenomenon and has been recently demonstrated also in ESCs [23]). Therefore about 300 ms after the ICaL tail-mediated CICR, the truly spontaneous releases (marked as “Synchronized spontaneous Ca2+ release” in the figure) emerge almost synchronously (i.e. largely overlapping in time), with the “fast” oscillator firing first, the “medium” one-next, and the “slow” one-the last (Fig.5). It is important to note that ICaL truly synchronizes spontaneous LCRs because LCRs before the testing pulse appeared to be random, i.e. not synchronized (Online suppl.Fig.S8). Such ICaL-synchronized LCRs' emergence results in a strong spatially averaged Ca2+ release (Fig.5, bottom trace). In the absence of a subsequent synchronizing event, i.e. ICaL-activated CICR, the second average spontaneous Ca2+ release has a larger spread in time and smaller amplitude (spontaneous LCRs emerge less synchronously). Since intrinsic rates of LCR oscillators are different (e.g. slow, medium, and fast in Fig.5), LCRs eventually become out of phase (i.e. desynchronized), with their spatial average becoming noisy. This pattern of ICaL-induced LCRs' synchronization was highly reproducible (tested in 8 cells), with the number (2 to 8) of partially synchronized LCR firings depending on the difference of the intrinsic rates of the local Ca2+ oscillators.

If ICaL is required for resetting and synchronization of LCRs (Fig.5), the rhythmic pacemaking activity of ESCs must be sensitive to the blockade of ICaL. Indeed, suppression of spontaneous beating produced in the presence of partial pharmacological blockade of ICaL by 200 nM of nifedipine was preceded by a temporal phase (of about 1 min duration) with substantial CL variability (tested in 6 cells, see an example in Suppl.Fig.S9).

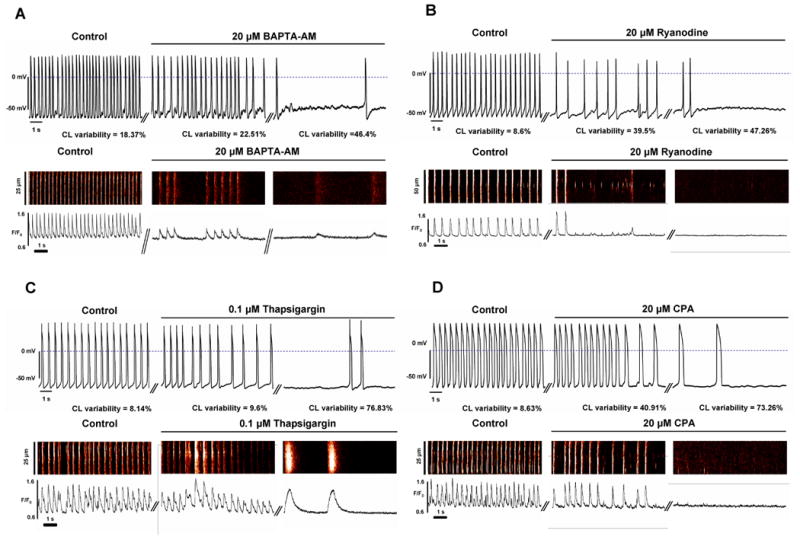

Ca2+ clock is driven by cAMP/PKA activity and is required for rhythmic AP firing

In order to demonstrate that generation of rhythmic APs requires SR-generated LCRs, we interfered to SR function and inhibit LCRs by buffering intracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA-AM, or by disabling RyR function with ryanodine, or by inhibiting SERCA with thapsigargin or cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) (n=5-8 cells for each intervention, see examples in Fig.6). Importantly, as LCRs decreased (in frequency and amplitude), spontaneous AP firing and Ca2+ transients became irregular with CL variability index significantly (p<0.05) increased from 12.7±2.62 to 60.3±13.02, from 11.78±1.66 to 57.4±9.26, and from 14.2±3.68 to 47.8±9.3, from 12.4±1.52 to 48.3±11.9% after application of the aforementioned drugs, respectively, culminating in cessation of automaticity or in extremely rare beating. A representative example of a detailed time-course for development of CPA-induced irregular beating, followed by a washout, is shown in Suppl.Fig.10. The time course of the ryanodine effect was, in fact, biphasic, i.e. the phase of rate decrease and irregular beating was preceded by a temporal initial increase in beating rate (see an example in Suppl.Fig.11). Such biphasic pattern is likely related to known characteristics of ryanodine to effect increased SR Ca2+ leakage immediately following its application, followed by diminished leakage or release due to luminal SR depletion. Caffeine, which decreases the threshold of RyR activation by cytosolic Ca2+, also induced irregular beating of ESCs culminating in cessation of automaticity (also likely due to luminal SR depletion) (Suppl.Fig.S12).

Fig.6.

Ca2+ clock is crucial for rhythmic AP firing: Strong Ca2+ buffering (A) or interfering with Ca2+ release (B) or Ca2+ pumping (C,D) result in irregular beating, often culminating in cessation of automaticity. Shown are recordings of spontaneous APs and confocal line scan images of Ca2+ signals of representative ESCs (different cells for APs and Ca2+) prior to and during exposure of the drugs (including an intermediate stage with irregular beating). Ca2+ images are shown along with their spatial average of the Ca2+ signal. The values for variability index of spontaneous APs are shown for each drug in control, in transition, at a steady state. The effects of ryanodine, thapsigargin and BAPTA-AM are not washable. A complete experiment with CPA effect, including washout, is provided in Online Suppl.Fig.S10. The effect of the drugs (except ryanodine) reached their steady-state within about 3 min. The effect of ryanodine was complex (biphasic, see Suppl. Fig.S11).

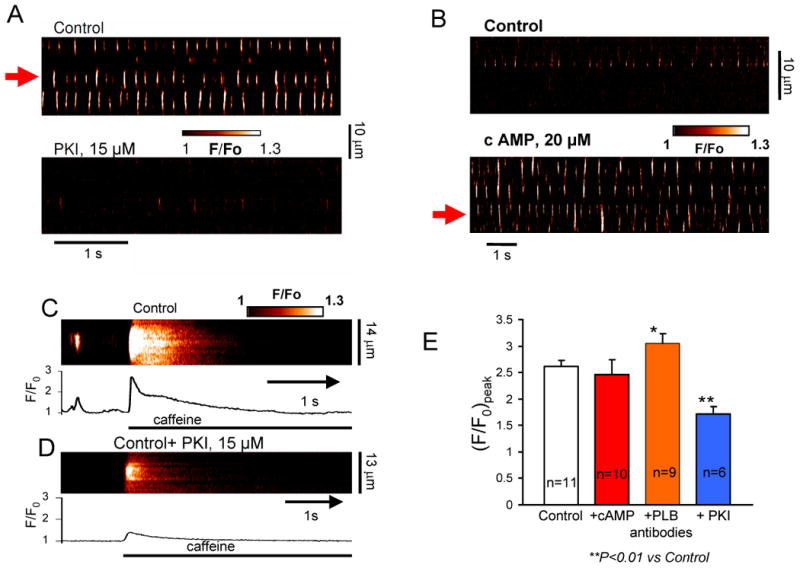

We tested whether basal cAMP-dependent PKA activation contributes to generation of spontaneous LCRs in ESCs. In saponin-skinned ESCs a specific peptide inhibitor of PKA (PKI) substantially decreases the number LCR oscillators (in 6 of 6 tested cells, see an example in Fig.7A and autocorrelation analysis in Suppl.Fig.S17A), with the residual LCRs (if any) becoming significantly less rhythmic, less frequent, and smaller in size and amplitude (for average data see Suppl.Fig.S13). (Of note, “less frequent” means that less number of events was observed within the 100 μm of scan line per unit of time.)

Fig.7.

Rhythmic local Ca2+ releases are driven by intrinsic cAMP/PKA activity that maintains SR Ca2+ loading. A, B: Confocal line-scan images of a representative skinned ESC before (top) and after (bottom) superfusion with a specific PKA inhibitor (PKI), or stimulation with cAMP. PKI decreases, but cAMP increases the number of local Ca2+ oscillators (demonstrated by autocorrelation analysis in Suppl. Fig. S17 for cell locations shown by red arrows). C,D: Representative examples of confocal line-scan images and their respective Ca2+ transients (spatial average) induced by rapid application of caffeine to skinned ESC in control and after incubation with PKI. E: Modulation of average amplitude (F/F0) peak of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients by PKI, cAMP, and PLB antibodies.

In contrast, application of cAMP to skinned cells (in 5 of 6 cells tested) resulted in the emergence of new local Ca2+ oscillators in many cell locations, which were “silent” before the cAMP boost (see an example in Fig.7B and autocorrelation analysis in Suppl.Fig.S17B). Two of 5 cAMP-responding cells, generated global, full-cell-length waves, i.e. their local Ca oscillators (including new oscillators) merge in one global oscillator. Analysis of LCR characteristics in 4 cells (of 6 tested cells) without global waves revealed that the LCRs become more rhythmic, more frequent, and larger in size (but not amplitude) (average data in Suppl.Fig.S14),

The mechanism of enhanced Ca2+ cycling by the SR resulting in LCRs in the basal state is likely linked to basal SR Ca2+ loading driven by the intrinsic cAMP/PKA-signaling, because the amplitudes of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients were significantly decreased (by ∼29%) when cells were pretreated with PKI inhibiting PKA signaling (Fig.7C,D,E).

We further explored the mechanism of LCR generation using an anti-phospholamban (PLB) antibody 2D12 [24]. The antibody prevents association of PLB with SR Ca2+ pump (SERCA), thereby selectively accelerating SR Ca2+ pumping, but (in contrast to cAMP) not affecting the release channel (RyR) properties. Thus applying the antibody simulates the case of selective SR Ca2+ pumping activation when PLB is almost fully phosphorylated. The PLB-antibody increased the LCR signal mass via larger (spatiotemporal) size and amplitude, but the LCR rate remained almost unchanged (Suppl.Figs S16). In half of cells tested (4 from 8), PLB-antibody produced long-lasting (persistent) LCRs (Suppl.Figs S15A,B), similar to those observed by Zima et al. [25] at low tetracaine concentrations in skinned ventricular myocytes (i.e. when SR Ca2+ pumping is relatively large vs. Ca2+ release). Caffeine transients were increased by PLB-antibody (e.g. Suppl.Figs S15C) but not by cAMP (average data in Fig.7E).

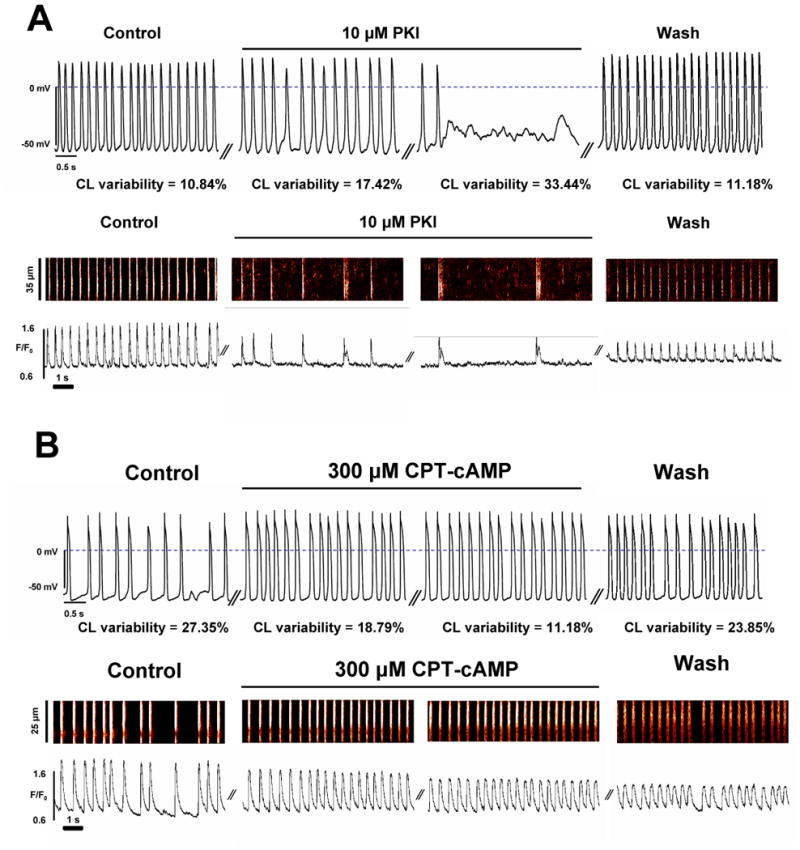

In spontaneously beating ESCs PKA inhibition by PKI (tested in 8 cells, Fig.8A) resulted in irregular APs (CL variability index significantly increased from 12.45±2.68 to 40.77±6.35%, p<0.05). In contrast, enhancing cAMP/PKA signaling by application of a membrane-permeable cAMP analogue (CPT-cAMP) converted irregularly beating ESCs to rhythmically beating cells (Fig.8B). In 5 cells with irregular beating, CPT-cAMP clearly increased the spontaneous rate and simulataneously significantly (P<0.05) improved CL variability index from 23.98±4.82% (dysrythmic AP firing) to 11.23±2.68% (rhythmic AP firing), i.e. converted all of these “dysrhythmic” cells into “rhythmic”, “pacemaker-like” cells.

Fig.8.

Intrinsic cAMP/PKA activity is required for ESCs to exhibit rhythmic automaticity (pacemaker-like cells). Typical examples of APs and Ca2+ releases recorded in spontaneously beating ESCs (different cells) before and during superfusion with PKI (panel A) or with CPT-cAMP (panel B). While inhibition of PKA activity by PKI deteriorates ESC automaticity, cell stimulation with cAMP converts dysrhythmic ESCs into pacemaker-like cells. The values for variability index of spontaneous APs are shown in control, in transition, at a steady state, and after washout. The drugs reached their steady-state effects within about 3 min.

Discussion

Prior studies considered an essentially sarcolemma-driven ESC automaticity, such as an interplay of Ca2+ and K+ currents [3], classical If mechanism [26], ICaT [27], and INa window current [28]. Other studies considered basically one-way effect of Ca2+ release on membrane function [16,29-32]. The present study, for the first time, explored the integrated function of SR and sarcolemma in late-stage ESCs to generate rhythmic APs. Multiple types of experimental evidence presented here indicate that the rhythmic automaticity of these in vitro-derived cells requires dynamically coupled function of Ca2+ cycling and membrane ion current activation (summarized in Suppl.Fig.1), i.e. similar to that recently discovered in adult cardiac pacemaker cells [11,12].

Specific mechanisms of rhythmic beating include biophysical (ICaL→synchronized LCRs→NCX → depolarization→ activation of ICaL+INa) and biochemical (intrinsic cAMP/PKA activation) coupled function of Ca2+ clock and membrane clock (i.e. the ensemble of voltage-gated ion channels). Pharmacological inhibition of LCRs or uncoupling of LCRs from membrane function results in dysrhythmic beating, culminating in cessation of automaticity or extremely rare (i.e. non-physiological) beating (Fig.6, Fig.4E, Suppl.Figs S9-S12). Rhythmic LCRs (Power spectrum in Fig.4B) interact with membrane clock via activation of NCX to ignite rhythmic APs in ESCs (Fig.4). This LCR→NCX coupling mechanism of rhythmic ESC automaticity is similar to that found in adult SANC [20] and embryonic cardiomyocytes [33,34].

ICaL, in turn, orchestrates the function of local Ca2+ oscillators. Simultaneous measurements of ICaL and LCRs in the present study directly show that the phases of the local Ca2+ oscillators are reset by CICR triggered by prior ICaL and the synchronized LCR emergence result in a strong average Ca2+ signal (Fig.5, “Synchronized spontaneous Ca2+ release”). The synchronized spontaneous Ca2+ releases occur with a delay of about 200-300 ms after peak ICaL and the Ca2+ transient it triggers (Fig.5). This delay has been referred to as LCR period in studies of SANC and the average LCR period determines the cycle length of spontaneous AP firing (reviews [11,35]). Without synchronization by ICaL, local Ca2+ oscillators eventually go out phase yielding a noisy spatial average (Fig.5 low panel, “LCRs are not synchronized”). The importance of such synchronization is evidenced by our finding that partial blockade of ICaL by nifedipine (Suppl. Fig.S9) results in dysrhythmic beating before the cell becomes inexcitable. On the contrary, only one LCR oscillator (even rhythmic one) may not be powerful enough (i.e. insufficient) to drive the rhythmic beating of the entire cell. Figure 1B shows an example when a rather rhythmic LCR oscillator is operating in a disrhythmic cell: the Ca2+ oscillator in the higher part of the scanning line makes 10 rhythmic cycles between beats 3 and 4, but these Ca2+ oscillations are uncoupled from the AP occurrences, so that the cell beats irregularly.

Prior detailed pharmacological studies of ICaL regulation in ESCs (using okadaic acid, IBMX, milrinone, etc.[36,37]) suggested that “ESCs are characterized by a high intrinsic adenylyl cyclase activity, which is conterbalanced by high intrinsic activity of phosphodiesterases and phosphatases” (cited from [36]). Although the specific levels of cAMP in ESCs have yet to be measured, the present study demonstrates that such inherent cAMP/PKA activity is critical for integrative rhythmic automaticity of ESCs, as it enhances not only basal ICaL [36,37], If [26], INa [38], and perhaps IK, but also basal Ca2+ cycling resulting in abundant spontaneous LCRs (Figs 7,8, Suppl.Fig.1). The critical importance of basal PKA activity for LCRs and cardiac pacemaker function has been also recently discovered in rabbit SANC [39]. A novel finding of the present study is that an intrinsic PKA-activation maintains Ca2+ SR loading (Fig.7C-E) and thereby likely causes the spontaneous Ca2+ releases (e.g. via activation by luminal Ca2+ [40]). Our result that caffeine transients are increased by PLB-antibody but not by cAMP (Fig.7E) can be interpreted to indicate that selective activation of SR Ca pumping indeed increases SR Ca2+ loading in ESCs but the cAMP-induced increase of basal LCR activity is not associated with an increase of SR Ca2+ load per se, but likely involves enhanced and matched pumping-release (i.e. PLB-SERCA-RyR) function. Indeed cAMP naturally enhances and couples both pumping and release because cAMP-dependent PKA phosphorylates both PLB and RyRs as we previously showed in sinoatrial node cells [39].

Interestingly, local Ca2+ oscillators of the mouse ESCs persist for at least for 4 seconds under voltage clamp at the maximum diastolic potential (Fig.4A). This means that the mouse ESCs likely have a mechanism to protect against NCX-mediated cell Ca2+ depletion. One possibility might be a link to store-operated Ca2+ influx, as recently discovered in mouse sinoatrial node [41].

One possibility to improve the rhythm of ESCs might be to decrease IK1, resulting in decreased hyperpolarization (smaller MDP in Fig.1D) that will likely facilitate coupling of Ca2+ clock and membrane clock, shifting ESCs in their relations towards a more rhythmic behavior (to the left, Fig.1D). The idea of targeting IK1 has been indeed previously suggested for engineering biological pacemakers from cardiomyocytes [42]. However, stabilization of the resting potential via developmentally increasing expression of IK1 [3,43] is likely not the single factor that interferes with rhythmic beating of ESCs. Our results with cAMP and PKI suggest that the reasons for irregular and rare beating of a majority of late-stage ESCs likely also include a decreased activity of Ca2+ cycling proteins (e.g. due to a developmental decrease in intracellular cAMP level [44] and/or an increased phospholamban expression [8]). Previous studies have demonstrated that the rate and rhythm of spontaneous beating of ESCs with RyR2 knock-out is substantially impaired (38 vs. 143 bpm, “KO” vs. wild type ESCs, respectively)[16]. Thus, the present results show (Figs7,8 and Suppl.Fig.S1) that the rhythm of ESCs can be improved by boosting Ca2+ cycling (i.e. LCRs) and coupling of electrophysiological and Ca2+ cycling mechanisms via targeting regulatory proteins, e.g. to maintain the high level of basal cAMP/PKA activity (as in adult pacemaker cells [39]). Indeed in the present study exposure to a membrane-permeable cAMP analogue was sufficient to convert “dysrhythmic” and/or rarely beating ESCs into “rhythmic” ESCs (Fig.8B). A critically important factor in rhythmic beating of ESCs, however, is not just increased cAMP level per se but likely cAMP-dependent PKA-mediated phosphorylation, because “rhythmic” cells became “dysrhythmic” or ceased beating when their PKA activity was inhibited (Fig.8A).

This new principle to enhance rhythmic beating of ESCs via boosting cAMP/PKA signaling that couples electrophysiological and Ca2+ cycling mechanisms, can be also relevant to human ESCs and, therefore, to prospective designs of biological pacemakers for patients. Indeed, high expression of major Ca2+ cycling proteins, such as L-type Ca2+ channels, NCX, SERCA2, IP3 receptors, and RyRs that generate both Ca2+ transients and wavelet-like, diastolic LCRs have been observed not only in mouse ESCs [3,7,8,16,17,31], but also in human ESCs [32,45]. Furthermore, local control of Ca2+ a releases by L-type Ca2+ channels in human ESCs [23] might be also important in synchronizing Ca2+ clocks (termed “local Ca2+ events” in these human cells[32]) to generate strong diastolic Ca2+ signals similarly to that shown in Figure 5.

In summary, the complex nature of cardiac pacemaker function and regulation has been the subject of debate and intensive experimental studies for long time. Evidence for the strongly coupled function of electrophysiology and intracellular Ca2+ cycling as a novel fundamental principle of normal cardiac impulse initiation and regulation in the sinoatrial node, the hearts natural pacemaker, is now emerging (recent reviews [11,12] and numerical studies [13,14]). The present study shows that this principle also underlies rhythmic automaticity of ESCs. Thus, genetic engineering of the ESC-based biological pacemakers to boost this cAMP/PKA-dependent integrative mechanism (Suppl.Fig.S1) would be of natural choice, i.e. evolution-selected and, therefore, highly robust and responsive.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging. We thank Larry Jones from Indiana University for providing anti-phospholamban antibody.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rosen MR, Brink PR, Cohen IS, Robinson RB. Genes, stem cells and biological pacemakers. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuldt AJ, Rosen MR, Gaudette GR, Cohen IS. Repairing damaged myocardium: evaluating cells used for cardiac regeneration. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2008;10:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s11936-008-0007-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maltsev VA, Wobus AM, Rohwedel J, Bader M, Hescheler J. Cardiomyocytes differentiated in vitro from embryonic stem cells developmentally express cardiac-specific genes and ionic currents. Circ Res. 1994;75:233–44. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xue T, Cho HC, Akar FG, Tsang SY, Jones SP, Marban E, et al. Functional integration of electrically active cardiac derivatives from genetically engineered human embryonic stem cells with quiescent recipient ventricular cardiomyocytes: insights into the development of cell-based pacemakers. Circulation. 2005;111:11–20. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151313.18547.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klug MG, Soonpaa MH, Koh GY, Field LJ. Genetically selected cardiomyocytes from differentiating embronic stem cells form stable intracardiac grafts. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:216–24. doi: 10.1172/JCI118769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kehat I, Khimovich L, Caspi O, Gepstein A, Shofti R, Arbel G, et al. Electromechanical integration of cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1282–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sauer H, Theben T, Hescheler J, Lindner M, Brandt MC, Wartenberg M. Characteristics of calcium sparks in cardiomyocytes derived from embryonic stem cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H411–21. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu JD, Li J, Tweedie D, Yu HM, Chen L, Wang R, et al. Crucial role of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in the developmental regulation of Ca2+ transients and contraction in cardiomyocytes derived from embryonic stem cells. Faseb J. 2006;20:181–3. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4501fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang YM, Hartzell C, Narlow M, Dudley SC., Jr Stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes demonstrate arrhythmic potential. Circulation. 2002;106:1294–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027585.05868.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macia E, Boyden PA. Stem cell therapy is proarrhythmic. Circulation. 2009;119:1814–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.779900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maltsev VA, Lakatta EG. Dynamic interactions of an intracellular Ca2+ clock and membrane ion channel clock underlie robust initiation and regulation of cardiac pacemaker function. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:274–84. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakatta EG, Maltsev VA, Vinogradova TM. A coupled SYSTEM of intracellular Ca2+ clocks and surface membrane voltage clocks controls the timekeeping mechanism of the heart's pacemaker. Circ Res. 2010;106:659–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maltsev VA, Lakatta EG. Synergism of coupled subsarcolemmal Ca2+ clocks and sarcolemmal voltage clocks confers robust and flexible pacemaker function in a novel pacemaker cell model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H594–H615. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01118.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maltsev VA, Lakatta EG. A novel quantitative explanation for autonomic modulation of cardiac pacemaker cell automaticity via a dynamic system of sarcolemmal and intracellular proteins. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H2010–H23. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00783.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maltsev VA, Rohwedel J, Hescheler J, Wobus AM. Embryonic stem cells differentiate in vitro into cardiomyocytes representing sinusnodal, atrial and ventricular cell types. Mech Dev. 1993;44:41–50. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90015-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang HT, Tweedie D, Wang S, Guia A, Vinogradova T, Bogdanov K, et al. The ryanodine receptor modulates the spontaneous beating rate of cardiomyocytes during development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9225–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142651999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otsu K, Kuruma A, Yanagida E, Shoji S, Inoue T, Hirayama Y, et al. Na+/K+ ATPase and its functional coupling with Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in mouse embryonic stem cells during differentiation into cardiomyocytes. Cell Calcium. 2005;37:137–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilders R, Jongsma HJ. Beating irregularity of single pacemaker cells isolated from the rabbit sinoatrial node. Biophys J. 1993;65:2601–13. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81289-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huser J, Blatter LA, Lipsius SL. Intracellular Ca2+ release contributes to automaticity in cat atrial pacemaker cells. J Physiol. 2000;524(Pt 2):415–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogdanov KY, Vinogradova TM, Lakatta EG. Sinoatrial nodal cell ryanodine receptor and Na+-Ca2+ exchanger: molecular partners in pacemaker regulation. Circ Res. 2001;88:1254–8. doi: 10.1161/hh1201.092095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 2. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xue T, Li RA. An external determinant in the S5-P linker of the pacemaker (HCN) channel identified by sulfhydryl modification. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46233–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu WZ, Santana LF, Laflamme MA. Local control of excitation-contraction coupling in human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z, Akin BL, Jones LR. Mechanism of reversal of phospholamban inhibition of the cardiac Ca2+-ATPase by protein kinase A and by anti-phospholamban monoclonal antibody 2D12. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20968–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703516200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zima AV, Picht E, Bers DM, Blatter LA. Termination of cardiac Ca2+ sparks: role of intra-SR [Ca2+], release flux, and intra-SR Ca2+ diffusion. Circ Res. 2008;103:e105–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.183236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abi-Gerges N, Ji GJ, Lu ZJ, Fischmeister R, Hescheler J, Fleischmann BK. Functional expression and regulation of the hyperpolarization activated non-selective cation current in embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 2000;523(Pt 2):377–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yanagi K, Takano M, Narazaki G, Uosaki H, Hoshino T, Ishii T, et al. Hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels and T-type calcium channels confer automaticity of embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2712–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satin J, Kehat I, Caspi O, Huber I, Arbel G, Itzhaki I, et al. Mechanism of spontaneous excitability in human embryonic stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 2004;559:479–96. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Fleischmann BK, Liu Q, Sauer H, Gryshchenko O, Ji GJ, et al. Intracellular Ca2+ oscillations drive spontaneous contractions in cardiomyocytes during early development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8259–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mery A, Aimond F, Menard C, Mikoshiba K, Michalak M, Puceat M. Initiation of embryonic cardiac pacemaker activity by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent calcium signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2414–23. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kapur N, Banach K. Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated spontaneous activity in mouse embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 2007;581:1113–27. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.125955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Satin J, Itzhaki I, Rapoport S, Schroder EA, Izu L, Arbel G, et al. Calcium Handling in Human Embryonic Stem Cell Derived Cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells. 2008 doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rapila R, Korhonen T, Tavi P. Excitation-contraction coupling of the mouse embryonic cardiomyocyte. J Gen Physiol. 2008;132:397–405. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200809960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sasse P, Zhang J, Cleemann L, Morad M, Hescheler J, Fleischmann BK. Intracellular Ca2+ oscillations, a potential pacemaking mechanism in early embryonic heart cells. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:133–44. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lakatta EG, Vinogradova TM, Maltsev VA. The missing link in the mystery of normal automaticity of cardiac pacemaker cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1123:41–57. doi: 10.1196/annals.1420.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maltsev VA, Ji GJ, Wobus AM, Fleischmann BK, Hescheler J. Establishment of β-adrenergic modulation of L-type Ca2+ current in the early stages of cardiomyocyte development. Circ Res. 1999;84:136–45. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ji GJ, Fleischmann BK, Bloch W, Feelisch M, Andressen C, Addicks K, et al. Regulation of the L-type Ca2+ channel during cardiomyogenesis: switch from NO to adenylyl cyclase-mediated inhibition. Faseb J. 1999;13:313–24. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsuda JJ, Lee H, Shibata EF. Enhancement of rabbit cardiac sodium channels by beta-adrenergic stimulation. Circ Res. 1992;70:199–207. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vinogradova TM, Lyashkov AE, Zhu W, Ruknudin AM, Sirenko S, Yang D, et al. High basal protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation drives rhythmic internal Ca2+ store oscillations and spontaneous beating of cardiac pacemaker cells. Circ Res. 2006;98:505–14. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000204575.94040.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gyorke S, Gyorke I, Lukyanenko V, Terentyev D, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Wiesner TF. Regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release by luminal calcium in cardiac muscle. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d1454–63. doi: 10.2741/A852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ju YK, Chu Y, Chaulet H, Lai D, Gervasio OL, Graham RM, et al. Store-operated Ca2+ influx and expression of TRPC genes in mouse sinoatrial node. Circ Res. 2007;100:1605–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.152181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miake J, Marban E, Nuss HB. Biological pacemaker created by gene transfer. Nature. 2002;419:132–3. doi: 10.1038/419132b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sartiani L, Bettiol E, Stillitano F, Mugelli A, Cerbai E, Jaconi ME. Developmental changes in cardiomyocytes differentiated from human embryonic stem cells: a molecular and electrophysiological approach. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1136–44. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang ZF, Sun Y, Li CZ, Wang HW, Wang XJ, Zheng YQ, et al. Reduced sinoatrial cAMP content plays a role in postnatal heart rate slowing in the rabbit. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33:757–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dolnikov K, Shilkrut M, Zeevi-Levin N, Gerecht-Nir S, Amit M, Danon A, et al. Functional properties of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: intracellular Ca2+ handling and the role of sarcoplasmic reticulum in the contraction. Stem Cells. 2006;24:236–45. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.